Why Ecological Modeling is a Foundational Skill for Biomedical Researchers

This guide demystifies ecological modeling for biomedical professionals, illustrating its power as a 'virtual laboratory' for drug discovery and environmental health research.

Why Ecological Modeling is a Foundational Skill for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This guide demystifies ecological modeling for biomedical professionals, illustrating its power as a 'virtual laboratory' for drug discovery and environmental health research. It provides a clear pathway from foundational concepts and niche modeling techniques to rigorous model calibration and validation. By adopting these methodologies, researchers can enhance the predictive power and reproducibility of their work, leading to more robust conclusions in areas like toxicology, disease dynamics, and ecosystem impact assessments.

The Virtual Laboratory: Foundational Concepts of Ecological Modeling

Defining Ecological Models and Their Role as a Scientific Tool

Ecological models are quantitative frameworks used to analyze complex and dynamic ecosystems. They serve as indispensable tools for understanding the interplay between organisms and their environment, allowing scientists to simulate ecological processes, predict changes, and inform sustainable resource management [1]. The core premise of ecological modeling is to translate our understanding of ecological principles into mathematical formulations and computational algorithms. This translation enables researchers and policymakers to move beyond qualitative descriptions and toward testable, quantitative predictions about ecological systems. For beginners in research, grasping the fundamentals of ecological modeling is crucial, as these models provide a structured approach to tackling some of the most pressing environmental challenges, including climate change, biodiversity loss, and the management of natural resources.

The utility of ecological models extends across numerous fields, from conservation biology and epidemiology to public health and drug development. In the context of a broader thesis, it is essential to recognize that ecological modeling represents a convergence of ecology, mathematics, and computer science. This interdisciplinary nature empowers researchers to address scientific and societal questions with rigor and transparency. Modern ecological modeling leverages both process-based models, which are built on established ecological theories, and data-driven models, which utilize advanced machine learning techniques to uncover patterns from complex datasets [1]. This guide provides an in-depth technical foundation for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals beginning their journey into this critical scientific toolkit.

A Framework of Model Types

Ecological models can be broadly categorized based on their underlying structure and approach to representing ecological systems. Understanding this classification is the first step in selecting the appropriate tool for a specific research question. The two primary categories are process-based models and data-driven models, each with distinct philosophies and applications.

Process-based models, also known as mechanistic models, are grounded in ecological theory. They attempt to represent the fundamental biological and physical processes that govern a system. Conversely, data-driven models are more empirical, using algorithms to learn the relationships between system components directly from observational or experimental data [1]. The choice between these approaches depends on the research objectives, the availability of data, and the level of mechanistic understanding required.

Process-Based Ecological Models

Process-based models are derived from first principles and are designed to simulate the causal mechanisms driving ecological phenomena. The following table summarizes some fundamental types of process-based models.

Table 1: Key Types of Process-Based Ecological Models

| Model Type | Key Characteristics | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Biogeochemical Models [1] | Focus on the cycling of nutrients and elements (e.g., carbon, nitrogen) through ecosystems. | Forecasting ecosystem responses to climate change; assessing carbon sequestration. |

| Dynamic Population Models [1] | Describe changes in population size and structure over time using differential or difference equations. | Managing wildlife harvests; predicting the spread of infectious diseases. |

| Ecotoxicological Models [1] | Simulate the fate and effects of toxic substances in the environment and on biota. | Environmental risk assessment for chemicals; setting safety standards for pollutants. |

| Spatially Explicit Models [1] | Incorporate geographic space, often using raster maps or individual-based movement. | Conservation planning for protected areas; predicting species invasions. |

| Structurally Dynamic Models (SDMs) [1] | Unique in that model parameters (e.g., feeding rates) can change over time to reflect adaptation. | Studying ecosystem response to long-term stressors like gradual climate shifts. |

Data-Driven Ecological Models

With the advent of large datasets and increased computational power, data-driven models have become increasingly prominent in ecology. These models are particularly useful when the underlying processes are poorly understood or too complex to be easily described by theoretical equations.

Table 2: Key Types of Data-Driven Ecological Models

| Model Type | Key Characteristics | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) [1] | Network of interconnected nodes that learns non-linear relationships between input and output data. | Predicting species occurrence based on environmental variables; water quality forecasting. |

| Decision Tree Models [1] | A predictive model that maps observations to conclusions through a tree-like structure of decisions. | Habitat classification; identifying key environmental drivers of species distribution. |

| Ensemble Models [1] | Combines multiple models (e.g., multiple algorithms) to improve predictive performance and robustness. | Ecological niche modeling; species distribution forecasting under climate change scenarios. |

| Support Vector Machines (SVM) [1] | A classifier that finds the optimal hyperplane to separate different classes in a high-dimensional space. | Classification of ecosystem types; analysis of remote sensing imagery. |

| Deep Learning [1] | Uses neural networks with many layers to learn from complex, high-dimensional data like images or sounds. | Automated identification of species from camera trap images or audio recordings. |

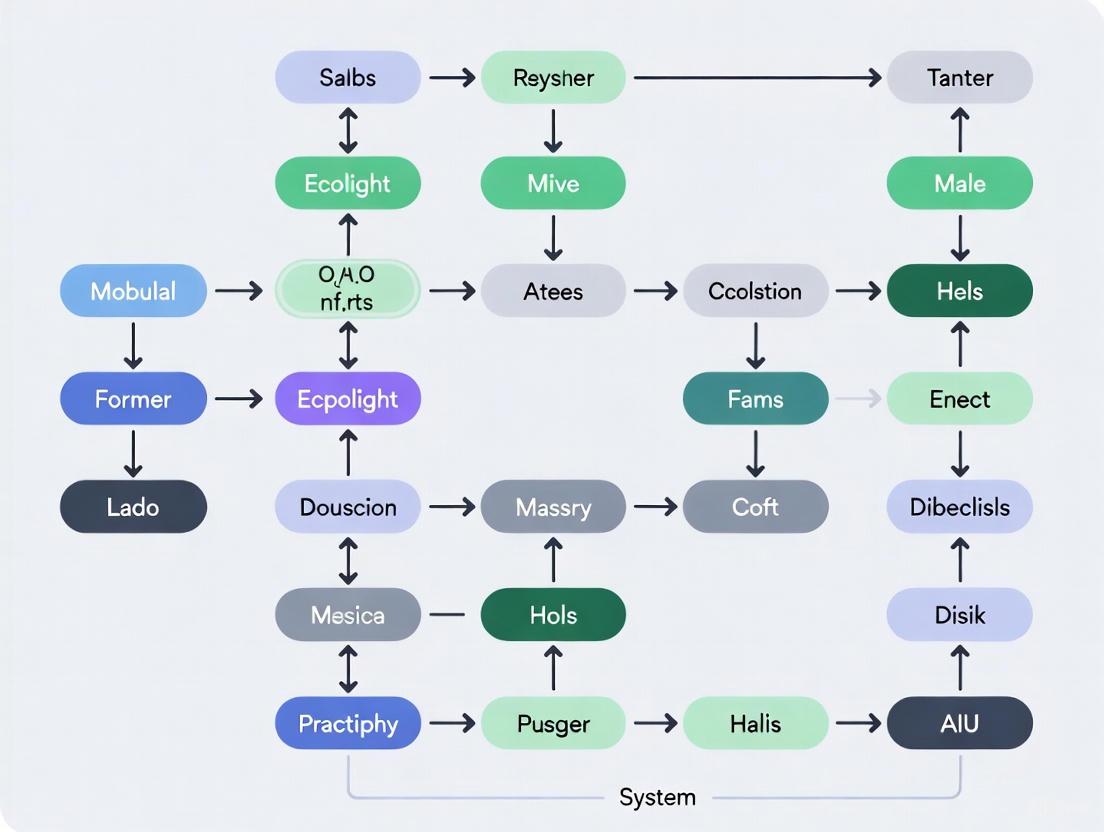

This classification is visualized in the following workflow, which outlines the logical relationship between the core modeling philosophies and their specific implementations:

Standardized Protocols for Model Evaluation

A critical aspect of ecological modeling, especially for beginner researchers, is the rigorous evaluation of model performance. The OPE (Objectives, Patterns, Evaluation) protocol provides a standardized framework to ensure transparency and thoroughness in this process [2]. This 25-question protocol guides scientists through the essential steps of documenting how a model is evaluated, which in turn helps other scientists, managers, and stakeholders appraise the model's suitability for addressing specific questions.

The OPE Protocol Framework

The OPE protocol is organized into three major parts, each designed to document a critical component of the model evaluation process:

- Objectives: This initial phase requires a clear statement of the modeling application's purpose and the specific scientific or societal question it aims to answer. Defining the objective upfront ensures that the subsequent evaluation is aligned with the model's intended use.

- Patterns: Here, the key ecological patterns that the model is expected to reproduce are identified and described. These patterns could relate to spatial distributions, temporal dynamics, species abundances, or ecosystem fluxes. Specifying these patterns makes the evaluation targeted and ecologically relevant.

- Evaluation: This is the core of the protocol, where the methodologies for assessing the model's performance against the identified patterns are detailed. It includes the choice of performance metrics (e.g., R², AUC, RMSE), data used for validation, and the results of the skill assessment [2].

Applying the OPE protocol early in the modeling process, not just as a reporting tool, encourages deeper thinking about model evaluation and helps prevent common pitfalls such as overfitting or evaluating a model against irrelevant criteria. This structured approach is vital for building credibility and ensuring that ecological models provide reliable insights for decision-making.

Practical Workflow and Reagent Solutions

For researchers embarking on an ecological modeling project, particularly in fields like ecological niche modeling (ENM), a theory-driven workflow is essential for robust outcomes. A practical framework emphasizes differentiating between a species' fundamental niche (the full range of conditions it can physiologically tolerate) and its realized niche (the range it actually occupies due to biotic interactions and dispersal limitations) [3]. The choice of algorithm is critical, as some, like Generalized Linear Models (GLMs), may more effectively reconstruct the fundamental niche, while others, like certain machine learning algorithms, can overfit to the data of the realized niche and perform poorly in novel conditions [3].

Theory-Driven Workflow for Ecological Niche Modeling

The following diagram illustrates a conceptual framework that guides modelers from defining research goals to generating actionable predictions, integrating ecological theory at every stage to improve model interpretation and reliability.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Executing an ecological modeling study requires a suite of computational and data "reagents." The following table details essential tools and their functions, forming a core toolkit for researchers.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Ecological Modeling

| Tool Category / 'Reagent' | Function | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Species Distribution Data | The primary occurrence data used to calibrate and validate models. | Museum records (e.g., GBIF), systematic surveys, telemetry data. Quality control is critical. |

| Environmental Covariate Data | GIS raster layers representing environmental factors that constrain species distributions. | WorldClim (climate), SoilGrids (soil properties), MODIS (remote sensing). |

| Modeling Software Platform | The computational environment used to implement modeling algorithms. | R (with packages like dismo [3]), Python (with scikit-learn), BIOMOD [3]. |

| Algorithm Set | The specific mathematical procedure used to build the predictive model. | GLMs, MaxEnt, Random Forests, Artificial Neural Networks [1] [3]. |

| Performance Metrics | Quantitative measures used to evaluate model accuracy and predictive skill. | AUC, True Skill Statistic (TSS), Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) [2]. |

The Indispensable Role of Ecological Modeling

Ecological models have evolved into a sophisticated scientific toolkit that is indispensable for addressing complex, multi-scale environmental problems. For beginner researchers, understanding the landscape of model types—from traditional process-based models to modern data-driven machine learning approaches—provides a foundation for selecting the right tool for the task. Furthermore, adhering to standardized evaluation protocols like the OPE framework ensures scientific rigor and transparency [2].

The true power of ecological modeling lies in its ability to integrate theory and data to forecast ecological phenomena. This predictive capacity is directly applicable to critical societal issues, from mapping the potential spread of invasive species and pathogens [3] to designing protected areas for biodiversity conservation [3]. By providing a quantitative basis for decision-making, ecological models bridge the gap between ecological theory and practical environmental management, solidifying their role as a fundamental scientific tool in the pursuit of sustainable development [1].

Ecological modeling serves as a critical framework for understanding and predicting the complex interactions within and between Earth's major systems. For researchers entering this field, grasping the core components—the atmosphere, oceans, and biological populations—is foundational. These components form the essential pillars upon which virtually all ecological and environmental models are built. The atmosphere and oceans function as dynamic fluid systems that regulate global climate and biogeochemical cycles, while biological populations represent the living entities that respond to and influence these physical systems. Mastering the quantitative representation of these components enables beginners to construct meaningful models that can inform conservation strategies, resource management, and policy decisions aimed at achieving sustainability goals.

This guide provides a technical introduction to the data, methods, and protocols for modeling these core components, with a focus on practical application for early-career researchers and scientists transitioning into ecological fields.

Core Component 1: The Atmosphere

The atmosphere is a critical component in ecological modeling, directly influencing climate patterns, biogeochemical cycles, and surface energy budgets. For researchers, understanding and quantifying atmospheric drivers is essential for projecting ecosystem responses.

Key Quantitative Data and Variables

Atmospheric models rely on specific physical and chemical variables. The table below summarizes the core quantitative data used in atmospheric modeling for ecological applications.

Table 1: Core Atmospheric Variables for Ecological Models

| Variable Category | Specific Variable | Measurement Units | Ecological Significance | Common Data Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greenhouse Gases | CO₂ Concentration | ppm (parts per million) | Primary driver of climate change via radiative forcing; impacts plant photosynthesis | NOAA Global Monitoring Laboratory [4] |

| CO₂ Annual Increase | ppm/year | Tracks acceleration of anthropogenic climate forcing | Lan et al. 2025 [4] | |

| Climate Forcings | Air Temperature | °C | Directly affects species metabolic rates, phenology, and survival | NOAA NODD Program [5] |

| Vapor Pressure Deficit (VPD) | kPa | Regulates plant transpiration and water stress; influences wildfire risk | Flux Tower Networks [6] |

Experimental Protocols for Atmospheric Data Assimilation

Protocol: Integration of Atmospheric Data into Terrestrial Productivity Models

The FLAML-Light Use Efficiency (LUE) model development provides a robust methodology for connecting atmospheric data to ecosystem processes [6].

Data Collection and Inputs:

- Meteorological Data: Obtain time-series data for surface air temperature, solar radiation, and Vapor Pressure Deficit (VPD).

- Satellite Data: Acquire satellite-derived indices, such as the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) or Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI), to represent light absorption by vegetation.

- In-Situ Flux Data: Use eddy covariance flux tower observations of Gross Primary Productivity (GPP) for model training and validation.

Model Optimization:

- Implement a lightweight Automated Machine Learning (AutoML) framework, such as FLAML, to automatically optimize the model's parameters.

- The AutoML system performs hyperparameter tuning to identify the most efficient model configuration that minimizes the difference between predicted and observed GPP.

Model Application and Validation:

- Apply the optimized FLAML-LUE model to predict GPP dynamics across different ecosystems (e.g., forests, grasslands, croplands).

- Validate model performance against held-out flux tower data and widely used satellite-derived products (e.g., MODIS GPP). The model has shown particularly strong predictive accuracy in mixed and coniferous forests [6].

Core Component 2: The Oceans

The ocean is a major regulator of the Earth's climate, absorbing both carbon dioxide and excess heat. Modeling its physical and biogeochemical properties is therefore indispensable for global change research.

Key Quantitative Data and Variables

Ocean models synthesize data from diverse platforms to represent complex marine processes. The following table outlines key variables and the platforms that measure them.

Table 2: Core Oceanic Variables and Observing Platforms for Ecological Models

| Variable Category | Specific Variable | Measurement Units | Platforms for Data Collection | Ecological & Climate Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon Cycle | CO₂ Fugacity (fCO₂) | μatm | Research vessels, Ships of Opportunity, Moorings, Drifting Buoys | Quantifies the ocean carbon sink; used to calculate air-sea CO₂ fluxes [4] |

| Ocean Carbon Sink | PgC (Peta-grams of Carbon) | Synthesized from surface fCO₂ and atmospheric data | Absorbed ~200 PgC since 1750, mitigating atmospheric CO₂ rise [4] | |

| Physical Properties | Sea Surface Temperature (SST) | °C | Satellites, Argo Floats, Moorings | Indicator of marine heatwaves; affects species distributions and fisheries [7] |

| Bottom Temperature | °C | Trawl Surveys, Moorings, Regional Ocean Models (e.g., NOAA MOM6) | Critical for predicting habitat for benthic and demersal species (e.g., snow crab) [7] | |

| Biogeochemistry | Oxygen Concentration | mg/L | Profiling Floats, Moorings, Gliders | Hypoxia stressor for marine life; declining with warming [7] |

| pH (Acidification) | pH units | Ships, Moorings, Sensors on Buoys | Calculated from carbonate system; impacts calcifying organisms and ecosystems [4] |

Experimental Protocols for Ocean Carbon Database Synthesis

Protocol: Construction and Curation of the Surface Ocean CO₂ Atlas (SOCAT)

SOCAT provides a globally synthesized, quality-controlled database of surface ocean CO₂ measurements, which is a primary reference for quantifying the ocean carbon sink [4].

Data Submission and Gathering:

- Collect data from approximately 495 individual sources, including organized oceanographic campaigns, ships of opportunity, and sensors on moorings or drifting platforms.

- Compile metadata for each measurement, including precise location, date, time, depth, and instrumental method.

Rigorous Quality Control (QC):

- Perform initial QC by data submitter.

- Conduct secondary QC by regional experts following a standardized QC cookbook [4]. This involves:

- Checking for internal consistency and outliers.

- Comparing data from different sources in the same region.

- Assigning a definitive Quality Flag to each data point.

Data Synthesis and Product Generation:

- Merge all qualified data into a unified, publicly accessible database.

- Generate gridded products at different spatial and temporal resolutions for easier use in models and trend analyses.

- Develop and provide open-source codes (e.g., in Matlab) for reading data files and gridded products.

The entire workflow is community-driven, relying on the voluntary efforts of an international consortium of researchers to ensure data quality and accessibility [4].

Figure 1: SOCAT data synthesis workflow for ocean carbon data.

Core Component 3: Biological Populations

Modeling biological populations moves beyond abiotic factors to capture the dynamics of life itself, including diversity, distribution, genetic adaptation, and responses to environmental change.

Key Quantitative Data and Variables

Modern population modeling integrates genetic, species, and ecosystem-level data to forecast biodiversity change.

Table 3: Core Data Types for Modeling Biological Populations

| Data Type | Specific Metric | Unit/Description | Application in Forecasting | Emerging Technologies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Diversity | Genetic EBVs (Essential Biodiversity Variables) | Unitless indices (e.g., heterozygosity, allelic richness) | Tracks capacity for adaptation; predicts extinction debt and resilience [8] | High-throughput genome sequencing, Macrogenetics [8] |

| Species Distribution | Species Abundance & Richness | Counts, Density (individuals/area) | Models population viability and range shifts under climate/land-use change | Species Distribution Models (SDMs), AI/ML [9] |

| Community Composition | Functional Traits | e.g., body size, dispersal ability | Predicts ecosystem function and stability under global change | Remote Sensing (Hyperspectral), eDNA [10] |

| Human-Environment Interaction | Vessel Tracking Data | AIS (Automatic Identification System) pings | Quantifies fishing effort, compliance with MPAs, and responses to policy [11] | Satellite AIS, AI-based pattern recognition [11] |

Experimental Protocols for Forecasting Genetic Diversity

Protocol: Integrating Genetic Diversity into Biodiversity Forecasts using Macrogenetics

This protocol outlines a method to project genetic diversity loss under future climate and land-use change scenarios, addressing a critical gap in traditional biodiversity forecasts [8].

Data Compilation:

- Gather genetic marker data (e.g., SNPs, microsatellites) from public repositories for a wide range of species and populations.

- Compile spatial layers of historical and contemporary anthropogenic drivers (e.g., human population density, land-use change) and climate variables.

Model Development and Forecasting:

- Use macrogenetic approaches to establish a statistical relationship between the current spatial patterns of genetic diversity (e.g., heterozygosity) and the environmental drivers.

- Apply this established relationship to future scenarios of climate and land-use (e.g., IPCC's SSP-RCP scenarios) to project future spatial patterns of genetic diversity loss or change.

Model Validation and Complementary Approaches:

- Theoretical Modeling: Use the Mutations-Area Relationship (MAR), analogous to the species-area relationship, to provide independent estimates of genetic diversity loss expected from habitat reduction [8].

- Individual-Based Models (IBMs): For high-priority species, develop fine-scale, process-based simulations to model how demographic and evolutionary processes shape genetic diversity over time under projected environmental changes [8].

Figure 2: Forecasting genetic diversity using macrogenetics and modeling.

For researchers beginning in ecological modeling, familiarity with key datasets, platforms, and software is crucial. The following table details essential "research reagents" for working with the core components.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Ecological Modelers

| Tool Name | Type | Core Component | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| SOCAT Database | Data Product | Oceans | Provides quality-controlled, global surface ocean CO₂ measurements (fCO₂) essential for quantifying the ocean carbon sink and acidification studies [4]. |

| Global Fishing Watch AIS Data | Data Product | Biological Populations | Provides vessel movement data derived from Automatic Identification System (AIS) signals to analyze fishing effort, vessel behavior, and marine policy efficacy [11]. |

| FLAML (AutoML) | Software Library | Atmosphere / General | An open-source Python library for Automated Machine Learning that automates model selection and hyperparameter tuning, useful for optimizing ecological models like GPP prediction [6]. |

| Argo Float Data | Data Platform | Oceans | A global array of autonomous profiling floats that measure temperature, salinity, and other biogeochemical parameters of the upper ocean, providing critical in-situ data for model validation. |

| Genetic EBVs | Conceptual Framework / Metric | Biological Populations | Standardized, scalable genetic metrics (e.g., genetic diversity, differentiation) proposed by GEO BON to track changes in intraspecific diversity over time [8]. |

| MODIS / Satellite-derived GPP | Data Product | Atmosphere | Widely used remote sensing products that provide estimates of Gross Primary Productivity across the globe, serving as a benchmark for model development and validation [6]. |

| Noah-MP Land Surface Model | Modeling Software | Atmosphere | A community, open-source land surface model that simulates terrestrial water and energy cycles, including evapotranspiration, which can be evaluated and improved for regional applications [6]. |

Ecological models are mathematical representations of ecological systems, serving as simplified abstractions of highly complex real-world ecosystems [12]. These models function as virtual laboratories, enabling researchers to simulate large-scale experiments that would be too costly, time-consuming, or unethical to perform in reality, and to predict the state of ecosystems under future conditions [12]. For beginners in research, understanding ecological modeling is crucial because it provides a systematic framework for investigating ecological relationships, testing hypotheses, and informing conservation and resource management decisions [13] [14].

The process of model building inherently involves trade-offs between generality, realism, and precision [15] [12]. Consequently, researchers must make deliberate choices about which system features to include and which to disregard, guided primarily by the specific aims they hope to achieve [12]. This guide focuses on a fundamental choice facing ecological researchers: the decision between employing a strategic versus a tactical modeling approach. Understanding this core distinction is essential for designing effective research that yields credible, useful results for both scientific advancement and practical application [13] [16].

Core Concepts: Strategic and Tactical Models

The distinction between strategic and tactical models represents a critical dichotomy in ecological modeling, reflecting different philosophical approaches and end goals [15] [14].

Strategic Models

Strategic models aim to discover or derive general principles or fundamental laws that unify the apparent complexity of nature [15]. They are characterized by their simplifying assumptions and are not tailored to any particular system [15]. The primary goal of strategic modeling is theoretical understanding—to reveal the fundamental simplicity underlying ecological systems. Examples include classic theoretical frameworks such as the theory of island biogeography or Lotka-Volterra predator-prey dynamics [15]. Strategic models typically sacrifice realism and precision to achieve greater generality, making them invaluable for identifying broad patterns and first principles [15] [12].

Tactical Models

In contrast, tactical models are designed to explain or predict specific aspects of a particular system [15] [16]. They are built for applied purposes, such as assessing risk, allocating conservation efforts efficiently, or informing specific management decisions [16]. Rather than seeking universal principles, tactical modeling focuses on generating practical predictions for defined situations [15]. These models are often more complex than strategic models and incorporate greater system-specific detail to enhance their realism and predictive precision for the system of interest, though this may come at the expense of broad generality [14] [16]. Tactical models are frequently statistical in nature, mathematically summarizing patterns and relationships from observational field data [16].

Table 1: Fundamental Distinctions Between Strategic and Tactical Models

| Characteristic | Strategic Models | Tactical Models |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Discover general principles and unifying theories [15] | Explain or predict specific system behavior [15] [16] |

| Scope | Broad applicability across systems [15] | Focused on a particular system or population [15] [16] |

| Complexity | Simplified with many assumptions [15] [12] | More complex, incorporating system-specific details [14] [16] |

| Validation | Qualitative match to noisy observational data [15] | Quantitative comparison to field data from specific system [16] |

| Common Applications | Theoretical ecology, conceptual advances [15] | Conservation management, risk assessment, resource allocation [16] |

A Decision Framework for Model Selection

Choosing between a strategic and tactical approach requires careful consideration of your research question, objectives, and context. The following diagram outlines a systematic decision process to guide this choice:

Key Decision Factors

Research Objectives and Questions

Your fundamental research objective provides the most critical guidance. Strategic models are appropriate for addressing "why" questions about general ecological patterns and processes, such as "Why does species diversity typically decrease with increasing latitude?" or "What general principles govern energy flow through ecosystems?" [15]. Conversely, tactical models are better suited for "how" and "what" questions about specific systems, such as "How will sea-level rise affect piping plover nesting success at Cape Cod?" or "What is the population viability of grizzly bears in the Cabinet-Yaak ecosystem under different connectivity scenarios?" [16].

Data Availability and Quality

The availability of system-specific data heavily influences model selection. Tactical models require substantial empirical data for parameterization and validation, often drawn from field surveys, GPS tracking, camera traps, or environmental sensors [16]. When such detailed data are unavailable or insufficient, researchers may need to begin with a strategic approach or employ habitat suitability index modeling that incorporates expert opinion alongside limited data [16]. Strategic models, with their simplifying assumptions, can often proceed with more limited, generalized data inputs [15].

intended Application and Audience

Consider who will use your results and for what purpose. If your audience is primarily other scientists interested in fundamental ecological theory, a strategic approach may be most appropriate [15]. If your work is intended to inform conservation practitioners, resource managers, or policy makers facing specific decisions, a tactical model that provides context-specific predictions is typically necessary [13] [14] [16]. Management applications particularly benefit from tactical models that can evaluate alternative interventions, assess risks, and optimize conservation resources [16].

Methodological Approaches and Best Practices

Strategic Modeling Methodologies

Strategic modeling often employs analytic models with closed-form mathematical solutions that can be solved exactly [12] [17]. These models typically use systems of equations (e.g., differential equations) to represent general relationships between state variables, with parameters representing generalized processes rather than system-specific values [15] [12]. The methodology emphasizes mathematical elegance and theoretical insight, often beginning with literature reviews to identify key variables and relationships [16]. Strategic models are particularly valuable in early research stages when system understanding is limited, as they help identify potentially important variables and relationships before investing in extensive data collection [15].

Tactical Modeling Methodologies

Tactical modeling typically follows a more empirical approach, beginning with field data collection through surveys, tracking, or environmental monitoring [16]. These data then inform statistical models that quantify relationships between variables specific to the study system. Common tactical modeling approaches include:

- Habitat Models: Including resource selection functions and species distribution models that predict species occurrence based on environmental variables [16].

- Population Models: Used to investigate population dynamics, viability, and responses to management interventions [16].

- Landscape Models: Employed to study connectivity patterns and population responses to landscape changes from disturbance or climate change [16].

Table 2: Common Tactical Model Types and Their Applications

| Model Type | Primary Purpose | Typical Data Requirements | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resource Selection Functions (RSFs) | Understand and predict habitat selection by individuals [16] | GPS tracking data, habitat classification GIS layers [16] | Identifying critical habitat types for maintenance through management [16] |

| Species Distribution Models (SDMs) | Predict patterns of species occurrence across broad scales [16] | Species occurrence records, environmental GIS variables [16] | Selecting sites for species reintroductions, protected area establishment [16] |

| Population Viability Analysis (PVA) | Assess extinction risk and investigate population dynamics [16] | Demographic rates (survival, reproduction), population structure [16] | Informing endangered species recovery plans, harvest management [16] |

| Landscape Connectivity Models | Study connectivity patterns and population responses to landscape change [16] | Landscape resistance surfaces, species movement data [16] | Planning wildlife corridors, assessing fragmentation impacts [16] |

Best Practices for Effective Modeling

Regardless of approach, several best practices enhance modeling effectiveness:

- Establish Clear Objectives: Begin with a precise statement of model objectives, including key variables, output types, and data requirements [14].

- Engage Stakeholders Early: For tactically-oriented research, collaborate with potential end-users throughout model development to ensure relevance and utility [13] [14].

- Balance Complexity with Purpose: Include only those features essential to your objectives, avoiding unnecessary complexity that doesn't serve the research question [14].

- Address Uncertainty Explicitly: Quantify and communicate uncertainty in model parameters, structure, and outputs [13].

- Validate with Independent Data: Test model predictions against data not used in model development whenever possible [12] [16].

- Document and Share Code: Publish model code to enhance transparency, reproducibility, and collective advancement [13].

Building effective ecological models requires both conceptual and technical tools. The following table outlines key resources for researchers embarking on modeling projects:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Ecological Modeling

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Programming Environments | R statistical computing environment [13] | Data analysis, statistical modeling, and visualization; extensive packages for ecological modeling (e.g., species distribution modeling) [13] |

| Species Distribution Modeling Software | Maxent [13] | Predicting species distributions from occurrence records and environmental data [13] |

| Ecosystem Modeling Platforms | Ecopath with Ecosim (EwE), Atlantis [18] | Modeling trophic interactions and energy flow through entire ecosystems [18] |

| GIS and Spatial Analysis Tools | ArcGIS, QGIS, GRASS | Processing spatial data, creating habitat layers, and conducting spatial analyses for habitat and landscape models [16] |

| Data Collection Technologies | GPS trackers, camera traps, acoustic recorders, environmental sensors [16] | Gathering field data on animal movements, habitat use, and environmental conditions for parameterizing tactical models [16] |

| Model Evaluation Frameworks | Cross-validation, sensitivity analysis, uncertainty analysis [13] [12] | Assessing model performance, reliability, and robustness [13] [12] |

The choice between strategic and tactical modeling represents a fundamental decision point in ecological research. Strategic models offer general insights and theoretical understanding through simplification, while tactical models provide specific predictions and practical guidance through greater system realism [15] [16]. By carefully considering your research questions, available data, intended applications, and the specific trade-offs involved, you can select the approach that best advances both scientific understanding and effective ecological management. For beginners, starting with clear objectives and appropriate methodology selection provides the strongest foundation for producing research that is both scientifically rigorous and practically relevant.

Ecological modeling employs mathematical representations and computer simulations to understand complex environmental systems, predict changes, and inform decision-making. For researchers and scientists in drug development and environmental health, these models provide indispensable tools for quantifying interactions between chemicals, biological organisms, and larger ecosystems. Modeling approaches allow professionals to extrapolate limited experimental data, assess potential risks, and design more targeted and efficient experimental protocols. This guide details three fundamental model types—population dynamics, ecotoxicological, and steady-state—that form the cornerstone of environmental assessment and management, providing a foundation for beginner researchers to build upon in both ecological and pharmacological contexts.

Steady-State Models

Theoretical Foundations and Historical Context

Steady-state models in cosmology propose that the universe is always expanding while maintaining a constant average density. This is achieved through the continuous creation of matter at a rate precisely balanced with cosmic expansion, resulting in a universe with no beginning or end in time [19] [20]. The model adheres to the Perfect Cosmological Principle, which states that the universe appears identical from any point, in any direction, at any time—maintaining the same large-scale properties throughout eternity [21] [20]. This theory was first formally proposed in 1948 by British scientists Hermann Bondi, Thomas Gold, and Fred Hoyle as a compelling alternative to the emerging Big Bang hypothesis [19].

Table: Key Principles of the Steady-State Theory

| Principle | Description | Proponents |

|---|---|---|

| Perfect Cosmological Principle | Universe is statistically identical at all points in space and time | Bondi, Gold, Hoyle [20] |

| Continuous Matter Creation | New matter created to maintain constant density during expansion | Fred Hoyle [19] |

| Infinite Universe | No beginning or end to the universe; eternally existing | Bondi, Gold [21] |

Key Predictions and Comparison with Big Bang Theory

The steady-state model predicts that the average density of matter in the universe, the arrangement of galaxies, and the average distance between galaxies remain constant over time, despite the overall expansion [19] [21]. To achieve this balance, matter must be created ex nihilo at the remarkably low rate of approximately one hydrogen atom per 6 cubic kilometers of space per year [21]. This contrasts sharply with the Big Bang theory, which posits a finite-age universe that has evolved from an incredibly hot, dense initial state and continues to expand and cool [20].

Observational Tests and Experimental Evidence

Several key observational tests ultimately challenged the steady-state model's validity. Radio source counts in the 1950s and 1960s revealed more distant radio galaxies and quasars (observed as they were billions of years ago) than nearby ones, suggesting the universe was different in the past—contradicting the steady-state principle [21] [20]. The discovery of quasars only at great distances provided further evidence of cosmic evolution [21]. The most critical evidence against the theory came with the 1964 discovery of the cosmic microwave background (CMB) radiation—a nearly uniform glow permeating the universe that the Big Bang model had predicted as a relic of the hot, dense early universe [20]. The steady-state model struggled to explain the CMB's blackbody spectrum and remarkable uniformity [21] [20].

Table: Observational Evidence Challenging Steady-State Theory

| Evidence | Observation | Challenge to Steady-State |

|---|---|---|

| Radio Source Counts | More distant radio sources than nearby ones | Universe was different in the past [20] |

| Quasar Distribution | Quasars only found at great distances | Suggests cosmic evolution [21] |

| Cosmic Microwave Background | Uniform background radiation with blackbody spectrum | Cannot be explained by scattered starlight [20] |

| X-Ray Background | Diffuse X-ray background radiation | Exceeds predictions from thermal instabilities [20] |

Modern Status and Research Applications

While the original steady-state model is now largely rejected by the scientific community in favor of the Big Bang theory, it remains historically significant as a scientifically rigorous alternative that made testable predictions [21] [20]. Modified versions like the Quasi-Steady State model proposed by Hoyle, Burbidge, and Narlikar in 1993 suggest episodic "minibangs" or creation events within an overall steady-state framework [20]. Despite its obsolescence in cosmology, the conceptual framework of steady-state systems remains highly valuable in other scientific domains, particularly in environmental modeling where the concept applies to systems maintaining equilibrium despite flux, such as chemically balanced ecosystems or physiological processes [22].

Population Dynamics Models

Fundamental Principles and Mathematical Formulations

Population dynamics models quantitatively describe how population sizes and structures change over time through processes of birth, death, and dispersal [23]. These models range from simple aggregate representations of entire populations to complex age-structured formulations that track demographic subgroups. The simplest is the exponential growth model, which assumes constant growth rates and is mathematically represented as ( P(t) = P(0)(1 + r)^t ) in discrete form or ( P(t) = P(0)e^{rt} ) in continuous form, where ( P(t) ) is population size at time ( t ), and ( r ) is the intrinsic growth rate [23]. The logistic growth model incorporates density dependence by reducing the growth rate as the population approaches carrying capacity ( K ), following the differential equation ( \frac{dP}{dt} = rP(1 - \frac{P}{K}) ) [23].

Advanced Modeling Frameworks

More sophisticated population models account for age structure, spatial distribution, and environmental stochasticity. Linear age-structured models (e.g., Leslie Matrix models) project population changes using age-specific fertility and survival rates [23]. Metapopulation models represent populations distributed across discrete habitat patches, with local extinctions and recolonizations [23]. Source-sink models describe systems where populations in high-quality habitats (sources) produce surplus individuals that disperse to lower-quality habitats (sinks) where mortality may exceed reproduction without immigration [23]. More complex nonlinear models incorporate feedback mechanisms, such as the Easterlin hypothesis that fertility rates respond to the relative size of young adult cohorts, potentially generating cyclical boom-bust population patterns [23].

Applications in Environmental Assessment

Population dynamics models provide critical tools for ecological risk assessment, particularly for evaluating how chemical exposures and environmental stressors affect wildlife populations over time [24]. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency employs models like Markov Chain Nest (MCnest) to estimate pesticide impacts on avian reproductive success and population viability [24]. These models help translate individual-level toxicological effects (e.g., reduced fecundity or survival) to population-level consequences, informing regulatory decisions for pesticides and other chemicals [24]. In landscape ecology, population models help understand how habitat fragmentation and land use changes affect species persistence across complex mosaics of natural and human-dominated ecosystems [25].

Table: Population Dynamics Model Types and Applications

| Model Type | Key Features | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Exponential Model | Constant growth rate; unlimited resources | Theoretical studies; short-term projections [23] |

| Logistic Model | Density-dependent growth; carrying capacity | Population projections; harvesting models [23] |

| Age-Structured Models | Tracks age classes; age-specific vital rates | Human demography; wildlife management [23] |

| Metapopulation Models | Multiple patches; colonization-extinction dynamics | Conservation in fragmented landscapes [23] |

| Source-Sink Models | High and low quality habitats connected by dispersal | Reserve design; pest management [23] |

Ecotoxicological Models

Conceptual Framework and Model Classification

Ecotoxicological models simulate the fate, transport, and effects of toxic substances in environmental systems, connecting chemical emissions to ecological impacts [22]. These models generally fall into two categories: fate models, which predict chemical concentrations in environmental compartments (e.g., water, soil, biota), and effect models, which translate chemical concentrations or body burdens into adverse outcomes on organisms, populations, or ecosystems [22]. These models differ from general ecological models through their need for parameters covering all possible environmental reactions of toxic substances and their requirement for extensive validation due to the potentially severe consequences of underestimating toxic effects [22].

Regulatory Applications and Methodological Approaches

Ecotoxicological models support a tiered risk assessment approach used by regulatory agencies like the U.S. EPA [24]. Initial screening assessments use rapid methods with minimal data requirements, while higher-tier assessments employ more complex models for chemicals and scenarios of greater concern [24]. These integrated models span the complete sequence of ecological toxicity events: from environmental release and fate/transport processes through exposure, internal dosimetry, metabolism, and ultimately toxicological responses in organisms and populations [24]. The EPA's Ecotoxicological Assessment and Modeling (ETAM) research program advances these modeling approaches specifically for chemicals with limited available data [24].

Specialized Modeling Tools and Databases

Several specialized tools and databases support ecotoxicological modeling and risk assessment:

- ECOTOX Knowledgebase: A comprehensive, continuously updated database containing toxicity and bioaccumulation information for aquatic and terrestrial organisms [24].

- SeqAPASS: A computational tool that predicts chemical susceptibility across species based on sequence similarity of molecular targets [24].

- Web-ICE: A tool for estimating acute toxicity to aquatic and terrestrial organisms using interspecies correlation equations [24].

- Species Sensitivity Distribution (SSD) Toolbox: Software that models the distribution of species sensitivities to chemical concentrations [24].

Case Studies and Research Frontiers

Ecotoxicological models have been successfully applied to diverse contamination scenarios. A model developed for heavy metal uptake in fish from wastewater-fed aquaculture in Ghana simulated cadmium, copper, lead, chromium, and mercury accumulation, supporting food safety assessments [22]. Another case study modeled cadmium and lead contamination pathways from air pollution, municipal sludge, and fertilizers into agricultural products, informing soil management practices [22]. Current research frontiers include modeling Contaminants of Immediate and Emerging Concern like PFAS chemicals, assessing combined impacts of climate change and chemical stressors, and developing approaches for cross-species extrapolation of toxicity data to protect endangered species [24].

Table: Essential Resources for Ecological Modeling Research

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| ECOTOX Knowledgebase | Comprehensive toxicity database for aquatic and terrestrial species | Chemical risk assessment; literature data compilation [24] |

| SeqAPASS Tool | Predicts chemical susceptibility across species via sequence alignment | Cross-species extrapolation; molecular initiating events [24] |

| Markov Chain Nest (MCnest) | Models pesticide impacts on avian reproductive success | Population-level risk assessment for birds [24] |

| Species Sensitivity Distribution Toolbox | Fits statistical distributions to species sensitivity data | Derivation of protective concentration thresholds [24] |

| Web-ICE | Estimates acute toxicity using interspecies correlation | Data gap filling for species with limited testing [24] |

| STELLA Modeling Software | Graphical programming for system dynamics models | Model development and simulation [22] |

Understanding population dynamics, ecotoxicological, and steady-state models provides researchers with essential frameworks for investigating complex environmental systems. While these model types address different phenomena—from cosmic evolution to chemical impacts on wildlife populations—they share common mathematical foundations and conceptual approaches. For beginner researchers, mastering these fundamental model types enables more effective investigation of environmental questions, chemical risk assessment, and conservation challenges. The continued development and refinement of these modeling approaches will be crucial for addressing emerging environmental threats, from novel chemical contaminants to global climate change, providing the predictive capability needed for evidence-based environmental management and policy decisions.

The Critical Link Between Modeling and Sustainable Ecosystem Management

Ecological modeling provides the essential computational and conceptual framework to understand, predict, and manage complex natural systems. For researchers entering this field, mastering ecological models is fundamental to addressing pressing environmental challenges including biodiversity loss, climate change, and ecosystem degradation. These mathematical and computational representations allow scientists to simulate ecosystem dynamics under various scenarios, transforming raw data into actionable insights for sustainable management policies. The accelerating pace of global environmental change has exposed a critical misalignment between traditional economic paradigms and planetary biophysical limits, creating an urgent need for analytical approaches that can integrate ecological reality with human decision-making [26].

The transition from theory to effective policy occurs through initiatives such as The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity (TEEB), which quantifies the social costs of biodiversity loss and demonstrates the inadequacy of conventional indicators like GDP when natural assets depreciate [26]. Ecological modeling provides the necessary tools to visualize these relationships, test interventions virtually before implementation, and optimize limited conservation resources. This technical guide introduces key modeling paradigms, detailed methodologies, and practical applications to equip beginning researchers with the foundational knowledge needed to contribute meaningfully to sustainable ecosystem management.

Core Modeling Approaches in Ecosystem Management

Conceptual Foundations and Typology

Ecological models for ecosystem management span a spectrum from purely theoretical to intensely applied, with varying degrees of complexity tailored to specific decision contexts. Understanding this taxonomy is the first step for researchers in selecting appropriate tools for their investigations.

Table 1: Classification of Ecosystem Modeling Approaches

| Model Category | Primary Function | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Scale | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ecological Process Models | Simulate biogeochemical cycles & population dynamics | Variable (site to regional) | Medium to long-term | Mechanistic understanding; Scenario testing |

| Empirical Statistical Models | Establish relationships between observed variables | Local to landscape | Past to present | Predictive accuracy; Data-driven insights |

| Integrated Assessment Models | Combine ecological & socioeconomic dimensions | Regional to global | Long-term to intergenerational | Policy relevance; Cross-system integration |

| Habitat Suitability Models | Predict species distributions & habitat quality | Fine to moderate | Current to near-future | Conservation prioritization; Reserve design |

The ecosystem-services framework has emerged as a vital analytical language that organizes nature's contributions into provisioning, regulating, supporting, and cultural services [26]. This framework traces how alterations in ecosystem structure and function propagate through service pathways to affect social and economic outcomes, making it particularly valuable for decision-makers who must compare and manage trade-offs [26]. Biodiversity serves as the foundational element in this architecture, where variation within and among species underpins productivity, functional complementarity, and response diversity, thereby conferring resilience to shocks intensified by climate change [26].

Quantitative Valuation Methods for Ecosystem Services

Assigning quantitative values to ecosystem services represents a crucial methodological challenge where ecological modeling provides indispensable tools. Two distinct valuation traditions serve different decision problems and must be appropriately matched to research contexts.

Table 2: Ecosystem Service Valuation Approaches for Modeling

| Valuation Method | Core Methodology | Appropriate Applications | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accounting-Based Exchange Values | Uses observed or imputed market prices; excludes consumer surplus | Natural capital accounting; Corporate disclosure; Macro-tracking | Does not capture welfare changes; Limited for non-market services |

| Welfare-Based Measures | Estimates changes in consumer/producer surplus using revealed/stated preference | Project appraisal; Cost-benefit analysis; Distributionally sensitive policy | Subject to methodological biases; Difficult to validate |

| Benefit Transfer Method | Applies existing valuations to new contexts using meta-analysis | Rapid assessment; Screening studies; Policy scenarios | Reliability constrained by ecological/socioeconomic disparities |

| Comparative Ecological Radiation Force (CERF) | Characterizes spatial flows of ecosystem services between regions | Ecological compensation schemes; Regional planning | Emerging methodology; Limited case studies |

Best practices require researchers to explicitly match their valuation method to their decision context, clearly communicate what each metric captures and omits, and quantify uncertainty using confidence intervals, sensitivity analysis, and scenario ranges [26]. The Total Economic Value (TEV) framework further decomposes values into direct-use, indirect-use, option, and non-use values, providing a comprehensive structure for capturing the full spectrum of benefits that ecosystems provide to human societies [26].

Experimental Protocols for Ecosystem Service Modeling

Integrated Modeling of Multiple Ecosystem Services

Protocol Objective: To quantify, map, and analyze relationships between multiple ecosystem services, traditional ecological knowledge, and habitat quality in semi-arid socio-ecological systems [27].

Methodological Framework:

- Ecosystem Service Selection: Identify eleven representative ecosystem services across four categories:

- Provisioning Services: Beekeeping potential, medicinal plants, water yield

- Regulating Services: Gas regulation, soil retention

- Supporting Services: Soil stability, nursing function (natural regeneration)

- Cultural Services: Aesthetics, education, recreation [27]

Field Data Collection: Implement systematic field measurements including:

- Vegetation structure and composition surveys

- Soil sampling for physical and chemical properties

- Hydrological measurements for water yield estimation

- Interviews with local communities for traditional ecological knowledge documentation [27]

Spatial Modeling Using InVEST: Utilize the Integrated Valuation of Ecosystem Services and Tradeoffs (InVEST) model suite with the following inputs:

- Land cover/land use maps derived from satellite imagery

- Digital Elevation Models (DEM) for topographic analysis

- Biophysical data (precipitation, evapotranspiration, soil properties)

- Management practice data from traditional knowledge interviews [27]

GIS Integration and Analysis: Process all spatial data using Geographic Information Systems (GIS) to:

- Map the spatial distribution of each ecosystem service

- Overlay traditional ecological knowledge with ecological capacity assessments

- Identify hotspots of ecosystem service provision and gaps in service delivery [27]

Structural Equation Modeling (SEM): Apply SEM to test direct and indirect relationships between social-ecological variables and ecosystem services, evaluating causal pathways and interaction effects [27].

Spatial Supply-Demand Mismatch Analysis for Ecological Compensation

Protocol Objective: To quantify spatial mismatches between ecosystem service supply and demand, estimate service flows, and calculate ecological compensation requirements [28].

Methodological Framework:

- Ecosystem Service Quantification: Model four key services using ecological-economic approaches:

- Carbon Sequestration: Calculated as Net Primary Production (NPP) using MODIS satellite data and process-based models

- Soil Conservation (SC): Estimated using the Revised Universal Soil Loss Equation (RUSLE) adapted to the study region

- Water Yield (WY): Computed using the water balance approach within the InVEST model

- Food Supply (FS): Calculated from agricultural productivity statistics and crop distribution maps [28]

Supply-Demand Analysis: Calculate differences between biophysical supply and socioeconomic demand using the following equations:

- Soil Conservation Value:

DSDSC = Σ(AsVa/(1000hρ)) + Σ(AsCiRiPi/100) + 0.24Σ(AsVr/ρ)where As represents gap between SC supply and demand, Va is annual forestry cost, h is soil thickness, ρ is soil capacity, Ci is nutrient content, Ri is fertilizer proportion, Pi is fertilizer cost, Vr is earthmoving cost [28] - Water Yield Value:

DSDWY = Wf × Pwywhere Wf represents gap between WY supply and demand, Pwy is price per unit reservoir capacity [28] - Carbon Sequestration Value:

DSDNPP = NPPf × Pnppwhere NPPf represents gap between NPP supply and demand, Pnpp is carbon price [28] - Food Supply Value:

DSDFS = FSf × Pfswhere FSf represents gap between FS supply and demand, Pfs is food price [28]

- Soil Conservation Value:

Service Flow Direction Analysis: Apply breakpoint models and field intensity models to characterize the spatial flow of ecosystem services from surplus to deficit regions, identifying compensation pathways [28].

Hotspot Analysis: Use spatial statistics to identify clusters of ecosystem service supply-demand mismatches and prioritize areas for policy intervention [28].

Ecosystem Service Modeling Workflow

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Ecosystem Service Modeling

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Modeling Software | InVEST Model Suite | Spatially explicit ecosystem service quantification | Mapping service provision, trade-off analysis |

| Geospatial Tools | GIS Platforms (QGIS, ArcGIS) | Spatial data analysis, visualization, and overlay | Habitat quality mapping, service flow direction |

| Statistical Packages | R, Python (scikit-learn, pandas) | Statistical analysis, machine learning, SEM | Relationship testing between ecological-social variables |

| Remote Sensing Data | MODIS, Landsat, Sentinel | Land cover classification, NPP estimation, change detection | Carbon sequestration assessment, vegetation monitoring |

| Field Equipment | GPS Units, Soil Samplers, Vegetation Survey Tools | Ground-truthing, primary data collection | Model validation, traditional knowledge integration |

| Social Science Tools | Structured Interview Guides, Survey Instruments | Traditional ecological knowledge documentation | Cultural service valuation, community preference assessment |

Integrating Traditional Knowledge with Scientific Modeling

Conceptual Framework for Knowledge Integration

The integration of traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) with scientific modeling represents a transformative approach to ecosystem management that bridges the gap between theoretical frameworks and practical implementation. TEK comprises the knowledge, values, practices, and behaviors that local, indigenous, and peasant communities have developed and maintained through their interactions with biophysical environments over generations [27]. This knowledge system provides critical insights into ecosystem functioning, species interactions, and sustainable resource management practices that may not be captured through conventional scientific monitoring alone.

Structural Equation Modeling has demonstrated that traditional ecological knowledge serves as the most significant factor influencing cultural and provisioning services, while habitat quality predominantly affects supporting and regulating services [27]. This finding underscores the complementary nature of these knowledge systems and highlights the value of integrated approaches. Furthermore, research shows that people's emotional attachment to landscapes increases with the amount of time or frequency of visits, establishing a feedback loop between lived experience, traditional knowledge, and conservation motivation [27].

Knowledge Integration Framework

Methodological Protocol for Knowledge Integration

Implementation Framework:

- Participatory Mapping: Engage local communities in identifying and mapping culturally significant landscapes, resource collection areas, and historically important sites using geospatial technologies.

Structured Knowledge Documentation: Conduct semi-structured interviews, focus group discussions, and seasonal calendars to systematically record traditional practices related to ecosystem management.

Knowledge Co-Production Workshops: Facilitate collaborative sessions where traditional knowledge holders and scientific researchers jointly interpret modeling results and develop management recommendations.

Validation and Refinement: Use traditional knowledge to ground-truth model predictions and refine parameterization based on local observations of ecosystem changes.

This integrated approach has demonstrated particular effectiveness in vulnerable socio-ecological systems such as the arid and semi-arid regions of Iran, where communities maintain rich indigenous knowledge capital despite facing increasing pressures from land use change, overexploitation, and climate change [27]. The documentation of indigenous knowledge, two-way training, and integration into assessment models can simultaneously promote social and ecological resilience while providing a sustainable development pathway for these regions [27].

Policy Implementation and Management Applications

Designing Effective Payment for Ecosystem Services (PES) Programs

Ecological modeling provides the evidentiary foundation for designing and implementing effective Payment for Ecosystem Services programs, which create economic incentives for conservation by compensating landowners for maintaining or enhancing ecosystem services. The outcomes of PES programs hinge on several critical design features that must be informed by robust modeling:

- Targeting: Identifying high-risk or high-benefit areas where conservation investments will yield the greatest returns in ecosystem service provision [26]

- Conditionality: Establishing enforceable agreements through credible monitoring and verification systems that track conservation performance [26]

- Payment Calibration: Setting compensation levels that foster additionality (genuine conservation gains) without inducing excessive rents (overpayment) [26]

- Equity Assessment: Tracking who participates and who benefits from PES programs to ensure fair distribution of costs and benefits [26]

Modeling approaches must explicitly account for leakage (displacement of damaging activities to other areas) and dynamic responses to incentives, requiring attention to counterfactuals and spillover effects [26]. Policy mixes that combine price-based tools like PES with regulatory guardrails and information instruments can mitigate the weaknesses of any single approach and support adaptive management as ecological and economic conditions evolve [26].

Forest Co-Management and Stakeholder Engagement Modeling

Forest co-management represents another critical application where behavioral modeling informs the implementation of sustainable ecosystem management. Research in the Yarlung Tsangpo River Basin demonstrates that local stakeholders' perceptions of forest co-management policies significantly shape their participation behaviors [29]. Structural equation modeling based on the Theory of Planned Behavior has identified several key factors influencing engagement:

- Procedural Fairness: Perceptions of equitable decision-making processes strongly correlate with participation intentions [29]

- Institutional Trust: Confidence in implementing agencies predicts cooperation with management regulations [29]

- Cultural Inclusion: Gender and generational inclusion mediate community engagement, with male outmigration and ecological ranger programs creating new participatory dynamics [29]

- Transparent Benefit-Sharing: Clear understanding of economic and ecological benefits strengthens conservation behaviors [29]

These findings highlight the importance of incorporating socio-behavioral models alongside biophysical models to create effective governance systems that balance ecological conservation with human livelihoods.

Emerging Frontiers and Innovation in Ecosystem Modeling

Artificial Intelligence and Advanced Computational Approaches

Rapid advances in data science and computation are creating new possibilities for integrating ecological and economic analysis while introducing methodological risks that must be managed responsibly. Remote sensing and machine learning can sharpen spatial targeting, improve predictions of land-use change and species distributions, and enable near-real-time monitoring of conservation outcomes [26]. However, responsible practice requires attention to model interpretability, data provenance and licensing, and the computational and energy costs of analytic pipelines—considerations that are material for public agencies and conservation organizations operating under budget constraints [26].

Efficiency-aware workflows, appropriate baselines, and transparent communication about uncertainty can ensure that computational innovation complements rather than distorts ecological-economic inference [26]. Emerging approaches include:

- Deep Learning for Pattern Recognition: Automated identification of landscape features and changes from high-resolution imagery

- Natural Language Processing for Knowledge Extraction: Mining traditional ecological knowledge from historical records and oral history transcripts

- Reinforcement Learning for Adaptive Management: Optimizing conservation decisions through iterative learning from management outcomes

- Agent-Based Modeling for Complex Systems: Simulating interactions between human decisions and ecological processes across scales

Spatial Flow Modeling for Ecological Compensation

The concept of comparative ecological radiation force (CERF) represents an innovative approach to characterizing the spatial flow of ecosystem services and estimating compensation required to balance these flows [28]. Applied to the Tibetan Plateau, this methodology revealed distinctive flow patterns: net primary production (NPP), soil conservation, and water yield predominantly flowed from east to west, while food supply exhibited a north-to-south pattern [28]. These directional analyses enable more precise targeting of ecological compensation mechanisms that align financial transfers with actual service provision.

This approach addresses critical limitations in traditional compensation valuation methods, including the opportunity cost method (which varies based on cost carrier selection), contingent valuation method (inherently subjective), and benefit transfer method (constrained by ecological and socioeconomic disparities) [28]. By incorporating ecological supply-demand relationships and spatial interactions, this modeling framework more accurately captures the spatial mismatches between ES provision and beneficiaries, facilitating more balanced evaluation of ecological, economic, and social benefits [28].

From Theory to Practice: A Step-by-Step Modeling Methodology

Ecological modeling serves as a critical bridge between theoretical ecology and effective conservation policy, providing a structured framework for understanding complex biological systems and informing decision-making processes. This guide presents a comprehensive overview of the modeling lifecycle within ecological research, tracing the pathway from initial objective formulation through final model validation. By integrating good modeling practices (GMP) throughout this lifecycle, researchers can enhance model reliability, reproducibility, and relevance for addressing pressing biodiversity challenges. The structured approach outlined here emphasizes iterative refinement, documentation standards, and contextual adaptation specifically tailored for ecological applications, offering beginners in ecological research a robust foundation for developing trustworthy models that generate actionable insights for conservation.

Ecological modeling represents an indispensable methodology for addressing the complex, interconnected challenges of biodiversity loss, ecosystem management, and conservation policy assessment. These models function as stepping stones between research questions and potential solutions, translating ecological theory into quantifiable relationships that can be tested, validated, and applied to real-world conservation dilemmas [30] [31]. For beginners in ecological research, understanding the modeling lifecycle is paramount—it provides a structured framework that guides the entire process from conceptualization to application, ensuring that models are not just mathematically sound but also ecologically relevant and policy-useful.

The modeling lifecycle concept recognizes that models, like the data they incorporate, evolve through distinct developmental phases requiring different expertise and considerations [30]. This lifecycle approach is particularly valuable in ecological contexts where models must often integrate disparate data sources, account for dynamic environmental factors, and serve multiple stakeholders from scientists to policymakers. By adopting a lifecycle perspective, ecological researchers can better navigate the complexities of model development, avoid common pitfalls, and produce robust, transparent modeling outcomes that genuinely contribute to understanding and mitigating biodiversity loss.

The Modeling Lifecycle: Phases and Workflows

The ecological modeling process follows a structured, iterative pathway that transforms research questions into validated, actionable tools. This lifecycle encompasses interconnected phases, each with distinct activities, decisions, and outputs that collectively ensure the resulting model is both scientifically rigorous and practically useful for conservation applications.

Phase 1: Objective Formulation and Conceptualization

The initial and most critical phase establishes the model's purpose, scope, and theoretical foundations. Researchers must precisely define the research question and determine how modeling will address it—whether by capturing data variance, testing ecological processes, or predicting system behavior under different scenarios [30]. This requires deep contextual understanding of the ecological system, identified stakeholders, and intended use cases. The conceptualization process then translates this understanding into a conceptual model that diagrams key system components, relationships, and boundaries [32]. This conceptual foundation guides all subsequent technical decisions and ensures the model remains aligned with its original purpose throughout development.

Phase 2: Model Design and Selection

With objectives established, researchers design the model's formal structure and select appropriate modeling approaches. This involves choosing between mathematical formulations (e.g., differential equations for population dynamics), statistical models, or machine learning approaches based on the research question, data characteristics, and intended use [30]. A key decision at this stage is whether to develop new model structures or leverage existing models from the ecological literature that have proven effective for similar questions [30]. Ecological modelers should consider reusing and adapting established models when possible, as this facilitates comparison with previous studies and builds on validated approaches rather than starting anew for each application.

Phase 3: Data Preparation and Integration

Ecological models require careful data preparation, considering both existing datasets and prospective data collection. Researchers should evaluate data architecture—assessing how data is stored, formatted, and accessed—as these technical considerations significantly impact model implementation and performance [30]. Increasingly, ecological modeling leverages transfer learning, where models initially trained on existing datasets (e.g., species distribution data from one region) are subsequently refined with new, context-specific data [30]. This approach is particularly valuable in ecology where comprehensive data collection may be time-consuming or resource-intensive, allowing model development to proceed while new ecological monitoring is underway.

Phase 4: Model Implementation and Parameterization

This phase transforms the designed model into an operational tool through coding, parameter estimation, and preliminary testing. Implementation requires selecting appropriate computational tools and programming environments specific to ecological modeling needs [30]. Parameter estimation draws on ecological data, literature values, or expert knowledge to populate the model with biologically plausible values. Documentation is crucial at this stage; maintaining a transparent record of implementation decisions, parameter sources, and code modifications ensures reproducibility and facilitates model debugging and refinement [32]. The TRACE documentation framework (Transparent and Comprehensive Ecological Modeling) provides a structured approach for capturing these implementation details throughout the model's lifecycle [32].

Phase 5: Model Validation and Analysis

Validation assesses how well the implemented model represents the ecological system it aims to simulate. This involves multiple approaches: comparison with independent data not used in model development; sensitivity analysis to determine how model outputs respond to changes in parameters; and robustness analysis to test model behavior under varying assumptions [32]. For ecological models, validation should demonstrate that the model not only fits historical data but also produces biologically plausible projections under different scenarios. Performance metrics must be clearly reported and interpreted in relation to the model's intended conservation or management application [32].

Phase 6: Interpretation and Application

The final phase translates model outputs into ecological insights and conservation recommendations. Researchers must contextualize results within the limitations of the model structure, data quality, and uncertainty analyses [32]. Effective interpretation requires clear communication of how model findings address the original research question and what they imply for conservation policy or ecosystem management [31]. This phase often generates new questions and identifies knowledge gaps, potentially initiating another iteration of the modeling lifecycle as understanding of the ecological system deepens.

The following workflow diagram visualizes these interconnected phases and their key activities:

Quantitative Data Presentation: Model Comparison Framework

Structured comparison of ecological models requires standardized evaluation across multiple performance dimensions. The following tables provide frameworks for assessing model suitability during the selection phase and comparing validation results across candidate models.

Table 1: Ecological Model Selection Criteria Comparison

| Model Type | Data Requirements | Computational Complexity | Interpretability | Best-Suited Ecological Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Process-Based Models | Moderate to high (mechanistic parameters) | High | High | Population dynamics, ecosystem processes, nutrient cycling |

| Statistical Models | Moderate to high (observed patterns) | Low to moderate | Moderate to high | Species distributions, abundance trends, habitat suitability |