Unveiling Ecological Networks: A Guide to Molecular Techniques for Food Web Analysis

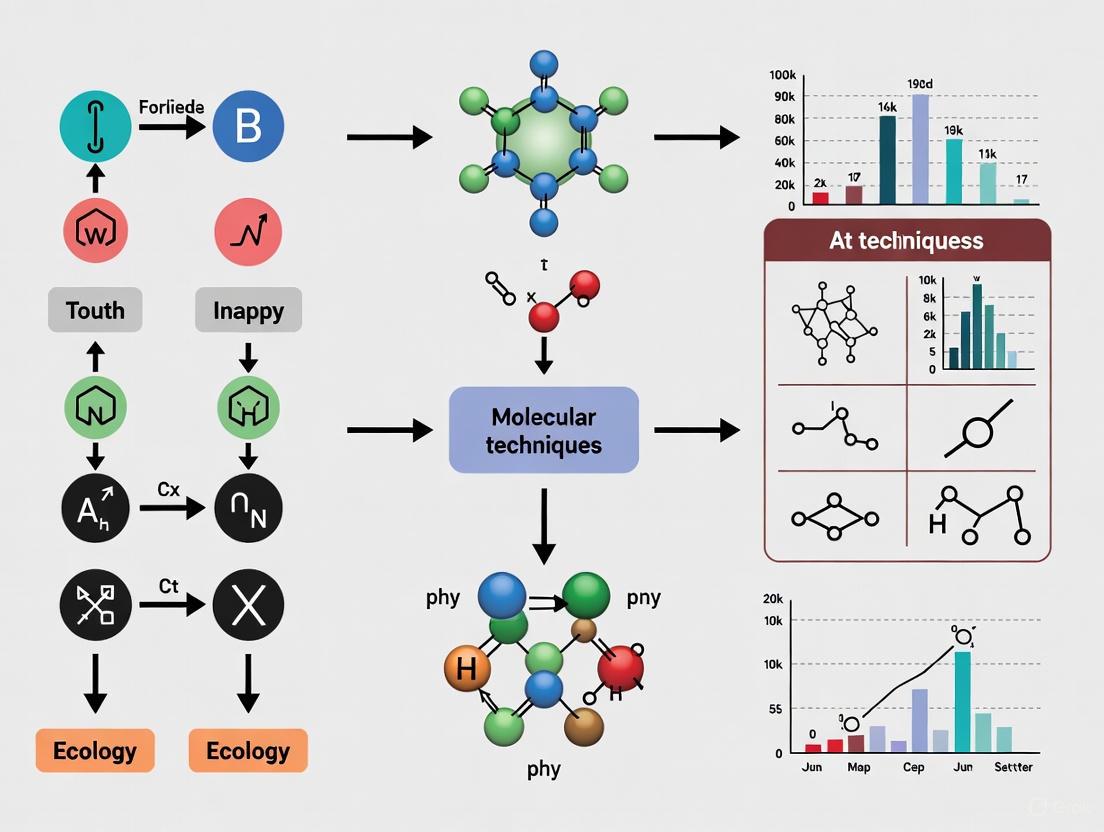

This article provides a comprehensive overview of molecular techniques revolutionizing food web ecology.

Unveiling Ecological Networks: A Guide to Molecular Techniques for Food Web Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of molecular techniques revolutionizing food web ecology. It explores the foundational principles of DNA-based methods, details specific protocols from DNA metabarcoding to stable isotope analysis, and addresses key challenges in troubleshooting and optimization. By comparing the strengths and limitations of various techniques and highlighting their validation through multi-method approaches, this guide serves as an essential resource for researchers aiming to accurately reconstruct and quantify trophic interactions in complex ecosystems, from agricultural landscapes to coral reefs.

The Molecular Revolution in Food Web Ecology: From Microscopy to DNA

For decades, visual gut content analysis (VGCA) was a foundational tool for ecologists studying food webs. This method involves the morphological identification of prey remains within the digestive tracts of consumers. While it has provided valuable insights, VGCA is constrained by its limited resolution, sensitivity, and quantitative capacity. The advent of molecular techniques has revolutionized this field, enabling researchers to uncover trophic interactions with unprecedented detail and accuracy. This document outlines the key limitations of traditional methods and provides detailed protocols for implementing modern molecular approaches in food web research, framed within the context of a broader thesis on molecular ecology.

Limitations of Visual Gut Content Analysis

The following table summarizes the principal constraints of VGCA, which have prompted the shift towards molecular methods.

Table 1: Key Limitations of Visual Gut Content Analysis

| Limitation | Description | Impact on Food Web Research |

|---|---|---|

| Taxonomic Resolution | Identification is often only possible to the order or family level, rarely to species [1]. Prey is often digested beyond visual recognition [2]. | Food webs are oversimplified, missing critical species-specific interactions and intra-guild predation [2]. |

| Quantitative Ability | Poor ability to quantify the relative importance of different prey items; soft-bodied prey are digested rapidly and are underestimated [3]. | Inaccurate assessment of energy flow, predator diet breadth, and the true ecological role of species. |

| Time-Consuming Process | Requires high expertise in morphology and is intrinsically complex and time-consuming [1]. | Limits the scale and replication of studies, resulting in scarce data, especially for complex ecosystems [1]. |

| Inability to Detect Scavenging | Cannot distinguish between predation on live prey and scavenging on dead material. | Misrepresentation of a species' trophic level and feeding behavior [2]. |

| Temporal Dynamics | Provides only a single snapshot of a meal, missing diel and seasonal shifts in diet [3]. | Fails to capture the dynamic nature of food webs and behaviorally constrained vs. free periods [3]. |

Molecular Methodologies: Experimental Protocols

Molecular techniques address the limitations of VGCA by detecting prey DNA or using stable isotopes to trace nutrient flow. Below are detailed protocols for two key approaches.

Protocol: DNA Barcoding for Trophic Interaction Analysis

This protocol uses polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to amplify a standardized gene region (e.g., COI) from predator gut contents to identify prey species [2] [4].

2.1.1. Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for DNA Barcoding

| Item | Function | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kit | Isolate total DNA from gut content samples. | Kits with inhibitors removal for complex samples. |

| Species-Specific Primers | Amplify DNA of a target prey species with high specificity [2]. | Designed for COI gene of a specific aphid pest [2]. |

| Universal COI Primers | Amplify a broad range of prey DNA for meta-barcoding. | Standard primers like LCO1490/HCO2198. |

| PCR Master Mix | Contains DNA polymerase, dNTPs, and buffer for amplification. | Commercially available mixes. |

| Agarose Gel | Electrophoresis medium to separate and visualize DNA fragments by size. | --- |

| Restriction Enzymes | For RFLP analysis; hydrolyze DNA at specific sites to generate species-specific fragment patterns [4]. | Used to distinguish between closely related fish species [4]. |

| Sanger or NGS Sequencing | Determine the DNA sequence of amplified products for identification. | NGS enables high-throughput multi-species detection. |

2.1.2. Step-by-Step Workflow

- Sample Collection and Preservation: Collect predator specimens in the field. Immediately preserve gut contents in 95% ethanol or DNA/RNA shield buffer to prevent DNA degradation. Store at -20°C.

- DNA Extraction: Using a commercial kit, homogenize the gut content sample and follow the manufacturer's protocol for tissue DNA extraction. Include a negative control (no tissue) to monitor contamination.

- PCR Amplification:

- For single-species detection: Use species-specific primers in a PCR reaction [2].

- For multi-species detection (meta-barcoding): Use universal primers.

- Reaction Setup: Prepare a 25 µL mix: 12.5 µL PCR Master Mix, 1 µL forward primer (10 µM), 1 µL reverse primer (10 µM), 2 µL DNA template, and 8.5 µL Nuclease-Free Water.

- Thermocycling Conditions: Initial denaturation: 95°C for 5 min; 35 cycles of: Denaturation: 95°C for 30 sec, Annealing: (Primer-specific Tm) for 30 sec, Extension: 72°C for 1 min; Final extension: 72°C for 7 min; Hold at 4°C.

- Product Analysis:

- Gel Electrophoresis: Resolve 5 µL of PCR product on a 1.5% agarose gel. A band of the expected size indicates a positive detection.

- Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism (RFLP): For confirmation, hydrolyze the PCR product with a restriction enzyme and run the fragments on a gel to observe a species-specific banding pattern [4].

- Sequencing: For meta-barcoding, purify PCR products and submit for high-throughput sequencing. Bioinformatic pipelines compare sequences to reference databases (e.g., BOLD, GenBank) for identification.

DNA Barcoding for Prey Identification

Protocol: Stable Isotope Analysis for Trophic Positioning

This protocol uses the natural abundance of stable isotopes (e.g., Nitrogen-15, Carbon-13) to determine the trophic level of organisms and trace energy sources through the food web [2].

2.2.1. Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Stable Isotope Analysis

| Item | Function | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Lyophilizer (Freeze-dryer) | Removes water from samples without altering isotopic signatures. | Essential for preparing solid tissue samples. |

| Ball Mill or Mortar & Pestle | Homogenizes dried samples into a fine, consistent powder. | --- |

| Elemental Analyzer | Combusts the sample to convert elements into simple gases (e.g., N₂, CO₂). | Coupled directly to the isotope ratio mass spectrometer. |

| Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometer (IRMS) | Precisely measures the ratio of heavy to light isotopes in the sample gases. | Provides δ¹⁵N and δ¹³C values. |

| Ultra-Pure Tin Capsules | Encapsulates powdered samples for combustion in the elemental analyzer. | --- |

| Reference Standards | Calibrates the IRMS and ensures data accuracy and comparability. | Internationally recognized standards (e.g., USGS40). |

2.2.2. Step-by-Step Workflow

- Sample Collection and Preparation: Collect tissue samples (e.g., muscle, whole invertebrates) from predators and potential prey/base resources. Rinse with deionized water to remove contaminants. Freeze samples at -80°C, then lyophilize for 48 hours or until completely dry.

- Homogenization: Grind the dried tissue to a homogeneous fine powder using a ball mill or mortar and pestle.

- Weighing and Encapsulating: Precisely weigh ~1 mg of powdered sample into a ultra-pure tin capsule. Fold the capsule into a compact pellet. Run laboratory reference standards after every 10-12 samples.

- Isotopic Analysis: Load samples, standards, and blanks into the auto-sampler of the Elemental Analyzer-Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometer (EA-IRMS) system.

- The EA combusts the sample at high temperature, converting nitrogen to N₂ and carbon to CO₂.

- The IRMS measures the ratio of ¹⁵N/¹⁴N and ¹³C/¹²C, reported as δ¹⁵N and δ¹³C values in parts per thousand (‰).

- Data Interpretation:

- Trophic Level Calculation: δ¹⁵N values exhibit a predictable enrichment (~3.4‰) with each trophic transfer. Trophic level is calculated based on the consumer's δ¹⁵N value relative to a baseline organism (e.g., primary consumer).

- Carbon Source: δ¹³C values change little (~1‰) with trophic level, helping to identify the primary carbon source (e.g., C3 vs. C4 plants, aquatic vs. terrestrial production).

Stable Isotope Analysis Workflow

Integrated Application: Temporal Food Web Dynamics

Molecular gut content analysis (MGCA) enables the construction of high-resolution, time-series food webs. A recent study in cereal fields used MGCA to sample generalist predators and their prey every two weeks across a growing season [3]. This approach quantified "food web specialization" as a proxy for predator diet overlap. The study revealed that specialization was highest (predators behaviorally constrained) early and late in the season, and lowest (predators behaviorally free) in the middle when prey diversity was highest [3]. This temporal roadmap identifies critical windows where conservation biological control is most vulnerable and guides the timing of management interventions.

Molecular techniques have fundamentally transformed food web ecology by overcoming the profound limitations of visual gut content analysis. The protocols for DNA barcoding and stable isotope analysis detailed here provide researchers with powerful, reproducible methods to accurately quantify trophic interactions, determine trophic levels, and observe dynamic changes in food web architecture over time. The integration of these molecular tools is essential for advancing our mechanistic understanding of ecosystem functioning and resilience.

Understanding trophic interactions is fundamental to ecology, providing insight into energy flow, community structure, and ecosystem functioning. Traditional methods for studying diet, such as direct observation or stomach content analysis, often provide limited snapshots and can miss cryptic, rapidly digested, or assimilated food items [5]. Within the framework of molecular food web research, two powerful techniques have emerged to overcome these limitations: DNA-based analysis and stable isotope analysis (SIA).

The core principle underlying these methods is that consumers retain biochemical tracers from their diet. DNA metabarcoding identifies ingested food items by matching genetic sequences, while stable isotope analysis uses ratios of naturally occurring isotopes to reveal assimilated energy and nutrient sources and define trophic positions [5] [6] [7]. This application note details the protocols for these techniques and their integrative application in modern food web research.

DNA-Based Trophic Analysis

Core Principles and Workflow

Dietary DNA metabarcoding is the analysis of a sample from a host organism that could contain DNA from multiple food items. The technique is based on the isolation, amplification, and sequencing of DNA from heterogeneous samples like faeces, stomach contents, or swabs, followed by taxonomic identification by comparing the sequences against DNA barcode reference libraries [5]. This method provides short-term diet composition information, typically representing items consumed several hours to days before sampling, depending on digestion rates [5].

Table 1: Key Applications and Advantages of DNA Metabarcoding

| Application | Specific Advantage | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Identifying fragile prey | Improved detection of easily digested items | Gelatinous organisms identified in shark and pinniped diet [5] |

| Detecting prey with no hard parts | Identification of species that leave no other traces | Increased detection of flatfish and clupeids in pinniped faeces [5] |

| High-throughput analysis | Standardized assessment of thousands of consumers | Enables construction of detailed temporal food web series [3] |

| Increased taxonomic resolution | Discrimination of species-level diet items | Reveals fine-grained resource partitioning [8] |

Detailed Protocol: Dietary DNA Metabarcoding

This protocol is adapted from methodologies applied in marine vertebrate studies [5].

1. Sample Collection and Preservation

- Sample Types: Collect non-invasively from faeces or regurgitates, or directly from stomach contents, intestinal swabs, or gut homogenates.

- Preservation: Immediately preserve samples in >95% ethanol or store at -20°C or -80°C to inhibit DNA degradation. For field collection, ethanol is preferred.

2. DNA Extraction

- Use a commercial DNA extraction kit suitable for complex and degraded samples.

- Incorporate a negative extraction control (a blank with no sample) to monitor for contamination.

- Optional: Include a step to block host DNA amplification using peptide nucleic acid (PNA) clamps to increase the yield of prey DNA [5].

3. PCR Amplification and Library Preparation

- Primer Selection: Choose a primer set that amplifies a short, variable genomic region (a "barcode"). Common targets include COI for animals or 16S rRNA for bacteria. The choice is critical and depends on the taxonomic breadth of the expected diet [5].

- PCR Setup: Perform triplicate PCR reactions per sample to account for stochastic amplification. Include negative PCR controls.

- Indexing and Library Prep: Add dual indices and sequencing adapters to the amplified DNA during a second, limited-cycle PCR. Pool purified PCR products in equimolar ratios into a sequencing library.

4. High-Throughput Sequencing and Bioinformatic Analysis

- Sequencing: Run the library on an appropriate high-throughput sequencing platform.

- Bioinformatics Processing:

- Demultiplexing: Assign sequences to samples based on their unique indices.

- Quality Filtering & Clustering: Remove low-quality sequences and cluster them into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) or Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs).

- Taxonomic Assignment: Compare representative sequences from each OTU/ASV against a curated reference database (e.g., BOLD, GenBank) for identification.

Stable Isotope Trophic Analysis

Core Principles and Workflow

Stable isotope analysis is based on the predictable isotopic fractionation of elements as they move through food webs. The isotopic composition of a consumer's tissues reflects that of its diet, integrated over the tissue's turnover time [6]. Key elements include:

- Nitrogen (δ¹⁵N): Shows step-wise enrichment (~3-4‰) with each trophic transfer, making it a primary indicator of trophic position [6] [9].

- Carbon (δ¹³C): Undergoes minimal enrichment (~1‰), allowing it to trace the original carbon sources at the base of the food web (e.g., phytoplankton vs. macroalgae) [8] [6].

More advanced Compound-Specific Isotope Analysis (CSIA), particularly of amino acids (δ¹⁵N-AA), provides higher resolution by isolating specific compounds. It separates "source" amino acids (e.g., phenylalanine), which retain baseline δ¹⁵N, from "trophic" amino acids (e.g., glutamic acid), which show strong enrichment, allowing for more accurate trophic position calculation independent of the baseline [9].

Table 2: Key Stable Isotope Ratios and Their Ecological Interpretations

| Isotope Ratio | Typical Trophic Enrichment (Δ) | Primary Ecological Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| δ¹⁵N (Nitrogen) | +2.5‰ to +3.4‰ per level [6] | Trophic position estimation [6] | Variation exists; CSIA-AA improves accuracy [9] |

| δ¹³C (Carbon) | ~ +1‰ per level [6] | Tracing primary energy sources [8] | Can be confounded by lipid content [9] |

| δ¹⁵N Phenylalanine | ~ +0.5‰ [9] | Source amino acid, records baseline | Used in CSIA with Glu for trophic position [9] |

| δ¹⁵N Glutamic Acid | ~ +8‰ [9] | Trophic amino acid, strongly enriches | Used in CSIA with Phe for trophic position [9] |

Detailed Protocol: Bulk Stable Isotope Analysis

This protocol is based on methodologies from freshwater and marine food web studies [8] [10] [6].

1. Sample Collection and Preparation

- Tissue Sampling: For animals, typically collect muscle, liver, or whole-body tissue. Liver has a faster isotopic turnover than muscle, reflecting short-term diet [9].

- Pre-processing: Freeze-dry or oven-dry samples and grind them to a homogeneous powder.

- Lipid Extraction: Perform on samples with high lipid content (e.g., liver, fish) using organic solvents like a chloroform-methanol mixture, as lipids are depleted in ¹³C and can skew δ¹³C values [9].

- Acidification: Treat samples containing carbonates (e.g., shells, sediments) with acid fumes to remove inorganic carbon.

2. Mass Spectrometry Analysis

- Sample Loading: Precisely weigh (~1 mg) the prepared sample material into a small tin capsule.

- Combustion and Analysis: Load capsules into an elemental analyzer coupled to an isotope ratio mass spectrometer (EA-IRMS).

- Calibration: Calibrate results against international standards (e.g., V-PDB for carbon, AIR for nitrogen). Express results in delta (δ) notation as parts per thousand (‰).

3. Data Interpretation

- Trophic Position Calculation: For a consumer, TP = [(δ¹⁵Nconsumer - δ¹⁵Nbaseline) / TEF] + λ, where TEF is the trophic enrichment factor and λ is the trophic position of the baseline organism [6].

- Mixing Models: Use Bayesian models (e.g., MixSIAR, SIAR) to quantify the proportional contributions of different food sources to a consumer's diet, based on δ¹³C and δ¹⁵N values [8].

Integrated Applications and Reagent Solutions

Synergistic Applications in Food Web Research

The combined application of DNA and stable isotope analyses overcomes the limitations of either method alone, providing a comprehensive view of both ingested and assimilated diet.

- Refining Trophic Niche Partitioning: In herbivorous coral reef fishes, SIA revealed trophic partitioning among groups, while fatty acid biomarkers (a complementary technique to DNA) identified the specific contribution of diatoms and cyanobacteria, clarifying the assimilated nutritional sources behind the isotopic signatures [8].

- Tracking Temporal Food Web Dynamics: DNA analysis of generalist predators across a season quantified fluctuations in food web specialization, identifying "behaviorally constrained" periods with low predator diversity on pests and "behaviorally free" periods with high functional redundancy, which is critical for biological control planning [3].

- Unraveling Host-Parasite Trophic Dynamics: CSIA of amino acids in a stickleback-tapeworm system revealed minimal trophic position difference (<0.5) between host and parasite, indicating direct assimilation of host-derived amino acids and complex metabolic interactions that bulk SIA could not resolve [9].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Trophic Link Analysis

| Research Reagent / Essential Material | Critical Function in Protocol |

|---|---|

| High-Proteinase K | Digests proteins and nucleases during DNA extraction, critical for liberating and protecting DNA from complex samples. |

| Ethanol (95-100%) | Preserves tissue and faecal samples in the field by dehydrating and fixing biological material, preventing DNA degradation. |

| Taxon-Specific PCR Primers | Amplifies the target barcode region (e.g., COI, 18S) from a specific taxonomic group with high specificity and sensitivity. |

| Curated Reference Database (e.g., BOLD, GenBank) | Allows taxonomic assignment of unknown sequences by providing a library of validated barcode sequences. |

| Tin Capsules (for SIA) | Contain the prepared, homogenized sample powder for high-temperature combustion in the Elemental Analyzer. |

| International Isotope Standards | Calibrates the isotope ratio mass spectrometer, ensuring data are accurate and comparable across laboratories and studies. |

| Lipid Extraction Solvents (e.g., Chloroform-Methanol) | Removes lipids from animal tissues to prevent the underestimation of δ¹³C values in bulk SIA. |

| Acid (e.g., HCl) for Carbonate Removal | Treats samples containing inorganic carbonates to ensure δ¹³C values reflect only the organic component. |

DNA and stable isotope analyses form a powerful, complementary toolkit for deciphering the complex structure and dynamics of food webs. DNA metabarcoding excels at providing high-resolution, taxonomic lists of ingested items, while stable isotope analysis reveals the assimilated diet and trophic level over longer timeframes. The integration of these methods, and particularly the adoption of advanced techniques like CSIA of amino acids, allows researchers to move beyond simple diet descriptions to a mechanistic understanding of nutrient flows, ecological niches, and the impacts of anthropogenic change on entire ecosystems [8] [9] [7]. As reference databases and analytical models continue to improve, these molecular techniques will become even more indispensable for rigorous food web research.

Molecular techniques have revolutionized the study of food webs, enabling researchers to accurately trace trophic interactions, identify species, and characterize biodiversity. The mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (CO1) gene has emerged as a cornerstone genetic marker for these investigations. Its utility stems from specific molecular characteristics: it is a mitochondrial gene with a high mutation rate compared to nuclear genes, facilitating species discrimination, and is relatively easy to amplify due to its high copy number per cell [11] [12]. The establishment of the "Folmer region," a 648 basepair fragment at the 5' end of the CO1 gene, as a universal DNA barcoding marker for metazoans provided a standardized approach for species identification [11] [13]. This has been crucial for constructing comprehensive reference libraries, such as those by the Fish Barcode of Life Initiative (FISH-BOL) [13].

Beyond simple species identification, molecular analysis of the CO1 gene and other markers provides critical insights into food web dynamics. Research reveals that within-population genetic variation in key traits, such as growth rates and phenology, can influence predator-prey body size ratios and ultimately affect the connectance, interaction strengths, and stability of entire food webs [14]. The application of these molecular methods has therefore become fundamental for addressing complex ecological questions in agroecosystems and natural environments, providing a window into otherwise difficult-to-observe trophic relationships [2].

The CO1 Gene: Barcoding Regions and Technical Considerations

While the "Folmer region" is the traditional DNA barcode, recent research demonstrates that its performance is not universal across taxa. Amplification of this region can be challenging, and its third codon positions often experience nucleotide substitution saturation, which can blur species-level distinctions [11]. This has prompted the exploration of alternative regions within the CO1 gene.

Studies on odonates have revealed that a novel partition downstream of the Folmer region, referred to as CO1B, offers several advantages. This region shows a higher discriminating power between closely related sister taxa and exhibits high reproducibility in amplification [11]. Compared to the Folmer region and another mitochondrial gene, ND1 (NADH dehydrogenase 1), the CO1B partition demonstrated a superior potential for character-based DNA barcoding and more reliable discrimination at various taxonomic levels [11]. This supports the adoption of a layered barcode approach, where multiple genetic markers are used in concert to enhance the accuracy and resolution of species identification in complex ecological studies [11].

Table 1: Comparison of Mitochondrial DNA Barcoding Regions for Food Web Research

| Barcode Region | Gene | Length (approx.) | Primary Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Folmer Region | CO1 (5' end) | 650 bp | Standardized; Universal primers; Extensive reference databases [11] [13] | Amplification difficulties; Nucleotide saturation at 3rd codon positions [11] |

| CO1B Region | CO1 (internal) | ~650 bp | High discrimination of sister taxa; Highly reproducible amplification [11] | Less established reference database; Requires taxon-specific validation |

| ND1 | NADH dehydrogenase 1 | Varies | Useful complement to CO1; Applied in character-based barcoding [11] | Less commonly used as a primary barcode marker |

The following diagram illustrates the workflow for utilizing these markers in a layered barcoding approach to resolve food web structure:

Experimental Protocols for CO1 DNA Barcoding

This protocol details the steps for identifying species in food web samples via DNA barcoding of the CO1 gene, based on standardized methodologies [11] [13].

Sample Collection and DNA Extraction

- Sample Types: The protocol can be applied to tissue samples from predators (e.g., insect predators), prey items, stomach contents, or environmental DNA (eDNA) from water or soil. Non-invasive sampling is often feasible. Samples should be preserved in 70-98% ethanol until processing [11].

- DNA Extraction: Use a commercial DNA extraction kit suitable for the sample type (e.g., tissue, eDNA). The goal is to obtain high-purity, high-molecular-weight DNA. Follow the manufacturer's instructions, including optional RNase treatment. Validate extraction success using spectrophotometry (e.g., Nanodrop) or fluorometry (e.g., Qubit).

PCR Amplification of the CO1 Folmer Region

- Primer Cocktail: Use universal metazoan primers or taxon-specific primers if the universal primers fail. A common primer cocktail includes several primers to enhance amplification success across diverse taxa [13].

- Reaction Setup:

- Template DNA: 1-10 ng.

- Primers: 0.2 µM each.

- PCR Master Mix: Includes DNA polymerase, dNTPs, MgCl₂, and reaction buffer.

- PCR Conditions:

- Initial Denaturation: 94°C for 2-5 minutes.

- Denaturation: 94°C for 30-40 seconds.

- Annealing: 50-55°C for 30-60 seconds.

- Extension: 72°C for 45-60 seconds.

- Final Extension: 72°C for 5-10 minutes.

- Gel Electrophoresis: Verify amplification by running 5 µL of the PCR product on a 1-2% agarose gel. A successful reaction will show a single, bright band at approximately 650 bp.

Sequencing and Data Analysis

- PCR Cleanup: Purify the remaining PCR product using an enzymatic cleanup kit (e.g., ExoSAP-IT) to remove primers and dNTPs.

- Sanger Sequencing: Perform bidirectional sequencing (forward and reverse) using the same PCR primers.

- Sequence Assembly and Trimming: Use software (e.g., Geneious, CodonCode Aligner) to assemble contigs from the forward and reverse reads and trim low-quality bases and primers.

- Species Identification:

- Check the sequence for indels or stop codons to confirm it is a functional mitochondrial gene and not a nuclear pseudogene [13].

- Perform a BLAST search against the GenBank database or, preferably, query the curated Barcode of Life Data (BOLD) system.

- A sequence match of ≥99% to a reference barcode is typically considered a conspecific identification. Lower similarity may indicate a new species or a gap in the reference library.

Complementary Genetic Markers and Advanced Molecular Techniques

While CO1 is a powerful tool, a multi-marker approach often yields the most robust results. Furthermore, technological advancements have expanded the molecular toolkit available to food web researchers.

Other Genetic Markers

- Mitochondrial ND1: The NADH dehydrogenase 1 gene has been used as a complementary marker to CO1 in odonates and other taxa to overcome limitations of the Folmer region, providing an additional source of diagnostic characters [11].

- Microsatellites and ITS Regions: These markers are valuable for investigating population genetic structure and intra-species variation, which can reveal how genetic diversity within a population influences its ecological role and interactions within the food web [14].

Advanced Detection Methodologies

For the detection of specific foodborne pathogens or prey items, several advanced molecular techniques are employed:

Table 2: Advanced Molecular Methods for Pathogen and Prey Detection in Food Webs

| Method | Principle | Key Advantages in Food Web Context | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multiplex PCR (mPCR) | Amplification of multiple target DNA sequences in a single reaction using multiple primer pairs [15]. | Highly species-specific; Can detect multiple pathogens/prey simultaneously from a single sample [15]. | Primer interactions can cause low efficiency; Cannot distinguish between living and dead organisms [15]. |

| Real-Time Quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) | Quantitative monitoring of PCR amplification in real-time using fluorescent probes or dyes [15]. | High sensitivity and specificity; Quantifies target DNA; No post-PCR processing needed; Closed system reduces contamination [15]. | High cost; Requires technical skill; Difficult to design for multiple targets simultaneously [15]. |

| Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP) | Isothermal nucleic acid amplification using 4-6 primers targeting 6-8 regions of the gene [15]. | Rapid, sensitive, and specific; Does not require expensive thermal cyclers [15]. | Primer design is more complex than for conventional PCR. |

The relationship between the research question, the appropriate molecular tool, and the resulting ecological insight can be visualized as follows:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Molecular Food Web Research

| Item | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | Isolation of high-quality genomic DNA from diverse sample types (tissue, eDNA filters, gut contents). | Select kits designed for complex or degraded samples. Validation for inhibitor removal is critical. |

| CO1 Primer Cocktails | PCR amplification of the standard Folmer region (e.g., LCO1490/HCO2198) or other CO1 regions. | Use universal metazoan primers for broad surveys or taxon-specific primers for higher success in focal groups [11] [13]. |

| PCR Master Mix | Pre-mixed solution containing thermostable DNA polymerase, dNTPs, MgCl₂, and optimized buffer. | Enables robust and reproducible amplification. Hot-start polymerases are recommended to reduce non-specific amplification. |

| DNA Size Standard Ladder | Accurate sizing of PCR amplicons during gel electrophoresis verification. | Essential for confirming the successful amplification of the ~650 bp CO1 barcode fragment. |

| Sanger Sequencing Reagents | Cycle sequencing of purified PCR products for generating the DNA barcode sequence. | Outsourcing to a dedicated sequencing facility is often the most efficient option. |

| Positive Control DNA | DNA from a known species to validate the entire PCR and sequencing workflow. | Crucial for troubleshooting and ensuring reagent integrity. |

Applications and Impact on Food Web Science

The application of CO1 barcoding and related molecular techniques has generated significant insights into food web ecology and agroecosystem management.

Unveiling Trophic Interactions: Molecular tools have exposed surprisingly complex food webs within supposedly simplified agricultural landscapes. PCR-based DNA barcoding with species-specific primers has been used to reconstruct precise food webs, revealing the importance of alternative non-pest prey for sustaining predator populations [2]. This understanding is vital for effective conservation biological control programs.

Detecting Food Fraud and Ensuring Sustainability: DNA barcoding has been critically applied to investigate seafood mislabeling. A study on the South African market used CO1 barcoding to reveal that a significant portion of fish products were mislabeled, undermining sustainable seafood initiatives and consumer choice [13]. This forensic application ensures the integrity of the food chain and supports conservation efforts.

Linking Intraspecific Variation to Food Web Structure: Simulation studies suggest that genetic variation in key traits like growth rate and phenology within a predator population can alter the distribution of body sizes through time. This, in turn, affects predator-prey body size ratios, potentially increasing food web connectance, omnivory, and variation in interaction strengths, all parameters known to influence community stability [14].

Molecular techniques have revolutionized the study of food webs, providing unprecedented resolution for deciphering trophic interactions, energy pathways, and ecosystem functioning. These tools allow researchers to move beyond traditional methods that often relied on observational data or morphological identification of prey items, which can be impractical for small, digested, or highly processed materials. By analyzing specific molecular markers, including DNA and stable isotopes, scientists can now accurately trace energy flow, identify species interactions, and quantify trophic positions within complex ecosystems. This application note details four key methodologies—PCR, qPCR, DNA Metabarcoding, and Compound-Specific Isotope Analysis of Amino Acids (CSIA-AA)—that constitute the modern molecular toolkit for food web research, providing structured protocols and comparative data to guide researchers in their application.

The following table summarizes the core characteristics, primary applications, and key outputs of the four central techniques discussed in this note.

Table 1: Core Molecular Techniques for Food Web Research

| Technique | Core Principle | Primary Applications in Food Web Research | Key Output | Sample Materials |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCR | Amplification of specific DNA segments | Detection of specific species (pathogens, pests, prey) via targeted DNA sequences [16] [17] | Presence/Absence of a target DNA sequence | Tissue, gut contents, feces, processed food [18] |

| qPCR | Quantitative real-time monitoring of DNA amplification | Quantification of target DNA; absolute quantification of microbial loads or relative abundance in mixtures [19] [20] | Quantity of target DNA (e.g., gene copy number) | Enriched cultures, extracted DNA from various matrices [21] |

| DNA Metabarcoding | High-throughput sequencing of DNA barcodes from bulk samples | Unbiased identification of species composition in complex samples (e.g., gut contents, feces, soil) [22] [18] [23] | List of species present in a sample | Bulk samples like soil, scat, gut contents, frass [22] [23] |

| CSIA-AA | Measurement of nitrogen isotope ratios in individual amino acids | Precise estimation of trophic position and feeding relationships in marine and terrestrial organisms [24] | Trophic Position (TP) of an organism | Tissue (muscle, liver, etc.) |

Detailed Techniques, Protocols, and Applications

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)

3.1.1 Principle and Workflow The Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) is a foundational molecular technique for in vitro amplification of specific DNA segments. The process relies on thermal cycling to repeatedly denature DNA, anneal sequence-specific primers, and extend new DNA strands, resulting in an exponential increase in the target sequence [16]. Its high specificity allows for the detection of a single target species within a complex matrix, making it invaluable for verifying the presence of specific prey, pathogens, or contaminants within a food web sample [17].

3.1.2 Experimental Protocol

- Sample Preparation and DNA Extraction: Begin with 50 mg of sample material (tissue, gut content, or processed food). Homogenize the sample using a mortar and liquid nitrogen. Perform DNA extraction using a commercial plant or tissue DNA mini kit, following the manufacturer's instructions [18].

- PCR Reaction Setup: Prepare a master mix for each reaction containing:

- 1X Reaction Buffer

- 200 µM of each dNTP

- 0.5 µM of each forward and reverse primer

- 1.25 U of heat-stable DNA Polymerase (e.g., Taq polymerase)

- 1–100 ng of template DNA

- Nuclease-free water to a final volume of 25 µL [16].

- Thermal Cycling: Amplify the target DNA using a standard thermocycler program:

- Initial Denaturation: 94–95°C for 2–5 minutes.

- Amplification (30–40 cycles):

- Denaturation: 94–95°C for 30–45 seconds.

- Annealing: 50–65°C (primer-specific) for 30–60 seconds.

- Extension: 70–74°C for 60–90 seconds.

- Final Extension: 70–74°C for 5–10 minutes [16].

- Detection (End-point): Analyze the PCR products via agarose gel electrophoresis (e.g., 1.5% gel). Visualize the amplified DNA fragments by staining with fluorescent ethidium bromide and imaging under UV light [16].

Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qPCR)

3.2.1 Principle and Workflow Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qPCR) builds upon conventional PCR by enabling the real-time monitoring of DNA amplification during each cycle. This is achieved through fluorescent reporter molecules, such as non-specific DNA-binding dyes (e.g., SYBR Green I) or sequence-specific fluorescent probes (e.g., hydrolysis probes) [19]. The cycle at which the fluorescence crosses a predefined threshold (Quantification Cycle, Cq) is proportional to the starting quantity of the target DNA, allowing for precise quantification [19]. In food web research, this is crucial for quantifying microbial loads or the relative abundance of specific prey in a consumer's diet.

3.2.2 Experimental Protocol

- Sample Enrichment and DNA Extraction: For pathogen detection, add 25g of sample to 225ml of enrichment broth and incubate overnight (8-24 hours). Collect the enriched samples and extract DNA using a dedicated pathogen DNA extraction kit, which may include automated systems for consistency [16] [21].

- qPCR Reaction Setup: Use a pre-mixed master mix compatible with real-time detection. A typical 20 µL reaction contains:

- Real-Time Amplification and Analysis: Run the reaction in a real-time PCR instrument with a program similar to:

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 2–5 minutes.

- Amplification (40 cycles):

- Denaturation: 95°C for 15–30 seconds.

- Annealing/Extension & Data Acquisition: 60°C for 30–60 seconds.

- Generate a standard curve using samples with known target concentrations. The instrument software will calculate the quantity of the target in unknown samples based on their Cq values [16].

Table 2: Common qPCR Fluorescence Detection Chemistries

| Chemistry | Mechanism | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Specific Dyes(e.g., SYBR Green I) | Fluoresces when bound to double-stranded DNA [19] [16] | Inexpensive; flexible for different primer sets [19] | Less specific; can bind to non-target products (e.g., primer-dimers) [19] [16] |

| Hydrolysis Probes(e.g., TaqMan) | Probe cleavage during amplification separates reporter from quencher [19] [16] | High specificity; suitable for multiplexing [19] [16] | More expensive; requires specific probe design [19] |

DNA Metabarcoding

3.3.1 Principle and Workflow DNA metabarcoding is a powerful approach that combines DNA barcoding with high-throughput sequencing (HTS) to identify the species composition of complex bulk samples. This technique involves extracting total DNA from an environmental sample (e.g., soil, gut contents, or feces), amplifying a short, standardized DNA barcode region (e.g., COI for animals, trnL for plants) using universal primers, and then sequencing the amplified products en masse [22] [18] [23]. Bioinformatics pipelines are used to cluster the sequences into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) and compare them to reference databases for identification. This method is particularly transformative for constructing detailed food webs and studying predator diets from fecal or gut content samples [23].

3.3.2 Experimental Protocol

- Sample Collection: Collect bulk samples (e.g., predator feces, insect frass, soil) directly into sterile tubes. Preserve samples immediately in 96% ethanol or freeze at -20°C to prevent DNA degradation [23].

- DNA Extraction and Amplification: Extract total genomic DNA from approximately 50 mg of homogenized sample using a commercial DNA extraction kit [18]. Amplify the target barcode region (e.g., trnL P6 loop for plants, COI for animals) in a PCR reaction using universal primers that include sequencing adapters.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Prepare the sequencing library from the amplified PCR products. Purify the library and quantify it accurately. Perform high-throughput sequencing on an appropriate platform (e.g., Illumina MiSeq/HiSeq) [18].

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Process the raw sequence data through a standardized pipeline:

Compound-Specific Isotope Analysis of Amino Acids (CSIA-AA)

3.4.1 Principle and Workflow Compound-Specific Isotope Analysis of Amino Acids (CSIA-AA) is a stable isotope technique that measures the nitrogen isotope ratios (δ¹⁵N) of individual amino acids in an organism's tissues. Its power derives from the differential isotopic fractionation of "trophic" and "source" amino acids during metabolism. Trophic amino acids (e.g., glutamic acid) undergo significant ¹⁵N enrichment with each trophic transfer, while source amino acids (e.g., phenylalanine) show minimal change [24]. This difference allows for precise estimation of an organism's trophic position without needing to know the isotopic baseline of the primary producers in the ecosystem.

3.4.2 Experimental Protocol

- Sample Preparation and Hydrolysis: Homogenize the tissue sample (e.g., muscle, liver). Precisely weigh a sub-sample (e.g., 0.5–1.0 mg) and place it in a hydrolysis tube. Hydrolyze the proteins into individual amino acids using strong acid (e.g., 6M HCl) under an inert atmosphere at high temperature (e.g., 110°C for 20–24 hours).

- Amino Acid Derivatization: Purify the hydrolysate and derivative the amino acids to make them volatile for gas chromatography. Common derivatization methods include esterification and acylation.

- Isotope Ratio Measurement: Inject the derivatized amino acids into a Gas Chromatograph (GC) coupled to an Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometer (IRMS). The GC separates the individual amino acids, which are then combusted to N₂ in the IRMS interface, and the δ¹⁵N value of each compound is measured.

- Trophic Position Calculation: Calculate the trophic position (TP) using the formula derived from the meta-analysis of marine organisms [24]:

- TP = [ (δ¹⁵NGlu - δ¹⁵NPhe) - β ] / TEF + 1

- Where:

- δ¹⁵NGlu and δ¹⁵NPhe are the measured values for glutamic acid and phenylalanine.

- β is the difference between Glu and Phe in primary producers (a meta-analysis found an average value of 6.6‰ for marine organisms, which may vary by ecosystem [24]).

- TEF is the trophic enrichment factor (the average value of 6.6‰ was found, which is lower than the previously applied 7.6‰ [24]).

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists essential reagents and kits for implementing the molecular techniques described in this application note.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Kits

| Item | Function | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Heat-Stable DNA Polymerase(e.g., Taq Polymerase) | Catalyzes the synthesis of new DNA strands during PCR amplification [16] | Core enzyme in both conventional and real-time PCR master mixes [16]. |

| Universal Primers for Barcode Regions(e.g., COI, trnL) | Amplify standardized gene regions from multiple species in a complex sample for metabarcoding [18] [23] | Identifying plant composition in processed food using the trnL P6-loop [18]. |

| Fluorescent Probes & Dyes(e.g., SYBR Green, Hydrolysis Probes) | Enable real-time detection and quantification of amplified DNA during qPCR [19] [16] | Differentiating target amplicons from non-specific products; multiplexing [19]. |

| Commercial DNA/RNA Extraction Kits | Isolate high-quality, amplifiable nucleic acids from complex sample matrices [21] | Isolating pathogen DNA from challenging foods (high fat, oil) for downstream qPCR [21]. |

| High-Throughput Sequencing Kit | Prepare amplified DNA barcodes for sequencing on platforms like Illumina [18] | Final library preparation for DNA metabarcoding to determine species composition. |

A Practical Toolkit: Deploying DNA Metabarcoding, qPCR, and Isotopic Analysis

DNA metabarcoding has revolutionized the study of food webs by enabling the simultaneous identification of multiple taxa from complex mixed samples. This molecular technique leverages high-throughput sequencing (HTS) to reveal trophic interactions with unprecedented resolution, allowing researchers to decipher predator-prey relationships, assess ecosystem biodiversity, and understand community dynamics without direct observation. By combining DNA barcoding principles with next-generation sequencing, metabarcoding provides a powerful tool for characterizing biological communities and their interactions through genetic analysis of environmental samples, predator gut contents, or feces. This application note details standardized protocols for implementing DNA metabarcoding in food web research, from experimental design through bioinformatic analysis.

The DNA metabarcoding process comprises six sequential stages: sample collection, DNA extraction, PCR amplification, sequencing, bioinformatic processing, and taxonomic assignment. Each stage requires careful consideration to ensure data quality and ecological validity [25]. The following workflow diagram illustrates the complete process:

Sample Collection Strategies

Effective sample collection is fundamental to successful metabarcoding studies. The choice of sample type depends on research objectives, target organisms, and ecosystem characteristics.

Sample Types and Applications

Table 1: Sample Collection Methods for Dietary and Biodiversity Studies

| Sample Type | Applications | Key Considerations | Example Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feces/Scat | Diet analysis of birds, mammals, and other predators | Non-invasive; reflects recently consumed prey; may contain degraded DNA | Parid bird diet analysis using nestling feces [23] |

| Environmental DNA (eDNA) | Biodiversity assessment in aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems | Samples DNA suspended in environment (water, soil, air); represents community composition | Fish diversity surveys in coastal waters [26] |

| Gut Contents | Direct analysis of predator diets | Invasive sampling; provides snapshot of recent consumption | Assessment of predator-prey interactions in agricultural systems [27] |

| Bulk Samples | Arthropod community characterization | Collection of entire organism assemblages using traps; requires morphological sorting | Malaise trap samples for insect diversity assessment [25] |

| Frass | Assessment of insect herbivore availability | Provides data on prey availability in ecosystem; links consumers to resources | Caterpillar community assessment through frass collection [23] |

Field Collection Protocols

Feces Collection: Collect fresh fecal samples using sterile tools and preserve immediately in 96% ethanol or specialized storage buffers. For nestling birds, collect entire fecal sacs and store in 5-ml plastic tubes with 96% ethanol [23].

Water Filtration for eDNA: Filter water through sterile membrane filters (typically 0.45-μm pore size). Pre-filtration through larger mesh sizes (80-595 μm) can prevent clogging and increase processed water volume. Store filters at -20°C in sterile containers [26].

Frass Collection: For herbivore availability studies, place funnel traps under host trees to collect frass. Count pellets and measure diameters to estimate biomass. Store dried or frozen until analysis [23].

DNA Extraction and Library Preparation

DNA Extraction Methods

DNA extraction should be optimized for sample type, considering potential inhibitors and DNA degradation levels. For feces and degraded samples, use extraction kits designed for difficult samples with inhibitor removal steps. Always include extraction controls to monitor contamination [25].

PCR Amplification Strategies

Primer selection is critical for successful metabarcoding. The following table compares common barcode regions used in dietary studies:

Table 2: DNA Barcode Markers for Metabarcoding Studies

| Marker Gene | Taxonomic Group | Amplicon Length | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COI (cytochrome c oxidase I) | Animals | ~650 bp (full); ~150-300 bp (mini) | Extensive reference databases; high discrimination power | Longer regions may amplify degraded DNA poorly |

| 16S rRNA | Bacteria, vertebrates | Variable | Useful for mammalian prey identification | Lower resolution than COI for some taxa |

| 12S rRNA | Vertebrates | ~100-200 bp | Highly conserved priming sites; good for degraded DNA | Limited taxonomic coverage for invertebrates |

| ITS (Internal Transcribed Spacer) | Plants, fungi | Variable | High discrimination in plants and fungi | Multiple copies can complicate quantification |

| rbcL | Plants | ~550 bp | Standard plant barcode; good reference databases | Lower variation than ITS for some groups |

| trnL | Plants | ~50-500 bp | Short primers work well with degraded DNA | Lower discrimination power than rbcL |

Library Preparation Approaches

Three principal strategies exist for preparing sequencing libraries:

One-Step PCR Approach: Uses fusion primers containing both target-specific sequences and sequencing adapters/indices in a single reaction. This streamlined approach is efficient but offers less flexibility in index combinations [28].

Two-Step PCR Approach: An initial PCR amplifies the target region with primers containing universal overhangs, followed by a second PCR that adds sequencing adapters and indices. This method increases multiplexing flexibility but may increase amplification bias [28].

Tagged PCR Approach: Incorporates sample-specific nucleotide tags during the metabarcoding PCR, positioned next to primers. This approach eliminates the need for library indices but requires careful primer design to avoid tag-jumping artifacts [28].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Dietary Analysis from Feces

This protocol adapts methods from Vesterinen et al. (2018) for analyzing insectivorous bird diets [23]:

Sample Collection: Collect fresh fecal samples from nestlings or captured birds using sterile tools. Place entire fecal sacs in 5-ml tubes filled with 96% ethanol. Store at -20°C until processing.

DNA Extraction:

- Use commercial DNA extraction kits designed for difficult samples (e.g., QIAamp PowerFecal Pro kit).

- Include negative extraction controls.

- Elute DNA in 50-100 μL elution buffer.

PCR Amplification:

- Amplify using mini-barcode primers (e.g., 157-bp fragment of COI) suitable for degraded DNA.

- Reaction mix: 2-10 μL template DNA, 0.5 μM each primer, 1× reaction buffer, 2.5 mM MgCl₂, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 1 U DNA polymerase.

- Cycling conditions: 94°C for 2 min; 35-40 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 48-52°C for 30 s, 72°C for 30 s; final extension at 72°C for 5 min.

Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Clean PCR products with magnetic beads.

- Quantify using fluorometric methods.

- Pool equimolar amounts of PCR products for sequencing on Illumina platforms (MiSeq or HiSeq).

Protocol 2: Prey Availability Assessment from Frass

This protocol enables parallel assessment of prey availability in the environment [23]:

Frass Collection: Place funnel traps (Ø 35 cm) under host trees. Collect frass in paper filters weekly. Count pellets and measure diameters for biomass estimation.

DNA Extraction and Amplification:

- Follow similar protocols as for feces, with increased sampling effort due to lower DNA concentration.

- Laboratory validation shows a minimum sample size threshold for successful detection.

Experimental Validation:

- Conduct controlled feeding experiments to establish detection limits.

- Test correlation between frass mass and DNA detection rates.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for DNA Metabarcoding

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | QIAamp PowerFecal Pro, DNeasy Blood & Tissue | Isolation of high-quality DNA from complex samples | Select kits with inhibitor removal for fecal samples |

| PCR Enzymes | High-fidelity DNA polymerases | Accurate amplification with low error rates | Reduces sequencing errors in final data |

| Barcoding Primers | MiFish-U, mini-COI, 12S-V5 | Taxon-specific amplification of target groups | Validate specificity and coverage for study system |

| Library Prep Kits | Illumina DNA Prep | Preparation of sequencing libraries | Compatibility with sequencing platform is essential |

| Quantification Kits | Qubit dsDNA HS Assay | Accurate DNA quantification | Fluorometric methods preferred over spectrophotometry |

| Size Selection Beads | AMPure XP beads | Removal of primer dimers and size selection | Critical for optimizing library size distribution |

| Negative Controls | Extraction blanks, PCR blanks | Monitoring contamination | Essential for quality control throughout workflow |

| Positive Controls | DNA from known species | Verification of PCR efficiency | Use species unlikely in study system |

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Bioinformatic Processing

Sequence processing typically involves: (1) demultiplexing by sample-specific barcodes, (2) quality filtering and trimming, (3) merging paired-end reads, (4) clustering sequences into Molecular Operational Taxonomic Units (MOTUs), and (5) taxonomic assignment against reference databases [25].

Methodological Considerations

Quantitative Interpretation: While metabarcoding data are semi-quantitative, read counts generally correlate with biomass in simple mixtures. However, amplification bias affects absolute quantification [27].

Spatial and Temporal Inference: eDNA detection represents presence in the environment, but the source organism may be upstream (aquatic systems) or previously present (persistent DNA). Scale of inference must be carefully considered [25].

Validation with Traditional Methods: Combine metabarcoding with traditional surveys where possible. One study found eDNA detected 61 fish species with only 41 detections in common with traditional surveys [26].

DNA metabarcoding provides researchers with a powerful methodological framework for deciphering trophic interactions and assessing biodiversity across ecosystems. By following standardized protocols for sample collection, DNA extraction, library preparation, and data analysis, scientists can generate comprehensive dietary profiles and characterize community composition with unprecedented resolution. The integration of metabarcoding with traditional ecological methods creates a robust approach for studying food web dynamics, particularly when complemented by environmental availability data from sources like frass samples. As reference databases expand and methodologies standardize, DNA metabarcoding will continue to transform our understanding of ecological networks and species interactions in both natural and managed ecosystems.

Within the framework of molecular techniques for studying food webs, quantitative PCR (qPCR) and multiplex PCR have emerged as powerful tools for decoding complex biological interactions. These techniques enable researchers to move from simply observing interactions to precisely quantifying them, offering unprecedented insights into the structure and dynamics of trophic networks. In food web research, understanding "who eats whom" and to what extent is fundamental. While traditional methods like microscopy or stable isotope analysis provide valuable snapshots, molecular approaches based on nucleic acid detection offer a higher degree of specificity, sensitivity, and throughput [2] [3]. The ability to simultaneously detect and quantify multiple targets in a single reaction makes multiplex qPCR particularly valuable for comprehensive ecological studies, allowing scientists to construct detailed interaction networks with limited sample material—a common constraint in field research [29] [3].

This application note explores the technical foundations, practical implementations, and specific applications of qPCR and multiplex PCR in targeted food web studies. We provide detailed protocols, data analysis frameworks, and reagent solutions to facilitate the adoption of these techniques in ecological and microbiological research, with a special emphasis on their utility in constructing and analyzing complex food webs.

Technical Foundations: qPCR and Multiplex qPCR

Basic Principles and Advantages

Quantitative PCR (qPCR), also known as real-time PCR, enables both the detection and quantification of specific DNA sequences through the monitoring of amplification reactions in real time. Unlike conventional PCR, which provides end-point analysis, qPCR tracks the accumulation of PCR products during each cycle of the amplification process, allowing for precise quantification of the initial template concentration [30]. The key output parameter is the quantification cycle (Cq), which represents the number of cycles required for the fluorescence signal to cross a threshold value significantly above the background. The Cq value is inversely proportional to the initial quantity of the target nucleic acid, serving as the basis for both absolute and relative quantification approaches [30].

Multiplex qPCR represents a significant advancement of this technology, enabling the simultaneous amplification and detection of two or more target sequences in a single reaction by utilizing multiple pairs of primers and probes labeled with distinct fluorescent dyes [29]. This approach offers several compelling advantages for food web research:

- Sample Conservation: By measuring multiple targets from a single well, multiplexing significantly reduces the amount of valuable sample required, which is particularly important when working with rare or difficult-to-obtain field specimens [29].

- Cost Efficiency: Amplifying multiple genes in a single well saves reagents and reduces the time required for experiment setup and data analysis [29].

- Improved Precision: Co-amplifying targets in the same well minimizes pipetting errors and well-to-well variation, as the genes to be compared share the same reaction environment [29].

- High-Throughput Capability: The ability to detect multiple targets simultaneously increases the scale and efficiency of food web studies, enabling researchers to process more samples and detect more interactions within the same timeframe [3].

Detection Chemistry and Probe Design

The success of multiplex qPCR relies heavily on the detection chemistry and careful probe design. The two most common detection systems in food microbiology are DNA-binding dyes and hydrolysis probes (TaqMan probes) [30]. While DNA-binding dyes offer a cost-effective solution, hydrolysis probes provide superior specificity and are more suitable for multiplex applications due to their target-specific nature.

For multiplex assays, each probe must be labeled with a different fluorescent dye that can be distinguished by the real-time PCR instrument. A typical dye combination might include FAM and VIC, whose emission spectra peak at 517 nm and 551 nm, respectively [29]. For higher levels of multiplexing (3-4 targets), additional dyes such as ABY (peak at 580 nm) and JUN (peak at 617 nm) can be employed [29]. The MCPC strategy allows for even higher levels of multiplexing by using multiple fluorophores to label different probes in a combinatorial manner [31].

Critical considerations for probe design include:

- TaqMan probes should have a melting temperature (Tm) approximately 10°C higher than the primers (approximately 68-70°C) [29].

- When using more than two targets, a combination of MGB-NFQ probes (for FAM and VIC) and QSY-quenched probes (for ABY and JUN) is recommended [29].

- Dyes with minimal spectral overlap should be selected, and dye intensity should be matched with target abundance (brightest dyes with low-abundance targets) [29].

Application in Food Web Research

Analyzing Trophic Interactions

Molecular assessment of food webs through techniques like multiplex PCR has revolutionized our understanding of trophic interactions in agricultural ecosystems. In a comprehensive study of invertebrate food webs in cereal fields, researchers used high-throughput multiplex PCR assays for molecular gut content analysis (MGCA) to examine the diets of thousands of generalist predators across an entire growing season [3]. This approach revealed dynamic changes in food web specialization throughout the season, with predators exhibiting more constrained diets during early and late season periods when prey availability was limited [3]. Such temporal mapping of trophic interactions provides unique insights into when management interventions might be most effective for biological pest control.

The application of these molecular tools has shown that supposedly simplified agricultural ecosystems actually host surprisingly complex food webs [2]. DNA-based methods have become the standard for studying these trophic interactions, with the COI gene emerging as the marker of choice due to the possibility of designing species-specific primers to detect predation on a variety of prey [2]. This approach is particularly suited to agricultural studies where the focus is often on the predation of one pest species by several potential predator species [2].

Tracking Microbial Dynamics in Food Systems

Beyond predator-prey interactions, qPCR and multiplex PCR have proven invaluable for tracking microbial dynamics in food systems, which represents another dimension of food web analysis. A recent study developed a multiplex TaqMan qPCR method for simultaneous detection of spoilage psychrotrophic bacteria in raw milk by targeting lipase (lipA) and protease (aprX) genes [32]. This approach demonstrated high specificity, with a sensitivity reaching up to 0.0002 ng/μL concentration of DNA, and a microbial load detection limit of 1.2 × 10² CFU/mL [32]. The ability to simultaneously detect multiple spoilage organisms provides a powerful tool for proactive quality control in the dairy supply chain.

Similarly, researchers have developed hydrolysis probe-based multiplex qPCR systems for simultaneous detection of eight common food-borne pathogens in a single reaction, utilizing a multicolor combinational probe coding strategy [31]. This approach enabled detection limits of less than 10 copies of DNA per reaction, providing a rapid and sensitive method for validating procedures to minimize or eliminate pathogen presence in food products [31].

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Representative Multiplex qPCR Applications in Food Web and Safety Research

| Application Area | Targets Detected | Detection Limit | Sample Matrix | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food-borne pathogen detection | Eight major bacterial pathogens | <10 DNA copies/reaction | Various food products | [31] |

| Spoilage bacteria quantification | lipA and aprX genes | 1.2 × 10² CFU/mL | Raw milk | [32] |

| Predator-prey interactions | Multiple prey species in gut contents | Varies by primer set | Field-collected predators | [3] |

Essential Reagent Solutions for Multiplex qPCR

Successful implementation of multiplex qPCR assays requires careful selection of reagents and master mixes specifically formulated to address the challenges of co-amplifying multiple targets. The following table outlines key research reagent solutions and their functions in multiplex qPCR experiments.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Multiplex qPCR Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| TaqMan Multiplex Master Mix | Optimized buffer for multiplex reactions | Formulated with Mustang Purple dye as passive reference to accommodate JUN dye in high-plex assays [29] |

| Hydrolysis Probes (TaqMan) | Target-specific detection with fluorescent reporters | FAM/VIC with MGB-NFQ quenchers; ABY/JUN with QSY quenchers for high-plex assays [29] |

| Primer/Probe Combinations | Specific amplification and detection | Typically 150-900 nM primers, 250 nM probes; may require optimization through primer limitation [29] |

| DNA Extraction Kits (e.g., QIACube HT) | Nucleic acid purification from complex matrices | Removes PCR inhibitors and concentrates targets; crucial for food and environmental samples [31] |

| Positive Control Templates | Assay validation and run quality control | Should cover all targets in multiplex assay; essential for specificity validation [33] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Sample Preparation and DNA Extraction

Proper sample preparation is critical for successful multiplex qPCR, particularly when working with complex matrices like food or gut content samples. The protocol below outlines an effective approach for sample processing:

Sample Homogenization: Homogenize samples using a Geno/Grinder or similar equipment to ensure uniform distribution of target organisms [31].

Pathogen Concentration: For food samples, implement a concentration step to isolate target organisms from relatively large sample sizes (e.g., 10g or 10mL). This typically involves filtration and high-speed centrifugation at 16,000 ×g for 5 minutes to sediment target cells [31].

Inhibitor Removal: Use commercial nucleic acid extraction systems (e.g., QIACube HT) according to manufacturer's instructions for tissue and bacteria to purify DNA and remove potential PCR inhibitors [31].

DNA Quantification and Quality Assessment: Measure the concentration and purity of extracted DNA using spectrophotometry (A260/A280 ratios). Store extracted nucleic acid at -80°C until use [31].

Template Preparation: Dilute DNA templates to appropriate working concentrations (typically 10-100 ng per reaction for genomic DNA) [34].

For artificial contamination studies in food matrices, spike sterile food samples with known concentrations of target organisms (e.g., 10¹ to 10³ CFU) in exponential growth phase to establish calibration curves and validate detection limits [31].

Multiplex qPCR Assay Setup and Optimization

The following protocol provides a framework for setting up and optimizing multiplex qPCR reactions:

Reagent Preparation: Defrost all reaction components on ice, protecting fluorescent probes from light exposure. Prepare primer and probe blends according to Table 3 [34].

Master Mix Assembly: Prepare a master mix sufficient for all reactions plus 10% extra to account for pipetting error. A typical 25 μL reaction might contain:

- 12.5 μL of 2× Multiplex Master Mix

- Primers and probes at optimized concentrations

- PCR-grade water

- 5 μL of DNA template [34]

Plate Setup: Aliquot 15-20 μL of master mix into each well, then add 5-10 μL of template DNA. Include no-template controls (NTCs) containing water instead of DNA template [34].

Centrifugation and Sealing: Centrifuge plates briefly to ensure all contents are at the bottom of wells. Seal plates with optical-quality seals [34].

Thermal Cycling: Run samples using an appropriate cycling protocol. A typical two-step protocol might include:

- Initial denaturation: 95°C for 2-10 minutes

- 40 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 15-30 seconds

- Annealing/Extension: 60°C for 30-60 seconds [34]

For assays requiring higher sensitivity, a three-step protocol with separate annealing and extension steps may be beneficial [34].

Table 3: Example Primer and Probe Blends for Multiplex qPCR

| Component | Initial Concentration | Final Concentration | Volume for 250 Reactions (μL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Forward Primer Mix | 100 μM | Varies (e.g., 150-900 nM) | 37.5-225 |

| Reverse Primer Mix | 100 μM | Varies (e.g., 150-900 nM) | 37.5-225 |

| Probe Mix | 100 μM | ~250 nM | 62.5 |

| PCR-grade Water | - | - | 225-487.5 |

| Total Volume | 750 |

Assay Validation and Quality Control

Thorough validation is essential for reliable multiplex qPCR results:

Specificity Testing: Verify that each primer/probe set amplifies only its intended target without cross-reactivity with non-target sequences [32].

Sensitivity and Limit of Detection: Determine the lowest concentration of target that can be reliably detected by testing serial dilutions of positive control templates [32].

Efficiency Validation: Ensure that amplification efficiencies for all targets fall within an acceptable range (90-110%) with R² values >0.990 for standard curves [32].

Singleplex vs. Multiplex Comparison: Confirm that results obtained from multiplex reactions match those from singleplex reactions for the same targets. If discrepancies are observed, optimize primer/probe concentrations to obtain the desired ΔCt values [29].

Reproducibility Assessment: Run all reactions in triplicate to evaluate precision. High variation between replicates may indicate the need for further optimization [29].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for a multiplex qPCR study in food web research, from sample collection to data analysis:

The molecular detection process in multiplex qPCR relies on specific probe hybridization and fluorescence emission, as visualized below:

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Quantification Approaches

Two primary quantification approaches are used in qPCR applications:

Absolute Quantification: This method determines the exact copy number or concentration of target DNA in a sample by comparing Cq values to a standard curve generated from known concentrations of the target sequence [30]. This approach is particularly useful for quantifying bacterial loads in food samples or determining the frequency of specific prey DNA in predator gut contents.

Relative Quantification: This approach measures the change in target quantity relative to a reference gene (endogenous control) under different experimental conditions [29]. The ΔΔCt method is commonly used, which normalizes the target Ct values to both a reference gene and a calibrator sample (e.g., control group) [29].

Troubleshooting Common Issues

Multiplex qPCR assays often face specific challenges that require optimization:

Competition for Reagents: When one target is significantly more abundant than others, it may consume disproportionate shares of nucleotides, enzymes, and other reagents. This can be addressed through primer limitation—reducing primer concentrations for abundant targets (e.g., from 900 nM to 150 nM) while maintaining probe concentrations at 250 nM [29].

Nonspecific Amplification: Primer-dimer formation or off-target amplification can be minimized by using multiple in silico tools to check for primer interactions and ensure amplicons do not overlap [29].

Spectral Overlap: Fluorescence spillover between channels can be reduced by selecting dye combinations with minimal spectral overlap and matching dye intensity with target abundance [29].

qPCR and multiplex PCR have fundamentally transformed our ability to quantify biological interactions in food web research. These techniques provide the sensitivity, specificity, and throughput necessary to decode complex trophic networks and microbial communities in diverse ecosystems. The protocols and guidelines presented in this application note offer researchers a framework for implementing these powerful molecular tools in their investigations of food web dynamics.

As molecular technologies continue to advance, we anticipate further refinements in multiplexing capabilities, detection sensitivity, and computational analysis tools. The ongoing development of automated digital PCR systems and improved in silico prediction tools for assay performance will further enhance our ability to quantify interactions within complex biological systems [33]. By integrating these molecular approaches with ecological theory, researchers can continue to unravel the intricate networks of interactions that underpin ecosystem structure and function.

Compound-specific stable isotope analysis of amino acids (CSIA-AA) has emerged as a powerful molecular technique that revolutionizes the study of food webs and energy pathways in ecological systems. Unlike traditional bulk stable isotope analysis, which provides averaged isotopic values across all compounds in a sample, CSIA-AA separates and measures the stable isotope values of individual amino acids, offering unprecedented resolution for tracing nutrient origins and transformations [35]. This advanced approach allows researchers to disentangle the complex interplay between baseline nutrient sources and trophic processes, addressing fundamental questions in ecology about energy flow, trophic relationships, and resource use in diverse ecosystems from agroecosystems to marine environments [2] [35] [3].

The technique leverages the distinct biochemical behavior of "trophic" versus "source" amino acids during metabolic processes. Trophic amino acids (e.g., glutamic acid) undergo significant isotopic fractionation with each trophic transfer, while source amino acids (e.g., phenylalanine) retain their original isotopic signature with minimal change [36] [35]. This differential fractionation provides a robust internal standard within organisms, enabling precise trophic position estimates and resource partitioning analysis that are less confounded by baseline isotopic variations that often plague bulk isotope approaches [35] [37].

Fundamental Principles of CSIA-AA

Biochemical Basis of Trophic Discrimination

The theoretical foundation of CSIA-AA rests on predictable patterns of isotopic fractionation during metabolic transformations of specific amino acids. When consumers metabolize dietary protein, trophic amino acids such as glutamic acid undergo deamination and transamination reactions that preferentially cleave lighter isotopes, resulting in progressive 15N enrichment at each trophic level—typically around 7-8‰ for the δ15NGlu - δ15NPhe trophic discrimination factor (TDF) [36]. Conversely, source amino acids like phenylalanine are incorporated with minimal isotopic alteration (Δ15N ~0‰) because their carbon skeletons are not extensively reconstituted during assimilation [36] [35]. This fundamental metabolic dichotomy creates the quantitative basis for calculating trophic positions independent of baseline variations:

Trophic Position (TP) = [(δ15NGlu - δ15NPhe - β) / TDF] + λ

Where β represents the difference between glutamic acid and phenylalanine in primary producers, TDF is the trophic discrimination factor, and λ is the trophic position of the primary producers [35].

Comparative Advantages Over Bulk SIA

CSIA-AA addresses several critical limitations inherent to bulk stable isotope analysis (bulk SIA). Bulk SIA convolves information about nutrient baselines with trophic processes, making it difficult to distinguish whether observed δ15N variations reflect true trophic differences or spatial/temporal heterogeneity in nutrient sources [35] [37]. This confounding effect is particularly problematic in systems with strong environmental gradients, such as coastal ecosystems with varying terrestrial inputs or agricultural systems with different fertilization regimes [35] [3].

By separately analyzing source and trophic amino acids, CSIA-AA effectively disentangles these factors, providing clearer insights into both the baseline nutrient sources supporting food webs and the trophic structure within them [35]. This dual-capability makes the technique especially valuable for studying systems where baseline isotopes vary substantially across space or time, including anthropogenically influenced ecosystems where human activities alter nutrient cycling [2] [37].

Key Application Areas with Experimental Protocols

Resolving Benthic Marine Food Webs

Experimental Protocol: Detrital Resource Incorporation in Wadden Sea Benthos

- Sample Collection: Collect representative specimens of benthic organisms (bivalves, polychaetes, crustaceans) and potential primary producer sources (microphytobenthos/MPB, phytoplankton, particulate organic matter) from intertidal zones. Immediately freeze specimens at -80°C until processing [35].

- Lipid Extraction and Hydrolysis: Freeze-dry tissue samples and homogenize. Extract lipids using dichloromethane:methanol (2:1 v/v) via Soxhlet extraction. Hydrolyze 5-10 mg of lipid-free tissue with 6N HCl at 110°C for 20 hours under nitrogen atmosphere to liberate individual amino acids [35].

- Amino Acid Derivatization and Purification: Convert liberated amino acids to N-acetyl methyl esters (NACME derivatives) or trifluoroacetic anhydride (TFAA) derivatives. Purify derivatives using liquid chromatography or solid phase extraction [38].