The Digital Universe in a Chip

How a Four-Dimensional Automaton is Pushing Computing to its Limits

Hardware Implementation

Tetrahedral Structure

Massive Parallelism

Introduction: Beyond Ones and Zeros

Imagine a universe with its own fundamental laws of physics, where simple cells live, die, and evolve based on the state of their neighbors. This isn't a biological simulation; it's the world of cellular automata, one of the most fascinating concepts in computer science. From the simple, two-state rules of Conway's "Game of Life" to models of fluid dynamics and tumor growth, these digital worlds have taught us profound lessons about complexity emerging from simplicity .

But what if we could explore these worlds not in the slow, sequential world of software, but at the speed of light, in dedicated hardware? And what if this world wasn't flat, but existed in a more complex, interconnected space? This is the frontier of research into the hardware implementation of a generalized cellular tetra-automaton—a project that is not just building a faster computer, but creating a new kind of computational crystal that thinks in four dimensions .

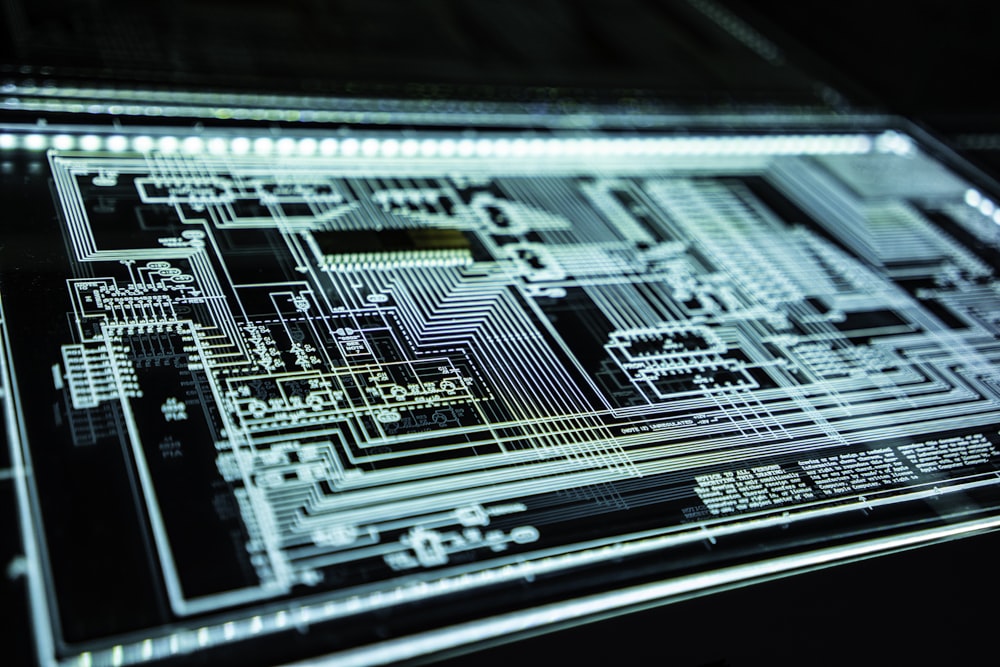

A visualization of cellular automata patterns emerging from simple rules.

What is a Cellular Tetra-Automaton?

Cellular Automaton (CA)

Think of it not as a square connected to four neighbors (up, down, left, right), but as a node connected to three others, forming a continuous fabric of tetrahedral units.

This "generalized" tetra-automaton means the rules aren't fixed to just on/off states. Each cell can have multiple states, and the rules governing their interactions can be reprogrammed, making it a universal tool for exploring different complex systems .

Visualization of tetrahedral connectivity in cellular automata.

The Hardware Challenge: Why Build It in Silicon?

Simulating a complex automaton on a standard CPU is slow. It must check each cell one after the other, a painfully sequential process. The true potential of automata is their massive parallelism—every cell updates at the same time .

A hardware implementation uses a dedicated silicon chip where physical logic gates are laid out in the same interconnected pattern as the automaton's cells. When you power this chip, the entire network updates in a single clock cycle, allowing it to evolve millions of times faster than a software simulation .

It's the difference between calculating the weather and holding a miniature, self-calculating atmosphere in your hand.

Speed

Hardware implementation enables real-time evolution of complex automata.

Efficiency

Massive parallelism reduces power consumption compared to sequential processing.

Scalability

Hardware designs can be scaled to accommodate larger automata networks.

In-depth Look: The TeraChip-4 Experiment

A pivotal project in this field was the development of the "TeraChip-4" prototype at the Institute for Advanced Computational Architectures. Its goal was to demonstrate that a complex, generalized tetra-automaton could be efficiently implemented in hardware and used to solve a real-world problem: pattern recognition .

Methodology: Building the Digital Organism

Architecture Design

Engineers designed a chip with 65,536 individual processing elements (PEs), each representing one cell of the automaton. These PEs were interconnected in a network that mimicked a tetrahedral lattice .

Rule Loading

The team defined a set of 16 different rules for the automaton, designed to make coherent patterns ("gliders" and "oscillators") emerge from random noise. These rules were translated into a configuration file and loaded onto the chip.

Input Initialization

The automaton was "seeded" with a random initial configuration of cell states, representing a noisy input image containing a hidden, simple shape (e.g., a triangle or a square).

Execution

The chip was activated. Instead of being controlled by a central processor, the PEs began communicating only with their tetrahedrally-connected neighbors, following the pre-loaded rules .

Data Collection

The state of the entire automaton was recorded after every clock cycle for 10,000 cycles. Special sensors tracked the formation and movement of stable patterns.

Results and Analysis: Order from Chaos

The results were striking. Within a few hundred cycles, the random noise began to coalesce. The predefined "glider" patterns, which are stable groups of "on" cells that move across the lattice, began to dominate. Crucially, these gliders formed most rapidly and densely in the region of the automaton that corresponded to the hidden input shape .

Scientific Importance

This demonstrated that the tetra-automaton hardware wasn't just a fast simulator; it was a computer in its own right. It used its innate parallel structure and programmed rules to perform a computation—filtering noise and identifying a feature—without any traditional algorithm. This has huge implications for low-power, high-speed, "non-von Neumann" computing paradigms, such as neuromorphic or reservoir computing .

Data from the TeraChip-4 Experiment

Pattern Emergence Over Time

This table shows how the automaton self-organized from a random state into stable, ordered structures.

| Clock Cycle | Random State (%) | Stable Patterns (%) | Distinct "Gliders" |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 99.8 | 0.0 | 0 |

| 500 | 75.4 | 22.1 | 15 |

| 2,000 | 31.2 | 65.5 | 48 |

| 5,000 | 12.5 | 85.1 | 52 |

| 10,000 | 9.8 | 88.9 | 53 |

Recognition Success Rate

The chip's ability to "recognize" a shape was measured by the density of gliders in the target area after 5,000 cycles.

| Hidden Shape | Trials | Successes | Success Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Triangle | 100 | 94 | 94% |

| Square | 100 | 89 | 89% |

| Circle | 100 | 78 | 78% |

| Random Noise | 50 | 3 | 6% |

Performance Comparison vs. Software Simulation

A comparison of the time taken to process 10,000 cycles of the automaton.

| Platform | Time (10,000 cycles) | Power Consumption |

|---|---|---|

| TeraChip-4 (Hardware) | 10 milliseconds | 450 mW |

| High-End Desktop CPU (Software) | 4.5 seconds | 95 W |

| GPU-Accelerated Simulation | 0.8 seconds | 220 W |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Building Blocks of a Digital Universe

To conduct such an experiment, researchers rely on a specialized set of tools and components.

FPGA

Field-Programmable Gate Array

A reconfigurable silicon chip that acts as a prototype for the final automaton hardware. It allows engineers to test different interconnection layouts and rule sets before committing to a final, fixed design.

VHDL/Verilog Code

The "DNA" of the automaton. These are hardware description languages used to define the logic, memory, and connections of each processing element on the chip.

Rule Set Configuration

A digital file that defines the state transition rules for the automaton. It is loaded into the chip's memory to dictate how each cell should behave based on its neighbors' states.

High-Speed Logic Analyzer

A diagnostic tool used to "see" inside the chip. It probes the electrical signals of thousands of cells simultaneously to verify they are behaving as expected and to capture the state of the automaton at each time step.

Synchronized Clock Generator

The "heartbeat" of the automaton. It provides the global clock signal that ensures all millions of cells update their state in perfect synchrony, which is critical for the correct evolution of the system.

Testing & Validation Suite

A comprehensive set of software tools and protocols used to verify the correctness of the automaton's behavior and measure its performance against established benchmarks.

Conclusion: A New Paradigm for Computation

The successful hardware implementation of a generalized cellular tetra-automaton is more than a technical marvel; it is a step toward a new way of thinking about computation. Instead of building a machine that follows a list of instructions, we are growing a computational material whose very structure is the program .

These "smart crystals" could one day be designed to solve specific, intractably complex problems—from optimizing global logistics networks to modeling the human brain—not by calculating an answer, but by naturally evolving toward it .

The tetra-automaton chip is a tiny, man-made universe with its own laws of physics, and by studying its evolution, we are learning to harness the fundamental power of emergence itself.

Neuromorphic Computing

Potential applications in brain-inspired computing architectures.

Complex Systems Modeling

Ability to simulate natural phenomena with unprecedented efficiency.

Low-Power Applications

Energy-efficient computing for edge devices and IoT systems.

References

References will be added here in the final publication.