Sustainable Intelligence: Optimizing Energy Use in AI-Powered Climate Solutions

This article examines the dual role of artificial intelligence as both a significant energy consumer and a powerful tool for climate innovation.

Sustainable Intelligence: Optimizing Energy Use in AI-Powered Climate Solutions

Abstract

This article examines the dual role of artificial intelligence as both a significant energy consumer and a powerful tool for climate innovation. It provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and scientific professionals, detailing the foundational energy and environmental costs of AI infrastructure, methodological applications of AI in climate science, strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing AI's energy footprint, and a comparative validation of its net environmental impact. The synthesis offers a critical pathway for leveraging AI's potential in biomedical and clinical research while advocating for a sustainable, energy-aware approach to its development and deployment.

The Dual Challenge: Understanding AI's Energy Footprint and Climate Potential

Troubleshooting Guides

Why is my AI model's operational carbon footprint higher than expected?

High operational carbon is often caused by running computations at times or in locations where the electricity grid relies heavily on fossil fuels. Operational carbon refers to emissions from the electricity consumed by processors (GPUs) during computation [1].

Diagnosis and Resolution:

- Analyze Your Grid's Carbon Intensity: Check the carbon intensity (gCO₂/kWh) of the local electricity grid where your data center is located. This intensity can vary significantly by time of day and season [1].

- Profile Computational Workloads: Use profiling tools to determine if your workloads are running during peak carbon intensity periods.

- Implement Carbon-Aware Scheduling: A core solution is to shift flexible, non-urgent computational tasks—such as model training runs or large batch inference jobs—to times when grid carbon intensity is lower (e.g., when solar or wind generation is high) [1]. The diagram below illustrates this scheduling logic.

How can I reduce the energy consumption of AI model training without significantly sacrificing accuracy?

A primary cause of excessive energy use is overtraining models, where a large portion of energy is spent on marginal accuracy gains [1].

Diagnosis and Resolution:

- Establish Accuracy-Efficiency Targets: Before training, define the minimum acceptable accuracy for your application. In many cases, a slightly lower accuracy is sufficient and dramatically more efficient [1].

- Implement Early Stopping: Monitor validation accuracy during training and halt the process once performance converges or meets your pre-defined target. Research indicates that about half of the electricity for training can be spent chasing the last 2-3% of accuracy [1].

- Use Hyperparameter Optimization (HPO) Wisely: Avoid running exhaustive, thousand-simulation HPO searches. Use more efficient HPO methods (like Bayesian optimization) or leverage insights from previously trained models to reduce wasted computing cycles [1].

My data center's Power Usage Effectiveness (PUE) is suboptimal. What are key areas for improvement?

A high PUE indicates that a large amount of energy is consumed by supporting infrastructure like cooling, rather than the computing IT equipment itself [2].

Diagnosis and Resolution:

- Audit Cooling Systems: Cooling can account for over 30% of energy use in less efficient facilities [2]. Examine the efficiency of your Computer Room Air Handling (CRAH) units and chilled water systems.

- Optimize GPU Power States: Research has shown that "turning down" GPUs to consume about three-tenths of the energy has minimal impacts on AI model performance and significantly reduces heat output, making cooling easier [1].

- Explore Advanced Cooling Technologies: For new builds or retrofits, consider more efficient cooling methods such as liquid immersion cooling or using naturally cool climates, as demonstrated by Meta's data center in Lulea, Sweden [1].

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the projected energy demand for AI and data centers in the coming years?

Forecasts show a significant increase in energy demand, though estimates vary. The table below summarizes key projections.

| Scope | Projected Energy Demand | Timeframe | Source & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| U.S. Data Centers | 426 TWh (133% growth from 2024) | 2030 | IEA Estimate [2] |

| U.S. Data Centers | 325 - 580 TWh (6.7% - 12% of U.S. electricity) | 2030 | Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory [3] |

| Global Data Centers | ~945 TWh (Slightly more than Japan's annual consumption) | 2030 | International Energy Agency (IEA) [1] |

What are the primary energy consumers within a typical data center?

The distribution of energy use within a data center is broken down as follows:

| Component | Average Energy Consumption | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| IT Servers (Compute) | ~60% on average [2] | This is the "useful" work. AI-optimized servers with powerful GPUs consume 2-4x more energy than traditional servers [2]. |

| Cooling Systems | 7% (efficient hyperscale) to >30% (less efficient facilities) [2] | A major target for efficiency gains and PUE improvement. |

| Other (Power Delivery, Lighting) | Remaining balance | Includes losses from power conversion and backup systems. |

How does the energy cost of AI model training compare to inference (operation)?

While model training is highly energy-intensive for a single event, the operational phase (inference) typically accounts for the bulk of a model's lifetime energy consumption due to its continuous, global use [4].

| Phase | Description | Energy Footprint |

|---|---|---|

| Training | The one-time process of creating an AI model on specialized hardware. | Extremely high for a single task. Training GPT-4 consumed an estimated 50 GWh [4]. |

| Inference | The ongoing use of the trained model to answer user queries (e.g., a ChatGPT question). | Estimated to be 80-90% of total computing power for AI. This represents the cumulative impact of billions of daily queries [4]. |

What are the most promising strategies for powering data centers with clean energy?

The industry is exploring a diverse portfolio of clean energy solutions to ensure reliability and decarbonize operations.

| Strategy | Description | Example Case Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Advanced Nuclear | Using small, modular nuclear reactors or micro-reactors located near data centers. | Equinix pre-ordered 20 "Kaleidos" micro-reactors from Radiant Industries [5]. |

| Next-Generation Geothermal | Tapping into geothermal heat with enhanced drilling techniques for constant, clean power. | Google's partnership with Fervo Energy for a geothermal project in Nevada [5]. |

| Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) | Corporations signing long-term contracts to buy power from new renewable energy farms. | Common practice among hyperscalers to fund new solar and wind projects [2]. |

| Carbon-Aware Computing | Technologically shifting computing workloads to times and locations with cleaner electricity [1]. | An area of active research at MIT and other institutions [1]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

For researchers quantifying and optimizing AI energy use, the following "reagents" and tools are essential.

| Tool / "Reagent" | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

GPU Power Monitoring Tools (e.g., nvidia-smi) |

Provides real-time and historical data on the power draw (in watts) of specific computing hardware, which is the foundational data point for energy calculation [4]. |

| Energy Estimation Coefficient | A research-derived multiplier. Since a GPU's energy draw doesn't account for the entire data center's consumption (cooling, CPUs, etc.), a common approximation is to double the GPU's energy use to estimate the total system energy [4]. |

| Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) Framework | A methodological "reagent" for accounting for both operational carbon (from electricity use) and embodied carbon (from manufacturing the hardware and constructing the data center) [1]. |

| Net Climate Impact Score | A framework developed by MIT collaborators to evaluate the net climate impact of AI projects, weighing emissions costs against potential environmental benefits [1]. |

| Open-Source AI Models | Models like Meta's Llama allow researchers to directly access, modify, and instrument the code for precise energy measurement, unlike "closed" models where energy data is a black box [4]. |

Experimental Protocol: Measuring and Reducing Model Training Energy

Objective: To quantify the energy consumption of a model training task and validate the energy savings achieved by implementing an early stopping policy.

Materials:

- Hardware: Server with one or more NVIDIA GPUs (e.g., H100, A100).

- Software: Python,

nvidia-smiCLI tool,pynvmllibrary, machine learning framework (e.g., PyTorch/TensorFlow). - Model & Dataset: A standard model (e.g., ResNet-50) and dataset (e.g., CIFAR-10) for benchmarking.

Methodology:

Baseline Energy Measurement:

- Initialize the GPU power monitoring tool at the start of the training job.

- Train the model to its maximum possible convergence or for a fixed, large number of epochs.

- Record the total energy consumed (in Joules) by querying the GPU's total energy consumption. Use the energy estimation coefficient to approximate the full system energy [4].

- Record the final validation accuracy.

Intervention with Early Stopping:

- Define a target validation accuracy that is 2-3% below the baseline's maximum accuracy [1].

- Configure the training script to monitor validation accuracy and stop training once the target is met for a set number of consecutive epochs.

- Repeat the training process with the identical setup, measuring the total energy consumed until the early stopping trigger.

Data Analysis:

- Calculate the energy saving: Energy Saved = Baseline Energy - Intervention Energy.

- Calculate the accuracy trade-off: Accuracy Difference = Baseline Accuracy - Intervention Accuracy.

- Report the results as the percentage of energy saved for the minor loss in accuracy.

The workflow for this protocol is shown below.

The environmental footprint of AI extends beyond its substantial electricity consumption to include significant water use for cooling and hardware-related impacts. The table below summarizes key quantitative metrics.

| Environmental Factor | Key Metric | Source / Context |

|---|---|---|

| Global Data Center Electricity Consumption | Expected to more than double, to around 945 TWh by 2030. [1] | Slightly more than the annual energy consumption of Japan. [1] |

| US Data Center Electricity Demand | Could account for 8.6% of total US electricity use by 2035. [6] | More than double the current share. [6] |

| AI Query Energy | A single ChatGPT query can use ~10 times more electricity than a simple Google search. [7] [8] | |

| Carbon Emissions | AI growth in the US could add 24 to 44 Mt CO₂-eq annually by 2030. [9] | Equivalent to adding 10 million gasoline cars to the road. [10] |

| Total Water Footprint (US AI Servers, 2024-2030) | Projected at 731 to 1,125 million m³ per year. [9] | Includes direct cooling and indirect power generation water use. [9] |

| Data Center Cooling Water Use | Can require ~2 liters of water for every kilowatt-hour of energy consumed. [7] | Used for heat rejection, potentially straining freshwater resources. [7] [8] |

| Electronic Waste | Driven by the short lifespan of high-performance computing hardware like GPUs. [11] | Contributes to the global e-waste crisis; manufacturing requires rare earth minerals. [11] [8] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the "Scope 1, 2, and 3" emissions for AI servers? The climate impact of AI servers is categorized into three scopes for accounting purposes. Scope 1 covers direct emissions from owned or controlled sources, such as diesel backup generators and water evaporation from on-site cooling towers [9]. Scope 2 accounts for indirect emissions from the generation of purchased electricity, which constitutes a substantial portion of the total footprint [9]. Scope 3 includes all other indirect emissions from the entire value chain, most notably from the manufacturing and end-of-life treatment of servers and computing hardware [9].

2. Beyond training, what other AI process is highly energy-intensive? The process of using a trained model to make predictions, known as inference, is becoming a dominant source of energy consumption [7]. As generative AI models are integrated into countless applications and used by millions of users daily, the aggregate electricity needed for inference can surpass that of the initial training phase [7]. Each query to a large model consumes significant energy.

3. What is the difference between PUE and WUE? PUE (Power Usage Effectiveness) is a metric that measures how efficiently a data center uses energy. It is calculated by dividing the total facility energy by the energy used solely by the IT equipment. A lower PUE (closer to 1.0) indicates higher efficiency [9]. WUE (Water Usage Effectiveness) measures the water efficiency of a data center, representing the liters of water used per kilowatt-hour of energy consumed. It includes both direct water use for cooling and the indirect water footprint of electricity generation [9].

4. How can my research team measure the carbon footprint of our AI models? Begin by profiling your model's computational requirements. Track the total GPU/CPU hours used for training and inference on your specific hardware [1]. Then, use the local grid's carbon intensity (in grams of CO₂-equivalent per kWh) for the region where your computations are performed to convert energy use into emissions [1]. Remember that emissions can vary significantly by time of day and location.

5. What are "embodied carbon" emissions in AI hardware? Embodied carbon refers to the greenhouse gas emissions generated from the manufacturing, transportation, and disposal of physical infrastructure, not from its operation [1]. For AI, this includes the carbon cost of producing GPUs, servers, and even constructing the data centers themselves. This is often overlooked in favor of operational carbon but represents a significant portion of the total lifecycle impact [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: High Water Footprint in Model Training

Problem: Your large-scale model training runs are contributing to a high water footprint due to data center cooling.

Diagnosis Methodology:

- Step 1: Identify Location: Determine the physical location of the data center or cloud region you are using (e.g., us-west1, eu-central1).

- Step 2: Assess Local Water Stress: Use tools like the WUI (Water Usage Effectiveness) and cross-reference with regional water stress maps to understand the local environmental impact [9].

- Step 3: Analyze Workload Timing: Review if training jobs are scheduled during peak ambient temperature hours, which typically increases cooling demands and water consumption [9].

Resolution Protocols:

- Leverage Cooler Climates: Where possible, select data center regions in cooler climates that can use air-side economizers (using outside air for cooling) for a larger portion of the year, drastically reducing water use [9].

- Adopt Advanced Cooling: Advocate for or select providers that use Advanced Liquid Cooling (ALC) systems, particularly immersion cooling, which can reduce the total water footprint by eliminating evaporative cooling needs [9].

- Optimize Scheduling: Schedule computationally intensive training workloads for cooler times of the day or night to minimize the energy required for cooling [1].

Issue 2: Managing the Carbon Footprint of AI Experiments

Problem: The carbon emissions from your frequent and long-running AI model experiments are high.

Diagnosis Methodology:

- Step 1: Calculate Operational Carbon: Use the formula:

Total GPU hours * GPU power draw (kW) * Grid Carbon Intensity (gCO₂e/kWh). Many cloud providers offer carbon footprint calculators. - Step 2: Profile Model Efficiency: Evaluate your model's architecture for inefficiencies. Tools can help profile the energy cost per inference or training step.

Resolution Protocols:

- Location and Time Flexibility: If your workload is flexible, run it in geographical regions with a high penetration of renewables (e.g., solar during the day, wind at night) and at times when grid carbon intensity is lowest [1].

- Model Efficiency Techniques:

- Pruning: Remove redundant parameters (weights) from the neural network.

- Quantization: Reduce the numerical precision of the model's calculations (e.g., from 32-bit to 16-bit or 8-bit). This can allow the use of less powerful, more efficient processors [1].

- Early Stopping: Halt the training process once performance plateaus, as the final percentage points of accuracy can consume a disproportionate amount of energy [1].

- Use Smaller, Domain-Specific Models: Instead of fine-tuning a massive general-purpose model, consider training a smaller, specialized model from scratch for your specific domain, which can be computationally cheaper [11].

Issue 3: Hardware Obsolescence and E-Waste

Problem: Rapid hardware upgrades and short lifespans of specialized AI accelerators (GPUs) are contributing to electronic waste.

Diagnosis Methodology:

- Step 1: Audit Hardware Lifecycle: Track the procurement and decommissioning dates of your compute hardware to understand its typical service life.

- Step 2: Evaluate Performance vs. Task: Determine if retired hardware is truly obsolete for all tasks, or if it is still viable for less computationally intensive workloads like smaller-scale inference or development.

Resolution Protocols:

- Lifecycle Extension: Instead of discarding, redeploy older GPUs for less demanding tasks such as prototyping, testing, or smaller inference jobs.

- Responsible Recycling and Resale: Partner with certified e-waste recyclers to ensure hazardous materials are handled properly. Explore resale markets for hardware that still has functional life.

- Prioritize Efficient Architectures: When procuring new hardware, prioritize energy efficiency (e.g., performance per watt) and vendors with strong environmental and take-back policies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Concepts & Metrics

| Tool / Concept | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Power Usage Effectiveness (PUE) | Measures data center infrastructure efficiency. A key metric for diagnosing energy waste. [9] |

| Water Usage Effectiveness (WUE) | Measures the liters of water used per kilowatt-hour of IT energy consumed, critical for assessing water impact. [9] |

| Carbon Intensity Data | Location-specific data (gCO₂e/kWh) essential for accurately calculating the carbon footprint of computational work. [1] |

| Model Pruning & Quantization | Techniques to create smaller, faster, and more energy-efficient models without significant loss of accuracy. [1] |

| Advanced Liquid Cooling (ALC) | A cooling technology that can significantly reduce both energy and water consumption compared to traditional air and evaporative cooling. [9] |

Experimental Protocol: System-Level Impact Assessment

Objective: To holistically assess the energy, water, and carbon footprint of a defined AI workload.

Workflow:

Methodology:

- Workload Profiling: Run the AI workload on a dedicated node and use profiling tools to measure the total energy consumed by the CPUs and GPUs in kilowatt-hours (kWh). Record the total computation time.

- Infrastructure Efficiency Factor: Obtain the Power Usage Effectiveness (PUE) for the data center housing the compute resources. If unavailable, use a standard estimate (e.g., 1.55). Multiply the IT energy consumption by the PUE to get the total facility energy consumption [9].

- Location-Based Impact Calculation:

- Carbon: Multiply the total facility energy by the grid carbon intensity (gCO₂e/kWh) for the region. This data can be sourced from regional grid operators or published datasets [1].

- Water: Multiply the total facility energy by the Water Usage Effectiveness (WUE) for the data center. If WUE is unknown, use a standard estimate (e.g., 1.8 L/kWh) or a location-specific factor that includes the water intensity of the local power grid [9].

- Synthesis and Reporting: Compile the results into a final report that presents the energy, water, and carbon costs of the workload, providing a multi-faceted view of its environmental impact.

System Optimization Pathways

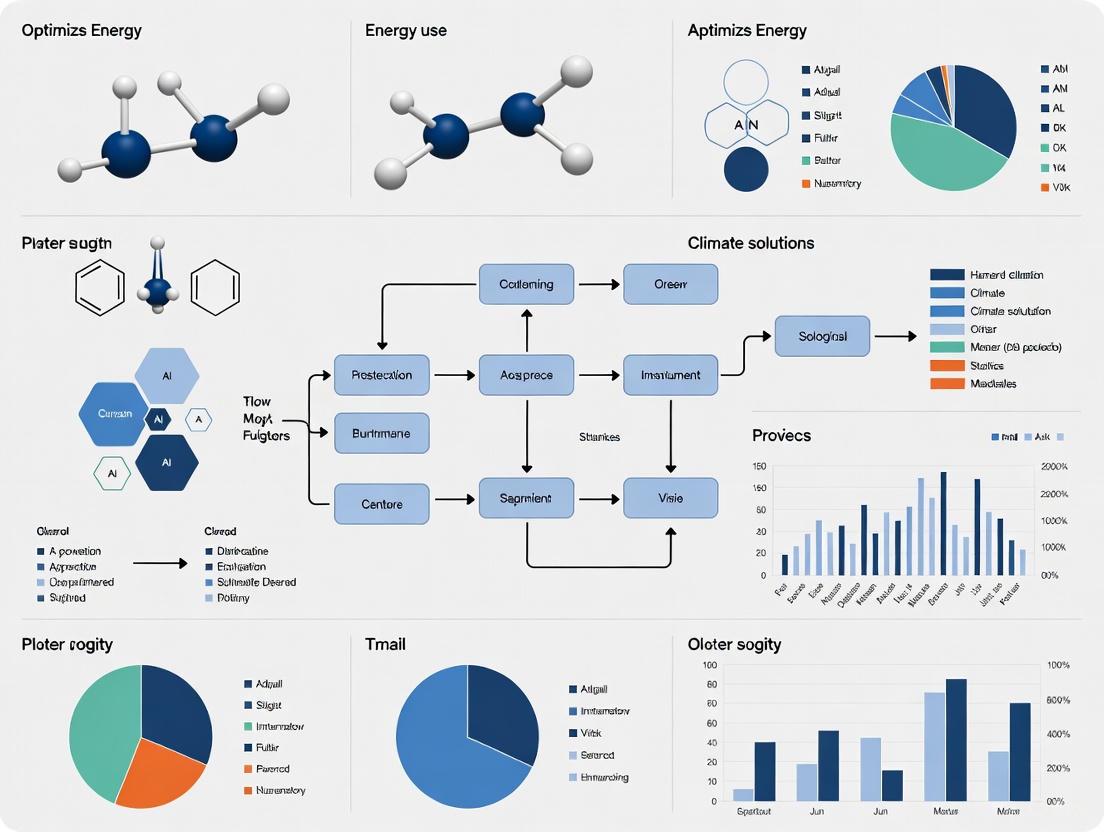

The following diagram illustrates the primary pathways and logical relationships for mitigating the environmental impact of AI computing, from hardware and algorithms to system-level planning.

FAQs: AI and Carbon Emissions

What is the projected energy demand growth from AI data centers? The International Energy Agency (IEA) predicts that global electricity demand from data centers will more than double by 2030, reaching approximately 945 terawatt-hours (TWh). This amount is slightly more than the total energy consumption of Japan [1]. Furthermore, energy demand from dedicated AI data centers is set to more than quadruple by 2030 [12].

How will this growth in AI impact carbon emissions? It is forecast that about 60% of the increasing electricity demands from data centers will be met by burning fossil fuels. This is projected to increase global carbon emissions by approximately 220 million tons per year [1]. For context, driving a gas-powered car for 5,000 miles produces about 1 ton of carbon dioxide [1]. Another projection estimates that by 2030, data centers may emit 2.5 billion tonnes of CO2 annually due to the AI boom, which is roughly 40% of the U.S.'s current annual emissions [12].

How does the carbon impact of training compare to using (inferencing with) AI models? While training large AI models is highly energy-intensive, the environmental impact from inference—the use of these models to make predictions or answer queries—is equally or more significant. This is because inference happens far more frequently than training. For popular models, it could take just a couple of weeks or months for usage emissions to exceed the emissions generated during the training phase [12].

What are the most carbon-intensive AI tasks? Generating images is by far the most energy- and carbon-intensive common AI-based task [12]. Research has found that a single AI-generated image can use as much energy as half a smartphone charge, though this varies significantly between models [12]. In contrast, generating text is generally less energy-intensive [12].

Are there differences in emissions between AI models and queries? Yes, there can be dramatic differences. One study noted that the least carbon-intensive text generation model produces 6,833 times less carbon than the most carbon-intensive image model [12]. Furthermore, the nature of a user's query matters; complex prompts that require logical reasoning (e.g., about philosophy) can lead to 50 times the carbon emissions of simple, well-defined questions [12].

Beyond carbon, what other environmental impacts does AI have? AI operations have a significant water footprint for cooling data centers. A short conversation of 20-50 questions with a large model like GPT-3 can cost an estimated half a liter of fresh water [12]. Training GPT-3 in Microsoft's U.S. data centers was estimated to directly evaporate 700,000 liters of clean fresh water [12]. E-waste from AI hardware is another growing concern, with one study projecting cumulative e-waste to reach 16 million tons by 2030 [12].

Troubleshooting Guide: Reducing Your AI Carbon Footprint

Problem: High Operational Carbon Emissions from Model Training and Inference

Solution: Implement a multi-layered strategy focusing on hardware, algorithms, and scheduling.

Action 1: Improve Hardware and Model Efficiency

- Reduce Precision: Switch to less powerful processors or lower-precision computing hardware that has been tuned for specific AI workloads. This can achieve similar results with lower energy consumption [1].

- Adopt Efficient Model Architectures: Favor algorithmic improvements that solve problems faster. Research indicates that efficiency gains from new model architectures are doubling every eight or nine months, creating "negaflops"—computing operations that no longer need to be performed [1].

- Avoid Unnecessary Training: Evaluate if you need the highest possible accuracy. About half the electricity for training a model can be spent to gain the last 2-3 percentage points in accuracy. For some applications, a lower accuracy may be sufficient and save substantial energy [1].

Action 2: Optimize Computational Workflow

- Stop Training Early: Use early stopping techniques to halt the training process once performance plateaus, avoiding wasted cycles on diminishing returns [1].

- Avoid Grid Search: For hyperparameter tuning, use random search instead of exhaustive grid search, as it is a significant source of unnecessary emissions [13].

- Eliminate Redundant Simulations: Build tools to identify and avoid redundant computing cycles, for example, by more efficiently selecting the best models during training [1].

Action 3: Leverage Temporal and Locational Carbon Awareness

- Schedule Flexibly: Split non-urgent computing operations to run later, when the local electricity grid has a higher proportion of power from renewable sources like solar and wind [1].

- Choose Cloud Region Wisely: If regulations allow, select a cloud region with a higher carbon efficiency (more renewable energy in its grid mix) [13]. The carbon intensity of electricity can vary significantly by region [14].

Problem: High Embodied Carbon from Computing Infrastructure

Solution: Acknowledge and mitigate the carbon cost of manufacturing hardware and building data centers.

- Action 1: Extend Hardware Lifespan

- Maximize the useful life of existing computing equipment to amortize its embodied carbon over a longer period.

- Action 2: Advocate for Sustainable Infrastructure

- Support companies and data center operators that are exploring more sustainable building materials and reporting on their embodied carbon [1].

Problem: Lack of Awareness and Measurement

Solution: Integrate carbon emission tracking into the research lifecycle and promote transparency.

- Action 1: Use a Carbon Calculator

- Utilize tools like the open-source CodeCarbon library to integrate carbon emission estimations directly into your Python workflow [13].

- Leverage carbon footprint calculators (e.g., from Deloitte) that score impact based on model, infrastructure, location, and use case to get actionable insights [14].

- Action 2: Report Emissions

- Include a dedicated section on carbon emissions in your publications, whether research papers or blog posts, to push for greater field-wide transparency [13].

Quantitative Data on AI's Environmental Impact

The following tables consolidate key statistics from recent analyses to provide a clear overview of AI's projected environmental footprint.

Table 1: Projected Energy and Carbon Emissions from AI Growth

| Metric | Projected Figure (by 2030) | Baseline Comparison |

|---|---|---|

| Global Data Center Electricity Demand | 945 TWh [1] | Slightly more than Japan's annual consumption [1] |

| Increase in Data Center Power Demand | Growth of 160% [12] | Driven by AI adoption |

| Annual Carbon Emissions from Data Centers | 2.5 billion tonnes of CO2 [12] | ~40% of current U.S. annual emissions [12] |

| Annual AI-specific Carbon Emissions (U.S. only) | 24-44 million metric tons of CO2 [12] | Emissions of 5-10 million more cars [12] |

Table 2: Carbon Impact of Specific AI Tasks and Models

| Task / Model | Carbon / Energy Equivalent | Context & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| AI-generated Image (most intensive model) | 4.1 miles driven by a car [12] | For 1,000 inferences |

| AI-generated Text (most efficient model) | 0.0006 miles driven by a car [12] | For 1,000 inferences; 6,833x less than worst image model |

| Training GPT-3 | 626,000 lbs of CO2 [12] | Equivalent to ~300 round-trip flights from NY to SF [12] |

| Single ChatGPT Query | 2.9 watt-hours [12] | Nearly 10x a single Google search (0.3 Wh) [12] |

Table 3: Water Consumption and E-Waste Projections

| Category | Estimated Consumption / Waste | Source / Context |

|---|---|---|

| Water per 20-50 Q&A Chat | 0.5 liters [12] | Conversation with ChatGPT (GPT-3) |

| Water for Training GPT-3 | 700,000 liters [12] | Enough to produce 320 Tesla EVs [12] |

| Cumulative AI E-waste by 2030 | 16 million tons [12] | Growing rapidly as a waste stream |

| U.S. Annual Water Use from AI by 2030 | 731-1,125 million m³ [12] | Annual water usage of 6-10 million Americans [12] |

Experimental Protocol: Measuring and Optimizing AI Carbon Footprint

Objective: To quantify the carbon dioxide emissions from training a machine learning model and identify optimization strategies for reduction.

Materials: The "Research Reagent Solutions" and essential materials for this experiment are listed in the table below.

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item Name | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| CodeCarbon Library | Open-source Python package that integrates with code to estimate hardware power consumption and calculate associated carbon emissions [13]. |

| Cloud Provider/GPU Selection | Different providers and regions have varying carbon efficiency. This is a key variable for choosing low-emission computing infrastructure [13]. |

| Model Architecture (e.g., Transformer, CNN) | The choice of model is a primary factor in computational efficiency. Newer, more efficient architectures can achieve the same result with fewer "negaflops" [1]. |

| Hyperparameter Set (Random vs. Grid) | The strategy for tuning model parameters significantly impacts the number of runs required. Random search is preferred over grid search to reduce emissions [13]. |

| Early Stopping Callback | A programming function that halts model training when performance on a validation set stops improving, preventing wasteful computation [1]. |

Methodology:

- Baseline Measurement:

- Initialize the CodeCarbon tracker in your training script [13].

- Train your model on a reference dataset (e.g., CIFAR-10, IMDB) using a standard architecture (e.g., ResNet-50, BERT-base) and a standard cloud region.

- Record the total emissions in grams of CO2 equivalent (gCO2eq), the energy consumed (kWh), and the training time.

Intervention 1 - Locational Optimization:

Intervention 2 - Algorithmic Optimization:

- Repeat the training process using a more efficient model architecture (e.g., a distilled version of the original model or a recently published efficient architecture) [1].

- Compare the emissions, energy, and time to the baseline.

Intervention 3 - Process Optimization:

- Repeat the training process using a random search for hyperparameter tuning instead of a full grid search [13].

- Implement an early stopping callback with a patience parameter of 3 epochs.

- Compare the total number of training runs and final emissions.

Analysis:

- Calculate the percentage reduction in emissions for each intervention compared to the baseline.

- Analyze the trade-offs, if any, between model accuracy/performance and emission reduction.

- Determine the most effective single intervention and whether combinations of interventions have a multiplicative effect.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for a carbon-aware AI experiment, integrating measurement and mitigation strategies from the troubleshooting guide and experimental protocol.

Carbon Aware AI Research Workflow

Technical Support Center: Optimizing Energy Use in AI-Powered Climate Research

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: High Computational Energy Consumption During Model Training

- Problem: Training complex climate models (e.g., for weather prediction or emissions monitoring) consumes excessive energy, leading to high operational costs and a large carbon footprint [1].

- Diagnosis: This is often caused by using very large, general-purpose models or pursuing marginal gains in accuracy that require disproportionately more energy [15] [1].

- Solution:

- Employ Early Stopping: Analyze your model's learning curve. If accuracy plateaus, halting the training process early can save significant energy with a negligible impact on performance [1].

- Use a Domain-Specific Model: Instead of retraining a massive foundation model, fine-tune a smaller, pre-existing model specifically for your climate science task (e.g., analyzing satellite imagery for deforestation). This reduces computational overhead [11].

- Simplify the Model: For your specific task, a model with fewer parameters might be sufficient. Experiment with model compression or knowledge distillation techniques to create a more efficient version [15].

Issue 2: Slow or Inefficient Model Inference

- Problem: Running a deployed model for climate analysis (e.g., predicting flood zones) is slow, energy-intensive, and costly at scale [15].

- Diagnosis: The model might be overly complex for the inference task, or it might be running on inefficient hardware [15].

- Solution:

- Reduce Precision: Switch the model's numerical precision from 32-bit floating-point (FP32) to 16-bit (FP16) or even 8-bit integers (INT8) during inference. This can drastically reduce energy use and increase speed with minimal accuracy loss [1].

- Optimize Hardware Selection: Deploy your model on hardware accelerators like Tensor Processing Units (TPUs) or neuromorphic chips that are specifically designed for efficient AI inference, rather than general-purpose GPUs [11].

Issue 3: Unclear Carbon Footprint of AI Workflows

- Problem: You cannot quantify or report the environmental impact of your AI research projects [15].

- Diagnosis: Lack of integration of carbon footprint tracking tools into the machine learning lifecycle [15].

- Solution:

- Integrate Measurement Tools: Use open-source libraries like CodeCarbon to automatically track energy consumption and estimate carbon emissions during model training and experimentation. This data is crucial for making informed, sustainable choices [15].

Issue 4: Data Center Energy Mix is Carbon-Intensive

- Problem: Even an efficient model run in a data center powered by fossil fuels will have a high carbon footprint [1].

- Diagnosis: The computing workload is not aligned with the availability of renewable energy on the grid [1].

- Solution:

- Leverage Temporal and Spatial Flexibility: Schedule large, non-urgent training jobs for times when grid carbon intensity is low (e.g., during peak solar or wind generation). If possible, select cloud regions with a higher percentage of renewable energy sources [1].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the single most effective way to reduce the energy footprint of my AI climate model? A1: Focusing on algorithmic efficiency is the most impactful strategy. A more efficient model architecture that solves problems faster and with less computation is the key to reducing environmental costs. Research indicates that efficiency gains from new model architectures are doubling every eight to nine months [1].

Q2: Should I be more concerned about the energy used for training a model or for using it (inference)? A2: For models deployed at scale, the inference phase often accounts for the majority of the energy consumption. While training a single model is highly energy-intensive, the cumulative energy used for billions of user queries and predictions in a deployed model far exceeds the initial training cost [15].

Q3: How can I choose a more energy-efficient AI model from the start? A3: Prioritize model architectures known for efficiency and match the model's size and complexity to your specific task. Using a massive, trillion-parameter model for a simple classification task is inefficient. Refer to research on model efficiency and benchmark different architectures on your task before full-scale training [15] [11].

Q4: Our climate model requires high precision. How can we still be energy-efficient? A4: High precision and efficiency are not always mutually exclusive. You can adopt a multi-fidelity approach: use a simpler, faster model for initial exploration and preliminary results, and reserve the high-precision, energy-intensive model only for the final, critical simulations. Furthermore, techniques like pruning can remove unnecessary components from a neural network, maintaining accuracy while reducing computational load [1].

Quantitative Data on AI Model Efficiency

The table below summarizes the growth in model size and the associated increase in computational demands. This highlights the critical need for the optimization strategies discussed in this guide.

| Model Name | Parameter Count | Relative Energy Demand & Trends |

|---|---|---|

| GPT-1 [15] | 114 Million | Lower computational footprint, suitable for smaller-scale tasks. |

| GPT-2 [15] | 1.5 Billion | Increased energy requirement for training and inference. |

| GPT-3 [15] | 175 Billion | High energy consumption, highlighting the trend of growing model size. |

| Llama 3.1 (Largest) [15] | 405 Billion | Very high energy demand, necessitating advanced efficiency techniques. |

| Key Trend | Model sizes are growing exponentially. | This leads to higher accuracy but also significantly increased energy consumption during both training and inference, raising environmental concerns [15]. |

Experimental Protocol: Measuring Carbon Footprint with CodeCarbon

Objective: To quantitatively measure and compare the carbon dioxide emissions from training machine learning models of varying complexity.

Methodology:

- Tool Installation: Install the

codecarbonPython package using the commandpip install codecarbon[15]. - Experiment Setup: Define multiple training scenarios with increasing computational load. Variables can include dataset size (

n_samples), model complexity (n_estimators,max_depth), and model type [15]. - Emissions Tracking:

- Data Collection: The tracker will log energy consumption and convert it into an estimated CO₂ equivalent, which is saved to an

emissions.csvfile for analysis [15]. - Analysis: Compare the emissions (in kg of CO₂eq) and emissions per sample across the different experimental scenarios to understand the cost of model complexity [15].

AI for Climate Research: Energy Optimization Workflow

The diagram below outlines a systematic workflow for developing energy-efficient AI models in climate research.

Research Reagent Solutions: The Energy-Efficient AI Toolkit

This table details key digital "reagents" – software tools and strategies – essential for building sustainable AI solutions for climate research.

| Tool / Strategy | Function in Sustainable AI Research |

|---|---|

| CodeCarbon [15] | An open-source library that integrates with your code to directly measure and track the energy consumption and carbon emissions of your model training experiments. |

| Efficient Model Architectures (e.g., compressed models, Mixture of Experts) [15] | Designed to achieve high performance with fewer computational operations, directly reducing the energy required for both training and inference. |

| Low-Precision Computing (FP16, INT8) [1] | A hardware/software strategy that reduces the numerical precision of calculations, significantly speeding up processing and lowering energy use with minimal accuracy loss. |

| Temporal Scheduling [1] | An operational strategy that involves scheduling compute-intensive training jobs for times when the local power grid has a higher mix of renewable energy, reducing the carbon footprint. |

| Hardware Accelerators (TPUs, Neuromorphic Chips) [11] | Specialized processors that are architecturally optimized for executing AI workloads much more efficiently than general-purpose CPUs and GPUs. |

AI in Action: Methodologies for Climate Modeling and Energy Optimization

High-Resolution Climate and Weather Prediction with AI Models

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Systematic Cold Biases in Model Outputs

Problem: My AI model's predicted surface temperatures are consistently colder than observed, particularly for extreme heat events.

Explanation: This is a known challenge where AI models trained predominantly on historical data learn a climate state that is outdated. The model's predictions may resemble a climate from 15-30 years prior to the target period, a phenomenon documented in several prominent AI weather and climate models [16].

Solution Steps:

- Diagnose the Bias: Compare your model's output over a validation period against the latest reanalysis data (e.g., ERA5). Quantify the bias specifically for extreme temperature percentiles (e.g., the 95th percentile) and for regions experiencing rapid warming [16].

- Incorporate Up-to-Date Training Data: Ensure your training dataset includes the most recent years of data to expose the model to modern climate extremes. If using a pre-trained model, check its training period [16].

- Integrate External Climate Forcings: For climate-scale predictions, use models that explicitly include forcing data, such as CO₂ concentrations, to help the model represent the current climate state better [16].

- Apply Hybrid Modeling: Combine your AI model with a traditional Numerical Weather Prediction (NWP) model. The physics-based NWP model can provide a stronger anchor to contemporary atmospheric states, while the AI component enhances speed and efficiency [17] [18].

Guide 2: Managing the High Computational Demand of AI Models

Problem: Training and running high-resolution AI models requires excessive computational resources and energy.

Explanation: While AI inference can be vastly more efficient than running traditional NWP models, the training phase and complex architectures (e.g., deep learning models with billions of parameters) can be computationally intensive [17] [19].

Solution Steps:

- Leverage Pre-trained Models: Use foundational AI weather models (e.g., ECMWF's AIFS, FourCastNet, Pangu-Weather) as a starting point for your specific task. Fine-tuning a pre-trained model is significantly less resource-intensive than training from scratch [19] [20].

- Optimize Model Architecture: Explore more efficient architectures like Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), which are used in models like GraphCast and WeatherNext for their computational efficiency [20].

- Implement Power-Flexible Computing: Investigate computing frameworks designed for energy efficiency, such as those that can modulate power usage during times of peak grid demand. This aligns AI compute with sustainable energy practices [21].

Guide 3: Improving Physical Consistency in AI-Generated Forecasts

Problem: The AI model produces meteorologically implausible states or fails to respect known physical laws.

Explanation: Pure data-driven AI models learn patterns from historical data but do not inherently incorporate physical laws like conservation of energy and mass. This can sometimes lead to unrealistic forecasts, especially for longer lead times [17].

Solution Steps:

- Employ Hybrid AI-NWP Systems: Integrate AI components within a traditional dynamical model framework. For example, use a machine learning algorithm to learn and correct the systematic errors of an NWP model, creating a hybrid system that benefits from both data-driven learning and physical constraints [17] [18].

- Use Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs): Incorporate physical governing equations directly into the model's loss function during training to penalize physically unrealistic outputs.

- Apply Post-hoc Physical Constraints: Develop and apply filters or correction algorithms to the model's output to ensure it adheres to fundamental physical principles.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the primary energy efficiency advantages of using AI for weather forecasting compared to traditional NWP?

AI models offer a dramatic reduction in energy consumption for generating forecasts. Once trained, an AI model can produce a forecast thousands of times faster and using about 1,000 times less energy than running a conventional physics-based NWP model [19]. This makes frequent, high-resolution forecast updates computationally feasible and more sustainable [21] [22].

FAQ 2: My AI model performs well on average conditions but fails on extreme weather events. Why?

Extreme events are, by definition, rare in the historical record, leading to a small sample size for the model to learn from. Furthermore, if the model was trained on data from a cooler historical period, it may have never encountered the intensity of modern extreme heat events, causing a systematic cold bias during heatwaves [16]. Specialized techniques, like ensemble forecasting with AI models and training on carefully curated datasets enriched with extreme event examples, are required to improve performance in these high-impact scenarios [23].

FAQ 3: What is the "black box" problem in AI weather forecasting, and how can I mitigate it?

The "black box" problem refers to the difficulty in understanding how a complex AI model (like a deep neural network) arrives at a specific forecast. This can be a barrier to trust for meteorologists [17]. Mitigation strategies include:

- Using Explainable AI (XAI) techniques: Apply methods like SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) to identify which input variables were most influential for a given prediction [23].

- Developing interpretable architectures: Some newer models are designed with interpretability in mind, using components like prototype layers to make the decision-making process more transparent [23].

- Rigorous verification and validation: Consistently benchmark your model's outputs against observations and other models to build confidence in its reliability over time.

FAQ 4: Should I use a pure AI model or a hybrid AI-NWP system for my research?

The choice depends on your application's requirements for speed, accuracy, and physical consistency.

- Pure AI Models: Best for applications requiring the fastest possible forecast generation and high energy efficiency, and where some physical inconsistencies may be acceptable for the specific use case (e.g., certain energy trading decisions) [22].

- Hybrid AI-NWP Systems: Recommended for applications where physical realism and robust performance across diverse weather phenomena are critical. Hybrid models combine the pattern-recognition strength of AI with the physical fidelity of NWP, often leading to superior overall accuracy and reliability [17] [19] [18]. They are particularly valuable for predicting complex extreme events.

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Implementing an ML-Based Dynamical Model Error Correction

This protocol outlines the methodology for using machine learning to correct systematic errors in a dynamical climate model, forming a hybrid model for improved prediction [18].

Methodology:

- Generate Analysis Increments: Run a Data Assimilation (DA) system that combines model forecasts (background) with observations to produce a best estimate of the current state (analysis). The differences between the analysis and the background fields are the "analysis increments," which represent the model's systematic errors [18].

- Train the ML Error Model: Use the historical record of the dynamical model's states and the corresponding analysis increments as training data. Train a machine learning model (e.g., a neural network) to predict the analysis increments given the model's state. This ML model learns to emulate the model error [18].

- Integrate into Hybrid Model: During the prediction phase, at each time step, use the trained ML model to calculate the error correction based on the current model state. Apply this correction to the dynamical model's tendencies before numerical integration [18].

- Validation: Compare the long-term prediction skill of the hybrid model against the standalone dynamical model for key atmospheric and oceanic variables.

The workflow for this error correction method is as follows:

Protocol 2: AI-Driven Detection and Localization of Extreme Weather Events

This protocol describes a process for detecting and localizing extreme weather events (e.g., floods, heatwaves) using AI computer vision techniques on climate and satellite data [23].

Methodology:

- Data Preparation & Labeling: Compile a multi-source dataset including reanalysis data (e.g., ERA5 variables like temperature, pressure) and satellite remote sensing imagery. Use expert knowledge or existing databases to create labels for the occurrence and spatial extent of target extreme events [23].

- Model Training: Frame the problem as an image segmentation or object detection task. Train a deep learning model, such as a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) or a U-Net architecture, on the prepared dataset. The model learns to identify the "fingerprint" of the extreme event in the input data [23].

- Model Evaluation & Explainability: Validate the model's detection performance against held-out data using metrics like Intersection-over-Union (IoU). Apply Explainable AI (XAI) techniques, such as Grad-CAM, to generate heatmaps highlighting the features in the input data that were most important for the detection, aiding scientific interpretation and trust [23].

- Deployment: Integrate the trained model into a processing pipeline for new, near-real-time data to provide automated monitoring and early alerts for extreme events.

The workflow for extreme event detection is as follows:

The table below summarizes key quantitative findings on the performance and efficiency of AI weather and climate models.

Table 1: AI Model Performance and Efficiency Metrics

| Model / System | Key Performance Metric | Energy & Speed Advantage | Key Limitation / Bias |

|---|---|---|---|

| ECMWF AIFS [19] | ~20% better tropical cyclone track prediction; outperforms IFS on many measures. | ~1000x less energy per forecast; generates forecast in minutes vs. hours. | Operational ensemble (AIFS Ensemble) still in development. |

| Climavision Horizon AI S2S [17] | 30% more accurate globally; 100% more accurate for specific locations vs. ECMWF. | Not explicitly quantified, but leverages AI's inherent computational speed. | Requires careful design to avoid the "black box" problem. |

| FourCastNet & Pangu [16] | State-of-the-art performance on standard weather benchmarks. | Significantly less computationally expensive than dynamical models. | Exhibits a cold bias, resembling a climate 15-20 years older than prediction period. |

| AI vs. Traditional NWP [21] | N/A | Energy efficiency for AI inference has improved 100,000x in the past 10 years. | N/A |

| Industry-wide Potential [21] | N/A | Full adoption could save ~4.5% of projected energy demand across industry, transportation, and buildings by 2035. | N/A |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Models

Table 2: Key Models and Data Sources for AI-Powered Climate Research

| Item | Function & Application | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| ERA5 Reanalysis | A foundational, high-quality global dataset of the historical climate used for training and validating most AI weather and climate models. | [16] |

| ECMWF AIFS | The first fully operational, open AI weather forecasting model from a major prediction center. A key benchmark and potential base model for research. | [19] |

| Pangu-Weather (Huawei) | A leading AI weather model based on a transformer architecture, trained on ERA5 data. Known for its high forecast accuracy. | [16] |

| FourCastNet (NVIDIA) | A high-resolution AI weather model using a Spherical Fourier Neural Operator (SFNO), effective for global forecasting. | [16] |

| GraphCast / WeatherNext (Google) | AI weather models based on Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), renowned for their computational efficiency and accuracy. | [20] |

| Explainable AI (XAI) Tools (e.g., SHAP, Grad-CAM) | Post-hoc analysis tools that help interpret the predictions of complex "black box" AI models by identifying influential input features. | [23] |

| Hybrid Model Framework | A software paradigm that integrates a data-driven ML model with a physics-based dynamical model to correct errors and improve prediction. | [18] |

Troubleshooting Guides

Common System Errors & Solutions

| Error Code / Symptom | Likely Cause | Immediate Action | Root Cause Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grid Stability Alert / Voltage fluctuations during high AI load | Simultaneous high demand from AI compute tasks and carbon capture system startup [24] [6] | 1. Reroute non-essential lab power.2. Initiate staggered startup for carbon capture units. | Install AI-driven predictive load balancer to forecast and manage energy spikes [25]. |

| CCS-101 / Drop in CO₂ capture efficiency (>15%) | Contamination of molten sorbent (lithium-sodium ortho-borate) or deviation from optimal temperature range [26] | 1. Perform sorbent purity test.2. Recalibrate and verify reactor core temperature sensors. | Integrate real-time sorbent composition analyzer with automated purification loop [26]. |

| AI-ML-308 / Model prediction accuracy degrades for renewable energy forecasts | Poor quality or incomplete historical weather/turbine performance data [25] | 1. Run data integrity checks on input datasets.2. Switch to backup data source. | Implement automated data validation pipeline with outlier detection and imputation [25]. |

| DAC-207 / Direct Air Capture system energy consumption exceeds projections | Clogged particulate filters increasing fan motor load, or suboptimal adsorption/desorption cycle timing [27] | 1. Inspect and replace intake filters.2. Review cycle pressure sensor logs. | Deploy computer vision system to monitor filter condition and AI to optimize cycle timing [25] [27]. |

Energy & Grid Management

Q: Our AI research workloads are causing significant energy cost spikes and grid instability. What are the immediate and long-term solutions?

A: This is a common challenge. Immediate actions include load shifting (scheduling non-urgent AI training during off-peak hours) and power capping (setting limits on GPU power draw). For a long-term solution, consider co-locating with renewable energy sources and integrating battery storage systems (BESS). A 1GW storage project, like the one by ZEN Energy, demonstrates how storage can stabilize the grid for energy-intensive research [25]. Furthermore, AI can itself be used to forecast energy demand and optimize your own facility's consumption [6].

Q: How can we validate the true carbon footprint of our AI-powered climate research to ensure net-positive impact?

A: Develop a detailed life-cycle assessment (LCA) model that accounts for:

- Embodied Carbon: From manufacturing computing hardware.

- Operational Carbon: Based on the energy source powering your data centers (ensure use of power purchase agreements (PPAs) for renewables [6]).

- Avoided Emissions: Quantify the CO₂ reductions enabled by your research outputs (e.g., optimized carbon capture). Platforms like Insight Terra's AI-driven GHG management tool can assist in this tracking [25].

Carbon Capture & Sequestration

Q: We are experiencing rapid degradation of our solid sorbent in high-temperature carbon capture experiments. How can we improve material stability?

A: Solid sorbents often fail at industrial furnace temperatures. A proven alternative is switching to a molten sorbent system. Research from MIT led to the discovery of lithium-sodium ortho-borate molten salt, which showed no degradation after over 1,000 absorption/desorption cycles at high temperatures. The liquid phase avoids the brittle cracking that plagues solid materials [26].

Q: What is the most energy-efficient method for providing the heat required for solvent regeneration in a capture system?

A: The primary energy cost is thermal energy for regeneration. The Mantel capture system addresses this by integrating the capture process with the heat source. Their design captures CO₂ and uses the subsequent temperature increase to generate steam, delivering that steam back to the industrial customer. This approach can reportedly require only 3% of the net energy of state-of-the-art capture systems, turning a cost center into a potential revenue stream [26].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Methodology: Testing Molten Sorbent for High-Temperature CCS

Objective: To evaluate the CO₂ absorption capacity, cycling stability, and kinetics of a lithium-sodium ortho-borate molten sorbent under conditions relevant to industrial flue gases [26].

Procedure:

- Sorbent Preparation: Inside an argon-filled glovebox, prepare 100g of anhydrous lithium-sodium ortho-borate salt mixture. Load into a high-temperature, corrosion-resistant alloy reactor.

- System Pre-conditioning: Seal the reactor and heat to the target operating temperature (e.g., 600–800°C) under a constant N₂ purge. Maintain for 1 hour.

- Absorption Cycle: Introduce a simulated flue gas mixture (15% CO₂, 85% N₂) at a fixed flow rate. Monitor and record the mass gain and CO₂ concentration in the outlet gas stream using a mass spectrometer until saturation is achieved.

- Desorption Cycle: Switch the gas flow back to 100% N₂ and increase the temperature by 50–100°C. Hold until the mass returns to baseline and the CO₂ concentration in the outlet falls to zero.

- Cycling Stability Test: Repeat steps 3 and 4 for a minimum of 50 cycles, measuring the absorption capacity at each cycle to track performance degradation [26].

Quantitative Performance Data

| Technology / Method | Typical CO₂ Capture Rate | Energy Penalty (vs. Baseline) | Key Limitation / Challenge | Commercial Scale Projection |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molten Salt Sorbent (Mantel) [26] | >95% | ~3% net energy use | Material corrosion at scale; high-purity CO₂ transport | Pilot plant with Kruger Inc. (2026); scaling to 100s of plants |

| Traditional Amine-Based CCS [27] | 85-90% | 20-30% energy use | Solvent degradation; high heat requirement for regeneration | Mature technology; deployed at several large-scale sites |

| Direct Air Capture (DAC) [27] | N/A (captures from air) | Very High (>500 kWh/tonne) | Extreme energy and cost intensity; land use | World's largest facility (STRATOS) operational; 0.5% of global emissions by 2030 [27] |

| AI-Optimized Renewable Grid [25] | N/A | Negative (improves efficiency) | Requires massive, high-quality datasets | 1GW storage projects underway; key to managing AI demand [25] [6] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Essential Material / Tool | Primary Function in Optimization Research |

|---|---|

| Lithium-Sodium Ortho-Borate Molten Salt | High-temperature CO₂ sorbent with exceptional cycling stability, avoiding solid-phase degradation [26]. |

| AI-Driven Digital Twin Platform | A virtual model of a physical system (e.g., a forest or power grid) used to simulate interventions and predict outcomes under different scenarios without real-world risk [25]. |

| High-Temperature Alloy Reactor Vessels | Contains corrosive molten salts at extreme temperatures (600–800°C) during carbon capture experiments [26]. |

| Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESS) | Provides short-duration energy storage to buffer intermittent renewable sources, crucial for powering steady AI computations and sensitive capture equipment [24]. |

System Workflow Diagrams

AI-Optimized Carbon Capture & Grid Integration

AI-Optimized Carbon Capture & Grid Integration Workflow

AI for Climate Tech Research Data Flow

AI for Climate Tech Research Data Flow

Accelerating Material Discovery for Climate Technologies

Technical Troubleshooting Guides

This section provides targeted solutions for common technical challenges encountered in AI-driven materials research, with a focus on optimizing computational efficiency and energy use.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Computational and Experimental Workflows

| Problem Category | Specific Issue | Possible Cause | Solution | Energy Optimization Link |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Modeling | Model training is slow and energy-intensive. | Overly complex model architecture; training for marginal accuracy gains. | Simplify the model architecture and employ "early stopping" once performance plateaus, as the last 2-3% of accuracy can consume half the electricity [1]. | Reduces direct operational energy consumption. |

| High energy footprint of computations. | Computations are run on standard, power-hungry hardware and/or at times of high grid carbon intensity. | Switch to less powerful, specialized processors tuned for specific tasks. Schedule intensive training for times when grid renewable energy supply is high [1]. | Leverages efficient hardware and cleaner energy sources, reducing operational carbon. | |

| Data Management | Difficulty in identifying relevant materials data. | Unstructured or non-standardized data sources; inefficient keyword searches. | Use AI tools to generate synonyms and domain-specific terminology to improve database search efficacy [28]. | Saves energy by reducing futile computational search time. |

| AI Workflow | High operational carbon from AI processing. | Use of powerful, general-purpose models for tasks that smaller models could handle. | Leverage algorithmic improvements. Use "model distillation" to create smaller, more energy-conscious models that achieve similar results [29]. | "Negaflops" from efficient algorithms avoid unnecessary computations, directly cutting energy use [1]. |

| Hardware & Infrastructure | High cooling demands for computing hardware. | Hardware running at full power continuously. | "Underclock" GPUs to consume about a third of the energy, which also reduces cooling load and has minimal impact on performance for many tasks [1]. | Reduces both the energy used for computation and for cooling. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key investment trends in materials discovery for climate tech? Investment is growing steadily, driven by equity financing and grants. The focus is on applications, computational materials science, and materials databases. The United States dominates global investment, with Europe, particularly the United Kingdom, also showing consistent activity [30].

Table 2: Materials Discovery Investment Trends (2020-2025)

| Year | Equity Investment (USD) | Grant Funding (USD) | Key Investor Types |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | $56 Million | Not Specified | Venture Capitalists |

| 2023 | Not Specified | $59.47 Million | Government, Corporate Investors |

| 2024 | Not Specified | $149.87 Million | Government (e.g., U.S. DoE), Corporate Investors |

| Mid-2025 | $206 Million | Not Specified | Venture Capitalists, Corporate Investors |

Source: Adapted from NetZero Insights analysis [30].

Q2: Which specific climate technologies can advanced materials and AI enable? A 2025 report from the World Economic Forum and Frontiers highlights ten emerging technologies with significant transformative potential. Several rely on advanced materials and AI [31] [32]:

- Soil Health Technology Convergence: Integrates in-field sensors, microbiome engineering, and AI to boost soil resilience and carbon storage.

- Green Concrete: Uses novel, cement-free binders that can permanently sequester CO₂ during curing.

- Timely and Specific Earth Observation: Combines satellite data and machine learning for real-time, high-resolution monitoring of climate and biodiversity.

Q3: How can I reduce the carbon footprint of my AI-driven research? A multi-pronged approach is most effective [29] [1]:

- Improve Algorithmic Efficiency: This is the most impactful step. Use model pruning, compression, and other techniques to achieve the same results with less computation.

- Optimize Hardware Usage: Select appropriate processor types and utilize hardware at reduced power settings where possible.

- Leverage a Greener Grid: Schedule energy-intensive tasks for times when local grid power comes from renewable sources.

- Consider Embodied Carbon: Account for the emissions from manufacturing computing hardware, not just the operational emissions.

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol for a High-Throughput Computational Screening Workflow

Objective: To efficiently identify promising novel inorganic materials for specific climate technology applications (e.g., battery cathodes, photovoltaic absorbers) using computational modeling.

Detailed Methodology:

- Define Target Properties: Establish the key material properties required for the application (e.g., band gap, thermodynamic stability, ionic conductivity).

- Select a Materials Database: Choose a high-quality database (e.g., the Materials Project, AFLOW) or create a curated list of candidate structures.

- Generate a Computational Workflow:

- Use high-throughput density functional theory (DFT) or other computational methods to calculate the target properties for each candidate material.

- Implement an AI-Powered Filter:

- Train a machine learning model on a subset of the DFT data to predict material properties, accelerating the screening of the remaining candidates.

- Validate and Analyze: Select the top-performing candidates from the screening for more detailed, higher-fidelity calculations and experimental validation.

The following diagram illustrates the information flow and decision points in this high-throughput screening workflow.

Protocol for an AI-Optimized Experimental Synthesis Loop

Objective: To accelerate the synthesis and testing of candidate materials by using AI to guide experimental parameters.

Detailed Methodology:

- Initial Design of Experiments (DoE): Define the experimental parameter space (e.g., temperature, pressure, precursor ratios).

- Parallel Synthesis: Use automated or self-driving labs to synthesize materials based on an initial set of conditions.

- High-Throughput Characterization: Automatically characterize the synthesized materials for key properties.

- AI Data Analysis and Proposal:

- Feed the synthesis parameters and resulting material properties into an AI/ML model.

- The model analyzes the data to propose the next, most informative set of synthesis conditions to test.

- Iterate: Repeat steps 2-4 in a closed loop, allowing the AI to efficiently navigate the parameter space towards the optimal material.

The following diagram maps the iterative, closed-loop process of AI-guided material synthesis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for AI-Accelerated Material Discovery

| Item / Solution | Function / Description | Relevance to Climate Tech |

|---|---|---|

| High-Quality Materials Databases | Structured repositories of material properties (e.g., crystal structures, band gaps) essential for training predictive AI models [30]. | Provides the foundational data for discovering materials for batteries, catalysts, and carbon capture. |

| Advanced Computational Modeling Platforms | Software for simulating material properties (e.g., using Density Functional Theory) before physical synthesis [30]. | Drastically reduces the time and resource cost of R&D by screening out non-viable candidates computationally. |

| Self-Driving Labs | Automated laboratories that use AI and robotics to perform high-throughput synthesis and characterization with minimal human intervention [30]. | Accelerates the experimental validation cycle, crucial for rapidly scaling new climate technologies. |

| AI for Earth Observation | AI-powered analytics that synthesize satellite, drone, and ground-based data for near real-time environmental monitoring [31] [32]. | Enables tracking of deforestation, methane leaks, and climate impacts, providing critical data for policy and intervention. |

Welcome to the Technical Support Center

This support center provides researchers and scientists with practical guidance for implementing AI-enhanced satellite analytics in climate and energy research. The following FAQs and troubleshooting guides address common technical challenges, helping you optimize your experiments and ensure compliance with evolving regulatory frameworks.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the most common causes of poor AI model performance when analyzing satellite imagery for environmental monitoring?

- A: Performance degradation often stems from three primary areas:

- Data Quality Issues: This includes misaligned data temporal resolution (e.g., daily satellite images paired with hourly weather data), inconsistent spatial resolution from different sensors, or uncalibrated sensor data leading to drift.

- Model Training Deficiencies: Insufficient training data for rare events (e.g., specific types of oil spills), incorrectly labeled training data, or model architecture that is not suited for the spatial-temporal nature of geospatial data.

- Operational Drift: The phenomenon where a model's performance decreases over time because the real-world environmental conditions it monitors have changed from the conditions in its training data.

FAQ 2: How can we ensure our AI-driven monitoring system complies with regulations like the EU AI Act?

- A: For systems used in official compliance and enforcement, which are likely classified as high-risk under the EU AI Act, you must implement several key measures [33]:

- Robust Governance: Establish a comprehensive AI governance framework with clear roles, responsibilities, and documentation practices [34].

- Risk Assessments: Conduct and document regular risk assessments focused on potential algorithmic bias, data privacy, and model inaccuracies [34] [33].

- Transparency and Documentation: Maintain detailed documentation of your AI systems, including data sources, model methodologies, and decision-making processes, for audits and regulators [34].

- Human Oversight: Ensure that critical decisions, especially those leading to enforcement actions, involve meaningful human review and are not fully automated [33].

FAQ 3: Our satellite data pipeline is experiencing significant latency, affecting near-real-time applications like wildfire detection. What steps can we take?

- A: Latency can be addressed by optimizing each stage of your data pipeline:

- Data Acquisition: Leverage edge computing. As demonstrated by systems using NVIDIA Jetson technology on CubeSats, performing initial AI inference (e.g., fire detection) onboard the satellite can reduce data downlink requirements and provide alerts within 60 seconds [35].

- Data Processing: Utilize high-performance computing frameworks and vector databases (e.g., Pinecone) to accelerate data retrieval and model inference times [36].

- Model Efficiency: Explore model quantization and the use of simpler, optimized neural architectures like Fourier Neural Operators that can maintain accuracy while reducing computational costs [35].

FAQ 4: We've observed potential algorithmic bias in our model that assesses permit compliance from satellite imagery. How can we diagnose and mitigate this?

- A: Bias can arise if training data is not representative of all geographic or demographic areas. Mitigation requires a multi-faceted approach:

- Diagnosis: Implement continuous monitoring and testing protocols. Use tools like Accessibility Scanner or custom scripts to check for disparate outcomes across different regions or community datasets [34] [37].

- Data Remediation: Audit your training datasets for representation gaps. Actively collect and incorporate data from underrepresented areas to create a more balanced dataset.

- Technical Mitigation: Apply algorithmic fairness techniques and bias-correction algorithms during model training and validation.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Resolving Data Inconsistencies in Multi-Source Satellite Feeds

Symptoms: AI model produces erratic or inaccurate predictions; outputs cannot be replicated when different satellite data sources are used.

| Diagnosis Step | Verification Method | Common Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Check Temporal Alignment | Compare timestamps of all input data layers (e.g., optical, SAR, weather). | Implement a data preprocessing pipeline that synchronizes all inputs to a common temporal baseline. |

| Verify Spatial Calibration | Use ground control points (GCPs) to validate geolocation accuracy across different images. | Re-project all data to a consistent coordinate reference system (CRS) and resolution. |

| Confirm Data Preprocessing | Review the steps for atmospheric correction, radiometric calibration, and cloud masking. | Standardize the preprocessing workflow for all incoming data streams using a common framework. |

Guide 2: Addressing High Energy Consumption in AI Model Training

Symptoms: The computational cost of training or running large climate models becomes prohibitive; carbon footprint of research threatens to offset environmental benefits.

| Challenge | Root Cause | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| High Computational Load | Training complex models like high-resolution climate emulators is computationally intensive [35]. | Utilize specialized hardware (e.g., NVIDIA GPUs) and optimized software frameworks (e.g., TensorFlow, PyTorch) to improve FLOPs/watt [35] [38]. |

| Inefficient Model Architecture | Model is larger than necessary for the task. | Employ model compression techniques including pruning, knowledge distillation, and using more efficient architectures (e.g., models based on Spherical Fourier Neural Operators) [35]. |

| Lack of Monitoring | Energy use is not measured or tracked. | Implement AI-driven energy monitoring agents to track the power consumption of IT infrastructure in real-time, allowing for optimization and reduction of waste [38]. |

Experimental Protocol for Energy Consumption Baseline:

- Tooling: Use energy monitoring software (e.g., NVIDIA System Management Interface) coupled with hardware power meters.

- Procedure: Run a standardized benchmark task (e.g., training for 100 iterations on a fixed dataset) on your model.

- Data Collection: Record the total energy consumed (in kWh) and the peak power draw (in kW) throughout the benchmark execution.

- Analysis: Calculate the energy efficiency metric (e.g., samples processed per kWh). Use this baseline to evaluate the effectiveness of subsequent optimization efforts.

Guide 3: Correcting "Model Drift" in Long-Term Climate Forecasting

Symptoms: A model that was initially accurate begins to show increasing error margins in its predictions over time.

Diagnosis Workflow:

Mitigation Steps:

- Data Verification: Confirm that the input data from satellites and other sensors has not changed in format, quality, or distribution.

- Concept Drift Analysis: Statistically compare the data distribution the model was trained on against the current incoming data. In climate science, this could reflect a permanent shift in climate patterns.

- Model Retraining: Implement a continuous learning pipeline that periodically retrains the model on recently collected data to keep it adapted to new conditions.

- Architecture Review: If retraining fails, the model architecture itself may be insufficient to capture new patterns. Explore newer architectures like exascale climate emulators that can achieve higher spatial resolution (e.g., 3.5 km) [35].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Platforms

The following tools and platforms are critical for building and deploying AI-powered satellite analytics systems in climate research.

| Item Name | Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| NVIDIA Earth-2 | AI Platform | Provides a framework for creating AI-powered digital twins of the Earth, enabling high-resolution climate and weather modeling at unprecedented scale and precision [35]. |

| Pinecone / Weaviate | Vector Database | Manages high-dimensional vector data (e.g., satellite image embeddings), enabling efficient similarity search and retrieval for training and inference [36]. |

| LangChain / AutoGen | AI Framework | Facilitates the development of complex, multi-step AI agents that can orchestrate workflows, manage memory, and call specialized tools for tasks like data analysis and compliance checks [36]. |

| OroraTech's CubeSats | Edge AI Hardware | Enables real-time wildfire detection by performing AI inference directly on satellites using NVIDIA Jetson technology, drastically reducing response time [35]. |

| Exascale Climate Emulators | AI Model | Uses neural networks to emulate traditional physics-based climate models, dramatically accelerating the production of high-resolution climate projections for scenario planning [35]. |

| AI Governance Framework | Compliance Software | A structured software solution (e.g., RIA compliance tools) that helps document models, perform risk assessments, and ensure audit trails for regulatory compliance [34]. |

Performance & Compliance Reference Tables

Table 1: AI Model Performance Benchmarks in Climate Applications