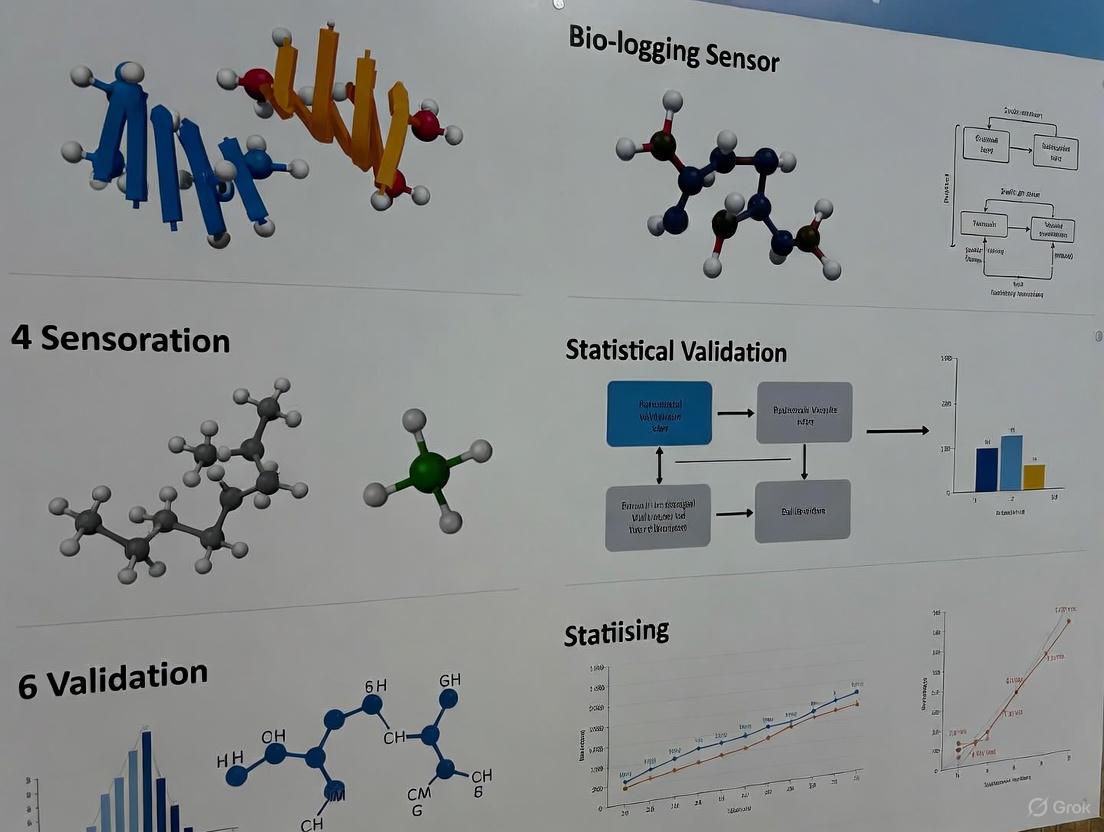

Statistical Validation of Bio-Logging Sensor Data: A Roadmap for Robust Analysis in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on validating and analyzing bio-logging sensor data.

Statistical Validation of Bio-Logging Sensor Data: A Roadmap for Robust Analysis in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on validating and analyzing bio-logging sensor data. It covers the foundational challenges of complex physiological time-series data, explores advanced statistical and machine learning methodologies for data interpretation, addresses common pitfalls in study design and analysis, and outlines rigorous validation frameworks. By synthesizing best practices for ensuring data integrity, from collection through analysis, this resource aims to enhance the reliability of insights derived from bio-logging in translational and clinical research, ultimately supporting more robust drug development and physiological monitoring.

Navigating the Complexities of Bio-Logging Data

Understanding Time-Series Nature and Autocorrelation in Physiological Data

Physiological data obtained from bio-logging sensors presents unique challenges and opportunities for analysis due to its inherent temporal dependencies and sequential nature. Unlike cross-sectional data, physiological time-series data, such as heart rate, cerebral blood flow, or animal movement patterns, are characterized by observations ordered in time, where each data point is dependent on its preceding values. This property, known as autocorrelation, represents the correlation between a time series and its own lagged values over successive time intervals [1]. Understanding and properly accounting for autocorrelation is fundamental to extracting meaningful information from bio-logging data, as it captures the inherent memory and dynamics of physiological systems.

The analysis of these temporal patterns provides critical insights into the underlying physiological states and processes. In cerebral physiology, for instance, continuous monitoring of signals like intracranial pressure (ICP) and brain tissue oxygenation (PbtO2) reveals intricate patterns essential for identifying anomalies and understanding cerebral autoregulation [1]. Similarly, in movement ecology, the analysis of acceleration data from animal-borne devices requires specialized time-series approaches to decode behavior and energy expenditure [2] [3]. The time-series nature of this data necessitates specialized statistical validation methods that respect the temporal ordering and dependencies between observations, moving beyond traditional statistical approaches that assume independent measurements.

Analytical Approaches for Time-Series Data

Foundational Concepts and Challenges

The sequential structure of physiological time-series data creates several analytical challenges. These datasets often exhibit complex autocorrelation structures, where the dependence between observations varies across different time lags, capturing both short-term and long-term physiological rhythms. Additionally, bio-logging data is frequently multivariate, with multiple synchronized physiological parameters recorded simultaneously (e.g., heart rate, breathing rate, and accelerometry), creating high-dimensional datasets with complex inter-channel relationships [4]. The presence of non-stationarity, where statistical properties like mean and variance change over time, further complicates analysis, as many traditional time-series methods assume stationarity.

Another significant challenge in bio-logging research is data scarcity. Despite the potential for continuous monitoring to generate large volumes of data, the complexity and cost of data collection, particularly in wild animals or clinical settings, often result in limited dataset sizes [5]. This limitation is particularly pronounced for rare behaviors or physiological events, creating class imbalance issues that can hinder the development of robust machine learning models. Furthermore, the irregular sampling frequencies caused by device limitations, transmission failures, or animal behavior necessitate methods that can handle missing data and unequal time intervals without compromising the temporal integrity of the dataset [6].

Modeling Techniques and Their Applications

Various modeling approaches have been developed to address the unique characteristics of physiological time-series data, each with distinct strengths for capturing autocorrelation and temporal dynamics.

Table 1: Time-Series Modeling Techniques for Physiological Data

| Model Category | Representative Methods | Key Characteristics | Typical Applications in Physiology |

|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical Models | Vector Autoregressive (VAR), Kalman Filter, ARIMA | Captures linear dependencies, suitable for modeling interdependencies in multivariate systems | Cerebral hemodynamics, vital sign forecasting, ecological driver analysis [1] |

| Deep Learning Models | LSTM, 1D CNN, Temporal Fusion Transformer (TFT) | Captures complex non-linear temporal patterns, handles long-range dependencies | Heart rate prediction, activity recognition, physiological forecasting [7] [8] |

| Feature-Based Methods | TSFRESH, catch22, Statistical moment extraction | Reduces dimensionality while preserving temporal patterns, creates inputs for machine learning | Animal behavior classification, disease state identification, anomaly detection [6] |

| Hybrid Approaches | SSA-LSTM, CNN-LSTM, Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINN) | Combines strengths of multiple approaches, incorporates domain knowledge | Heart rate prediction during exercise, movement ecology, physiological monitoring [8] |

Autoregressive (AR) models and their multivariate extensions form the foundation of many physiological time-series analyses. The vector autoregressive (VAR) model captures the linear interdependencies between multiple time series by representing each variable as a linear combination of its own past values and the past values of all other variables in the system [1]. For a VAR model of order p (VAR(p)), the mathematical formulation is:

Yₜ = c + Σᵢ₌₁ᵖ AᵢYₜ₋ᵢ + εₜ

Where Yₜ is a vector of endogenous variables at time t, Aᵢ are coefficient matrices capturing lagged effects, c is a constant vector, and εₜ represents white noise disturbances [1]. This approach is particularly valuable in cerebral physiology where parameters like intracranial pressure, cerebral blood flow, and oxygenation influence each other through complex feedback loops.

State-space models, including the Kalman filter, provide an alternative framework that introduces the concept of unobservable states representing latent physiological processes that influence observed signals [1]. These models operate through a two-fold process: a state equation describing how the system evolves over time, and an observation equation detailing how unobservable states contribute to observed signals. By iteratively updating estimates of both states and parameters, state-space models offer a comprehensive framework for modeling intricate temporal dependencies in non-stationary physiological data.

More recently, deep learning approaches have demonstrated remarkable capabilities in capturing complex temporal patterns. Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks have proven particularly effective for physiological time-series due to their ability to capture long-range dependencies, making them well-suited for HR prediction and behavioral classification [8]. Temporal Fusion Transformers (TFT) have shown superior performance in multivariate, multi-horizon forecasting tasks, outperforming classical deep learning architectures across various prediction horizons by leveraging attention mechanisms to capture long-sequence dependencies and temporal feature dynamics [7].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Time-Series Models for Physiological Forecasting

| Model | Application Context | Performance Metrics | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temporal Fusion Transformer (TFT) | ICU vital sign forecasting (SpO₂, Respiratory Rate) | Lower RMSE and MAE across all forecasting horizons (7, 15, 25 minutes) compared to LSTM, GRU, CNN [7] | Captures long-sequence dependencies, handles multivariate inputs, provides temporal feature importance |

| SSA-Augmented LSTM | Heart rate prediction during sports activities | Lowest prediction error compared to CNN, PINN, RNN alone [8] | Effectively captures HR dynamics, handles non-linear and non-stationary characteristics |

| Vector Autoregressive (VAR) | Cerebral physiologic signals | Captures interdependencies among multiple cerebral parameters [1] | Models feedback loops, provides interpretable coefficients, well-established statistical properties |

| Kalman Filter | Cerebral physiologic signals | Estimates hidden states from noisy observations [1] | Handles non-stationary data, recursively updates estimates as new data arrives |

Experimental Protocols for Time-Series Analysis

Data Collection and Preprocessing Framework

Robust experimental protocols are essential for valid time-series analysis of physiological data. The data collection phase must carefully consider temporal resolution and sensor synchronization to ensure data quality. For example, in a study predicting heart rate using wearable sensors during sports activities, physiological signals were collected at 1 Hz using the BioHarness 3.0 wearable chest strap device, which provides accurate ECG-derived measurements [8]. The dataset included 126 recordings from 81 participants across 10 different sports, with demographic diversity and varying fitness levels to ensure comprehensive evaluation.

Data preprocessing represents a critical step in preparing physiological time-series for analysis. The protocol typically includes multiple stages: outlier removal using statistical thresholds to identify physiologically implausible values; signal normalization to enable consistent comparison across subjects and activities; and handling of missing data through appropriate imputation methods that preserve temporal dependencies [8]. For multivariate analyses, temporal alignment of all data streams is essential, particularly when sensors have different sampling rates or when data transmission delays occur.

In bio-logging studies, additional preprocessing considerations include tag data recovery and sensor fusion. As described in field studies, recovering data from animal-borne devices often involves navigating challenging terrain to locate tagged animals, with potential issues such as tag detachment or damage from predators [3]. The integration of multiple sensor modalities (GPS, accelerometry, depth, temperature) requires careful time synchronization to enable correlated analysis of behavior, physiology, and environmental context.

Model Validation and Interpretation Methods

Validating time-series models requires specialized approaches that respect temporal dependencies. The cascaded fine-tuning strategy has demonstrated effectiveness in physiological forecasting, where a model is first trained on a general population dataset then sequentially fine-tuned on individual patients' data, significantly enhancing model generalizability to unseen patient profiles [7]. This approach is particularly valuable in clinical contexts where individual physiological patterns vary considerably.

For assessing model performance, time-series cross-validation with temporally ordered splits is essential to avoid data leakage from future to past observations. Standard performance metrics including Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) provide quantitative measures of forecasting accuracy, while feature importance analysis helps interpret model decisions [4]. The Pairwise Importance Estimate Extension (PIEE) method has been adapted for time-series data to estimate the importance of individual time points and channels in multivariate physiological data through an embedded pairwise layer in neural networks [4].

Explainability frameworks are increasingly important for validating time-series models in physiological contexts. The adapted PIEE method generates feature importance heatmaps and rankings that can be verified against ground truth or domain knowledge, providing insights into which physiological channels and time points most influence model predictions [4]. When ground truth is unavailable, ablation studies that retrain models with leave-one-out and singleton feature subsets help verify the contribution of individual features to model performance.

Bio-Logging Platforms and Data Standards

The growing volume of bio-logging data has spurred the development of specialized platforms and standards to facilitate data sharing, preservation, and collaborative research. The Biologging intelligent Platform (BiP) represents an integrated solution for sharing, visualizing, and analyzing biologging data while adhering to internationally recognized standards for sensor data and metadata storage [2]. This platform not only stores sensor data with associated metadata but also standardizes this information to facilitate secondary data analysis across various disciplines, addressing the critical social mission of preserving behavioral and physiological data for future generations.

Standardization initiatives are crucial for enabling meta-analyses and large-scale comparative studies. The International Bio-Logging Society's Data Standardisation Working Group has developed prototypes for data standards to address the risk of most bio-logging data remaining hidden and ultimately lost to the next generation [3]. Complementary projects like the AniBOS (Animal Borne Ocean Sensors) initiative establish global ocean observation systems that leverage animal-borne sensors to gather physical environmental data worldwide, creating valuable datasets for correlating animal physiology with environmental conditions [2].

Research Reagent Solutions for Physiological Monitoring

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Bio-Logging and Physiological Time-Series Analysis

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Research Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wearable Sensors | BioHarness 3.0, Zephyr chest straps, Empatica E4 | Collect physiological signals (ECG, acceleration, breathing rate) in naturalistic settings | Sports science, ecological physiology, clinical monitoring [8] |

| Animal-Borne Devices | Satellite Relay Data Loggers (SRDL), Video loggers, Accelerometry tags | Monitor animal behavior, physiology, and environmental context | Movement ecology, conservation biology, oceanography [2] [9] |

| Data Platforms | Biologging intelligent Platform (BiP), Movebank | Store, standardize, and share bio-logging data with metadata | Collaborative research, meta-analyses, data preservation [2] |

| Analysis Toolkits | TSFRESH, catch22, PyTorch/TensorFlow for time-series | Extract features, build predictive models, analyze temporal patterns | Behavior classification, physiological forecasting, anomaly detection [6] |

| Specialized Analytics | Singular Spectrum Analysis (SSA), Temporal Fusion Transformer (TFT) | Decompose time-series, model complex temporal relationships | Heart rate prediction, vital sign forecasting [7] [8] |

The BioHarness 3.0 represents a typical research-grade wearable monitoring system used for collecting physiological time-series data in sports and ecological contexts. This chest strap device records ECG signals at 250 Hz and automatically computes heart rate, RR intervals, and breathing rate at 1 Hz, providing the multi-parameter physiological time-series essential for understanding complex physiological interactions [8]. For animal studies, Satellite Relay Data Loggers (SRDL) store essential data such as dive profiles and depth-temperature profiles, transmitting compressed data via satellite for over one year, enabling long-term monitoring in species like seals, sea turtles, and marine predators [2].

Advanced video loggers like the LoggLaw CAM have enabled groundbreaking observations of animal behavior in challenging environments, such as capturing king penguin feeding behavior in dark ocean waters, providing rich behavioral context for interpreting physiological time-series data [9]. These devices are increasingly customized for specific research needs, combining multiple sensor modalities including acceleration, depth, temperature, and magnetometry to enable comprehensive studies of animal behavior and physiology in relation to environmental conditions.

The analysis of physiological data from bio-logging sensors requires specialized approaches that respect the time-series nature and autocorrelation structure inherent in these datasets. Understanding these temporal dependencies is not merely a statistical consideration but fundamental to extracting biologically meaningful information from complex physiological systems. The comparative analysis presented in this guide demonstrates that while traditional statistical methods like VAR models and Kalman filters provide interpretable frameworks for modeling physiological dynamics, advanced deep learning approaches like TFT and hybrid models offer superior performance in complex forecasting tasks.

The ongoing development of specialized platforms, data standards, and analytical tools is transforming bio-logging research, enabling larger-scale analyses and more sophisticated modeling approaches. As these technologies continue to evolve, researchers must maintain focus on rigorous statistical validation methods that properly account for temporal dependencies, ensuring that conclusions drawn from physiological time-series data are both statistically sound and biologically relevant. The integration of explainability frameworks will further enhance the interpretability and utility of complex models, ultimately advancing our understanding of physiological systems across diverse contexts from clinical medicine to wildlife ecology.

The rapid growth of biologging technology has fundamentally transformed wildlife ecology and conservation research, providing unprecedented insights into animal physiology, behavior, and movement [10] [11]. However, this technological advancement is outpacing the development of robust ethical and methodological safeguards, creating significant statistical challenges that researchers must navigate [10]. The analysis of biologging data presents unique methodological hurdles due to the complex nature of time-series information, which often exhibits strong autocorrelation, intricate random effect structures, and inherent heterogeneity across multiple biological levels [12]. These challenges are further compounded by frequent small sample sizes resulting from natural history constraints, political sensitivity, funding limitations, and the logistical difficulties of studying cryptic or endangered species [13].

The convergence of these statistical challenges—small sample sizes, complex random effects, and substantial heterogeneity—creates a perfect storm that can compromise data validity and ecological inference if not properly addressed. This guide examines these interconnected challenges through the lens of biologging sensor data validation, comparing methodological approaches and providing experimental protocols to enhance statistical rigor in wildlife studies.

Comparative Analysis of Key Statistical Challenges

Table 1: Comparison of Key Statistical Challenges in Bio-logging Research

| Challenge | Impact on Data Analysis | Common Consequences | Recommended Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small Sample Sizes | Reduced statistical power; difficulty evaluating model assumptions; increased sensitivity to outliers [13] | Type I/II errors; overfitted models; limited generalizability [13] | Contingent analysis approach; robust variance estimation; simulation-based validation [13] [14] |

| Complex Random Effects | Temporal autocorrelation; non-independence of residuals; hierarchical data structures [12] | Inflated Type I error rates; incorrect variance partitioning; biased parameter estimates [12] | AR/ARMA models; generalized least squares; specialized correlation structures [12] |

| Heterogeneity | Between-study variability; divergent treatment effects; subgroup differences [15] [16] | Misleading summary estimates; obscured subgroup effects; reduced predictive accuracy [15] | Random-effects meta-analysis; subgroup pattern plots; mixture models [17] [15] |

Table 2: Analytical Approaches for Small Sample Size Scenarios

| Method | Application Context | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Contingent Analysis [13] | Stepwise model building with small datasets (n < 30) | Heuristic value; hypothesis generation; accommodates biological insight | Potential for overfitting; multiple testing concerns |

| Simulation-Based Validation [14] | Bio-logger configuration and activity detection | Tests data collection strategies; reproducible parameter optimization | Requires substantial preliminary data collection |

| Adjusted R² & Mallow's Cp [13] | Model selection with limited observations | Balances model complexity and predictive accuracy | Becomes unreliable when predictors > > sample size |

Small Sample Size Challenges: Experimental Protocols and Solutions

The Nature of the Problem

Small sample sizes present structural problems for biologging researchers, including difficulties in evaluating analytical assumptions, ambiguous model evaluation, and increased susceptibility to outliers and influential points [13]. In wildlife ecology, administrative constraints, political sensitivities, and natural history factors often limit sample sizes, with many studies lasting only 2-3 years on average [13]. This problem is particularly acute for species with sparse distributions or those occupying high trophic levels, such as bears, wolves, and large carnivores.

Experimental Protocol: Contingent Analysis Approach

The contingent analysis methodology provides a structured approach for small sample size scenarios, as demonstrated in barn owl reproductive success research [13]:

Initial Data Exploration: Plot response variables against each explanatory variable to assess relationship nature (linear vs. non-linear) and identify unusual observations [13].

Collinearity Assessment: Examine explanatory variables for intercorrelations that might destabilize parameter estimates.

Model Screening: Fit all possible regression models and screen candidates using adjusted R², Mallow's Cp, and residual mean square statistics [13].

Model Validation: Compute PRESS (Prediction Sum of Squares) statistics for top candidate models by systematically excluding each observation and predicting it from the remaining data [13].

Diagnostic Evaluation: Examine residuals for linearity, normality, and homoscedasticity assumptions; assess influence of individual data points.

Biological Interpretation: Select final model based on statistical criteria and biological plausibility [13].

This protocol emphasizes a deliberate, iterative approach that balances statistical rigor with biological insight, particularly valuable when sample sizes are insufficient for automated model selection procedures.

Contingent Analysis Workflow: A sequential approach to small sample size analysis emphasizing iterative evaluation and biological insight.

Complex Random Effects in Time-Series Data

Autocorrelation Structures in Biologging Data

Biologging technology generates complex time-series data where successive measurements are often dependent on prior values, creating significant analytical challenges [12]. This temporal autocorrelation manifests across various physiological metrics, including electrocardiogram readings, body temperature fluctuations, blood oxygen levels during diving, and accelerometry signals [12]. Ignoring these dependencies violates the independence assumption of standard statistical tests, dramatically inflating Type I error rates—in some simulated scenarios reaching 25.5% compared to the nominal 5% level [12].

Experimental Protocol: Time-Series Modeling for Physiological Data

Proper analysis of biologging time-series data requires specialized analytical approaches:

Avoid Inappropriate Methods: Never use t-tests or ordinary generalized linear models for data exhibiting temporal trends, as these greatly inflate Type I error rates [12].

Select Correlation Structures: Implement autoregressive (AR), moving average (MA), or combined (ARMA) models to account for temporal dependencies. AR(1) models are frequently used, with the parameter rho (ρ) indicating the strength of correlation between consecutive residuals [12].

Model Fitting and Assessment: Utilize generalized least squares (GLS) models with appropriate correlation structures to control Type I error rates at acceptable levels [12].

Heterogeneity Evaluation: Account for non-constant variance structures that may accompany autocorrelation patterns.

Biological Interpretation: Relate statistical findings to underlying biological processes, such as circadian rhythms in body temperature or oxygen store depletion during dives [12].

This protocol emphasizes the critical importance of selecting appropriate correlation structures for time-series data, as failure to do so can lead to substantially inflated false positive rates and incorrect biological inferences.

Heterogeneity in Treatment Effects and Biological Responses

Heterogeneity represents the variability in treatment effects or biological responses across individuals, subpopulations, or studies. In biologging research, this may manifest as differential movement patterns, physiological responses, or behavioral adaptations to environmental changes [11]. The standard random-effects meta-analysis model typically assumes normally distributed effects, but this assumption may not always be plausible, potentially obscuring important biological patterns [15].

Experimental Protocol: Subpopulation Treatment Effect Pattern Plots (STEPP)

The STEPP methodology provides a non-parametric approach to exploring heterogeneity patterns:

Subpopulation Construction: Create overlapping subpopulations along the continuum of a covariate (e.g., biomarker levels, environmental gradients) to improve precision of estimated effects [17].

Effect Estimation: Calculate absolute treatment effects (e.g., differences in cumulative incidence) or relative effects (e.g., hazard ratios) within each subpopulation [17].

Stability Assurance: Pre-specify the number of events within subpopulations to ensure analytical stability; simulation studies recommend a minimum of 20 events per subpopulation [17].

Graphical Presentation: Plot estimated effects against covariate values to visualize potential patterns of heterogeneity [17].

Statistical Testing: Employ permutation-based inference to test the null hypothesis of no heterogeneity while controlling Type I error rates [17].

This approach is particularly valuable for identifying complex, non-linear patterns of treatment effect heterogeneity that might be missed by traditional regression models with simple interaction terms.

Heterogeneity Analysis Workflow: A non-parametric approach to identifying complex patterns in treatment effects across subpopulations.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Methodological Tools for Addressing Statistical Challenges

| Tool/Technique | Primary Function | Application Context | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| R package metafor [18] | Random-effects meta-analysis | Synthesis of multiple biologging studies | Handles complex dependence structures; multiple estimation methods |

| R package metaplus [15] | Robust meta-analysis | Downweighting influential studies | t-distribution random effects; accommodation of heavy-tailed distributions |

| QValiData Software [14] | Simulation-based validation | Bio-logger configuration testing | Synchronizes video and sensor data; reproducible parameter optimization |

| STEPP Methodology [17] | Heterogeneity visualization | Exploring treatment-covariate patterns | Non-parametric; overlapping subpopulations; complex pattern detection |

| Generalized Least Squares [12] | Autocorrelation modeling | Time-series biologging data | Flexible correlation structures; controls Type I error inflation |

| Contingent Analysis [13] | Small sample modeling | Limited observation scenarios | Iterative approach; biological insight integration; multiple diagnostics |

Integrated Validation Framework

Simulation-Based Validation Protocol

Simulation-based validation provides a powerful approach for addressing multiple statistical challenges simultaneously, particularly for bio-logger configuration and analytical validation [14]:

Raw Data Collection: Deploy validation loggers that continuously record full-resolution sensor data alongside synchronized video observations [14].

Behavioral Annotation: Systematically annotate video recordings to establish ground truth for behavioral states or events of interest.

Software Simulation: Implement bio-logger sampling and summarization strategies in software to process raw sensor data using various parameter configurations [14].

Performance Evaluation: Compare simulated outputs with video-based behavioral annotations to assess detection accuracy, precision, and recall.

Parameter Optimization: Iteratively refine activity detection thresholds and sampling parameters to balance sensitivity and specificity [14].

Field Deployment: Apply optimized configurations to actual bio-loggers for field data collection.

This validation framework is particularly valuable for maximizing the information yield from hard-won biologging datasets, especially when small sample sizes, complex dependencies, and heterogeneous responses pose significant analytical challenges.

The convergence of small sample sizes, complex random effects, and substantial heterogeneity presents significant but manageable challenges in biologging research. By employing specialized methodological approaches—including contingent analysis for small samples, appropriate time-series models for autocorrelated data, and flexible heterogeneity assessments—researchers can enhance the validity and biological relevance of their findings. The statistical toolkit for addressing these challenges continues to evolve, with simulation-based validation providing particularly promising approaches for optimizing bio-logger configurations and analytical strategies. As biologging technology advances, maintaining methodological rigor while accommodating real-world constraints remains essential for generating robust ecological insights and effective conservation outcomes.

The Critical Impact of Temporal Autocorrelation on Type I Error Rates

In the field of bio-logging research, where scientists rely on animal-borne sensors to collect behavioral, physiological, and movement data, temporal autocorrelation presents a fundamental statistical challenge that compromises the validity of research findings. Autocorrelation refers to the phenomenon where measurements collected close in time tend to be more similar than those further apart, creating a pattern of time-dependent correlation within a data series. A fundamental assumption of many statistical tests—including ANOVA, t-tests, and chi-squared tests—is that sample data are independent and identically distributed. When this assumption is violated due to autocorrelation, the statistical tests produce artificially low p-values, leading to an increased risk of Type I errors (false positives) [19].

The stakes for accurate statistical inference are particularly high in bio-logging studies, where research outcomes may inform conservation policies, animal management strategies, and ecological theory. As biologging has revolutionized studies of animal ecology across diverse taxa, the multidisciplinary nature of the field often means researchers must navigate statistical pitfalls without formal training in time series analysis [20]. This article examines how temporal autocorrelation inflates Type I error rates, provides quantitative evidence from simulation studies, outlines methodological approaches for robust analysis, and offers practical solutions for researchers working with bio-logging sensor data.

Theoretical Framework: How Autocorrelation Inflates Statistical Significance

The Mechanistic Link Between Autocorrelation and Type I Errors

Temporal autocorrelation inflates Type I error rates through a specific mechanistic pathway: it causes an underestimation of the true standard error of parameter estimates. In classical statistical analysis, the standard error of the mean is typically calculated as ( s/\sqrt{n} ), where ( s ) is the sample standard deviation and ( n ) is the sample size. This formula assumes data independence. With autocorrelated data, each observation contains redundant information about neighboring values, effectively reducing the number of independent observations [19].

The consequence is that the calculated standard error underestimates the true variability of the parameter estimate. When this underestimated standard error is used as the denominator in test statistics (such as the t-statistic), the result is an inflated test statistic value, which in turn leads to artificially small p-values. This increases the likelihood of incorrectly rejecting a true null hypothesis—the definition of a Type I error. The relationship between autocorrelation strength and Type I error inflation can be quantified through Monte Carlo simulations, as demonstrated in the following section [19].

Visualizing the Impact of Autocorrelation on Statistical Inference

The diagram below illustrates the causal pathway through which temporal autocorrelation leads to increased Type I errors in bio-logging research.

Pathway from Autocorrelation to Type I Error Inflation

This visualization shows how temporal autocorrelation initiates a cascade of statistical consequences, beginning with the violation of core statistical assumptions and culminating in inflated false positive rates. The red nodes represent problematic statistical conditions, while the green node indicates the ultimate negative outcome for research validity.

Quantitative Evidence: Measuring the Magnitude of Error Rate Inflation

Monte Carlo Simulation Evidence

Monte Carlo simulations provide compelling quantitative evidence of how autocorrelation strength directly impacts Type I error rates. In a simulation study examining the effect of temporal autocorrelation on t-test performance, researchers generated data with first-order autoregressive structure (AR1) with autocorrelation parameter ( \lambda ) ranging from 0 to 0.9. Each simulation used a sample size of 10, with 10,000 iterations per ( \lambda ) value to ensure robust error rate estimation [19].

Table 1: Type I Error Rate Inflation with Increasing Autocorrelation

| Autocorrelation Strength (λ) | Empirical Type I Error Rate | Error Rate Relative to Nominal α (5%) |

|---|---|---|

| 0.0 | 5.0% | 1.0x |

| 0.1 | 6.5% | 1.3x |

| 0.2 | 9.1% | 1.8x |

| 0.3 | 13.2% | 2.6x |

| 0.4 | 18.9% | 3.8x |

| 0.5 | 26.5% | 5.3x |

| 0.6 | 36.3% | 7.3x |

| 0.7 | 48.3% | 9.7x |

| 0.8 | 62.1% | 12.4x |

| 0.9 | 77.5% | 15.5x |

The results demonstrate a dramatic exponential increase in Type I error rates as autocorrelation strengthens. At ( \lambda = 0.9 ), the empirical Type I error rate reached 77.5%—more than 15 times the nominal 5% significance level. This means that with strongly autocorrelated data, researchers have a approximately 3 in 4 chance of obtaining a statistically significant result even when no true effect exists [19].

Comparative Performance of Study Designs Against Autocorrelation

Research design plays a critical role in mitigating the effects of autocorrelation. A simulation study comparing wildlife control interventions evaluated the false positive rates (Type I errors) of five common study designs under various confounding interactions, including temporal autocorrelation [21].

Table 2: False Positive Rates by Study Design in the Presence of Confounding

| Study Design | Description | False Positive Rate with Background Interactions | False Positive Rate with Temporal Autocorrelation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simple Correlation | Compares different doses of intervention and outcomes without within-subject comparisons | 5.5%-6.8% | 3.8%-5.3% |

| nBACI | Non-randomized Before-After-Control-Impact design | 51.5%-54.8% | 4.5%-5.0% |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial | 6.8%-7.5% | 5.3%-7.5% |

| rBACI | Randomized Before-After-Control-Impact design | 4.0%-6.0% | 4.8%-6.0% |

| Crossover Design | Within-subject analysis with reversal of treatment conditions | 6.8% | 3.5%-4.3% |

The results reveal striking differences in robustness to confounding factors. Non-randomized designs (nBACI) exhibited alarmingly high false positive rates (exceeding 50%) when background interactions were present, while randomized designs with appropriate safeguards maintained much lower error rates. This underscores the critical importance of randomized designs in bio-logging research where autocorrelation and other confounders are prevalent [21].

Methodological Approaches: Detection and Remediation Strategies

Statistical Framework for Autocorrelation Assessment

The statistical foundation for understanding autocorrelation begins with defining the autoregressive process. A first-order autoregressive time series (AR1) in the error terms follows this structure [19]:

[ Yi = \mu + \etai ] [ \etai = \lambda\eta{i-1} + \varepsilon_i, \quad i = 1, 2, \dots ]

where ( -1 < \lambda < 1 ) and the ( \varepsiloni ) are independent, identically distributed random variables drawn from a normal distribution with mean zero and variance ( \sigma^2 ). The ( \etai ) are the autoregressive error terms. This can be simplified by substituting:

[ \etai = Yi - \mu ] [ \eta{i-1} = Y{i-1} - \mu ]

into the above equation to obtain:

[ Yi - \mu = \lambda(Y{i-1} - \mu) + \varepsilon_i, \quad i = 1, 2, \dots ]

For hypothesis testing where the null hypothesis assumes ( \mu = 0 ), the equation becomes:

[ Yi = \lambda Y{i-1} + \varepsilon_i, \quad i = 1, 2, \dots ]

This formal structure enables researchers to explicitly model and test for the presence of autocorrelation in their data series.

Detection Methods for Temporal Autocorrelation

Several statistical approaches are available for detecting temporal autocorrelation in bio-logging data:

Autocorrelation Function (ACF) Analysis: The sample ACF is defined for a realization ( (z1, \cdots, zn) ) as:

[ \hat{\rho}(h) = \frac{\sum{j=1}^{n-h}(z{j+h} - \bar{z})(zj - \bar{z})}{\sum{j=1}^{n}(z_j - \bar{z})^2}, \quad h = 1, \cdots, n-1 ]

For white noise processes, the theoretical ACF is null for any lag ( h \neq 0 ). For moving average processes of order q (MA(q)), the theoretical ACF vanishes beyond lag q [22].

Ljung-Box Test: This portmanteau test examines whether autocorrelations for a group of lags are significantly different from zero. However, recent research suggests limitations with this test, as it may be "excessively liberal" in the presence of certain data structures [23] [22].

Empirical Likelihood Ratio Test (ELRT): A robust alternative for AR(1) model identification, the ELRT maintains nominal Type I error rates more accurately while exhibiting superior power compared to the Ljung-Box test. Simulation results indicate that the ELRT achieves higher statistical power in detecting subtle departures from the AR(1) structure [23].

Analytical Workflow for Autocorrelation-Aware Analysis

The diagram below outlines a comprehensive analytical workflow for addressing temporal autocorrelation in bio-logging research, from study design through final analysis.

Analytical Workflow for Autocorrelation-Aware Analysis

This workflow emphasizes proactive consideration of autocorrelation throughout the research process, rather than as an afterthought. The yellow nodes represent diagnostic steps, while green nodes indicate remedial approaches that address identified autocorrelation.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Methods for Robust Inference

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Autocorrelation Challenges

| Method Category | Specific Techniques | Primary Function | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study Design | Randomized Controlled Trials (RCT), Crossover Designs, BACI Designs | Minimize confounding and selection bias through random assignment and within-subject comparisons | RCT and rBACI designs show significantly lower false positive rates compared to non-randomized designs [21] |

| Detection Methods | ACF/PACF plots, Ljung-Box test, Empirical Likelihood Ratio Test (ELRT) | Identify presence and structure of temporal dependence | ELRT shows superior power and better control of Type I error compared to Ljung-Box test [23] |

| Modeling Approaches | ARIMA models, Generalized Least Squares, Mixed Effects Models, Generalized Estimating Equations | Account for autocorrelation structure in parameter estimation | Mixed effects models particularly effective for hierarchical bio-logging data with repeated measures |

| Validation Techniques | Residual diagnostics, Cross-validation, Independent test sets | Verify model adequacy and generalizability | 79% of accelerometer-based ML behavior classification studies insufficiently validated models, risking overfitting [24] |

| Specialized Software | R (forecast, nlme, lme4 packages), Python (statsmodels, scikit-learn), Custom simulation code | Implement specialized analyses for autocorrelated data | Simulation-based validation enables testing of analysis methods before field deployment [14] |

Temporal autocorrelation presents a serious threat to statistical conclusion validity in bio-logging research, dramatically inflating Type I error rates beyond nominal significance levels. The quantitative evidence presented here reveals that under moderate to strong autocorrelation, false positive rates can exceed 50%—an order of magnitude greater than the conventional 5% threshold. This problem is particularly acute in bio-logging studies where automated sensors generate inherently autocorrelated data streams.

Addressing this challenge requires a multifaceted approach: (1) implementing robust study designs like randomized controlled trials with appropriate safeguards; (2) routinely screening for autocorrelation during exploratory data analysis; (3) applying appropriate modeling techniques that explicitly account for temporal dependence; and (4) validating models with independent data to detect overfitting. The Empirical Likelihood Ratio Test offers a promising alternative to traditional autocorrelation tests, providing better control of Type I errors while maintaining higher statistical power [23].

By adopting these practices, researchers can substantially improve the reliability and reproducibility of findings derived from bio-logging data. The methodological framework presented here provides a pathway toward more statistically valid inference in movement ecology, conservation biology, and related fields that depend on accurate interpretation of autocorrelated sensor data.

Advanced Analytical Techniques for Sensor Data Interpretation

Applying Mixed Models and Generalized Least Squares (GLS) for Complex Data Structures

In biological and medical research, data often exhibit complex structures that violate the fundamental assumption of independence inherent in standard statistical tests. Mixed Models (also known as Multilevel or Hierarchical Linear Models) and Generalized Least Squares (GLS) provide sophisticated analytical frameworks for such data. Mixed Models extend traditional regression by incorporating both fixed and random effects, making them particularly suitable for hierarchical data structures, repeated measurements, and correlated observations commonly encountered in longitudinal studies, genetic research, and experimental designs with nested factors [25] [26]. GLS offers a flexible approach for handling heteroscedasticity and autocorrelation in datasets where the assumption of constant variance is violated [27].

These methods are especially relevant for bio-logging sensor data statistical validation, where measurements are often collected sequentially over time from the same subjects or devices, creating inherent correlations that must be accounted for to ensure valid inference. This guide provides an objective comparison of these approaches, their performance characteristics, and implementation considerations for researchers and drug development professionals.

Theoretical Foundations and Methodologies

Mixed Effects Models: Framework and Applications

Linear Mixed Effects Models (LMMs) incorporate both fixed and random effects to handle non-independent data structures. The general form of an LMM can be expressed as:

Y = Xβ + Zb + ε

Where Y is the response vector, X is the design matrix for fixed effects, β represents fixed effect coefficients, Z is the design matrix for random effects, b represents random effects (typically assumed ~N(0, D)), and ε represents residuals (~N(0, R)) [25] [26]. The key advantage of this formulation is its ability to model variance at multiple levels, enabling researchers to partition variability into within-group and between-group components while controlling for non-independence among clustered observations [25].

Mixed models are particularly valuable in biological applications for several reasons: they appropriately handle hierarchical data structures (e.g., repeated measurements nested within individuals); they allow for the estimation of both population-level (fixed) effects and group-specific (random) effects; and they can accommodate unbalanced designs with missing data under the Missing at Random (MAR) assumption [27] [25]. In the context of bio-logging sensor data, this capability is crucial for analyzing temporal patterns collected from multiple sensors deployed on different subjects across varying environmental conditions.

Generalized Least Squares (GLS): Framework and Applications

Generalized Least Squares extends ordinary least squares regression by allowing for non-spherical errors with known covariance structure. The GLS estimator is given by:

β̂ = (XᵀΩ⁻¹X)⁻¹XᵀΩ⁻¹Y

Where Ω is the covariance matrix of the errors [27]. By appropriately specifying Ω, GLS can account for various correlation structures and heteroscedasticity patterns in the data. Unlike mixed models, GLS does not explicitly model random effects but focuses on correctly specifying the covariance structure of the errors to obtain efficient parameter estimates and valid inference.

GLS is particularly useful in longitudinal data analysis where measurements taken closer in time may be more highly correlated than those taken further apart. The Covariance Pattern Model (CPM) approach, a specific implementation of GLS, allows researchers to specify various correlation structures for the residuals (e.g., autoregressive, compound symmetry) [27]. This flexibility makes GLS valuable for bio-logging data validation where sensor measurements may exhibit specific temporal correlation patterns that need to be explicitly modeled.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Mixed Models and GLS

| Feature | Mixed Effects Models | Generalized Least Squares (GLS) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Approach | Explicit modeling of fixed and random effects | Generalized regression with correlated errors |

| Handling Dependence | Through random effects structure | Through residual covariance matrix |

| Missing Data | Handles MAR data appropriately | Requires careful implementation for MAR |

| Implementation Complexity | Higher (variance components estimation) | Moderate (covariance pattern specification) |

| Computational Demand | Higher for large datasets | Generally efficient |

| Primary Applications | Hierarchical data, repeated measures, genetic studies | Longitudinal data, spatial correlation, economic data |

Comparative Performance Analysis

Statistical Performance with Complex Data Structures

Simulation studies provide critical insights into the relative performance of different statistical approaches under controlled conditions. Research comparing methods for analyzing longitudinal data with dropout mechanisms has demonstrated that Mixed Models and GLS/Covariance Pattern Models maintain appropriate Type I error rates and provide unbiased estimates under both Missing Completely at Random (MCAR) and Missing at Random (MAR) scenarios [27].

In one comprehensive simulation study examining longitudinal cohort data with dropout, Linear Mixed Effects (LME) models and Covariance Pattern (CP) models produced unbiased estimates with confidence interval coverage close to the nominal 95% level, even with 40% MAR dropout. In contrast, methods that discard incomplete cases (e.g., repeated measures ANOVA and paired t-tests) displayed increasing bias and deteriorating coverage with higher dropout percentages [27]. This performance advantage is particularly relevant for bio-logging sensor data, where missing observations frequently occur due to device malfunction, environmental interference, or subject non-compliance.

For genetic association studies, Mixed Linear Model Association (MLMA) methods have shown nearly perfect correction for confounding due to population structure, effectively controlling false-positive associations while increasing power by applying structure-specific corrections [28]. An important consideration in implementation is the exclusion of the candidate marker from the genetic relationship matrix when using MLMA, as inclusion can lead to reduced power due to "proximal contamination" where the marker is effectively double-fit in the model [28].

Computational Considerations and Implementation

The computational demands of Mixed Models have historically limited their application to large datasets, but recent methodological advances have substantially improved their scalability. The computational complexity of different Mixed Model implementations varies considerably:

Table 2: Computational Characteristics of Mixed Model Implementations

| Method | Building GRM | Variance Components | Association Statistics |

|---|---|---|---|

| EMMAX | O(MN²) | O(N³) | O(MN²) |

| FaST-LMM | O(MN²) | O(N³) | O(MN²) |

| GEMMA | O(MN²) | O(N³) | O(MN²) |

| GRAMMAR-Gamma | O(MN²) | O(N³) | O(MN) |

| GCTA | O(MN²) | O(N³) | O(MN²) |

Note: N = number of samples, M = number of markers [28]

GRAMMAR-Gamma offers computational advantages for analyses involving multiple phenotypes by reducing the cost of association testing from O(MN²) to O(MN), providing significant efficiency gains in large-scale studies [28]. For standard applications, approximate methods that estimate variance components once using all markers (rather than separately for each candidate marker) offer substantial computational savings with minimal impact on results when marker effects are small [28].

Experimental Protocols and Applications

Protocol for Longitudinal Data Analysis with Dropout

The following experimental protocol, adapted from simulation studies on longitudinal cohort data, provides a framework for comparing Mixed Models and GLS approaches [27]:

Data Generation: Simulate longitudinal data for a realistic observational study scenario (e.g., health-related quality of life measurements in children undergoing medical interventions). Generate data for multiple time points (e.g., 0, 3, 6, and 12 months) with predetermined trajectory patterns.

Missing Data Mechanism: Introduce monotone missing data (dropout) under different mechanisms:

- MCAR: Dropout probability is equal for all individuals

- MAR: Dropout probability depends on observed characteristics (e.g., baseline values)

Analysis Methods Application:

- Implement Linear Mixed Effects (LME) models with random intercepts

- Apply Covariance Pattern Models (GLS) with appropriate correlation structures

- Compare against traditional methods (e.g., repeated measures ANOVA, t-tests) as benchmarks

Performance Evaluation:

- Assess bias in estimated marginal means

- Compute coverage probabilities of 95% confidence intervals

- Evaluate statistical power for key contrasts (e.g., within-group change from baseline, between-group differences)

This protocol can be adapted for bio-logging sensor data validation by incorporating sensor-specific characteristics such as measurement frequency, expected temporal correlation structures, and sensor-specific missing data mechanisms.

Protocol for Genetic Association Studies

For genetic applications, the following protocol enables performance comparison of Mixed Model approaches [28]:

Data Simulation: Generate genotype and phenotype data for a quantitative trait with known genetic architecture, varying parameters such as sample size (N), number of markers (M), and heritability (hg²).

Model Implementation:

- Implement MLMA with candidate marker excluded (MLMe)

- Implement MLMA with candidate marker included (MLMi)

- Compare against standard linear regression as a benchmark

Performance Metrics:

- Compute mean association statistics (λmean) for each approach

- Evaluate power to detect true associations

- Assess false positive rates under the null hypothesis

Computational Benchmarking: Compare computation time and memory usage across different implementations (EMMAX, FaST-LMM, GEMMA, GRAMMAR-Gamma, GCTA).

Experimental Protocol for Genetic Association Studies

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Analytical Solutions

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Mixed Model and GLS Analyses

| Tool/Software | Primary Function | Key Features | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| lme4 (R) | Linear Mixed Effects Modeling | Flexible formula specification, handling of crossed random effects | Requires careful specification of random effects structure |

| nlme (R) | Linear and Nonlinear Mixed Effects | Correlation structures, variance functions | Suitable for complex hierarchical structures |

| GEMMA | Genome-wide Mixed Model Association | Efficient exact MLMA implementation | Handles large genetic datasets |

| GCTA | Genetic Relationship Matrix Analysis | Heritability estimation, MLMA | Useful for genetic association studies |

| EMMAX | Efficient Mixed Model Association | Approximate MLMA method | Computational efficiency for large datasets |

| FaST-LMM | Factored Spectrally Transformed LMM | Exact MLMA with computational efficiency | Reduces time complexity for association testing |

Decision Framework and Implementation Guidelines

Model Selection Criteria

Selecting between Mixed Models and GLS approaches depends on several factors, including research questions, data structure, and implementation constraints. Key considerations include:

Research Objective: Mixed Models are preferable when estimating variance components or making inferences about group-level effects is important. GLS/Covariance Pattern Models may be sufficient when the primary interest is in population-average effects with appropriate adjustment for correlation structure [26].

Data Structure: For highly hierarchical data with multiple levels of nesting (e.g., repeated measurements within subjects within clinics), Mixed Models with appropriate random effects provide the most flexible framework. For longitudinal data with specific correlation patterns that decay over time, GLS with autoregressive covariance structures may be most appropriate [27].

Missing Data Mechanism: Under Missing at Random conditions, Mixed Models provide valid inference using all available data, while complete-case methods like repeated measures ANOVA introduce bias [27].

Computational Resources: For very large datasets (e.g., genome-wide association studies), approximate Mixed Model implementations like EMMAX or GRAMMAR-Gamma offer computational advantages with minimal impact on results when effect sizes are small [28].

Decision Framework for Model Selection

Implementation Recommendations for Bio-logging Sensor Data

For bio-logging sensor data validation, the following evidence-based recommendations emerge from comparative studies:

Address Temporal Correlation: Bio-logging data typically exhibit serial correlation. Both Mixed Models (with appropriate random effects) and GLS (with structured covariance matrices) can effectively account for this dependence, with choice depending on whether subject-specific inference (favoring Mixed Models) or population-average effects (favoring GLS) is of primary interest [27] [26].

Handle Missing Data Appropriately: Sensor data frequently contain missing measurements due to technical issues. Mixed Models provide valid inference under MAR conditions without discarding partial records, maximizing power and minimizing bias [27].

Model Selection and Validation: Use information criteria (AIC, BIC) for comparing model fit, but prioritize theoretical justification and research questions. Implement sensitivity analyses to assess robustness to different correlation structures or random effects specifications [25] [29].

Computational Efficiency: For large-scale sensor data with frequent measurements, consider approximate estimation methods or dimension reduction techniques to maintain computational feasibility without sacrificing validity [28].

The application of these advanced statistical methods to bio-logging sensor data validation ensures that conclusions account for the complex correlation structures inherent in such data, leading to more reproducible findings and validated sensor outputs for research and clinical applications.

The analysis of bio-logging sensor data presents unique computational challenges, including complex, non-linear relationships within data streams, high-dimensional feature spaces, and the persistent issue of limited labeled data for model training. Within this domain, Random Forests (RF) and Deep Neural Networks (DNNs) have emerged as two of the most prominent machine learning architectures, each with distinct strengths and operational paradigms [30] [31]. RF, an ensemble method based on decision trees, is celebrated for its robustness and ease of use, particularly with structured, tabular data. In contrast, DNNs, with their multiple layers of interconnected neurons, excel at automatically learning hierarchical feature representations from raw, high-dimensional data such as accelerometer streams or images [32].

The selection between these models is not merely a technical preference but a critical decision that impacts the reliability and interpretability of scientific findings. This guide provides an objective comparison of their performance across various ecological and biological data tasks, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies, to equip researchers with the evidence needed to inform their model selection.

The table below summarizes key performance metrics for Random Forest and Deep Neural Networks from recent studies across various bio-logging and biological data tasks.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Random Forest and Deep Neural Networks

| Application Domain | Model Type | Key Performance Metrics | Noteworthy Strengths | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Animal Behavior Classification (Bio-logger Data) [31] | Classical ML (incl. RF) | Evaluated on BEBE benchmark; outperformed by DNNs across all 9 datasets. | - | Lower accuracy compared to deep learning counterparts. |

| Deep Neural Networks (DNN) | Out-performed classical ML across all 9 diverse BEBE datasets. | Superior accuracy on raw sensor data. | ||

| Self-Supervised DNN (Pre-trained) | Out-performed other DNNs, especially with low training data. | Reduces required annotated data; excellent for cross-species generalization. | ||

| Forest Above Ground Biomass (AGB) Estimation (Remote Sensing) [33] | Random Forest (RF) | R²: 0.95 (Training), 0.75 (Validation); RMSE: 18.46 (Training), 34.52 (Validation). | Handles topographic, spectral, and textural data effectively; robust with multisource data. | |

| Gene Expression Data Classification (Bioinformatics) [34] | Forest Deep Neural Network (fDNN) | Demonstrated better classification performance than ordinary RF and DNN. | Mitigates overfitting in "n << p" scenarios; learns sparse feature representations. | |

| Real-Time Animal Detection (Camera Traps, UAV) [35] | YOLOv7-SE / YOLOv8 (CNN-based) | Up to 94% mAP (controlled illumination); ≥ 60 FPS. | Superior real-time performance on UAV imagery. | Constrained by edge-device memory; cross-domain generalization challenges. |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Validating Animal Behavior Classification on the BEBE Benchmark

The Bio-logger Ethogram Benchmark (BEBE) provides a standardized framework for evaluating behavior classification models across 1654 hours of data from 149 individuals across nine taxa [31].

- Data Preparation: The benchmark comprises tri-axial accelerometer, gyroscope, and environmental sensor data. Data is segmented into windows, and for classical ML models, hand-crafted features (e.g., mean, variance, frequency-domain features) are extracted from each window. For DNNs, raw or minimally processed data windows are used directly.

- Model Training and Validation:

- Classical ML (RF): A Random Forest model is trained on the extracted features. The model's hyperparameters (e.g., number of trees, maximum depth) are tuned via cross-validation on the training set.

- Deep Neural Networks: A DNN (e.g., Convolutional or Recurrent Neural Network) is trained on the raw data windows. The network architecture is optimized for the task.

- Self-Supervised DNN: A DNN is first pre-trained on a large, unlabeled dataset (e.g., 700,000 hours of human accelerometer data) using a self-supervised auxiliary task. This pre-trained model is then fine-tuned on the labeled BEBE data.

- Evaluation: Model performance is evaluated on a held-out test set using metrics like accuracy, F1-score, and precision-recall curves. Crucially, the test set is kept entirely independent and unseen during training to prevent data leakage and overfitting [24] [31].

Protocol 2: Estimating Forest Above Ground Biomass with Random Forest

This protocol details the use of RF for estimating Above Ground Biomass (AGB) by fusing multisensor satellite data [33].

- Data Acquisition and Fusion: Data from Sentinel-2 (optical), Sentinel-1 (SAR), and GEDI (LiDAR) are acquired and processed on the Google Earth Engine (GEE) cloud platform. These data provide spectral, topographic, and textural variables, as well as direct forest height measurements.

- Feature Selection: From an initial set of 154 variables, 34 of the most predictive features are selected. These typically include elevation, vegetation indices (e.g., NDVI, EVI, LAI), and forest height metrics (e.g., RH100, RH98, RH95).

- Model Training and Validation: A RF regression model is trained to predict AGB using the selected features. The model is validated by holding out a portion of the reference data (e.g., from GEDI), ensuring that the performance metrics (R-squared and RMSE) reported on this validation set reflect the model's generalizability.

Workflow and Architectural Diagrams

Random Forest for Ecological Data Analysis

Diagram Title: RF for Ecological Data Analysis

Deep Neural Network for Bio-Logger Data

Diagram Title: DNN for Bio-Logger Data

Hybrid fDNN Architecture for Sparse Data

Diagram Title: Hybrid fDNN Model Architecture

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Tools for Machine Learning in Bio-Logging

| Tool / Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Google Earth Engine (GEE) [33] | Cloud Computing Platform | Provides access to massive satellite data catalogs and high-performance processing for large-scale ecological analysis. | Fusing Sentinel-1, Sentinel-2, and GEDI data for forest biomass estimation. |

| Bio-logger Ethogram Benchmark (BEBE) [31] | Benchmark Dataset | A public benchmark of diverse, annotated bio-logger data to standardize the evaluation of behavior classification models. | Comparing the performance of RF and DNN models across multiple species and sensors. |

| Animal-Borne Tags (Bio-loggers) [31] | Data Collection Hardware | Miniaturized sensors (accelerometer, gyroscope, GPS, etc.) attached to animals to record kinematic and environmental data. | Collecting tri-axial accelerometer data for classifying fine-scale behaviors like foraging and resting. |

| Self-Supervised Pre-training [31] | Machine Learning Technique | Leveraging large, unlabeled datasets to train a model's initial feature extractor, improving performance on downstream tasks with limited labels. | Fine-tuning a DNN pre-trained on human accelerometer data for animal behavior classification. |

| Forest fDNN Model [34] | Hybrid ML Algorithm | Combines a Random Forest as a sparse feature detector with a DNN for final prediction, ideal for data with many features and few samples (n << p). | Classifying disease outcomes from high-dimensional gene expression data. |

Design of Experiments (DOE) for Analytical Method Development and Characterization

Design of Experiments (DOE) is a structured, statistical approach for planning, conducting, and analyzing controlled tests to determine the relationship between factors affecting a process and its output [36]. In the pharmaceutical industry, DOE has become a cornerstone of Analytical Quality by Design (AQbD), a systematic framework for developing robust and reliable analytical methods [37]. Unlike the traditional One-Factor-at-a-Time (OFAT) approach, which is inefficient and fails to identify interactions between variables, DOE allows scientists to simultaneously investigate multiple factors and their interactions, leading to deeper process understanding and more robust outcomes [36] [38]. This guide compares the application of various DOE methodologies in analytical method development, providing a framework for their evaluation within emerging fields such as the statistical validation of bio-logging sensor data.

Core Principles and Terminology of DOE

To effectively utilize DOE, understanding its core components is essential. The power of DOE lies in its ability to uncover complex relationships that are impossible to detect using OFAT.

- Factors and Levels: Factors are the independent, controllable variables in an experiment (e.g., column temperature, pH, flow rate). Each factor is tested at different "levels"—the specific settings or values (e.g., a low temperature of 25°C and a high temperature of 40°C) [36].

- Responses: Responses are the dependent variables—the measured results or outputs (e.g., peak area, retention time, separation efficiency) [36].

- Interactions: An interaction occurs when the effect of one factor on the response depends on the level of another factor. Detecting these interactions is a key advantage of DOE, as they are often hidden causes of method instability [36].

- Main Effects: The main effect of a factor is the average change in the response caused by moving that factor from one level to another [36].

Comparison of Common DOE Designs

Selecting the appropriate experimental design is critical and depends on the number of factors and the specific objectives of the study, such as screening or optimization. The following table summarizes the characteristics of common DOE designs.

Table 1: Comparison of Common DOE Designs for Analytical Method Development

| Design Type | Primary Objective | Typical Number of Experiments | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Factorial [36] | Investigation of all main effects and interactions for a small number of factors. | (2^k) (for k factors at 2 levels) | Identifies all interaction effects between factors. | Number of runs grows exponentially; impractical for >5 factors. |

| Fractional Factorial [36] [37] | Screening a large number of factors to identify the most significant ones. | (2^{k-p}) (a fraction of full factorial) | Highly efficient; significantly reduces the number of experiments. | Interactions are aliased (confounded) with other effects. |

| Plackett-Burman [39] [36] [37] | Screening many factors with a very minimal number of runs. | Multiple of 4 (e.g., 12 runs for 11 factors) | Extreme efficiency for evaluating a high number of factors. | Used only to study main effects, not interactions. |

| Response Surface Methodology (RSM) - Central Composite Design (CCD) [36] [38] | Modeling and optimizing a process after key factors are identified. | Varies (e.g., CCD for 3 factors requires ~16 runs) | Maps a full response surface; finds optimal factor settings. | Requires more runs than screening designs. |

| Taguchi Arrays (e.g., L12) [39] [40] | Robustness testing, often in engineering applications. | Varies by array (e.g., L12 has 12 runs) | Saturated designs that minimize trials; balanced to estimate main effects. | Complex aliasing of interactions; controversial in some statistical circles. |

Application of DOE in the Method Development Lifecycle

The AQbD framework applies DOE at distinct stages of the analytical method lifecycle, each with a specific objective [37]. The following workflow illustrates a typical, iterative DOE process for method development and characterization.

Method Optimization

- Objective: To identify critical analytical parameters, establish their set points, and define operating ranges that ensure acceptable method performance [37].

- Protocol: A multi-factorial experiment is designed where key method parameters (factors) are varied across a predefined range (levels). Responses related to method accuracy, precision, and selectivity are measured. The data is analyzed to build a model that predicts performance and identifies the optimal combination of factor levels [36] [37].

Robustness Testing

- Objective: To evaluate the method's resilience to small, deliberate variations in its controlled parameters, demonstrating that it remains unaffected by normal operational fluctuations [37].

- Protocol: Using a fractional factorial or Plackett-Burman design, factors such as column temperature, mobile phase pH, or flow rate are varied around their set points within a narrow, expected range. The analysis confirms that all measured responses remain within acceptance criteria throughout this "design space" [39] [37].

Ruggedness Testing

- Objective: To assess the method's performance against uncontrolled, real-world variations, such as different analysts, instruments, reagent lots, or laboratories [37].

- Protocol: This study treats factors as "random factors," where the selected levels (e.g., three different analysts) represent a larger population. The goal is to estimate the magnitude of variation (variance) introduced by each noise factor, providing data for assessing intermediate precision and reproducibility [37].

Advanced DOE Strategies: Lifecycle and Integrated Approaches

To enhance efficiency across long development timelines, advanced strategies like Lifecycle DOE (LDoE) have been proposed. The LDoE approach involves starting with an initial optimal design (e.g., a D-optimal design) and systematically augmenting it with new experiments as development progresses [38]. This iterative cycle of design augmentation, model analysis, and refinement allows for flexible adaptation and consolidates all data into a single, comprehensive model. This method helps in identifying potentially critical process parameters early and can even support a Process Characterization Study (PCS) using development data [38]. Similarly, the Integrated Process Model (IPM) concept combines models from several unit operations to assess the impact of process parameters across the entire bioprocess [38].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key materials and solutions frequently employed in analytical method development experiments, particularly in a biopharmaceutical context.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Analytical Method Development

| Item / Solution | Function in Experiment | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Mobile Phase Components | Liquid carrier for chromatographic separation. | Factor in robustness studies; pH and buffer concentration are often critical parameters [36]. |

| Chromatographic Columns | Stationary phase for analyte separation. | Column temperature and supplier (different lot/brand) can be factors in ruggedness studies [37]. |

| Critical Reagents | Components for sample preparation or reaction (e.g., enzymes, derivatization agents). | Different reagent lots are studied as "noise factors" in ruggedness testing to assess variability [37]. |

| Reference Standards | Provides the known reference for quantifying accuracy and systematic error. | Correctness is vital for comparison studies; traceability to definitive standards is ideal [41]. |

| Patient/Process Samples | Real-world specimens used for method comparison. | Should cover the entire working range and represent expected sample matrices [41]. |

Cross-Disciplinary Insights: Parallels in Bio-Logging Sensor Validation

The principles of statistical design and validation are transferable across disciplines. The field of bio-logging—which uses animal-borne sensors to collect data on movement, physiology, and the environment—faces similar challenges in ensuring data validity and optimizing resource-limited operations [11] [2]. While not a direct comparison, the methodologies offer valuable parallels:

- Resource Optimization: Just as DOE optimizes laboratory resource use, AI-assisted bio-loggers use low-cost sensors (e.g., accelerometers) to trigger resource-intensive sensors (e.g., video cameras), dramatically extending runtime and precision in capturing target behaviors [42]. This is analogous to using a screening DOE to focus later, more intensive, optimization studies.

- Data Standardization and Validation: The "Biologging intelligent Platform (BiP)" emphasizes standardized data and metadata formats to ensure data quality, reproducibility, and secondary usability [2]. This aligns with the rigorous documentation and validation requirements in pharmaceutical AQbD, underscoring the universal need for structured data practices in scientific research.

- Model-Based Understanding: The proposed LDoE approach in bioprocessing [38] shares a conceptual foundation with efforts in biologging to link sensor data to fundamental biological parameters (e.g., energy expenditure, mortality) [11]. Both seek to build predictive models from multi-factorial data to understand complex systems.

Design of Experiments provides an indispensable statistical framework for developing and characterizing robust, reliable, and transferable analytical methods. Moving from OFAT to a structured DOE approach, as mandated by Quality by Design initiatives, yields profound benefits in efficiency, product quality, and regulatory compliance [36] [37] [38]. The comparison of various designs—from fractional factorials for screening to RSM for optimization—provides scientists with a versatile toolkit. Furthermore, the emerging paradigm of Lifecycle DOE promises a more holistic and efficient integration of knowledge across the entire development process. The parallels drawn with bio-logging sensor validation highlight the universal applicability of sound statistical design principles, suggesting that a DOE-based framework could significantly enhance the rigor and efficiency of data validation in that emerging field.

The expansion of bio-logging technologies has created new opportunities for studying animal behavior, physiology, and ecology in natural environments. These animal-borne data loggers collect vast amounts of raw sensor data, including acceleration, location, depth, and physiological parameters. However, a significant challenge remains in transforming this raw data into biologically meaningful insights through robust statistical validation methods. This process requires careful consideration of data collection strategies, analytical pipelines, and validation frameworks to ensure ecological conclusions are based on reliable evidence.

The field currently grapples with balancing resource constraints against data quality needs. Bio-loggers face strict mass and energy limitations to avoid influencing natural animal behavior, particularly for smaller species where loggers are typically limited to 3-5% of body mass [14]. These constraints necessitate efficient data collection strategies and sophisticated analytical approaches to extract maximum biological insight from limited resources, driving innovation in both hardware and analytical methodologies.

Strategic Approaches to Data Acquisition

Bio-logging researchers employ several strategic approaches to overcome the inherent limitations of logger capacity:

Sampling Methods: Synchronous sampling collects data at fixed intervals, while asynchronous sampling triggers recording only when sensors detect activity of interest, conserving resources during inactivity [14]. Asynchronous methods increase the likelihood of capturing desired movements while utilizing storage and energy more efficiently, making them particularly valuable for studying sporadic behaviors.