Spatially Explicit Land Use Optimization for Enhanced Ecosystem Services: From Deep Learning Surrogates to Multi-Scenario Planning

This article synthesizes cutting-edge methodologies and applications in spatially explicit land use optimization to enhance ecosystem services (ES).

Spatially Explicit Land Use Optimization for Enhanced Ecosystem Services: From Deep Learning Surrogates to Multi-Scenario Planning

Abstract

This article synthesizes cutting-edge methodologies and applications in spatially explicit land use optimization to enhance ecosystem services (ES). It explores the foundational trade-offs and synergies between multiple ES, such as carbon storage, water conservation, and habitat quality. The content delves into advanced computational frameworks, including deep learning surrogates and multi-objective evolutionary algorithms, that overcome traditional modeling limitations. It further examines optimization challenges and solutions across diverse ecological contexts, from urban green infrastructure to fragile drylands. Finally, the article provides a comparative analysis of validation techniques and scenario outcomes, offering researchers and land managers a comprehensive guide for integrating spatial optimization into sustainable landscape planning and policy development.

Understanding Ecosystem Service Trade-offs and Spatiotemporal Dynamics

Defining Spatially Explicit Optimization in Land Use Planning

Definition and Conceptual Framework

Spatially Explicit Optimization is an advanced computational approach in land use planning that identifies the optimal geographic allocation of land use types to maximize or minimize specific objectives, while simultaneously accounting for spatial configuration, neighborhood effects, and trade-offs between competing goals. Unlike traditional planning methods that might determine only the quantity of different land types needed, spatially explicit optimization specifies precisely where those land uses should be located to achieve optimal outcomes, recognizing that the spatial arrangement itself fundamentally influences ecosystem functionality and service provision [1] [2].

This methodology is fundamentally grounded in the ecosystem service cascade model, which links ecological structures and processes to the benefits humans derive from ecosystems [2]. Within land use planning, it operates through several interconnected theoretical pillars:

- Spatial Dependency: The ecosystem services provided by a land unit depend not only on its own characteristics but also on the land use types and biophysical properties of surrounding areas [1]. For instance, the cooling effect of an urban forest patch is influenced by adjacent impervious surfaces and the connectivity to other green spaces.

- Multi-Objective Trade-offs: Planning typically involves multiple, often conflicting objectives. Spatially explicit optimization makes these trade-offs explicit, enabling planners to identify solutions that offer the best possible compromises among competing goals like agricultural production, carbon storage, and habitat conservation [1] [3].

- Multifunctionality: A core principle of Green Infrastructure (GI) planning, multifunctionality seeks to design landscapes that provide multiple ecosystem services simultaneously, thereby using limited space more efficiently [2].

Key Methodological Approaches

Spatially explicit optimization employs a suite of integrated models and algorithms to resolve complex land use allocation problems. The following table summarizes the core methodological components commonly used in this field.

Table 1: Core Methodological Components of Spatially Explicit Optimization

| Component Type | Primary Function | Specific Tools & Algorithms |

|---|---|---|

| Ecosystem Service Assessment Models | Quantify the provision of ecosystem services based on land use/cover and biophysical data. | InVEST (Integrated Valuation of Ecosystem Services and Trade-offs) [1] [2] [4] |

| Land Use Simulation Models | Project future land use changes under different scenarios. | PLUS (Patch-generating Land Use Simulation) model [5] [4] [6] |

| Optimization Algorithms | Search for the optimal allocation of land uses to meet multiple objectives. | NSGA-II (Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm-II) [2], Linear Programming [1] |

| Surrogate Models | Approximate complex, computationally expensive models to enable faster iterative optimization. | Deep Learning models (UNet, Attention UNet) [1] |

Integrated Modeling Workflow

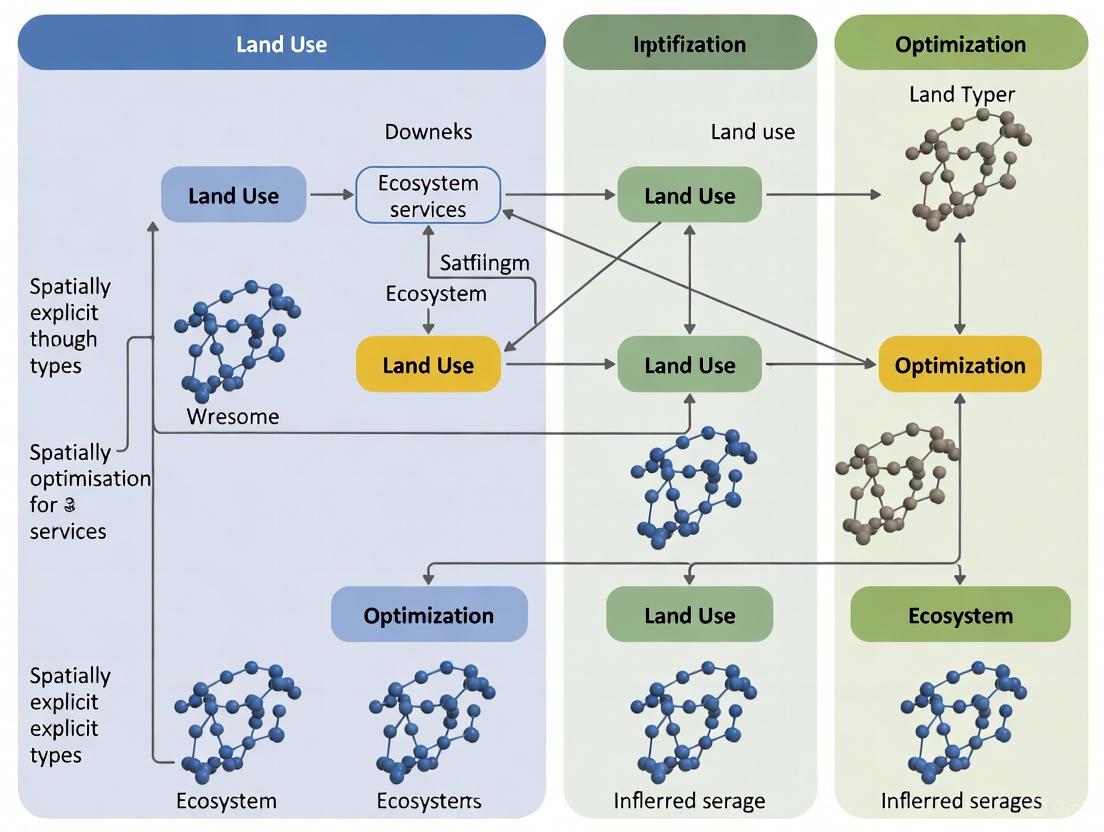

A standard workflow integrates these components, as illustrated in the following protocol diagram.

Diagram 1: Spatially Explicit Optimization Core Workflow

Deep Learning Surrogate-Assisted Optimization

A cutting-edge advancement involves using deep learning surrogates to overcome the high computational cost of repeatedly running models like InVEST within an optimization loop [1]. The detailed protocol for this approach is as follows:

Protocol 1: Deep Learning Surrogate Model Development and Application

- Purpose: To drastically reduce computation time for spatial optimization while maintaining high predictive accuracy for ecosystem services.

- Experimental Workflow:

Diagram 2: Deep Learning Surrogate Protocol

- Procedural Steps:

- Data Generation: Create a large and diverse dataset of land use and land cover (LULC) configurations. For each configuration, run the high-fidelity InVEST model to generate "ground truth" maps for target ecosystem services (e.g., habitat quality, carbon storage, urban cooling) [1].

- Model Training: Train a deep learning model, such as a UNet or Attention UNet, on the generated dataset. The model learns to perform image-to-image translation, taking a LULC map as input and predicting the corresponding ES maps as output. The Attention UNet is particularly effective at capturing long-range spatial dependencies [1].

- Model Validation: Rigorously test the trained surrogate model on a held-out dataset not seen during training. Evaluate performance using metrics like R² (coefficient of determination) and visual inspection of predicted vs. actual ES maps. Studies have achieved R² > 0.9 for services like habitat quality and urban heat mitigation [1].

- Optimization Execution: Embed the validated surrogate model into a multi-objective evolutionary algorithm (e.g., NSGA-II). The algorithm can now rapidly evaluate the fitness of thousands of candidate land use plans by using the fast DL surrogate instead of the slow InVEST model, cutting optimization time by over 95% while achieving comparable results [1].

Application Notes and Performance Data

Case Study Performance and Outcomes

The following table synthesizes quantitative results from real-world applications of spatially explicit optimization, demonstrating its impact across different contexts.

Table 2: Documented Performance and Outcomes of Spatially Explicit Optimization

| Case Study / Focus | Key Optimization Objectives | Tools & Models Used | Reported Outcomes & Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Urban Green Infrastructure, Baltimore [1] | Maximize habitat quality, urban cooling, and nature access on vacant lots. | InVEST, UNet/Attention UNet surrogates, Multi-objective evolutionary algorithm. | 95.5% reduction in computation time using surrogates while achieving R² > 0.9 for ES predictions. Produced a Pareto front of 50 optimal GI allocation schemes. |

| Green Infrastructure, Wuhu City [2] | Maximize crop production, habitat quality, and runoff reduction. | InVEST, NSGA-II algorithm. | Identified 50 Pareto-optimal solutions, revealing non-linear trade-offs between crop production and habitat quality. Model convergence confirmed via hypervolume metric. |

| Land Use Structure, Dongting Lake [5] | Realize ecological and socio-economic benefits under ecosystem service constraints. | InVEST, Interval uncertainty optimization, PLUS model. | Optimized economic benefits between [15622.72, 19150.50] × 10⁸ CNY. Ecosystem service values and pollution levels showed better performance than status quo. |

| Carbon Storage, Jinan City [6] | Understand and plan carbon storage across urban-rural gradients. | PLEL-InVEST-PLUS (PGIP) Framework. | Forecasted under spatial planning scenario: 14.86 km² increase in high-value CS clusters, 3.99 km² decrease in low-value clusters compared to unconstrained development. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Spatially Explicit Optimization

| Item / Tool | Category | Primary Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| InVEST Model Suite [1] [2] | Ecosystem Service Quantification Software | A core set of spatially explicit models that map and value ecosystem services based on LULC and biophysical input data. |

| PLUS Model [5] [4] | Land Use Simulation Software | Simulates future patch-level land use changes by integrating driving factors and spatial planning constraints. |

| NSGA-II Algorithm [2] | Optimization Algorithm | A powerful multi-objective genetic algorithm used to find a Pareto-optimal set of non-dominated solutions. |

| UNet & Attention UNet [1] | Deep Learning Architecture | Serves as a spatially aware surrogate model to approximate complex simulations, dramatically speeding up optimization. |

| Geographic Information System (GIS) | Data Platform | The foundational platform for managing, analyzing, and visualizing all spatial data throughout the optimization process. |

Analysis of Trade-offs and Stakeholder Integration

A critical output of spatially explicit multi-objective optimization is the Pareto front, which represents the set of optimal solutions where improving one objective (e.g., crop production) necessitates worsening another (e.g., habitat quality) [2]. Analyzing this front reveals complex, often non-linear relationships between ecosystem services, providing crucial insights for planners.

Furthermore, the optimization process can incorporate stakeholder perspectives to ensure practical relevance. By using methods like the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), different weights can be assigned to ecosystem services based on the preferences of various stakeholder groups (e.g., farmers, conservationists, policymakers) [3]. This allows for the generation of optimized scenarios that reflect diverse priorities, such as "sustainably intensify," "increase landscape multifunctionality," or "restore ecological integrity," thereby bridging the gap between technical optimization and societal values [3].

The Critical Link Between Land Use Intensity and Ecosystem Service Provision

Land Use Intensity (LUI) serves as a critical indicator for assessing the degree of human modification and disturbance on natural landscapes. Concurrently, Ecosystem Services (ESs) represent the multitude of benefits that humans derive, directly or indirectly, from ecosystems [7]. These services encompass provisioning services (e.g., food supply), regulating services (e.g., water purification, climate regulation), supporting services, and cultural services [8]. The interplay between LUI and ES provision forms a fundamental nexus in land use planning and ecosystem management. As human activities intensify, changes in land use structure and state frequently lead to habitat fragmentation, altering ecosystem structure and function, and ultimately impacting biodiversity and the provision of ESs [7]. Understanding this relationship is therefore paramount for realizing scientific ecosystem management and achieving sustainable development goals [8] [9].

This document provides application notes and detailed protocols for researchers aiming to quantify this critical link within the context of spatially explicit land use optimization. The frameworks and methods outlined herein are designed to integrate ecological understanding with land management decision-making.

Quantitative Assessment Frameworks

A robust assessment requires the standardized quantification of both Land Use Intensity and Ecosystem Service Value. The following tables provide established frameworks for this purpose.

Table 1: Land Use Intensity (LUI) Classification and Weight Assignment

| Land Use Type | Intensity Class | Assigned Weight (Ci) | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Construction Land | Very High | 1.00 | Represents the maximum degree of anthropogenic alteration and impervious surface cover. |

| Cultivated Land | High | 0.65 | Signifies managed ecosystems with regular human intervention (e.g., fertilization, irrigation). |

| Garden Land | Medium | 0.45 | Indicates moderately intensive land management practices. |

| Grassland | Low | 0.30 | Represents ecosystems with lower human disturbance compared to cultivated lands. |

| Forest Land | Low | 0.30 | Characterized by minimal direct human management and high ecological value. |

| Water Bodies | Very Low | 0.05 | Represents natural aquatic ecosystems with minimal direct intensity pressure. |

| Unused Land | Very Low | 0.01 | Land with no discernible productive or transformative human use. |

Table 2: Ecosystem Service Value (ESV) Assessment Equivalents per Unit Area (yuan/ha/year)

| Service Category | Cultivated Land | Forest Land | Grassland | Water Bodies | Unused Land |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provisioning Services | |||||

| Food Production | 1.36 | 0.16 | 0.21 | 0.41 | 0.01 |

| Raw Material Production | 0.16 | 0.63 | 0.17 | 0.25 | 0.03 |

| Regulating Services | |||||

| Climate Regulation | 0.33 | 1.93 | 0.81 | 0.35 | 0.05 |

| Water Conservation | 0.17 | 1.93 | 0.81 | 19.29 | 0.05 |

| Waste Treatment | 0.11 | 0.63 | 0.27 | 7.18 | 0.11 |

| Supporting Services | |||||

| Soil Formation | 0.43 | 1.53 | 0.65 | 0.02 | 0.11 |

| Biodiversity | 0.16 | 1.93 | 0.82 | 1.59 | 0.14 |

| Cultural Services | |||||

| Aesthetic Landscape | 0.05 | 0.83 | 0.35 | 1.91 | 0.09 |

| Total ESV per Hectare | 2.77 | 9.57 | 4.09 | 31.00 | 0.59 |

Application Notes: Quantitative Assessment

- LUI Calculation: The comprehensive LUI index for a given area (e.g., a grid cell or administrative region) is calculated using the formula:

LUI = 100 × ∑(A_i × C_i), whereA_iis the area proportion of land use typei, andC_iis its assigned intensity weight [7]. A higher index indicates greater human pressure on the landscape. - ESV Calculation: The total ESV is calculated by multiplying the area of each land use type by its corresponding total value per hectare from Table 2 and summing the results:

Total ESV = ∑(Area_i × ESV_per_hectare_i)[10]. This approach allows for the spatial and temporal tracking of ESV changes in response to land use transformation. - Spatial Explicitness: For integration with spatially explicit optimization, these calculations should be performed at the finest possible resolution (e.g., 30m x 30m grid cells) to capture landscape heterogeneity and inform targeted management strategies [9].

Experimental Protocols for Investigating the LUI-ES Link

Protocol 1: Spatial-Temporal Assessment of LUI and ESV

Objective: To analyze the spatiotemporal evolution of Land Use Intensity and Ecosystem Service Value over a defined historical period.

Workflow:

Methodology:

- Data Collection & Preparation: Gather multi-temporal land use data (e.g., for 2000, 2010, 2020) from satellite imagery or land survey datasets. Acquire supporting data, including Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), Net Primary Productivity (NPP), Digital Elevation Model (DEM), climate data (precipitation, temperature), and socio-economic data (population density, GDP) [7] [10].

- Land Use Dynamics Analysis: Calculate the dynamic degree of single land use types using the formula:

K = (U2 - U1) / (U1 × (T2 - T1)) × 100%, whereU1andU2are the areas at the start and end of the study period, andT2-T1is the time interval [10]. Use a land use transfer matrix to quantify transitions between different types. - LUI and ESV Quantification: Apply the formulas and coefficients provided in Section 2 to calculate LUI and ESV for each spatial unit and time slice.

- Spatio-Temporal Analysis: Utilize Geo-information Tupu theory to create land use transformation maps [10]. Employ spatial autocorrelation models (e.g., Local Indicators of Spatial Association - LISA) to identify statistically significant hotspots (high-value clusters) and coldspots (low-value clusters) of ESV and LUI [7]. Analyze the bivariate spatial correlation between LUI and ESV to visualize areas of "High LUI - Low ESV" and "Low LUI - High ESV" aggregation.

Protocol 2: Scenario-Based Land Use Optimization and ESV Projection

Objective: To model future land use scenarios and simulate their impact on Ecosystem Service Value to inform sustainable land planning.

Workflow:

Methodology:

- Scenario Definition: Establish distinct future scenarios, such as:

- Natural Development (ND): Extends historical trends without policy intervention.

- Rapid Economic Development (RED): Prioritizes economic growth, allowing for construction land expansion.

- Ecological Land Protection (ELP): Focuses on protecting and restoring forests and grasslands.

- Sustainable Development (SD): A balanced approach seeking to harmonize economic and ecological objectives [9].

- Spatial Constraints: Incorporate legally binding spatial planning boundaries as constraints in the model. These include the Ecological Protection Redline (RLE), Permanent Basic Cropland (PBC), and the Boundary for Urban Development (BUD) [9].

- Land Use Optimization Simulation:

- Quantity Optimization: Use the Gray Multi-objective Optimization (GMOP) model to determine the optimal quantity of each land use type under the different scenario objectives and constraints [9].

- Spatial Allocation: Input the GMOP results into the Patch-generating Land Use Simulation (PLUS) model. The PLUS model uses a random forest algorithm to analyze the driving forces of land use change and an adaptive inertia competition mechanism to spatially allocate the future land use patch-by-patch at a fine scale (e.g., 30m) [9].

- ESV Estimation and Evaluation: Calculate the projected ESV for each optimized future land use scenario using the methods in Section 2. Compare the outcomes to identify the scenario that best enhances ecosystem services while meeting development needs.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for LUI-ES Analysis

| Category / Tool Name | Function / Purpose | Key Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| InVEST Model Suite | A suite of spatially explicit models for mapping and valuing ecosystem services. Key models include: Seasonal Water Yield, Sediment Retention, Carbon Storage, and Habitat Quality. | Translates land use/cover maps and biophysical data into spatial estimates of ES supply. Essential for quantifying regulating and supporting services [7]. |

| PLUS Model | Patch-generating Land Use Simulation model for projecting future land use scenarios at a fine, patch-level resolution. | Used in conjunction with GMOP for spatial optimization. Superior to traditional CA models due to its LEAS and CARS mechanisms [9]. |

| Bayesian Belief Network (BBN) | A probabilistic graphical model that represents variables and their conditional dependencies. | Integrates ecological and socio-economic factors with expert knowledge to simulate processes and infer outcomes under various management scenarios [8]. |

| Spatial Autocorrelation Analysis (LISA) | Identifies significant spatial clusters (hotspots/coldspots) and outliers in the data. | Used to reveal the spatial aggregation patterns of LUI and ESV and their bivariate correlations (e.g., Low-High, High-Low) [7]. |

| R "kohonen" Package | Used for identifying Ecosystem Service Bundles—sets of ES that repeatedly appear together across the landscape. | Reduces complexity by grouping correlated ESs, allowing for the management of synergistic and trade-off relationships [7]. |

| ACT Rule & Contrast Checker | Ensures that all data visualizations, charts, and diagrams meet WCAG guidelines for color contrast. | Critical for creating accessible scientific communications that are legible to all audiences, including those with color vision deficiencies [11] [12]. |

Ecosystem services (ES) are the benefits that humans derive directly or indirectly from ecosystems, encompassing provisioning, regulating, supporting, and cultural services [8]. Spatially explicit mapping of these services has emerged as a critical methodology in land system science, enabling researchers, scientists, and policymakers to quantify, visualize, and optimize the distribution of benefits such as carbon storage, habitat quality, water yield, and sediment retention across landscapes. This approach is particularly valuable in the context of growing environmental challenges including climate change, biodiversity loss, and ecosystem degradation [13]. The integration of spatially explicit ES assessment into land use optimization provides a scientific basis for sustainable management, allowing for the identification of trade-offs and synergies between different services and facilitating informed decision-making for conservation and development planning [8] [13].

The theoretical foundation of this field bridges landscape ecology, geography, and sustainability science, operating on the principle that the spatial configuration of land use and land cover (LULC) fundamentally influences ecosystem structure, function, and, consequently, service provision [13]. Recent research paradigms have evolved from mere pattern description toward sustainable development and ecological restoration orientations, with the research framework transforming from "pattern to function to well-being" [13]. This progression reflects an increasing recognition that optimizing the spatial pattern of land use is essential for restoring ecosystem functions and achieving sustainable human-land relationships in an era of high-intensity human disturbance and rapid climate change.

Key Ecosystem Services: Quantitative Assessments and Methodologies

Carbon Storage

Carbon storage represents a critical regulating ecosystem service in climate change mitigation. Recent research indicates that the carbon sequestration potential from global ecosystem restoration may be more limited than previously estimated. A comprehensive 2025 model-based study found that the maximum carbon sequestration potential from restoring forest, shrubland, grassland, and wetland ecosystems through 2100 is approximately 96.9 gigatons of carbon (GtC), equivalent to just 17.6% of anthropogenic emissions to date, or a mere 3.7–12.0% when considering future emissions through 2100 [14]. This constrained potential underscores the importance of accurately quantifying existing carbon stocks and prioritizing their protection in land use optimization.

The distribution of carbon storage varies significantly across ecosystems. Studies in the Brazilian Pampa biome have demonstrated that high carbon stock values are predominantly associated with areas of native vegetation, emphasizing the conservation value of these ecosystems [15]. When evaluating carbon storage, it is essential to consider both aboveground and belowground carbon pools, particularly in open ecosystems like grasslands and savannahs where carbon is primarily stored belowground, potentially offering greater resilience to disturbances such as fire and drought [14].

Table 1: Carbon Storage Potential Across Major Ecosystem Types

| Ecosystem Type | Global Restoration Potential (Area) | Key Carbon Storage Characteristics | Notable Vulnerabilities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Forest | 11.66 million km² available for restoration [14] | Significant aboveground and belowground carbon stocks | Vulnerable to deforestation, fire, drought-induced mortality [14] |

| Grassland | 9.37 million km² available for restoration [14] | Predominantly belowground carbon storage; more secure from fire [14] | Threatened by afforestation programs and land conversion [14] |

| Shrubland | 4.91 million km² available for restoration [14] | Mixed aboveground and belowground carbon allocation | Often overlooked in tree-centric restoration models [14] |

| Wetland | 2.83 million km² available for restoration [14] | Significant carbon sequestration capacity, especially peatlands | Extensive drainage for agriculture reduces carbon storage [14] |

Habitat Quality

Habitat quality serves as a crucial indicator of biodiversity support capacity within ecosystems. It reflects the ability of an environment to provide suitable conditions for species persistence, taking into account habitat extent, connectivity, and the intensity of anthropogenic threats. The InVEST Habitat Quality model utilizes habitat quality and rarity as proxies to represent landscape biodiversity, estimating the extent of habitat and vegetation types across a landscape and their state of degradation [16]. This model combines LULC maps with data on threats to habitats and habitat response, enabling users to compare spatial patterns and identify areas where conservation will most benefit natural systems and protect threatened species [16].

Research in fragile ecosystems like Inner Mongolia has demonstrated significant declines in habitat quality associated with accelerated economic development and urbanization [8]. Similarly, studies in the Brazilian Pampa biome have revealed that despite large degraded areas, high habitat quality remains strongly associated with native vegetation across all studied watersheds [15]. These findings highlight the importance of preserving natural vegetation patches as core habitats and maintaining ecological connectivity in land use planning.

Table 2: Habitat Quality Assessment in Different Biomes

| Biome/Region | Habitat Quality Status | Primary Threats | Conservation Insights |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brazilian Pampa | High habitat quality associated with native vegetation [15] | Land use/cover changes, degradation [15] | Native vegetation crucial despite extensive degraded areas [15] |

| Inner Mongolia, China | Significant declines observed [8] | Accelerated economic development, urbanization, population expansion [8] | Sensitive to anthropogenic influence and climate fluctuation [8] |

| Global Drylands | Varies significantly with vegetation and climate conditions [8] | Climate change, unsustainable human activities [8] | Ecosystem services play critical roles in these fragile systems [8] |

Complementary Ecosystem Services

In addition to carbon storage and habitat quality, comprehensive land use optimization must consider several other critical ecosystem services:

- Water Yield: The supply of surface and groundwater for human use, which exhibits significant spatial imbalances across regions [8]. In dryland regions like Inner Mongolia, water yield provision has shown variability over time, reflecting changing precipitation patterns and water extraction [8].

- Sediment Retention: The capacity of ecosystems to prevent soil erosion and retain sediments. Studies in the Brazilian Pampa have identified high sediment retention values in areas with native vegetation [15]. The spatiotemporal evolution of this service must be considered in watershed management.

- Windbreak and Sand Fixing: Particularly important in arid and semi-arid regions, this service helps stabilize soils and prevent desertification. Research in Inner Mongolia has documented variations in this service over time [8].

Interactions Among Ecosystem Services: Trade-offs and Synergies

Understanding the complex interactions between multiple ecosystem services is fundamental to spatially explicit land use optimization. These relationships predominantly manifest as trade-offs and synergies, which vary significantly across both space and time [8]. Trade-offs occur when an increase in one service leads to a decrease in another, while synergies exist when two services change in the same direction [8]. For instance, enhancing provisioning ecosystem services (e.g., food production) often results in trade-offs with regulating services (e.g., carbon storage, habitat quality) [8].

Research in Inner Mongolia demonstrated significant spatial and temporal variations in relationships between paired ecosystem services [8]. These dynamic interactions are influenced by multiple factors including land use type, vegetation cover, and climate conditions [8]. The blind pursuit of particular ecosystem services without considering these trade-offs and synergies typically intensifies conflicts between services, ultimately leading to ecosystem degradation [8].

Figure 1: Ecosystem Service Interactions Framework

Experimental Protocols for Ecosystem Service Assessment

Protocol for Integrated Ecosystem Service Assessment

This protocol provides a standardized methodology for quantifying and mapping multiple ecosystem services to support spatially explicit land use optimization.

1. Study Area Delineation and Data Collection

- Define spatial boundaries (watershed, administrative unit, or ecological region)

- Collect multisource data including:

- Land use/land cover (LULC) maps for multiple time points

- Climate data (precipitation, temperature, evapotranspiration)

- Soil maps (type, texture, depth, organic matter)

- Topographic data (digital elevation models)

- Socioeconomic data (population density, economic indicators)

2. Ecosystem Service Quantification

- Apply integrated modeling approaches:

- Soil Retention: Utilize Revised Universal Soil Loss Equation (RUSLE) model [8]

- Carbon Storage: Apply InVEST Carbon Storage and Sequestration model [15]

- Habitat Quality: Implement InVEST Habitat Quality model [16] [8]

- Water Yield: Calculate using water balance approaches [8]

- Wind and Sand Control: Employ Revised Wind Erosion Equation (RWEQ) model [8]

3. Spatiotemporal Analysis

- Analyze ecosystem service dynamics across multiple time points (e.g., 2000, 2010, 2020) [8]

- Identify areas of ecosystem service degradation, stability, and improvement

- Map spatial patterns and identify service hotspots and coldspots [15]

4. Interaction Assessment

- Conduct correlation analysis between pairwise ecosystem services [8]

- Identify significant trade-offs and synergies using statistical methods

- Map spatial heterogeneity in ecosystem service relationships [8]

5. Scenario Simulation and Optimization

- Develop future land use scenarios based on different management priorities

- Simulate ecosystem service provision under each scenario

- Identify optimal spatial patterns using Bayesian Belief Networks (BBN) or other optimization models [8]

Protocol for Coastal Ecosystem Service Evaluation

For coastal ecosystems including tidal flats, wetlands, seaweed beds, and coral reefs, specialized evaluation methods are required:

1. Service Selection and Conceptual Model Development

- Select relevant coastal ecosystem services (food provision, coastal protection, water front use, sense of place, water quality regulation, biodiversity) [17]

- Create conceptual models linking services to environmental factors in natural and social systems [17]

2. Reference Site Establishment

- Identify natural reference sites within the same water area for comparison [17]

- Establish baseline values for ecosystem service provision

3. Quantitative Assessment

- Apply the Coastal Ecosystem Services Index (CEI) method [17]

- Score services against reference points to evaluate degree of achievement

- Incorporate sustainability considerations through trend analysis [17]

4. Composite Evaluation

- Calculate weighted composite scores based on stakeholder input

- Identify environmental factors requiring management intervention [17]

Figure 2: Ecosystem Service Assessment Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for Ecosystem Service Research

| Tool/Model | Primary Function | Application Context | Key Outputs |

|---|---|---|---|

| InVEST Suite | Models multiple ecosystem services using LULC and biophysical data [16] [15] | Regional to landscape-scale assessment of habitat quality, carbon storage, water yield [16] [15] | Spatial maps of service distribution, quantitative values [16] |

| RUSLE Model | Quantifies soil erosion and sediment retention capacity [8] | Watershed management, soil conservation planning [8] | Soil loss estimates, sediment retention maps [8] |

| RWEQ Model | Assesses wind erosion and sand fixation services [8] | Dryland ecosystems, desertification control [8] | Wind erosion rates, sand fixation capacity [8] |

| Bayesian Belief Networks (BBN) | Models complex relationships and uncertainties in ES interactions [8] | Scenario analysis, trade-off evaluation, decision support [8] | Probability distributions, scenario outcomes, optimization pathways [8] |

| SWAT Model | Simulates hydrological processes and water quality [18] | Watershed-scale water resource management [18] | Water yield, nutrient cycling, sediment transport [18] |

Applications in Land Use Optimization and Ecosystem Management

The integration of spatially explicit ecosystem service assessment into land use optimization has yielded significant insights for sustainable landscape management. Research in Inner Mongolia demonstrated how Bayesian Belief Networks can identify spatially explicit priority areas for optimization under different scenarios involving trade-offs and synergies between ecosystem services [8]. This approach enables decision-makers to target interventions to areas where they will yield the greatest benefits across multiple services.

In the Brazilian Pampa biome, the identification of ecosystem service hotspots through InVEST models provided a simplified and useful tool for guiding conservation policies and sustainable land management [15]. The study revealed that despite large degraded areas, high habitat quality persisted in native vegetation patches, highlighting their strategic importance for conservation [15]. Similarly, research on global ecosystem restoration potential emphasized that restoration should be pursued primarily for biodiversity conservation, livelihood support, and ecosystem service resilience, rather than for climate mitigation alone [14].

The conceptual framework of "element sets–network structure–system functions–human well-being" integrates landscape ecology and ecosystem service flows, providing a comprehensive approach for understanding how spatial patterns of land use ultimately affect human welfare [13]. This framework emphasizes that sustainable land management requires maintaining the ecological structures and processes that underpin ecosystem service provision while balancing diverse human needs.

Spatially explicit mapping of key ecosystem services from carbon storage to habitat quality provides an indispensable foundation for sustainable land use optimization in an era of rapid global change. The methodologies and protocols outlined in this application note enable researchers and practitioners to quantify, visualize, and analyze the distribution of ecosystem services across landscapes, identify critical trade-offs and synergies, and develop optimized land management strategies that maximize ecological and human benefits.

Future research directions should focus on enhancing theoretical frameworks, improving understanding of spatiotemporal mechanisms, identifying critical transformation thresholds, and reducing uncertainties in spatial simulation and prediction [13]. Additionally, there is a pressing need to develop more integrated approaches that consider the dynamic impacts of climate change on ecosystem service provision and the feedback effects of human adaptation responses [13]. As the field advances, the integration of ecosystem service concepts into territorial spatial planning and land management decisions will be crucial for building resilient landscapes capable of supporting both biodiversity and human well-being in a changing world.

Analyzing Trade-offs and Synergies in Multi-Service Environments

In spatially explicit land use optimization research, analyzing the complex interactions between multiple ecosystem services (ESs) is fundamental for sustainable environmental management. Trade-offs occur when an increase in one ecosystem service leads to a decrease in another, representing a "win-lose" scenario. Conversely, synergies exist when two or more services simultaneously increase or decrease, creating a "win-win" or "lose-lose" relationship [8] [19]. These interactions arise because land use decisions that prioritize one service often directly or indirectly affect the provision of others [8]. Understanding these dynamics is particularly crucial in ecologically fragile regions (EFRs), where improper management can lead to severe ecosystem degradation [8].

The spatial and temporal dimensions of these relationships add layers of complexity. Trade-offs and synergies can vary significantly across different spatial scales—what appears as a synergy at a regional scale may manifest as a trade-off at the local scale [20]. For instance, research in Suzhou City demonstrated that the relationship between water production and net primary productivity shifted from synergy to trade-off when transitioning from the autonomous region scale to the county scale [19]. Temporally, these relationships are not static; they can strengthen, weaken, or even reverse direction over time due to both natural processes and human interventions [20]. This multi-scale, dynamic nature of ES interactions presents a substantial challenge for land use planners and policymakers aiming to optimize multiple ESs simultaneously.

Quantitative Assessment of ES Interactions

Statistical Approaches for Relationship Analysis

Researchers employ various quantitative methods to detect and measure trade-offs and synergies between ecosystem services. Correlation analysis serves as a foundational approach, with the Pearson correlation coefficient commonly used to measure the strength and direction of linear relationships between paired ESs [21] [22]. A study in Henan Province utilized this method to identify significant synergies between water conservation-water yield and carbon storage-habitat quality pairs [22]. For non-linear relationships, spatial overlay analysis combines GIS mapping with statistical approaches to identify areas where multiple ESs co-vary positively (synergies) or negatively (trade-offs) [22].

More advanced techniques include geographically weighted regression (GWR), which accounts for spatial non-stationarity in relationships, revealing how trade-offs/synergies vary across a landscape [23]. The difference comparison method enables analysis across different spatial scales, allowing researchers to compare interaction relationships at grid, county, and regional levels [20]. In Inner Mongolia, researchers combined these approaches to discover that the same two ESs could exhibit different relationships in different regions, largely influenced by local land use types, vegetation, and climate conditions [8].

Quantitative Models for Relationship Mapping

Table 1: Modeling Approaches for Analyzing ES Trade-offs and Synergies

| Model Type | Primary Function | Key Applications | Data Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| InVEST Model | Quantifies biophysical and economic values of multiple ESs | Spatial mapping of ES provision; baseline assessment | Land use/cover data, DEM, precipitation, soil data |

| Bayesian Belief Network (BBN) | Models probabilistic relationships between drivers and ES outcomes | Simulating ES responses under different management scenarios | Expert knowledge, empirical data, driver variables |

| PLUS Model | Simulates land use change under multiple scenarios | Projecting future ES dynamics under different development pathways | Historical land use data, driving factors, development constraints |

| Self-Organizing Maps (SOM) | Identifies ecosystem service bundles through unsupervised clustering | Regional zoning based on dominant ES interactions | Multiple ES layers, spatial data |

Advanced modeling approaches enable more sophisticated analysis of ES interactions. The InVEST (Integrated Valuation of Ecosystem Services and Tradeoffs) model has become a widely used tool for quantifying multiple ESs, including water yield, carbon storage, soil conservation, and habitat quality [8] [20] [23]. Its outputs provide the foundational data for subsequent trade-off analysis. Bayesian Belief Networks (BBNs) offer particular value for modeling the complex causal relationships between drivers and ES outcomes, integrating both quantitative data and expert knowledge to simulate how ESs might respond to different management interventions [8].

For forward-looking analysis, land use simulation models like the PLUS (Patch-generating Land Use Simulation) model can project how ES interactions might evolve under different future scenarios [23] [22]. These models are especially powerful when combined with self-organizing maps (SOM) to identify "ecosystem service bundles"—recurring groups of ESs that consistently appear together across a landscape [23]. This bundle approach facilitates the zoning of territories based on dominant ES interactions, enabling more targeted management strategies.

Experimental Protocols for ES Assessment

Protocol 1: Multi-Temporal ES Quantification and Interaction Analysis

This protocol provides a standardized methodology for quantifying multiple ecosystem services and analyzing their interactions across temporal scales.

1.1 Study Area Definition and Spatial Delineation

- Define study area boundaries using appropriate administrative or biophysical units

- Collect baseline data on key characteristics: climate, topography, soil types, land use/cover, and socio-economic factors

- Divide the study area into meaningful analytical units (grid cells, watersheds, or administrative units)

1.2 Data Collection and Preparation

- Gather time-series data for at least two time points (e.g., 2000, 2010, 2020) for the following parameters [8] [20]:

- Land use/land cover (LULC) data from remote sensing or national databases

- Digital Elevation Model (DEM) for topographic analysis

- Meteorological data (precipitation, temperature, potential evapotranspiration)

- Soil data (type, texture, depth, organic matter content)

- Socio-economic data (population, GDP, development indices) where relevant

- Process all data to a consistent spatial resolution and coordinate system

1.3 Ecosystem Service Quantification

- Apply appropriate models to quantify key ESs:

- Water Yield: Use the InVEST Annual Water Yield module with inputs of precipitation, land use, soil depth, and plant available water content [20]

- Carbon Storage: Apply the InVEST Carbon Storage module with land use data and carbon pool estimates for four pools (aboveground, belowground, soil, dead organic matter) [8]

- Soil Conservation: Implement the Revised Universal Soil Loss Equation (RUSLE) within GIS environment to estimate soil retention [8] [19]

- Habitat Quality: Utilize the InVEST Habitat Quality module with land use data and threat sources [8]

- Sand Fixation: Apply the Revised Wind Erosion Equation (RWEQ) in arid regions [8]

1.4 Trade-off and Synergy Analysis

- Calculate correlation coefficients (Pearson or Spearman) between all ES pairs for each time period [22]

- Perform spatial overlay analysis to identify areas of high ES supply (synergies) and areas where one ES is high while another is low (trade-offs)

- Use difference comparison method to analyze how relationships change over time [20]

- Validate findings with local ecological knowledge and field data where available

1.5 Interpretation and Visualization

- Create spatial maps showing ES distributions and interaction hotspots

- Generate scatter plots with regression lines to visualize relationships between ES pairs

- Develop transition matrices showing how ES relationships have changed over time

Protocol 2: Multi-Scale ES Interaction Assessment

This protocol addresses the critical issue of scale in ES interactions, enabling researchers to analyze how relationships change across different spatial scales.

2.1 Multi-Scale Framework Design

- Define at least three nested spatial scales for analysis (e.g., grid, watershed, regional scales)

- For grid-scale analysis, create multiple resolutions (e.g., 2km, 5km, 10km) to assess scale effects [20]

- Ensure consistent ES quantification methods across all scales

2.2 Scale-Specific ES Calculation

- Calculate ES values for each defined spatial unit using consistent methodologies

- Aggregate finer-scale data to coarser scales using appropriate statistical methods (mean, median, or sum depending on the ES)

- Maintain metadata on scale transformations for interpretation

2.3 Cross-Scale Interaction Analysis

- Perform correlation analysis between ES pairs at each spatial scale

- Compare the strength and direction of relationships across scales

- Identify scale thresholds where relationships change significantly

- Use geographical detector model to quantify the power of scale determinants [20]

2.4 Cold/Hot Spot Analysis

- Apply Getis-Ord Gi* statistic or similar spatial clustering technique to identify significant spatial clusters of high values (hot spots) and low values (cold spots) for each ES [20]

- Overlay hot/cold spot maps for different ESs to identify spatial concordance (synergies) and discordance (trade-offs)

- Analyze how clustering patterns change across scales

2.5 Scale-Explicit Management Recommendations

- Develop scale-specific management recommendations based on identified interactions

- Identify priority areas for intervention at each scale

- Formulate cross-scale governance strategies that address interactions at multiple levels

Protocol 3: Scenario-Based Analysis for Land Use Optimization

This protocol enables researchers and planners to project future ES interactions under different land use scenarios and identify optimal spatial configurations.

3.1 Scenario Definition

- Define at least three alternative development scenarios:

- Ecological Protection (EP) Priority: Maximizes ecological benefits with strict conservation constraints [23]

- Economic Development Priority: Maximizes economic returns with minimal ecological constraints

- Balanced Development: Seeks to optimize both ecological and economic objectives

- Establish scenario-specific constraints and objectives based on stakeholder input

3.2 Land Use Simulation

- Utilize the PLUS model or similar land use simulation platform to project future land use patterns under each scenario [23] [22]

- Incorporate ecological security patterns (ESPs) as "ecological redlines" in the EP scenario to restrict development in critical areas [23]

- Calibrate the model using historical land use change data

- Validate model accuracy with actual land use data

3.3 Future ES Projection

- Apply ES quantification models (InVEST, RUSLE, etc.) to the simulated land use maps for each scenario

- Calculate ES values for the future time period (e.g., 2030, 2035)

- Compare ES provision across scenarios to identify trade-offs

3.4 Spatial Optimization

- Identify optimal spatial configurations that maximize desired ES bundles while minimizing trade-offs

- Use multi-objective optimization algorithms to identify Pareto-optimal solutions

- Map priority areas for conservation, restoration, and development

3.5 Policy Integration

- Translate optimization results into actionable land use zoning recommendations

- Develop implementation pathways with appropriate policy instruments

- Identify potential compensation mechanisms for areas bearing conservation costs

Table 2: Essential Tools and Models for ES Trade-off Analysis

| Tool/Model | Primary Function | Application Context | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| InVEST Suite | Spatially explicit ES quantification | Baseline assessment of multiple ES; mapping service distributions | [8] [20] [23] |

| RUSLE | Soil erosion and conservation estimation | Calculating soil retention capacity; identifying erosion hotspots | [8] [19] |

| RWEQ | Wind erosion modeling | Sand fixation assessment in arid and semi-arid regions | [8] |

| PLUS Model | Land use simulation under multiple scenarios | Projecting future land use patterns; scenario analysis | [23] [22] |

| Bayesian Belief Networks | Modeling probabilistic relationships | Understanding driver-ES relationships; management scenario testing | [8] |

| Geographical Detector | Identifying driving factors | Analyzing influence of natural and anthropogenic factors on ES | [23] [22] |

Data Presentation and Analysis Framework

Quantitative Relationships in ES Interactions

Table 3: Documented Trade-offs and Synergies Across Multiple Studies

| Ecosystem Service Pair | Relationship Type | Context/Spatial Pattern | Study Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Water Yield - Carbon Storage | Trade-off dominant | Strong trade-off at 2km and 10km grid scales; varies by region | [20] |

| Carbon Storage - Habitat Quality | Significant synergy | Consistent positive correlation across multiple studies | [22] |

| Water Yield - Soil Conservation | Synergy dominant | Mainly synergistic with different spatial agglomeration patterns | [20] |

| Flood Regulation - Other Services | Trade-off | Strong trade-off with water conservation and soil retention in low-income countries | [19] |

| Carbon Storage - Water Conservation | Mixed | Transition from trade-off to synergy observed in some regions | [22] |

| Habitat Quality - Soil Conservation | Significant synergy | Consistent positive relationship across multiple regions | [22] |

Spatial and Temporal Dynamics

The spatial heterogeneity of ES interactions presents both challenges and opportunities for land use optimization. Research in Suzhou City demonstrated that the relationship between water yield and carbon storage was predominantly trade-off at both 2km and 10km grid scales, while water yield and soil conservation showed mainly synergistic relationships [20]. However, the spatial agglomeration characteristics differed significantly across scales, highlighting the importance of multi-scale analysis.

Temporally, ES relationships can undergo significant transitions. In Henan Province, carbon storage-water conservation and habitat quality-water conservation relationships changed from trade-off to synergistic over the study period [22]. These temporal dynamics underscore the non-static nature of ES interactions and the need for regular monitoring and adaptive management. Furthermore, research has revealed that the ratio of trade-offs to synergies corresponds to national income levels, with higher-income countries typically exhibiting stronger synergies among ESs [19].

Implementation Framework for Land Use Optimization

The ultimate goal of analyzing ES trade-offs and synergies is to inform spatially explicit land use optimization. This requires translating analytical findings into practical spatial planning decisions. The following framework integrates the protocols and tools described previously into a comprehensive implementation workflow:

1. Ecological Security Pattern Identification

- Integrate ES assessments with landscape connectivity analysis

- Apply Morphological Spatial Pattern Analysis (MSPA) and Minimum Cumulative Resistance (MCR) models to identify ecological sources and corridors [23]

- Establish hierarchical ESPs (core, buffer, transition zones) as spatial constraints for development

2. Zoning Based on ES Bundles

- Use self-organizing maps (SOM) or k-means clustering to identify regions with similar ES bundles [23]

- Define management zones based on dominant ES interactions:

- Comprehensive Service Function Zones: High multiple ES provision with strong synergies

- Ecological Buffer Zones: Moderate ES provision with mixed interactions

- Agricultural Development Priority Zones: Trade-offs between provisioning and regulating services

- Urban Development Zones: Typically low ES provision with specific trade-off patterns

3. Scenario Evaluation and Selection

- Implement Protocol 3 to simulate land use patterns under alternative development scenarios

- Quantify ES outcomes for each scenario using the methods from Protocol 1

- Evaluate scenario performance against multiple objectives (ecological, economic, social)

- Select optimal scenario based on stakeholder preferences and sustainability criteria

4. Adaptive Management Integration

- Establish monitoring systems to track changes in ES relationships over time

- Implement feedback mechanisms to adjust management strategies as relationships evolve

- Develop ecological compensation mechanisms to address unavoidable trade-offs

- Create participatory governance structures that incorporate local knowledge

This implementation framework provides a structured approach for integrating ES trade-off and synergy analysis into land use planning processes, enabling more sustainable and resilient landscape management.

Application Notes: Core Concepts and Quantitative Synthesis

Conceptual Foundation

Ecosystem service bundles are defined as sets of ecosystem services that repeatedly appear together in time and space through synergetic relationships [24]. Identifying these bundles and their spatiotemporal evolution is essential for enhancing regional ecosystem services, managing functional areas, and informing ecological and environmental protection policies [24]. Ecosystem service hotspots are areas delivering high levels of multiple ecosystem services, while coldspots supply significantly lower levels [25]. Research demonstrates that these bundles exhibit clear spatial differentiation, with identical bundles showing substantial spatial clustering [24].

Quantitative Synthesis of Spatiotemporal Dynamics

The following tables synthesize key quantitative findings from recent research on ecosystem service bundles and hotspots.

Table 1. Documented Changes in Ecosystem Service Supply and Distribution

| Metric | Documented Change | Spatial Context & Study Period | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall ES Supply | Significant decline | Beressa watershed (1972-2047) | [25] |

| Hotspot Area | Decreased over time; comprised ~24% of space on average | Beressa watershed | [25] |

| Coldspot Area | Increased over time; comprised ~48% of space on average | Beressa watershed | [25] |

| Water Yield (WY) | Average annual growth rate of 4.71%; spatial increase area >90% | Luo River Basin (1999-2020) | [26] |

| Soil Conservation (SC) | Average annual growth rate of 8.97%; spatial increase area >90% | Luo River Basin (1999-2020) | [26] |

| Carbon Storage (CS) | Average annual growth rate of 0.05%; spatial increase area >90% | Luo River Basin (1999-2020) | [26] |

| Habitat Quality (HQ) | Average annual decrease of 0.31%; 39.76% of region declined | Luo River Basin (1999-2020) | [26] |

Table 2. Characteristic Ecosystem Service Bundles Identified in Regional Studies

| Bundle Name/Acronym | Characteristic Ecosystem Services | Primary Location & Landscape Features | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grain Production Bundle (GPB) | High food production (FP) | Anhui Province; generally lower in north, higher in south for FP | [24] |

| Mountain Ecological Conservation Bundle (MECB) | High habitat quality (HQ), carbon sequestration (CS), soil conservation (SC) | Anhui Province; Western Dabie Mountains, southern mountains | [24] |

| Urban Living Bundle (ULB) | High associated with construction land expansion | Anhui Province; progressively increased in area (2000-2020) | [24] |

| Core Protection Bundle (CPB) | Not specified | Anhui Province; remained largely stable in number (2000-2020) | [24] |

| Bundle 1 & 2 | High hydrological regulating services (water yield, sediment retention) and habitat maintenance | Beressa watershed; western areas with gentle slopes, high grassland proportion | [25] |

| Bundle 3 | High agricultural provisioning (crop yield) | Beressa watershed; various distribution | [25] |

| Bundle 4 | Increased climate regulation | Beressa watershed; eastern areas with high elevation, steep slopes, high plantation proportion | [25] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessment of Ecosystem Service Dynamics and Bundle Identification

Primary Objective: To quantify the spatiotemporal dynamics of vital ecosystem services (ESs), identify statistically significant hotspots/coldspots, and delineate ecosystem service bundles in a watershed or regional study area.

Study Design and Data Preparation

- Design: This is a geospatial-temporal analysis, typically retrospective and observational, conducted over a defined historical period (e.g., 1999-2020) [26] [24].

- Spatial Units: Analysis can be performed at various scales, including watersheds [25] [26], provinces [24], or at finer administrative levels like townships [24] or using a grid-based approach [9].

- Data Requirements: The following datasets are required, with all raster data harmonized to a uniform resolution and coordinate system [24]:

- Land Use/Land Cover (LULC) Data: For multiple time points, derived from satellite imagery or land survey data [26] [9] [24].

- Meteorological Data: Including precipitation and temperature [26] [24].

- Topographic Data: Digital Elevation Model (DEM) to derive slope [26] [24].

- Soil Data: Soil type and texture [26] [24].

- Vegetation Data: Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) [26] [24].

- Socio-economic Data: (Optional) Population density, economic indicators [24].

The workflow for this protocol is systematic and iterative, progressing from data preparation through to final zoning recommendations.

Ecosystem Service Quantification

- Modeling: Utilize established models to quantify key ecosystem services. The InVEST (Integrated Valuation of Ecosystem Services and Tradeoffs) model is widely applied for this purpose [25]. Commonly assessed services include:

- Water Yield: Using the InVEST Annual Water Yield model [25] [26].

- Sediment Retention/Soil Conservation: Using the InVEST Sediment Retention model [25] [26] [24].

- Habitat Quality/Maintenance: Using the InVEST Habitat Quality model [25] [26] [24].

- Carbon Storage/Sequestration: Using the InVEST Carbon Storage and Sequestration model [26] [24].

- Crop Yield/Food Production: Estimated based on LULC and agricultural statistics [25] [24].

- Trend Analysis: Apply Sen's slope estimator and the Mann-Kendall test to analyze long-term trends of each ES over the study period [26].

Statistical Analysis and Bundle Identification

- Spatial Autocorrelation: Perform Hotspot and Coldspot analysis (e.g., using Getis-Ord Gi* statistic) to identify statistically significant (p < 0.05) spatial clusters of high (hotspots) and low (coldspots) values for ESs [25] [26].

- Bundle Identification: Use clustering algorithms to identify ES bundles. The k-means clustering algorithm is commonly used for its distinct clustering structure [24]. Alternatively, Self-Organizing Maps (SOM), an unsupervised artificial neural network, can be used for high fault tolerance and stability [26]. The optimal number of clusters (k) is determined based on criteria such as the elbow method.

Protocol 2: Driving Force Analysis and Land Use Optimization

Primary Objective: To determine the dominant natural and socio-economic drivers of ES bundle evolution and to simulate optimized land use scenarios for enhancing ecosystem service provision.

Driving Force Analysis

- Driver Selection: Select potential driving factors based on literature and local context. These typically include:

- Geographical Detector Model: Use the Geographical Detector (GeoDetector), particularly the Optimal Parameter-based Geographical Detector (OPGD), to quantify the explanatory power (q-statistic) of each factor on the spatial heterogeneity of ESs and bundles. The OPGD optimizes spatial scale and discretization of continuous data to avoid subjectivity [26] [24].

- Spatial Regression: Apply Multi-scale Geographically Weighted Regression (MGWR) to analyze the spatial heterogeneity of the impact of driving factors on ES trends. MGWR accounts for scale differences in various explanatory variables, providing more accurate results than non-spatial models [26].

Land Use Optimization Simulation

- Scenario Definition: Develop multiple future scenarios, such as:

- Demand Projection: Use a System Dynamic (SD) model or Gray Multi-objective Optimization (GMOP) to project future land demands under each scenario, considering socio-economic drivers like population and GDP growth [27] [9].

- Spatial Allocation: Couple land demand projections with a spatial simulation model. The Patch-generating Land Use Simulation (PLUS) model is recommended as it uses a random forest algorithm to mine land change drivers and simulates patch-level changes with high accuracy [9]. Critical spatial constraints must be incorporated, including Permanent Basic Cropland (PBC), Boundaries for Urban Development (BUD), and Red Lines for protecting Ecosystems (RLE), as mandated by national spatial planning [9].

- ESV Assessment and Validation: Estimate the Ecosystem Service Value (ESV) for optimized land use patterns using a modified equivalent factor method [9]. Compare the outcomes of different scenarios to inform decision-making.

The relationship between driving factors and the resulting land use and ecosystem service patterns is complex and forms a feedback loop, which can be visualized as follows.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3. Essential Models, Software, and Data for ES Bundle and Hotspot Research

| Tool Name | Type/Category | Primary Function in Research | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| InVEST Suite | Software Model | Quantifying and mapping multiple ecosystem services (water yield, carbon, habitat, sediment) | [25] [26] |

| k-means Clustering | Algorithm | Identifying ecosystem service bundles by grouping spatial units with similar ES compositions | [24] |

| Self-Organizing Map (SOM) | Algorithm (Unsupervised Neural Network) | Identifying ES bundles with high fault tolerance and stability | [26] |

| Geographical Detector (GeoDetector) | Spatial Statistical Model | Quantifying the driving forces behind ES spatial heterogeneity and detecting factor interactions | [26] [24] |

| Multi-scale Geographically Weighted Regression (MGWR) | Spatial Regression Model | Analyzing the spatial heterogeneity and scale of driving factors' impacts on ES | [26] |

| Patch-generating Land Use Simulation (PLUS) | Software Model | Simulating future land use changes at the patch level under different scenarios | [9] |

| Sen's Slope & Mann-Kendall Test | Statistical Method | Analyzing long-term trends and significance of changes in ES time series | [26] |

| Getis-Ord Gi* | Spatial Statistical Method | Delineating statistically significant hotspots and coldspots of ecosystem services | [25] [26] |

| Gray Multi-objective Optimization (GMOP) | Model | Optimizing future land use quantities based on multiple objectives and constraints | [9] |

Advanced Computational Frameworks for Spatial Optimization

Deep Learning Surrogates for High-Fidelity Ecosystem Service Modeling

Ecosystem services (ES) are the critical benefits that natural systems provide to human society, encompassing provisioning, regulating, supporting, and cultural services [8] [28]. Spatially explicit assessment of these services is fundamental to land use optimization, enabling researchers and policymakers to quantify ecological impacts of anthropogenic activities and environmental changes. Traditional process-based models for ES assessment, while mechanistically detailed, often present substantial computational constraints that limit spatial resolution, temporal scope, and scenario exploration capabilities [29].

Deep learning (DL) surrogate models present a transformative approach to high-fidelity ecosystem service modeling by leveraging data-driven approximations of complex ecological processes. These surrogates learn the input-output relationships of conventional models from existing simulation data, achieving radical computational acceleration while maintaining predictive accuracy [29]. This protocol details the implementation of deep learning surrogates within spatially explicit land use optimization research, providing application notes and experimental procedures for researchers developing these methodologies.

Key Applications and Quantitative Performance

Deep learning surrogates have demonstrated advanced capabilities across multiple ecosystem service domains. The table below summarizes documented performance metrics from recent implementations.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Deep Learning Surrogates in Ecosystem Service Modeling

| Application Domain | Deep Learning Architecture | Reported Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cultural Ecosystem Service Classification | ResNet-152 (CNN) | 91% accuracy in image classification | [30] |

| Biophysical Driver Modeling | XGBoost | 85% accuracy in predicting CES drivers | [30] |

| Coastal Flood Inundation Prediction | Deep Learning Surrogate | High-fidelity spatiotemporal predictions | [29] |

| Firewood Use Prediction (South Africa) | Multiple ML Algorithms | 64-91% accuracy | [31] |

| Natural & Cultural ES Supply-Demand | Transformer-Shapley/BiLSTM | Captured nonlinear dynamics and thresholds | [32] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Developing DL Surrogates for Hydrodynamic Inundation Modeling

This protocol outlines the procedure for creating a deep learning surrogate to emulate computationally intensive coastal flooding models, based on methodologies successfully applied in Tianjin, China [29].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Computational Tools

| Item | Specification/Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Training Data Source | Outputs from process-based models (e.g., Delft3D, SWAN) | Provides labeled data for surrogate training |

| Geospatial Data | Digital Elevation Models (DEMs), land use maps, infrastructure data | Input features for spatial predictions |

| Deep Learning Framework | TensorFlow, PyTorch, or Keras | Model architecture implementation and training |

| High-Performance Computing | GPU clusters (e.g., NVIDIA Tesla series) | Accelerates model training and hyperparameter tuning |

| Spatial Analysis Library | GDAL, ArcPy, Whitebox Tools | Preprocessing of geospatial input data |

Methodological Steps

Training Data Generation: Execute the high-fidelity hydrodynamic model (e.g., Delft3D) across a diverse set of input conditions, including varying sea-level rise scenarios, storm intensities, tidal conditions, and precipitation patterns. The number of simulations should be statistically sufficient to capture the model's behavior.

Input-Output Feature Engineering: Extract relevant input features from the hydrodynamic model setup, including bathymetry, topography, boundary conditions, and wind fields. The corresponding output features are spatiotemporal inundation maps (depth and extent).

Spatial Data Preprocessing: Standardize all geospatial data to a consistent coordinate system and spatial resolution. Normalize input features to a common scale (e.g., 0-1) to stabilize neural network training.

Surrogate Model Architecture Design: Implement a convolutional neural network (CNN) or U-Net architecture capable of processing spatial input grids and generating corresponding spatial output predictions. Incorporate residual connections to facilitate training of deep networks.

Model Training and Validation: Partition the dataset into training (70%), validation (15%), and testing (15%) subsets. Use the validation set for hyperparameter optimization and early stopping. Quantify performance on the held-out test set using metrics like Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), and critical success index for inundation extent.

Uncertainty Quantification: Implement Monte Carlo dropout or deep ensembles during inference to generate probabilistic predictions and quantify epistemic uncertainty in the surrogate model outputs.

The workflow for this protocol is summarized in the diagram below:

Protocol 2: Cultural Ecosystem Service Mapping via Image Recognition

This protocol details the procedure for assessing cultural ecosystem services (CES) using deep learning-based image classification, adapting the framework that achieved 91% accuracy in river landscape studies [30].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for CES Image Recognition

| Item | Specification/Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Image Repository | Geotagged photos from platforms like Flickr, Instagram | Raw data reflecting cultural values and recreational use |

| Pretrained CNN Models | ResNet-152, VGG-16, Inception-v3 | Transfer learning for image classification |

| Annotation Platform | Labelbox, CVAT, or custom tools | Manual labeling for training data creation |

| Spatial Analysis Tool | ArcGIS, QGIS with Python scripting | Linking image classifications to spatial contexts |

| XGBoost Library | Python XGBoost package | Modeling relationships between CES and biophysical drivers |

Methodological Steps

Image Data Collection: Download large datasets (e.g., >5,000 images) of geotagged photographs from social media platforms using API access. Filter by relevant geographic boundaries and time periods.

CES Category System Definition: Establish a hierarchical classification scheme for cultural ecosystem services (e.g., aesthetic enjoyment, recreation, spiritual value, social interaction) based on established typologies like the Common International Classification of Ecosystem Services (CICES).

Training Data Annotation: Manually label a substantial subset of images (e.g., 2,000-5,000) according to the CES categories. Implement quality control through multiple annotators and consensus mechanisms.

CNN Model Fine-Tuning: Adapt a pre-trained convolutional neural network (e.g., ResNet-152) by replacing the final classification layer with project-specific categories. Fine-tune the model weights using the annotated image dataset.

Spatial Hotspot Identification: Aggregate classification results to spatial units (e.g., watersheds, grid cells) to identify areas with high CES provision. Apply kernel density estimation to create continuous CES provision maps.

Biophysical Driver Analysis: Train interpretable machine learning models (e.g., XGBoost) to identify relationships between classified CES hotspots and environmental variables (e.g., land cover, topography, accessibility). Perform residual analysis to reveal areas with added cultural value not explained by demographic factors alone.

The workflow for this protocol is summarized in the diagram below:

Protocol 3: Multi-Scenario Land Use Optimization with Integrated AI

This protocol combines deep learning surrogate modeling with land use simulation for spatially explicit ecosystem service optimization, building upon approaches used in the Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau and Inner Mongolia [8] [28].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials for Land Use Optimization

| Item | Specification/Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| PLUS Model | Patch-generating Land Use Simulation model | Projects land use changes under various scenarios |

| InVEST Model | Integrated Valuation of Ecosystem Services | Quantifies multiple ecosystem services |

| Bayesian Belief Network | Probabilistic graphical model | Handles uncertainty in ES relationships |

| Gradient Boosting Machines | XGBoost, LightGBM, CatBoost | Identifies key drivers of ecosystem services |

| Spatial Priority Optimization | Custom scripts in R or Python | Delineates areas for conservation/restoration |

Methodological Steps

Historical Land Use Change Analysis: Quantify land use transitions over multiple time periods (e.g., 2000, 2010, 2020) using satellite imagery classification. Calculate transition matrices and spatial pattern metrics.

Ecosystem Service Baseline Assessment: Use the InVEST model to quantify key ecosystem services (e.g., carbon storage, habitat quality, water yield, soil retention) for historical reference years. Validate model outputs with field measurements where available.

Driver Analysis with Machine Learning: Train gradient boosting models to identify the relative importance of environmental (e.g., climate, topography) and anthropogenic (e.g., population density, infrastructure) drivers on ecosystem service provision.

Scenario Definition: Develop distinct future scenarios (e.g., natural development, ecological priority, planning-oriented) based on different policy objectives and climate projections.

Land Use Projection: Utilize the PLUS model to simulate future land use patterns for each scenario, incorporating the identified drivers and transition probabilities.

ES Trade-off Analysis: Evaluate the ecosystem service outcomes for each scenario using either the full InVEST models or pre-trained DL surrogates. Apply Bayesian Belief Networks to model the complex, nonlinear relationships and trade-offs between different services.

Spatial Priority Optimization: Identify priority areas for conservation, restoration, or specific land management interventions using multi-criteria decision analysis and optimization algorithms that maximize ecosystem service bundles.

The workflow for this protocol is summarized in the diagram below:

Validation and Integration Framework

Rigorous validation is essential for establishing the credibility of deep learning surrogates in ecosystem service modeling. The validation framework must address both technical performance and ecological relevance.

Table 5: Surrogate Model Validation Framework

| Validation Dimension | Metrics and Methods | Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Predictive Accuracy | Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), R² | MAE < 5-10% of observed range; R² > 0.8 |

| Spatial Pattern Retention | Spatial autocorrelation analysis, pattern metrics | Similar spatial structure to original models |

| Uncertainty Characterization | Confidence intervals, prediction variance | Quantified uncertainty bounds for all predictions |

| Ecological Process Representation | Response curve analysis, sensitivity analysis | Preservation of known ecological relationships |

| Decision-making Robustness | Scenario comparison, priority area congruence | Consistent conservation priorities with original models |

The integration of these surrogate models into land use optimization requires careful consideration of scale dependencies and cross-sectoral influences [13]. Researchers should explicitly document model fidelity—the degree to which a model accurately represents the real-world ecological system for its intended purpose [33]—and avoid overstating claims beyond validation evidence. Current research indicates machine learning applications in ecosystem services often lack robust validation, with 59% of studies not testing model generalizability and 67% not performing hyperparameter tuning [34].

Deep learning surrogates represent a paradigm shift in high-fidelity ecosystem service modeling, enabling previously computationally prohibitive analyses for spatially explicit land use optimization. When implemented following these protocols and validation standards, these approaches can dramatically accelerate scenario analysis, enhance spatial resolution, and uncover complex nonlinear relationships in human-environment systems. The integration of data-driven surrogates with process-based understanding creates powerful hybrid approaches for addressing pressing sustainability challenges in an era of rapid environmental change.

Multi-Objective Evolutionary Algorithms for Pareto-Optimal Solutions

In the realm of spatially explicit land use optimization, researchers and planners face the fundamental challenge of balancing multiple, often conflicting, ecosystem service demands. Objectives such as maximizing agricultural yield, enhancing carbon sequestration, maintaining water yield, and conserving biodiversity cannot be simultaneously optimized to their individual extremes. Multi-Objective Evolutionary Algorithms (MOEAs) provide a powerful computational framework for addressing these complex trade-offs by generating a set of Pareto-optimal solutions, where improvement in one objective necessitates deterioration in another [35] [36].

These algorithms have become indispensable tools in ecological informatics and land use science, enabling the exploration of complex solution spaces in high-dimensional optimization problems. By employing population-based search strategies inspired by natural evolution, MOEAs can efficiently navigate the combinatorial complexity of land allocation problems, which are characterized by vast decision spaces and multiple constraints [37] [36]. This document provides application notes and experimental protocols for implementing MOEAs in spatially explicit land use optimization research, with a specific focus on managing trade-offs among ecosystem services.