Overcoming High-Resolution Accelerometer Data Storage Constraints in Biomedical Research

This article addresses the critical challenge of managing high-volume, high-resolution accelerometer data in biomedical and drug development research.

Overcoming High-Resolution Accelerometer Data Storage Constraints in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article addresses the critical challenge of managing high-volume, high-resolution accelerometer data in biomedical and drug development research. It provides a comprehensive guide covering the fundamental scale of the data problem, modern storage and compression methodologies, practical optimization strategies for resource-constrained environments, and rigorous validation techniques to ensure data integrity. Aimed at researchers and scientists, the content synthesizes current technical solutions, including cloud computing, data reduction algorithms, and low-power sensor design, to enable scalable and reliable data handling for clinical trials and digital phenotyping.

Understanding the Data Deluge: The Scale of Accelerometer Storage Challenges in Research

The Proliferation of Accelerometers in Healthcare and Clinical Trials

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Resolving Data Quality and Signal Integrity Issues

Q1: My accelerometer data shows a constant zero reading or no signal variation. What should I check? A1: A flat-line signal typically indicates a power or connection failure.

- Procedure: First, use a voltmeter to check the Bias Output Voltage (BOV) at the data acquisition system. A properly functioning sensor with an 18-30 VDC supply should typically show a BOV of around 12 VDC [1].

- Diagnosis:

- If BOV is 0 VDC, check that power is turned on and connected. Then, inspect the entire cable length and junction box terminations for a short circuit [1].

- If BOV equals the full supply voltage (18-30 VDC), this indicates an open circuit. Check that the sensor is firmly connected at both ends and inspect the cable for damage. Cable and connector faults are more common than internal sensor failure [1].

Q2: The time waveform appears "jumpy" or has erratic spikes. What could be the cause? A2: Erratic waveforms are often caused by poor connections, ground loops, or signal overload.

- Procedure and Diagnosis:

- Inspect Connections: Check for corroded, dirty, or loose connectors. Clean and secure them, applying non-conducting silicone grease to reduce future contamination [1].

- Check for Ground Loops: A ground loop occurs if the cable shield is grounded at two points with differing electrical potential. Disconnect the shield at one end of the cable; if the problem disappears, you have confirmed a ground loop. The shield should be grounded at one end only [1].

- Check for Clipping: A clipped signal, where the waveform looks flattened at the top or bottom, indicates the amplifier is saturated. This can be confirmed by viewing the time waveform on an oscilloscope. Consider using a lower sensitivity sensor or a higher power supply voltage to mitigate this [1].

Q3: The FFT spectrum shows a dominant "ski-slope" pattern with high amplitudes at low frequencies. What does this mean? A3: A large ski-slope is a strong indicator of sensor overload or distortion, where the amplifier's limits have been exceeded [1]. This can be caused by:

- Mechanical Sources: Severe pump cavitation, steam release, or impacts from loose parts [1].

- Mounting Issues: A low mounted resonance frequency, often resulting from using a magnet or probe tip mount, can amplify high-frequency machine vibrations and lead to overload [1].

- Solution: Re-measure with the sensor mounted at a different location or with a more robust mounting method (e.g., adhesive stud) to see if the ski-slope disappears. This helps discriminate a mounting resonance from a genuine machine fault [1].

Q4: How can I prevent aliasing from corrupting my data? A4: Aliasing occurs when high-frequency signals masquerade as low-frequency signals due to an insufficient sampling rate [2].

- Procedure: To prevent aliasing, you must ensure that your signal contains no frequencies above half your sampling rate (the Nyquist frequency).

- Solution: The most practical method is to use an anti-aliasing filter, which is a low-pass filter that removes frequencies above the Nyquist frequency before the signal is sampled [2].

Guide 2: Addressing Data Storage and Transfer Challenges

Q1: I need to collect raw, high-resolution accelerometer data for a 7-day free-living study. What are my storage requirements? A1: Storage needs for raw accelerometer data are significant but manageable with modern hardware.

- Calculation: A device sampling tri-axial acceleration at 100 Hz for 7 days generates a substantial volume of data. While an exact figure isn't provided in the search results, one source notes that a "7-day collection" of raw acceleration data is about 0.5 Gigabytes [3]. Plan your storage infrastructure accordingly.

Q2: What strategies can I use to manage large volumes of accelerometer data from a multi-site clinical trial? A2: For large-scale studies, consider architectural and hardware solutions.

- Data Lakes: Develop unstructured data lakes designed to be AI-ready. These systems can handle the diverse data needed for analysis while incorporating robust security and compliance controls [4].

- Software-Defined Storage (SDS): Adopt SDS, which decouples data from hardware and offers unmatched flexibility in deploying, managing, and scaling storage resources across on-premises data centers and cloud environments [4].

- Cloud Storage with Caching: Use solutions like AWS S3 as a primary storage choice. Developers can overcome access penalties by using caching and other techniques, taking advantage of S3's resilience and availability for large-scale applications [4].

Q3: How can I ensure my data processing pipeline does not introduce significant latency? A3: Latency is determined by the time delay between sampling and the application software processing the information [2].

- Assessment: Define your latency requirement based on your application. A real-time biofeedback system requires very small latency, whereas a data-logging pedometer can tolerate much longer delays [2].

- Solution: Your latency requirement directly affects the buffer and pipeline design of your system. For multi-channel data, be aware that using a multiplexer to sample channels in sequence means they are not read simultaneously, which can add to perceived latency [2].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the difference between piezoelectric and MEMS accelerometers, and which is better for clinical research on human movement? A1: The choice depends on the specific measurements required.

- Piezoelectric: Made of quartz crystal; highly accurate with a large dynamic range and good linearity. They are ideal for measuring dynamic events like vibration and shock but cannot measure static acceleration (e.g., gravity for posture). Their lowest measurable frequency is between 0.1 and 1 Hz [2].

- MEMS (Micro Electro-Mechanical Sensors): Measure a change in capacitance; much lower cost and can measure static acceleration. This allows them to infer body segment orientation and posture. They are typically suitable for frequencies up to 100 Hz or 1 KHz [2] [5].

- Conclusion: For research requiring posture detection (sitting, standing) alongside movement, a MEMS accelerometer is necessary. For high-frequency vibration analysis, a piezoelectric sensor may be better [5].

Q2: What are the key considerations for choosing a body placement location for an accelerometer in a clinical trial? A2: The placement is a strong determinant of what information is captured [5].

- Hip/Lower Back: Tracks movement of the trunk and is often used as a standard for estimating overall physical activity energy expenditure [5].

- Wrist: Generally the most acceptable to participants during free-living monitoring, favoring protocol adherence, though the relationship between wrist movement and whole-body energy expenditure is more complex [3] [5].

- Thigh: Excellent for estimating posture (e.g., sitting vs. standing) from its orientation with respect to gravity [5].

- Note: No single placement is perfect. For example, wrist or trunk placement may underestimate activities like cycling [5].

Q3: What is "Bias Output Voltage (BOV)" and why is it important for troubleshooting? A3: The BOV is a DC bias voltage (typically ~12 VDC) upon which the dynamic AC vibration signal is superimposed. It is a key diagnostic tool [1].

- Importance: The BOV should be stable under normal operation. Trending this voltage can provide a record of sensor health. A sudden drop or change can indicate a developing fault, such as sensor damage from excessive temperature, shock, or electrostatic discharge [1].

Q4: We are planning a long-term study. How can we future-proof our data to allow for re-analysis with new algorithms? A4: The field of accelerometry is moving from proprietary "counts" to device-agnostic analysis of raw acceleration signals [3].

- Primary Strategy: Archive the raw acceleration signal data in standard SI units (m/s²) rather than only storing processed summary data (e.g., "counts" or activity scores). This preserves the maximum information and allows you to reprocess your data in the future as analytic methods evolve [3] [5].

Data Presentation Tables

Table 1: Accelerometer Types and Specifications for Clinical Research

| Feature | Piezoelectric Accelerometer | MEMS Accelerometer |

|---|---|---|

| Sensing Principle | Piezoelectric (quartz crystal) voltage [2] | Change in capacitance [2] |

| Static Acceleration | Cannot measure (transient only) [2] | Can measure (e.g., gravity, posture) [2] |

| Dynamic Range | Very large (several orders of magnitude) [2] | Smaller (one or two orders of magnitude) [2] |

| Frequency Range | 0.1/1 Hz to 10 KHz+ [2] | Up to 100 Hz / 1 KHz [2] |

| Linearity Error | Typically ≤2% [2] | Information Missing |

| Relative Cost | High [2] | Low (1/10 to 1/100 of piezo) [2] |

| Ideal Use Case | High-frequency vibration, shock analysis [2] | Postural assessment, low-frequency motion, cost-sensitive deployments [2] [5] |

Table 2: Data Storage and Management Considerations

| Parameter | Consideration & Impact on Research |

|---|---|

| Sampling Frequency | Higher frequencies (e.g., 100 Hz) allow a wider range of analyses and reproduction of waveforms but generate more data [5]. |

| Epoch Length | Shorter analysis epochs (e.g., 5s) optimize resolution; data can always be down-sampled later. Minute-by-minute epochs limit analytical flexibility [5]. |

| Data Format | Raw Signal (device-agnostic, future-proof, enables novel methods) [3]. Counts (proprietary, limited to existing models, useful for historical comparison) [3]. |

| Storage Requirement | Significant; example: ~0.5 GB for a 7-day collection of raw data [3]. |

| Monitoring Duration | Must be long enough to capture a stable average of habitual activity, considering day-to-day variation. Typically requires multiple days [5]. |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Accelerometer Data Processing Workflow for Clinical Research

Troubleshooting Sensor Bias Voltage

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table of Essential Materials and Software for Accelerometer Research

| Item | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Tri-axial MEMS Accelerometer | The primary sensor; measures acceleration in three dimensions, enabling capture of complex movements and, crucially, static acceleration for posture inference [2] [5]. |

| Standardized Adhesive Mounts | Ensures consistent and secure sensor attachment to the body (e.g., hip, thigh), minimizing motion artifact and preserving signal quality. |

| Data Logger with High-Capacity Storage | A portable device that stores the high-volume raw acceleration signal data collected over multiple days of free-living monitoring [3]. |

| Anti-Aliasing Filter | A critical signal processing component (hardware or software) that removes high-frequency noise above the Nyquist frequency to prevent aliasing artifacts in the sampled data [2]. |

| Bias Voltage (BOV) Trending Software | Diagnostic software (often part of monitoring systems) that tracks the sensor's DC bias voltage over time, providing an early warning for sensor faults or connection issues [1]. |

| Raw Data Processing Software (e.g., R, Python libraries) | Open-source tools that enable researchers to process raw acceleration signals, extract features, and apply machine learning models for activity type recognition and energy expenditure estimation [3]. |

| Open Table Format Data Lake (e.g., Apache Iceberg) | A modern data architecture that provides a low-cost, scalable, and reliable storage repository for raw and processed accelerometer data, facilitating re-analysis and ensuring data longevity [6]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the Nyquist-Shannon sampling theorem and why is it critical for my accelerometer study?

The Nyquist-Shannon sampling theorem states that to accurately capture a signal, the sampling frequency must be at least twice the highest frequency of the movement you intend to measure [7]. This prevents "aliasing," a distortion effect that misrepresents the true signal [7]. For example, a study on European pied flycatchers found that to classify a fast, short-burst behavior like swallowing food (with a mean frequency of 28 Hz), a sampling frequency higher than 100 Hz was necessary [7]. In contrast, for longer-duration, rhythmic movements like flight, a much lower sampling frequency of 12.5 Hz was sufficient [7].

Q2: How do I balance sampling frequency with device storage and battery life?

Higher sampling rates provide more detailed data but consume storage and battery faster [7]. To optimize this balance, you must align your sampling rate with your specific research objectives. The table below summarizes key considerations based on research aims.

Table: Sampling Frequency Guidelines for Different Research Objectives

| Research Objective | Recommended Sampling Frequency | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Classifying short-burst behaviours (e.g., swallowing, prey capture) | At least 1.4 times the Nyquist frequency of the behaviour [7] | Requires high frequency (>100 Hz in some cases) to capture rapid, transient movements [7]. |

| Estimating energy expenditure (ODBA/VeDBA) | Can be relatively low (e.g., 10-25 Hz) [7] | Lower frequencies are often adequate for amplitude-based metrics over longer windows [7]. |

| Classifying endurance, rhythmic behaviours (e.g., walking, flight) | Varies; can be as low as 12.5 Hz [7] | The required frequency depends on the specific movement's velocity [7]. |

Q3: My accelerometer outputs "counts" versus "raw data." What is the difference and which should I use?

Counts are proprietary, summarized data (e.g., activity counts per user-defined epoch) generated by the device's onboard processing. Data from different manufacturers are often not directly comparable [5] [3]. Raw data is the stored acceleration signal in SI units (m.s⁻²) before any processing [5]. The field is shifting toward using raw data because it allows for more sophisticated, device-agnostic analysis, improved activity classification, and the ability to re-analyze data as new methods emerge [5] [3].

Q4: What are the main data compression techniques available for managing large accelerometer datasets?

Table: Common Data Compression and Management Techniques

| Technique | Description | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| On-board Aggregation | Summarizing raw data into "counts" or features over an epoch (e.g., 1-minute periods) before storage [5]. | Reduces data volume but irreversibly loses raw signal information [5]. |

| Lossless Compression | Algorithms (e.g., Huffman coding) that reduce file size without losing any original data [8]. | Preserves all data but may offer less compression than lossy methods [8]. |

| Lossy Compression | Techniques that discard some data deemed less critical (e.g., certain frequencies) [9]. | Can greatly reduce data volume; requires careful selection to avoid losing scientifically important information [9]. |

| Model Compression | In AI applications, techniques like pruning and quantization reduce the size of models used to analyze the data [8]. | Enables efficient deployment of analysis models on devices with limited computational resources [8]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: My device storage fills up too quickly. Solution:

- Review Sampling Rate: Determine the minimum sampling frequency required for your key behaviors using the Nyquist theorem. Reducing an unnecessarily high frequency is the most effective way to save storage [7].

- Shorten Monitoring Duration: Weigh the benefits of continuous long-term monitoring against the data volume. Sometimes, shorter, more frequent sampling periods can effectively capture habitual activity [5].

- Explore Compression: If your device and research question allow, consider using lossless compression or storing pre-processed activity counts, acknowledging the trade-off in data richness [5] [8].

Problem: I am missing short but important behavioral events in my data. Solution:

- Increase Sampling Frequency: Short-burst behaviors require high sampling rates. One study found that sampling at 100 Hz was needed to detect rapid maneuvers like a flycatcher's prey capture [7].

- Analyze with Shorter Epochs: When calculating metrics like ODBA, using a shorter analysis window (e.g., 5-second epochs vs. 1-minute epochs) can improve the temporal resolution and help isolate brief events [5].

- Validate with Video: Synchronize a subset of your accelerometer data with video recordings. This allows you to visually identify the signal patterns of short-duration behaviors and verify your sampling rate is adequate [7].

Problem: I need to compare my data with older studies that used "counts." Solution:

- Collect Raw Data: If possible, configure new studies to collect and archive raw acceleration signals. This future-proofs your data, allowing you to derive counts using open-source algorithms while also enabling more advanced analyses [3].

- Harmonize Post-Processing: Explore collaborative efforts and open-source software that provide transparent methods for converting raw data into activity counts, which can improve cross-study comparability [3].

Experimental Protocol: Determining Minimum Sampling Frequency

Objective: To empirically determine the minimum required sampling frequency for classifying specific animal behaviors or human movements.

Materials:

- Tri-axial accelerometer capable of high-frequency raw data recording (e.g., ≥100 Hz).

- Synchronized high-speed video camera.

- Computer with signal processing software (e.g., MATLAB, R, Python).

Methodology:

- Data Collection: Record subjects performing the target behaviors using an accelerometer set to its highest frequency (e.g., 100 Hz). Simultaneously record high-speed video (e.g., 90 fps) as a ground truth reference [7].

- Data Annotation: Synchronize the video and accelerometer data timelines. Annotate the start and end times of each behavioral event of interest based on the video [7].

- Data Down-Sampling: From the original high-frequency dataset, create down-sampled versions (e.g., 50 Hz, 25 Hz, 12.5 Hz) using signal processing software.

- Model Training and Testing: Develop a machine learning model to classify behaviors using features extracted from the original, high-frequency dataset. Then, test this model's performance on the down-sampled datasets [7].

- Analysis: Compare the classification accuracy across the different sampling frequencies. The minimum acceptable sampling frequency is the lowest rate at which classification accuracy for your key behaviors does not significantly degrade.

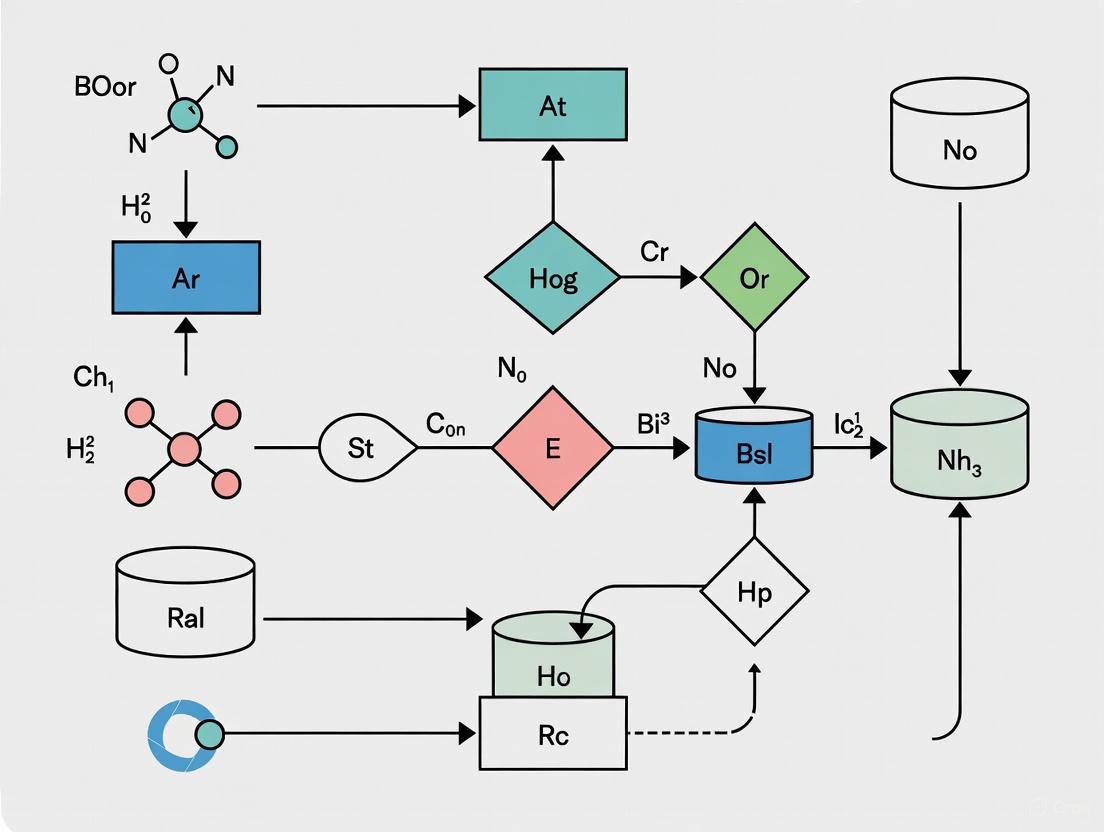

Workflow Diagram

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Tri-axial Raw Data Accelerometer | Measures acceleration in three perpendicular directions (vertical, anteroposterior, mediolateral), providing a comprehensive movement signature. Prefer devices that output raw data in SI units for maximum flexibility [5] [3]. |

| High-Speed Video Camera | Serves as ground truth for behavior annotation. Crucial for validating that accelerometer signals at various sampling rates accurately represent the observed behavior [7]. |

| Secure Data Storage System | For archiving large volumes of raw data. Systems should have robust backup procedures and may leverage cloud or high-capacity physical storage to manage terabyte-scale datasets [3]. |

| Signal Processing Software | Software platforms (e.g., R, Python with specialized libraries) are used to perform critical tasks like down-sampling data, filtering noise, extracting signal features, and building behavior classification models [5] [3]. |

| Leg-Loop Harness or Attachment | Provides a secure and consistent method for attaching the accelerometer to the subject, minimizing movement artifact and ensuring data quality. The placement site (e.g., back, wrist, thigh) strongly influences the signal [5] [7]. |

FAQs

1. How does the accelerometer's sampling rate and filter setting impact data quality and storage needs? The sampling rate (e.g., 90-100 Hz for human activity studies) and digital filter selection are fundamental data collection choices [10]. A higher sampling rate captures more signal detail but generates more data, directly increasing storage requirements and the power consumed for processing and transmission. The filter (e.g., Normal vs. Low-Frequency Extension) shapes the data by including or excluding certain frequency components, which can affect the accuracy of activity counts and subsequent analyses [10]. Choosing inappropriate settings can lead to "data format inconsistencies" or "ambiguous data," common issues that jeopardize data reliability [11].

2. What are the most effective strategies to extend battery life for long-term field data collection? The most effective strategies involve a combination of hardware selection and device configuration:

- Hardware: Select accelerometers designed for ultra-low power consumption, with current draw in the microamp (µA) range, which dynamically scale power with sampling rate [12].

- Configuration: Enable built-in power-saving modes, dim the screen if the device has one, and disable unnecessary wireless communications like Bluetooth and GPS when not in use [13] [14].

- Node Intelligence: Use devices with deep FIFO buffers and intelligent features that allow for local data processing. This minimizes the need for constant, power-intensive wireless transmission by sending only summarized or critical data [12].

3. How can we reduce the costs associated with transmitting high-volume accelerometer data? Minimizing transmission costs is best achieved by reducing the amount of data that needs to be sent. Key methods include:

- On-device Processing: Utilize the accelerometer's FIFO buffer and processing capabilities to perform initial data analysis or feature extraction on the node itself [12].

- Transmit Exceptions: Instead of streaming all raw data, configure the system to transmit only processed summaries, alerts, or data that exceeds specific thresholds (e.g., potential collision events) [15] [12].

- Leverage Wi-Fi: When available, use Wi-Fi for data synchronization, as it typically uses less power and may have lower associated costs than cellular networks [13].

4. What are the common data storage issues, and how can they be avoided in a research setting? Common data storage issues include [11] [16]:

- Data Loss: Due to hardware failure or human error.

- Inconsistent or Inaccurate Data: Caused by format mismatches, incorrect device calibration, or outdated data.

- Data Overload: Collection of massive volumes of irrelevant or redundant data.

- Orphaned Data: Data that is incompatible with existing systems or difficult to transform into a usable format. Prevention requires a robust data governance plan: implement regular and automated backup procedures (both on-site and off-site), define clear data validation and formatting rules at the point of collection, and establish policies for archiving and purging irrelevant data [11] [16].

5. Our research involves condition monitoring of machinery. Are MEMS accelerometers a suitable replacement for piezoelectric sensors? Yes, MEMS accelerometers are increasingly competing with piezoelectric sensors in condition-based monitoring (CBM) [12]. Key advantages of MEMS include their DC response (ability to measure very low frequencies, essential for monitoring slow-rotating machinery), ultra-low noise performance, higher levels of integration (with features like built-in overrange detection and FFT analysis), and significantly lower power consumption, which is critical for wireless sensor nodes [12]. While piezoelectric sensors traditionally offered wider bandwidths, specialized MEMS accelerometers now offer bandwidths sufficient for diagnosing a wide range of common machinery faults [12].

Troubleshooting Guides

Battery Life Issues

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Rapid battery drain during active sensing | Sampling rate or communication radio (BT/ Cellular) set too high. | Reduce the output data rate (ODR) to the minimum required for your signal of interest. Disable unused radios [13]. |

| Battery drains while the device is in storage or not in use | Background processes or "Always-On" features enabled. | Enable the device's ultra-low power wake-up or sleep mode (e.g., ~270 nA for some models) [12]. |

| Device will not hold a charge | Battery is damaged or has reached end of lifespan. | Check the device's battery health indicator. Replace the battery following manufacturer instructions [17]. |

| Inconsistent battery life across identical devices | Firmware or app version mismatch. | Ensure all devices and controlling applications are updated to the latest software version [17] [13]. |

Device Memory & Storage Problems

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| "Storage Full" error | Data accumulation exceeds device or local storage capacity. | Implement a data lifecycle management (DLM) strategy: automate data uploads to a central server/cloud and enable local deletion post-transmission [18] [16]. |

| Data corruption or inability to read files | Underlying hardware failure or improper device shutdown. | Regularly validate data integrity. Check storage hardware (e.g., SD card) for errors. Ensure proper shutdown procedures are followed [16]. |

| Data is stored but cannot be used by analysis tools | Data format inconsistencies or "orphaned data" [11]. | Establish and enforce a standard data format (e.g., for date/time) across all devices. Use a data quality management tool to profile datasets and flag formatting flaws [11]. |

| Data logs are missing or incomplete | FIFO buffer overflow or "data downtime" [11]. | Configure the device's FIFO buffer size appropriately for the sampling rate and transmission interval. Ensure reliable connectivity for automated data offloading [12]. |

High Transmission Costs & Failures

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High cellular data costs | Transmission of raw, high-frequency data. | Process data on the edge device and transmit only extracted features, summaries, or exceptions to minimize bandwidth use [12]. |

| Repeated transmission failures in the field | Poor cellular/Wi-Fi signal strength in deployment area. | Use a device that stores data locally during outages and resumes transmission when a stable connection is re-established. Consider deploying a local network gateway [16]. |

| "Data overload" consuming bandwidth and cloud storage [11] | Collecting and transmitting large volumes of irrelevant data. | Define data needs for the project and use filters on the device to eliminate irrelevant data from large collections before transmission [11]. |

Experimental Protocols & Data Management

Protocol 1: Determining Minimum Viable Sampling Rate

Objective: To establish the lowest sampling rate that retains necessary signal fidelity, thereby optimizing battery life and storage.

- Setup: Secure the accelerometer to a calibrated shaker table or a representative object (e.g., a motor housing).

- Data Collection: Record data at the device's maximum sampling rate (e.g., 400 Hz) while subjecting the unit to a range of known frequencies and amplitudes relevant to your study (e.g., 1-50 Hz for human gait, 1k-10k Hz for machinery).

- Down-sampling: In post-processing, digitally down-sample the high-rate data to progressively lower rates (e.g., 200 Hz, 100 Hz, 50 Hz).

- Analysis: For each down-sampled dataset, calculate key metrics (e.g., peak amplitude, FFT spectra) and compare them to the "gold standard" original data.

- Decision: Select the lowest sampling rate where the error in your key metrics remains below a pre-defined acceptable threshold (e.g., <5%).

Protocol 2: Power Consumption Profiling

Objective: To quantitatively measure and compare the power consumption of different device configurations.

- Setup: Connect the accelerometer to a programmable power supply and a high-precision digital multimeter in series to measure current draw.

- Baseline Measurement: Record the device's current consumption in its deepest sleep or power-down mode.

- Active Mode Testing: For each configuration (e.g., 100 Hz w/ BT off, 400 Hz w/ BT on), run the device while logging data. Measure the average and peak current.

- Battery Life Calculation: Use the formula: Battery Life (hours) = Battery Capacity (Ah) / Average Current Draw (A). Compare results across configurations to inform deployment choices.

Protocol 3: Implementing a Data Reduction Strategy

Objective: To reduce data volume at the source through on-device processing.

- Feature Selection: Identify computationally simple features that are meaningful for your research (e.g., min/max/mean, standard deviation, zero-crossing rate).

- FIFO Configuration: Program the accelerometer to collect data in a buffer (e.g., 512 samples).

- On-Device Logic: Implement an algorithm (if supported) that calculates the selected features from each buffer of raw data.

- Transmission: Transmit only the calculated feature vector instead of the entire raw data buffer, drastically reducing transmission payload size [12].

Data Presentation

Table 1: MEMS Accelerometer Selection Guide for Different Applications

| Application | Key Criteria | Recommended Specs | Power Consumption | Sample Devices/Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wearable Devices (VSM) | Ultra-low power, small size | Bandwidth: ~50-100 Hz, Range: ±2g - ±8g | 3 µA @ 400 Hz [12] | ADXL362, ADXL363 (with deep FIFO and temperature sensor) [12] |

| Condition Monitoring | Low noise, wide bandwidth | Bandwidth: >3 kHz, Range: ±50g - ±100g, High SNR | Varies with bandwidth | ADXL354/5, ADXL356/7 (low noise); ADXL100x family (wide bandwidth, overrange detection) [12] |

| IoT / Long-Term Deployment | Ultra-low power, integrated intelligence | Bandwidth: Application-specific | As low as 270 nA in wake-up mode [12] | Parts with integrated FFT, spectral alarms, and deep FIFO to minimize host processor workload [12] |

| Parameter | Impact on Battery Life | Impact on Storage/Memory | Impact on Transmission Cost | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High Sampling Rate | Major Negative Impact (linear increase) | Major Negative Impact (linear increase) | Major Negative Impact (linear increase) | Use the minimum rate required to capture your signal. |

| Raw Data vs. Processed Features | Minor Impact (processing is low power) | Major Positive Impact if processing reduces data | Major Positive Impact (dramatic reduction) | Process on-node and transmit features or exceptions. |

| Continuous vs. Interval Transmission | Major Impact (radio is power-hungry) | Major Impact (determines local storage needs) | Major Impact (continuous is costly) | Use deep FIFO buffers and transmit data in scheduled intervals. |

| High vs. Low G-Range | Negligible Impact | Minor Impact (on bit-depth) | Minor Impact | Select a range that fits the application to maintain resolution. |

Workflow Diagrams

Data Lifecycle Management Strategy

Sensor Configuration Decision Map

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Ultra-Low Power Accelerometers (e.g., ADXL362) | The core sensing element. Selected for its microamp-range current consumption and dynamic power scaling, which is fundamental for extending battery life in long-term studies [12]. |

| Deep FIFO Buffer | An integrated memory block within the sensor. Its function is to store batches of raw data, allowing the main system processor to remain in a low-power sleep state longer, significantly reducing overall system power consumption [12]. |

| Programmable Data Acquisition Gateways | Acts as a local hub. Its function is to aggregate data from multiple sensors via low-power protocols (e.g., BLE), perform initial data validation/filtering, and transmit condensed data to the cloud via Wi-Fi or cellular, optimizing transmission costs [16]. |

| Data Quality Management Tools | Software for profiling incoming datasets. Its function is to automatically flag quality concerns like duplicates, inconsistencies, or missing data early in the data lifecycle, preventing "data downtime" and ensuring reliable analytics [11]. |

| Predictive Maintenance Algorithms | On-device or edge intelligence. Its function is to analyze vibration trends (e.g., using FFT) to detect anomalies, enabling the transmission of alert flags instead of continuous raw data streams, thus conserving bandwidth and storage [12]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Storage & Data Collection Issues

| Problem | Probable Cause | Impact on Research | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Insufficient study duration | Device memory filled prematurely due to high sampling frequency or raw data collection. | Compromised assessment of habitual behaviors; insufficient data for reliable day-to-day variability analysis [5]. | Pre-calculate battery life and memory for settings; use a lower sampling frequency (e.g., 30-100 Hz) if raw data is not essential [10] [5]. |

| Low participant adherence | High participant burden from device size, wear location, or need for recharging. | Data loss and potential sampling bias, threatening internal validity [19]. | Choose a less obtrusive wear location (e.g., wrist); use devices with extended battery life; provide clear participant instructions [19]. |

| Incomparable data between studies | Use of proprietary "activity counts" with opaque, device-specific algorithms [20]. | Hinders data pooling, meta-analyses, and validation of findings across the research field [21] [20]. | Collect and store raw acceleration data (in gravity units) where possible; use open-source algorithms for processing [21] [5]. |

| Unexpected data loss or corruption | Manual data handling processes; lack of automatic backup systems. | Loss of valuable data, jeopardizing study results and insights [22]. | Utilize systems with automatic cloud upload and secure data backup features to preserve data integrity [22]. |

| Inability to monitor data collection in real-time | Traditional methods require physical device retrieval to check data quality. | Protocol deviations or device malfictions are discovered too late, leading to irrecoverable data gaps [22]. | Implement solutions with remote checking capabilities to verify data status and quality during the collection period [22]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. How do storage and battery limitations directly influence the methodological design of a study? Storage and battery capacity are primary factors in deciding key data collection protocols. To prevent memory from filling during a study, researchers must decide on:

- Sampling Frequency: Higher frequencies (e.g., 80-100 Hz) capture more raw signal detail but consume memory faster. Lower frequencies conserve memory but may miss high-frequency movements [10] [5].

- Epoch Length: Storing data in longer epochs (e.g., 60-second counts) was a traditional way to save memory, but it sacrifices the ability to analyze short, intermittent activity bursts. Modern best practice is to collect raw data with short epochs [10].

- Monitoring Duration: The chosen settings directly determine how many days of data can be recorded before a device must be collected or recharged. A minimum of 4 valid days, including a weekend day, is often required to estimate habitual activity [10] [5].

2. What are "activity counts" and why can their use be a constraint? Activity counts are summarized data, where raw acceleration signals are filtered and aggregated over a specific time interval (epoch) into a proprietary unit [21]. The main constraint is the lack of transparency and standardization; the algorithms generating these counts are often device-specific and have historically been proprietary [20]. This makes it difficult to compare results from studies using different brands of devices or even different generations of the same brand, effectively locking the research data into a specific device's ecosystem [21] [20].

3. What are the practical advantages of collecting raw accelerometry data? Collecting raw acceleration data in units of gravity (g) provides:

- Device Agnosticism: Raw data from different devices can be processed with the same, transparent open-source algorithms, enhancing comparability [5].

- Future-Proofing: As new and improved processing algorithms are developed, raw data can be re-analyzed to extract new information without needing to run a new study.

- Enhanced Analysis: Raw data enables more sophisticated analyses, including advanced activity type recognition and posture estimation [21] [5].

4. How can cloud technology and modern devices help overcome traditional storage constraints? Modern wearable accelerometers and cloud platforms directly address many historical limitations [22]:

- Automatic Data Upload: Data is seamlessly transferred to cloud storage, eliminating manual handling and risk of loss [22].

- Remote Device Management: Researchers can initialize, configure, and troubleshoot devices remotely, saving time and resources [22].

- Centralized Data Access: Cloud repositories allow research teams from different locations to access and analyze data collaboratively [22].

- Scalable Storage: Cloud storage can be expanded as needed, removing the physical memory constraints of the device itself.

Experimental Protocols for Mitigating Storage Constraints

The following workflow outlines a systematic approach to planning a data collection protocol that effectively manages storage and battery limitations.

Protocol Steps:

- Define Primary Research Objective: The choice of data type (raw vs. counts) and subsequent settings must be driven by the study's core scientific question [10] [5].

- Select Data Type:

- Raw Data: Choose this path for maximum analytical flexibility, future-proofing, and cross-study comparability. It is the recommended choice for new studies where the device capability exists [5].

- Activity Counts: This path may be necessary for comparison with historical data or when using older devices. Acknowledge the limitations in device-specificity and analytical flexibility [20].

- Determine Sampling Frequency:

- Calculate Resource Requirements:

- Estimate total memory required using the formula:

Memory (MB) = (Days of Recording × Hours per Day × 3600 × Sampling Frequency × Bytes per Sample × Number of Axes) / (1024 × 1024). - Confirm that the calculated need fits within the device's storage and expected battery life for the planned wear duration.

- Estimate total memory required using the formula:

- Feasibility Check and Iteration: If the requirements exceed device capacity, iterate by adjusting the sampling frequency, reducing the number of monitoring days, or selecting a device with greater resources. The goal is to find a balance that still validly answers the research question.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Tri-Axial Accelerometer | The core sensor that measures acceleration in three perpendicular dimensions (vertical, anteroposterior, mediolateral), providing a comprehensive picture of movement [5]. |

| Open-Source Processing Algorithms | Software tools (e.g., published Python packages) that allow for transparent, reproducible, and device-agnostic conversion of raw acceleration data into meaningful metrics like activity counts or movement intensity [20]. |

| Cloud Data Management Platform | A centralized system for remote device configuration, automatic data upload, secure backup, and collaborative data access, which streamlines operations and safeguards data integrity [22]. |

| Validated Wear Location Protocol | A standardized procedure for device placement (e.g., non-dominant wrist, hip) that ensures consistency within a study and improves the comparability of data across different studies [10] [19]. |

| Direct Calibration Methods | The use of controlled activities (e.g., treadmill walking) to establish study-specific intensity thresholds (cut-points) for classifying sedentary, light, moderate, and vigorous activity, which is more accurate than using published values [10]. |

Modern Architectures for Data Management: From Edge to Cloud

Leveraging Cloud Platforms for Scalable, Secure Data Storage and Analytics

Technical Support Center: FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

This support center is designed for researchers handling high-resolution accelerometer data. It provides solutions for common cloud storage and analytics challenges within the context of physical activity and health research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the primary benefits of using a cloud platform for high-volume accelerometer data?

Cloud analytics platforms are vital for handling today's growing data volumes and analytics needs. For accelerometer research, this translates to several key benefits [23] [24]:

- Scalability: Platforms scale storage and processing power elastically based on your data volume, which is essential when dealing with raw, high-frequency accelerometer signals that can generate gigabytes of data per participant per week [3] [23].

- Cost Efficiency: A pay-as-you-go subscription model eliminates large upfront investments in physical servers and allows you to pay only for the storage and computing you use [23].

- Advanced Analytics & AI: Many platforms offer built-in machine learning and AI-powered analytics, which are crucial for developing sophisticated models to classify activity types and estimate energy expenditure from raw acceleration signals [3] [23] [25].

- Centralized & Integrated Data: These platforms seamlessly integrate real-time data from multiple sources, providing a single source of truth—for example, combining accelerometer data with other physiological or clinical datasets [23].

2. How durable and available is my research data in the cloud?

Cloud storage is designed for extremely high durability and availability.

- Durability: Services like Google Cloud Storage are designed for 99.999999999% (11 nines) annual durability, meaning the risk of data loss is exceptionally low [26].

- Availability: To maximize data availability for your research team, you should store data in a multi-region or dual-region bucket location. For the highest level of protection against data loss, consider Turbo replication for dual-region buckets, which is designed to replicate new objects to a separate region within a target of 15 minutes [26].

3. What is the best way to share individual data objects with collaborators?

The easiest and most secure method is to use a signed URL [26]. This provides time-limited access to anyone in possession of the URL, allowing them to download the specific object without needing a cloud platform account. Alternatively, you can use fine-grained Identity and Access Management (IAM) conditions to grant selective access to objects within a bucket [26].

4. How can I protect my research data from accidental deletion or ransomware?

Cloud services offer several mechanisms to protect your data [27] [26]:

- Encryption: Encrypt all data at rest on your devices and in the cloud. For data in transit, always use SSL/TLS protocols [28]. For sensitive datasets, you can manage your own encryption keys using a service like Azure Key Vault [28].

- Backups: Frequently back up your data to a secure external hard drive or a properly vetted cloud service. If using an external drive, store it safely and avoid leaving it connected to prevent ransomware from accessing it [27].

- Versioning & Retention Policies: Use cloud storage features that control data lifecycles. You can implement retention policies that prevent objects from being deleted until a set period has passed [26].

5. We need to process data in real-time from our accelerometers. Is this possible?

Yes. Many cloud data platforms support real-time streaming and operational analytics [24]. This capability allows for immediate processing of data streams, which can be used for real-time activity monitoring or immediate feedback in intervention studies. These platforms can ingest and analyze continuous data flows, enabling operational dashboards that monitor performance metrics with automated responses [24].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Slow Data Transfer Speeds to Cloud Storage

Problem: Uploading large accelerometer data files is taking too long, slowing down research progress.

Diagnosis and Solution:

- Check Your Internet Connection: Ensure you have a stable, high-bandwidth connection. For very large datasets (e.g., multiple terabytes), consider using a dedicated high-speed WAN link like Azure ExpressRoute [28].

- Use Accelerated Endpoints: Cloud Storage uses a global DNS network to transfer data to the closest Point of Presence (POP), which can significantly boost performance over the public internet. This is typically enabled by default and included at no extra charge [26].

- Optimize File Sizes and Use Compression: While raw data is valuable, compressing older datasets or batch-processing smaller files into larger, optimized formats (like Parquet) can reduce transfer times.

- Leverage Client Libraries: Use official cloud client libraries, which are often optimized for performance. The following code snippet for Python shows how to enable debug logging to help diagnose transfer issues.

Issue 2: CORS Errors When Accessing Data from a Web Application

Problem: Your web-based analysis tool cannot fetch accelerometer data from cloud storage due to CORS (Cross-Origin Resource Sharing) errors.

Diagnosis and Solution:

This error occurs when a web application tries to access resources from a cloud bucket that is on a different domain, and the bucket is not configured to allow this.

- Review Bucket CORS Configuration: Verify that your bucket has a CORS configuration set up and that the origin of your web application (e.g.,

http://localhost:8080orhttps://my-lab-domain.com) matches anOriginvalue in the configuration exactly (including scheme, host, and port) [29]. - Check the Correct Endpoint: Ensure your application is not making requests to the

storage.cloud.google.comendpoint, which does not allow CORS requests. Use the appropriate JSON or XML API endpoint [29]. - Inspect the Network Request: Use your browser's developer tools to check the request and response headers. In Chrome:

- Open Developer Tools (> More Tools > Developer Tools).

- Go to the Network tab.

- Reproduce the error.

- Click on the failing request and check the Headers tab for details [29].

- Clear the Preflight Cache: Browsers cache preflight responses. Lower the

MaxAgeSecvalue in your CORS configuration, wait for the old cache to expire, and try the request again. Remember to set it back to a higher value later [29].

Issue 3: High Cloud Computing Costs for Data Processing

Problem: The cost of running data processing and analytics jobs on the cloud is exceeding the project's budget.

Diagnosis and Solution:

- Audit and Right-Size Resources: Regularly review your computing resources (e.g., virtual machines, database clusters) and ensure they are not over-provisioned for the workload.

- Use Scalable, Serverless Options: Platforms like Google BigQuery offer a serverless model where you pay only for the queries you run, not for provisioned capacity. This can lead to significant savings for intermittent processing tasks [24].

- Implement Data Lifecycle Policies: Automate the transition of infrequently accessed raw data to * colder, cheaper storage classes * (e.g., from Standard to Archive/Nearline storage) after a certain period [26].

- Monitor and Set Budget Alerts: Use the cloud platform's cost management tools to set up budgets and alerts to notify you when spending exceeds a predefined threshold.

Experimental Protocol: From Raw Signal to Research Insight

This protocol details the methodology for storing and analyzing high-resolution raw accelerometer data on a cloud platform, moving beyond outdated count-based approaches [3].

1. Data Acquisition & Ingestion

- Device Settings: Configure triaxial accelerometers (e.g., ActiGraph, GENEActiv, Axivity) to capture and store the raw acceleration signal in gravitational units (g), not proprietary "counts." A sampling frequency of 30-100 Hz is common [3] [25].

- Data Transfer: Securely upload

.csvor binary data files from the device to a centralized, encrypted cloud storage bucket (e.g., Amazon S3, Google Cloud Storage, Azure Blob Storage). Use tools like the Google Cloud CLI (gcloud storage) or SDKs for automation [26].

2. Cloud-Based Preprocessing & Feature Extraction

- Data Validation: Run automated checks for missing data or device malfunctions.

- Signal Processing: Isolate the human movement component (AC) from gravity (DC) using high-pass and low-pass filters [5]. The static (DC) component can be used to infer body posture [3].

- Feature Extraction: Extract features in both time and frequency domains from the raw signal. This can be done using serverless functions (e.g., AWS Lambda, Google Cloud Functions) or processing engines like Apache Spark on Databricks [3] [25] [24].

Table: Common Features Extracted from Raw Accelerometer Signals [25]

| Domain | Category | Example Metrics |

|---|---|---|

| Time | Uniaxial | Mean, Variance, Standard Deviation, Percentiles (e.g., 25th, 50th, 75th), Range (Max-Min) |

| Time | Between Axes | Correlation between axes, Covariance between axes |

| Frequency | Spectral | Dominant Frequency, Peak Power, Spectral Energy, Entropy |

3. Analytical Modeling Leverage the cloud's computing power for advanced modeling:

- Machine Learning for Activity Classification: Use platforms like Azure Machine Learning or Google Vertex AI to train and deploy models (e.g., CNNs, LSTMs) that classify specific activity types (sitting, walking, running) from the extracted features [3] [25] [30]. A BiLSTM model optimized with Bayesian optimization has achieved classification accuracy of 97.5% [30].

- Association and Prediction: Use scalable statistical environments (e.g., R or Python on cloud VMs) to run regression-type models that associate PA metrics with health outcomes or to predict future health events [25].

The workflow below visualizes this end-to-end experimental protocol.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Cloud & Data Solutions

Table: Essential resources for managing accelerometer data in the cloud.

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Snowflake | Cloud Data Platform | Separates storage and compute for scalable analytics on diverse accelerometer datasets [24]. |

| Google BigQuery | Serverless Data Warehouse | Enables high-speed SQL queries on large datasets; integrates with ML tools for activity prediction models [24]. |

| Databricks | Data & AI Platform | Provides a "lakehouse" architecture combining data lake flexibility with data warehouse performance, ideal for collaborative data science [24]. |

| Axivity AX3 | Waveform Accelerometer | A research-grade device capable of storing tri-axial raw acceleration at 100 Hz for extended periods [25] [5]. |

| ActiLife / GGIR | Data Processing Software | Open-source and commercial software used to process raw accelerometer data into analyzable metrics [25]. |

| Azure Key Vault | Key Management | Manages and controls cryptographic keys used to encrypt research data at rest in the cloud [28]. |

Compression Techniques at a Glance

The following table summarizes the core data compression strategies relevant to handling high-resolution accelerometer data in healthcare IoT systems.

| Compression Type | Key Principle | Best-Suited Data Types | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lossless [31] [32] | Preserves all original data; allows for perfect reconstruction. | Medical images, textual data, annotated sensor data [31] [33]. | No loss of critical information; essential for clinical diagnosis [32]. | Lower compression ratios (CR) compared to lossy methods [34]. |

| Lossy [34] | Discards less critical data to achieve higher compression. | Continuous sensor streams (e.g., accelerometer), video, audio [35] [34]. | Significantly smaller file sizes; reduces storage/bandwidth needs [34]. | Irreversible data loss; potential for compression artifacts [33] [34]. |

| TinyML-based (e.g., TAC) [35] | Evolving, data-driven compression using machine learning on the device. | Real-time IoT sensor data streams (e.g., vibration, acceleration) [35]. | High compression rates (e.g., 98.33%); adapts to data changes; low power consumption [35]. | Higher computational complexity during development; relatively novel approach [35]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: For my research on human movement via accelerometers, should I use lossless or lossy compression to minimize storage without compromising data integrity?

The choice depends on the specific analysis you intend to perform. If your research requires precise, sample-level analysis of vibration signatures or subtle tremor patterns, a lossless method is safer to guarantee no diagnostic features are altered [32]. However, for analyzing broader movement patterns, activity classification, or long-term trend analysis, a well-designed lossy compression strategy can be appropriate. It can achieve much higher compression ratios, making it feasible to store and transmit data from long-duration studies [35] [34]. We recommend testing your analytics pipeline on a subset of data compressed with a lossy algorithm to validate that key features for your analysis are preserved.

Q2: My IoT healthcare device is triggering "transmission timeout" errors when sending compressed accelerometer data. What could be wrong?

This typically points to an issue in the communication chain. Please check the following:

- Inconsistent Payload Size: Verify that your compression algorithm's output is stable. Anomalies or spikes in the data can sometimes cause the compression algorithm to output a much larger packet, exceeding the expected frame size and causing timeouts [35].

- Network Bandwidth Fluctuations: The compressed data packet, while smaller than raw data, might still be too large for the available network bandwidth at a given moment. This is common in LPWANs like LoRaWAN [35]. Implement a packet chunking mechanism to break large compressed datasets into smaller, transmittable units.

- Processor Overload: Confirm that the compression task itself is not consuming too many CPU cycles, leaving insufficient resources for the communication stack to function timely. Profiling the device's resource usage is recommended [35].

Q3: After compressing and decompressing my high-resolution accelerometer data, my machine learning model's performance dropped significantly. How can I troubleshoot this?

This indicates that the compression process is removing information that your model deems important.

- Identify Critical Features: First, analyze which features (e.g., specific frequency components, peak amplitudes, cross-axis correlations) are most important for your model's predictions.

- Benchmark with Lossless: Compress a dataset using a lossless method. If your model's performance is maintained, the issue is with the aggressiveness of your lossy compression.

- Adjust Lossy Parameters: If using a lossy technique, increase its fidelity (e.g., use a lower quantization step, a higher bitrate, or a less aggressive threshold in an evolving algorithm like TAC) [35]. The goal is to find a balance where file size is reduced, but the features important to your model are retained.

- Re-train the Model: Consider re-training your machine learning model on data that has gone through the compression-decompression cycle. This can make the model robust to the specific artifacts introduced by your chosen compression algorithm.

Experimental Protocols for Compression Analysis

This section provides a detailed methodology for evaluating compression techniques in a research setting, tailored for high-resolution accelerometer data.

Protocol 1: Benchmarking Compression Performance

Objective: To quantitatively compare the performance of different compression algorithms on a standardized accelerometer dataset.

Materials:

- Dataset: A labeled dataset of high-resolution 3-axis accelerometer data, encompassing various activities (walking, running, resting) and potential artifacts.

- Algorithms: Selected algorithms for testing (e.g., ZIP/GZIP for lossless; DCT-based for lossy; a custom TAC implementation) [35] [32] [34].

- Computing Environment: A standardized computing environment (e.g., Python with SciPy, MATLAB) to ensure consistent timing measurements.

Methodology:

- Data Preparation: Segment the raw accelerometer data into fixed-length epochs (e.g., 1-minute windows).

- Baseline Calculation: For each data epoch, calculate the original file size (

Size_original). - Compression Execution: For each algorithm and epoch, execute the compression and record:

- The compressed file size (

Size_compressed). - The time taken to compress the data (

Time_compress). - The time taken to decompress the data (

Time_decompress).

- The compressed file size (

- Calculation of Metrics:

- Compression Ratio (CR):

CR = Size_compressed / Size_original - Space Saving:

Space Saving (%) = (1 - CR) * 100 - Throughput:

Throughput (MB/s) = Size_original / Time_compress

- Compression Ratio (CR):

- Analysis: Compare the algorithms by plotting CR vs. Throughput and Space Saving vs. Throughput to identify trade-offs.

Protocol 2: Evaluating Signal Fidelity Post-Compression

Objective: To assess the impact of lossy compression on the signal quality and the preservation of clinically or scientifically relevant features.

Materials:

- Test Signal: A clean, high-fidelity accelerometer recording with known characteristics (e.g., specific dominant frequencies from a simulated tremor).

- Feature Set: A predefined set of features to be extracted (e.g., signal energy, dominant frequency, zero-crossing rate, cross-correlation between axes).

Methodology:

- Reference Feature Extraction: Extract the predefined features from the original, uncompressed test signal.

- Compress-Decompress Cycle: Process the test signal through the lossy compression and subsequent decompression.

- Test Feature Extraction: Extract the same set of features from the reconstructed signal.

- Fidelity Calculation: Calculate fidelity metrics by comparing the reference and test features.

- Percent Root-mean-square Difference (PRD):

PRD = sqrt( sum( (Original - Reconstructed)² ) / sum(Original²) ) * 100 - Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR): A higher PSNR indicates better quality [35].

- Feature-specific Error: Calculate the absolute or relative error for each individual feature (e.g., error in dominant frequency in Hz).

- Percent Root-mean-square Difference (PRD):

- Analysis: Determine if the fidelity loss and feature errors are within acceptable limits for the intended research application.

Experimental Workflow for Data Compression

The diagram below outlines a systematic workflow for evaluating data compression techniques for accelerometer data in a research project.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key computational tools and algorithms that serve as essential "reagents" for experiments in data compression for IoT-enabled healthcare.

| Tool/Algorithm | Function | Typical Application in Healthcare IoT Research |

|---|---|---|

| Tiny Anomaly Compressor (TAC) [35] | An evolving, eccentricity-based algorithm for online data compression. | Compressing real-time streams from body-worn accelerometers and other physiological sensors; ideal for low-power microcontrollers. |

| Discrete Cosine Transform (DCT) [35] [34] | A transform-based technique that concentrates signal energy into fewer coefficients. | A benchmark lossy method for compressing periodic signal data (e.g., repetitive movement patterns from accelerometers). |

| Soft Compression [32] | A lossless method that uses data mining to find and leverage basic image components. | Compressing multi-component medical images (e.g., MRI, CT) by exploiting structural similarity; can be adapted for 2D representations of sensor data. |

| JPEG2000 (with Wavelets) [31] [33] | A wavelet-based compression standard supporting both lossless and lossy modes. | Used in medical imaging; can be researched for compressing spectrograms or time-frequency representations of sensor signals. |

| Arithmetic Coding [31] [32] | An entropy encoding algorithm that creates a variable-length code. | A core component in many lossless compression pipelines (e.g., after transformation or prediction steps) to further reduce file size. |

| EBCOT (Embedded Block Coding with Optimal Truncation) [31] | A block-based coding algorithm that generates an embedded, scalable bitstream. | Used in image compression; its principles are useful for developing scalable compression for high-dimensional sensor data arrays. |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between standard PCA and Functional PCA (FPCA), and when should I choose one over the other?

Standard PCA is designed for multivariate data where each observation is a vector of features. In contrast, Functional PCA (FPCA) treats each observation as a function or a continuous curve, making it suitable for analyzing time series, signals, or any data with an underlying functional form [36]. FPCA decomposes these random functions into orthonormal eigenfunctions, providing a compact representation of functional variation [37]. You should consider FPCA when your data is inherently functional, such as high-resolution accelerometer readings, where preserving the smooth, time-dependent structure is crucial for analysis [38] [36]. Standard PCA would treat each time point as an independent feature, potentially missing important temporal patterns.

Q2: My high-dimensional dataset is so large that standard PCA runs into memory errors. What scalable solutions exist?

For extremely tall and wide data (where both the number of rows and columns are very large), standard distributed PCA implementations in libraries like Mahout or MLlib can fail with out-of-memory errors, especially when dimensions reach millions [39]. A modern solution is the TallnWide algorithm, which uses a block-division approach. This method divides the computation into manageable blocks, allowing it to handle dimensions as high as 50 million on commodity hardware, whereas conventional methods often fail at around 10 million dimensions [39]. The key is that this block-division strategy mitigates memory overflow by breaking down interdependent matrix operations.

Q3: How do I determine the optimal number of principal components to retain for my accelerometer data?

A common strategy is to use a scree plot and look for an "elbow point" where the explained variance levels off. A practical guideline is to retain enough components to explain 80-90% of the cumulative variance in your data [40]. For accelerometer data, which is often high-dimensional, this helps balance the trade-off between data compression and information retention. Retaining too few components loses important signal, while too many components can lead to overfitting and increased computational load [38] [40].

Q4: My data is non-linear. Is PCA still an appropriate method, and what are the alternatives?

Standard PCA is a linear technique and may perform poorly on data with complex non-linear relationships [40]. If you suspect strong non-linearities in your data, you should consider non-linear dimensionality reduction techniques. Kernel PCA can handle certain types of non-linear data by performing PCA in a higher-dimensional feature space [40]. Other powerful alternatives include t-SNE or autoencoders, which are designed to discover more intricate, non-linear patterns in data [40].

Q5: What are the most critical data pre-processing steps before applying PCA?

Proper data pre-processing is essential for meaningful PCA results. The most critical steps are:

- Centering and Scaling: Always standardize your variables to have a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one. Features on larger scales will otherwise dominate the principal components, regardless of their actual importance [40].

- Handling Missing Data: PCA cannot be applied directly to data with missing values. You must use appropriate imputation techniques to fill in missing entries [41] [40].

- Outlier Detection and Removal: Outliers can severely distort the principal components. Detect and handle outliers before applying PCA, as they can skew the results, particularly in smaller datasets [40].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Memory Overflow with High-Dimensional Data

Problem: Your computation fails due to insufficient memory when running PCA on a dataset with a very large number of features (e.g., D > 10M).

Solution: Implement a scalable PCA algorithm designed for tall and wide data.

- Recommended Algorithm: Use the TallnWide algorithm [39].

- How it works: It employs a block-division strategy based on a variant of Probabilistic PCA (PPCA). The data's parameter matrix is divided into

Iblocks (I = 4is a good starting point), and the Expectation-Maximization (EM) algorithm is applied to these manageable blocks instead of the entire matrix at once [39]. - Implementation Tip: If you are using a distributed computing framework like Spark, you can tune the number of blocks dynamically based on your cluster's resources to optimize performance [39].

Issue 2: Poor Model Generalization on New Data

Problem: Your PCA-reduced model performs well on your initial dataset but fails to generalize to new data, such as accelerometer data from a different farm or subject.

Solution: This is often a sign of overfitting, which is common with high-dimensional data. Revise your validation strategy.

- Use Rigorous Cross-Validation: Avoid simple random splits. Implement a farm-fold cross-validation (fCV) or leave-one-subject-out cross-validation. This means iteratively training on data from all but one farm (or subject) and testing on the held-out one. This provides a more realistic estimate of how your model will perform in real-world, unseen conditions [38] [42].

- Combine with Dimensionality Reduction: A study on accelerometer data for dairy cattle showed that applying ML models to data reduced via PCA or FPCA, combined with farm-fold cross-validation, significantly improved the robustness and generalizability of the models compared to using raw data [38].

Issue 3: Ineffective Dimensionality Reduction with Functional Data

Problem: Standard PCA applied to time-series data (e.g., accelerometer traces) produces noisy, uninterpretable principal components that do not capture smooth temporal patterns.

Solution: Switch to Functional PCA (FPCA), which incorporates smoothness into the components.

- Methodology: FPCA can be implemented using a sparse thresholding algorithm for high-dimensional functional data [37]:

- Projection: Mean-center the observed functional data and project it onto a chosen basis (e.g., B-splines or Fourier basis) up to a truncation level

s_n. - Thresholding: Retain only the basis coefficients whose variance exceeds a noise-adaptive threshold. This step

I^ = {(j,l): σ_jl² ≥ (σ²/m)(1+α_n)}drastically reduces the dimensionality by filtering out noise-dominated coefficients [37]. - Eigen-Decomposition: Perform the eigen-decomposition on the reduced covariance matrix from the retained coefficients to obtain the dominant eigenfunctions.

- Projection: Mean-center the observed functional data and project it onto a chosen basis (e.g., B-splines or Fourier basis) up to a truncation level

- Handling Gaps: For functional data with large gaps (common in satellite or sensor data), a space-time fPCA method that combines a weighted rank-one approximation with roughness penalties can effectively reconstruct missing entries and identify main variability patterns [41].

Protocol 1: Implementing Scalable PCA with the TallnWide Algorithm

This protocol is designed for datasets where the number of dimensions (columns) D is prohibitively large [39].

- Data Partitioning: Split the

N × Ddata matrix intoSgeographically distributed partitions (e.g., by data center). - Parameter Blocking: For each partition, further divide the parameter (subspace) matrix into

Icolumn blocks. The number of blocksIcan be tuned dynamically. - Distributed E-step: For each data partition

sand parameter blocki, compute the partial posterior expectation. This step is embarrassingly parallel. - Geo-Accumulation: Transmit only these partial results (not raw data) to a central, geographically ideal datacenter to minimize communication costs.

- M-step: At the central node, aggregate all partial results to update the global principal components

V. - Iterate: Repeat steps 3-5 until the EM algorithm converges.

Protocol 2: Applying FPCA to High-Resolution Accelerometer Data

This protocol is based on a study that successfully used FPCA to analyze accelerometer data from dairy cattle for foot lesion detection [38].

- Data Collection: Fit 3-axis accelerometers (e.g., AX3 Logging accelerometer) to subjects to collect high-resolution movement data.

- Data Structuring: Treat the collected data from each subject and session as a multivariate functional observation.

- Dimensionality Reduction: Apply FPCA to the raw accelerometer data. This reduces the thousands of time-point features into a small set of functional principal component (fPC) scores.

- Model Training: Use the fPC scores as features in a machine learning classifier (e.g., logistic regression, random forest).

- Validation: Validate the model using a strict farm-fold cross-validation (fCV) approach to ensure generalizability.

Performance Comparison of Dimensionality Reduction Methods

The table below summarizes findings from a study comparing methods on accelerometer data from 383 dairy cows [38] [42].

| Method | Description | Key Performance Insight |

|---|---|---|

| Raw Data + ML | Applying ML models directly to high-dimensional accelerometer data. | High risk of overfitting; reduced utility due to the "wide" data structure (many features, few samples). |

| PCA + ML | Applying ML to a lower-dimensional representation from standard PCA. | Improved performance over raw data by retaining key information and reducing overfitting. |

| FPCA + ML | Applying ML to scores from Functional PCA. | Effectively captures the time-series nature of the data; provides a robust and interpretable feature set for classification tasks. |

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential tools and software for implementing PCA/FPCA in high-dimensional data research.

| Item Name | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Spark with TallnWide Algorithm | A distributed computing framework and algorithm for handling PCA on extremely tall and wide datasets (dimensions >10M) [39]. |

| AX3 Logging 3-axis Accelerometer | A device for collecting high-fidelity, three-dimensional movement data over extended periods, ideal for generating functional data [38]. |

| R/fdaPDE Library | A software library for performing Functional Data Analysis, including FPCA for spatio-temporal data with complex domains and missing data [41]. |

| Scree Plot / Elbow Method | A simple graphical tool to determine the optimal number of principal components to retain by visualizing explained variance [40]. |

| Farm-Fold Cross-Validation (fCV) | A validation strategy that provides realistic performance estimates for models applied to new, independent locations or groups [38]. |

Workflow and Signaling Diagrams

PCA vs. FPCA Decision Workflow

This diagram outlines the logical process for choosing between standard PCA and Functional PCA for a given dataset.

Functional PCA (FPCA) Implementation Process

This diagram visualizes the key steps in the sparse FPCA algorithm for high-dimensional functional data [37].

Welcome to the Technical Support Center

This resource provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with practical guidance for implementing intelligent edge processing to overcome data storage constraints in research involving high-resolution accelerometers.

FAQs: Core Concepts

1. What is intelligent edge processing in the context of sensor data? Intelligent edge computing is a distributed model where computation and data storage are placed closer to the sources of data, such as accelerometers, rather than in a centralized data center [43]. For sensor data, this means running algorithms on the device itself or on a local gateway to analyze and reduce data before it is transmitted or stored [44].

2. Why is reducing accelerometer data volume at the edge critical for research? High-resolution accelerometers can generate vast amounts of data. Sending all this raw data to the cloud places immense demand on network bandwidth and storage infrastructure [43] [45]. Edge processing mitigates this by performing data reduction locally, which lowers bandwidth demand, reduces operational costs, and enables faster, real-time insights [45] [46].

3. What are the common architectural models for edge processing? There are three prevalent models [44]:

- Streaming Data: Sends all raw data to the cloud (least efficient for storage constraints).

- Edge Preprocessing: Uses intelligent algorithms at the edge to decide what data is important and should be transmitted.

- Autonomous Systems: Processes data entirely at the edge to make rapid decisions, logging only outcomes or summaries.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Edge AI Model Produces Unpredictable or Inaccurate Results After Deployment

| Potential Cause | Solution / Verification Step |

|---|---|

| Infrastructure Drift | Ensure a consistent, version-controlled software and hardware environment across all edge deployments to prevent performance drift [47]. |

| Insufficient Data for Model Training | Validate models against real-world edge data scenarios, including situations with less data, missing data, or low-quality data [48]. |

| Lack of OT/IT Collaboration | Foster collaboration between data scientists (IT) and domain experts (Operational Technology). Integrate heuristic knowledge from researchers to refine algorithms [48]. |

Issue 2: High Bandwidth Usage Despite Edge Processing Implementation

| Potential Cause | Solution / Verification Step |

|---|---|

| Ineffective Data Filtering | Review and optimize the machine learning model or algorithm responsible for data reduction at the edge to ensure it correctly identifies and discards non-essential data [44]. |

| Transmitting Raw Data | Verify the system configuration to ensure that the edge node is set to transmit only processed data or alerts, not continuous raw accelerometer streams [45]. |

| Lack of Compression | Implement lossless or lossless compression encoding on the processed data before transmission [49]. |

Issue 3: Edge Processor Instance Shows "Warning" or "Error" Status

| Potential Cause | Solution / Verification Step |

|---|---|

| High Resource Usage | Check CPU and memory thresholds. Scale out the edge system by adding more instances or reinstall on a host machine with more resources [50]. |

| Expired Security Tokens/Certificates | Verify and synchronize the system clock on the host machine via NTP. Update expired CA certificates for the operating system [50]. |

| Lost Connection | If an instance status is "Disconnected," check the host machine and network connectivity. Review supervisor logs on the instance itself for root causes [50]. |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Implementing Lossless Compression for Accelerometer Signals