Optimizing GPU Kernel Execution: Advanced Configurations for Accelerated Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive guide to optimizing GPU kernel execution configurations, specifically tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development.

Optimizing GPU Kernel Execution: Advanced Configurations for Accelerated Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to optimizing GPU kernel execution configurations, specifically tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development. It covers foundational CUDA concepts, modern methodological approaches including AI-driven optimization, practical troubleshooting with profiling tools, and validation techniques to measure performance gains. By applying these strategies, scientists can significantly accelerate computationally intensive tasks like virtual screening and molecular docking, thereby streamlining the drug discovery pipeline.

GPU Architecture and Kernel Fundamentals for Computational Scientists

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: What is the functional relationship between a CUDA Core, a Streaming Multiprocessor (SM), and thread execution?

A CUDA Core is a basic arithmetic logic unit (ALU) within an SM that performs integer and floating-point calculations [1]. It is not an independent processor that executes threads on its own.

The Streaming Multiprocessor (SM) is the fundamental, self-contained processing unit of an NVIDIA GPU [1]. It is responsible for executing all threads. Threads are grouped into warps of 32 threads, which is the fundamental unit of execution for an SM [2] [3]. The SM's warp schedulers manage these warps, and it takes multiple clock cycles for the SM's resources to issue a single instruction for all 32 threads in a warp [4] [3]. Therefore, CUDA Cores are the execution units that carry out the arithmetic operations for individual threads within the warps that the SM is processing.

FAQ 2: Should I maximize the number of blocks or the number of threads per block for efficiency?

You should aim for a balanced configuration that maximizes occupancy, which is the ratio of active warps on an SM to the maximum possible active warps [3]. Neither extremely small nor extremely large blocks are optimal.

- Larger thread blocks (e.g., 256 or 512 threads) can more efficiently use shared memory and synchronize within a block.

- Sufficient block count is necessary to keep all SMs on the GPU busy, as multiple thread blocks can execute concurrently on one multiprocessor [3].

The key is to ensure there are enough active warps to hide latency caused by memory operations or instruction dependencies [2] [3]. The CUDA Occupancy Calculator can help determine the optimal block size and count for your specific kernel.

FAQ 3: My GPU is not being fully utilized during kernel execution. What could be wrong?

Low GPU utilization often stems from poor workload distribution or latency issues. Here are common causes and solutions:

- Insufficient Parallelism: The total number of threads (threads per block × number of blocks) is too small to occupy all SMs. Use a large number of blocks (significantly more than the number of SMs) and a multiple of 32 threads per block.

- Low Occupancy: Kernel resource usage (like registers or shared memory) is too high, limiting the number of concurrent warps per SM. Try to reduce resource usage to allow more warps to be active simultaneously, which helps hide latency [3].

- Memory Latency: Threads are frequently stalled waiting for data from global memory. Structure your code to promote coalesced memory accesses and use faster memory spaces like shared memory when possible [5].

FAQ 4: What is the critical difference between CPU cores and GPU Streaming Multiprocessors?

The key difference lies in their design philosophy: CPU cores are designed for low-latency on a few threads, while GPU SMs are designed for high-throughput on thousands of threads [2].

Feature CPU Cores GPU Streaming Multiprocessors Goal Minimize execution time for a single thread Maximize total work done across thousands of threads Cores Fewer, more complex cores Many, simpler processor cores (CUDA Cores) Thread Management Hardware-managed caches & speculative execution [2] Hardware-scheduled warps for ultra-fast context switching (< 1 clock cycle) [2] Parallel Threads Dozens [2] Thousands of truly parallel threads [2] GPUs achieve high throughput by using a massive number of threads to hide the latency of operations like memory accesses [2].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Suboptimal Kernel Performance and Low Throughput

This guide provides a methodology to diagnose and resolve common performance bottlenecks in CUDA kernel execution, framed within kernel execution configuration research.

Experimental Protocol for Performance Analysis

Baseline Measurement:

- Use

nvprofor the NVIDIA Nsight Systems profiler to collect initial performance data. - Key metrics: Kernel execution time, SM occupancy, achieved DRAM bandwidth, and warp execution efficiency.

- Use

Analyze Workload Distribution:

- Objective: Ensure the workload is evenly distributed across all SMs.

- Method: Check profiler metrics for "Streaming Multiprocessor Activity". Idle SMs indicate an insufficient number of thread blocks. The grid should contain more blocks than the GPU has SMs.

Optimize Thread Block Configuration:

- Objective: Find the optimal balance between block size and count to maximize occupancy.

- Method: Use the CUDA Occupancy Calculator API. Systematically vary the threads per block (in multiples of 32, from 128 to 1024) while keeping the total work constant. The table below shows a sample analysis framework.

Table: Exemplar Data for Occupancy vs. Block Size Analysis (Theoretical A100 GPU)

Threads per Block Blocks per SM Theoretical Occupancy Observed Memory Bandwidth (GB/s) Kernel Duration (ms) 128 16 100% 1350 1.5 256 12 94% 1480 1.2 512 6 75% 1420 1.3 1024 3 56% 1300 1.6 Profile Memory Access Patterns:

- Objective: Identify and fix non-coalesced global memory accesses, a major performance bottleneck.

- Method: In the profiler, check metrics for "Global Memory Load/Store Efficiency". Efficiency below 80% suggests uncoalesced access. Restructure data or use shared memory for efficient data rearrangement [6].

Iterate and Validate:

- Implement changes based on the above steps and re-run the profiling. Use an analytical roofline model to compare achieved performance against the hardware's theoretical peak [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Key Software Tools for GPU Kernel Optimization Research

| Tool / Library | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| CUDA Toolkit (nvcc, nvprof) | Core compiler and profiler for building and baseline analysis of CUDA applications [7]. |

| NVIDIA Nsight Systems | System-wide performance profiler that provides a correlated view of CPU and GPU activity to identify large-scale bottlenecks. |

| NVIDIA Nsight Compute | Detailed kernel profiler for advanced, instruction-level performance analysis and micro-optimizations. |

| CUDA Occupancy Calculator | Spreadsheet or API to theoretically model the relationship between kernel resource usage and SM occupancy [3]. |

| Kernel Tuning Toolkit (KTT) | Automated framework for performing autotuning over a defined search space of kernel parameters [6]. |

| CUTLASS | CUDA C++ template library for implementing high-performance matrix-multiplication (GEMM) and related operations [6]. |

Issue: Kernel Fails to Launch or Exhibits Incorrect GPU Selection

Diagnosis and Resolution Protocol

Verify GPU Detection:

Check Device Ordering for Multi-GPU Systems:

- Problem: The default device order in

nvidia-smimay not match the PCI bus ID order, causing kernels to launch on an unintended GPU [9]. - Solution: Set the environment variable

CUDA_DEVICE_ORDER=PCI_BUS_IDbefore launching your process. This ensuresCUDA_VISIBLE_DEVICESindexing is consistent with the PCI bus order [9].

- Problem: The default device order in

Validate PCIe Link Width:

- Command: Check that the current link width is at the expected maximum (e.g., x16) using

lspci -vvd <device_id> | grep -i lnksta:[8]. - Symptom: A reduced link width (e.g., x8 or x4) can severely limit data transfer bandwidth to the GPU.

- Command: Check that the current link width is at the expected maximum (e.g., x16) using

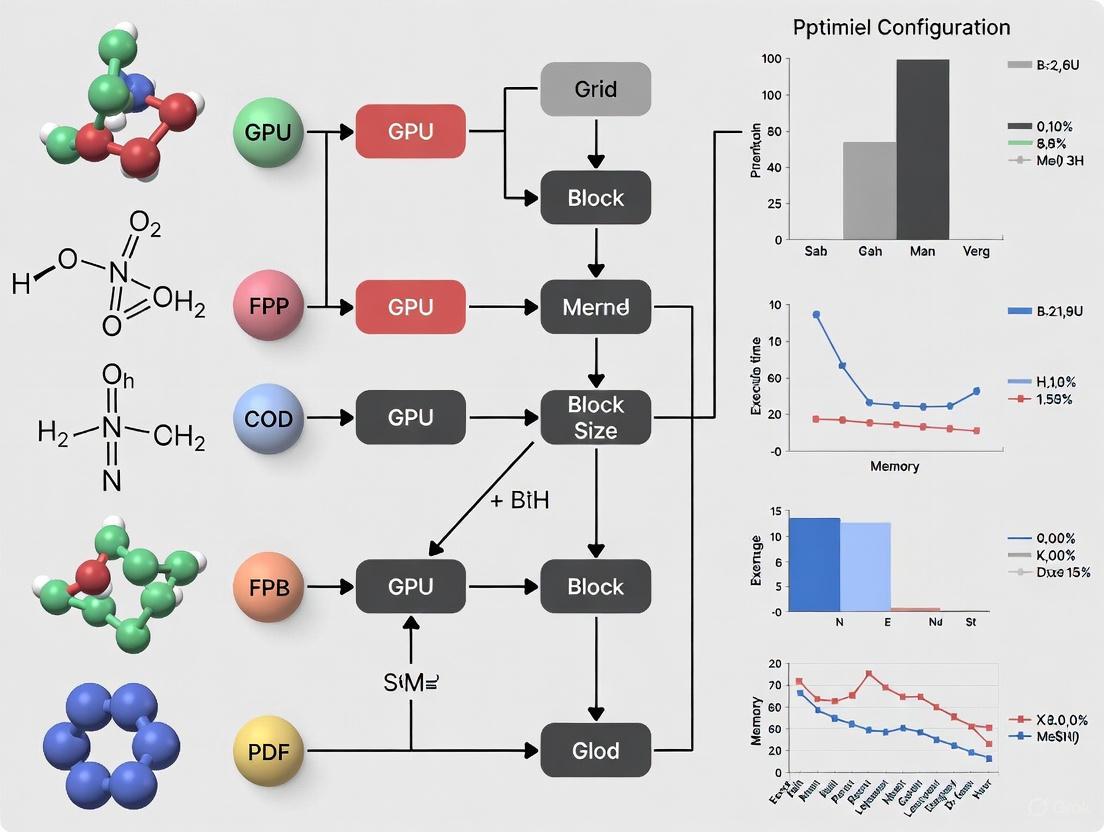

Conceptual Diagrams

FAQs: Understanding Core Performance Concepts

This section addresses frequently asked questions about the key metrics that determine the efficiency of GPU kernel execution, providing a foundation for performance analysis and optimization.

Q1: What is occupancy, and why is it important for kernel performance?

Occupancy is the ratio of active warps on a Streaming Multiprocessor (SM) to the maximum number of active warps the SM can support [10]. It is a measure of how effectively the GPU's parallel processing capabilities are utilized.

- Importance: High occupancy helps hide memory latency. When some warps are stalled waiting for data from memory, the warp scheduler can switch to other active warps that are ready to execute, thereby keeping the computational units busy [11]. However, it is a common misconception that 100% occupancy is always the goal; sometimes, trading off some occupancy for other optimizations (like increased per-thread register usage) can lead to higher overall performance [12] [10].

Q2: What are the common factors that limit occupancy?

Several hardware resources can limit the theoretical maximum occupancy of a kernel [12] [10]:

- Register Usage per Thread: Each thread allocates a number of registers. If the total registers used by all threads in a block exceeds the SM's register file capacity, it limits the number of concurrent blocks.

- Shared Memory per Block: The amount of shared memory (

__shared__variables and dynamically allocated memory) required by a block is a limiting factor. If a block uses too much shared memory, fewer blocks can reside on an SM concurrently. - Threads per Block (Block Size): The hardware has a maximum limit on the number of threads and blocks that can be active per SM. A very large block size might prevent enough blocks from being scheduled to achieve full occupancy [10].

- Warps per SM / Blocks per SM: These are hard architectural limits that cap the maximum number of concurrent warps or blocks, regardless of other resources [10].

Q3: How does latency affect performance, and how is it hidden?

Latency is the delay between initiating an operation and its completion. In GPUs, primary latencies are [13]:

- Memory Latency: Hundreds of clock cycles to access global memory.

- Instruction Latency: Clock cycles required for arithmetic operations to complete.

GPUs hide this latency through massive parallelism [12]. When a warp stalls (e.g., on a memory access), the warp scheduler rapidly switches to another eligible warp that has its operands ready. Effective latency hiding requires having sufficient active warps—this is why occupancy is critical [11]. The goal is to always have work available for the SM to execute, ensuring its compute units are never idle.

Q4: What is the relationship between throughput and the other metrics?

Throughput measures the amount of work completed per unit of time (e.g., GFLOP/s for computation, GB/s for memory) [14].

- Relationship: Occupancy and latency hiding are means to achieve high throughput. While high occupancy provides more available warps to hide latency, the ultimate goal is to maximize the throughput of useful work [12]. A kernel can have high occupancy but low throughput if, for example, its memory access patterns are inefficient, or it is limited by the instruction throughput of the SM [15].

Q5: My kernel has high theoretical occupancy but low performance. What could be wrong?

Theoretical occupancy is an upper bound; the achieved occupancy during execution might be lower. Furthermore, high occupancy does not guarantee high performance. Other factors to investigate include [10] [15]:

- Inefficient Memory Access Patterns: Non-coalesced global memory accesses can drastically reduce effective memory bandwidth, becoming the primary performance bottleneck [14] [16].

- Thread Divergence: Within a warp, if threads take different execution paths (due to conditional statements), these paths are executed serially, reducing warp efficiency [16].

- Shared Memory Bank Conflicts: Concurrent accesses to the same shared memory bank by multiple threads in a warp cause serialization, stalling the warp [15].

- Instruction-Bound Kernel: If the kernel performs a high number of arithmetic operations relative to memory accesses, its performance may be limited by the SM's peak instruction throughput, not memory bandwidth [12] [15].

Performance Optimization Experimental Protocols

This section outlines a structured, two-phase methodology for diagnosing and optimizing kernel performance, based on established best practices [17] [13]. The following workflow visualizes the recommended diagnostic journey.

Workflow: A Two-Phase Approach to Kernel Profiling

Phase 1: System-Level Analysis with NVIDIA Nsight Systems

- Objective: Identify system-wide bottlenecks, such as inefficient data transfers between the CPU (host) and GPU (device), or kernel launch overheads [13].

- Experimental Protocol:

- Profile Collection: Run your application using the command:

nsys profile -o output_file ./your_application[13]. - Data Transfer Analysis: In the generated timeline, examine the duration and frequency of data transfers (e.g.,

cudaMemcpy). The goal is to minimize time spent on data movement [13]. - Kernel Overview: Identify which kernels consume the most time. Note their launch configuration (grid and block sizes) [13].

- Profile Collection: Run your application using the command:

- Interpretation & Action:

- If data transfer time is significant relative to kernel computation time, optimization is required. Consider techniques like using pinned host memory or overlapping data transfers with computation using streams [13].

- If kernel runtime dominates, proceed to Phase 2 for in-depth kernel analysis.

Phase 2: Kernel-Level Deep Dive with NVIDIA Nsight Compute

- Objective: Analyze the internal execution of a specific kernel to identify bottlenecks in occupancy, memory access, and instruction throughput [13].

- Experimental Protocol:

- Profile Collection: Run a detailed profile on your target kernel. For a full suite of metrics, use:

ncu --set full -o output_file ./your_application. To collect specific metrics, use the--metricsflag [13]. - Occupancy Analysis: Check the "Scheduler Statistics" and "Occupancy" sections. Compare the achieved occupancy with the theoretical maximum.

- Memory Access Analysis: Key metrics to collect and analyze [13]:

l1tex__t_sectors_pipe_lsu_mem_global_op_ld.sum: Total sectors read from global memory.l1tex__average_t_sectors_per_request_pipe_lsu_mem_global_op_ld.ratio: Average sectors per load request. A value of 4 indicates optimal coalescing [13].

- Warp State Analysis: Examine metrics like "Warp Execution Efficiency" to see the percentage of active threads in a warp. Low efficiency indicates divergence [13].

- Profile Collection: Run a detailed profile on your target kernel. For a full suite of metrics, use:

Quantitative Data from MatMul Kernel Optimization

The following table summarizes the performance gains achieved through iterative optimization of a single-precision matrix multiplication (SGEMM) kernel on an A6000 GPU, progressing from a naive implementation to one approaching cuBLAS performance [14]. This serves as a powerful real-world example of how the metrics discussed can be improved.

Table: Performance Progression of a Custom SGEMM Kernel [14]

| Kernel Optimization Stage | Performance (GFLOP/s) | Performance Relative to cuBLAS |

|---|---|---|

| 1: Naive | 309.0 | 1.3% |

| 2: GMEM Coalescing | 1,986.5 | 8.5% |

| 3: SMEM Caching | 2,980.3 | 12.8% |

| 4: 1D Blocktiling | 8,474.7 | 36.5% |

| 5: 2D Blocktiling | 15,971.7 | 68.7% |

| 6: Vectorized Mem Access | 18,237.3 | 78.4% |

| 9: Autotuning | 19,721.0 | 84.8% |

| 10: Warptiling | 21,779.3 | 93.7% |

| 0: cuBLAS (Reference) | 23,249.6 | 100.0% |

Key Experimental Insights from the MatMul Case Study:

- Impact of Memory Coalescing (Kernel 2): The initial 6x performance jump highlights the critical importance of efficient global memory access patterns. By ensuring adjacent threads access adjacent memory locations, the kernel dramatically reduces the number of required memory transactions, improving throughput [14] [16].

- Impact of Shared Memory Caching (Kernel 3): Moving to a tiled algorithm where threads collaboratively load blocks of data into fast shared memory before computation reduces redundant global memory accesses. This optimization improves data reuse and is a fundamental step for compute-bound kernels [14].

- Advanced Tiling for Arithmetic Intensity (Kernels 4-5): Increasing the tile size (2D blocktiling) processes more data per thread, improving arithmetic intensity (FLOPs per byte transferred). This shifts the performance bottleneck from the memory hierarchy to the compute units, leading to another significant performance doubling [14].

- The Final 15% (Kernels 6-10): The last leg of optimization involves finer-grained techniques like vectorized memory access, autotuning launch parameters, and warp-level tiling to maximize both memory and instruction throughput, closing the gap with the highly optimized cuBLAS library [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Software & Metrics

This table details key software tools and hardware metrics that are indispensable for researchers conducting GPU kernel optimization.

Table: Essential Tools and Metrics for Kernel Optimization Research

| Tool / Metric | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| NVIDIA Nsight Systems [13] | Profiling Tool | System-wide performance analysis. Visualizes CPU/GPU timelines, data transfers, and kernel execution. | Identifying high-level bottlenecks, ensuring the GPU is fully utilized, and verifying that data pipeline overheads are minimized. |

| NVIDIA Nsight Compute [13] | Profiling Tool | Detailed kernel performance analysis. Provides metrics on occupancy, memory efficiency, and warp execution. | Pinpointing exact low-level inefficiencies within a kernel, essential for guiding micro-optimizations. |

| NVIDIA Compute Sanitizer [13] | Debugging Tool | Detects memory access errors, race conditions, and synchronization issues in CUDA kernels. | Ensuring the correctness of custom kernels, which is a prerequisite for meaningful performance analysis. |

| Theoretical Occupancy [10] | Performance Metric | The upper limit of occupancy determined by kernel launch configuration and GPU hardware limits. | Used for initial configuration tuning and understanding the performance headroom. |

| Achieved Occupancy [10] [13] | Performance Metric | The average number of active warps per SM during kernel execution, measured by hardware counters. | A ground-truth measure of latency-hiding capability. Guides optimization efforts more accurately than theoretical occupancy. |

| Memory Transactions per Request [13] | Performance Metric | Measures the efficiency of global memory accesses. A value of 4 indicates perfectly coalesced access. | Directly quantifies the effectiveness of memory access patterns. A key metric for memory-bound kernels. |

| Warp Execution Efficiency [13] | Performance Metric | The percentage of active threads in a warp during execution. Low values indicate warp divergence. | Diagnosing performance losses due to control flow (if/else, loops) within kernels. |

Troubleshooting Common Performance Problems

This section provides a diagnostic guide for common performance issues, linking symptoms to probable causes and potential solutions.

Table: Troubleshooting Guide for Kernel Performance Issues

| Observed Symptom | Potential Root Cause | Diagnostic Method | Recommended Mitigation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low Achieved Occupancy | High register usage per thread; Excessive shared memory allocation per block; Suboptimal block size [12] [10]. | Use Nsight Compute to check occupancy-limited-by reason and resource usage. | Use __launch_bounds__ to limit register usage; Reduce shared memory footprint; Experiment with different block sizes (e.g., 128, 256) [12]. |

| Poor Global Memory Throughput | Non-coalesced memory accesses; Unfavorable memory access patterns (e.g., strided) [14] [16]. | Use Nsight Compute to check "Sectors Per Request" metric. A value below 4 indicates uncoalesced access [13]. | Restructure data access patterns for contiguous thread access; Use shared memory as a programmer-managed cache to batch and reorder accesses [14]. |

| Low Warp Execution Efficiency | Thread divergence within warps due to conditionals (if/else) [16]; Resource-based serialization (e.g., shared memory bank conflicts) [15]. | Use Nsight Compute to check "Warp Execution Efficiency" and "Divergent Branch" metrics [13]. | Restructure algorithms to minimize branching on a per-warp basis; Pad shared memory arrays to avoid bank conflicts [15]. |

| Unexpected Register Spilling | The compiler has allocated more live variables than available registers, forcing some to "spill" to local memory (which resides in global memory) [12] [15]. | Check compiler output for "spill stores" and "spill loads" [12]. | Reduce register pressure by breaking down complex expressions; Use __launch_bounds__; Avoid dynamic indexing of large arrays declared in a kernel [12]. |

| Kernel Performance Varies with Input Size | Tile quantization effects: the grid launch size does not evenly divide the problem size, leaving some SMs underutilized [14]. | Check if matrix dimensions are not multiples of the tile size used. | Use a guard in the kernel to check bounds (if (x < M && y < N)) and adjust launch bounds to cover the entire problem space [14]. |

Foundations of GPU Memory Hierarchy

For researchers leveraging GPU acceleration in computational drug discovery, understanding memory hierarchy is crucial for optimizing kernel execution. This architecture is a pyramid of memory types, each with distinct trade-offs between speed, capacity, and scope.

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of the primary memory types used in CUDA programming:

| Memory Type | Physical Location | Speed (Relative) | Capacity | Scope |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Register | On-chip (per core) | Fastest (1x latency unit) [18] | Very Limited (~8KB per SM) [19] | Single Thread |

| Shared Memory | On-chip (per SM) | Very Fast | Limited (~16KB per SM) [19] | All threads in a Block |

| Local Memory | Off-chip (DRAM) | Slow | Large | Single Thread |

| Global Memory | Off-chip (DRAM) | Slow (100+ latency units) [18] | Very Large (GBs) [19] | All threads & Host |

| Constant Memory | Off-chip (DRAM) | Slow, but cached for fast read [19] | Small (~64 KB) [19] | All threads (Read-Only) |

| L1/L2 Cache | On-chip & Off-chip | Fast (Varies by level) | Limited | Hardware Managed |

This hierarchy exists to hide memory latency and maximize memory bandwidth, which are primary bottlenecks in parallel computing. The GPU tolerates latency by switching execution between thousands of lightweight threads when one warp stalls on a memory request [17]. Effective use of fast, on-chip memories like registers and shared memory is therefore key to performance.

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship and data flow between these critical memory types and the GPU's computational units:

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

This section addresses common pitfalls and questions researchers face when configuring GPU kernel memory.

FAQ 1: My kernel is slower than the CPU version for small problem sizes. Why?

- Problem: For small datasets, the overhead of transferring data to the GPU's global memory and the kernel launch itself can outweigh the parallel computation benefits. This is often seen with matrix sizes below 500x500 [19].

- Solution:

- Assess Data Transfer: Profile your application with NVIDIA Nsight Systems to quantify data transfer time (

cudaMemcpy) versus kernel execution time. Minimize transfers by batching data or using managed memory (cudaMallocManaged) where appropriate [17] [20]. - Increase Arithmetic Intensity: For smaller problems, design your kernel to perform more computations per data element fetched from memory, moving the workload from being memory-bound to compute-bound.

- Assess Data Transfer: Profile your application with NVIDIA Nsight Systems to quantify data transfer time (

FAQ 2: How can I diagnose and fix poor global memory access patterns?

- Problem: Non-coalesced global memory access is a major performance killer. This occurs when threads in a warp access scattered memory locations, resulting in multiple slow transactions [20].

- Solution:

- Diagnose with Nsight Compute: Use the

l1tex__t_sectors_pipe_lsu_mem_global_op_ld.sumandl1tex__average_t_sectors_per_request_pipe_lsu_mem_global_op_ld.ratiometrics. A ratio of 4 sectors per request indicates optimal, coalesced access [20]. - Ensure Coalesced Access: Structure your data and thread indexing so that consecutive threads access consecutive memory addresses. Prefer array-of-structures for sequential access and structure-of-arrays for random access.

- Diagnose with Nsight Compute: Use the

FAQ 3: What does "CUDA Out of Memory" mean and how can I resolve it?

- Problem: The GPU's global memory is exhausted. This is common when processing large datasets, like molecular dynamics trajectories or high-throughput screening results [21].

- Solution:

- Check Current Usage: Use

nvidia-smito monitor memory usage in real-time [21]. - Memory Management:

- Use an RMM Pool to pre-allocate memory, which drastically reduces allocation overhead in workflows with many small operations [22].

- Implement Automatic Spilling: For Dask-cuDF workflows, enable spilling to host memory when GPU memory is full [22].

- Batch Processing: Split your data into smaller chunks that fit into GPU memory and process them sequentially.

- Optimize Allocation: If running multiple services on one GPU (e.g., an embedding service and a database), use dependency-based startup and automatic memory allocation to prevent conflicts [21].

- Check Current Usage: Use

FAQ 4: When should I use shared memory vs. registers?

- Problem: Misallocating data between the fastest memory types leads to suboptimal performance.

- Solution: Use the following decision framework:

- Use Registers for thread-private variables that are accessed frequently and have a lifetime matching the kernel. They are the fastest option but are a scarce resource; high register usage can lower occupancy by limiting the number of concurrent warps [19].

- Use Shared Memory as a software-managed cache for data reused by multiple threads within the same block. It is ideal for stencils, tiles in matrix multiplication, and intermediate results in reduction operations [6] [19]. Kernel fusion techniques can use shared memory to hold intermediate data, avoiding round trips to global memory [6].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

This section provides a reproducible methodology for profiling and optimizing memory usage in your GPU kernels, directly supporting thesis research on kernel execution configuration.

Protocol: Two-Phase Profiling for Memory Performance

This protocol uses NVIDIA's tools to systematically identify and diagnose memory-related bottlenecks [20].

Phase 1: System-Level Analysis with Nsight Systems

- Objective: Identify high-level bottlenecks like excessive data transfers or kernel launch overhead.

- Procedure:

nsys profile -o output_file ./your_application - Data Analysis: In the generated timeline, look for:

- Long durations of

cudaMemcpyoperations relative to kernel runtime. - Large gaps between kernel launches indicating CPU-side overhead.

- Long durations of

- Outcome: Decide whether to focus on reducing transfer overhead or optimizing the kernel itself.

Phase 2: Kernel-Level Deep Dive with Nsight Compute

- Objective: Obtain detailed metrics on memory throughput, cache efficiency, and warp execution.

- Procedure:

ncu --set full -o kernel_profile ./your_application - Key Metrics & Interpretation:

Metric Target Value Interpretation l1tex__average_t_sectors_per_request_pipe_lsu_mem_global_op_ld.ratio~4 Indicates well-coalesced global memory loads [20]. l1tex__data_pipe_lsu_wavefronts_mem_shared_op_ld.sum-- High value indicates active use of shared memory. sm__warps_active.avg.pct_of_peak_sustained_activeHigh % Low values indicate warp stalls, often due to memory latency. l1tex__t_sectors_pipe_lsu_mem_global_op_ld.sumMinimize Total global load transactions; lower is better.

Protocol: Autotuning Shared Memory and Register Usage

Manual optimization can be time-consuming. This protocol outlines using autotuning frameworks to find optimal configurations [6].

Define the Search Space: Identify the parameters to tune. These often include:

- Block size (e.g., from 32 to 512 threads in powers of two).

- Shared memory usage per block (e.g., 4KB to 48KB).

- Loop unrolling factors and tiling dimensions.

Select an Autotuning Framework: Frameworks like the Kernel Tuning Toolkit (KTT) can automate the search process [6].

Run the Autotuner: The framework will compile and benchmark the kernel with hundreds of parameter combinations.

Validate the Result: The framework outputs the best-performing configuration. Re-run this configuration to ensure stability and correctness before deploying it in production research code.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following software tools and libraries are essential "reagents" for any research project focused on optimizing GPU kernel performance.

| Tool / Library | Function | Use Case in Research |

|---|---|---|

| NVIDIA Nsight Systems | System-wide performance profiler | Provides an initial "triage" view to identify major bottlenecks like data transfer overhead in a simulation pipeline [20]. |

| NVIDIA Nsight Compute | Detailed kernel profiler | Offers deep, low-level metrics on memory coalescing and warp efficiency, crucial for iterative kernel optimization [20]. |

| NVIDIA Compute Sanitizer | Runtime error checking tool | Detects memory access violations and race conditions in kernels, ensuring correctness during algorithm development [20]. |

| Kernel Tuning Toolkit (KTT) | Autotuning framework | Automates the search for optimal kernel parameters (block size, memory tiling), accelerating the research cycle [6]. |

| RAPIDS RMM (RAPIDS Memory Manager) | Pool-based memory allocator | Reduces allocation latency in workflows with many operations (e.g., analyzing large genomic sequences), improving overall throughput [22]. |

| CUDA C++ Best Practices Guide | Official programming guide | The definitive reference for understanding fundamental optimization concepts and patterns [17]. |

Common Design Pitfalls in Kernel Execution Configuration

Frequently Asked Questions

Why is my GPU kernel significantly slower than my CPU implementation? This is often due to common initial mistakes such as including host-to-device data transfer times in your measurements, using a poorly configured kernel launch that doesn't utilize all GPU cores, or having inefficient memory access patterns within the kernel that lead to uncoalesced global memory reads/writes [23] [24]. Ensure you are only timing the kernel execution itself and review the guidelines below.

How do I choose the right number of blocks and threads for my kernel? There is no single perfect answer, as the optimal configuration depends on your specific algorithm and GPU hardware. A good starting point is to aim for a kernel launch with enough threads to fill the GPU, which is roughly 2048 threads per Streaming Multiprocessor (SM) on many GPUs [25]. Performance is often good for block sizes that are powers of two, such as 128, 256, or 512 threads per block [25]. The key is to experiment with different configurations and use a profiler to find the best one for your task.

What does "uncoalesced memory access" mean and why is it bad? Coalesced memory access occurs when consecutive threads in a warp access consecutive memory locations in a single transaction. Uncoalesced access happens when threads access memory in a scattered or non-sequential pattern, forcing the GPU to issue multiple separate memory transactions. This can severely degrade performance—by a factor of 10 or more [23]. The CUDA Programming Guide provides detailed rules and examples for achieving coalesced access.

My kernel uses a large data structure. Should each thread make its own copy? No, this is a common and costly misconception. You should not make a copy of a large data structure for each thread [25]. Instead, place a single copy in global memory and have all threads read from it directly. If threads only read the data, this is straightforward. If they need to modify it, you must carefully design how and where the results are written to avoid data corruption, typically by having each thread write to a unique, pre-allocated location in an output array [25].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inefficient Kernel Launch Configuration

A kernel launch that is too small will leave GPU resources idle, while one that is overly large can introduce diminishing returns and overhead. The goal is to find a balance that maximizes occupancy and workload distribution.

Diagnosis:

- Check the launch configuration of your kernel (the grid and block dimensions).

- Use a profiling tool like NVIDIA Nsight Systems to analyze GPU utilization. Low utilization often points to an insufficient number of threads.

Resolution:

- Methodology: Use a heuristic-based approach combined with empirical testing.

- Determine a Starting Point: Use the

cudaOccupancyMaxPotentialBlockSizefunction, which provides a suggested block size to maximize occupancy [25]. - Calculate Grid Size: Based on your total workload (e.g.,

Ndata elements) and your chosen block size (BLOCK_SIZE), calculate the grid size as(N + BLOCK_SIZE - 1) / BLOCK_SIZEto ensure all elements are processed. - Establish a Testing Protocol: Create a benchmark that runs your kernel with a range of different block sizes (e.g., 64, 128, 256, 512, 1024) while keeping the total workload constant.

- Measure and Compare: Use precise timing methods like

cudaEventRecord()to measure the kernel's execution time for each configuration [24]. Run each configuration multiple times to account for system noise.

- Determine a Starting Point: Use the

- Experimental Data: The table below shows how kernel performance can vary with different block sizes on two GPU architectures, processing a fixed total problem size [26]. The key metric is time per cell, where lower is better.

| GPU Architecture | Patch Size & Strategy | Performance (ns/cell) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| NVIDIA A6000 | 16³ patches, single kernel (Baseline) | 0.45 | Optimal, large-batch launch |

| 40³ patches, one kernel per patch | 0.53 | ~18% slower due to launch overhead | |

| NVIDIA H100 | 16³ patches, single kernel (Baseline) | 0.19 | Optimal, large-batch launch |

| 40³ patches, one kernel per patch | 0.28 | ~47% slower due to launch overhead | |

| 16³ patches, bunched in 512 patches | 0.20 | Near-optimal, minimizes overhead |

The following workflow summarizes the iterative process of optimizing kernel launch parameters:

Issue 2: Excessive Kernel Launch Overhead

Launching a GPU kernel involves non-zero overhead from the driver and system. When an application launches thousands of small, independent kernels, this overhead can dominate the total execution time, leading to poor performance.

Diagnosis:

- Your application logic involves launching a very large number of small kernels.

- Profiling shows low GPU compute utilization with many gaps between kernel executions.

Resolution:

- Methodology: Implement kernel fusion or batching to amortize the launch cost over more work.

- Identify Independent Work: Analyze your algorithm to find small, independent tasks (e.g., processing individual patches or elements) that are currently handled by separate kernels.

- Design a Batched Kernel: Create a new, larger kernel that can process multiple of these independent tasks within a single launch. This can be done by extending the kernel's grid or having each thread block process multiple items.

- Manage Task Queue: If tasks are generated dynamically, maintain a task queue on the GPU device. When the queue reaches a certain size (a "bunch"), launch a single kernel to process all tasks in the bunch [26].

- Experimental Protocol:

- Baseline: Time your application launching one kernel per task.

- Intervention: Time the modified application that batches

Ntasks per kernel launch. - Analysis: Plot the total execution time versus the batch size (

N). You will typically see significant improvement asNincreases, with benefits leveling off after a point.

Issue 3: Poor Global Memory Access Patterns

GPUs are optimized for contiguous, aligned memory accesses by threads in a warp. When memory access is uncoalesced, it forces serialized transactions to global memory, creating a major performance bottleneck.

Diagnosis:

- Profiler tools (e.g., NVIDIA Nsight Compute) report low memory throughput and a high rate of uncoalesced accesses.

- Kernel performance is poor despite high theoretical arithmetic intensity.

Resolution:

- Methodology: Restructure your code and data to enable memory coalescing.

- Data Layout Transformation: If your data is stored in an Array of Structures (AoS), consider transforming it to a Structure of Arrays (SoA). For example, instead of

struct Particle {float x, y, z;} parts[N];, usestruct Particles {float x[N], y[N], z[N];}. This ensures that when threadiaccessesx[i], the accesses from all threads in the warp are to contiguous memory locations. - Shared Memory Staging: For complex, non-sequential access patterns (e.g., stencils), a common technique is to load data from global memory into fast, on-chip shared memory in a coalesced manner. Threads can then perform their computations with random access on the data in shared memory, which has much lower latency.

- Data Layout Transformation: If your data is stored in an Array of Structures (AoS), consider transforming it to a Structure of Arrays (SoA). For example, instead of

Issue 4: Underutilizing Shared Memory

Global memory is slow, while shared memory is a fast, software-managed cache on each GPU streaming multiprocessor. Failing to use it for data reused by multiple threads within a block forces repeated, slow accesses to global memory.

Diagnosis:

- Your kernel repeatedly reads from the same regions of global memory.

- Profiling shows high global memory latency and low shared memory utilization.

Resolution:

- Methodology: Use shared memory as a programmer-managed cache.

- Identify Reused Data: Locate data elements within your kernel that are read multiple times by different threads in the same thread block.

- Allocate Shared Memory: Declare a shared memory array in your kernel using the

__shared__qualifier. - Collaborative Data Loading: Have the threads in a block collaborate to load data from global memory into the shared memory array. This loading phase should be designed to be coalesced.

- Synchronize: Use

__syncthreads()after loading data to ensure all threads in the block have finished writing to shared memory before any thread begins reading from it. - Perform Computation: Run the core computation using the data from fast shared memory.

Example Code Snippet:

- Experimental Protocol: Compare the execution time of your original kernel (direct global memory access) against the optimized version that uses shared memory for data reuse. The speedup can be substantial, often 2x or more depending on the access pattern [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit

| Tool / Technique | Function | Use Case in Kernel Configuration |

|---|---|---|

| NVIDIA Nsight Systems | System-wide performance profiler | Identifies if low GPU utilization is caused by poor kernel launch configuration or excessive launch overhead [27] [24]. |

| NVIDIA Nsight Compute | Detailed kernel-level profiler | Analyzes metrics for a specific kernel, including memory access patterns (coalescing), shared memory usage, and pipeline statistics [27]. |

cudaOccupancyMaxPotentialBlockSize |

API function | Provides a data-driven heuristic for selecting a block size that maximizes theoretical occupancy on the current GPU [25]. |

cudaEventRecord() |

Precise timing API | Used to accurately measure kernel execution time during experimental tuning of launch parameters, avoiding host-side clock inaccuracies [24]. |

| Kernel Fusion / Batching | Code optimization strategy | Amortizes kernel launch overhead by combining multiple small computational tasks into a single, larger kernel launch [26]. |

Shared Memory (__shared__) |

On-chip, programmer-managed cache | Dramatically reduces effective memory latency for data reused within a thread block [24]. |

Leveraging GPU Acceleration in Drug Discovery Workflows

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My molecular dynamics simulation is running slower on a GPU than on a CPU. What could be the cause?

This often stems from initialization overhead or suboptimal execution configuration. When a CUDA application runs for the first time, there is a significant one-time initialization cost. For short-running scripts, this overhead can make the GPU seem slower. Ensure your simulation runs for a sufficient number of iterations (e.g., 5000 instead of 500) to amortize this cost [28]. Furthermore, small batch sizes or kernel launch overhead can cripple performance. Using CUDA Graphs to group multiple kernel launches into a single, dependency-defined unit can drastically reduce this overhead and improve overall runtime [29].

Q2: I am encountering "CUDA error: an illegal memory access was encountered" during backpropagation. How can I resolve this?

An illegal memory access typically indicates that a kernel is trying to read from or write to an invalid GPU memory address. This is usually a code-level issue, not a hardware failure. First, use debugging tools like cuda-memcheck to identify the precise line of code causing the error. In a multi-GU system, if the error follows a specific physical GPU when swapped between slots, a hardware defect or a power delivery issue is possible. Check your system logs for GPU-related errors and ensure your power supply is adequately sized for all GPUs, accounting for power spikes above the TDP rating [30].

Q3: What is the primary benefit of using CUDA Graphs in drug discovery workflows?

The main benefit is the significant reduction in kernel launch overhead. In traditional CUDA execution, launching many small kernels sequentially creates substantial CPU overhead. CUDA Graphs capture a whole workflow of kernels and their dependencies into a single unit. When executed, this graph launches with minimal CPU involvement. This is particularly beneficial for iterative molecular dynamics simulations, where the same sequence of kernels is run repeatedly. Case studies have demonstrated that this technique can lead to performance improvements of up to 2.02x in key workloads [29].

Q4: When should I consider using a multi-GPU setup for simulations with software like AMBER or GROMACS?

A multi-GPU setup is advantageous when you are working with very large molecular systems that exceed the memory capacity of a single GPU, or when you need to dramatically decrease simulation time for high-throughput screening. Applications like AMBER, GROMACS, and NAMD are optimized for multi-GPU execution, distributing the computational load across several devices. This parallelization can lead to a near-linear speedup for appropriately sized problems, allowing researchers to simulate larger systems or more candidate molecules in less time [31].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor GPU Utilization in Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Symptoms: Low GPU utilization percentages (e.g., consistently below 50%), slower-than-expected simulation times, high CPU usage while GPU is idle.

Diagnosis and Resolution:

- Check for Serial Bottlenecks: Use profiling tools like NVIDIA Nsight Systems to identify kernels that are running sequentially. Optimize or fuse these kernels to create a more parallel execution flow.

- Optimize Throughput with Multiple Simulations: To mask serial bottlenecks, schedule multiple independent simulations on the same GPU. This ensures the GPU is continuously fed with work, improving overall utilization and throughput [29].

- Leverage Mapped Memory: For workflows with frequent small data transfers, use mapped (pinned) memory to eliminate explicit data transfer delays and enable better overlap of computation and communication [29].

Issue 2: GPU Kernel Launch Timeouts and System Instability

Symptoms: Kernels fail with a "launch timed out" error, system becomes unresponsive during heavy computation, other processes are starved of resources.

Diagnosis and Resolution:

- Check Kernel Runtime Limit: On display GPUs (e.g., GeForce series), the operating system enforces a kernel execution time limit to maintain a responsive GUI. Use

deviceQueryfrom the CUDA samples to check this limit. For headless servers dedicated to computation, disable the graphical desktop (X server) to remove this limitation [30]. - Inspect Power and Thermal Management:

- Power Supply: Ensure your power supply unit (PSU) is not only rated for the total Thermal Design Power (TDP) of all components but can also handle instantaneous power spikes, which can be 40% above TDP. Avoid using power splitters or daisy-chaining PCIe power cables for high-end GPUs [30].

- Thermals: Monitor GPU core and memory junction temperatures during computation. Use tools like

nvidia-smito log temperatures. Persistent high temperatures can cause throttling or instability. Improve case airflow or consider a workstation with advanced cooling solutions [31].

Performance Data and Hardware Selection

| MD Software | Recommended GPU (Performance Priority) | Recommended GPU (Budget/Capacity) | Key Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| AMBER | NVIDIA RTX 6000 Ada | NVIDIA RTX 4090 | The RTX 6000 Ada's 48 GB VRAM is ideal for the largest simulations. The RTX 4090 offers excellent performance for smaller systems. |

| GROMACS | NVIDIA RTX 4090 | NVIDIA RTX 5000 Ada | Benefits from high raw processing power and CUDA core count, where the RTX 4090 excels. |

| NAMD | NVIDIA RTX 6000 Ada | NVIDIA RTX 4090 | Optimized for NVIDIA GPUs; performance scales with CUDA cores and memory bandwidth. |

| Optimization Technique | Application Context | Reported Performance Gain |

|---|---|---|

| CUDA Graphs | Desmond MD Engine (Schrödinger) | Up to 2.02x speedup in key workloads |

| C++ Coroutines | Desmond MD Engine (Schrödinger) | Improved GPU utilization by overlapping computations |

| Dedicated Multi-Node Training (DGX Cloud) | COATI Model Training (Terray Therapeutics) | Reduced training time from 1 week to 1 day; 4x improved resource utilization |

| Kernel Fusion | General GPU Computing | Up to 2.61x speedup over unfused kernel sequences |

Experimental Protocols for Kernel Optimization

Protocol 1: Implementing CUDA Graphs for Iterative MD Simulations

Objective: To reduce kernel launch overhead in a repetitive simulation workflow by capturing and executing it as a CUDA Graph.

Methodology:

- Initial Profile: Use a profiler to record the default execution of your simulation iteration, noting the number and duration of kernel launches.

- Graph Capture: Isolate the sequence of kernel launches and memory operations that constitute a single simulation step. Enclose this section with

cudaStreamBeginCaptureandcudaStreamEndCapture. - Instantiate Graph: Call

cudaGraphInstantiateto create an executable graph from the captured sequence. - Graph Execution: Replace the loop of individual kernel launches with a loop that executes the instantiated graph using

cudaGraphLaunch. - Validation and Benchmarking: Verify that the results are identical to the non-graph version. Measure the performance difference in simulations per day or total runtime for a fixed number of iterations [29].

Protocol 2: Autotuning Kernel Execution Configuration

Objective: To systematically determine the optimal execution configuration (block size, grid size) for a CUDA kernel.

Methodology:

- Define Search Space: Identify the tunable parameters for your kernel, typically the number of threads per block (block size). Create a list of candidate values (e.g., 32, 64, 128, 256, 512, 1024).

- Isolate the Kernel: Ensure the kernel can be launched and timed independently of the rest of your application.

- Benchmarking Loop: For each candidate configuration, run the kernel multiple times (e.g., 100 iterations) and calculate the average execution time. Use CUDA events (

cudaEventRecord) for precise timing. - Result Validation: For each configuration, verify the kernel output is correct to ensure optimization does not break functionality.

- Selection: Choose the execution configuration that yields the shortest average kernel runtime. Frameworks like the Kernel Tuning Toolkit (KTT) can automate this process [6].

Workflow Optimization Diagrams

MD Workflow: Native vs CUDA Graph

Multi-GPU Scaling Logic

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

| Resource Name | Type | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| NVIDIA BioNeMo [32] [33] | Cloud Service & Framework | A platform for developing and deploying generative AI models on biomolecular data (proteins, DNA, small molecules), offering pre-trained models and customization tools. |

| NVIDIA Clara for Drug Discovery [32] | Application Framework | A comprehensive platform that combines AI, simulation, and visualization to support various stages of drug design and development. |

| CUTLASS [34] | CUDA C++ Template Library | Enables custom implementation and optimization of linear algebra operations (like GEMM), often used for kernel fusion and writing low-level PTX for peak performance. |

| CUDA Graphs [29] | Programming Model | Reduces CPU overhead and improves performance by grouping multiple kernel launches and dependencies into a single, executable unit. |

| AMBER, GROMACS, NAMD [31] | Molecular Dynamics Software | Specialized applications for simulating the physical movements of atoms and molecules, heavily optimized for GPU acceleration to study protein folding, ligand binding, and more. |

Strategic Optimization Methods and Real-World Applications in Biomedical Research

Frequently Asked Questions

1. How do I choose the optimal block size for my kernel?

The optimal block size is a balance between hardware constraints and performance tuning. The number of threads per block should be a multiple of the warp size (32 on all current hardware) and typically falls within the 128-512 range for best performance. You can use the CUDA Occupancy API (cudaOccupancyMaxPotentialBlockSize) to heuristically calculate a block size that achieves maximum occupancy, which is a good starting point for further tuning [35].

2. My kernel is using too many hardware registers, leading to register spilling. How can I improve performance?

Starting with CUDA 13.0, you can enable shared memory register spilling. This feature instructs the compiler to prioritize using on-chip shared memory for register spills instead of off-chip local memory, which reduces access latency and L2 pressure. Enable it by adding the pragma asm volatile (".pragma \"enable_smem_spilling\";"); inside your kernel function [36].

3. What are the hard limits that constrain my grid and block dimensions? CUDA programming guides specify hard limits that your kernel launch configuration must adhere to [35]:

- Threads per block: Maximum of 1024 threads for Compute Capability 2.x and later.

- Block dimensions: Maximum sizes of [1024, 1024, 64].

- Register limits: The total registers per block cannot exceed architecture-dependent limits (e.g., 64k for Compute 5.3).

- Shared memory: Limited to 48kb/96kb for Compute 2.x-6.2/7.0.

4. What is the relationship between block size and occupancy? Occupancy is the ratio of active warps on a streaming multiprocessor (SM) to the maximum possible active warps. Higher occupancy helps hide memory and instruction pipeline latency. The block size you choose directly impacts occupancy, as it determines how many thread blocks can reside concurrently on an SM. The goal is to have enough active warps to keep the GPU busy [35].

5. Are there automated tools to help find the best execution configuration? Yes, several tools can assist [35] [37]:

- CUDA Runtime API: The

cudaOccupancyMaxPotentialBlockSizefunction suggests a block size for maximum occupancy. - Profiling Tools: NVIDIA Nsight Compute is essential for guiding optimization efforts by identifying bottlenecks.

- Libraries: CuPy, for instance, offers utilities like

MaximizeOccupancyandOccupancyMaximizeBlockSizefor automated parameter tuning.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Poor Kernel Performance Due to Register Spilling

Register spilling occurs when a kernel requires more hardware registers than are available, forcing the compiler to move variables into slower local memory (in global memory). This significantly impacts performance [36].

Diagnosis:

- Compile your code with

nvcc -Xptxas -v -arch=sm_XX. The output will show spill stores and loads, as well as the cumulative stack size. - Use Nsight Compute to profile the kernel and identify if local memory accesses are a bottleneck.

Resolution: Enable Shared Memory Register Spilling This optimization uses faster, on-chip shared memory for spills [36].

- Modify Your Kernel Code: Add the enablesmemspilling pragma via inline assembly at the beginning of your kernel.

- Verify the Compilation Output: Recompile with

nvcc -Xptxas -v -arch=sm_XX. A successful application of the optimization will show0 bytes spill storesand0 bytes spill loads, while thesmem(shared memory) usage will increase.

Experimental Protocol & Results: The following methodology and results are adapted from NVIDIA's testing of this feature [36]:

| Step | Action | Observed Metric (via -Xptxas -v) |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Baseline Compilation | Compile without pragma. | 176 bytes stack frame, 176 bytes spill stores, 176 bytes spill loads |

| 2. Apply Optimization | Recompile with enable_smem_spilling pragma. |

0 bytes stack frame, 0 bytes spill stores, 0 bytes spill loads, 46080 bytes smem |

Table 1: Performance Improvement with Shared Memory Spilling Enabled [36]

| Performance Metric | Without Optimization | With Optimization | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Duration [us] | 8.35 | 7.71 | 7.76% |

| Elapsed Cycles [cycle] | 12477 | 11503 | 7.8% |

| SM Active Cycles [cycle] | 218.43 | 198.71 | 9.03% |

Issue: Suboptimal Grid and Block Dimensions

Choosing the wrong grid and block dimensions can lead to low occupancy and underutilized GPU resources.

Diagnosis:

- Use the CUDA Occupancy API to calculate theoretical occupancy for your current configuration.

- Profile with Nsight Compute to see the achieved occupancy and SM utilization.

Resolution: A Systematic Tuning Methodology

- Determine Initial Configuration: Use the

cudaOccupancyMaxPotentialBlockSizefunction to get a suggested block size and minimum grid size for a full device launch [35]. - Calculate the Actual Grid Size: Based on your data size and the suggested block size.

- Empirical Tuning: Treat the API's suggestion as a starting point. Benchmark your kernel with different block sizes (e.g., 128, 256, 512, 1024) that are round multiples of the warp size (32). The optimal size depends on your specific kernel and hardware [35] [37].

Experimental Protocol for Block Size Tuning:

Issue: Kernel Fails to Launch

The kernel launch fails, often due to exceeding hardware resources.

Diagnosis: Check that your kernel launch configuration does not violate any of the hard limits for your GPU's compute capability [35].

Resolution: Consult the CUDA Programming Guide for your specific architecture. Reduce the number of threads per block, the amount of shared memory per block, or refactor your kernel to use fewer registers.

Research Reagent Solutions

| Tool / Library | Function in Kernel Optimization Research |

|---|---|

| CUDA Toolkit | Provides the core compiler (nvcc), profiling tools, and the Occupancy API for direct configuration tuning and analysis [35]. |

| Nsight Compute | An advanced kernel profiler that provides detailed hardware performance counters. Essential for identifying bottlenecks related to memory, compute, and execution configuration [17]. |

| cuDNN | A GPU-accelerated library for deep neural networks. Its highly tuned kernels serve as a performance benchmark and a practical alternative to custom kernel development for common operations [38]. |

| Triton | An open-source Python-like language and compiler for writing efficient GPU kernels. Useful for researchers to develop and test custom kernels without deep CUDA expertise [39]. |

| ThunderKittens | A library of highly optimized kernels and templates for modern AI workloads, providing reference implementations for performance-critical operations [40]. |

Experimental Workflow for Kernel Configuration Tuning

The following diagram illustrates a systematic, iterative workflow for optimizing kernel execution configuration, integrating the troubleshooting guides and concepts detailed above.

Diagram: Iterative Kernel Configuration Tuning Workflow

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What exactly is "memory coalescing" in CUDA and why is it critical for performance?

Memory coalescing is a hardware optimization where memory accesses from multiple threads in a warp are combined into a single, consolidated transaction to global memory [41] [42]. This is crucial because global memory has high latency and limited bandwidth. When accesses are coalesced, the GPU can fully utilize its memory bandwidth, transferring large chunks of contiguous data in one operation. Non-coalesced access forces the hardware to issue many small, separate transactions for the same amount of data, leading to significant performance degradation. In real-world tests, uncoalesced memory access can be over 3x slower than optimized, coalesced access [42].

Q2: How can I identify if my kernel has non-coalesced memory accesses?

You can identify non-coalesced accesses using NVIDIA's profiling tools. In NVIDIA Nsight Compute, key metrics to check include [43] [20]:

l1tex__t_sectors_pipe_lsu_mem_global_op_ld.sumandl1tex__t_sectors_pipe_lsu_mem_global_op_st.sum: These show the total number of memory sectors loaded from or stored to global memory. Higher values indicate more transactions and potentially less coalescing.l1tex__average_t_sectors_per_request_pipe_lsu_mem_global_op_ld.ratio: This metric indicates the average number of sectors per memory request. An ideal value is 4 sectors per request, signifying optimal coalescing [20]. A lower ratio suggests that your memory transactions are not fully utilizing the available bandwidth.

Q3: In a 2D array like a matrix, should threads access data row-by-row or column-by-column to achieve coalescing?

Threads should access data row-by-row if the matrix is stored in row-major order (which is standard in C/C++) [41]. This ensures that consecutive threads within a warp access consecutive memory addresses. For example, if thread 0 accesses element (0,0), thread 1 accesses (0,1), and thread 2 accesses (0,2), these accesses can be coalesced. In contrast, column-by-column access (thread 0: (0,0), thread 1: (1,0), thread 2: (2,0)) results in strided access patterns that are non-contiguous and cannot be coalesced, severely harming performance [41].

Q4: Does memory coalescing still matter on modern GPU architectures beyond Fermi and Kepler?

Yes, absolutely. While modern architectures (Compute Capability 6.0 and newer) have more sophisticated memory systems with sectoring that improves the efficiency of smaller accesses, coalescing remains a fundamental best practice for performance [41] [44]. Failing to coalesce memory transactions can still result in a significant performance penalty—up to a 2x performance hit on some architectures [41]. Efficient memory access patterns are essential for achieving peak bandwidth.

Q5: What is the relationship between shared memory and global memory coalescing?

Shared memory is a powerful tool for enabling coalesced global memory access. The typical optimization strategy is a two-stage process [43] [45]:

- Coalesced Load/Store to Shared Memory: Have threads in a block cooperatively load data from global memory into shared memory in a coalesced manner. This means organizing the data reads and writes so that threads in a warp access contiguous global memory addresses.

- Data Processing from Shared Memory: Once the data is in shared memory, threads can access it as needed, even if those access patterns are random or uncoalesced. Since shared memory is on-chip and has extremely low latency, these non-sequential accesses are much less costly.

This technique is fundamental to optimizations like tiling for matrix multiplication and convolution [45].

Performance Impact of Memory Access Patterns

The table below summarizes the characteristics and performance impact of different global memory access patterns.

| Access Pattern | Description | Efficiency | Performance Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coalesced [43] [42] | Consecutive threads access consecutive memory addresses. | High (Optimal) | Best performance. Achieves near-peak memory bandwidth. |

| Strided [43] | Threads access memory with a constant, non-unit stride (e.g., every nth element). | Medium to Low | Wastes bandwidth; performance degrades as stride increases. |

| Random [43] | Threads access memory at unpredictable, scattered addresses. | Very Low | Worst performance. Transactions are serialized, severely underutilizing bandwidth. |

Experimental Protocol: Analyzing and Optimizing Memory Coalescing

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for profiling a CUDA kernel, identifying non-coalesced memory access bottlenecks, and applying optimizations, with matrix multiplication as a case study.

1. Research Reagent Solutions (Essential Tools & Materials)

| Item | Function & Specification |

|---|---|

| NVIDIA GPU | Compute platform. For modern research, an architecture of Compute Capability 7.0 (Volta) or higher is recommended for advanced profiling metrics. |

| CUDA Toolkit [17] | Software development environment. Version 11.0 or newer is required for Nsight Compute and updated profiling features. |

| NVIDIA Nsight Systems [20] | System-wide performance analysis tool. Used for initial bottleneck identification (e.g., excessive kernel launch overhead or data transfer times). |

| NVIDIA Nsight Compute [43] [20] | Detailed kernel profiler. Used for fine-grained analysis of memory transactions, warp efficiency, and occupancy. |

2. Methodology

Step 1: Establish a Baseline with a Naive Kernel

Begin with a simple, often inefficient, kernel implementation to establish a performance baseline. For matrix multiplication, this would be a kernel where each thread computes one element of the output matrix C by iterating over a row of A and a column of B [14].

- Profiling: Use Nsight Compute to profile this kernel. Note key metrics like execution duration and memory transaction efficiency (

l1tex__average_t_sectors_per_request_pipe_lsu_mem_global_op_ld.ratio). The access toB[i * N + col]is strided because consecutive threads (with consecutivecolvalues) access elements separated byNelements, preventing coalescing [14].

Step 2: Apply Shared Memory Tiling for Coalesced Access

Optimize the kernel by using shared memory to cache tiles of data from A and B. This transforms strided global memory accesses into coalesced ones [43] [14].

- Coalesced Data Loading: Each thread block collaboratively loads a tile of

Aand a tile ofBfrom global memory into shared memory. The loading pattern is arranged so that threads within a warp access contiguous global memory addresses. - Data Reuse and Computation: The thread block then performs its computation by reading from the fast, on-chip shared memory. This allows the strided access to

Bto happen from shared memory, where it is much less expensive. - Profiling and Validation: Profile the optimized kernel with Nsight Compute. You should observe a significant increase in memory transaction efficiency (ratio closer to 4) and a reduction in the total number of memory sectors transferred [43] [20]. Always validate that the output of the optimized kernel matches the naive kernel to ensure correctness.

Step 3: Advanced Optimization - Vectorized Memory Access

For further optimization on supported architectures, use vectorized loads (e.g., float2, float4) to increase the bytes transferred per memory transaction [14].

- Implementation: Modify the shared memory loading code to have each thread load multiple contiguous elements via a vector type. This increases the arithmetic intensity of the kernel and can help achieve higher memory bandwidth utilization.

- Profiling: The final profiling step should show a further reduction in instruction count and an increase in achieved GFLOPs, moving performance closer to the hardware's peak [14].

The iterative optimization process from a naive kernel to one using shared memory tiling and vectorization can lead to performance improvements of over 60x compared to the initial, naive implementation [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Profiling Commands for Memory Analysis

Use the following commands with NVIDIA's tools to diagnose and analyze memory coalescing in your kernels.

| Tool | Command / Metric | Purpose & Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Nsight Compute(Kernel-level) [43] [20] | ncu --metrics l1tex__t_sectors_pipe_lsu_mem_global_op_ld.sum,l1tex__t_sectors_pipe_lsu_mem_global_op_st.sum ./app |

Counts total global memory transactions. Lower is better. |

ncu --metrics l1tex__average_t_sectors_per_request_pipe_lsu_mem_global_op_ld.ratio ./app |

Measures efficiency of each transaction. A value of 4 is optimal. | |

| Nsight Systems(System-level) [20] | nsys profile -o test_report ./your_application |

Generates a timeline to identify if slow kernels or data transfers are the primary bottleneck. |

| Compute Sanitizer(Debugging) [20] | compute-sanitizer --tool memcheck ./app |

Checks for out-of-bounds memory accesses that can ruin coalescing. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Resolving Performance Regressions After Kernel Fusion

Q: I fused several operators into a single kernel, but my overall performance is now worse. What could be causing this?

A performance regression after fusion often results from exceeding on-chip resource limits, which reduces GPU occupancy. This guide will help you diagnose and fix the most common issues.

- Symptom: Slower execution times after fusing kernels.

- Investigation Tools: Use

nvidia-smito monitor real-time GPU utilization and profilers like Nsight Systems or Nsight Compute for detailed analysis [46].

| Problem | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High Register Pressure | Profile with Nsight Compute; check for register spilling to local memory [47]. | Restructure code to reduce per-thread register usage; use compiler flags to limit register count (e.g., -maxrregcount). |

| Shared Memory Exhaustion | Check profiler for shared memory usage per block and occupancy limits [47] [48]. | Reduce the shared memory footprint of your kernel; rework data tiles or buffers. |

| Low Occupancy | Use profiler to measure active warps per Streaming Multiprocessor (SM); low numbers indicate occupancy issues [47]. | Reduce resource usage (registers, shared memory) per thread block to allow more concurrent blocks on an SM. |

| Thread Block Misalignment | Verify that the fused kernel's thread block structure is optimal for all combined operations [47]. | Re-design the work partitioning in the fused kernel to ensure efficient mapping to GPU resources. |

Guide 2: Debugging Functional Errors in Fused Kernels

Q: My fused kernel runs without crashing, but it produces incorrect results. How can I systematically debug it?

Functional errors in fused kernels are often due to incorrect synchronization or memory access pattern changes.

- Symptom: The fused kernel produces different results from the sequence of original, unfused kernels.

- Investigation Tools: Use

printfinside the kernel and CUDA-GDB for step-by-step debugging [49].

| Problem | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Missing Synchronization | Check if later stages of the kernel use data produced by earlier stages before writes are complete [47]. | Insert __syncthreads() where necessary to ensure data produced by one thread block stage is visible to others. |

| Incorrect Memory Access | Use CUDA-MEMCHECK to identify out-of-bounds accesses. Add printf to log thread indices and memory addresses [49]. |

Carefully review the indexing logic for all memory operations in the fused kernel. |

| Violated Data Dependencies | Manually trace the flow of a single data element through the entire fused kernel logic. | Ensure the execution order of fused operations respects all producer-consumer relationships. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between kernel fusion and other model optimization techniques like quantization?

Kernel fusion is an exact optimization that merges the code of multiple operations without altering the underlying mathematical result or approximating calculations. It primarily targets efficiency by minimizing data transfer overhead [50]. In contrast, techniques like quantization are approximate optimizations that reduce computational precision to shrink model size and speed up execution, potentially at the cost of minor accuracy loss [51].

Q2: My model uses a standard Transformer architecture. Which fusion opportunities should I prioritize?

For Transformer models, the most impactful fusion patterns to implement or look for in compilers are [50] [48] [52]:

- QKV Projection + Attention + O Projection: Fusing the entire attention mechanism.

- Matrix Multiplication + Add Bias + Activation (e.g., GELU, SiLU): Common in feed-forward networks.

- Layer Normalization or RMS Normalization with subsequent operations.

- Residual Connection Add with a following activation.

Q3: Are there situations where fusing kernels is not recommended?

Yes, kernel fusion is not always beneficial. Avoid it in these scenarios [47] [50] [49]:

- When the fused kernel becomes so large and complex that it causes register spilling or significantly lowers GPU occupancy.

- When trying to fuse independent operations that could run in parallel; fusion might serialize them and reduce parallelism.

- For very simple or single-step computations where the fusion overhead outweighs the benefits.

- When debuggability and code maintainability are a higher priority than peak performance.

Q4: How do modern deep learning frameworks like PyTorch and TensorFlow apply kernel fusion automatically?

Frameworks use graph compilers that apply fusion as a graph transformation pass [53]:

- PyTorch uses

torch.jitscripts, thetorch.quantization.fuse_modulesfunction, and the newer TorchInductor compiler in PyTorch 2.0 to identify and fuse common patterns likeConv2d + BatchNorm2d + ReLU[53]. - TensorFlow uses its Grappler graph optimizer and the XLA (Accelerated Linear Algebra) compiler to fuse operations, which is especially effective when a function is decorated with

@tf.function(jit_compile=True)[53]. - ONNX Runtime applies a series of graph transformer passes (e.g.,

GemmActivationFusion,LayerNormFusion) on the model graph to merge nodes before execution [53].

Q5: What is "kernel fission" and when would I use it?

Kernel fission is the opposite of fusion; it involves splitting a single, complex kernel into two or more simpler kernels. This is considered when a monolithic kernel performs suboptimally. The goal is to create smaller kernels that can be:

- More efficiently vectorized.

- More effectively scheduled by the GPU's hardware [50]. This strategy is less common than fusion but can be useful for optimizing very large, heterogeneous kernels.

Experimental Protocols & Performance Data

Protocol: Vertical Fusion for a Transformer's Feed-Forward Network

This protocol details the steps to manually fuse a sequence of operations in a Transformer's MLP block.

1. Identify the Target Operation Chain

Locate the sequence: Matrix Multiplication (MatMul) -> Add Bias -> GELU Activation -> Matrix Multiplication (MatMul) [50] [52].

2. Analyze Data Dependencies and Intermediate Results

- The first

MatMulproduces an output matrix. - The

Add BiasandGELUoperations are performed element-wise on this matrix. - The second

MatMuluses the result ofGELU. - The intermediate results between these steps are written to and read from global memory in the unfused version.

3. Fuse Element-Wise Operations

Merge the MatMul, Add Bias, and GELU into a single kernel. The key is to perform the element-wise operations immediately after calculating each element (or tile) of the first MatMul's output, keeping the intermediate values in fast on-chip registers or shared memory [52].

4. Implement the Fused Kernel Write a kernel where each thread or thread block:

- Loads input tiles and weight matrices from global memory.

- Computes a portion of the first

MatMul. - Immediately adds the bias and applies the GELU activation to that portion.

- Uses the result for its portion of the second

MatMul(if feasible) or writes the final GELU output for the second fused kernel. - Writes only the final output back to global memory.

Quantitative Performance Data

The table below summarizes published speedups from applying kernel fusion across different applications.

| Application / Fused Pattern | Hardware | Speed-up Over Unfused Baseline | Key Fused Operations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atomistic Spin Dynamics [47] | NVIDIA A100 | 26-33% | GEMM + Element-wise Epilogue |

| Deep Learning Operator Graphs (DNNFusion) [47] | Embedded/Mobile GPUs | Up to 9.3x | Various ONNX Graph Operators |

| Hyperbolic Diffusion (3D Flow) [47] | GPU | ~4x | Flux Computation + Divergence + Source |

| Llama-70B Inference (Megakernel) [48] | NVIDIA H100 | >22% end-to-end throughput | Full model forward pass (overlapped compute/memory/communication) |

| BLAS-1 / BLAS-2 Sequences [47] | GPU | Up to 2.61x | AXPY + DOT, SGEMV/GEMVT pairs |

Workflow and Signaling Diagrams

Kernel Fusion Workflow

Memory Access Pattern

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Tool / Framework | Function | Use Case Example |

|---|---|---|

| NVIDIA Nsight Compute & Nsight Systems [46] | Profiling and debugging tools for detailed performance analysis of CUDA kernels. | Identifying performance bottlenecks, register pressure, and shared memory usage in a custom fused kernel [47]. |

| CUTLASS [47] | CUDA C++ template library for implementing high-performance GEMM and related operations. | Creating custom, fused GEMM epilogues that integrate operations like bias addition and activation [47]. |

| OpenAI Triton [54] | Open-source Python-like language and compiler for writing efficient GPU code. | Prototyping and implementing complex fused kernels without writing low-level CUDA code. |

| PyTorch FX / TorchInductor [53] | PyTorch's graph transformation and compilation stack. | Automatically fusing a sequence of operations in a PyTorch model for accelerated inference. |

| ONNX Runtime [53] | High-performance inference engine for ONNX models. | Applying graph-level fusion passes (e.g., GemmActivationFusion) to an exported model for optimized deployment. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Resolving Lack of Kernel Concurrency in Multiple Streams

Problem: Kernels launched in different CUDA streams are executing sequentially rather than in parallel, reducing overall throughput.

Diagnosis:

- Check if individual kernels are large enough to fully utilize all GPU execution resources. A kernel that fully occupies the GPU will prevent concurrent execution of other kernels [55].

- Verify kernel launch configuration. Very small block sizes (e.g., 32 threads) may be suboptimal and affect how workloads are distributed [55].

- Confirm the GPU platform and driver. Windows WDDM drivers may introduce performance artifacts due to launch batching [55].

Solution: