Optimizing Accelerometer Sampling Rates: A Practical Guide for Accurate Behavior Classification in Biomedical Research

This article systematically compares the effects of accelerometer sampling frequency on the accuracy of machine learning-based behavior classification, drawing on recent research from both human and animal studies.

Optimizing Accelerometer Sampling Rates: A Practical Guide for Accurate Behavior Classification in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article systematically compares the effects of accelerometer sampling frequency on the accuracy of machine learning-based behavior classification, drawing on recent research from both human and animal studies. It explores the foundational trade-offs between data resolution and device resources, provides methodological guidance for selecting appropriate sampling rates for different behavioral phenotypes, and offers optimization strategies for long-term monitoring in clinical and preclinical settings. By synthesizing evidence across species and research domains, this review delivers actionable insights for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to implement accelerometry for robust digital biomarker development, with a focus on balancing analytical precision with practical constraints in battery life, data storage, and computational requirements.

The Sampling Frequency Dilemma: Balancing Data Integrity and Practical Constraints

The Nyquist-Shannon Theorem and its Critical Role in Accelerometer Data Collection

The Nyquist-Shannon Theorem establishes a fundamental principle for digital signal processing, stating that to perfectly reconstruct a continuous signal from its samples, the sampling frequency must be at least twice the highest frequency contained in the signal [1]. This theorem serves as a critical guideline in accelerometer data collection for behavior classification, ensuring that the recorded digital data accurately represents the original analog movement signals. When researchers select sampling rates below this Nyquist criterion, they risk aliasing—a form of distortion where high-frequency components disguise themselves as lower frequencies, potentially compromising the integrity of the collected data and subsequent behavioral classification accuracy [1].

In practical research settings, accelerometer sampling frequency directly influences multiple aspects of study design: it determines the minimum detectable movement dynamics, affects device battery life and storage requirements, and ultimately governs the classification accuracy of machine learning algorithms for identifying specific behaviors. This guide examines how the Nyquist-Shannon Theorem informs sampling rate selection across diverse research contexts, from human activity recognition to animal behavior studies, and provides experimental data comparing classification performance across different sampling frequencies.

Empirical Evidence: Sampling Frequency Effects on Classification Accuracy

Research across multiple domains demonstrates that sampling frequency requirements vary significantly depending on the specific behaviors being classified. The following table summarizes key findings from recent studies:

| Research Context | Optimal Sampling Frequency | Behaviors Classified | Classification Performance | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human Activity Recognition | 10 Hz | Lying, walking, running, brushing teeth | Maintained accuracy comparable to 100 Hz; significant drop at 1 Hz [2] | PMC (2025) |

| Lemon Shark Behavior | 5 Hz for most behaviors; >5 Hz for fine-scale | Swim, rest, burst, chafe, headshake | Swim/rest: F-score >0.964 at 5 Hz; Fine-scale: Significant drop <5 Hz [3] | Journal of Experimental Biology (2018) |

| Animal Behavior (Dingo) | 1 Hz | 14 different behaviors | Mean accuracy of 87% with random forest classifier [4] | Journal of Experimental Biology (2018) |

| General HAR Benchmark | 12-63 Hz | Various daily activities | "Sufficient" for classification accuracy [5] | Pattern Recognition Letters (2016) |

| Wild Red Deer Behavior | 4 Hz (averaged over 5-min) | Lying, feeding, standing, walking, running | Accurate classification with discriminant analysis [6] | Animal Biotelemetry (2025) |

These findings reveal that while the Nyquist-Shannon Theorem provides a theoretical foundation, practical sampling frequency selection involves balancing classification accuracy with operational constraints. For slow-moving behaviors (resting, lying, slow walking), sampling frequencies as low as 1-5 Hz often suffice for accurate classification. In contrast, fast-kinematic behaviors (headshakes, tooth brushing, bursts of speed) typically require higher sampling rates (5-10 Hz or more) to capture movement details necessary for reliable classification [2] [3].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Human Activity Recognition Protocol

A 2025 study examining sampling frequency effects on human activity recognition enrolled 30 healthy participants who wore nine-axis accelerometer sensors at five body locations while performing nine specific activities [2]. Researchers collected data at 100 Hz using ActiGraph GT9X Link devices, then down-sampled to 50, 25, 20, 10, and 1 Hz for analysis. Machine learning-based activity recognition was performed separately for each sampling frequency, with accuracy comparisons focusing on non-dominant wrist and chest placements, which previously demonstrated high recognition accuracy. This methodology enabled direct comparison of how reduced sampling frequencies affect classification performance for clinically relevant activities [2].

Animal Behavior Classification Framework

Research on juvenile lemon sharks exemplifies a systematic approach to evaluating sampling frequency effects [3]. Scientists conducted semi-captive trials with dorsally-mounted triaxial accelerometers recording at 30 Hz simultaneously with direct behavioral observations. This ground-truthing process created a labeled dataset correlating specific acceleration patterns with five distinct behaviors: swim, rest, burst, chafe, and headshake. The raw data was then resampled to 15, 10, 5, 3, and 1 Hz, with a random forest machine learning algorithm trained and tested at each frequency. Performance was evaluated using F-scores, which combine precision and recall metrics, providing a comprehensive view of how sampling frequency affects classification of both common and fine-scale behaviors [3].

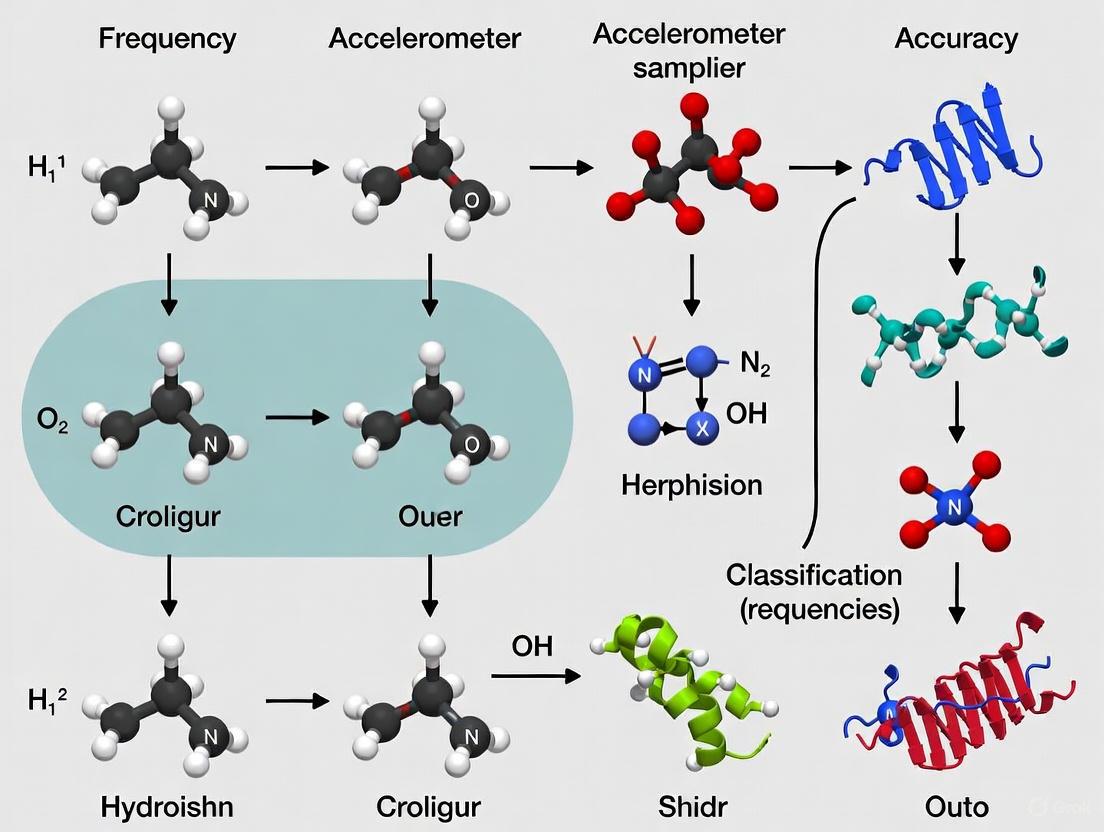

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for evaluating sampling frequency effects on behavior classification accuracy.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Materials

Successful accelerometer-based behavior classification requires careful selection of both hardware and analytical components. The following table outlines essential research reagents and solutions:

| Research Component | Specification Examples | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Triaxial Accelerometers | ActiGraph GT9X Link, Cefas G6a+, VECTRONIC Aerospace collars [2] [3] [6] | Measures acceleration in three dimensions (x, y, z axes) to capture movement intensity and direction |

| Data Acquisition Platforms | ActiLife software, Custom firmware [7] [6] | Configures sampling parameters, stores raw data, and enables data retrieval |

| Machine Learning Algorithms | Random Forest, Support Vector Machines, Discriminant Analysis, k-Nearest Neighbors [2] [4] [6] | Classifies behaviors from acceleration patterns using trained models |

| Validation Metrics | F-scores, Accuracy, Precision, Recall [3] [6] | Quantifies classification performance and enables model comparison |

| Data Processing Tools | Python, R, MATLAB [5] [6] | Downsampling, feature extraction, and statistical analysis |

The selection of appropriate sampling frequency represents a critical trade-off between data integrity and practical constraints. Higher sampling rates (30-100 Hz) potentially capture more movement detail but significantly reduce deployment duration due to increased power consumption and memory usage [5] [3]. Lower sampling rates (1-10 Hz) extend monitoring periods but risk missing fine-scale behaviors and violating the Nyquist criterion, potentially introducing aliasing artifacts [1] [3].

Figure 2: Trade-offs between high and low sampling frequencies in accelerometer-based behavior research.

The Nyquist-Shannon Theorem provides the theoretical foundation for selecting appropriate accelerometer sampling frequencies, but practical implementation requires balancing this principle with research-specific objectives and constraints. For behavior classification, researchers must consider the kinematic properties of target behaviors, with fast movements requiring higher sampling rates (≥5-10 Hz) than slower, more rhythmic activities (1-5 Hz) [2] [3].

Empirical evidence across species indicates that optimal sampling frequencies are highly behavior-dependent, with 5-10 Hz representing a practical compromise for many classification tasks. This frequency range typically satisfies the Nyquist criterion for most gross motor activities while maintaining feasible power and storage requirements for extended monitoring. Researchers should conduct pilot studies with their specific subject population and behaviors of interest to determine the minimal sufficient sampling frequency, thereby optimizing resource utilization without compromising classification accuracy [5].

In behavior classification research using accelerometers, one of the most critical decisions involves selecting an appropriate sampling frequency. This parameter sits at the center of a fundamental trade-off: higher data resolution against the practical constraints of battery life, storage capacity, and computational load. Higher sampling rates can capture more nuanced movement dynamics, potentially improving the classification of fine-scale behaviors. However, this comes at a steep cost to system resources, which can limit deployment duration, increase data handling burdens, and constrain device miniaturization. This guide objectively compares these trade-offs, synthesizing recent experimental data to inform researchers and drug development professionals in optimizing their study designs for both scientific rigor and operational feasibility.

Quantifying the Impact of Sampling Frequency

The relationship between sampling frequency and resource consumption is direct, but its impact on classification accuracy is nuanced and depends on the specific behaviors of interest. The following table summarizes key experimental findings on how reducing sampling frequency affects behavior classification performance.

Table 1: Impact of Sampling Frequency on Behavior Classification Accuracy

| Study Context | Sampling Frequencies Tested | Key Findings on Classification Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Human Activity Recognition (Healthy Adults) [2] | 100, 50, 25, 20, 10, 1 Hz | Reducing the frequency to 10 Hz did not significantly affect recognition accuracy for non-dominant wrist and chest sensors. Accuracy decreased for many activities at 1 Hz, particularly for brushing teeth. |

| Animal Behavior (Lemon Sharks) [3] | 30, 15, 10, 5, 3, 1 Hz | 5 Hz was suitable for classifying "swim" and "rest" (F-score > 0.96). Classification of fine-scale behaviors (headshake, burst) required >5 Hz for best performance. |

| Infant Movement Analysis [8] | 52, 40, 25, 13, 6 Hz | The sampling frequency could be reduced from 52 Hz to 6 Hz with negligible effects on the classification of postures and movements. A minimum of 13 Hz was recommended. |

| Human Locomotor Tasks [9] | Ranged from 20-100 Hz in literature; 40 Hz found optimal | A sampling rate of 40 Hz provided optimal discrimination for locomotor tasks. The study highlighted that lower frequencies risk missing information, while higher frequencies risk overfitting. |

Conversely, lowering the sampling frequency has a direct and positive impact on resource conservation. The table below outlines the theoretical benefits, which are consistently observed across studies.

Table 2: Resource Trade-offs of Lower Sampling Frequencies

| Resource | Impact of Lower Sampling Frequency | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Battery Life | Increases significantly due to reduced power consumption per unit time. | Enables long-term monitoring and device miniaturization for clinical applications [2]. |

| Storage Capacity | Increases effectively, allowing for longer deployment durations. | Maximizes available device memory, extending insight to ecologically relevant time scales [3]. |

| Computational Load | Reduces data processing time and required memory. | Decreases computational burden, which is critical for resource-constrained applications [9]. |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

To ensure the validity and comparability of findings on sampling frequency, researchers adhere to structured experimental protocols. The following workflow visualizes a standard methodology for determining the optimal sampling frequency for behavior classification.

Determining Optimal Sampling Frequency

Detailed Experimental Methodology

The process for assessing sampling frequency effects is systematic and can be broken down into several key stages, as detailed in the cited literature:

High-Frequency Data Collection & Ground-Truthing: Experiments begin by collecting raw accelerometer data at a high sampling frequency (e.g., 52-100 Hz) sufficient to capture all potential movements of interest [9] [3] [8]. This data is synchronously ground-truthed through direct observation (e.g., video recordings in infants [8] or semi-captive trials in animal studies [3]), where expert annotators label the data with specific behaviors (e.g., rest, swim, walk slow, walk fast).

Systematic Downsampling and Feature Extraction: The original high-frequency dataset is then systematically downsampled to a range of lower frequencies (e.g., 40 Hz, 10 Hz, 5 Hz, 1 Hz) for comparative analysis [2] [3]. At each frequency, the time-series data is segmented into windows, and features (such as mean, standard deviation, spectral features from Fast Fourier Transform) are extracted from these windows to characterize the signal [9] [10].

Model Training and Performance Evaluation: Machine learning models (e.g., Random Forests, Support Vector Machines) are trained on the feature sets from each sampling frequency to classify the ground-truthed behaviors [3] [10]. Classifier performance is rigorously evaluated using metrics like F-score (which combines precision and recall) or Cohen's Kappa [3] [8]. The optimal sampling frequency is identified as the lowest rate that maintains a statistically insignificant drop in performance compared to the highest rate, thereby preserving classification accuracy while maximizing resource efficiency [2] [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Selecting the right equipment and methodologies is fundamental to conducting valid and reproducible research in this field. The following table details key materials and their functions.

Table 3: Essential Research Materials and Tools for Accelerometer-Based Behavior Classification

| Tool / Material | Function in Research | Example Context |

|---|---|---|

| Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) | The core sensor, typically containing a triaxial accelerometer and often a gyroscope, to measure movement and orientation. | Wearable sensors (Axivity AX6) on sacrum, thighs, and shanks for locomotor task discrimination [9]. |

| Multi-Sensor Wearable Suit | A garment with integrated IMUs at key body locations (e.g., proximal limbs) to capture comprehensive movement data. | The MAIJU jumpsuit for naturalistic measurement of infant postures and movements [8]. |

| Annotation & Data Logging Software | Custom software to synchronize sensor data with video recordings, enabling manual ground-truth labeling by human experts. | Software used for synchronizing video and IMU data for infant [8] and animal behavior studies [3]. |

| Supervised Machine Learning Pipeline | The analytical framework that uses ground-truthed data to train algorithms for automatic behavior classification from new data. | Random Forest algorithm for classifying shark behaviors (swim, rest, burst) [3]; Deep learning pipelines for infant movement classification [8]. |

The quest for optimal accelerometer sampling frequency is not about maximizing data resolution at all costs, but about finding the sweet spot that satisfies the requirements of classification accuracy while operating within the practical limits of battery, storage, and computation. Experimental evidence consistently shows that for a broad range of behaviors—from human locomotor tasks and daily activities to animal movements—sampling frequencies between 5 Hz and 40 Hz are often sufficient, with specific choices depending on the kinematics of the target behaviors. By adopting a methodical approach to sampling frequency selection, as outlined in this guide, researchers can design more efficient, longer-lasting, and scalable studies without compromising the integrity of their scientific conclusions.

The accurate classification of behavior—from sustained postures to fleeting, high-velocity motions—represents a critical challenge in movement science, pharmacology, and drug development. As researchers increasingly rely on accelerometer-derived digital biomarkers to quantify behavioral outcomes in clinical trials, understanding the fundamental relationship between sensor sampling frequencies and classification accuracy becomes paramount. The selection of an appropriate sampling rate must balance competing demands: capturing sufficient kinematic detail to distinguish behaviorally distinct movements while minimizing data volume, power consumption, and processing requirements for long-term monitoring.

Recent advances in wearable technology have enabled unprecedented resolution in movement tracking, yet consensus remains elusive regarding optimal sampling strategies for comprehensive behavioral assessment. This guide systematically compares the performance of different sampling frequency configurations across diverse experimental paradigms, from human activity recognition to wildlife tracking. By synthesizing empirical evidence from current literature, we provide a evidence-based framework for selecting sampling parameters that maximize classification accuracy while maintaining practical feasibility for large-scale and long-duration studies.

Theoretical Foundation: Movement Dynamics and the Nyquist Principle

The theoretical basis for sampling frequency selection originates from the Nyquist-Shannon sampling theorem, which states that a signal must be sampled at least twice as fast as its highest frequency component to avoid aliasing and ensure faithful reconstruction. However, the application of this principle to behavior classification is complicated by the multi-dimensional nature of movement, where amplitude, frequency, and temporal characteristics vary significantly across behavioral categories.

Static postures (sitting, standing, lying) produce primarily low-frequency gravitational components typically below 0.25 Hz, whereas transitional movements (sit-to-stand, posture changes) generate higher-frequency bodily acceleration components up to 3-5 Hz. Locomotor activities exhibit distinct spectral signatures, with walking producing fundamental frequencies between 1-2 Hz and running generating components up to 4-5 Hz. The most challenging behaviors to capture are brief, transient motions (fidgeting, startle responses, fine motor adjustments) that may contain frequency components exceeding 10 Hz but occur in timeframes of milliseconds to seconds.

Table: Frequency Characteristics of Different Behavioral Classes

| Behavioral Class | Dominant Frequency Range | Key Kinematic Features | Representative Behaviors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Static Postures | 0-0.25 Hz | Gravitational orientation | Sitting, standing, lying down |

| Dynamic Transitions | 0.5-3 Hz | Whole-body acceleration | Sit-to-stand, posture shifts |

| Cyclic Locomotion | 1-5 Hz | Rhythmic, periodic patterns | Walking, running, climbing |

| Transient Motions | 5-20+ Hz | Brief, high-acceleration | Fidgeting, corrective adjustments, startle responses |

Comparative Analysis of Sampling Frequency Performance

Human Activity Recognition: From Ambulatory Activities to Daily Living

A 2025 systematic investigation examined sampling frequency requirements for recognizing clinically relevant activities in healthy adults using nine-axis accelerometers positioned at multiple body locations. Participants performed nine activities representing a continuum of movement velocities, with data collected at 100 Hz and subsequently downsampled to compare classification accuracy across frequencies [2].

Table: Sampling Frequency Effects on Human Activity Recognition Accuracy [2]

| Sampling Frequency | Non-Dominant Wrist Accuracy | Chest Accuracy | Data Volume Reduction | Activities Most Affected |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 Hz | 95.2% (reference) | 96.1% (reference) | 0% | None (reference) |

| 50 Hz | 95.1% | 96.0% | 50% | None |

| 25 Hz | 95.0% | 95.9% | 75% | None |

| 20 Hz | 94.9% | 95.8% | 80% | None |

| 10 Hz | 94.7% | 95.6% | 90% | None |

| 1 Hz | 82.3% | 85.1% | 99% | Tooth brushing, transitional movements |

The research demonstrated that sampling frequencies could be reduced to 10 Hz without significant degradation in recognition accuracy for both wrist and chest placements. However, reducing to 1 Hz substantially compromised performance, particularly for behaviors with important high-frequency components such as tooth brushing (characterized by rapid, oscillatory hand motions). These findings indicate that for most ambulatory activities and basic postures, a 10 Hz sampling rate provides sufficient temporal resolution while reducing data volume by 90% compared to standard 100 Hz collection [2].

Animal Behavior Classification: From Sedentary to High-Velocity Movements

Research in wildlife tracking provides valuable insights into sampling requirements across a diverse spectrum of naturally occurring behaviors. A comprehensive 2019 study on seabird behavior classification compared six different methods for identifying behaviors ranging from stationary postures to flight using tri-axial accelerometers [11].

The study found that high accuracy (>98% for thick-billed murres; 89-93% for black-legged kittiwakes) could be maintained across multiple behavioral categories including standing, swimming, and flying using relatively simple classification methods with 2-3 key predictor variables. Interestingly, complex machine learning approaches did not substantially outperform simpler threshold-based methods when the goal was creating daily activity budgets rather than identifying subtle behavioral nuances [11].

Complementary research in wild red deer (2025) further demonstrated that low-resolution acceleration data (averaged over 5-minute intervals) could successfully differentiate between lying, feeding, standing, walking, and running behaviors when appropriate classification algorithms were applied. The study compared multiple machine learning approaches and found that discriminant analysis with min-max normalized acceleration data generated the most accurate classification models for these coarse behavioral categories [6].

Sensor Configuration and Placement Interactions with Sampling Frequency

The optimal sampling frequency is influenced by sensor placement, as body location affects the amplitude and frequency characteristics of recorded movements. Research comparing single-sensor configurations found that the thigh was the optimal placement for identifying both movement and static postures when using only one accelerometer, achieving a misclassification error of 10% [12].

For two-sensor configurations, the waist-thigh combination identified movement and static postures with greater accuracy (11% misclassification error) than thigh-ankle sensors (17% error). However, the thigh-ankle configuration demonstrated superior performance for classifying walking/fidgeting and jogging, with sensitivities and positive predictive values greater than 93% [12].

A systematic assessment of IMU-based movement recordings emphasized that single-sensor configurations have limited utility for assessing complex real-world movement behavior, recommending instead a minimum configuration of one upper and one lower extremity sensor. This research further indicated that sampling frequency could be reduced from 52 Hz to 13 Hz with negligible effects on classification performance for most activities, and that accelerometer-only configurations (excluding gyroscopes) led to only modest reductions in movement classification performance [13].

Diagram 1: Decision Framework for Accelerometer Configuration Based on Behavioral Targets

Methodological Considerations for Experimental Protocols

Standardized Experimental Protocols for Sampling Frequency Validation

Research evaluating sampling frequency effects on human activity recognition employed comprehensive protocols in which 30 healthy participants performed nine activities while wearing five synchronized accelerometers. The activities were strategically selected to represent a spectrum of movement velocities and patterns: lying in supine and lateral positions, sitting, standing, walking, running, ascending/descending stairs, and tooth brushing. Sensors were configured to sample at 100 Hz with idle sleep mode disabled, and data were subsequently downsampled to compare performance across frequencies from 1-100 Hz. This approach enabled direct comparison of classification accuracy while controlling for inter-session variability [2].

In animal behavior studies, researchers have developed alternative validation methodologies when direct observation is impossible. The seabird behavior study utilized GPS tracking data as a validation reference for accelerometer-based classifications, comparing behavioral inferences from high-resolution location data (capable of identifying sitting, flying, and swimming) with concurrently collected accelerometer data. This approach provided ground-truth validation for free-living animals engaged in natural behaviors across their full ecological range [11].

Signal Processing and Feature Extraction Techniques

The transformation of raw accelerometer data into classifiable features requires multiple processing stages. Research on human posture and movement classification implemented a comprehensive pipeline beginning with calibration and median filtering (window size of three) to remove high-frequency noise spikes. The filtered signal was then separated into gravitational and bodily motion components using a third-order zero phase lag elliptical low-pass filter with a cut-off frequency of 0.25 Hz [12].

For movement detection, both signal magnitude area (SMA) thresholds and continuous wavelet transforms (CWT) have been employed. SMA thresholds effectively identify moderate-to-vigorous movements but may miss lower-frequency activities like slow walking. To address this limitation, CWT using a Daubechies 4 Mother Wavelet applied over the 0.1-2.0 Hz frequency range can detect rhythmic, low-intensity movements that fall below SMA thresholds [12].

In animal studies, researchers have successfully employed multiple accelerometer metrics including depth (for diving species), wing beat frequency, pitch, and dynamic acceleration. Variable selection analyses have demonstrated that classification accuracy frequently does not improve with more than 2-3 carefully selected variables, suggesting that feature quality is more important than quantity for basic behavior classification [11].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Methodological Components

Table: Essential Methodological Components for Movement Behavior Research

| Component Category | Specific Solutions | Function & Application | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensor Platforms | Tri-axial accelerometers | Capture multi-dimensional movement data | ActiGraph GT9X [2], Custom-built Mayo Clinic monitors [12] |

| Biotelemetry Systems | GPS-accelerometer collars | Wildlife behavior tracking in natural habitats | VECTRONIC Aerospace collars [6], Axy-trek [11] |

| Signal Processing Tools | Digital filters | Separate gravitational and motion components | Elliptical low-pass filter (0.25 Hz) [12], Median filters [12] |

| Classification Algorithms | Machine learning libraries | Behavior classification from movement features | Random Forest, Discriminant Analysis [6], SVM [2] |

| Validation Methodologies | GPS tracking, video recording | Ground-truth behavior annotation | Synchronized video validation [12], GPS path analysis [11] |

Implications for Research and Drug Development

The systematic evaluation of sampling frequency effects on behavior classification accuracy has profound implications for pharmaceutical research and clinical trial design. First, the finding that many clinically relevant behaviors can be accurately captured at sampling frequencies of 10-25 Hz enables the development of more efficient monitoring devices with extended battery life, supporting longer observation periods without compromising data quality [2]. This is particularly valuable for chronic conditions requiring continuous monitoring over weeks or months.

Second, the demonstrated viability of simpler classification approaches (threshold-based methods, linear discriminant analysis) for distinguishing basic behavioral categories suggests that complex deep learning models may be unnecessary for many clinical applications focused on gross motor activity, potentially increasing transparency and reducing computational barriers for regulatory review [11] [6].

Third, the optimized sensor configurations identified through comparative studies enable researchers to balance patient burden against data completeness. The recognition that single thigh-mounted sensors can accurately classify both static postures and dynamic movements (10% misclassification error) provides a less intrusive alternative to multi-sensor setups, potentially improving compliance in vulnerable populations [12].

Diagram 2: Signal Processing and Classification Workflow for Multi-Scale Movement Analysis

The evidence synthesized in this comparison guide demonstrates that behavior-specific movement frequencies dictate distinct sampling requirements across the spectrum of motor activities. For researchers targeting gross motor patterns including basic postures, transitions, and ambulatory activities, sampling frequencies of 10-25 Hz provide sufficient temporal resolution while optimizing data efficiency. In contrast, investigations focusing on brief, transient motions or fine motor control necessitate higher sampling rates (50-100 Hz) to capture relevant kinematic details.

Sensor configuration similarly requires strategic alignment with research objectives. Single sensor implementations (particularly thigh placement) provide viable solutions for classifying basic activity budgets, while dual-sensor configurations (combining upper and lower extremity placements) enable more nuanced discrimination of complex behavioral repertoires. Classification algorithm selection should be guided by both behavioral complexity and interpretability requirements, with simpler threshold-based methods often sufficing for gross motor classification while complex machine learning approaches remain necessary for fine-grained behavioral phenotyping.

These methodological considerations form a critical foundation for advancing movement science in pharmaceutical research, enabling the development of valid, reliable, and efficient digital biomarkers for clinical trials across diverse therapeutic areas including neurology, psychiatry, and gerontology.

The Implications of Aliasing and Signal Distortion When Sampling Below Nyquist Frequency

The Nyquist-Shannon sampling theorem establishes a fundamental principle for digital signal acquisition: to accurately represent a continuous signal without loss of information, the sampling frequency must be at least twice the highest frequency component present in the signal being measured [14]. This critical threshold is known as the Nyquist frequency. When researchers sample accelerometer data below this frequency, they risk aliasing, a phenomenon where high-frequency signals are misrepresented as lower-frequency artifacts in the sampled data [15]. In the context of behavior classification research, aliasing can distort critical movement signatures, compromise classification accuracy, and ultimately lead to flawed scientific conclusions.

For researchers investigating animal behavior or human physical activity, aliasing presents a particularly insidious problem. The signal distortion introduced by undersampling can create the appearance of movement patterns that don't actually exist, while simultaneously obscuring genuine behavioral signatures [16] [14]. This guide systematically compares the effects of different sampling strategies on data quality and analytical outcomes, providing evidence-based recommendations for selecting appropriate sampling frequencies across various research scenarios.

Theoretical Foundations of Aliasing in Sensor Systems

The Nyquist-Shannon Theorem

The Nyquist-Shannon theorem provides the mathematical foundation for modern digital signal processing. According to this theorem, perfect reconstruction of a signal from its samples is possible only if the uniform sampling frequency (fs) exceeds twice the maximum frequency (fmax) present in the signal: fs > 2 × fmax [15]. The frequency 2 × f_max is called the Nyquist rate. Sampling below this rate violates the theorem's basic assumption, making accurate signal reconstruction impossible.

When this assumption is violated, aliasing occurs because the sampling process cannot distinguish between frequency components separated by integer multiples of the sampling rate. In MEMS accelerometers, this manifests as high-frequency vibrations appearing as lower-frequency oscillations in the sampled data [14]. For example, in vibration sensing applications for condition-based monitoring, aliasing can lead to catastrophic failures because the aliased signal may not be present in the actual vibration signal, potentially causing researchers to misinterpret the mechanical behavior being studied [14].

Aliasing Mechanisms in Digital MEMS Accelerometers

In digital MEMS accelerometer systems, aliasing typically occurs through two primary mechanisms:

- Temporal aliasing results from insufficient sampling rates relative to signal dynamics, where high-frequency components fold back into the lower frequency spectrum [14].

- Spatial aliasing can occur in array-based sensing applications when sensor spacing fails to capture spatial frequency components adequately.

The practical implication of these aliasing mechanisms is that undersampled acceleration signals can misrepresent the temporal and amplitude characteristics of biological movements. As shown in Figure 2, when the sampling rate is less than twice the vibration frequency, an aliased waveform appears in the results that doesn't represent the actual vibration [14].

Comparative Analysis of Sampling Frequency Effects

Behavioral Classification Accuracy Across Taxa

Table 1: Sampling Frequency Requirements for Different Behavioral Classifications

| Organism/Context | Behavior Type | Minimum Sampling Frequency | Recommended Sampling Frequency | Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| European pied flycatcher | Swallowing food (short-burst) | 56 Hz | 100 Hz | Accurate classification of mean frequency of 28 Hz [16] |

| European pied flycatcher | Flight (rhythmic) | 12.5 Hz | 25 Hz | Adequate characterization of longer-duration movements [16] |

| Human activity recognition | Fall detection | 15-20 Hz | 20 Hz | Specificity/sensitivity >95% with convolutional neural network [17] |

| Human infants (4-18 months) | Postures & movements | 6 Hz | 13-52 Hz | Posture classification kappa=0.90-0.92; movement kappa=0.56-0.58 [8] |

| Spontaneous infant movements | Posture classification | 6 Hz | 13 Hz | Cohen kappa >0.75 maintained [8] |

| Spontaneous infant movements | Movement classification | 13 Hz | 52 Hz | Cohen kappa ~0.50-0.53 with accelerometer only [8] |

Sensor Performance Under Different Sampling Conditions

Table 2: IMU Sensor Performance Characteristics for Dynamic Measurement

| Sensor Model | Optimal Sampling Frequency Range | Shock Amplitude Accuracy | Vibration Measurement Stability | Best Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blue Trident | 1125 Hz (low-g), 1600 Hz (high-g) | Relative errors <6% | Moderate | High-precision impact analysis [18] |

| Xsens MTw Awinda | 100-240 Hz | Moderate | High stability for low-frequency vibrations | Gait analysis, running, tennis [18] |

| Shimmer 3 IMU | 2-1024 Hz (configurable) | Significant variability | Considerable signal variability | Research with post-processing capabilities [18] |

| LIS2DU12 | 25-400 Hz (filter dependent) | Good (with anti-aliasing) | Good (embedded AAF) | Battery-constrained applications [14] |

Energy Trade-offs at Different Sampling Rates

Table 3: Power Consumption Implications of Sampling Frequency Selection

| Sampling Frequency | Current Consumption | Storage Requirements | Battery Life Impact | Data Quality Trade-offs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 Hz | <1 mA (low-power mode) | Minimal | Lithium batteries >1 year | Acceptable for posture, poor for brief movements [8] [15] |

| 20 Hz | Low | Low | Extended operation | Suitable for fall detection [17] |

| 52 Hz | Moderate | Moderate | Days to weeks | Good for spontaneous movements [8] |

| 100 Hz | High (~2× 25 Hz) | High (4× 25 Hz) | Significant reduction | Necessary for short-burst behaviors [16] |

| 500 Hz | Very high | Very high | Hours to days | 2.5× oversampling for 100 Hz vibration [14] |

Experimental Protocols for Sampling Frequency Optimization

Avian Behavior Classification Protocol

The experimental protocol from the European pied flycatcher study provides a robust methodology for determining species-specific sampling requirements [16]:

- Sensor Configuration: Tri-axial accelerometers (±8 g range, 8-bit resolution) attached to the synsacrum using a leg-loop harness, recording at approximately 100 Hz initially.

- Behavioral Annotation: Synchronized stereoscopic videography at 90 frames-per-second to establish ground truth for behavior classification.

- Data Processing: Original high-frequency data systematically down-sampled to various lower frequencies (12.5 Hz to 100 Hz).

- Performance Validation: Machine learning classifiers trained and validated at each sampling frequency, with performance compared against video-annotated behaviors.

- Nyquist Determination: Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) analysis conducted on original signals to identify the highest frequency components of each behavior.

This methodology revealed that swallowing behavior (mean frequency 28 Hz) required sampling at 100 Hz (>1.4 times Nyquist frequency) for accurate classification, whereas flight could be characterized adequately at 12.5 Hz [16].

Vibration and Shock Measurement Protocol

For high-frequency impact analysis, a controlled laboratory assessment protocol was employed to evaluate sensor performance [18]:

- Experimental Setup: Electrodynamic shaker generating sine waves at varying frequencies (0.5-100 Hz for vibrations) and shock profiles with defined peak accelerations and durations.

- Sensor Mounting: Rigid attachment to minimize secondary vibrations and ensure consistent measurement conditions.

- Reference Measurements: Comparison against calibrated reference sensors to establish ground truth.

- Signal Analysis: Calculation of relative errors in amplitude and timing, assessment of signal variability across repeated trials.

- Frequency Response Characterization: Systematic testing across operational frequency ranges to identify resonant frequencies and attenuation profiles.

This protocol demonstrated that Blue Trident achieved the highest accuracy in shock amplitude and timing (relative errors <6%), while Xsens provided stable measurements under low-frequency vibrations [18].

Anti-Aliasing Filter Evaluation Protocol

To assess the effectiveness of anti-aliasing strategies, the following methodology was implemented [14]:

- Signal Generation: Production of signals with known frequency components, including harmonics beyond expected ranges.

- Filter Implementation: Application of analog anti-aliasing filters before ADC conversion in the signal chain.

- Aliasing Detection: Comparison of output spectra with input signals to identify frequency folding.

- Power Measurements: Documentation of current consumption at different output data rates with and without filtering.

- Performance Metrics: Quantitative assessment of signal fidelity, including signal-to-noise ratio and total harmonic distortion.

This approach demonstrated that embedded analog anti-aliasing filters (as in the LIS2DU12 family) enabled accurate signal capture at lower sampling rates while minimizing current consumption [14].

Visualization of Aliasing Concepts and Mitigation Strategies

Aliasing Mechanism in Signal Sampling

Diagram 1: The aliasing mechanism occurs when high-frequency signals are sampled below the Nyquist rate, causing frequency folding and distortion that compromises behavior classification accuracy.

Anti-Aliasing Filter Implementation

Diagram 2: Analog anti-aliasing filters remove high-frequency noise before ADC sampling, preventing aliasing while enabling lower sampling rates and reduced power consumption.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Solutions for Aliasing Mitigation

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Optimal Sampling Design

| Solution Category | Specific Products/Models | Key Functionality | Research Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| MEMS Accelerometers with Embedded AAF | LIS2DU12 Family | Analog anti-aliasing filter before ADC | Battery-constrained field studies requiring long deployment [14] |

| High-Performance IMU Systems | Blue Trident (Dual-g), Xsens MTw Awinda | High sampling rates (1125-1600 Hz) | High-impact biomechanics and shock measurement [18] |

| Configurable Research IMUs | Shimmer 3 IMU | Adjustable sampling (2-1024 Hz) and ranges | Methodological studies comparing sampling strategies [18] |

| Multi-Sensor Wearable Systems | MAIJU Suit (4 IMU sensors) | Synchronized multi-point sensing | Comprehensive posture and movement classification [8] |

| Vibration Validation Tools | Electrodynamic shakers | Controlled frequency and amplitude output | Sensor validation and frequency response characterization [18] |

The implications of aliasing and signal distortion when sampling below the Nyquist frequency present significant challenges for behavior classification research. The evidence compiled in this guide demonstrates that sampling requirements vary substantially depending on the specific research context:

For long-duration, rhythmic behaviors such as flight in birds or walking in humans, sampling frequencies as low as 12.5-20 Hz may suffice when using appropriate classification algorithms [16] [17]. In contrast, short-burst, high-frequency behaviors like swallowing in flycatchers or tennis impacts require sampling at 100 Hz or higher to prevent aliasing and maintain classification accuracy [16] [18].

The most effective research approach incorporates application-specific sampling strategies rather than universal solutions. Researchers should conduct pilot studies to characterize the frequency content of target behaviors, select sensors with appropriate anti-aliasing protections, and balance sampling rate decisions against power constraints and deployment duration requirements. When resources allow, oversampling at 2-4 times the Nyquist frequency provides the most robust protection against aliasing while enabling high-fidelity behavior classification across diverse movement patterns [16] [14].

The use of accelerometers for behavior classification has become a cornerstone in both clinical human research and preclinical animal studies. These sensors provide objective, continuous data on physical activity, which serves as a crucial digital biomarker for conditions ranging from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) to Parkinson's disease (PD). A critical parameter in the design of these monitoring systems is the sampling frequency, which directly influences data volume, power consumption, device size, and ultimately, the feasibility of long-term monitoring. This guide objectively compares the sampling practices and their impact on classification accuracy in human and animal research, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a synthesized overview of current experimental data and methodologies.

Sampling Frequencies in Human Activity Recognition (HAR)

Research on human subjects systematically explores how low sampling frequencies can be pushed without significantly compromising activity recognition accuracy, a key consideration for developing efficient, long-term monitoring devices.

Key Experimental Findings on Sampling Frequency

A 2025 study investigated this trade-off by having 30 healthy participants wear accelerometers at five body locations while performing nine activities. Machine-learning-based activity recognition was conducted using data down-sampled from an original 100 Hz to various lower frequencies [2].

Table 1: Impact of Sampling Frequency on Human Activity Recognition Accuracy

| Sampling Frequency | Impact on Recognition Accuracy | Key Observations |

|---|---|---|

| 100 Hz | Baseline accuracy | Original sampling rate [2]. |

| 50 Hz | No significant effect | Maintained accuracy with reduced data volume [2]. |

| 25 Hz | No significant effect | Maintained accuracy with reduced data volume [2]. |

| 20 Hz | No significant effect | Sufficient for fall detection, as noted in other studies [2]. |

| 10 Hz | No significant effect | Recommended minimum; maintains accuracy while drastically decreasing data volume for long-term monitoring [2]. |

| 1 Hz | Significant decrease | Notably reduced accuracy for activities like brushing teeth [2]. |

The study concluded that for the non-dominant wrist and chest sensor locations, a reduction to 10 Hz did not significantly affect recognition accuracy for a range of daily activities. However, lowering the frequency to 1 Hz substantially decreased the accuracy for many activities [2]. This finding is consistent with other studies suggesting that 10 Hz is sufficient for classifying activities like walking, running, and household tasks [2].

Detailed Human Research Experimental Protocol

Understanding the methodology behind these findings is crucial for evaluating their validity and applicability.

Objective: To determine the minimum sampling frequency that maintains recognition accuracy for each activity [2].

- Participants: 30 healthy individuals (13 males, 17 females), mean age 21.0 ± 0.87 years [2].

- Sensor Configuration: Participants wore five 9-axis accelerometer sensors (ActiGraph GT9X Link) positioned on the dominant wrist, non-dominant wrist, chest, hip, and thigh. Sensors were configured to a sampling frequency of 100 Hz [2].

- Activity Protocol: Participants performed nine activities in a set order, including lying supine, sitting, standing, walking, climbing/descending stairs, and brushing teeth [2].

- Data Analysis: Data from the non-dominant wrist and chest were down-sampled to 100, 50, 25, 20, 10, and 1 Hz. Machine learning models were then used for activity recognition, and accuracy was compared across the different sampling frequencies [2].

Sampling Frequencies in Animal Research

In preclinical research, particularly in rodent models of disease, accelerometry is used to distinguish between healthy and diseased states based on motor activity. The technical constraints and objectives here differ from human studies, influencing the chosen sampling frequencies.

Key Experimental Findings in Animal Models

A 2025 study on a Parkinson's disease rat model successfully distinguished between healthy and 6-OHDA-lesioned parkinsonian rats using accelerometry. The research utilized a sampling frequency of 25 Hz to capture the motor symptoms [19].

Table 2: Sampling Frequency Application in Parkinsonian Rat Research

| Research Aspect | Detail |

|---|---|

| Disease Model | 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA) unilateral lesioned male Wistar-Han rats [19]. |

| Primary Objective | Distinguish between healthy and Parkinsonian rats based on motor activity [19]. |

| Sampling Frequency | 25 Hz [19]. |

| Key Differentiating Metric | Variance of the acceleration vector magnitude: Significantly higher in sham (0.279 m²/s⁴) vs. PD (0.163 m²/s⁴) animals [19]. |

| Sensor Attachment | Wireless accelerometer in a rodent backpack, allowing unimpeded movement [19]. |

The choice of 25 Hz in this context is driven by the need to capture the more subtle and rapid movements of smaller animals while balancing the stringent energy and size constraints of the wearable device. The study found that the variance of the acceleration magnitude was 41.5% lower in the Parkinsonian rats, indicating reduced movement variability, a key digital biomarker of the disease [19].

Detailed Animal Research Experimental Protocol

The protocol for animal research highlights the unique challenges of preclinical data collection.

Objective: To establish wireless accelerometer measurements as a simple and energy-efficient method to distinguish between healthy rats and the 6-OHDA Parkinson's disease model [19].

- Subjects: Male Wistar-Han rats, comprising both 6-OHDA-lesioned (Parkinsonian) and sham-lesioned (healthy control) groups [19].

- Sensor Configuration: A wireless sensor node equipped with a MEMS accelerometer and a Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) transceiver was used. The sensor was placed in a rodent backpack, an extracorporeal attachment designed to minimize impairment of the animal's free movement [19].

- Data Collection: Acceleration signals were recorded continuously for 12 hours during the animals' active phase within their home cages. Data was sampled at 25 Hz [19].

- Data Analysis: The magnitude of the three-dimensional acceleration vector was calculated. The data was segmented, and statistical moments (mean, variance, skewness, kurtosis) were computed for these segments. The distributions of these statistics were then compared between the two classes of animals [19].

Comparative Analysis: Human vs. Animal Research Practices

Directly comparing the sampling practices reveals how the research context dictates technical choices.

Table 3: Direct Comparison of Human and Animal Research Practices

| Parameter | Human Research (HAR) | Animal Research (Parkinson's Model) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Classify specific activities (e.g., walking, brushing teeth) [2] | Distinguish healthy from diseased state [19] |

| Typical Sampling Frequencies | 10 - 100 Hz [2] | 25 Hz (in featured study) [19] |

| Recommended Minimum | 10 Hz [2] | Context-dependent; balances detail with energy constraints |

| Key Differentiating Metrics | Machine learning classification accuracy [2] | Statistical moments of acceleration (variance, skewness) [19] |

| Sensor Placement | Wrist, chest [2] | Backpack (extracorporeal), potential for implantable [19] |

| Main Driver for Low Frequency | Minimize data volume, power consumption, and device size for patient comfort and long-term monitoring [2] | Extreme energy and size constraints for unimpeded animal movement and long battery life [19] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Materials and Equipment for Accelerometer-Based Behavior Research

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| 9-Axis Accelerometer (e.g., ActiGraph GT9X Link) | Sensor for capturing tri-axial acceleration data in human research studies [2]. |

| MEMS Accelerometer | Micro-electro-mechanical system-based sensor; prized for its small size (< 4 mm³) and ultra-low power consumption (as low as 850 nA), making it ideal for animal-borne and implantable devices [19]. |

| Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) Module | Wireless transceiver for data transmission from the sensor to a computer; chosen for its energy efficiency in mobile and animal studies [19]. |

| Rodent Backpack | An extracorporeal harness system to carry the accelerometer and battery on a rat or mouse, designed to minimize impairment of natural behavior [19]. |

| 6-Hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA) | A neurotoxin used to create a unilateral lesion in the dopaminergic pathway of rats, establishing a common model for Parkinson's disease research [19]. |

| Machine Learning Classifiers (e.g., SVM, Decision Trees) | Algorithms used to classify raw or processed accelerometer data into specific activity labels in human research [2]. |

| Segmental Statistical Analysis | A processing method where continuous data is split into segments, and statistics (variance, kurtosis, etc.) are calculated for each to find movement patterns [19]. |

The current landscape of accelerometer sampling practices reveals a tailored approach based on the research domain. In human activity recognition, the drive towards unobtrusive, long-term clinical monitoring has identified 10 Hz as a robust minimum for maintaining classification accuracy while optimizing device resources. In contrast, preclinical animal research, exemplified by Parkinson's disease model studies, often employs slightly higher frequencies like 25 Hz to capture nuanced motor phenotypes under severe energy and size constraints. For researchers and drug development professionals, this comparison underscores that there is no universal "best" sampling frequency. The optimal choice is a deliberate compromise, balancing the required temporal resolution of the target behavior against the practical limitations of the sensing platform, whether it is worn by a patient or a laboratory animal.

Implementing Effective Sampling Strategies Across Research Contexts

Behavior classification using accelerometer data is a cornerstone of modern movement ecology, wildlife conservation, and precision livestock farming. The selection of an appropriate machine learning algorithm is critical to accurately interpreting animal behavior from raw sensor data. Among the numerous available algorithms, Random Forest (RF), Artificial Neural Networks (ANN), and Discriminant Analysis have emerged as prominent tools. This guide provides an objective comparison of these three algorithms, drawing on recent experimental studies to evaluate their performance in classifying behavior from accelerometer data. The analysis is situated within the broader context of optimizing accelerometer sampling frequencies, a key factor influencing classification accuracy and the practical deployment of biologging devices.

Performance Comparison of Machine Learning Algorithms

Extensive research has been conducted to evaluate the efficacy of various machine learning algorithms for behavior classification. The table below summarizes key performance metrics from recent studies that directly compared RF, ANN, and Discriminant Analysis.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Classification Algorithms

| Algorithm | Reported Accuracy | Key Strengths | Key Limitations | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest (RF) | Consistently high accuracy; e.g., 94.8% for wild boar behaviors [20] | High accuracy, robust to overfitting, provides feature importance, works well with reduced feature sets [21]. | Can be computationally intensive for on-board use; less interpretable than simpler models. | Studies requiring high out-of-the-box accuracy and where computational resources are not severely constrained. |

| Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) | High accuracy; identified as a top performer alongside RF and XGBoost [21] | High performance, suitable for complex patterns, capable of on-board classification with low runtime and storage needs [21]. | "Black box" nature, requires large amounts of data for training, complex implementation. | Complex classification tasks with large datasets and where computational efficiency on the device is critical. |

| Discriminant Analysis | High accuracy in specific contexts; e.g., most accurate for wild red deer with minmax-normalized data [6] | Simple, fast, interpretable, performs well with clear feature separation [6]. | Assumes linearity and normality of data, may struggle with highly complex or non-linear feature spaces. | Scenarios with limited computational power, for prototyping, or when model interpretability is a high priority. |

The performance of these algorithms can be significantly influenced by data pre-processing and the specific behaviors being classified. For instance, one study on wild red deer found that discriminant analysis generated the most accurate models when used with min-max normalized acceleration data and ratios of multiple axes [6]. In contrast, a broader evaluation across bird and mammal species concluded that RF, ANN, and SVM generally performed better than simpler methods like Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) [21].

Essential Experimental Protocols for Algorithm Evaluation

To ensure reproducible and valid comparisons between machine learning algorithms, researchers adhere to a common methodological framework. The following protocols are considered standard in the field.

Data Collection and Annotation

The foundation of any supervised classification model is a high-quality, ground-truthed dataset. The standard process involves:

- Sensor Deployment: Attaching tri-axial accelerometers to animals using species-appropriate harnesses, collars, or ear tags. The device's location on the body and its orientation are meticulously documented [6] [16].

- Simultaneous Observation: Collecting accelerometer data while simultaneously recording the animal's behavior through direct observation or videography. This pairs each segment of accelerometer data with a verified behavior label (e.g., lying, grazing, running) [6] [20]. Studies may use wild [6], captive [16], or semi-natural enclosure settings [20].

Data Pre-processing and Feature Engineering

Raw accelerometer data is processed to create features for machine learning models.

- Bout Segmentation: The continuous data stream is divided into fixed-length segments, or "bouts," which are assumed to represent a single behavior [21].

- Feature Calculation: For each bout, a suite of mathematical features is calculated from the raw accelerometer axes (x, y, z). Common features include mean, standard deviation, correlation between axes, and signal magnitude [21] [22]. This step transforms the raw time-series data into a feature vector that the model can learn from.

- Data Transformation: Techniques like normalization (e.g., min-max scaling) are often applied to standardize the input features, which can improve model performance and convergence [6].

Model Training and Validation

This core phase involves building and evaluating the classification models.

- Data Splitting: The labeled dataset is divided into a training set, used to teach the model, and a testing set, used to evaluate its performance on unseen data [21].

- Model Training: Each algorithm (e.g., RF, ANN, Discriminant Analysis) is trained on the feature vectors and corresponding behavior labels from the training set.

- Performance Validation: The trained models are used to predict behaviors in the withheld testing set. Performance is quantified using metrics like overall accuracy and per-behavior balanced accuracy, which is crucial for imbalanced datasets [6] [20]. Robust validation methods like leave-one-out cross-validation are often employed [22].

The following diagram illustrates this standard workflow for accelerometer-based behavior classification.

The Impact of Sampling Frequency on Classification

The sampling frequency of the accelerometer is a critical parameter that interacts with algorithm performance. The Nyquist-Shannon sampling theorem dictates that the sampling frequency must be at least twice that of the fastest movement of interest to avoid signal distortion [16]. However, practical requirements often demand higher frequencies.

- Short-Burst Behaviors: Classifying brief, rapid behaviors like a bird swallowing food (~28 Hz) requires high sampling frequencies (>100 Hz) to capture the movement accurately [16].

- Continuous Behaviors: Slower, sustained behaviors like walking or grazing can often be classified effectively with lower sampling frequencies (e.g., 5-20 Hz) [20] [16].

- Data Volume vs. Battery Life: Higher sampling frequencies generate more data, draining battery life and consuming more storage. One study found that sampling at 25 Hz more than doubled battery life compared to 100 Hz [16]. This trade-off is a key consideration for long-term deployments.

Table 2: Recommended Sampling Frequencies for Different Behavior Types

| Behavior Type | Example Behaviors | Recommended Minimum Sampling Frequency | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short-Burst/High Frequency | Swallowing, prey catching, scratching [16] | 100 Hz or higher | Necessary to capture the full waveform of very rapid, transient movements. |

| Rhythmic/Long Duration | Flight, walking, running [16] | 12.5 - 20 Hz | Lower frequencies are sufficient to characterize the dominant rhythmic pattern. |

| Postural/Low Activity | Lying, standing, sternal resting [20] | 1 - 10 Hz | Static acceleration related to posture can be reliably identified at very low frequencies. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents & Essential Materials

Table 3: Key Materials and Tools for Behavior Classification Studies

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Tri-axial Accelerometer Loggers | Core sensor measuring acceleration in three perpendicular axes (x, y, z). Often integrated into GPS collars or ear tags [6] [20]. |

| GPS/UHF/VHF Telemetry Systems | Enables remote data download from collars deployed on wild animals, crucial for long-term studies [6]. |

| High-Speed Video Cameras | Provides the "ground truth" for synchronizing observed behaviors with accelerometer signals during model training [16]. |

| R Software Environment with ML Packages | The dominant platform for analysis; includes packages for running LDA, RF (e.g., randomForest), ANN, and other algorithms [6] [20] [21]. |

| Open-Source Software (H2O, DeepLabCut) | Provides scalable machine learning platforms (H2O) and pose-estimation tools for video-based behavioral analysis [20] [23]. |

The choice between Random Forest, Artificial Neural Networks, and Discriminant Analysis is not deterministic but depends on the specific research context. Random Forest and ANN are powerful, general-purpose classifiers that deliver top-tier accuracy for a wide range of behaviors and are suitable for on-board processing. In contrast, Discriminant Analysis remains a strong candidate for specific applications where computational simplicity, speed, and interpretability are valued, and where data characteristics align with its model assumptions.

Future research directions will likely focus on improving model generalizability across individuals, populations, and environments [22], and on advancing on-board classification algorithms to enable real-time behavior monitoring with minimal power and storage requirements [21]. A nuanced understanding of the interaction between sampling frequency, target behaviors, and algorithm capability will continue to be essential for designing effective and efficient wildlife and livestock monitoring systems.

This guide provides a comparative analysis of accelerometer performance across four common body placements—wrist, hip, thigh, and ear—for behavior classification in human and animal studies. Evidence indicates that the thigh position generally delivers superior classification accuracy for fundamental postures and activities. However, the optimal configuration is highly dependent on the specific research objectives, target behaviors, and practical constraints such as subject compliance. Furthermore, sampling frequency can be strategically reduced to 10-20 Hz for many activities without significantly compromising accuracy, thereby enhancing device battery life and facilitating long-term monitoring.

The following table summarizes the key performance metrics for each sensor placement location.

| Sensor Placement | Target Activities/Behaviors | Reported Performance Metrics | Key Findings & Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thigh | Sitting, Standing, Walking/Running, Lying, Cycling [24] [25] | >99% sensitivity & specificity for PA intensity categories [25]; Cohen’s κ: 0.92 (ActiPASS) [24] | Highest accuracy for classifying basic physical activity types and postures; excellent for sedentary vs. non-sedentary behavior discrimination [25]. |

| Wrist (Non-Dominant) | Sitting, Standing, Walking/Running, Vehicle Riding, Brushing Teeth, Daily Activities [2] [26] [27] | 84.6% balanced accuracy (free-living) [26]; 92.43% activity classification accuracy [27]; Accuracy maintained down to 10 Hz [2] | Good compliance for long-term, 24-hour monitoring [26]. Performance can be comparable to hip in free-living conditions with machine learning [26]. |

| Hip | Sitting, Standing, Walking/Running, Vehicle Riding [26] [25] | 89.4% balanced accuracy (free-living) [26]; 87-97% sensitivity/specificity [25] | Traditional placement with well-established accuracy; outperforms wrist for some intensity classifications but may be less accurate than thigh [25]. |

| Ear (Animal Study) | Foraging, Lateral Resting, Sternal Resting, Lactating [20] | 94.8% overall accuracy; Balanced Accuracy: 50% (Walking) to 97% (Lateral Resting) [20] | Minimally invasive with long battery life at 1 Hz; suitable for long-term wildlife studies where recapture is difficult. Performance varies significantly by behavior [20]. |

Performance Data and Experimental Protocols

A deeper analysis of experimental data and methodologies provides critical context for the performance summaries listed above.

Thigh-Worn Accelerometer Performance

A comparative study of 40 young adults performing a semi-structured protocol demonstrated the exceptional accuracy of thigh-worn sensors coupled with machine learning models. The thigh location achieved over 99% sensitivity and specificity for classifying sedentary, light, and moderate-to-vigorous physical activity, surpassing the performance of hip and wrist placements [25]. A separate validation study of the SENS motion and ActiPASS systems on 38 healthy adults in both laboratory and free-living conditions further confirmed the high accuracy of thigh-worn sensors, reporting Cohen’s kappa coefficients of 0.86 and 0.92, respectively [24].

Impact of Sampling Frequency on Classification Accuracy

Sampling frequency is a critical parameter that directly affects data volume, power consumption, and device longevity. Research indicates that for many human activities, sampling rates can be optimized well below the high frequencies often used in commercial devices.

A 2025 study systematically evaluated this trade-off for clinical applications [2] [28]. Using data from the non-dominant wrist and chest, researchers found that reducing the sampling frequency to 10 Hz did not significantly affect recognition accuracy for a set of nine activities. However, lowering the frequency to 1 Hz decreased accuracy, particularly for dynamic activities like brushing teeth [2]. This finding is consistent with earlier research recommending sampling rates of 10-20 Hz for standard human activities [5].

The table below synthesizes key findings on sufficient sampling rates from multiple studies.

| Study & Context | Target Activities | Sufficient Sampling Frequency | Classifier Used |

|---|---|---|---|

| Okayama Univ. (2025) - Clinical HAR [2] | Lying, sitting, walking, brushing teeth, etc. | 10 Hz (maintained accuracy) | Machine Learning |

| Zhang et al. [2] | Sedentary, household, walking, running | 10 Hz (maintained high accuracy) | Logistic Regression, Decision Tree, SVM |

| Brophy et al. [2] | Walking, running, cycling | 5-10 Hz (maintained high accuracy) | Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) |

| Antonio Santoyo-Ramón et al. [2] | Activities of Daily Living (ADL), Fall | 20 Hz (sufficient for fall detection) | CNNs |

| Ruf et al. (2025) - Animal Behavior [20] | Foraging, Resting, Lactating | 1 Hz (effective for specific behaviors) | Random Forest |

Experimental Protocol Details

The following section outlines the methodologies from key studies cited in this guide, providing a blueprint for researchers to evaluate and replicate experimental designs.

Protocol 1: Sampling Frequency for Clinical HAR (Okayama University, 2025) [2] [28]

- Participants: 30 healthy adults.

- Sensor Configuration: Participants wore nine-axis accelerometers (ActiGraph GT9X Link) at five body locations. This analysis focused on the non-dominant wrist and chest, sampled at 100 Hz.

- Activities: Participants performed nine specific activities (e.g., lying, sitting, walking, brushing teeth).

- Data Processing: Raw data was down-sampled to 50, 25, 20, 10, and 1 Hz. A machine learning model was then trained and tested at each frequency to evaluate the impact on activity recognition accuracy.

Protocol 2: Free-Living Hip vs. Wrist Comparison (Ellis et al., 2016) [26]

- Participants: 40 overweight or obese women.

- Sensor Configuration: Participants wore ActiGraph GT3X+ accelerometers on the right hip and non-dominant wrist for seven consecutive days in free-living conditions.

- Ground Truth: Participants simultaneously wore a wearable camera (SenseCam) that captured first-person images approximately every 20 seconds. These images were later annotated by researchers to provide objective activity labels.

- Classification Model: A random forest classifier combined with a hidden Markov model for time-smoothing was used to classify data into four activities: sitting, standing, walking/running, and riding in a vehicle.

Protocol 3: Multi-Site Validation (Montoye et al., 2016) [25]

- Participants: 40 young adults.

- Sensor Configuration: Participants wore accelerometers on the right hip, right thigh, and both wrists during a 90-minute semi-structured protocol.

- Protocol: Participants performed 13 activities (3 sedentary, 10 non-sedentary) in a self-selected order for 3-10 minutes each.

- Criterion Measure: Direct observation was used as the ground truth for activity intensity. Machine learning models were developed for each sensor location to predict PA intensity category.

The decision-making process for selecting an accelerometer placement, based on the synthesized research, can be visualized as a logical pathway. The following diagram illustrates the key questions a researcher should ask to determine the optimal sensor configuration for their specific study.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This section catalogs essential hardware, software, and algorithms frequently employed in accelerometer-based behavior classification research, as identified in the analyzed literature.

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function / Application | Key Features / Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| ActiGraph GT9X / GT3X+ [2] [26] | Tri-axial Accelerometer | Raw acceleration data capture for activity classification. | Research-grade; configurable sampling rate; used in numerous validation studies. |

| SENS Motion System [24] | Accelerometer System (Hardware & Software) | Thigh-worn activity classification with no-code web application. | Fixed 12.5 Hz sampling; wireless data transfer; user-friendly analysis platform. |

| ActiPASS Software [24] | Classification Software | No-code analysis of thigh-worn accelerometer data based on Acti4 algorithm. | High accuracy (Cohen’s κ=0.92); graphical user interface; processes multiple data formats. |

| SenseCam / Wearable Camera [26] | Ground Truth Device | Captures first-person visual data for annotating free-living behavior. | Provides objective activity labels in unstructured environments; crucial for free-living validation. |

| Random Forest [26] [20] | Machine Learning Algorithm | Classifies activities from accelerometer feature data. | High performance in free-living studies; handles complex, non-linear relationships in data. |

| Hidden Markov Model (HMM) [26] | Statistical Model | Temporal smoothing of classified activities. | Improves prediction by modeling sequence and duration of activities over time. |

| Signal Magnitude Vector (SVMgs) [29] | Feature Extraction | Calculates a gravity-subtracted vector magnitude from tri-axial data. | Used for activity intensity estimation and cut-point methods. |

| h2o [20] | Machine Learning Platform | Open-source platform for building ML models (e.g., Random Forest). | Accessible from R; scalable for large accelerometer datasets. |

In the rapidly evolving field of behavioral classification research, establishing reliable ground truth through rigorous annotation and validation practices forms the foundation for all subsequent analysis. For researchers and drug development professionals utilizing accelerometer data, the accuracy of behavior classification models is directly dependent on the quality of the annotated data used for training and validation [30]. Behavioral annotation refers to the process of labeling raw sensor data with corresponding behavioral states, creating the reference standard that machine learning algorithms learn to recognize [31]. The validation process ensures that these classifications remain accurate and reliable when applied to new data, particularly when deploying models in real-world clinical or research settings [32].

The critical importance of this process is magnified in safety-sensitive domains. As noted in automotive perception research, inaccuracies or inconsistencies in annotated data can lead to misclassification, unsafe behaviors, and impaired sensor fusion—ultimately compromising system reliability [30]. Similarly, in pharmaceutical development and clinical research, the emergence of digital health technologies (DHTs) and their use as drug development tools has heightened the need for standardized annotation and validation frameworks that can meet regulatory scrutiny [32].

Core Principles of Behavioral Annotation

Defining Annotation Requirements and Guidelines

The foundation of any successful behavioral annotation project lies in establishing clear, comprehensive requirements and guidelines before annotation begins. Research across multiple domains demonstrates that ambiguous or incomplete annotation requirements directly contribute to inconsistent labeling, which subsequently degrades model performance [30]. Effective annotation guidelines should include several key components:

- Visual examples that illustrate both typical cases and edge cases

- Precise glossaries defining industry or domain-specific terminology

- Cross-references to existing golden datasets where available [33]

In autonomous driving systems, studies have found that ambiguity in annotation requirements represents one of the most significant challenges, particularly when dealing with complex sensor data and evolving requirements [30]. This principle applies equally to behavioral annotation from accelerometer data, where precise operational definitions of behaviors like "foraging" versus "scrubbing" or "lateral resting" versus "sternal resting" are essential for consistency [20].

Annotation Modalities and Techniques

The appropriate annotation technique varies depending on the research context, sensor type, and behavioral categories of interest:

- Video annotation provides comprehensive contextual information but requires significant resources. Frame-by-frame annotation offers the highest precision but is time-consuming, while interpolation techniques can improve efficiency for certain behavioral categories [31].

- Sensor-focused annotation links directly to accelerometer outputs but may lack contextual richness. Temporal segmentation focuses on activities that unfold over distinct periods, while activity recognition labels specific actions occurring in the data [31].

- Multi-modal approaches that combine video and sensor data often provide the most robust foundation for ground truth establishment, particularly when classifying behaviors with similar acceleration patterns but different contextual meanings [20].

Experimental Data: Sampling Frequency Impact on Classification Accuracy

Comparative Performance Across Sampling Rates

Multiple studies have systematically investigated the relationship between accelerometer sampling frequency and behavioral classification accuracy. The evidence suggests that optimal sampling rates are highly dependent on the specific behaviors being classified and the sensor placement.

Table 1: Behavioral Classification Accuracy Across Sampling Frequencies in Human Activity Recognition

| Study | Target Behaviors | Sampling Frequencies Tested | Key Findings | Optimal Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bieber et al. [2] | Lying, sitting, standing, walking, running, cycling | 1-100 Hz | Reducing frequency to 10 Hz maintained accuracy; 1 Hz decreased accuracy for many activities | 10 Hz |

| Airaksinen et al. [13] | Infant postures (7) and movements (9) | 6-52 Hz | Sampling frequency could be reduced from 52 Hz to 6 Hz with negligible effects on classifications | 6-13 Hz |