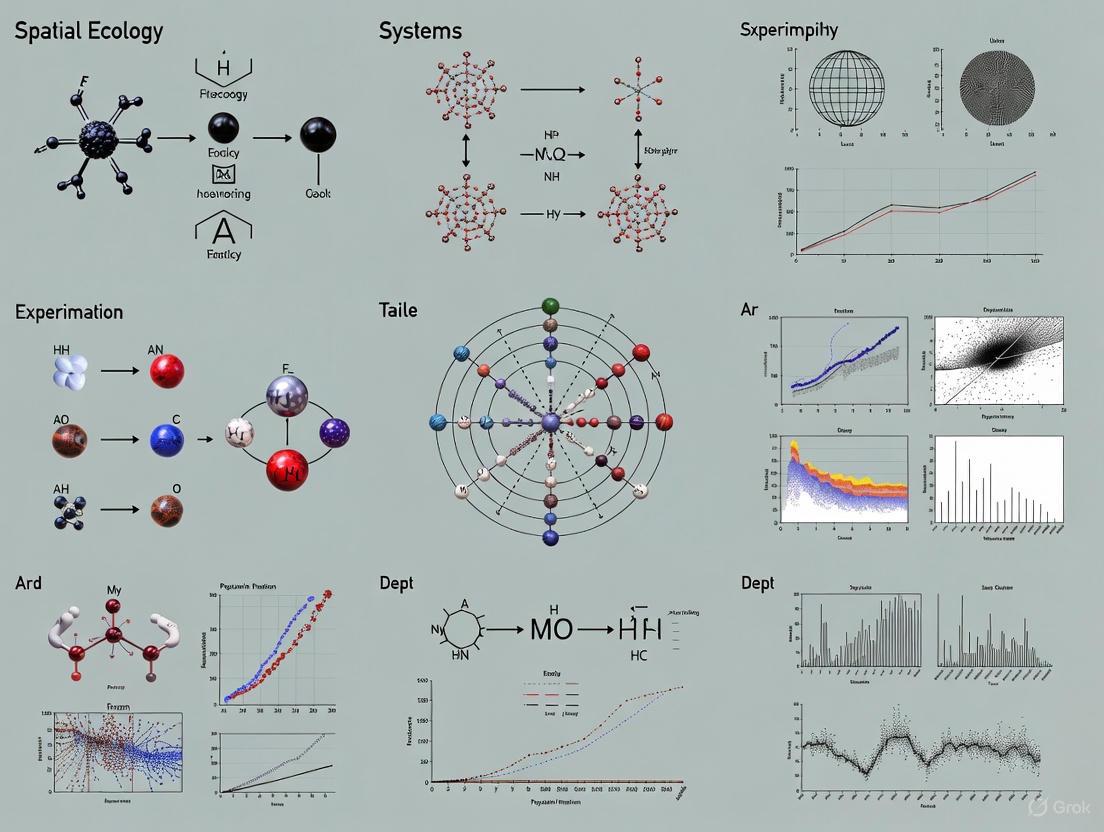

Navigating the Complexities: Key Challenges in Spatial Ecology Experimentation and Their Impact on Biomedical Research

Spatial ecology experimentation is pivotal for understanding complex biological systems, from ecosystem biodiversity to drug mechanisms of action within tissues.

Navigating the Complexities: Key Challenges in Spatial Ecology Experimentation and Their Impact on Biomedical Research

Abstract

Spatial ecology experimentation is pivotal for understanding complex biological systems, from ecosystem biodiversity to drug mechanisms of action within tissues. This article explores the foundational, methodological, and analytical challenges inherent to this field, drawing direct connections to applications in drug discovery and development. We examine core obstacles such as environmental multidimensionality, the Modifiable Areal Unit Problem (MAUP) in data analysis, and the integration of complex spatial data. For researchers and drug development professionals, we detail practical strategies for troubleshooting experimental design, optimizing technological applications like mass spectrometry imaging and spatial biology platforms, and validating findings through standardized frameworks and multimodal data integration to enhance reproducibility and translational impact.

The Core Hurdles: Understanding the Theoretical and Environmental Complexities of Spatial Systems

Embracing Multidimensionality and Combating Combinatorial Explosion

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is combinatorial explosion and why is it a critical problem in spatial ecology experiments?

Combinatorial explosion refers to the rapid growth of complexity that occurs when the number of unique experimental treatments increases exponentially with each additional environmental factor being tested [1]. In spatial ecology, this creates a fundamental research limitation because testing interactions between multiple stressors—such as temperature fluctuations, precipitation gradients, and soil quality variations—requires an unmanageable number of experimental combinations [1]. This problem is particularly acute when studying complex spatial phenomena like savanna-forest transitions, where crossing multiple bifurcation points in ecological systems creates rich, complex patterns that are difficult to model and test experimentally [2].

FAQ 2: What practical methods can researchers use to manage combinatorial complexity in multi-stressor experiments?

The most effective approach involves using response surface methodologies where two primary stressors are identified and systematically varied to create response landscapes rather than traditional one-dimensional response curves [1]. This technique allows researchers to model complex interactions while maintaining experimental feasibility. Additionally, employing dimension reduction techniques and clustering in spatial data analysis can help identify key variable interactions before designing complex experiments [3].

FAQ 3: How can visualization tools help researchers comprehend multidimensional spatial data without cognitive overload?

Modern geovisualization tools like Variable Mapper enable simultaneous visualization of up to six variables in a manageable format, using techniques such as small multiples, coordinated views, and interactive filtering [3]. These tools help researchers identify spatial patterns across multiple variables while managing the cognitive load, as human visual perception is typically limited to distinguishing four to six variables simultaneously [3]. Effective multivariate visualization combines color, size, rotation, and other visual variables to represent different data dimensions on spatial maps [4].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Problem 1: Inability to discern meaningful patterns from complex multivariate datasets.

Solution: Implement visual clustering techniques and dimension reduction methods before detailed analysis. Use tools that support side-by-side comparison of spatial variables through small multiple maps, which facilitate pattern recognition across multiple dimensions without visual overload [3]. For spatial data, ensure your visualization tool uses coordinated views where selections in one visualization automatically filter representations in others.

Problem 2: Experimental designs becoming unmanageably large with multiple environmental factors.

Solution: Adopt a response surface methodology focusing on two primary stressors initially, then sequentially add dimensions [1]. Utilize fractional factorial designs that test the most critical interactions rather than full combinatorial spaces. Implement adaptive experimental designs that use early results to refine subsequent treatment combinations.

Problem 3: Difficulty representing more than three variables simultaneously in spatial analyses.

Solution: Employ multivariate visualization techniques that combine multiple visual variables such as color, size, and rotation [4]. For example, representing weather data with rotation for wind direction, size for wind speed, and color for temperature enables effective representation of three data dimensions simultaneously [4]. Ensure sufficient contrast between visual elements and avoid color combinations that impair interpretation.

Experimental Protocols for Multidimensional Research

Protocol 1: Response Surface Methodology for Multiple Stressors

- Identify Primary Stressors: Select the two most significant environmental factors based on preliminary studies or literature review [1]

- Design Gradient Treatments: Establish 5-7 gradient levels for each primary stressor rather than simple presence/absence treatments

- Measure Response Variables: Record ecological responses at each combination point, focusing on key metrics like biodiversity indices, population densities, or physiological measurements

- Construct Response Surface: Use interpolation techniques to create a continuous response landscape from discrete measurements

- Validate Model Predictions: Test model predictions at intermediate points not included in initial experimental design

Protocol 2: Spatial Gradient Analysis Across Environmental Transitions

- Site Selection: Identify natural environmental gradients such as rainfall gradients, elevation transects, or urbanization intensity gradients [2]

- Sampling Design: Establish sampling points along the gradient continuum with appropriate replication

- Multivariate Data Collection: Record both environmental variables and ecological responses at each sampling point

- Spatial Pattern Analysis: Use spatial statistics to identify transitions, thresholds, and nonlinear responses along gradients

- Model Fitting: Apply spatial autoregressive models or generalized additive models to characterize responses to multiple simultaneous gradients

Experimental Workflow Visualization

Data Management Strategy for Complex Experiments

Quantitative Complexity of Combinatorial Experiments

Table 1: Growth of Experimental Complexity with Additional Factors

| Number of Factors | Number of Treatment Levels | Possible Unique Combinations | Experimental Feasibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 3 each | 9 | High |

| 3 | 3 each | 27 | Moderate |

| 4 | 3 each | 81 | Challenging |

| 5 | 3 each | 243 | Limited |

| 6 | 3 each | 729 | Impractical |

Table 2: Comparison of Experimental Design Strategies for Multidimensional Ecology

| Design Approach | Variables Accommodated | Combinatorial Control | Implementation Complexity | Analytical Power |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical ANOVA | 2-3 factors | Limited | Low | Moderate |

| Response Surface | 2 primary + 2 secondary | High | Moderate | High |

| Fractional Factorial | 4-6 factors | Moderate | High | Moderate |

| Gradient Analysis | Natural environmental variation | High | Low | High |

Research Reagent Solutions for Spatial Ecology

Table 3: Essential Resources for Multidimensional Spatial Ecology Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tool/Technology | Function in Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental Sensors | Automated data loggers | Capture environmental variability | Field measurements across spatial gradients |

| Spatial Analysis Software | GIS with multivariate capabilities | Visualize and analyze spatial patterns | Identifying savanna-forest boundaries [2] |

| Statistical Platforms | R with spatial packages | Model complex interactions | Response surface analysis [1] |

| Visualization Tools | Variable Mapper | Simultaneous display of multiple variables | Exploring urban superdiversity and liveability [3] |

| Experimental Systems | Mesocosms with environmental control | Test multiple stressor interactions | Aquatic ecosystem responses to global change [1] |

Confronting Spatial Heterogeneity and Environmental Gradients

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: Our experimental tiles for testing substrate heterogeneity are showing inconsistent community colonization compared to controls. What could be the cause? A: Inconsistent colonization is often due to unintended variations in tile surface area or material. The experiment in Bracelet Bay used paired 15x15cm limestone tiles where heterogeneous tiles had pits drilled into them, but the total surface area was statistically indistinguishable from the flat control tiles due to natural variability from manual cutting [5]. Ensure your manufacturing process is standardized. Also, verify that you are regularly clearing surrounding canopy algae (like fucoids) from the tiles, as these can alter local conditions such as temperature and wave disturbance, leading to confounding effects [5].

Q2: We are seeing high variability in population stability metrics across our heterogeneous experimental units. Is this expected? A: Yes, this can be expected. Heterogeneity creates refugia that enhance population stability for some stress-sensitive species [5]. However, it can also suppress dominant species and consumers, which might otherwise have a stabilizing effect on the community [5]. Therefore, the net effect on stability is the result of these counteracting pathways. Your results may show high variability as these opposing forces (both stabilising and destabilising) play out.

Q3: What is the best method for sampling community cover on experimental tiles to capture both canopy and understorey species? A: Employ a stratified sampling approach using image analysis [5]. This involves:

- Canopy Species: Take pictures and measure species cover using image analysis software (e.g., Adobe Photoshop) [5].

- Understorey Species: Take separate pictures for the understorey and estimate species cover using point-count image subsampling. Identify all organisms beneath a standard grid of points (e.g., 500 points per image) [5].

Q4: How long should a field experiment on heterogeneity and community stability run to yield reliable data? A: Multi-year data is crucial to capture temporal stability and account for seasonal variations and long-term community dynamics. The foundational experiment in this field ran for 35 months, with seasonal sampling yielding 11 time points per experimental unit [5]. A minimum of 2-3 years is recommended for assessing multi-year temporal stability.

Experimental Protocol: Testing Heterogeneity Effects on Rocky Shores

Title: Protocol for Assessing Community Stability on Artificial Substrates of Varying Heterogeneity.

Objective: To quantify the effects of small-scale substrate heterogeneity on the temporal stability of intertidal communities along an environmental stress gradient.

Methodology Summary:

This protocol is based on a 35-month field experiment conducted on a rocky shore [5].

Tile Preparation:

- Create paired sets of experimental tiles from a consistent material like limestone.

- Non-heterogeneous Tiles: Flat, smooth-surfaced tiles (15cm x 15cm).

- Heterogeneous Tiles: Tiles of the same dimensions with a standardized configuration of large, medium, and small pits drilled into them to mimic natural topographic variation [5].

- Critically, verify that the total surface area does not differ significantly between the two tile types, ensuring the test is of heterogeneity, not area.

Experimental Deployment:

- Select a site with a clear environmental gradient (e.g., an intertidal zone with emersion stress from high to low shore).

- Deploy tile pairs (one flat, one pitted) at multiple stations (e.g., 35 stations) along several transects within the study area [5].

- Secure tiles to exposed rock surfaces.

Site Maintenance:

- Regularly clear canopy-forming algae (e.g., fucoids) from the immediate area surrounding the tiles to prevent them from altering tile conditions through shading, whiplash, or wave attenuation [5].

Data Collection:

- Sample tiles seasonally during low tide over multiple years.

- Use the stratified image analysis method described in FAQ #3 to quantify percent cover of all species in both canopy and understorey strata [5].

Data Analysis:

- Calculate temporal stability metrics for populations and the entire community.

- Use structural equation modelling (SEM) to disentangle the contributions of different pathways through which heterogeneity affects stability (e.g., species richness, asynchrony, dominance, consumer pressure) [5].

Table 1: Counteracting Pathways Through Which Heterogeneity Influences Community Stability [5]

| Pathway | Effect on Stability | Proposed Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Provision of Refugia | Increases | Buffers environmental disturbances, enhancing population-level stability for stress-sensitive species. |

| Increased Species Richness & Asynchrony | Increases | Creates varied niches, supporting more species whose asynchronous fluctuations buffer community-level variability. |

| Reduction of a Dominant Species | Decreases | Heterogeneous niches reduce competitive exclusion, suppressing a dominant species that would otherwise stabilize community composition. |

| Suppression of Consumers | Decreases | Physical patchiness disrupts predator movement and access to prey, reducing top-down control that can stabilize interactions. |

Table 2: Key Specifications from the Rocky Shore Heterogeneity Experiment [5]

| Parameter | Specification |

|---|---|

| Experiment Duration | 35 months (May 2019 - April 2022) |

| Sampling Frequency | Seasonal (11 time points per tile) |

| Tile Material | Limestone |

| Tile Dimensions | 15 cm x 15 cm |

| Number of Tile Pairs | 35 |

| Key Measured Variables | Species percent cover (canopy & understorey), population stability, species richness, asynchrony |

Experimental Workflow and Stability Pathways

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Rocky Shore Heterogeneity Experiments

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Limestone Tiles | Artificial substrates that serve as standardized, replicable surfaces for community colonization and experimental manipulation (e.g., drilling pits for heterogeneity) [5]. |

| Pitted/Heterogeneous Tiles | Experimental units with drilled pits that create topographic heterogeneity, mimicking natural microhabitats and providing refugia from environmental stress [5]. |

| Digital Camera | Equipment for capturing high-resolution images of experimental tiles for subsequent stratified analysis of canopy and understorey species cover [5]. |

| Image Analysis Software | Software (e.g., Adobe Photoshop) used to measure percent cover of canopy species from digital images and facilitate point-count subsampling for understorey species [5]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the Modifiable Areal Unit Problem (MAUP) in simple terms?

The Modifiable Areal Unit Problem (MAUP) is a source of statistical bias that occurs when the results of your spatial analysis change based on how you choose to aggregate your point data into geographic units (like districts, census tracts, or grid cells) [6] [7]. It means that your conclusions can be influenced by the arbitrary scale (size) and shape of your analysis units, not just the underlying data itself [8] [9].

2. What are the two main components of MAUP?

MAUP manifests through two distinct effects [7]:

- The Scale Effect: Different results emerge when the same data is aggregated into units of different sizes (e.g., census tracts vs. counties) [6] [8].

- The Zoning Effect: Different results emerge when data is grouped into different configurations of units at the same scale (e.g., different arrangements of grid cells of the same size) [6] [10].

3. Why should spatial ecologists be concerned about MAUP?

MAUP is critical in spatial ecology because it can lead to spurious relationships and misinterpretations of spatial patterns [10]. For instance, the observed relationship between an environmental factor (like NDVI) and an ecological outcome can be artificially strong or weak depending on the spatial resolution and zoning of your data [10]. This can directly impact the effectiveness of management and conservation decisions [11].

4. How can I test if my analysis is sensitive to MAUP?

Conducting a MAUP sensitivity analysis is recommended [6]. This involves running your same analysis multiple times using different, equally plausible scales and zoning schemes. If your results or key parameters (like correlation coefficients) change significantly, your study is sensitive to MAUP, and you should report this uncertainty.

5. Are there any statistical solutions to MAUP?

While no single method completely eliminates MAUP, several approaches can help manage it. These include using Bayesian hierarchical models to combine aggregated and individual-level data, focusing on local spatial regression instead of global models, and developing scale-independent measures, such as those considering fractal dimension [6].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inconsistent or Unstable Correlation/Covariance Estimates

Problem: The correlation between two spatial variables (e.g., pollution levels and illness rates) changes dramatically when you analyze your data at different aggregation levels.

Diagnosis: This is a classic symptom of the scale effect of MAUP. Generally, correlation tends to increase as the size of the areal units increases [6].

Solution:

- Acknowledge the Problem: Do not report results from a single, arbitrary scale.

- Perform Sensitivity Analysis: Re-run your correlation analysis across a spectrum of scales (e.g., 50m, 100m, 200m, 500m grids) [11]. Report the range of correlation coefficients you obtain.

- Use Robust Methods: Consider correcting your variance-covariance matrix using samples from individual-level data, if available [6].

- Report with Transparency: Clearly state the scale(s) used in your analysis and the potential for MAUP-induced bias in your conclusions.

Issue 2: Model Outputs Lead to Misleading Management Decisions

Problem: Your habitat distribution models predict vastly different areas of suitable habitat at different spatial resolutions, leading to uncertainty about where to focus conservation efforts.

Diagnosis: This is a direct consequence of MAUP on model outputs and subsequent decision-making [11]. Coarser resolutions often lead to an oversimplification of the modelled extent.

Solution:

- Match Scale to Decision Context: Use coarse-resolution data for strategic, large-scale policy decisions, but insist on finer-resolution data for consenting or managing individual activities [11].

- Compare Model Performance: Evaluate your model's performance (e.g., AUC, precision) across multiple spatial resolutions. The table below illustrates how model performance and output can vary with resolution, using a marine conservation example [11]:

Table 1: Illustrative Example of Model Output Variation with Spatial Resolution for a Protected Marine Habitat

| Spatial Resolution | Model Performance (AUC) | Modelled Habitat Coverage (km²) | Suggested Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| 50 m | 0.89 | 15.5 | Local management & individual activity consenting |

| 100 m | 0.85 | 18.2 | Regional planning |

| 200 m | 0.82 | 22.1 | Regional planning |

| 500 m | 0.75 | 28.7 | National / strategic policy |

Issue 3: Suspected Zoning Effect (Gerrymandering in Analysis)

Problem: You suspect that the way boundaries are drawn (even unintentionally) is creating a false pattern or hiding a real one in your data.

Diagnosis: This is the zoning effect, where the configuration of boundaries at a fixed scale alters analytical results [8] [9]. This is analogous to gerrymandering in elections.

Solution:

- Test Alternative Zoning Schemes: If your data is aggregated into custom zones (e.g., watersheds, management areas), reconfigure them into several alternative, equally justifiable schemes and re-run your analysis.

- Use Non-arbitrary Units: Where possible, use zoning units based on "natural" boundaries relevant to your ecological question (e.g., based on income and unemployment levels in human ecology, or soil and elevation in landscape ecology) [9]. One study found that the relationship between pollution and illness was strongest in "natural neighborhoods" compared to government-delineated census tracts [9].

- Implement a Zoning Experiment: Systematically create multiple random aggregations of your base data at the same scale to quantify the variability introduced by the zoning effect [6].

Experimental Protocols for MAUP Investigation

Protocol 1: Quantifying the Scale and Zoning Effects

This protocol provides a methodology to empirically measure the impact of MAUP on your spatial dataset.

1. Hypothesis: The statistical relationship between variable X (e.g., nutrient load) and variable Y (e.g., algal bloom intensity) is sensitive to the scale and zoning of data aggregation.

2. Experimental Workflow:

3. Materials and Data:

- High-resolution point or individual-level data for your variables of interest.

- GIS software (e.g., ArcGIS, QGIS) with geoprocessing tools for aggregation.

- Statistical software (e.g., R, Python with Pandas/GeoPandas).

4. Procedure:

- For the Scale Effect: Using a grid-based approach, aggregate your base data into a series of regular grids of increasing cell size (e.g., 50m, 100m, 200m, 500m). For each grid, calculate the summary statistics of interest (e.g., global mean, correlation between variables, regression slope).

- For the Zoning Effect: Select one specific scale (e.g., 100m grid). Create several alternative aggregations by shifting the grid origin or by using alternative zoning systems (e.g., hexagons, watershed boundaries). Calculate the same statistics for each of these zoning schemes.

- Analysis: Plot the calculated statistics (e.g., correlation coefficient) against the scale of aggregation and across the different zoning schemes. The resulting variance demonstrates the influence of MAUP. Report the upper and lower bounds of your findings [6].

Protocol 2: MAUP-Sensitive Habitat Distribution Modeling

This protocol integrates MAUP testing into a standard species distribution modeling workflow.

1. Hypothesis: The predicted spatial extent and location of a key habitat are significantly affected by the spatial resolution of the input environmental data.

2. Workflow Diagram:

3. Materials:

- Species occurrence data (presence/absence or presence-only).

- Environmental predictor rasters (e.g., temperature, bathymetry, vegetation index) at their finest available resolution.

- Species distribution modeling software (e.g., MaxEnt, R packages

dismoorSDM).

4. Procedure:

- Resample all environmental predictor rasters to a common set of coarser resolutions (e.g., 50 m, 100 m, 200 m, 500 m) [11].

- Run your chosen distribution model (e.g., MaxEnt) separately for each set of resolution-matched predictors.

- For each model, record performance metrics (e.g., Area Under the Curve - AUC) and calculate the total area of predicted suitable habitat.

- As shown in Table 1, compare the results across resolutions. The divergence in predicted area and model performance highlights the MAUP's impact. Use this analysis to justify the choice of an appropriate, scale-specific model for your management objective [11].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Investigating MAUP

| Tool / Resource | Function in MAUP Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| GIS Software (e.g., ArcGIS, QGIS) | To aggregate point data, create multiple zoning schemes, and perform spatial overlays. | Generating a series of grid layers at different resolutions for scale effect analysis [6]. |

| Spatial Statistics Packages (e.g., R 'spdep', Python 'PySAL') | To calculate spatial autocorrelation, local indicators of spatial association (LISA), and spatial regression. | Quantifying how spatial autocorrelation changes with aggregation scale [10]. |

| Scripting Language (e.g., Python with ArcPy/GeoPandas) | To automate the data simulation and re-aggregation process for robust sensitivity analysis [6]. | Running a Monte Carlo simulation to create hundreds of alternative zoning schemes. |

| Data Simulation Tools | To generate synthetic spatial data with known properties, allowing for controlled MAUP experiments [6]. | Isolating the effect of aggregation from other confounding factors present in real-world data. |

| Bayesian Hierarchical Modeling Frameworks (e.g., R 'INLA') | To integrate data from multiple levels of aggregation and provide a formal framework for accounting of uncertainty. | Combining fine-scale survey data with coarse-scale census data for ecological inference [6]. |

Moving Beyond Classical Model Organisms for Generalizable Insights

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are the main advantages of using non-model organisms in research? Non-model organisms are invaluable for studying biological traits absent in classical models (e.g., regeneration in salamanders), evolutionary questions requiring specific phylogenetic positions, and for accessing unique metabolites or commercial applications. They often provide a less competitive research environment with high potential for novel, highly-cited discoveries [12] [13] [14].

My research requires a high-quality genome assembly. What is the recommended strategy? For a new reference genome, long-read sequencing technologies are the method of choice as they enable chromosome-scale scaffolds. While pure short-read assemblies are more fragmented, they can be a viable option if DNA quality is poor, funding is limited, or if the primary research goal is focused on coding regions and population genomics [15].

How can I perform functional analysis without dedicated databases for my organism? Tools like NoAC (Non-model Organism Atlas Constructor) can automatically build knowledge bases by leveraging orthologous relationships between your non-model organism and well-annotated reference model organisms. This infers functional annotations like Gene Ontology terms and pathways without requiring programming skills [16].

What are the key practical challenges I should anticipate? Be prepared for challenges including a lack of established protocols, difficulties in culturing the organism, slow life cycles, unsequenced genomes, and the unavailability of commercial kits, mutants, or plasmids from stock centers. Significant time must be invested in optimizing basic laboratory methods [13] [17].

Troubleshooting Guides

Genome Sequencing and Assembly

| Challenge | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Highly fragmented assembly | Use of short-read sequencing technologies; complex, repeat-rich genome [15]. | Employ long-read sequencing (PacBio, Oxford Nanopore). Use additional scaffolding information from techniques like Hi-C [15]. |

| Difficulty obtaining high molecular weight (HMW) DNA | Tissue source is a small organism; suboptimal DNA extraction techniques [15]. | Optimize DNA extraction protocols specifically for HMW DNA. Consider pooling individuals if the organism is very small [15]. |

| Missing or poor functional annotation | Lack of curated databases and literature for the organism [16]. | Use orthology-based annotation tools like NoAC. Perform de novo functional annotation using combined evidence from BLAST and EggNog mappings [12] [16]. |

Pathway and Functional Analysis

| Challenge | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Missing pathway annotations | Species-specific pathway databases are unavailable [12]. | Use software with "Combined Pathway Analysis" features (e.g., OmicsBox). Select a closely related model organism as a reference for mapping [12]. |

| High proportion of unannotated genes | Evolutionary distance from well-annotated models; novel genes [15] [16]. | Perform de novo transcriptome assembly. Use a combination of homology-based and ab initio gene prediction methods. |

Experimental Design in Spatial Ecology

| Challenge | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| 'Combinatorial explosion' of treatments | Testing multiple environmental stressors simultaneously leads to an exponential increase in treatment combinations [1]. | Use response surface methodologies where two primary stressors are identified. Focus on key interactions rather than testing all possible combinations [1]. |

| Unrealistic environmental conditions | Experiments use constant average conditions instead of natural variability [1]. | Incorporate environmental fluctuations (e.g., temperature, rainfall gradients) into the experimental design, considering their magnitude, frequency, and predictability [2] [1]. |

| Pseudoreplication in landscape experiments | Confusing sampling units with experimental units [18]. | Clearly define the experimental unit as the smallest division that can receive different treatments. Ensure statistical analysis is performed at the correct (experimental unit) level [18]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1:De NovoTranscriptome Assembly and Analysis for Non-Model Organisms

This protocol is adapted from a case study on salamander limb regeneration [12].

1. Data Collection and Preprocessing:

- Obtain RNA-seq reads from relevant tissues and experimental conditions.

- Perform quality assessment using a tool like FastQC. Check for per-base sequence quality and adapter content. High-quality data may not require additional trimming.

2. De Novo Transcriptome Assembly:

- Use a assembler like Trinity with default parameters.

- Filter the resulting contigs by length (e.g., discard sequences < 200 bp).

- Reduce redundancy by clustering sequences with a tool like CD-HIT.

3. Contaminant Removal:

- Perform taxonomic classification using Kraken against a standard database.

- Discard sequences classified as microorganisms (Bacteria, Archaea, Viruses).

- Retain sequences classified as "unknown" or belonging to the target kingdom (e.g., Animalia).

- Perform a BLAST search against a custom database of unwanted host sequences (e.g., ribosomal and mitochondrial genes) and remove positive hits. The remaining sequences form the reference transcriptome.

4. Transcript Abundance and Differential Expression:

- Map RNA-seq reads back to the reference transcriptome using a tool like RSEM to estimate transcript abundance.

- Perform differential expression analysis using a tool like EdgeR or DESeq2, applying appropriate significance thresholds (e.g., FDR < 0.05).

5. Functional and Pathway Analysis:

- For non-model organisms, use a combined pathway analysis approach.

- Input the assembled transcriptome and the list of differentially expressed genes into a platform like OmicsBox.

- Configure the analysis to use the closest available model organism for pathway mapping (e.g., Xenopus tropicalis for amphibians). The software will map sequences to pathways and perform enrichment analysis using Fisher's exact test or GSEA.

Protocol 2: Orthology-Based Functional Genome Annotation with NoAC

This protocol uses the NoAC tool to build a functional knowledge base [16].

1. Prepare Required Genome Files:

- Compile the following files for your non-model organism:

- Gene table (GFF/GTF format)

- Genome annotation file

- Genome sequences (FASTA)

- Transcript sequences (FASTA)

- Protein sequences (FASTA)

2. Select Reference Model Organism:

- Choose an evolutionarily close, well-annotated reference model organism (e.g., for a butterfly, select Drosophila melanogaster).

3. Run NoAC:

- Install the NoAC Docker container.

- Launch the local NoAC service and access the web interface.

- Upload the genome files from Step 1.

- Select the reference model organism from Step 2.

- Execute the one-click processing. NoAC will automatically identify orthologs, infer functional annotations (GO terms, pathways, protein interactions), and generate a searchable knowledge base with a query interface.

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function | Consideration for Non-Model Organisms |

|---|---|---|

| Long-read Sequencer (PacBio, Nanopore) | Generates long sequencing reads essential for assembling contiguous, high-quality genomes, resolving repetitive regions [15]. | Method of choice for de novo reference genomes; cost and computing resources required are higher [15]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Enables precise gene editing for functional studies; can be used for gene knockout and CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) [14]. | Requires prior development of transformation/transfection protocols and identification of functional promoters for the target organism [14] [17]. |

| Orthology-Based Annotation Tool (NoAC) | Infers gene function, pathways, and protein interactions by mapping orthologs from a well-studied reference organism [16]. | A user-friendly solution that requires no programming skills; dependent on the quality of the chosen reference organism's annotations [16]. |

| Baby Boom Transcription Factor | A chimeric transcription factor that, when expressed, induces shoot production in plants, helping overcome recalcitrance to tissue culture [14]. | Crucial for domesticating and genetically engineering non-model plant species that are difficult to culture [14]. |

| Methylation Enzymes | When expressed in E. coli during cloning, these enzymes modify plasmid DNA to mimic the methylation patterns of the target non-model bacterium [14]. | Helps overcome restriction-modification systems in non-model bacteria that would otherwise degrade foreign DNA, enabling genetic transformation [14]. |

Workflow Visualizations

Genome Assembly and Annotation Pathway

Pathway Analysis for Non-Model Organisms

From Theory to Bench: Technological Tools and Experimental Frameworks for Spatial Data

Platform-Specific Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

This section provides targeted support for common experimental challenges, helping to ensure the success and reproducibility of your spatial biology work.

10x Visium Platform

Q: What are the key considerations for choosing between the Visium and Visium HD workflows?

- A: Your choice depends on your required spatial resolution and sample type. The standard Visium assay has a resolution of 55 µm and requires the CytAssist instrument to apply gene expression probes to the slide, which is especially crucial for FFPE samples. Visium HD, with its finer 2 µm resolution, uses the same CytAssist-powered workflow but a different slide architecture to achieve near-single-cell scale resolution for deeper spatial discovery [19] [20].

Q: What software is available for data analysis?

- A: 10x Genomics provides Space Ranger, a pipeline to process spatial sequencing data alongside imaging data in minutes, often without requiring command-line expertise. For data visualization and exploration, Loupe Browser allows you to interactively visualize thousands of spatially variable genes and define cell types by region and morphology [19].

GeoMx DSP Platform

Q: How can I practice region of interest (ROI) selection without running a full experiment?

- A: Use the "Scan only" feature. This allows you to scan your slides and select ROIs without proceeding to collection, which is ideal for evaluating tissue staining conditions or practicing ROI selection. These "scan only" files can be transferred to a full experiment later using the ROI transfer function [21].

Q: My instrument encountered a critical error during collection. How do I protect my samples?

- A: If a critical error occurs, you should safely remove your slides to prevent them from drying out. As an administrator, you can home the hardware and unlock the door via the Administration tab. As a general user, you can perform a system shutdown. Once retrieved, store the slides appropriately: RNA slides in 2X SSC at 4°C, and protein slides in 1X TBS-T at 4°C, both protected from light [21].

Q: The instrument will not be used for over two weeks. What should I do?

- A: Run the hibernation protocol to prevent crystallization or salt accumulation in the fluidic lines. This involves switching the instrument buffers to DEPC-treated water and flushing the system. A service engineer is required to move the instrument any significant distance due to a critical leveling process [21].

COMET Platform

Q: What are the advantages of antibody panel development on COMET?

- A: The platform allows for rapid and flexible panel development using standard, label-free primary antibodies, eliminating the need for time-consuming and variable conjugation or barcoding steps. You can transfer existing IHC/IF antibody knowledge to your COMET library, and the system can generate hyperplex protocols automatically in just a few clicks [22].

Q: Is the platform compatible with multiomics assays?

- A: Yes, COMET supports fully automated spatial multiomics. It can simultaneously detect any RNA and protein targets on the same tissue section using RNAscope HiPlex Pro and off-the-shelf non-conjugated primary antibodies, providing a deeper understanding of cellular processes with subcellular resolution [22].

Q: What image analysis options are available?

- A: COMET is compatible with several industry-standard image analysis platforms. Lunaphore provides HORIZON, an intuitive entry-level tool for users with no coding experience. The platform also has proven compatibility with Oncotopix Discovery, HALO & HALO AI, Nucleai AI-powered Solutions, and QuPath [22].

Performance Comparison of Spatial Platforms

Independent benchmarking studies provide critical, data-driven insights for platform selection. The following tables summarize key performance metrics from recent evaluations.

Table 1: Benchmarking Results of Imaging-Based Spatial Transcriptomics Platforms in FFPE Tissues

| Performance Metric | 10X Xenium | Nanostring CosMx | Vizgen MERSCOPE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transcript Counts per Gene | Consistently higher [23] | High total transcripts [24] | Lower in comparison [23] |

| Concordance with scRNA-seq | High correlation [23] [24] | Substantial deviation from scRNA-seq [24] | Data not specified in benchmark |

| Cell Sub-clustering Capability | Slightly more clusters [23] | Slightly more clusters [23] | Fewer clusters [23] |

| Cell Segmentation | Improved with membrane stain [23] | Varies [23] | Varies [23] |

Table 2: Technical Comparison of Major Spatial Biology Platforms

| Platform | Technology Category | Spatial Resolution | Key Application Strength |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10x Visium / Visium HD | Sequencing-based (NGS) | 55 µm (Visium), 2 µm (HD) [20] | Unbiased, whole transcriptome discovery [19] |

| GeoMx DSP | Sequencing-based (NGS/nCounter) | Region of Interest (ROI) selection [20] | Morphology-driven, high-plex profiling of user-defined regions [21] |

| COMET | Imaging-based (Multiplex IF) | Subcellular [22] | Highly multiplexed protein detection with label-free antibodies [22] |

| Xenium | Imaging-based (ISS/ISH) | Single-cell [20] | Targeted gene expression with high sensitivity and single-molecule resolution [23] |

Experimental Workflow Diagrams

Understanding the core technological workflows is essential for robust experimental design and troubleshooting in spatial ecology research.

Visium HD Workflow

GeoMx DSP Workflow

COMET Automated Multiplexing Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

This table outlines essential materials and their functions to guide your experiment planning.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Their Functions in Spatial Biology

| Reagent / Material | Function | Platform Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Visium Spatial Slide | Contains ~5,000 barcoded spots with oligo-dT primers for mRNA capture [20]. | 10x Visium |

| CytAssist Instrument | Enables a histology-friendly workflow; transfers probes from standard glass slides to Visium slide [19]. | 10x Visium (FFPE) |

| Label-Free Primary Antibodies | Standard, non-conjugated antibodies used for highly multiplexed protein detection [22]. | Lunaphore COMET |

| SPYRE Signal Amplification Kit | Amplifies signal of low-expressed or hard-to-detect markers without compromising accuracy [22]. | Lunaphore COMET |

| Morphology Markers | Antibodies or stains (e.g., PanCK, CD45) used to visualize tissue anatomy for ROI selection [21]. | GeoMx DSP |

| GeoMx DSP Buffer Kits | Manufacturer-provided buffers to prevent microbial growth and fluidic line clogging [21]. | GeoMx DSP |

| RNAscope HiPlex Pro | Assay for automated, multiplexed RNA detection in a multiomics workflow [22]. | Lunaphore COMET |

Core Principles of MSI

Mass Spectrometry Imaging (MSI) is a powerful, label-free technique that visualizes the spatial distribution of molecules—such as drugs, metabolites, lipids, and proteins—directly from tissue sections. By collecting mass spectra point-by-point across a defined grid on a sample surface, MSI generates heat maps that reveal the relative abundance and location of thousands of molecular species in a single experiment [25]. This capability to localize compounds in situ is invaluable for spatial ecology experimentation, as it allows researchers to understand how drugs and endogenous metabolites distribute within complex biological environments without prior knowledge of the system [26].

The two primary operational modes in MSI are:

- Microprobe Mode: A focused ionization beam analyzes specific regions sequentially, storing each mass spectrum with its spatial coordinates. The sample or beam is moved to scan the entire area, and images are reconstructed by combining the individual spectra [26] [27].

- Microscope Mode: A position-sensitive detector measures the spatial origin of ions generated from the sample surface. This method can analyze multiple pixels in a single sampling event but is limited by the depth of field of the microscope's ion optics [26].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Sample Preparation Fundamentals

Proper sample preparation is the most critical step for a successful MSI experiment, as it preserves molecular integrity and spatial localization [25].

- Tissue Collection and Stabilization: Fresh tissue samples should be flash-frozen to halt enzyme activity and prevent analyte degradation or delocalization. Formalin fixation is typically not recommended for most molecules as it causes cross-linking, though it can be used for some lipid analyses [25].

- Sectioning and Mounting: Frozen tissues are thinly sectioned (typically 6–20 µm thickness) using a cryostat and thaw-mounted onto an appropriate substrate (e.g., a glass microscope slide or indium tin oxide (ITO)-coated slide). For fragile tissues, gelatin embedding is recommended; Optimal Cutting Temperature (OCT) compound should be avoided as it causes significant spectral contamination. To prevent sample loss, slides can be coated with nitrocellulose to act as an adhesive [25].

- Matrix Application (for MALDI-MSI): A matrix is essential for Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization (MALDI) to facilitate analyte extraction and ionization. The choice of matrix and application method must be optimized.

- Common Matrices:

- 2,5-Dihydroxybenzoic acid (DHB): Often used for metabolites and lipids in positive ion mode.

- α-Cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (CHCA): Preferred for peptides and small proteins in positive ion mode.

- Sinapinic Acid (SA): Suitable for larger proteins.

- Application: Automated sprayers are commonly used to ensure a homogeneous, fine crystalline coating. The matrix crystallizes with analytes extracted from the tissue, a process crucial for ionization [25].

- Common Matrices:

- Inclusion of Internal Standards: For reliable data, especially in quantitative MSI (qMSI), internal standards should be applied. These can be deposited onto the tissue section prior to matrix application or added to the matrix solution itself. This step corrects for variations in ionization efficiency across the sample [25].

Instrumental Workflow and Data Acquisition

- Grid Definition: The user defines an (x, y) grid over the sample surface, determining the spatial resolution (pixel size) of the experiment [25].

- Data Acquisition: The mass spectrometer sequentially acquires a mass spectrum at each pixel within the grid. The resulting data is a hyperspectral cube where each pixel contains a full mass spectrum [25].

- Image Generation: Computational software is used to select a specific mass-to-charge (m/z) value. The intensity of this m/z is extracted from every pixel's spectrum and assembled into a heat map image, visually representing the spatial distribution of that ion [25].

- Molecule Identification: The identity of ions of interest can be determined through:

- Tandem MS (MS/MS): Performing fragmentation experiments to elucidate molecular structure.

- Accurate Mass Matching: Comparing the intact mass to databases of known molecules within a specified mass error tolerance [25].

MSI Experimental Workflow: From sample collection to data analysis.

Troubleshooting Common MSI Challenges

FAQ 1: Why is my signal intensity low or inconsistent across the tissue section?

Potential Cause: Inefficient analyte extraction or cocrystallization with the matrix (in MALDI-MSI), often due to suboptimal sample preparation. Solution:

- Check Matrix Crystallization: Ensure the matrix is applied evenly and has formed a homogeneous, microcrystalline layer. Recrystallize the matrix if necessary.

- Tissue Washes: Perform a quick tissue wash (e.g., with Carnoy's solution for proteins or ammonium citrate for low molecular weight species) to remove salts and lipids that can suppress ionization [25].

- Confirm Matrix Compatibility: Verify that the selected matrix is appropriate for your target analytes (e.g., Sinapinic Acid for proteins, CHCA for peptides).

- Apply an Internal Standard: Normalize signal response across the tissue section by applying a uniform internal standard [25].

FAQ 2: How can I improve the spatial resolution of my MSI experiment?

Potential Cause: The spatial resolution is inherently limited by the ionization technique and instrument parameters. Solution:

- Select the Appropriate Technology: The choice of ionization source dictates the practical resolution limit.

- Optimize Instrument Settings: For MALDI, reduce the laser focus diameter and the step size between measurement points. For SIMS, use a finer primary ion beam [26].

- Consider High-Resolution Techniques: For subcellular resolution (down to 50 nm), NanoSIMS is the preferred method, though it is typically limited to smaller molecules and elemental tags [26].

FAQ 3: My experiment is taking too long, especially for high-resolution scans. How can I increase throughput?

Potential Cause: The serial nature of microprobe-mode MSI creates a trade-off between spatial resolution, sample area, and acquisition time. Solution:

- Utilize Faster Mass Analyzers: Time-of-Flight (TOF) analyzers with high-frequency lasers (e.g., 5-10 kHz) can significantly speed up data acquisition [27].

- Implement Sparse Sampling: Use computational approaches like compressed sensing. By acquiring data from only a fraction of pixels and computationally reconstructing the image, you can reduce acquisition time without substantial loss of image quality [27].

- Explore Microscope Mode: If available, this mode can analyze multiple pixels simultaneously, drastically reducing the number of sampling events required [26] [27].

FAQ 4: How can I move from relative distribution to absolute quantification of my drug compound?

Challenge: MSI signal intensity is influenced by multiple factors beyond concentration, making absolute quantification difficult. Solution for qMSI:

- Apply a Calibration Curve: Spray a uniform series of calibration standards with known concentrations onto control tissue sections alongside your study samples [25].

- Use a Stable Isotope-Labeled Analog: Employ an isotopically labeled version of the drug as a robust internal standard, applied homogeneously to the tissue section. This corrects for ionization suppression and extraction efficiency variations [25].

- Validate with LC-MS/MS: Correlate MSI data with quantitative results from liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry analysis of homogenized tissue punches from adjacent sections [25].

Comparison of Ionization Techniques for MSI

The choice of ionization method is crucial and depends on the required spatial resolution, mass range, and the type of analytes being studied.

| Ionization Source | Type of Ionization | Best For | Spatial Resolution | Practical Mass Range | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SIMS [26] | Hard | Elemental ions, small molecules, lipids | < 1 µm (NanoSIMS: 50 nm) | 0 - 1,000 Da | Highest resolution, but limited to small molecules; can be destructive. |

| MALDI [26] [25] | Soft | Lipids, peptides, proteins, metabolites | ~20 µm (5-10 µm possible) | 0 - 100,000 Da | The dominant technique for biological applications; requires matrix application. |

| DESI [26] | Soft | Small molecules, lipids, drugs | ~50 µm | 0 - 2,000 Da | Ambient technique; minimal sample preparation required. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| DHB Matrix [25] | Matrix for MALDI; facilitates soft ionization of metabolites and lipids. | Often used in positive ion mode. Can form "sweet spots" requiring homogeneous application. |

| CHCA Matrix [25] | Matrix for MALDI; ideal for peptide and small protein analysis. | Provides fine, homogeneous crystals. Preferred for high-spatial resolution work. |

| Sinapinic Acid (SA) Matrix [25] | Matrix for MALDI; suited for larger proteins. | Generates larger crystals, which can limit ultimate spatial resolution. |

| Nitrocellulose Coating [25] | "Glue" to prevent tissue from flaking or washing off slides during preparation. | Critical for fragile tissues or when extensive washing protocols are used. |

| Internal Standards [25] | Enables signal normalization and absolute quantification. | Should be a stable isotope-labeled analog of the target analyte or a structurally similar compound. |

| Carnoy's Solution [25] | Tissue wash to remove interfering salts and lipids for improved protein signal. | Ethanol:chloroform:glacial acetic acid in a 6:3:1 ratio. |

| Ammonium Citrate [25] | Tissue wash to enhance signal for low molecular weight species and drugs. | Helps remove salts that cause ion suppression. |

Within the context of spatial ecology experimentation, MSI provides an unparalleled lens to view the complex interactions between drugs, metabolites, and their biological environment. The future of MSI is being shaped by efforts to overcome its primary challenges: throughput and quantification. Emerging directions include:

- High-Throughput and 3D MSI: Robotic platforms for automated sample loading and advanced data analysis pipelines are making large-scale and 3D MSI studies more feasible, allowing for the reconstruction of entire molecular landscapes in tissues [27].

- Multimodal Imaging: Correlating MSI data with other imaging modalities like histology (H&E staining), immunohistochemistry, or MRI strengthens biological conclusions by overlaying molecular with morphological or structural information [26] [25].

- Single-Cell MSI: Pushing spatial resolution to the single-cell level is a frontier area, promising to uncover cellular heterogeneity in drug uptake and metabolism that is averaged out in bulk analyses [25].

As these technological and computational advances mature, MSI will become an even more indispensable tool, enabling researchers to precisely map the spatial fate of compounds and answer fundamental questions in drug development and spatial ecology.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the most common causes of simulation instability in reaction-diffusion models, and how can they be resolved? Simulation instability in reaction-diffusion models often arises from an inappropriate choice of numerical parameters or an incorrect model formulation. Key factors include:

- Excessive Time Steps or Coarse Spatial Discretization: The discrete time step (Δt) and grid cell size (Δx) must satisfy stability conditions for the explicit numerical methods often used. A finer grid and smaller time step are typically required for higher accuracy and stability [28] [29].

- Incorrect Model Scope for the Observed Phenomenon: A model might be unstable if it does not adequately represent the physical reality. For instance, in catalytic or biofilm systems, a "regular" model may fail for highly active catalysts, where a "dead zone" model with a moving boundary is instead required for a correct and stable solution [30].

- Unaccounted for Spatial Heterogeneities: Real-world ecological gradients, like rainfall, can create significant spatial variations. Models assuming homogeneous parameters may become unstable when applied to these heterogeneous environments, necessitating more complex modeling approaches [2].

FAQ 2: How do I choose between a stochastic and a deterministic simulation framework for my biological system? The choice depends on the scale of your system and the nature of the question you are investigating.

- Use Deterministic Models (e.g., SymPhas): These are suited for systems with large numbers of molecules where average concentrations are meaningful. They are typically defined by partial differential equations (PDEs) and are efficient for simulating large-scale pattern formation, such as Turing patterns [31].

- Use Stochastic Particle-Based Models (e.g., PyRID, MCell, Smoldyn): These are essential when molecular counts are low, when individual particle interactions and random fluctuations are critical to the system's behavior (e.g., gene expression, signaling in cellular microdomains), or when complex geometries and polydispersity (varied particle sizes) are important [32].

FAQ 3: My model produces patterns that are sensitive to initial conditions. Is this an error or a feature? This is often a feature of nonlinear reaction-diffusion systems, not an error. Systems undergoing Turing instabilities can amplify small fluctuations into heterogeneous patterns. The specific shape and position of patterns can be altered by noise or small changes in initial conditions [2]. To ensure reliable pattern formation, mechanisms such as pre-patterning (organized initial conditions) or the inclusion of environmental heterogeneities (e.g., nutrient gradients) can be used to break the symmetry in a specific fashion [2].

FAQ 4: What are the best practices for designing a spatial sampling strategy for ecological field validation? A proper spatial sampling strategy is crucial for collecting high-quality data for model validation.

- Define the Objective: Clearly state whether you are sampling for a spatial mean, to identify treatment effects, or for spatial mapping [33].

- Choose a Sampling Design: Common approaches include:

- Survey Designs: Systematic or random sampling for mapping and estimation.

- Experimental Designs: Incorporating treatments and replication to test hypotheses.

- Adaptive Sampling: Modifying the sampling scheme in real-time based on incoming data, which is useful for tracking rare phenomena [33].

- Incorporate Prior Information: Use existing data, known boundaries, and knowledge of the ecosystem to inform your sampling locations and optimize the strategy [33].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Simulation fails to produce expected Turing patterns.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Incorrect parameter set | Consult a parameter map for your specific model (e.g., Gray-Scott). Check if your (k, F) values lie within a known pattern-forming region [29]. | Systematically vary parameters (feed and kill rates) based on established literature to locate the pattern-forming region. |

| Numerical instability | Reduce the simulation time step (Δt) and/or increase spatial resolution (reduce Δx). | Ensure the simulation satisfies the stability condition for your numerical method. For the Laplacian, use a convolution kernel with appropriate weights (e.g., center -1, adjacent 0.2, diagonals 0.05) [28]. |

| Insufficient simulation time | Patterns like spots or stripes can take many iterations to emerge from a random or small seed. | Run the simulation for more iterations. Monitor the state to ensure it has reached a steady pattern. |

Issue: Discrepancy between model predictions and experimental data in a catalytic reactor or biofilm system.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Unmodeled "dead zone" | Calculate the Thiele modulus for your system. High values indicate that reactants may be consumed before penetrating the entire pellet or biofilm [30]. | Switch from a "regular" boundary value problem to a "dead zone" or free boundary problem where the inner region has zero concentration and an internal boundary condition is applied [30]. |

| Ignored external mass-transfer resistance | Calculate the Biot number (Bim). Low values signify significant external resistance. | Include external mass-transfer resistance in your boundary conditions (e.g., Eq. 2 in [30]). |

| Incorrect error structure in parameter estimation | Perform replicate experiments at different conversion levels to characterize the variance. | Use weighted least squares for parameter estimation, where the weight for each data point is the inverse of its variance, instead of standard least squares [34]. |

Data Presentation

Table 1: Comparison of Modern Reaction-Diffusion Simulation Software

| Software | Primary Language/Method | Key Features | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|

| SymPhas 2.0 [31] | C++, CUDA (GPU) | Compile-time symbolic algebra; automatic functional differentiation; MPI & GPU parallelism. | Large-scale phase-field and reaction-diffusion models requiring high performance. |

| PyRID [32] | Python (with Numba JIT) | Stochastic particle-based; rigid bead models for proteins; surface diffusion on 3D meshes. | Detailed biological systems with complex geometries, polydispersity, and membrane-associated processes. |

| MCell [32] | C++, Monte Carlo | Stochastic reaction-diffusion in realistic 3D cellular geometries; integration with CellBlender. | Synaptic transmission, cellular signaling, and other processes in complex, mesh-based geometries. |

| Smoldyn [32] | C/C++, Python API | Stochastic particle-based; high spatial resolution; anisotropic diffusion. | Confined biochemical environments with nanometer-scale spatial resolution. |

| ReaDDy [32] | C++, Python bindings | Force-based interactions between particles; modeling of molecular crowding and aggregation. | Intracellular organization where explicit particle interactions are critical. |

Table 2: Key Parameters and Their Effects in the Gray-Scott Reaction-Diffusion Model

| Parameter | Typical Symbol | Role in the Model | Effect on System Behavior |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feed Rate | F | Replenishes the "U" chemical substrate; F(1-u) [28] [29]. | Higher F generally promotes homogeneous, U-dominated states. Lower F allows V to consume U and form patterns. |

| Kill Rate | k | Removes the "V" chemical catalyst; -kv [28] [29]. | Higher k inhibits V growth, leading to simpler patterns or extinction. Lower k allows for complex, sustained patterns. |

| Diffusion Rate of U | D_u | Controls how fast the substrate U spreads. | Slower diffusion (relative to D_v) is a key condition for Turing instability and pattern formation. |

| Diffusion Rate of V | D_v | Controls how fast the catalyst V spreads. | Faster diffusion (relative to D_u) helps create the short-range activation and long-range inhibition needed for patterns. |

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Methodology: Experimental Verification of a "Dead Zone" in a Catalyst Pellet [30]

1. Objective: To confirm the existence of a "dead zone" (a region of zero reactant concentration) inside a catalyst pellet under conditions of high reaction rate and diffusion limitation.

2. Materials:

- Reaction System: Hydrogenation of propylene. Reactants: Propylene and hydrogen. Catalyst: Nickel catalyst formed into slab pellets with a large diameter/width ratio.

- Apparatus: Isothermal plug flow reactor, gas supply system, analytical equipment (e.g., GC) to measure outlet conversion.

3. Procedure: 1. Model Formulation: The diffusion-reaction process is described by a nonlinear, second-order ODE (Eq. 1 in [30]) with a power-law kinetic term. 2. Analytical Solution: The boundary value problem is solved analytically for two distinct cases: * Regular Model: For lower Thiele moduli, where the reactant concentration is everywhere greater than zero. Boundary condition: dc/dx = 0 at the pellet center (x=0). * Dead Zone Model: For higher Thiele moduli, where a region of zero concentration exists inside the pellet. This is a free boundary problem with an additional condition: c = 0 and dc/dx = 0 at the dead zone boundary (x = x_dz). 3. Parameter Variation: Conduct experiments over a range of operating conditions (especially temperature, which affects the Thiele modulus) to traverse regions where each model is valid. 4. Data Collection & Comparison: Measure the observed reaction rate or conversion and compare it with the predictions from both the regular and dead zone analytical solutions.

4. Expected Outcome: The experimental data will align with the regular model at lower temperatures (lower Thiele modulus) and with the dead zone model at higher temperatures (higher Thiele modulus), validating the hypothesis that the full description of the process requires both model solutions.

Mandatory Visualization

Diagram 1: Model Selection Workflow for Spatial Dynamics

Diagram 2: Gray-Scott Reaction-Diffusion System Logic

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational and Experimental "Reagents"

| Item | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Gray-Scott Model Parameters (F, k) [28] [29] | Control the feed rate of substrate U and the kill/removal rate of catalyst V. Small adjustments can drastically change emergent patterns. | Generating synthetic patterns for studying biological morphogenesis (e.g., animal coat patterns). |

| GPU-Accelerated PDE Solver [31] | Enables large-scale, high-performance computation of reaction-diffusion systems, reducing simulation time from days to minutes. | Running 3D phase-field simulations for microstructural evolution or large 2D Turing pattern analysis. |

| Spatial Sampling Design [33] | A planned strategy for collecting spatial data from an ecosystem, crucial for model validation and minimizing experimental effort. | Assessing the spatial distribution of soil fauna biodiversity in a grassland ecosystem. |

| Thiele Modulus [30] | A dimensionless number that compares the reaction rate to the diffusion rate. A high value indicates potential for "dead zone" formation. | Diagnosing whether a catalyst pellet or biofilm system requires a "dead zone" model for accurate simulation. |

| Weighted Least Squares Estimation [34] | A parameter estimation technique that weights data points by the inverse of their variance, leading to more precise kinetic parameters. | Precisely estimating kinetic parameters from experimental data where measurement error is not constant. |

Designing Multi-Factorial Experiments to Capture Ecological Realism

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: What is the core challenge of designing multi-factorial experiments? The primary challenge is balancing ecological realism with experimental feasibility. Natural systems are inherently multidimensional, with multi-species assemblages experiencing spatial and temporal variation across numerous environmental factors. The main technical hurdle is avoiding "combinatorial explosion," where the number of unique treatment combinations increases exponentially with each additional environmental factor, quickly becoming logistically unmanageable [35] [1].

FAQ 2: How can I manage "combinatorial explosion" in my experimental design? Instead of testing every possible combination of factors, you can employ strategic designs. Where two primary stressors can be identified, one promising approach is the use of response surface methodologies. These build on classic one-dimensional dose-response curves to explore the interaction effects of two key variables more efficiently than a full factorial design [1].

FAQ 3: Why is it important to move beyond classical model organisms? While model species offer well-developed methodologies, they can be poor proxies for natural communities. Using a wider range of organisms helps reveal how interspecific and intraspecific diversity shapes ecological responses to global change. In aquatic systems, for example, non-model organisms like diatoms, ciliates, and killifish provide unique opportunities to study key biological questions [35] [1].

FAQ 4: How should I incorporate natural environmental variability? Instead of holding conditions constant at an average value, introduce realistic fluctuations. When designing these fluctuations, explicitly consider their magnitude, frequency, and predictability. This approach helps uncover the mechanistic basis for how environmental variability affects ecological dynamics [1].

FAQ 5: What technological advances can aid complex experiments?

Modern experimental ecology can leverage novel technologies such as -Omics approaches, automated data generation and analysis, and remote sensing. These tools can increase the scope, scale, and depth of insights, but must be built upon a foundation of well-thought-out hypotheses and robust experimental design [35] [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Methodologies

Table 1: Experimental Approaches in Aquatic Ecology

| Approach | Scale & Description | Key Utility | Common Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microcosms [35] | Small-scale, highly controlled laboratory systems. | Fundamental for testing theoretical principles (e.g., competitive exclusion, predator-prey dynamics). | Lack of realism; may not capture natural community dynamics. |

| Mesocosms [35] | Intermediate-scale, semi-controlled systems (e.g., in-situ enclosures). | Bridges the gap between lab and field; improves realism for studying evolutionary and community changes. | Limited replication; may not fully capture large-scale processes. |

| Whole-System Manipulations [35] | Large-scale field manipulations (e.g., whole-lake experiments). | Provides key applied insights into anthropogenic effects (e.g., nutrient loading, deforestation). | Logistical difficulty; high cost; limited replication. |

| Resurrection Ecology [35] | Revival of dormant stages from sediment cores. | Provides direct evidence of past evolutionary and ecological changes; powerful when paired with environmental archives. | Largely limited to planktonic taxa with dormant stages. |

Table 2: Strategic Frameworks for Predictive Ecology

| Framework | Methodology | Application |

|---|---|---|

| Integrative Approach [35] | Combines experiments across spatial/temporal scales with long-term monitoring and modeling. | Provides the most robust insights into ecological dynamics under change. |

| Experimental Evolution [35] | Exposes populations to controlled environmental manipulations over multiple generations. | Isolates effects of environmental change and studies capacity for rapid adaptation. |

| Paleolimnological Approaches [35] | Uses sediment cores as natural archives of historical changes. | Informs on past states ("where we were") to help predict future trajectories. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Implementing a Response Surface Design

- Identify Key Stressors: Based on observational data or prior experiments, select the two most influential environmental factors (e.g., Temperature and Nutrient concentration).

- Define Levels: For each factor, define a range of levels (e.g., low, medium, high) that are ecologically relevant.

- Design Matrix: Instead of a full factorial design (3x3=9 combinations), a response surface design (e.g., Central Composite Design) may use a smaller set of treatment combinations strategically placed to model a curved surface.

- Replicate: Ensure sufficient replication at each design point to account for variability.

- Analyze: Use regression models to fit a response surface and identify interaction effects between the stressors.

Protocol 2: Incorporating Environmental Variability

- Parameterize Fluctuations: Use long-term monitoring data to define the magnitude (range of values) and frequency (how often changes occur) of a key environmental variable (e.g., temperature).

- Program Controls: Use automated environmental controllers to apply the defined fluctuation regime to treatment systems.

- Include a Constant Treatment: Run a parallel control treatment where the same environmental variable is held at the mean value.

- Compare Dynamics: Analyze differences in species responses, population stability, or ecosystem function between the fluctuating and constant treatments.

Visualization of Experimental Design Logic

Diagram 1: Strategic framework for overcoming key experimental design challenges.

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for Spatial Ecology Experiments

| Category / Item | Brief Explanation of Function |

|---|---|

| Environmental Chambers/Controllers [1] | Precisely manipulate and program abiotic conditions (e.g., temperature, light) to test specific environmental factors and their variability. |

| Mesocosm Enclosures [35] | Semi-controlled containers (e.g., tanks, sediment cores) that bridge the gap between small-scale lab studies and the full complexity of the natural field environment. |

| -Omics Kits [35] [1] | Reagents for genomics, transcriptomics, etc., to uncover mechanistic responses and genetic diversity within and between populations. |

| Sediment Corers [35] | Equipment to extract layered sediment cores from lakes or oceans, which serve as natural archives for resurrection ecology and paleolimnological studies. |

| Automated Data Loggers [1] | Sensors that continuously monitor environmental parameters (e.g., pH, dissolved oxygen, temperature), providing high-resolution data for correlating with biological responses. |

| Stable Isotope Tracers | Chemical compounds used to track nutrient flow and trophic interactions within experimental communities, illuminating food web dynamics. |

| Data Analysis Pipelines [2] | Computational tools and scripts (e.g., in R or Python) essential for analyzing complex, multidimensional data from factorial experiments. |

Solving Practical Problems: Strategies for Robust and Reproducible Spatial Experiments

Overcoming Data Harmonization and Standardization Hurdles

In the rapidly evolving field of spatial ecology and biomedical research, data harmonization—the process of standardizing and integrating diverse datasets into a consistent, interoperable format—has emerged as both a critical necessity and a significant challenge. As research becomes increasingly data-driven, harmonization ensures that data generated from disparate tools and platforms can be effectively integrated to derive meaningful insights [36]. For spatial ecology experimentation specifically, successfully harmonizing datasets generated by different technologies and research groups requires an extensive supportive framework built by all members involved [37].

The stakes are particularly high in spatial research, where harmonized data is crucial for enabling reproducibility, collaboration, and AI-driven insights. Poorly harmonized data can lead to inefficiencies, increased costs, and missed opportunities for breakthroughs in both ecological monitoring and drug development [36]. This technical support center provides actionable troubleshooting guidance and standardized protocols to help researchers overcome the most pressing data harmonization challenges in their spatial experimentation workflows.

Common Data Harmonization Challenges

Spatial researchers frequently encounter several consistent hurdles when attempting to harmonize data across experiments, platforms, and research teams. The table below summarizes these key challenges and their impacts on research outcomes.

Table 1: Common Data Harmonization Challenges in Spatial Research

| Challenge Category | Specific Issues | Impact on Research |

|---|---|---|

| Data Heterogeneity | Diverse formats from genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and clinical data [36] | Complicates integration and standardization efforts; creates data silos |

| Metadata Inconsistencies | Missing metadata, incomplete annotations, inconsistent variables [36] | Impedes integration; delays research timelines for validation and curation |

| Spatial Complexity | Varying scales, resolutions, and coordinate reference systems [2] | Hinders cross-study spatial comparisons and meta-analyses |

| Technological Fragmentation | Isolated datasets across departments, platforms, or repositories [36] | Creates barriers to collaboration and knowledge sharing |

| Volume and Scalability | Large datasets (often tens of terabytes) from modern spatial technologies [36] | Challenges storage, processing, and analysis capabilities |

Troubleshooting Guide: Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: How can we effectively integrate spatial multi-omics data from different analytical platforms?

Problem: Researchers often struggle with combining spatial transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics data generated from different instrumentation platforms, leading to fragmented biological insights.

Solution:

- Adopt Common Data Elements (CDEs): Establish and implement CDEs across all research teams to ensure consistent data collection [37]. CDEs are standardized questions with specified sets of responses that can be used across different studies.

- Implement Spatial Metadata Standards: Apply minimum information standards such as the 3D Microscopy Metadata Standards (3D-MMS), which includes 91 fields for standardizing metadata for three-dimensional spatial datasets [37].

- Utilize Common Coordinate Frameworks (CCFs): Develop and adopt formal semantics and CCFs to ensure spatial data can be combined computationally with minimal human intervention [37].

- Leverage Harmonization Platforms: Employ specialized platforms like Polly, which uses machine learning algorithms to ensure uniformity across data formats, structures, and semantics, preparing datasets for downstream analysis [36].

Q2: What strategies can overcome metadata incompleteness in long-term spatial ecology studies?

Problem: Historical and ongoing spatial ecology datasets often suffer from inconsistent or missing metadata, making integration and replication difficult.

Solution:

- Create Metadata Annotation Protocols: Establish rigorous metadata annotation procedures with both dataset-level (10-15 fields) and sample-level (15-20 fields) specifications [36].

- Implement QA/QC Checks: Integrate approximately 50 quality assurance/quality control checks throughout data generation and processing pipelines to ensure data quality and completeness [36].

- Adopt Essential Biodiversity Variables (EBVs): For ecological studies, utilize the EBV framework as a common, interoperable approach for data collection and reporting [38].

- Apply FAIR Principles: Ensure data is Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable by providing detailed methodological information, using unique identifiers, and implementing structured metadata [37].

Q3: How can we maintain data harmonization when scaling from experimental to natural systems in spatial ecology?

Problem: Translating findings from controlled experiments to complex natural systems introduces significant data integration challenges due to differing scales and environmental variability.

Solution:

- Implement Multi-Scale Frameworks: Combine experiments at various spatial and temporal scales with long-term monitoring and modeling [35].

- Utilize Spatiotemporal Models: Apply emerging statistical models like Vector Autoregressive Spatiotemporal (VAST) models that can analyze survey data from multiple sources and provide estimates of population density over space and time [39].