Movement Ecology: From Foundational Principles to Predictive Science in a Changing World

This article synthesizes the core principles and advancing methodologies of movement ecology, a field fundamental to understanding biodiversity patterns, ecosystem processes, and species survival.

Movement Ecology: From Foundational Principles to Predictive Science in a Changing World

Abstract

This article synthesizes the core principles and advancing methodologies of movement ecology, a field fundamental to understanding biodiversity patterns, ecosystem processes, and species survival. Tailored for researchers and scientists, we explore the integrative Movement Ecology Framework (MEF), detailing the interplay of internal state, navigation, motion capacity, and external factors. We cover cutting-edge technological and analytical tools—from biologging and hidden Markov models to movement forecasting—that are transforming data collection and interpretation. The content addresses critical challenges in data integration and prediction under global change, while highlighting validation techniques and cross-disciplinary applications that enhance the robustness and applicability of movement research for effective conservation and policy.

The Core Principles of Movement Ecology: An Integrative Framework for Understanding Organismal Movement

Defining Movement Ecology and Its Central Role in Shaping Biodiversity

Movement ecology is an interdisciplinary scientific field dedicated to understanding the causes, mechanisms, patterns, and consequences of organism movement. It serves as a crucial component of nearly every ecological and evolutionary process, fundamentally influencing major environmental challenges including habitat fragmentation, climate change, biological invasions, and the spread of pests and diseases [1]. The field has coalesced around a unifying movement ecology framework developed to integrate specialized approaches that were previously fragmented across taxonomic groups and research paradigms [1]. This framework positions movement itself as the central theme, aiming to foster a general theory of organism movement that transcends traditional boundaries between species and movement types. The capacity of organisms to move determines their ability to access resources, find mates, escape predators, and respond to environmental changes, thereby directly shaping the distribution, persistence, and diversity of life on Earth [1]. This whitepaper examines the core principles of movement ecology and establishes its fundamental role in generating and maintaining biodiversity patterns across landscapes.

The Conceptual Framework of Movement Ecology

The movement ecology paradigm, as formalized by Nathan et al. (2008), provides a coherent conceptual structure for analyzing organism movement [1]. This framework asserts that four basic components interact to determine movement paths:

- Internal State: The physiological and neurological condition of an individual organism that affects its motivation and readiness to move (e.g., hunger, hormonal state).

- Motion Capacity: The suite of biomechanical and morphological traits that enables movement execution (e.g., wings, legs, seeds).

- Navigation Capacity: The sensory and cognitive mechanisms that enable orientation in space and time (e.g., memory, sensory detection, cognitive maps).

- External Factors: Biotic and abiotic environmental elements that influence movement (e.g., resources, predators, physical barriers, weather) [1].

These components interact through three key processes: the motion process (realized movement capacity), the navigation process (realized orientation capacity), and the movement propagation process (the resulting movement path) [1]. The framework also features a nested design applicable to passively dispersed organisms like plants, where the dispersal vector (e.g., fruit bat) becomes the focal individual in an outer loop, while the dispersed seed (the focal individual in the inner loop) is affected by the vector as an external factor [1]. This comprehensive framework enables researchers to systematically dissect movement phenomena across diverse taxa, from microorganisms to plants and animals.

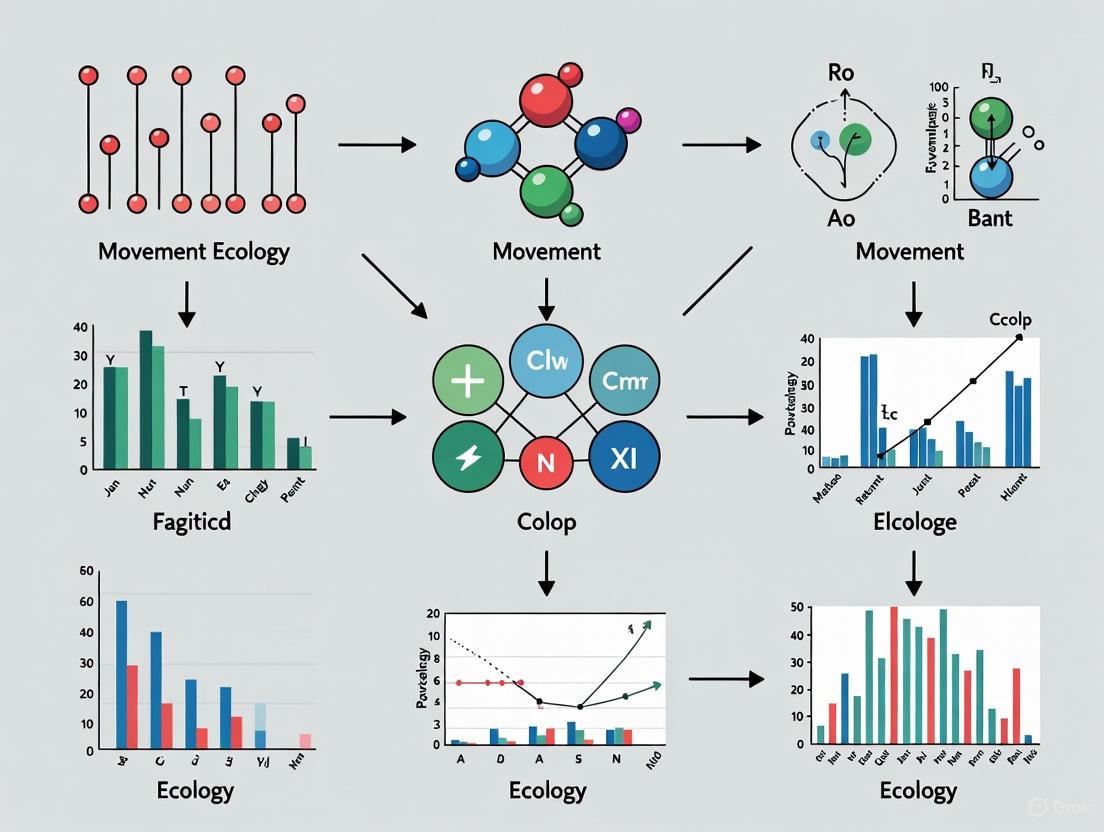

Figure 1: The Movement Ecology Framework illustrating the interactions between its four core components and the resulting movement path. Adapted from Nathan et al. (2008) [1].

Quantitative Approaches to Measuring Movement

The quantitative analysis of movement employs sophisticated mathematical models and statistical techniques to characterize movement patterns and connect them to ecological processes. Movement Ecology, the leading journal in the field, publishes novel insights from both empirical and theoretical approaches, with current impact metrics indicating its growing influence (Journal Impact Factor: 3.9; 5-year Journal Impact Factor: 4.5) [2]. The journal showcases research addressing diverse movement phenomena including foraging, dispersal, and seasonal migration across all taxa [2].

Analytical Frameworks and Movement Metrics

Quantitative movement analysis draws from mathematical ecology, employing various models to characterize movement data [3]. A prominent approach involves fitting Lévy distribution models to movement data and identifying power laws that may indicate optimized search strategies in certain ecological contexts [3]. Other correlated random walk models help quantify spatial patterns of animal movement, enabling researchers to connect individual movement tracks to broader population distribution patterns [3]. These quantitative approaches allow for the mathematical description of movement patterns, such as analyzing how human hunter-gatherer groups move between resource patches or how marine predators optimize foraging efficiency [3].

Table 1: Key Quantitative Metrics in Movement Ecology Research

| Metric Category | Specific Metrics | Ecological Application | Analytical Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Movement Path Characteristics | Step length, Turning angles, Movement rate | Foraging efficiency, Search strategy identification | Lévy flight analysis, Correlated random walks [3] |

| Space Use Patterns | Home range size, Utilization distribution, Site fidelity | Habitat selection, Territorial behavior, Resource use | Kernel density estimation, First-passage time analysis [4] |

| Dispersal Metrics | Dispersal distance, Migration rate, Path straightness | Metapopulation dynamics, Gene flow, Range shifts | Capture-recapture models, Genetic assignment tests [5] |

| Population Redistribution | Diffusion coefficients, Advection rates, Population spread | Invasion biology, Climate change responses, Conservation planning | Reaction-diffusion models, Individual-based simulations [5] |

Experimental Protocols for Movement Tracking

Modern movement ecology relies on advanced technologies for data collection. The following protocol outlines a standardized approach for movement tracking studies:

Protocol 1: Animal-Borne Bio-Logging for Movement Analysis

Instrument Selection: Choose appropriate bio-logging devices (e.g., GPS tags, accelerometers, environmental sensors) based on organism size, study objectives, and deployment duration. Modern tags can record location, activity, physiology, and environmental context simultaneously [2].

Sensor Calibration: Calbrate all sensors before deployment. For GPS tags, determine fix acquisition rate and accuracy. For accelerometers, establish behavior-specific signatures through controlled observations or captive trials [2].

Animal Capture and Handling: Use species-appropriate capture methods that minimize stress and handling time. Follow ethical guidelines for animal welfare during capture and instrument attachment.

Device Attachment: Employ species-specific attachment methods (e.g., harnesses, collars, adhesives, direct attachment) that minimize impact on natural behavior while ensuring instrument retention for study duration.

Data Collection: Program devices according to research questions, balancing sampling frequency with battery life. For GPS studies, typical sampling rates range from seconds for fine-scale movements to hours for migratory studies [2].

Data Retrieval and Processing: Recover data via remote download or device recovery. Process raw data to correct errors, filter outliers, and calculate derived movement metrics (e.g., step lengths, turning angles, displacement distances) [3].

Environmental Data Annotation: Link movement tracks with environmental data using systems like the Environmental-Data Automated Track Annotation (Env-DATA), which connects animal locations with environmental variables such as weather, topography, and land cover [4].

Statistical Modeling: Apply appropriate movement models (e.g., state-space models, step selection functions) to infer behavioral states, identify drivers of movement, and quantify habitat selection [4].

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for bio-logging studies in movement ecology, from instrument selection to statistical analysis.

Movement Ecology's Role in Biodiversity Dynamics

Movement ecology provides critical insights into spatiotemporal biodiversity dynamics by linking individual movements to population, community, and ecosystem-level patterns.

Genetic and Population-Level Consequences

Animal movement directly enables gene flow between populations, maintaining genetic diversity and reducing inbreeding depression in isolated subpopulations [5]. The quantitative analysis of movement patterns reveals how different dispersal strategies affect metapopulation dynamics, where the persistence of species in fragmented landscapes depends on movement between habitat patches [5]. Turchin's foundational work demonstrates how modeling population redistribution through movement parameters helps predict species persistence under changing environmental conditions [5]. The integration of movement data with landscape genetics has further elucidated how movement barriers and corridors shape genetic structure across populations.

Community and Ecosystem Implications

At the community level, movement processes determine species co-existence and trophic interactions. For instance, the spatial scale of predator movements relative to their prey can stabilize or destabilize population dynamics, while pollinator movement patterns directly affect plant reproductive success and community composition [1]. Recent research highlights that integrating movement ecology with biodiversity research opens new avenues for understanding how cross-scale mechanisms (from individual movements to range shifts) drive biodiversity change [4]. The emerging recognition that movement ecology provides the mechanistic link between environmental heterogeneity and biodiversity patterns has positioned it as a central discipline in conservation science.

Table 2: Movement-Generated Biodiversity Patterns and Conservation Applications

| Biodiversity Pattern | Movement-Generating Mechanism | Conservation Application |

|---|---|---|

| Species Distribution Patterns | Habitat selection during foraging, dispersal limitation, migratory corridors | Protected area design, Wildlife corridors [1] |

| Metapopulation Persistence | Inter-patch dispersal rates, Colonization- extinction dynamics | Habitat network planning, Managing connectivity [5] |

| Trophic Interactions | Predator-prey space use overlap, Pollinator foraging circuits | Ecosystem-based management, Pollinator habitat support [4] |

| Range Shifts | Natal dispersal, Exploratory movements, Conspecific attraction | Climate change adaptation, Assisted migration planning [5] |

| Invasion Dynamics | Jump dispersal, Diffusion, Human-mediated transport | Biosecurity, Early detection systems [5] |

Research Reagent Solutions for Movement Ecology

The experimental study of movement requires specialized tools and technologies. Below is a comprehensive table of essential research reagents and equipment used in modern movement ecology studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Technologies in Movement Ecology

| Research Tool Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bio-Logging Devices | GPS tags, Accelerometers, Geolocators, Time-depth recorders | Recording animal location, activity, and physiology | Fine-scale movement analysis, Energetics studies, Migration tracking [2] |

| Remote Sensing Platforms | Satellite imagery, UAVs (drones), Automated radio telemetry | Landscape monitoring, Animal detection from distance | Habitat mapping, Population surveys, Movement corridor identification [2] |

| Genetic Analysis Tools | Microsatellite markers, SNP genotyping, Environmental DNA | Individual identification, Relatedness analysis, Diet analysis | Dispersal quantification, Population connectivity, Trophic interactions [5] |

| Environmental Sensors | Weather stations, Soil probes, Oceanographic buoys | Measuring abiotic conditions | Contextualizing movement decisions, Habitat selection studies [2] |

| Analytical Software | R packages (adehabitat, move), ArcGIS, ENV-DATA system | Path segmentation, Home range estimation, Resource selection | Movement statistical analysis, Spatial modeling, Data management [4] |

Movement ecology provides an indispensable framework for understanding and predicting biodiversity patterns in a rapidly changing world. By unifying the study of organism movement across taxa and spatial scales, the field offers mechanistic insights into how individual movement decisions scale up to population distributions, species interactions, and ecosystem functioning. The ongoing development of sophisticated tracking technologies, analytical methods, and theoretical models continues to enhance our capacity to quantify movement processes and their ecological consequences [2]. As global change accelerates, the principles of movement ecology will become increasingly critical for conserving biodiversity, managing ecosystems, and forecasting ecological responses to anthropogenic impacts. The integration of movement ecology into mainstream ecological research represents not merely a specialized subfield, but a fundamental reframing of how we understand the dynamic nature of life on Earth.

The Movement Ecology Framework (MEF) is an integrative paradigm formulated to unify the study of organismal movement across different taxonomic groups and movement types. Proposed by Nathan et al. in 2008, the MEF aims to develop a cohesive theory for understanding the causes, mechanisms, patterns, and consequences of all movement phenomena [1]. Prior to its introduction, movement research was characterized by specialized approaches divided across different "paradigms"—random, biomechanical, cognitive, and optimality—as well as by movement types and taxonomic groups. This specialization often led to fragmented knowledge and reinvention of methodologies [1]. The MEF addresses this by placing movement itself as the central theme and proposing a conceptual structure that links the fundamental components of movement: the internal state, motion capacity, and navigation capacity of an individual, and the external factors that affect its movement [6] [1] [7]. This framework is applicable not only to sentient animals but has also been adapted for passively transported organisms, such as plants, often requiring a nested design to account for the movement of dispersal vectors [1].

Core Components of the MEF

The MEF asserts that four basic components interact to describe the mechanisms underlying movement paths. The following diagram illustrates the relationships and processes linking these components.

Internal State: Why Move?

The internal state refers to the physiological and neurological condition of an individual that affects its motivation and readiness to move [1]. It encapsulates the "why" of movement, representing the internal drivers such as hunger, fear, or reproductive urges that prompt an animal to change its location [6]. For example, hunger may drive a fruit bat to search for food, thus initiating a movement sequence [1]. In a nested application of the MEF to plant dispersal, the internal state of a seed can be described as the evolutionary advantages of dispersal, such as escaping the vicinity of the mother plant [1].

Motion Capacity: How to Move?

Motion capacity is the set of morphological and biomechanical traits that enables an individual to execute movement [1]. This component answers the "how" of movement, representing the organism's fundamental ability to move, whether through walking, flying, swimming, or being passively transported [6] [1]. For a seed dispersed by a fruit bat, its motion capacity is derived from its retention time in the bat’s digestive tract and the bat's own movement [1]. Motion capacity interfaces with external factors; for instance, an animal's locomotion biomechanics interact with substrate characteristics, potentially leading to routine movement along paths that minimize energy expenditure [8].

Navigation Capacity: Where to Move?

Navigation capacity comprises the sensory and cognitive traits that enable an individual to orient its movement in space and time [1]. It addresses the "where to" of movement, involving mechanisms like perception, learning, and memory [6]. Navigation can range from simple taxis (movement in response to a stimulus) to complex cognitive processes like response learning (forming habitual sequences based on cues) and place learning (understanding spatial relationships to form a "cognitive map") [8]. The interplay between navigation capacity and external factors is critical; an individual may use environmental cues or remembered information to guide its path [8].

External Factors

External factors encompass all biotic and abiotic environmental elements that affect an individual's movement, such as resource distribution, predators, terrain, and weather [1]. These factors can directly influence the motion and navigation processes. For example, a narrow strip of forest through an urban area can constrain movement, functioning as a corridor and leading to highly predictable, route-like movement patterns [8].

Quantitative Trends and Technological Tools in Movement Ecology

The field of movement ecology has experienced a technological revolution since the MEF's introduction, leading to an exponential increase in data and analytical capabilities [6] [7].

Trends in Publication and Research Focus

A text-mining analysis of over 8,000 papers from 2009 to 2018 reveals that the publication rate in movement ecology increased considerably during this period [6] [7]. However, research efforts have not been balanced across the MEF components. The majority of studies focus on the effects of external factors on movement, while motion and navigation capacity continue to receive comparatively little attention [6] [7].

Table 1: Analysis of movement ecology literature (2009-2018)

| Aspect | Trend/Finding | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Publication Rate | Considerable increase | Analysis based on >8,000 papers [6]. |

| Primary Research Focus | Effect of environmental factors (external factors) | Motion and navigation capacities are less studied [6]. |

| Common Taxa | Marine and terrestrial realms; applications and methods across taxa | Identified via word patterns in abstracts [6]. |

| Prevalent Software | R software environment | Used by a majority of studies for statistical computing [6]. |

Key Tracking Technologies and Analytical Tools

The "golden era of biologging" has provided researchers with a powerful toolkit to collect high-resolution data on animal movement [6].

Table 2: Key research tools and technologies in movement ecology

| Tool or Technology | Primary Function | Key Application in MEF |

|---|---|---|

| GPS Devices | Precise location tracking | Recording spatio-temporal paths to analyze patterns against external factors [6]. |

| Accelerometers | Measuring fine-scale activity and behavior | Inferring internal state (e.g., foraging, resting) and energy expenditure [6]. |

| Argos & VHF Telemetry | Remote tracking of animal location | Long-term movement tracking, particularly for large-scale migrations [6]. |

| Geolocators (GLS) | Light-based location estimation | Tracking long-distance movements of smaller animals [6]. |

| R Software Environment | Statistical computing and graphics | Data analysis, movement path analysis, and statistical modeling of tracking data [6]. |

Experimental Protocols for Studying MEF Components

A critical application of the MEF is designing experiments to dissect the contributions of its core components to observed movement patterns.

Protocol 1: Identifying Patterns of Route-Use and Inferring Navigation Capacity

Objective: To quantitatively identify habitual routes and distinguish the processes (external constraints vs. cognitive navigation) underlying their formation [8].

- Data Collection: Deploy high-resolution GPS loggers on study animals. The sampling rate should be sufficiently high to capture the fine-scale structure of movement paths (e.g., every few seconds or minutes) [8].

- Path Segmentation and Overlay: For each individual, extract all movement trajectories connecting two recurrent target destinations (e.g., a sleeping site and a major foraging area). Spatially overlay these path segments.

- Quantifying Route Fidelity: Calculate the degree of spatial congruence between the overlaid paths. This can be done by:

- Dividing the area into a grid and measuring the frequency of space use per cell.

- Using a method to quantify the average pairwise distance between all trajectories in the segment [8].

- Identifying High-Fidelity Routes: Apply a threshold to define "routes" as areas exhibiting sequential behavior with low directional variability and high path reuse fidelity [8].

- Linking to Navigation Capacity: Analyze the environmental context of the identified routes.

- If routes consistently occur in areas with strong external constraints (e.g., a narrow corridor between impassable terrain), the movement may be primarily explained by motion capacity interfacing with the environment.

- If routes traverse a homogeneous, unconstrained landscape, it provides stronger evidence for the use of cognitive navigation mechanisms, such as response learning or a cognitive map [8].

Protocol 2: Disentangling Internal State from External Factors

Objective: To determine how an animal's internal state and external environmental conditions interact to shape movement decisions.

- Biologging Sensor Deployment: Equip study animals with a multi-sensor biologging package, including:

- GPS Logger: To record movement paths.

- Accelerometer: To classify behavior (e.g., foraging, running, resting) and serve as a proxy for internal state [6].

- Physiological Sensors (optional): Such as heart rate monitors or body temperature loggers, for direct measurement of physiological internal state.

- Environmental Data Collection: Collect spatially explicit data on relevant external factors, such as:

- Resource availability (e.g., vegetation indices from satellite imagery).

- Predation risk (e.g., derived from landscape openness or known predator locations).

- Abiotic conditions (e.g., temperature, rainfall) [6].

- Integrated Statistical Modeling: Use a modeling framework (e.g., step selection functions or state-space models) within the R environment to analyze the data. The model should test:

- How the probability of movement or direction is influenced by external factors.

- How these relationships are modulated by the internal state inferred from accelerometry or physiological data [6].

A Nested Framework: Application to Plant Dispersal

The MEF is highly adaptable and can be applied to non-motile organisms through a nested design. The following diagram illustrates this application for an animal-dispersed plant.

In this nested framework:

- The outer loop focuses on the dispersal vector (e.g., a fruit bat) as the focal individual, with its movement path shaped by its own internal state, motion capacity, navigation capacity, and external factors [1].

- The inner loop focuses on the seed, where the animal vector becomes a major external factor affecting the seed's movement. The seed's motion capacity is derived from traits like retention time in the vector's gut, and its internal state is the evolutionary advantage of dispersal [1].

- The ultimate seed dispersal path is a product of the interplay between the movement ecologies of the plant and its vector [1].

Movement ecology is founded on the principle that organismal movement is a fundamental mechanism shaping biodiversity patterns, from genetic and individual levels to species and ecosystem levels [9]. The translation of environmental cues into movement decisions is a central process, determined by an individual's internal state and balanced against the costs and benefits of movement [10]. Within this paradigm, three movement types—foraging, dispersal, and migration—represent the most common functional classes of organismal movement. These types are primarily distinguished by their spatiotemporal scales, their immediate causes, and their consequences for individuals and populations [9]. Understanding these movement types is critical for a mechanistic understanding of ecological and evolutionary dynamics, as well as for informing conservation strategies in a rapidly changing world [9] [10]. This technical guide synthesizes core principles, experimental methodologies, and research tools central to the study of these key movement types within the broader context of movement ecology's fundamental principles and processes.

Movement Type Classifications and Characteristics

Animal movements are the primary behavioural adaptation to spatiotemporal heterogeneity in resource availability [11]. The proposed theory states that the length and frequency of animal movements are determined by the interaction between temporal autocorrelation in resource availability and spatial autocorrelation in changes in resource availability [11]. The table below summarizes the defining characteristics of the three key movement types.

Table 1: Comparative summary of key movement types across spatiotemporal scales and ecological functions.

| Characteristic | Foraging | Dispersal | Migration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Resource acquisition for survival and daily energy needs [9] | Gene flow, avoidance of kin competition and inbreeding, bet-hedging [9] [12] | Seasonal tracking of optimal environmental conditions and resources [13] |

| Spatial Scale | Typically within a home range [9] | From natal site to new breeding site or between populations [9] | Often long-distance, between distinct geographic regions (e.g., breeding vs. wintering grounds) [9] [13] |

| Temporal Scale & Frequency | Frequent (e.g., several times per day); occurs throughout the year [9] | Often a one-way, life-stage dependent event (e.g., juvenile); occurs at greater intervals [9] | Regular, recurring (e.g., annual/bi-annual); highly seasonal and predictable [9] [13] |

| Impact on Biodiversity | Affects plant communities through grazing, seed dispersal patterns, and nutrient concentration [9] | Shapes genetic structure of populations, links populations via gene flow and nutrient subsidies [9] | Provides "mobile links" between ecosystems, redistributing nutrients and energy over vast distances [9] [13] |

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual relationship between these movement types and their drivers across spatiotemporal scales, integrating the internal state of the organism with external environmental factors.

Physiological and Environmental Drivers of Movement

The translation of environmental cues into movement decisions is fundamentally determined by an individual's internal physiological state [10]. General body condition, metabolic rates, and hormonal physiology mechanistically underpin this internal state, creating a direct link between physiology and movement ecology.

The Role of Body Condition

Body condition is a key driver of movement across different spatiotemporal scales [10]. A high body condition generally facilitates the efficiency of routine foraging, dispersal, and migration. However, the relationship between condition and the propensity to move is complex and varies by movement type. For foraging, better condition often increases movement efficiency, though parasites or illness can degrade performance [10]. For dispersal, the decision-making is context-dependent; in some species, better body condition is associated with longer dispersal distances, while in others, decreased individual condition stimulates dispersal [10]. For migration, individuals in better body condition at the start of migration often migrate faster and more directionally, while those in lower condition spend more time on stopover activities for refuelling [10].

Hormonal and Molecular Regulation

Body-condition-dependent strategies can be overridden by hormonal changes in response to stressors [10]. In both vertebrates and insects, movement is frequently associated with changes in hormone levels, often in interaction with factors related to body or social condition. The underlying molecular and physiological mechanisms, studied in model species, point to a central role of energy metabolism during glycolysis and its coupling with timing processes, particularly during migration [10]. These physiological feedbacks are crucial for a mechanistic understanding of how movement impacts ecological dynamics across all levels of biological organization.

Early-Life Environmental Carry-Over Effects

Movement syndromes can be shaped by phenotypic plasticity in response to early-life environmental conditions, generating time-delayed carry-over effects [12]. For example, in the Large white butterfly (Pieris brassicae), larval rearing density and diet quality induced significant immediate plasticity in caterpillar physiology and behavior. These larval conditions also produced carry-over effects impacting adult emergence and traits involved in dispersal, demonstrating that the correlations among adult traits (the dispersal syndrome) themselves depended on the larval environment [12]. This highlights the importance of an individual's developmental history in shaping its future movement propensity and capacity.

Methodologies for Movement Ecology Research

Experimental Protocols for Dispersal Syndrome Analysis

Research on how early-life conditions affect adult dispersal traits requires carefully controlled experiments. The following protocol, adapted from a study on Pieris brassicae, provides a template for investigating these carry-over effects [12].

Table 2: Key reagents and materials for studying movement ecology.

| Research Reagent / Material | Primary Function in Movement Ecology Research |

|---|---|

| GPS Telemetry Tags | High-resolution tracking of individual movement paths and space use over time [11]. |

| Passive Acoustic Monitoring (PAM) Hydrophones | Detection of vocal species (e.g., baleen whales) for long-term monitoring of presence, behavior, and song, which can indicate foraging conditions [14]. |

| Stable Isotope Analysis | Investigation of trophic ecology and dietary shifts by analyzing ratios of isotopes (e.g., Carbon-13, Nitrogen-15) in animal tissues [14]. |

| Biometric Measurement Tools | Assessment of individual body condition, a key physiological driver of movement decisions [10]. |

| Controlled Environment Chambers | Manipulation of environmental conditions (e.g., temperature, photoperiod) to test for plasticity and carry-over effects on movement traits [12]. |

Protocol Title: Investigating Larval Environmental Carry-Over Effects on Adult Dispersal Syndromes.

Objective: To quantify the immediate and delayed (carry-over) effects of larval density and diet quality on larval traits, adult emergence, and adult dispersal-related morphology and behavior.

Experimental Design:

- Full-Factorial Design: Employ a fully crossed design with multiple levels of larval density (e.g., four levels) and diet type (e.g., three types) [12].

- Family Structure: Incorporate individuals from multiple families (e.g., eight) to account for and quantify genetic variation [12].

- Replication: Ensure adequate replication within each treatment combination (density x diet x family) for robust statistical power.

Procedural Steps:

- Larval Rearing & Immediate Data Collection: Rear caterpillars in their designated density and diet treatments. Record immediate physiological and behavioral plasticity data, which may include:

- Development time from hatching to pupation.

- Growth rate and final larval mass.

- Survival rate at each life stage.

- Pupal Collection & Monitoring: Collect and weigh pupae. Monitor for successful emergence.

- Adult Trait Measurement: Upon adult emergence, measure traits implicated in dispersal, which may include:

- Morphology: Body mass, wing morphology (e.g., wing length, area, thorax ratio).

- Behavior: Assess mobility and flight propensity using standardized assays (e.g., flight mills, open-field tests).

- Data Analysis:

- Use Linear Mixed Models (LMMs) to analyze the effects of fixed factors (density, diet) and random factors (family) on larval and adult traits [12].

- Analyze correlation structures (dispersal syndromes) among adult traits and test whether these correlations depend on the larval environment.

Passive Acoustic Monitoring for Foraging Ecology

Passive Acoustic Monitoring (PAM) is a powerful remote sensing tool for studying the movement and behavior of vocally active species, particularly in marine environments.

Objective: To use PAM to monitor baleen whale song occurrence as an indicator of species presence, migration timing, and potentially, foraging ecology in a dynamic marine ecosystem [14].

Methodological Workflow:

- Data Acquisition: Deploy hydrophones on fixed or mobile platforms (e.g., cabled observatories, autonomous gliders). Collect continuous or scheduled audio data over extended periods (years) [14].

- Song Detection and Classification: Process acoustic data using automated or manual detection algorithms to identify species-specific song sequences (e.g., for blue, fin, and humpback whales) [14].

- Quantification of Song Presence: Calculate daily and monthly song occurrence or prevalence for each species.

- Linking Song to Environmental and Biological Variables:

- Environmental Data: Collate concurrent data on wind (to assess potential masking noise), sea surface temperature, and upwelling indices (e.g., Biologically Effective Upwelling Transport Index - BEUTI) [14].

- Forage Species Data: Collect data on the abundance and composition of key prey species (e.g., krill, forage fish) through net tows and acoustic backscatter surveys [14].

- Population Data: Utilize long-term photo-identification catalogs to track individual whale presence and estimate local abundance [14].

- Statistical Modeling: Use Generalized Linear Models (GLMs) or similar frameworks to relate interannual variations in song detection to changes in forage species availability, oceanographic conditions, and local whale abundance, while controlling for potential detection biases [14].

The workflow for this integrative approach is depicted below, showing how raw acoustic data is transformed into ecological insights about foraging.

Scaling from Individual Movement to Ecological Consequences

A core challenge in movement ecology is scaling up from the movement paths of individuals to predict broader ecological patterns. The movement of organisms is one of the key mechanisms shaping biodiversity, affecting the distribution of genes, individuals, and species in space and time [9].

Mobile Links and Ecosystem Connectivity

Organismal movements provide 'mobile links' between habitats or ecosystems, thereby connecting resources, genes, and processes among otherwise separate locations [9]. The mode of movement determines the nature of this link:

- Foraging movements can concentrate nutrients (e.g., via latrines) and create heterogeneous grazing patterns that influence plant community composition [9].

- Dispersal directly facilitates gene flow, which can decrease genetic differentiation among populations but also impose a migration load that may disrupt local adaptation [9]. Dispersal also links populations by impacting their synchronicity, which affects meta-population persistence [9].

- Migration can form enormous pulses of biomass that subsidize consumer populations (e.g., Arctic foxes subsidized by snow goose eggs) or lead to catastrophic ecosystem changes through intense, pulsed herbivory [9].

A Unified Theory: Movement Scales Match Environmental Patterns

A proposed unifying theory suggests that the scales of animal movements are driven by the scales of changes in the net profitability of trophic resources, after accounting for movement costs [11]. Evidence from moose (Alces alces) shows that:

- Frequent, small-scale movements are triggered by fast, small-scale "ripples" of change in resource availability (e.g., daily fluctuations in forage quality).

- Infrequent, larger-scale movements (including migration) match slow, large-scale "waves" of change in resource availability (e.g., seasonal phenology of plant growth) [11].

This theory provides a predictive framework for understanding how animals ride waves and ripples of environmental change, and how their movement scales may shift in response to anthropogenic alterations of the environment.

Linking Individual Movement to Population Dynamics and Ecosystem Processes

The Movement Ecology Framework (MEF), introduced by Nathan et al. in 2008, provides an integrative theory for understanding the causes, mechanisms, patterns, and consequences of organismal movement [6]. This framework centers on the interplay between an individual's internal state (why move?), motion capacity (how to move?), and navigation capacity (where to move?), all of which are influenced by external factors (environmental context) [15] [6]. The resulting movement paths feed back into both the internal state of individuals and the external environment, creating a dynamic system [9].

Understanding individual movement is fundamental to ecology because it shapes population dynamics, biodiversity patterns, and ecosystem structure across spatial and temporal scales [6] [9]. Movement affects the distribution of genes, individuals, and species, and mediates critical ecological processes such as nutrient transfer, seed dispersal, and disease dynamics [9]. This technical guide explores the mechanistic links between individual movement behavior and broader ecological patterns, providing researchers with the conceptual foundations and methodological tools needed to investigate these connections.

Theoretical Foundations: From Individuals to Ecosystems

The Movement Ecology Framework

The MEF offers a unified structure for studying movement by breaking down the process into core components [15] [6] [9]:

- Internal State: The physiological and psychological drivers that motivate movement, such as finding food, mates, or avoiding predators. In the Iberian lynx, for example, dispersing individuals are driven by the goals of finding unoccupied breeding habitat while minimizing mortality risk [15].

- Motion Capacity: The physiological and morphological abilities that enable movement, such as locomotion type, speed, and endurance. Lynxes demonstrate two movement modes: one for local exploration and another resembling a Lévy walk for longer-distance travel [15].

- Navigation Capacity: The ability to orient and navigate using external cues. Lynxes evaluate habitat types within their perceptual range and detect potential settlement sites [15].

- External Factors: The biotic and abiotic environmental context that influences movement, including landscape heterogeneity, resources, and conspecifics. Matrix heterogeneity profoundly affects lynx movement success and mortality [15].

The following diagram illustrates the relationships between these components and their connection to population and ecosystem levels:

Scaling from Individuals to Populations and Ecosystems

Individual movement scales to influence population dynamics through several key mechanisms:

- Dispersal and Connectivity: Movement connects local populations, enabling metapopulation dynamics and source-sink systems [15]. In the Iberian lynx system, populations inside the protected National Park act as sources (with birth rates > death rates and emigration > immigration), while those outside function as sinks (net importers) [15].

- Demographic Rates: Movement directly affects birth rates through settlement success and death rates through movement-related mortality. Dispersing lynxes move for an average of 111 days (SD = 152.6), with successful individuals settling faster (55 ± 107 days) than those that die (175 ± 163 days) [15].

- Mobile Links: Moving organisms act as "mobile links" that connect habitats or ecosystems, thereby transferring resources, genes, and propagules between otherwise separate locations [9]. These links can be categorized as:

- Resource Links: Transport of nutrients (e.g., marine nutrients to terrestrial systems)

- Genetic Links: Pollen and seed dispersal enabling gene flow

- Process Links: Modifying ecosystems through herbivory, predation, or engineering

The following diagram illustrates how different movement types create connections across ecological scales:

Quantitative Parameters and Data

Key Movement Parameters in Population Dynamics

The following table summarizes critical quantitative parameters from empirical studies linking individual movement to population dynamics:

Table 1: Key Quantitative Parameters in Movement-Population Dynamics

| Parameter | Measurement | Biological Significance | Example from Iberian Lynx |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dispersal duration | Mean = 111 days (SD = 152.6) [15] | Time invested in finding settlement sites; affects mortality risk | Successful dispersers: 55 ± 107 days; Unsuccessful: 175 ± 163 days [15] |

| Movement modes | Two distinct modes: local exploration & long-distance movement [15] | Adapts search strategy to context; affects path efficiency | Second mode resembles Lévy walk for leaving current area [15] |

| Matrix sensitivity | Mortality risk increases in open habitat [15] | Landscape heterogeneity directly impacts survival | Additive mortality risk when moving in open matrix [15] |

| Source-sink dynamics | Per capita birth (B) > death (D) in sources; E > I for net exporters [15] | Determines metapopulation persistence and stability | Protected areas function as sources; surrounding areas as sinks [15] |

| Settlement success | Dependent on detection of empty territories [15] | Links movement to reproduction and population growth | Breeding habitat detection within perceptual range critical [15] |

Technological Advances in Movement Research

Modern movement ecology has been revolutionized by technological developments that enable detailed tracking of individual organisms:

Table 2: Research Technologies in Movement Ecology

| Technology | Application | Data Type | Spatiotemporal Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|

| GPS tracking | Lagrangian movement paths [6] | Quantitative: positions, speeds | Fine-scale (sub-meter to meters; minutes to hours) [6] |

| Accelerometers | Behavior classification, energy expenditure [6] | Quantitative: acceleration patterns | Very fine-scale (sub-second; body movements) [6] |

| Biologging | Physiology, environment, behavior [6] | Mixed: sensor data with context | Varies by sensor type [6] |

| Genetic markers | Dispersal success, gene flow [9] | Quantitative: genetic differentiation | Generational time scales [9] |

| Stable isotopes | Migration origins, trophic position [9] | Quantitative: isotopic signatures | Seasonal to annual time scales [9] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Integrated Movement-Demography Study Design

To empirically link individual movement to population dynamics, researchers can implement the following comprehensive protocol, adapted from successful studies like the Iberian lynx research [15]:

Objective: Quantify how individual movement behavior influences population parameters (birth, death, emigration, immigration rates) and metapopulation dynamics.

Step 1: Individual Tracking and Movement Path Analysis

- Deploy GPS tags on a representative sample of the population (considering age, sex, social status)

- Collect positional data at intervals appropriate to the study organism's movement capacity (e.g., several fixes per day for mammals)

- Classify movement modes using statistical analysis of step lengths and turning angles

- Map movement paths in relation to landscape features and habitat types

Step 2: Parameterize Movement Submodel

- Internal State: Identify goals (e.g., find mates, avoid predators) through field observation or experimental manipulation

- Motion Capacity: Quantify distributions of daily movement distances and directional persistence across different habitats

- Navigation Capacity: Determine perceptual range and habitat selection rules through controlled experiments or path analysis

- External Factors: Map landscape heterogeneity, including barriers, corridors, and varying mortality risks

Step 3: Integrate with Demographic Monitoring

- Conduct simultaneous monitoring of birth and death rates in each subpopulation

- Mark individuals to track emigration and immigration between subpopulations

- Record settlement events and territory occupancy in relation to movement paths

- Monitor habitat quality and resource availability across patches

Step 4: Implement Spatially Explicit Individual-Based Model

- Create a simulation that incorporates the movement submodel with demographic processes

- Validate model outputs against empirical data on connectivity and population trends

- Conduct sensitivity analysis to identify parameters with strongest influence on population growth

Step 5: Analyze Source-Sink Dynamics and Metapopulation Structure

- Calculate per capita birth (B), death (D), emigration (E), and immigration (I) rates for each patch

- Classify patches as sources (B > D, E > I) or sinks (B < D, E < I)

- Quantify connectivity matrices between patches based on observed movements

- Estimate metapopulation growth rate and extinction risk

Measuring Mobile Links and Ecosystem Effects

Objective: Quantify how organism movement creates connections between ecosystems and influences ecosystem processes.

Protocol:

- Tag Organisms and Track Movements: Use appropriate tracking technology (GPS, radio telemetry) to document movement paths between ecosystem types

- Measure Transferred Materials:

- For nutrient transporters: Collect feces, urine, or carcasses and analyze nutrient content

- For seed dispersers: Collect feces and germinate seeds or use DNA barcoding to identify seeds

- For ecosystem engineers: Quantify bioturbation rates or structural modifications

- Quantify Ecosystem Impacts:

- Establish paired experimental plots with and without organism access

- Measure nutrient concentrations, soil properties, and plant community composition

- Use stable isotopes to trace nutrient flows from mobile consumers

- Experimental Manipulations:

- Use enclosures/exclosures to isolate effects of specific mobile linkers

- Conduct removal experiments to assess ecosystem responses to lost connections

- Simulate pulse events (e.g., mass migrations) to measure ecosystem resilience

Research Tools and Reagents

Essential Research Solutions for Movement Ecology

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Movement Studies

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tracking Hardware | GPS loggers, VHF transmitters, accelerometers, geolocators [6] | Collect movement path data at various spatiotemporal scales | Weight restrictions (<5% body mass), battery life, data retrieval method |

| Environmental Data | Remote sensing imagery, habitat maps, climate data [15] | Characterize external factors affecting movement | Resolution matching (temporal and spatial), classification accuracy |

| Genetic Analysis | Microsatellites, SNP genotyping, DNA sequencing [9] | Determine relatedness, population structure, dispersal success | Tissue sampling method, marker variability, statistical power |

| Stable Isotopes | δ¹⁵N, δ¹³C, δ²H [9] | Trace origins, migrations, and trophic positions | Reference databases, tissue turnover rates, geographic resolution |

| Statistical Software | R packages (move, amt, bayesmove) [6] | Analyze movement paths, habitat selection, space use | Computational requirements, learning curve, model flexibility |

| Simulation Platforms | Individual-based modeling frameworks (NetLogo, RangeShifter) [15] | Integrate movement with population dynamics | Parameterization requirements, validation methods, computational intensity |

Applications and Case Studies

Iberian Lynx Metapopulation Dynamics

The Iberian lynx study provides a seminal example of linking individual movement to population dynamics [15]. Researchers integrated:

- Movement Submodel: Based on empirical tracking of 30 lynxes, incorporating internal state (find breeding habitat, minimize risk), motion capacity (two movement modes), and navigation capacity (habitat assessment)

- Demographic Submodel: Survival probabilities based on location (higher inside protected park) and reproduction limited by territory availability

- Landscape Structure: Patches of breeding habitat embedded in a heterogeneous matrix with varying mortality risks

Key findings demonstrated that:

- Matrix heterogeneity strongly influenced connectivity and dispersal success

- Movement parameters were highly sensitive to dynamic demographic variables

- Source-sink dynamics emerged from the interaction between movement behavior and spatial variation in mortality

- The system exhibited high extinction probability due to demographic stochasticity and movement limitations

Migratory Species as Ecosystem Engineers

Migratory animals can function as potent mobile links that transport nutrients and energy across ecosystem boundaries [9]. Notable examples include:

- Sea-to-Land Nutrient Transport: Anadromous fish (e.g., salmon) transport marine-derived nutrients to freshwater and terrestrial systems

- Cross-Continental Connectors: Migratory birds connect Arctic breeding grounds with tropical wintering areas, transporting nutrients, parasites, and energy

- Pulsed Herbivory Effects: Large mammal migrations (e.g., wildebeest) create massive pulses of herbivory and nutrient redistribution

These mobile links can be quantified through:

- Stoichiometric analysis of nutrient composition in consumer tissues and wastes

- Stable isotope tracing of nutrient origins and incorporation into food webs

- Experimental exclusions to measure ecosystem responses to lost connections

- Comparative studies along migration gradients or before/after migration collapse

The following diagram illustrates how migratory species create long-distance ecosystem connections:

Future Directions and Synthesis

The integration of movement ecology with population and ecosystem science continues to evolve rapidly. Promising research directions include:

- Movement Forecasting: Developing predictive models of animal movement in response to environmental change [16]

- Cross-Scale Integration: Understanding how movement processes are conserved across organizational levels [16]

- Human-Movement Interactions: Investigating how human mobility and animal movement interact in the Anthropocene [6] [16]

- Conservation Applications: Using movement understanding to design protected area networks and mitigate fragmentation effects [15] [9]

- Technological Innovation: Leveraging advances in sensor technology, data transmission, and computational analysis [6]

The mechanistic approach provided by the Movement Ecology Framework enables researchers to move beyond descriptive pattern analysis to truly understand the processes linking individual decisions to population dynamics and ecosystem function. This understanding is critical for addressing pressing conservation challenges in human-modified landscapes and climate change scenarios.

Movement ecology formally coalesced as a defined scientific discipline in the early 21st century, establishing a unified framework to understand the causes, mechanisms, patterns, and consequences of organism movement [17]. This field synthesizes insights from empirical data collection and theoretical models to address fundamental questions about why, how, where, and when animals move across a range of spatio-temporal scales [17]. The genesis of movement ecology as a distinct field marked a pivotal shift from purely descriptive tracking studies to an integrative science that connects internal state, navigation capacity, motion capacity, and external factors [2] [18]. This transition was largely catalyzed by technological revolutions in tracking technology, the proliferation of movement data, and the pressing need to understand movement's role in ecological processes and conservation challenges [17] [16]. The discipline now provides critical insights for conservation, invasive species control, and ecological monitoring, with direct applications for predicting species responses to anthropogenic environmental change [17].

The Technological Revolution: From Observation to Quantification

The field's historical trajectory is inextricably linked to technological advancement. Early animal movement studies relied on direct observation and manual tracking, fundamentally limiting the scale and resolution of data collection. The development of animal-borne tracking devices (biologgers) represents a cornerstone in the field's evolution [18]. Initially, devices were prohibitively expensive, large, and inefficient, restricting their use to larger species [18]. Over recent decades, a paradigm shift occurred as GPS devices and accelerometers became cheaper, smaller, and more efficient, creating opportunities for obtaining individual-level information on a greater number and diversity of animals [18].

Contemporary tracking systems now integrate multiple sensor types. Hardware typically includes GPS modules, accelerometers, and communication modules like LTE or LoRaWAN, while the software side involves data processing, storage, and analysis platforms that interpret raw data into actionable insights [19]. The integration of machine learning algorithms has further enhanced the ability to identify complex patterns, such as migration routes or health anomalies, from these rich datasets [19]. This technological progression has generated an explosion of movement data, enabling more refined recordings of animal movement paths and facilitating the examination of physiological aspects of movement through sensors monitoring respiratory rate, body temperature, and other biologging metrics [17] [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Technologies

Table 1: Key technologies and methodologies in modern movement ecology research.

| Technology/Reagent | Primary Function | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| GPS Tracking Devices | Records high-resolution location data in real-time. | Mapping movement paths, identifying home ranges, and quantifying migration routes [19] [17]. |

| Accelerometers | Measures fine-scale body movement and orientation. | Inferring animal behavior (e.g., foraging, resting), energy expenditure, and classifying behavioral modes [19] [18]. |

| Biologgers | Collects behavioral and physiological data (e.g., heart rate, temperature). | Examining physiological aspects of movement and linking internal state to movement decisions [18]. |

| Virtual Fencing Collars | Provides remote spatiotemporal control of animal movement using audio and electrical cues. | Experimental manipulation of animal distribution and movement in natural settings; studying navigation and behavioral responses [18]. |

| Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) | Enables individual animal identification and monitoring at specific points. | Controlling access to resources in smart feeding systems, recording weight, and monitoring individual intake [18]. |

| Precision Ranching Technology | Integrates sensor technology for high-resolution remote monitoring of livestock and resources. | Serves as a model system for studying movement ecology with enhanced experimental control and data collection [18]. |

Foundational Principles and Conceptual Frameworks

The theoretical underpinnings of movement ecology are captured in a unified framework that seeks to understand the ecological and evolutionary causes and consequences of movement by focusing on four core components: the internal state of an organism (why it moves), its navigation capacity (how it orientates), its motion capacity (how it moves), and the role of external factors (how the environment influences movement) [18]. This framework allows researchers to dissect movement processes across scales, from local foraging and home-range use to seasonal migrations spanning continents [17].

A key conceptual advancement has been the development of multi-scale analytical frameworks. Getz proposed a hierarchical movement track segmentation framework that partitions an individual's trajectory into a nested hierarchy of behavioral modes and phases [17]. This framework anchors movement analysis by defining fundamental movement elements and canonical activity modes—such as localised foraging bouts, commuting trips, and resting periods—that can be identified from tracking data and linked to larger-scale phases like seasonal migrations [17]. This approach aims to improve forecasts of how animals adapt their space use under environmental change by understanding scaling-up rules—how changes in short-term movement behavior aggregate into longer-term range shifts [17].

Logical Workflow: From Data Collection to Ecological Insight

Methodological Advances: Quantitative Frameworks

The development of sophisticated analytical methods has been equally important as technological progress in establishing movement ecology as a rigorous discipline. Quantitative approaches now enable researchers to move beyond descriptive pattern analysis to mechanistic understanding and prediction.

Reaction-diffusion theory from statistical physics has been applied to quantify encounters between moving animals, addressing a core ecological question [17]. Das et al. derived analytical expressions for first-encounter probabilities between animals moving within home ranges, demonstrating that treating encounters as first-passage events yields well-behaved probabilities, whereas an approach based on joint occupancy produces non-normalised measures [17]. This work provides a rigorous approach for quantifying encounter and interaction rates relevant to processes like predation, infectious disease transmission, and social contacts among animals [17].

Energy-informed movement modeling represents another significant methodological advancement. Ranjan et al. combined movement modelling with climate data to unravel the long-distance migration of Pantala flavescens, the globe-skimmer dragonfly [17]. They modified Dijkstra's algorithm to include the dragonfly's flight-time energy constraints and incorporated seasonal wind patterns, running this model on wind data to yield a plausible migration network linking India and East Africa [17]. This integration of movement ecology with atmospheric science reveals the drivers of insect migrations and identifies critical stopover habitats for conservation.

Table 2: Key methodological approaches in movement ecology analysis.

| Analytical Method | Theoretical Foundation | Application in Movement Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Reaction-Diffusion Theory | Statistical Physics | Quantifying encounter rates between individuals for understanding predation, disease transmission, and social interactions [17]. |

| Hierarchical Bayesian Models | Bayesian Statistics | Understanding multi-scale movement processes and incorporating uncertainty in movement parameters [17]. |

| Machine Learning Classification | Computer Science | Identifying behavioral states from movement trajectories and accelerometer data [19] [17]. |

| Network Analysis | Graph Theory | Modeling connectivity between habitats and identifying critical movement corridors [17]. |

| Path Segmentation Algorithms | Movement Ecology | Partitioning continuous movement tracks into discrete behavioral phases and modes [17]. |

| Energy-Informed Network Models | Optimal Foraging Theory | Predicting long-distance migration routes based on energetic constraints and environmental conditions [17]. |

Experimental Approaches: Establishing Causality

While early movement ecology relied heavily on observational studies, the field has increasingly recognized the need for experimental approaches to establish causal relationships and uncover underlying mechanisms [20]. This shift represents an important maturation of the discipline, moving from correlation to causation.

Experimental manipulations in both laboratory and natural settings provide a promising way forward to generate mechanistic understandings of the drivers, consequences, and conservation of animal movement [20]. For instance, Papadopoulou et al. investigated how bird flocks respond to predation threats through coordinated turning using GPS-tracked pigeons under simulated attacks by a robotic predator [17]. By combining this empirical data with agent-based modeling, they analyzed how individuals within a flock rearrange their relative positions during collective escape manoeuvres, offering a novel metric for quantifying coordinated movement under threat [17].

Rangeland-based livestock operations have emerged as particularly valuable model systems for experimental movement ecology [18]. These systems provide robust, readily accessible individual-level genealogical and life history information; complete herd-level coverage with spatial tracking and physiological monitoring; and opportunities for straightforward and safe experimental manipulation of population and environmental characteristics to an extent that is infeasible in wild populations [18]. This experimental framework enables researchers to address fundamental questions about how nutritional state affects movement patterns, the roles of genetics versus social learning in determining movement traits, how movement traits affect life history syndromes, and how population density affects movement patterns [18].

Experimental Protocol: Livestock as a Model System

Future Directions and Integrative Applications

As movement ecology continues to mature, several frontier areas represent the evolving trajectory of the discipline. A key challenge involves scaling up from individual-level analyses to community and ecosystem-level processes [17]. Understanding how interactions among individuals and species shape movement decisions is crucial for uncovering broader dynamics in food webs and species assemblages [17]. This may involve tracking multiple species simultaneously, detecting feedback loops between movement and resource availability, or modeling how behavioral adaptations influence broader ecological patterns [17].

Another frontier is integrating movement ecology more explicitly with ecosystem function [17]. Animal movements drive essential processes such as pollination, seed dispersal, nutrient redistribution, and disease transmission. Quantifying these links requires connecting movement data with biogeochemical flows, interaction networks, and habitat connectivity [17]. Doing so can help clarify the role of mobile species as ecosystem engineers or as vectors of change across fragmented landscapes.

The field is also moving toward enhanced predictive capacity for conservation applications. Ferreira et al. demonstrated this approach by compiling satellite tracking data from 484 individuals across six marine megafauna species and overlaying these movement data with maps of anthropogenic threats [17]. This multi-species assessment revealed distinct hotspots where critical habitats overlap with multiple threats, providing science-based guidance for mitigation measures such as adjusting shipping lanes or expanding protected areas [17]. This exemplifies 'biologging meets threat mapping'—combining animal movement data with human footprint data to inform proactive conservation and policy decisions [17].

Continued progress will rely on further refinement of tracking technologies—including smaller, longer-lasting, and more versatile tags—as well as on improved remote sensing of habitat conditions and climate variables [17]. Advances in machine learning and data assimilation will be increasingly important for analysing large-scale, high-dimensional movement datasets [17]. Combining these tools with mechanistic models will improve the ability to anticipate how animals respond to shifting environments, from altering migration routes to adapting species interactions in the face of global change [17].

Modern Tools and Workflows: Tracking Technology, Data Analysis, and Model Implementation

The study of animal movement has undergone a revolutionary transformation with the advent of biologging technology. Biologging refers to the use of animal-borne sensors ('bio-loggers') to record data on animal physiology, behavior, and environmental conditions [21]. This technological revolution has enabled researchers to move from sparse location points to rich, high-resolution datasets that capture the intricate details of how animals interact with their environment across multiple spatiotemporal scales [22] [23]. The paradigm-changing opportunities of biologging sensors for ecological research are vast, fundamentally altering how we investigate animal movement, behavior, and ecological processes [22].

This revolution aligns with the Movement Ecology Paradigm, a conceptual framework that integrates four basic mechanistic components of organismal movement: the internal state (why move?), motion capacity (how to move?), navigation capacity (when and where to move?), and the external factors affecting movement [24]. Biologging provides the empirical tools to quantify these components simultaneously, enabling unprecedented insights into the causes, mechanisms, patterns, and consequences of movement across diverse taxa [24] [25]. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical guide to the core technologies, analytical frameworks, and applications driving the biologging revolution in movement ecology research.

The Movement Ecology Framework: A Theoretical Foundation

The Movement Ecology Paradigm, introduced by Nathan et al. (2008), offers a unified conceptual framework for studying organismal movement [24]. This framework asserts that movement paths emerge from the interplay of four core components:

- Internal State: The intrinsic motivations driving movement, including physiological needs (hunger, thirst) and reproductive demands [24]

- Motion Capacity: The biomechanical and physiological abilities enabling movement, such as running, flying, or swimming [24]

- Navigation Capacity: The abilities to orient and direct movement through space and time [24]

- External Factors: All environmental aspects affecting movement, including resources, predators, and physical barriers [24]

Biologging technology provides the means to measure these components simultaneously in wild, free-ranging animals, creating opportunities to develop and test mechanistic movement theories [22] [24]. This represents a significant advancement beyond descriptive studies, enabling researchers to understand the fundamental processes underlying observed movement patterns.

Table: The Four Components of the Movement Ecology Framework

| Component | Definition | Biologging Measurement Tools |

|---|---|---|

| Internal State | Organism's intrinsic motivation to move | Heart rate monitors, body temperature sensors, hormone samplers |

| Motion Capacity | Organism's fundamental movement abilities | Accelerometers, gyroscopes, electromyography sensors |

| Navigation Capacity | Ability to determine direction and timing of movement | Magnetometers, GPS, light-based geolocators |

| External Factors | Environmental conditions affecting movement | Temperature sensors, salinity sensors, cameras, microphones |

The Biologging Toolkit: Sensor Technologies and Capabilities

Core Sensor Types and Their Applications

Modern biologgers integrate multiple sensors to provide comprehensive monitoring of animal status and environmental conditions. The most widely used sensors include:

GPS Receivers: Provide high-precision location data, enabling researchers to reconstruct movement paths and home ranges with unprecedented accuracy [26] [27]. Modern GPS tags can record locations with meter-scale accuracy at programmable intervals from seconds to hours [27].

Accelerometers: Tri-axial accelerometers measure dynamic acceleration in three dimensions (surge, heave, sway), providing detailed information on body posture, movement intensity, energy expenditure, and specific behaviors [22] [27]. Sampling rates typically range from 1-100 Hz, capturing everything from subtle head movements to strenuous locomotion [27].

Magnetometers: Tri-axial magnetometers measure the strength and direction of Earth's magnetic field relative to the animal's body orientation, providing crucial data for determining compass heading when combined with accelerometer data for tilt compensation [27].

Environmental Sensors: A suite of sensors including temperature, salinity, pressure/depth, light, and humidity sensors that record the physical conditions experienced by the animal [21] [28]. These measurements serve dual purposes for understanding animal ecology and contributing to environmental monitoring [28].

Integrated Multi-Sensor Platforms

The true power of modern biologging emerges from integrated multi-sensor approaches that combine complementary data streams [22] [27]. For example, a typical integrated multi-sensor collar (IMSC) for terrestrial mammals might include:

- GPS receiver for position fixes

- Tri-axial accelerometer for behavior and energy expenditure

- Tri-axial magnetometer for heading information

- Temperature sensor for environmental context

- VHF transmitter for collar recovery [27]

Such integration enables sophisticated analyses like dead-reckoning, which uses vector integration of acceleration and magnetic heading data between GPS fixes to reconstruct highly detailed movement paths [27]. This approach can resolve movements at the scale of individual body lengths, providing unprecedented resolution of animal movement trajectories.

Table: Biologging Sensor Types and Their Primary Applications in Movement Ecology

| Sensor Type | Measured Parameters | Primary Ecological Applications | Common Sampling Rates |

|---|---|---|---|

| GPS | Latitude, longitude, altitude, speed | Movement paths, home range, habitat selection | 1 sec to several hours |

| Accelerometer | Dynamic acceleration on 3 axes | Behavior identification, energy expenditure, gait analysis | 1-100 Hz |

| Magnetometer | Magnetic field strength on 3 axes | Compass heading, orientation behavior | 1-100 Hz |

| Gyroscope | Angular velocity, rotation | Complex maneuvering, flight dynamics | 1-100 Hz |

| Depth Sensor | Pressure, dive depth | Dive profiles, aquatic foraging behavior | 1-10 Hz |

| Temperature Sensor | Ambient/body temperature | Thermal ecology, microclimate use | 0.1-1 Hz |

| Light Sensor | Light intensity | Geolocation, activity patterns | 0.1-1 Hz |

Analytical Frameworks: From Raw Data to Ecological Insight

Machine Learning for Behavior Classification

A central challenge in biologging is translating raw sensor data into ecologically meaningful information about animal behavior. Supervised machine learning has emerged as a powerful approach for this task [29]. The standard workflow involves:

- Data Collection: Deploying bio-loggers on animals to record sensor data

- Ground Truthing: Simultaneously observing and annotating animal behaviors to create labeled training data

- Model Training: Using the labeled data to train ML algorithms to recognize behavior-specific sensor signatures

- Prediction: Applying the trained model to classify behaviors in unlabeled sensor data [29]

Recent benchmarking through the Bio-logger Ethogram Benchmark (BEBE)—the largest publicly available benchmark of its type, comprising 1654 hours of data from 149 individuals across nine taxa—has demonstrated that deep neural networks generally outperform classical machine learning methods like random forests across diverse datasets [29]. Furthermore, self-supervised learning approaches, where models are pre-trained on large unlabeled datasets (including human activity data), show particular promise for settings with limited training data [29].

Multi-Scale Movement Analysis

Movement occurs across multiple spatiotemporal scales, from fine-scale foraging decisions to annual migration patterns [26] [24]. Biologging data enables researchers to analyze these nested scales simultaneously:

- Fine-scale movements (seconds to minutes, meters to kilometers): Analyzed using high-frequency accelerometer and magnetometer data to identify specific behaviors (foraging, resting, traveling) and movement modes [27]

- Intermediate-scale movements (hours to days, home range scale): Analyzed using GPS data combined with environmental sensors to understand habitat selection and resource use [26]

- Broad-scale movements (seasons to years, migratory scales): Analyzed using long-term location data to identify migratory routes, dispersal events, and range shifts [26] [24]

The Movement Ecology Framework facilitates integration across these scales by providing a common conceptual foundation for understanding how internal states, motion capacities, navigation capacities, and external factors interact across hierarchical levels of organization [24].

Data Management and Standardization Platforms

The large volumes of data generated by biologging sensors—often referred to as "big data" in movement ecology—present significant challenges for data management, sharing, and preservation [22] [21]. Several platforms have been developed to address these challenges:

- Movebank: A global platform for managing, sharing, and analyzing animal movement data, containing over 7.5 billion location points and 7.4 billion other sensor records across 1478 taxa as of January 2025 [21]

- Biologging intelligent Platform (BiP): An integrated platform that standardizes sensor data and metadata according to international standards, facilitating secondary use across disciplines [21]

- U.S. Animal Telemetry Network (ATN): A national network that aggregates marine animal telemetry data, including oceanographic profiles collected by animal-borne sensors [28]

These platforms implement standardized data formats and metadata conventions (e.g., Integrated Taxonomic Information System, Climate and Forecast Metadata Conventions), enabling interoperability and collaborative research [21]. Standardization is particularly important for maximizing the value of biologging data, as inconsistent data formats and incomplete metadata have historically limited data integration and reuse [21].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Integrated Multi-Sensor Collar Deployment

A representative experimental protocol for terrestrial mammals involves the deployment of integrated multi-sensor collars, as demonstrated in wild boar (Sus scrofa) research [27]:

Collar Specifications:

- Sensors: GPS, tri-axial accelerometer, tri-axial magnetometer

- Accelerometer range: ±8 g

- Sampling rate: 10 Hz for all sensors

- GPS fix interval: 30 minutes

- Power source: 4-D cell battery pack

- Total deployment weight: 716 g (≤2% of body weight for adult boar)

- Data storage: 32 GB MicroSD card

- Additional features: VHF beacon for recovery, drop-off mechanism [27]

Deployment Protocol:

- Capture animals using corral traps or dart tranquilization

- Secure collar ensuring proper sensor orientation relative to body axes

- Collect calibration data for magnetometer (hard-iron and soft-iron corrections)

- Release animal and monitor via VHF signals

- Recover collars using VHF signals after predetermined deployment period or via drop-off mechanism

- Download data and perform initial quality checks [27]

Validation Procedures:

- Behavioral validation: Video record collared animals in semi-natural enclosures to create ground-truthed datasets for behavior classification model training

- Magnetic heading validation: Compare compass headings derived from magnetometer data with known orientations in both laboratory and field settings

- GPS accuracy assessment: Compare GPS fixes with known locations to quantify positioning error [27]

Sensor Calibration and Data Validation

Rigorous calibration is essential for ensuring data quality, particularly for sensors like magnetometers that are sensitive to environmental interference:

Magnetometer Calibration:

- Purpose: Correct for hard-iron (permanent magnetic fields) and soft-iron (induced magnetic fields) distortions

- Method: Rotate sensor through multiple orientations while recording magnetometer readings