Morphological Spatial Pattern Analysis (MSPA): A Powerful Framework for Ecological Security and Landscape Connectivity

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of Morphological Spatial Pattern Analysis (MSPA), a powerful image-processing technique for analyzing ecological landscape structure.

Morphological Spatial Pattern Analysis (MSPA): A Powerful Framework for Ecological Security and Landscape Connectivity

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of Morphological Spatial Pattern Analysis (MSPA), a powerful image-processing technique for analyzing ecological landscape structure. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we detail MSPA's core principles in quantifying landscape patterns like cores, bridges, and branches. The scope extends from foundational concepts and methodological workflows—including integration with habitat connectivity assessment and circuit theory—to troubleshooting common challenges and validating results through comparative analysis with other spatial metrics. This guide serves as a critical resource for applying MSPA in ecological research, land-use planning, and environmental impact assessment, highlighting its role in constructing robust ecological security patterns.

What is MSPA? Understanding the Foundations of Landscape Morphology

Morphological Spatial Pattern Analysis (MSPA) is a customized sequence of mathematical morphological operators designed for the precise description of image component geometry and connectivity [1]. This methodology, based solely on geometric concepts, is scale-independent and applicable to any type of digital image across numerous application fields [1]. In ecological research, MSPA has emerged as a powerful technique for quantifying landscape patterns, particularly through the analysis of binary land cover maps such as forest/non-forest masks [2] [3] [1]. The analysis divides foreground areas into seven mutually exclusive pattern classes that collectively describe spatial configuration in meaningful ecological terms [1]. Originally developed as a general image processing technique, MSPA has become increasingly valuable in ecology for identifying critical habitat patches and connectivity pathways that inform conservation planning and landscape management [3] [4].

The MSPA Classification Scheme

The Seven Fundamental MSPA Classes

The MSPA algorithm processes a binary input image (where foreground represents the habitat of interest and background represents all other land cover types) and classifies each foreground pixel into one of seven distinct pattern classes [1]. These classes provide a structural description of the spatial pattern with specific ecological interpretations for habitat analysis.

Table 1: The Seven Fundamental MSPA Pattern Classes and Their Ecological Interpretations

| MSPA Class | Structural Description | Ecological Interpretation | Conservation Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core | Interior areas of habitat patches | High-quality habitat areas buffered from edge effects | Primary conservation targets; often designated as ecological sources [2] [5] |

| Islet | Small, isolated habitat patches | Small habitats with potential value for specialists | May serve as stepping stones for species movement [3] |

| Perforation | Transition zones between core and internal background | Habitat edges surrounding internal non-habitat areas | Ecological transitions; often managed differently than core areas |

| Edge | External habitat boundaries | Habitat periphery with different microclimate conditions | Filter for species movement between core and non-habitat |

| Loop | Corridors connecting different parts of the same core area | Alternative pathways for internal habitat connectivity | Provides redundancy in movement routes within habitats |

| Bridge | Corridors connecting different core areas | Landscape connectivity facilitating species movement | Key conservation priorities for maintaining population connectivity [3] |

| Branch | Corridors connecting core areas to non-core elements | Pathways from core habitats to smaller patches | Potential species movement routes to stepping stones |

MSPA Technical Parameters

MSPA analysis requires the specification of four key parameters that influence pattern classification [1]:

- Foreground Connectivity (4- or 8-connectivity): Determines how pixels are considered connected—either through their edges (4-connectivity) or including diagonals (8-connectivity).

- Edge Width: Defines the thickness of the edge and perforation zones, directly affecting core area delineation.

- Transition: Controls whether transition pixels (loop or bridge pixels that traverse an edge or perforation) are displayed as separate elements.

- Intext: Determines whether internal background areas (within foreground objects) receive additional classification.

These parameters must be carefully selected based on the specific research questions, species characteristics, and spatial scale of analysis [1].

MSPA in Ecological Research Workflow

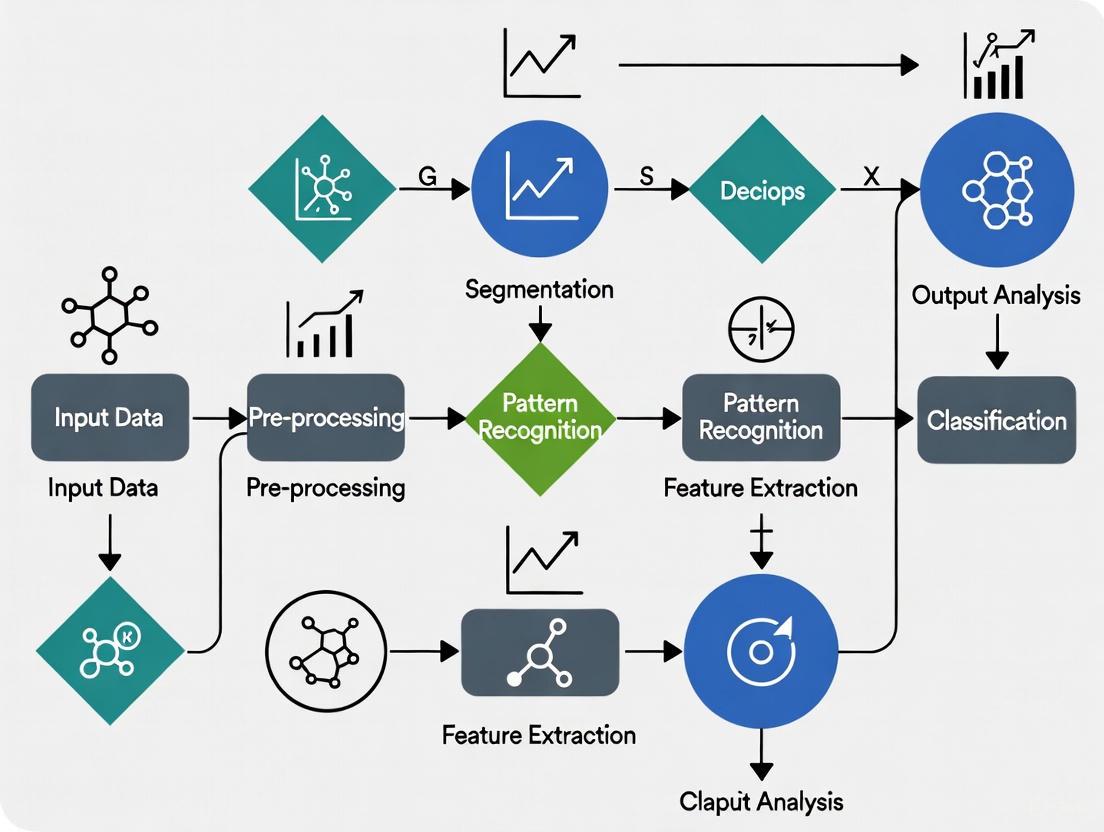

The application of MSPA in ecological research follows a structured workflow that transforms raw spatial data into actionable ecological insights. The diagram below illustrates this integrated methodological framework.

Diagram 1: Integrated MSPA Ecological Research Workflow. This flowchart illustrates the sequential process from land cover data to ecological network delineation, highlighting the central role of MSPA in identifying core habitats and structural connectivity.

MSPA Integration with Ecological Models

Coupling MSPA with Circuit Theory and MCR Models

In contemporary ecological research, MSPA is rarely used in isolation. It is most powerful when integrated with ecological models such as the Minimal Cumulative Resistance (MCR) model and circuit theory to construct comprehensive ecological networks [2] [5] [3]. This integration follows a systematic protocol:

Ecological Source Identification: MSPA-derived core areas serve as primary ecological sources in the network [3] [4]. For example, in a study of Shenzhen City, ten core areas identified through MSPA were used as ecological sources for network construction [3].

Resistance Surface Development: Landscape resistance surfaces are created based on factors such as land use type, elevation, slope, vegetation index, and human disturbance intensity [5] [4].

Corridor and Node Delineation: Circuit theory or MCR models are applied to identify ecological corridors, pinch points, and barrier points between MSPA-identified sources [2] [5].

Table 2: MSPA Integration Protocols in Recent Ecological Studies

| Study Area | MSPA Ecological Sources | Integrated Model | Key Outputs | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| South China Karst Desertification Control Forests [2] | Core areas from forest masks | Circuit Theory | 68-113 ecological corridors; 20-67 ecological nodes | Hierarchical ESP construction for karst desertification control |

| Fuzhou Metropolitan Area [5] | Woodland core areas with habitat connectivity assessment | PLUS and MCR models | 35 ecological corridors; 42 ecological nodes | "Three cores, three areas, multiple corridors" pattern for urban planning |

| Shenzhen City [3] | Ten core areas with maximum importance patch values | MCR and gravity models | Important corridors, stepping stones (35), ecological fault points (17) | Urban ecological network optimization |

| Beijing [4] | Core areas (96.17% of all MSPA types, 82.01% forest) | MCR model with connectivity index | 45 ecological corridors (8 major, 37 ordinary); 29 stepping stones | High-density urban ecological environment sustainability |

Comparative Analysis of MSPA Applications

The application of MSPA varies significantly across different ecological contexts and research objectives. The table below summarizes key methodological variations in recent studies.

Table 3: Methodological Variations in MSPA Applications Across Ecosystems

| Methodological Aspect | Karst Desertification Areas [2] | Metropolitan Regions [5] | Fragmented Urban Landscapes [3] [4] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Habitat Focus | KDC forests | Woodland (over 80% of area) | Forest patches within urban matrix |

| MSPA Scale Setting | Tailored to karst forest patch distribution | Adjusted for metropolitan woodland connectivity | Optimized for urban forest fragmentation |

| Key Challenges Addressed | Severe fragmentation; internal degradation | Urban expansion; habitat fragmentation | Landscape connectivity loss; biodiversity decline |

| Ecorical Sources Criteria | MSPA cores with connectivity analysis | MSPA cores with habitat quality assessment | MSPA cores with landscape index evaluation |

| Supplementary Data | NDVI; karst desertification severity | Land use simulation (PLUS model) | Nighttime light data; human disturbance index |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Binary Mask Preparation Protocol

The quality of MSPA results depends fundamentally on appropriate binary mask preparation [1]:

Data Acquisition: Obtain high-resolution land cover data (30m resolution recommended) [3] [4]. The GlobeLand30 dataset or similar sources provide suitable baseline data.

Habitat Classification: Classify the landscape into binary categories (foreground/background) based on research objectives. Common classifications include:

Spatial Resolution Consideration: Ensure pixel size aligns with species mobility scales and research questions. Finer resolutions detect smaller habitat elements but increase processing requirements.

Projection and Alignment: Convert all spatial data to a consistent coordinate system (e.g., UTM WGS_1984) using GIS software such as ArcGIS or QGIS [4].

MSPA Parameter Configuration Protocol

Optimal MSPA parameter settings vary by research context [1]:

Connectivity Selection:

- Use 8-connectivity for highly mobile species or continuous habitat processes

- Use 4-connectivity for less mobile species or to reduce diagonal connectivity effects

Edge Width Determination:

- Set based on known edge effect distances for target species

- Typical range: 1-5 pixels (30-150m at 30m resolution)

- Conduct sensitivity analysis with multiple values to assess robustness

Transition Parameter:

- Set to "show" when analyzing connectivity pathways

- Set to "hide" when focusing on closed perimeter characteristics

Intext Setting:

- Enable (Intext=1) for detailed analysis of internal background structures

- Disable (Intext=0) for simplified seven-class output

Ecological Source Identification Protocol

Following MSPA analysis, core areas are evaluated as potential ecological sources [3] [4]:

Core Area Extraction: Isolate MSPA core areas from other pattern classes.

Landscape Metric Calculation: Compute connectivity indices (e.g., patch importance value, connectivity probability) for each core area.

Source Selection: Apply threshold criteria (e.g., minimum patch size, connectivity value) to identify the most significant core areas as ecological sources.

Validation: Compare selected sources with field data on species distribution or expert knowledge when available.

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools and Data Resources for MSPA Ecological Research

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| GuidosToolbox (GTB) | Software package | MSPA implementation with additional image processing tools | Free download; includes MSPA functionality [1] |

| GuidosToolbox Workbench (GWB) | Workflow platform | Extended MSPA analysis with batch processing capabilities | Free download; enhanced version of GTB [1] |

| ArcGIS Plugin | GIS extension | MSPA integration within Esri's ArcGIS platform | Available with documentation [1] |

| QGIS3 Plugin | GIS extension | Open-source MSPA implementation | Available with installation guidelines [1] |

| R Package | Statistical programming integration | MSPA analysis within R environment | Available for computational statistics integration [1] |

| GlobeLand30 | Data resource | 30m resolution global land cover data | http://www.globallandcover.com/ [4] |

| Google Earth Engine | Processing platform | Cloud-based geospatial analysis including binary mask preparation | Accessible via web platform |

| Global Forest Watch | Data resource | Forest cover change data for forest/non-forest masks | Online platform with downloadable data |

Advanced Analytical Framework

The integration of MSPA with dynamic simulation models represents the cutting edge of ecological pattern research. The PLUS (Patch-based Land Use Simulation) model coupled with MSPA enables researchers to project future ecological patterns under different scenarios [5]. This advanced protocol involves:

Historical Land Use Analysis: Examining land use changes across multiple time periods (e.g., 2000, 2010, 2020) to identify change trajectories [5].

Future Scenario Development: Simulating land use patterns under ecological priority scenarios using the PLUS model [5].

Dynamic MSPA Application: Applying MSPA to simulated future land use patterns to anticipate changes in core areas, corridors, and connectivity.

Preemptive Conservation Planning: Using projected MSPA results to identify areas at risk of fragmentation and prioritize conservation interventions.

This integrated approach moves beyond static pattern description to dynamic pattern prediction, enabling proactive rather than reactive conservation planning. As demonstrated in the Fuzhou Metropolitan Area study, this methodology can significantly improve woodland fragmentation under ecological priority scenarios by 2030 [5].

Morphological Spatial Pattern Analysis (MSPA) is a customized sequence of mathematical morphological operators designed to describe the geometry and connectivity of image components [1] [6]. As a pixel-based image analysis technique, MSPA classifies the foreground of a binary image into seven mutually exclusive, visually distinct morphological classes: Core, Islet, Perforation, Edge, Loop, Bridge, and Branch [1] [6]. Since its methodology is based solely on geometric concepts, MSPA can be applied at any scale and to any type of digital image across numerous application fields, including landscape ecology, urban planning, manufacturing quality control, and medical imaging [1].

The strength of MSPA lies in its ability to transform a simple binary map (e.g., forest/non-forest or green space/non-green space) into a detailed map of structural patterns that can inform functional connectivity [1] [3]. This provides researchers with a powerful tool to quantify spatial patterns, with particular emphasis on the connections between different parts of a landscape as measured at varying analysis scales [7]. The analysis results in numerous mutually exclusive feature classes which, when merged, exactly reconstitute the original foreground area [1].

The Seven MSPA Classes: Definitions and Ecological Significance

The following table provides detailed definitions and ecological interpretations for each of the seven primary MSPA classes.

Table 1: Definitions and ecological significance of the seven MSPA classes.

| MSPA Class | Morphological Definition | Ecological Significance & Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Core [1] [3] | The interior area of foreground patches. | Represents the most ecologically stable habitat interiors, crucial for supporting sensitive species and maintaining core ecological processes. These areas typically provide the highest habitat quality [3]. |

| Islet [1] [6] | Small, isolated foreground patches. | Represents small, isolated habitats with limited ecological value due to their size and isolation. They may serve as minor stepping stones but are highly susceptible to edge effects [8]. |

| Perforation [1] [6] | The internal background pixels that form "holes" inside core areas. | The transition zone from the core to the internal background. Ecologically, it can represent natural openings or human-induced perforations within a habitat matrix [1]. |

| Edge [1] [3] | The outer boundary of foreground patches, located between the core and the external background. | Acts as a transition zone between habitat interiors and the surrounding matrix. While important for certain edge species, a high proportion of edge can indicate habitat fragmentation and increased exposure to external disturbances [3]. |

| Loop [1] [6] | Redundant connections between branches within the same core area. | Indicates alternative pathways for ecological flows within a single habitat patch, potentially enhancing resilience and connectivity within complex core areas [1]. |

| Bridge [1] [3] | Foreground pixels that connect two or more disjoint core areas. | Functions as critical ecological corridors, facilitating the movement of organisms and the flow of ecological processes between different core habitats. These are priority areas for conservation to maintain landscape connectivity [3]. |

| Branch [1] [6] | Connectors that link core areas, edges, or bridges to isolated foreground pixels like islets. | Serves as a connecting pathway to smaller or more isolated habitat elements. While less robust than bridges, they can still facilitate ecological flows to peripheral areas [1]. |

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships and spatial configuration of the seven MSPA classes within a conceptual landscape.

Quantitative Data and MSPA Parameters

MSPA Output Classifications

While the landscape is initially divided into the seven basic classes, the full MSPA segmentation provides a more detailed classification. The following table summarizes the quantitative output of a typical MSPA analysis, showing the area and proportion of the landscape occupied by each class based on an example provided in the search results.

Table 2: Example quantitative output from an MSPA analysis, showing the area and proportion for each class [9].

| MSPA Class | Sub-class or Example | % of Foreground Area | % of Total Data Pixels | Number of Patches |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Core | Medium (m) | 75.09% | 32.19% | 1196 |

| Islet | - | 3.26% | 1.40% | 2429 |

| Perforation | - | 2.17% | 0.93% | 423 |

| Edge | - | 13.54% | 5.80% | 890 |

| Loop | - | 0.60% | 0.26% | 541 |

| Bridge | - | 1.42% | 0.61% | 765 |

| Branch | - | 3.93% | 1.68% | 4685 |

| Background | External | - | 57.14% | 2319 |

| Opening (Porosity) | - | 1.50% | 2291 | |

| Missing Data | - | - | 0.03% | 51 |

Key MSPA Parameters

The MSPA analysis is controlled by four key parameters that allow users to fine-tune the results to their specific research context and scale. The default values are commonly used, but adjustment is recommended based on the research question and data resolution [1] [9].

Table 3: Key parameters for configuring an MSPA analysis in software such as GuidosToolbox [1] [9].

| Parameter | Options | Default | Ecological Interpretation & Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Foreground Connectivity [1] | 4- or 8-connectivity | 8 | Defines pixel connectivity. 8-connectivity is standard for simulating unrestricted movement; 4-connectivity may be used for more restricted movement. |

| Edge Width [1] | Integer ≥ 1 | 1 | Determines the width (in pixels) of the Edge class. Increasing this value expands the edge zone at the expense of the Core area, directly influencing the perceived fragmentation. |

| Transition [1] | 0 (off) or 1 (on) | 1 | Controls whether Loop or Bridge pixels that traverse an edge or perforation are shown (1) or hidden (0). Affects the visual continuity of class perimeters. |

| IntExt [1] | 0 (off) or 1 (on) | 1 | When active (1), further classifies the internal background (perforations) into sub-classes like Core-Opening and Border-Opening, adding detail to the analysis of internal holes. |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

General MSPA Workflow for Ecological Applications

The following diagram outlines the standard end-to-end workflow for applying MSPA in an ecological research context, from data preparation to the application of results.

Protocol: Integrating MSPA with Circuit Theory for Ecological Network Conservation

This protocol details a specific application of MSPA, combining it with Circuit Theory to identify the spatial range of Ecological Networks (ENs) and priority areas for conservation, as demonstrated in a study on the Shandong Peninsula urban agglomeration [10].

Objective: To construct a spatially explicit ecological network by identifying ecological sources via MSPA and simulating ecological flows with Circuit Theory to delineate corridors, pinch points, and barriers [10].

Materials and Reagents:

- Software: GIS software (e.g., ArcGIS, QGIS), GuidosToolbox (GTB) or GuidosToolbox Workbench (GWB) for MSPA, and tools for Circuit Theory analysis (e.g., Circuitscape) [1] [9] [10].

- Data: Land Use/Land Cover (LULC) map of the study area.

Procedure:

- Data Preparation and MSPA Analysis:

- Reclassify the LULC map into a binary raster. Define the habitat of interest (e.g., forest, wetland) as the foreground (value 2) and all other classes as the background (value 1) [1] [10].

- Input the binary raster into GuidosToolbox. Set the MSPA parameters (e.g., Connectivity=8, EdgeWidth=1) based on the target species or ecological process [1] [9].

- Execute the MSPA analysis. The output will be a raster map where each pixel is assigned to one of the seven MSPA classes.

Identification of Ecological Sources:

Construction of Ecological Resistance Surface:

- Construct a resistance surface based on a habitat risk assessment. This surface assigns a cost value to every cell in the landscape, representing the perceived resistance to species movement. Lower values represent more permeable landscapes [10].

- The resistance surface can be calibrated using factors such as land use type, nighttime light intensity (as a proxy for human activity), and impervious surface area [10].

Simulation with Circuit Theory:

- Input the identified ecological sources (from Step 2) and the resistance surface (from Step 3) into a Circuit Theory model (e.g., Circuitscape) [10].

- The model simulates ecological flows as electrical current, calculating a cumulative current value across the landscape. Areas with high cumulative current values represent probable movement pathways and are identified as ecological corridors [10].

- Within these corridors, pinch points (areas where current is concentrated, indicating critical connectivity areas) and barriers (areas with low current flow, indicating blocked connectivity) are identified [10].

Delineation of the Ecological Network and Priority Areas:

- The spatial range of the ecological corridors is determined based on the spatial extent of the effective cumulative current values [10].

- Pinch points are designated as priority areas for conservation, as their loss would disproportionately disrupt connectivity.

- Barriers are designated as priority areas for restoration, where measures to reduce resistance (e.g., creating green passages) can restore ecological flows [10].

Table 4: Essential software, data, and analytical models used in MSPA-based ecological research.

| Tool / Resource | Type | Function & Application in MSPA Research |

|---|---|---|

| GuidosToolbox (GTB) / GWB [1] [9] | Software | The primary software packages providing the MSPA application. They are free to use and include MSPA along with many other spatial analysis tools. |

| GIS Software (e.g., ArcGIS, QGIS) [3] | Software | Used for pre-processing input data (creating binary masks), post-processing, and visualizing MSPA results. A QGIS plugin for MSPA is available, though with limited features compared to GTB [1]. |

| Binary Foreground/Background Mask [1] | Data | The fundamental input for MSPA. The researcher (expert) defines what constitutes the foreground (e.g., forest, wetland, green space) based on the research question, typically derived from land cover data. |

| Land Use/Land Cover (LULC) Data [10] [3] | Data | The most common base data used to create the binary mask for MSPA analysis in ecological studies. Resolution and classification accuracy are critical. |

| Circuit Theory Model (e.g., Circuitscape) [10] | Analytical Model | Used in conjunction with MSPA to simulate ecological flows and identify key connectivity areas (corridors, pinch points) based on resistance surfaces. |

| Minimum Cumulative Resistance (MCR) Model [11] [3] | Analytical Model | A common model integrated with MSPA to extract potential ecological corridors and construct ecological networks by calculating the least-cost path for ecological flows across a resistance surface. |

Application Notes: Quantifying Core Areas via MSPA

Quantitative Analysis of Ecological Source Dynamics

Morphological Spatial Pattern Analysis (MSPA) serves as a pivotal methodology for systematically identifying and classifying the spatial patterns of ecological landscapes, with core areas representing the most stable and vital foundational sources within an ecological network [12]. The following table synthesizes quantitative findings from empirical studies that employed MSPA to monitor the spatiotemporal evolution of these core areas.

Table 1: Quantitative Dynamics of Ecological Core Areas and Corridors Derived from MSPA

| Study Area / Period | Core Area Extent & Change | Number of Primary Corridors | Key Spatial Distribution Trends | Implications for Ecological Stability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ningbo City, China (2000-2020) [12] | Exhibited an uneven distribution, primarily located in western, southern, and coastal Hangzhou Bay regions. | Underwent a significant reduction from 26 (in 2000) to 17 (in 2020). | Primary corridors concentrated in central, southern, and western regions in 2000; by 2020, distribution shifted mainly southerly. | The reduction and shift weakened species spread and ecosystem stability, particularly reducing north-south ecological interaction. |

| Central Beijing, China [13] | Integrated evaluation using InVEST and MSPA to determine the importance of ecological sources. | Information was used to construct an Ecological Security Pattern (ESP) using circuit theory. | The study provided an integrated framework for evaluating ecological security patterns in urban centers. | The pattern is crucial for protecting biodiversity and maintaining regional sustainable development. |

Functional Interpretation of MSPA Outcomes

The quantitative data presented in Table 1 underscores the critical role of core areas as the foundation of ecological networks. The significant reduction in primary ecological corridors in Ningbo City over two decades highlights the pervasive impact of landscape fragmentation, often driven by large-scale changes in land use and increasing complexity of patches [12]. The consequent weakening of interaction between ecological sources, as observed in the north-south dynamic, directly and adversely impacts species dispersal and the overall stability of the ecosystem [12]. Constructing and maintaining robust ecological networks through the identification and protection of core areas is therefore vital for improving landscape connectivity, protecting biodiversity, and ensuring regional sustainable development [12].

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Methodology for MSPA-Based Ecological Network Construction

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for identifying core areas as foundational ecological sources and constructing ecological networks using MSPA, based on established research practices [12] [13].

Protocol Title: Delineation of Ecological Security Patterns through Morphological Spatial Pattern Analysis (MSPA) and Corridor Modeling.

Objective: To systematically identify core ecological areas, model connectivity corridors, and pinpoint strategic locations for ecological restoration to enhance network stability.

Pre-Experimental Requirements:

- Expertise: Proficiency in Geographic Information Systems (GIS), landscape ecology principles, and the operation of specific software (e.g., GuidosToolbox for MSPA, Linkage Mapper).

- Data Sources: Securely obtain land use/land cover (LULC) raster data for the study area for at least two distinct time periods to assess spatiotemporal change.

- Instruments & Software:

- GIS Software (e.g., ArcGIS, QGIS).

- GuidosToolbox software for performing MSPA classification.

- Linkage Mapper, an ArcGIS toolbox for corridor design.

Safety and Ethical Considerations: Ensure all spatial data used is properly licensed for research purposes. Respect data privacy and usage agreements when handling geographical information.

Procedure:

- Data Preparation and Land Use Classification:

- Acquire LULC raster data and reclassify it to create a binary landscape mask (e.g., foreground vs. background). The foreground typically represents natural ecological land covers (e.g., forest, grassland, wetlands), while the background represents other land uses (e.g., urban, agriculture).

MSPA Execution and Core Area Identification:

- Input the binary landscape mask into the GuidosToolbox software.

- Execute the MSPA function using established parameters and structural element sizes relevant to the study scale.

- The MSPA output will classify the landscape into seven morphological types: Core, Islet, Perforation, Edge, Loop, Bridge, and Branch.

- Extract the "Core" pixels from the MSPA result. These contiguous interior pixels of the foreground patches constitute the preliminary ecological sources.

Refinement of Ecological Sources:

- Evaluate the preliminary core areas based on additional factors such as patch size, ecological importance (e.g., using the InVEST model's habitat quality output), or connectivity importance [13].

- Select the most significant and stable core areas to serve as the final "ecological sources" for corridor modeling.

Corridor Modeling and Network Construction:

- Utilize the Linkage Mapper toolbox within ArcGIS.

- Input the refined ecological sources map.

- Model the least-cost paths or circuit-theory-based corridors between the ecological sources. This identifies the "primary ecological corridors."

Network Optimization and Breakpoint Identification:

- Analyze the modeled corridors to locate "ecological breakpoints"—specific areas where the corridor is narrowest or most vulnerable to disruption.

- Propose locations for "ecological nodes" (e.g., protected stepping stones) and additional "stepping stone patches" to reinforce connectivity at these breakpoints [12].

Troubleshooting:

- Issue: MSPA results show excessive fragmentation.

- Solution: Review the initial binary classification of the LULC data; adjust the classification scheme to ensure it accurately reflects functional ecological land.

- Issue: Modeled corridors are unrealistically straight or do not align with known landscape features.

- Solution: Refine the cost-surface layer used in Linkage Mapper to better represent resistance to species movement across different land cover types.

Reporting Standards: The experimental report must include the original LULC maps, the binary mask used for MSPA, the full MSPA classification result, maps of the final ecological sources and modeled corridors, and a table summarizing the number, area, and distribution of core areas and corridors over time [14].

Workflow Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Computational Tools and Data for MSPA-Based Ecological Research

| Item Name | Function / Application in MSPA Ecology |

|---|---|

| Land Use/Land Cover (LULC) Data | The fundamental input raster data for performing MSPA classification; defines the ecological foreground and non-ecological background of the study landscape [12]. |

| GuidosToolbox | The primary software application used to run the MSPA, which classifies the input landscape into core, edge, bridge, and other morphological classes [12]. |

| Linkage Mapper | A GIS software toolbox that uses least-cost path or circuit theory principles to model ecological corridors between the core areas identified by MSPA [12]. |

| InVEST Model | A suite of software models used to map and value ecosystem services; often integrated with MSPA to assess habitat quality and refine the selection of core ecological sources [13]. |

| Circuit Theory Models | A theoretical framework and associated tools (e.g., Circuitscape) applied to model landscape connectivity, treating the landscape as an electrical circuit to predict movement and identify pinch points [13]. |

MSPA's Application in Assessing Habitat Fragmentation and Connectivity

Morphological Spatial Pattern Analysis (MSPA) represents a significant advancement in the quantitative analysis of landscape patterns for ecological research. Unlike traditional landscape metrics, MSPA applies mathematical morphology principles to raster land cover data, enabling the automatic classification of landscape structures into distinct spatial pattern classes relevant to ecological function [3]. This method provides a precise, objective framework for identifying habitats critical to maintaining landscape connectivity and assessing the impacts of habitat fragmentation—a process identified as one of the most important causes of biodiversity loss [15]. The technique has evolved into an essential component of ecological network construction, particularly when integrated with functional connectivity models like circuit theory and minimum cumulative resistance (MCR) [16] [10].

The fundamental strength of MSPA lies in its ability to dissect landscape structure into seven mutually exclusive spatial classes based on pixel-level connectivity and morphological operations. This classification provides critical insights into structural connectivity—the physical arrangement of habitat elements—which serves as a foundation for assessing functional connectivity that governs ecological flows and species movement [17]. When applied within ecological security pattern (ESP) frameworks, MSPA enables researchers to systematically identify core habitat areas, stepping stones, and potential corridors that maintain ecological processes across fragmented landscapes [16] [18].

Core MSPA Methodology and Classification

MSPA Spatial Pattern Classes

MSPA classifies each foreground pixel (typically representing habitat or vegetation) into one of seven distinct spatial categories based on its morphological position and connectivity:

Table 1: MSPA Spatial Pattern Classification and Ecological Significance

| MSPA Class | Morphological Definition | Ecological Function | Conservation Priority |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core | Interior habitat areas surrounded by similar habitat | Provides critical habitat for sensitive species, maintains ecosystem processes | Highest - primary ecological sources |

| Edge | Habitat perimeter adjacent to different land cover | Experienced edge effects, modified microclimate | Moderate - requires buffer management |

| Bridge | Connecting elements between core areas | Facilitates landscape connectivity and species movement | High - crucial for maintaining meta-populations |

| Loop | Alternative connections between core areas | Provides redundant pathways, enhancing network resilience | Moderate-High - maintains connectivity alternatives |

| Islet | Small, isolated habitat patches | May serve as temporary habitat or stepping stones | Variable - context dependent |

| Perforation | Internal boundaries within core areas | Creates habitat heterogeneity but reduces core area | Low-Moderate - management may be required |

| Branch | Dead-end connections from core areas | Limited connectivity value, potential ecological traps | Low - limited functional significance |

These structural classifications enable researchers to move beyond simple habitat area measurements to understand the spatial configuration of habitats and its implications for ecological processes [3] [17]. Core areas identified through MSPA typically serve as ecological sources in network construction, while bridges and loops form the structural basis for potential corridors [16] [10].

Technical Workflow for MSPA Implementation

The standard MSPA implementation follows a structured analytical workflow that transforms land cover data into ecologically meaningful spatial patterns:

Data Preparation and Processing Steps:

- Land Cover Classification: Begin with high-resolution land use/land cover (LULC) data derived from satellite imagery (e.g., Landsat, Sentinel) or aerial photography. The classification should accurately distinguish between habitat (foreground) and non-habitat (background) areas [16] [19].

- Binary Mask Creation: Convert the land cover data into a binary raster where habitat classes of interest (e.g., forests, natural vegetation) are designated as foreground (value = 1) and all other classes as background (value = 0) [3] [15].

- MSPA Parameterization: Process the binary map using specialized software (typically GuidosToolbox) with appropriate structuring element size (usually 8-pixel connectivity) and edge width parameters tailored to the study organisms and landscape scale [17] [15].

- Connectivity Assessment: Calculate landscape connectivity indices (e.g., probability of connectivity, integral index of connectivity) for core areas to evaluate their functional importance within the landscape network [16] [10].

- Ecological Source Identification: Select the most significant core areas based on size, connectivity value, and ecological context to serve as primary sources in subsequent ecological network modeling [3] [18].

Quantitative Applications in Habitat Fragmentation Assessment

Case Study Applications and Metrics

MSPA has been successfully applied across diverse ecosystems to quantify fragmentation patterns and identify conservation priorities. The following table synthesizes key quantitative findings from recent applications:

Table 2: MSPA Application Across Ecosystem Types and Key Findings

| Ecosystem/Region | Study Focus | Key MSPA Metrics | Fragmentation Findings | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| South China Karst | Desertification control forests | Core area percentage, fragmentation index | Severe fragmentation with patch area significantly decreasing as karst desertification severity increases | [16] |

| Çankırı Forest, Turkey | Forest habitat connectivity | Component connection, network analysis | Forest area increased by 23% over 30 years, but fragmentation persisted due to uncoordinated afforestation | [15] |

| Shandong Peninsula Urban Agglomeration | Ecological network construction | Core area distribution, corridor connectivity | Identified 6,263.73 km² ecological sources and 12,136.61 km² corridors with specific pinch points (283.61 km²) | [10] |

| Taihu Lake Basin, China | Cross-regional ecological security | Structural connectivity, corridor nodes | Pattern included 20 ecological sources, 37 corridors, 36 protection nodes, and 24 restoration nodes | [18] |

| Shenzhen City, China | Urban ecological networks | Core area importance, corridor width | Optimal ecological corridor width identified between 60-200 meters for urban biodiversity | [3] |

Fragmentation Indices and Landscape Metrics

When integrated with complementary landscape analysis tools, MSPA generates quantitative indicators of habitat fragmentation:

- Patch Size Distribution: MSPA analysis in South China Karst revealed that core forest areas decreased substantially with increasing karst desertification intensity, demonstrating how environmental degradation directly fragments habitats [16].

- Structural Connectivity Metrics: Applications in Turkey's Çankırı forest ecosystem utilized MSPA with network analysis to test corridor creation between fragmented forest patches, identifying opportunities to improve connections through targeted restoration [15].

- Edge Effect Quantification: Urban studies in Shenzhen employed MSPA to quantify edge habitats and determine optimal ecological corridor widths of 60-200 meters for maintaining urban biodiversity [3].

The combination of MSPA with graph-based connectivity indices enables a comprehensive assessment of both the structural patterns and functional implications of habitat fragmentation, providing robust scientific support for conservation planning [17].

Integration with Ecological Connectivity Models

MSPA-Circuit Theory Framework

The integration of MSPA with circuit theory represents a powerful methodological advancement for modeling ecological connectivity. This combined approach leverages the structural identification capabilities of MSPA with the functional movement simulation of circuit theory:

This integrated framework addresses a critical limitation of traditional MSPA by incorporating functional connectivity - how landscapes actually facilitate or impede species movement based on resistance features [10] [18]. Circuit theory simulates ecological flows as electrical current moving through a resistant landscape, identifying:

- Pinch Points: Areas where movement channels are constricted (high current density)

- Barriers: Areas that strongly impede connectivity (low current flow)

- Alternative Routes: Multiple potential pathways for ecological flows [10]

MSPA-MCR Model Integration

Similarly, the combination of MSPA with the Minimum Cumulative Resistance (MCR) model enhances ecological network construction:

- MSPA provides objectively identified ecological sources based on structural connectivity and landscape metrics, overcoming the subjective source selection that often plagues MCR applications [3].

- MCR then calculates the accumulated cost for species movement between these sources, identifying optimal corridor routes while considering landscape resistance [3].

This coupling was effectively demonstrated in Shenzhen City, where researchers extracted ten core areas based on MSPA and landscape metrics, then used MCR to construct corridors which were further optimized with stepping stones (35 locations) and ecological fault points (17 locations) [3]. The resulting network included classified corridors (11 important, 34 general, and 7 potential) with specified width parameters for urban conservation planning.

Application Notes and Experimental Protocols

Standard Protocol for MSPA-Based Fragmentation Assessment

Objective: To quantify habitat fragmentation patterns and identify core ecological areas for conservation planning using MSPA.

Materials and Software Requirements: Table 3: Essential Research Tools and Resources for MSPA Analysis

| Category | Specific Tools/Data | Purpose/Function | Data Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Remote Sensing Data | Landsat 8/9, Sentinel-2 | Land cover classification | USGS EarthExplorer, ESA Copernicus |

| GIS Software | ArcGIS, QGIS | Spatial data processing and analysis | Commercial/Open Source |

| MSPA Software | GuidosToolbox | Morphological spatial pattern analysis | European Commission JRC |

| Connectivity Analysis | Conefor, Linkage Mapper | Graph-based connectivity metrics | Open source conservation tools |

| Validation Data | Field surveys, species occurrence records | Ground truthing of habitat models | Field collection, GBIF |

Methodological Steps:

Land Cover Classification and Validation

- Acquire recent satellite imagery appropriate for the study scale (e.g., 10-30m resolution for regional assessments)

- Perform supervised classification using ground-truthed training data to create a land cover map

- Validate classification accuracy with independent reference data (minimum 80% accuracy recommended)

Binary Habitat Mask Creation

- Reclassify the land cover map to distinguish habitat (foreground) from non-habitat (background) classes based on study objectives

- Consider creating multiple scenarios for different habitat definitions or species groups

- Export as a binary raster with 1 (habitat) and 0 (non-habitat) values

MSPA Parameterization and Execution

- Process the binary raster in GuidosToolbox using the MSPA function

- Set the edge width parameter based on the study organisms (e.g., 100m for forest interior species)

- Use 8-pixel connectivity to identify the seven MSPA classes

- Export results as classified MSPA raster and calculate area statistics for each class

Connectivity Analysis and Ecological Source Identification

- Calculate connectivity indices (e.g., probability of connectivity) for core areas using Conefor or similar tools

- Select core areas above specific thresholds (size, connectivity value) as ecological sources

- Generate maps showing the spatial distribution of high-priority core areas and connecting elements

Integration with Functional Connectivity Models

- Develop an ecological resistance surface incorporating land use, topography, and human impact factors

- Apply circuit theory or MCR models to identify corridors and key nodes between ecological sources

- Validate model predictions with field data on species occurrence or movement where available

Specialized Protocol for Urban Ecological Networks

Objective: To construct and optimize ecological networks in urban landscapes using MSPA and circuit theory.

Methodological Adaptation:

- Urban-Specific Resistance Factors: Incorporate urban-specific resistance features including road density, nighttime light intensity, impervious surface percentage, and human population density [3] [10].

- Corridor Width Optimization: Determine appropriate ecological corridor widths based on urban constraints and species requirements (typically 60-200m as identified in Shenzhen) [3].

- Stepping Stone Integration: Identify small urban habitat patches (islets) that can function as stepping stones for species movement between larger core areas [3].

Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools for MSPA-Based Fragmentation Analysis

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Application Context | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| GuidosToolbox | MSPA implementation and basic fragmentation metrics | Core MSPA processing, structural pattern classification | Free, JRC |

| Conefor Sensinode | Graph-based connectivity analysis | Calculating connectivity indices for core areas | Free, standalone |

| Linkage Mapper | Corridor and ecological network modeling | Designing connectivity corridors between core habitats | Free, GIS toolbox |

| Circuitscape | Circuit theory-based connectivity modeling | Identifying pinch points, barriers, and movement pathways | Free, standalone |

| FRAGSTATS | Comprehensive landscape metrics | Complementary landscape pattern analysis | Free, standalone |

These tools collectively provide a comprehensive analytical toolkit for implementing the complete MSPA-connectivity analysis workflow, from initial habitat pattern assessment to functional ecological network design.

Essential Data Requirements and Preprocessing for Effective MSPA

Morphological Spatial Pattern Analysis (MSPA) is a specialized image processing methodology that applies a customized sequence of mathematical morphological operators to describe the geometry and connectivity of image components [1]. Originally developed for general pattern recognition, MSPA has become an invaluable tool in landscape ecology for analyzing spatial patterns of ecological features. The method operates on binary images (foreground/background) and classifies the foreground into seven mutually exclusive pattern classes: Core, Islet, Perforation, Edge, Loop, Bridge, and Branch [1]. This classification enables researchers to quantify critical landscape characteristics that influence ecological processes, biodiversity, and ecosystem functionality.

The fundamental value of MSPA in ecological research lies in its ability to objectively identify and measure structural components of landscapes that serve essential ecological functions. Core areas represent the interior habitats essential for specialist species, while bridges and loops function as ecological corridors that facilitate wildlife movement and genetic flow [1]. Edges represent transition zones between different habitat types, and perforations indicate gaps within otherwise continuous habitat patches. This structural information is crucial for understanding functional connectivity across landscapes and forms the basis for designing effective ecological networks and conservation strategies.

Data Requirements for MSPA

Input Data Specifications

Successful application of MSPA in ecological research requires careful preparation of input data that accurately represents the ecological features of interest. The primary input for MSPA is a binary raster map where pixel values distinctly separate foreground (features of ecological relevance) from background (all other areas) [1]. This binary representation forms the foundation for all subsequent pattern analysis and classification.

Table 1: Essential Data Requirements for MSPA Implementation

| Requirement Category | Specification | Ecological Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| Input Format | Binary raster (foreground/background) | Enables clear distinction between habitat and non-habitat areas |

| Spatial Resolution | Appropriate to ecological processes studied; typically 10-30m for regional studies [20] | Determines detectable detail and minimum patch size |

| Thematic Accuracy | Correct classification of ecological features as foreground | Ensures analysis reflects actual habitat distribution |

| Spatial Extent | Must encompass complete ecological units or landscapes | Prevents edge effects and ensures meaningful connectivity analysis |

| Coordinate System | Projected coordinate system preserving distance and area | Maintains geometric accuracy for spatial measurements |

The binary input mask must be derived from land cover classification or habitat mapping data that accurately identifies the ecological features of interest. For forest ecology applications, this would typically be a forest/non-forest mask [1], while for wetland studies, it would be a wetland/non-wetland classification. The choice of spatial resolution is critical, as it determines the minimum detectable feature size and influences the representation of habitat connectivity. Studies in urban ecological contexts, such as the Zhengzhou City analysis, have successfully utilized land use data with a resolution of 10m × 10m [20].

Data Preprocessing Workflow

The transformation of raw spatial data into a properly formatted binary mask for MSPA involves several critical preprocessing steps that ensure analytical accuracy and ecological relevance.

The preprocessing workflow begins with acquisition of raw spatial data, which may include satellite imagery, aerial photography, or existing land cover maps. For the Zhengzhou City study examining urban ecological sources, researchers obtained remote sensing images from platforms including Geospatial Data Cloud and the Natural Resources Satellite Remote Sensing Cloud Service Platform [20]. These images underwent visual interpretation using ArcGIS 10.8 software to generate land use data with 10m × 10m resolution, categorized into woodland, water, grassland, arable land, construction land, and unused land [20].

The classification step involves converting raw data into thematic categories relevant to the ecological research questions. This may employ automated classification algorithms, manual digitization, or a hybrid approach. The resulting thematic map then undergoes accuracy assessment using ground truth data, high-resolution imagery, or independent validation datasets to ensure reliable representation of ecological features. Following validation, the thematic map is converted to a binary mask by reclassifying all relevant ecological features as foreground (typically value 1) and all other areas as background (typically value 0). Finally, resolution standardization ensures the binary mask matches the intended analysis scale and is compatible with MSPA processing requirements.

MSPA Parameter Configuration

Critical Analysis Parameters

MSPA provides four key parameters that allow researchers to tailor the analysis to specific ecological contexts and research questions. Proper configuration of these parameters is essential for obtaining ecologically meaningful results that accurately reflect the spatial patterns and processes under investigation.

Table 2: MSPA Parameters and Their Ecological Interpretation

| Parameter | Technical Function | Ecological Significance | Recommended Settings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Foreground Connectivity | Defines pixel connectivity rule (4 or 8) | Determines how habitat patches are defined and connected | 8-connectivity for animal movement; 4-connectivity for plant dispersal |

| Edge Width | Sets the width of the edge zone (in pixels) | Defines transition zone depth between habitat interiors and matrix | Based on known edge effect distances for target species |

| Transition | Controls display of pixels connecting across edges | Highlights or suppresses corridors that cross habitat boundaries | Show transitions for connectivity analysis; hide for patch integrity assessment |

| Intext | Enables/disables internal texturing of perforations | Differentiates internal gaps from external background | Enable for detailed habitat fragmentation analysis |

The Foreground Connectivity parameter fundamentally influences how habitat patches are identified and connected. Using 8-connectivity (considering all adjacent pixels, including diagonals) typically results in more continuous habitat patterns, which may better represent movement potential for many wildlife species. In contrast, 4-connectivity (considering only orthogonally adjacent pixels) creates a more restrictive connectivity model that may be appropriate for species with limited dispersal capabilities or when analyzing habitat patterns for plants with specific dispersal mechanisms [1].

The Edge Width parameter directly controls the spatial extent of edge effects in the analysis. Increasing the Edge Width expands the non-core area at the expense of core habitat, potentially reclassifying some core pixels as edge [1]. This parameter should be calibrated based on empirical research about edge effect distances for the target ecosystem and species. For example, forest edge effects on microclimate and species composition may extend 50-100 meters into habitat patches, which would inform appropriate Edge Width settings when working with forest habitat masks.

MSPA Processing Workflow

The complete MSPA workflow integrates parameter configuration with the binary input data to generate the detailed pattern classification that facilitates ecological interpretation.

The MSPA algorithm processes the binary input map according to the specified parameters, systematically classifying each foreground pixel into one of the seven pattern classes. Core areas represent the interior regions of habitat patches that are not influenced by edge effects [1]. Islets are small, isolated habitat patches that lack core area due to their size. Perforations represent gaps within core areas, such as natural clearings or human-made openings within forested landscapes. Edge pixels form the boundary between core areas and the background matrix.

Connectivity elements include Bridges that connect different core areas, Loops that form redundant connections between core areas, and Branches that represent dead-end connections from core areas to other class types [1]. The identification and quantification of these connectivity elements is particularly valuable for understanding landscape permeability and designing ecological networks. In the Zhengzhou City study, MSPA was employed specifically to identify ecological sources across three different development scenarios, demonstrating its application in urban ecological planning [20].

Ecological Interpretation and Application

Interpreting MSPA Results in Ecological Context

The translation of MSPA structural classes into ecologically meaningful information requires careful consideration of the specific ecosystem and research objectives. Each MSPA class corresponds to distinct ecological functions that influence species distribution, population dynamics, and ecosystem processes.

Core areas typically represent the highest quality habitat for area-sensitive and interior-dependent species [1]. The spatial configuration and size distribution of core areas directly influences population viability for many specialist species. In the Zhengzhou urban ecology study, core forest patches identified through MSPA were considered primary ecological sources that exerted the strongest ecological effects on the urban environment [20]. The Largest Patch Index (LPI) of these ecological sources showed an upward trend in future scenarios, suggesting that large, contiguous patches would dominate ecological source expansion [20].

Connectivity elements (Bridges, Loops, and Branches) play crucial roles in maintaining functional connectivity across landscapes [1]. Bridges serve as essential corridors for wildlife movement and genetic exchange between core areas. The identification of these connecting structures enables conservation planners to prioritize protection of landscape elements that maintain ecological networks. MSPA has demonstrated capability in detecting connecting structures such as wildlife corridors and riparian connections, as illustrated by its application to water masks in Finland, where it successfully identified rivers connecting multiple lakes [1].

Integration with Ecological Models

MSPA classifications typically serve as input for further ecological analysis and modeling rather than as final products. The structural patterns identified through MSPA provide the foundation for assessing functional connectivity and modeling ecological processes across landscapes.

In comprehensive ecological assessments, MSPA is frequently integrated with additional analytical approaches to develop complete ecological security patterns. As demonstrated in research on Beijing's ecological security pattern, MSPA can be combined with the InVEST model and multifactor indices to provide a holistic evaluation of ecological network functionality [13]. Similarly, the Zhengzhou study integrated MSPA with the PLUS model to simulate future ecological source patterns under different development scenarios, including natural evolution, cropland protection, and ecological protection scenarios [20].

This integration of MSPA with predictive modeling approaches enables researchers and planners to evaluate potential impacts of future land use change on ecological networks and identify strategic priorities for conservation intervention. The combination of structural pattern analysis (MSPA) with functional assessment (InVEST) and scenario modeling (PLUS) provides a powerful framework for evidence-based landscape planning and conservation prioritization.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools and Software for MSPA Implementation

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Function in MSPA Research | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specialized Software | GuidosToolbox (GTB), GuidosToolbox Workbench (GWB) | Primary MSPA execution platform with complete feature set | Free download available |

| GIS Platforms | ArcGIS, QGIS | Data preprocessing, binary mask preparation, and result visualization | Commercial and open-source options |

| GIS Plugins | MSPA plugins for ArcGIS, QGIS3, and R | Limited MSPA functionality within host GIS environments | Available with documentation |

| Remote Sensing Data | Landsat, Sentinel, Aerial Imagery | Source data for binary mask creation | Various open access and commercial sources |

| Spatial Analysis Tools | R, Python with spatial libraries | Custom analysis and automation of MSPA workflows | Open source |

The GuidosToolbox (GTB) and GuidosToolbox Workbench (GWB) represent the primary software solutions for conducting MSPA analysis, as they include the complete MSPA implementation with full feature set [1]. These freely available tools provide access to all MSPA parameters and analytical capabilities. For researchers working within established GIS environments, MSPA plugins are available for ArcGIS, QGIS3, and R, though these may not provide the complete feature set available in the dedicated GTB/GWB software [1].

The preparation of binary input masks typically requires standard GIS software such as ArcGIS or QGIS for data preprocessing, classification, and format conversion. The Zhengzhou City study utilized ArcGIS 10.8 for visual interpretation of remote sensing imagery to generate land use data [20]. For advanced analytical workflows and automation, programming environments such as R and Python with specialized spatial libraries provide flexibility for customizing MSPA applications and integrating results with other ecological models.

Implementing MSPA: A Step-by-Step Guide from Analysis to Ecological Security Patterns

The identification of ecological sources is a foundational step in constructing ecological networks for biodiversity conservation and sustainable landscape planning. Ecological sources are habitat patches that are crucial for maintaining regional ecosystem functions, facilitating species movement, and ensuring ecological connectivity [10]. This protocol details a integrated methodology that combines Morphological Spatial Pattern Analysis (MSPA) with Habitat Quality Assessment to objectively identify and prioritize these critical ecological areas. This integrated approach addresses limitations of using either method alone by simultaneously evaluating structural connectivity through MSPA and functional ecological value through habitat quality assessment [21] [22]. The framework is particularly valuable in rapidly urbanizing regions where habitat fragmentation threatens ecological sustainability [10] [3].

MSPA provides a precise, mathematical methodology for segmenting and classifying landscape patterns based on geometric concepts applied to binary raster images [1]. When applied to ecological land types (e.g., forest, wetland), it automatically identifies seven distinct spatial pattern classes that differ in their ecological function and connectivity value [1]. Meanwhile, habitat quality assessment evaluates the condition and suitability of habitats to support species or ecological communities based on multiple environmental factors [23]. Combining these approaches ensures identified ecological sources possess both structural importance within the landscape mosaic and high functional ecological value.

Theoretical Framework and Integration Rationale

MSPA Fundamentals and Ecological Interpretation

MSPA operates on binary images (foreground/background) and classifies the foreground into seven mutually exclusive spatial pattern classes [1]. The ecological relevance of each class is as follows:

- Core: Interior habitat areas that provide essential shelter and breeding grounds for species sensitive to disturbance [1] [21]

- Bridge: Connecting pathways between core areas that facilitate landscape connectivity

- Edge: Transition zones between core and non-habitat areas, important for edge-tolerant species

- Loop: Alternative connecting pathways that provide redundancy in ecological networks

- Branch: Connectors that lead to dead ends, offering limited connectivity value

- Perforation: Internal boundaries within core areas created by small-scale disturbances

- Islet: Small, isolated patches that may serve as stepping stones but lack core area characteristics

The core areas identified through MSPA typically form the initial candidate pool for ecological sources due to their spatial characteristics and potential habitat functionality [21] [3]. Studies have shown that core areas often constitute the majority of ecological source areas, with one study reporting core areas representing 80.69% of all landscape types identified through MSPA [21].

Habitat Quality Assessment Components

Habitat quality assessment evaluates the capacity of an area to support sustainable populations of specific species or communities. Advanced assessment techniques incorporate:

- Remote sensing data from satellite imagery (e.g., Landsat, Sentinel) and drone-based surveys for habitat mapping and monitoring [23]

- Environmental variables including vegetation indices, land use intensity, proximity to human disturbances, and topographic factors [21]

- Machine learning algorithms such as Random Forest and Support Vector Machines for habitat quality prediction and classification [23]

Integration Benefits

The synergistic combination of MSPA and habitat quality assessment provides:

- Objectivity in source selection by reducing subjective judgment in identifying ecologically significant areas [3]

- Structural-functional complementarity by ensuring sources are both well-connected spatially and ecologically viable [22]

- Conservation efficiency by prioritizing areas that offer maximum ecological benefit for conservation investment [10]

- Multi-scale applicability with methods adaptable from local to regional scales [1]

Experimental Protocols

Data Preparation and Preprocessing

Table 1: Required Data Sources and Specifications

| Data Type | Spatial Resolution | Sources | Primary Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Land Use/Land Cover | 30 m or higher | Landsat 8 OLI/TIRS, Sentinel-2 | MSPA foreground definition, resistance surface |

| Digital Elevation Model (DEM) | 30 m | Geospatial Data Cloud | Topographic analysis, resistance factor |

| NDVI | 30 m | Derived from Landsat 8 | Vegetation health assessment |

| Road Networks | Vector | OpenStreetMap, national databases | Disturbance factor for resistance |

| Water Bodies | Vector/Raster | National hydrography datasets | Hydrological connectivity |

| Administrative Boundaries | Vector | National census agencies | Analysis unit definition |

Step 1: Land Cover Classification

- Acquire recent remote sensing imagery appropriate for your study area scale (e.g., Landsat 8 OLI/TIRS with 30m resolution for regional studies) [21]

- Perform supervised classification using software such as ENVI 5.3 or equivalent open-source alternatives

- Classify land cover into minimum categories: woodland, water body, grassland, cultivated land, construction land, and other land [21]

- Verify classification accuracy through field validation and confusion matrix analysis (target overall accuracy >85% with Kappa coefficient >0.8) [21]

Step 2: Binary Habitat/Non-habitat Mask Creation

- Reclassify land cover data into binary format based on ecological relevance to research objectives

- Assign value 2 to foreground (ecological habitats: typically forest, woodland, natural grasslands, wetlands) [21]

- Assign value 1 to background (non-habitat areas: typically urban, agricultural, other human-modified lands)

- Export as 8-bit GeoTIFF format for compatibility with MSPA analysis tools [21]

MSPA Analysis Protocol

Step 1: Software Setup and Parameter Configuration

- Utilize GuidosToolbox (GTB) or GuidosToolbox Workbench (GWB) software, which includes dedicated MSPA functions [1]

- Configure four critical MSPA parameters:

- Foreground Connectivity: 8-connectivity recommended for most ecological applications (diagonal movement allowed) [1]

- Edge Width: Set based on research scale and target species; typically 1-3 pixels (review effects in MSPA guide) [1]

- Transition: Set to 1 to maintain transition pixels between classes [1]

- Intext: Set to 1 to enable segmentation of internal background areas [1]

Step 2: MSPA Execution and Interpretation

- Run MSPA analysis on binary habitat mask

- Process output to identify core areas exceeding minimum patch size threshold (varies by study; e.g., 17 pixels as used in Qujing City study) [21]

- Extract all seven MSPA classes for comprehensive landscape pattern assessment

- Calculate area and spatial distribution of each MSPA class

Habitat Quality Assessment Protocol

Step 1: Assessment Factor Selection Select factors appropriate to your ecological context and data availability:

Table 2: Habitat Quality Assessment Factors

| Factor Category | Specific Metrics | Data Sources | Ecological Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Landscape Composition | NDVI, Land use intensity | Landsat imagery, classified land cover | Vegetation vigor, habitat suitability |

| Anthropogenic Pressure | Distance to roads, Distance to residential areas, Nighttime light intensity | Road networks, Settlement data, VIIRS DNB | Disturbance intensity, human footprint |

| Topographic Features | Elevation, Slope | DEM derivatives | Environmental filtering, species preferences |

| Hydrological Influence | Distance to water bodies | National hydrography datasets | Riparian connectivity, moisture gradients |

Step 2: Habitat Quality Modeling

- Apply the InVEST Habitat Quality model or similar habitat assessment tools

- Alternatively, employ machine learning algorithms (Random Forest, SVM) for habitat classification and quality prediction [23]

- Normalize all factors to a consistent scale (e.g., 0-1 or 0-100)

- Validate model outputs with field observations or species occurrence data when available

Integrated Ecological Source Identification

Step 1: Preliminary Source Selection

- Extract core areas from MSPA results as candidate ecological sources [21]

- Overlay habitat quality assessment results to identify high-quality patches

- Establish minimum quality thresholds based on habitat assessment scores

- Select patches meeting both structural (core area) and functional (quality) criteria

Step 2: Connectivity Analysis

- Calculate landscape connectivity indices for candidate patches:

- Compute importance value of patches (dPC) to quantify contribution to overall connectivity [21]: Where PC_remove is connectivity after removing patch i

Step 3: Final Ecological Source Designation

- Apply threshold criteria for patch area, habitat quality, and connectivity importance

- Select patches that exceed all established thresholds as final ecological sources

- Document selection rationale and thresholds for reproducibility

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Integrated MSPA-Habitat Assessment Workflow

Diagram 2: MSPA Classification Logic

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Tools and Platforms

| Tool/Platform | Primary Function | Access | Application in Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|

| GuidosToolbox (GTB) | MSPA analysis | Free download | Core spatial pattern analysis [1] |

| ArcGIS | Geospatial analysis | Commercial license | Data preprocessing, overlay analysis, cartography |

| QGIS | Geospatial analysis | Open source | Alternative to ArcGIS for spatial operations |

| InVEST Habitat Quality | Habitat assessment | Free download | Standardized habitat quality modeling |

| R Statistics | Connectivity analysis | Open source | Landscape connectivity metrics calculation |

| Google Earth Engine | Remote sensing processing | Cloud platform | Land cover classification, NDVI calculation |

| FragStats | Landscape metrics | Free download | Additional landscape pattern analysis |

Data Presentation and Analysis

MSPA Results Quantification

Table 4: Example MSPA Class Distribution from Qujing City Study [21]

| MSPA Class | Area (km²) | Percentage of Total Foreground | Ecological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Area | 125.42 | 80.69% | Primary ecological source candidate |

| Edge | 15.89 | 10.22% | Transition zone, edge habitat |

| Bridge | 8.76 | 5.64% | Connectivity elements |

| Loop | 2.45 | 1.58% | Alternative pathways |

| Branch | 1.23 | 0.79% | Limited connectivity value |

| Perforation | 0.87 | 0.56% | Internal disturbances |

| Islet | 0.64 | 0.41% | Potential stepping stones |

| Total Foreground | 155.26 | 100% |

Habitat Quality and Connectivity Metrics

Table 5: Ecological Source Selection Criteria from Case Studies

| Selection Criterion | Qujing City [21] | Shandong Peninsula [10] | Shenzhen City [3] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum Core Area | 17 pixels | Not specified | Maximum importance patch values |

| Habitat Quality Factors | Land use, DEM, slope, NDVI | Habitat risk assessment | Landscape index method |

| Connectivity Threshold | dPC value ranking | Cumulative current value | Patch importance value |

| Number of Selected Sources | 14 | Not specified | 10 |

| Percentage of Study Area | Not specified | 8.55% of total area | Not specified |

Application Notes and Troubleshooting

Scale Considerations

- Regional studies (>1,000 km²): Use moderate resolution data (30m) with edge width of 2-3 pixels

- Local studies (<1,000 km²): Use high-resolution data (<10m) with edge width of 1-2 pixels

- Adjust minimum core area threshold based on study extent and target species requirements

Parameter Sensitivity

- Test multiple edge width values and assess impact on core area identification [1]

- Evaluate different habitat quality factor weightings through sensitivity analysis

- Validate MSPA connectivity designations with field observations of species movement

Common Challenges and Solutions

- Challenge: Discrepancy between structural connectivity (MSPA) and functional connectivity (species-specific movement)

- Solution: Incorporate species occurrence data to validate corridor functionality

- Challenge: Computational limitations with high-resolution data over large areas

- Solution: Implement analysis in Google Earth Engine or use tiled processing approaches

- Challenge: Determining appropriate thresholds for habitat quality

- Solution: Use statistical approaches (e.g., natural breaks, standard deviations) or expert consultation

This integrated protocol provides a robust, reproducible methodology for identifying ecological sources that are both structurally significant and functionally viable, forming a critical foundation for ecological network planning and biodiversity conservation in fragmented landscapes.

Coupling MSPA with Circuit Theory to Model Ecological Flows and Corridors

The accelerating pace of landscape fragmentation due to urbanization and land use changes has triggered significant habitat loss and ecosystem degradation, posing substantial threats to regional ecological sustainability and biodiversity [10] [18]. In response, ecological security patterns (ESP) have emerged as crucial spatial regulation schemes that coordinate natural ecosystems with socio-economic systems [10]. Constructing effective ESP requires robust methodologies to identify ecologically significant areas and model the functional connectivity between them.

This protocol details the integration of Morphological Spatial Pattern Analysis (MSPA) with Circuit Theory to address critical limitations in conventional ecological network modeling. While MSPA excels at identifying structurally connected habitats based on landscape pattern morphology [24] [18], Circuit Theory effectively models the functional connectivity and species movement probabilities across heterogeneous landscapes [10] [18]. This powerful combination enables researchers to not only identify ecological corridors but also determine their specific spatial ranges, key nodes, and priority areas for conservation and restoration [10].

Theoretical Framework and Integration Rationale

Complementary Methodological Strengths

The integration of MSPA and Circuit Theory creates a synergistic framework that overcomes the limitations of each method when used in isolation:

MSPA provides a precise, mathematical characterization of landscape structure based on raster geometry and connectivity, automatically classifying each pixel into distinct morphological classes (e.g., cores, bridges, loops) [24]. This structural analysis identifies potential ecological sources based on physical configuration but does not explicitly model species movement or functional connectivity.

Circuit Theory models landscape connectivity by analogizing ecological networks as electrical circuits, where species movement represents current flow, habitats represent nodes, and the landscape matrix represents resistors [10] [18]. This approach accommodates the stochastic wandering behavior of species and identifies pinch points and barriers - critical areas that significantly influence connectivity.

Key Advantages Over Traditional Approaches

Traditional approaches like the Minimum Cumulative Resistance (MCR) model can determine corridor direction and optimal routes but cannot clarify the spatial extent of corridors or identify key nodes within them [10]. The MSPA-Circuit Theory coupling addresses these limitations by:

- Objectively identifying ecological sources based on structural connectivity rather than expert opinion [18]

- Simulating multiple potential movement pathways rather than single optimal routes [10]

- Quantifying corridor widths and specific spatial boundaries based on cumulative current flow [10]

- Pinpointing precise locations for conservation priority areas (pinch points) and restoration needs (barriers) [18]

Data Requirements and Preparation

Core Data Types and Specifications