Many-Core Parallelism in Ecology: Accelerating Discovery from Populations to Molecules

The surge of massive datasets and complex models in ecology has created a pressing need for advanced computational power.

Many-Core Parallelism in Ecology: Accelerating Discovery from Populations to Molecules

Abstract

The surge of massive datasets and complex models in ecology has created a pressing need for advanced computational power. This article explores the transformative role of many-core parallelism in overcoming these computational barriers. We first establish the foundational principles of parallel computing and its alignment with modern ecological challenges, such as handling large-scale environmental data and complex simulations. The discussion then progresses to methodological implementations, showcasing specific applications in population dynamics, spatial capture-recapture, and phylogenetic inference. A dedicated troubleshooting section provides practical guidance on overcoming common hurdles like load balancing and memory management. Finally, we present rigorous validation through case studies demonstrating speedups of over two orders of magnitude, concluding with the profound implications of these computational advances for predictive ecology, conservation, and biomedical research.

The Computational Imperative: Why Ecology Needs Many-Core Power

The field of ecology is undergoing a profound transformation, driven by technological advancements that generate data at unprecedented scales and resolutions. From high-throughput genomic sequencers producing terabyte-scale datasets to satellite remote sensing platforms capturing continental-scale environmental patterns, ecological research now faces a data deluge that threatens to overwhelm traditional analytical approaches [1]. This exponential growth in data volume, velocity, and variety necessitates a paradigm shift in how ecologists collect, process, analyze, and interpret environmental information. The challenges are particularly acute in domains such as genomics, where experiments now regularly process petabytes of data, and large-scale ecological mapping, where spatial validation issues can lead to dramatically overoptimistic assessments of model predictive power [1] [2].

Within this context, many-core parallelism has emerged as a critical enabling technology for ecological research. By distributing computational workloads across hundreds or thousands of processing cores, researchers can achieve orders-of-magnitude improvements in processing speed for tasks ranging from genome sequence alignment to spatial ecosystem modeling. The advantage of many-core architectures lies not merely in accelerated computation but in enabling analyses that were previously computationally infeasible, such as comparing thousands of whole genomes or modeling complex ecological interactions across vast spatial extents [1]. This technical guide explores the parallel computing strategies and infrastructures that allow ecologists to transform massive datasets into meaningful ecological insights, with particular emphasis on genomic research and large-scale spatial analysis.

Parallel Computing Paradigms for Ecological Big Data

High-Performance Computing Environments

Ecological research leverages diverse high-performance computing (HPC) environments to manage its computational workloads, each offering distinct advantages for particular types of analyses. Cluster computing provides tightly-coupled systems with high-speed interconnects (such as Infiniband) that are ideal for message-passing interface (MPI) applications where low latency is critical [3]. Grid computing offers virtually unlimited computational resources and data storage across distributed infrastructures, making it suitable for embarrassingly parallel problems or weakly-coupled simulations where communication requirements are less intensive [3]. Cloud computing delivers flexible, on-demand resources that can scale elastically with computational demands, particularly valuable for genomic research workflows with variable processing requirements [1].

Each environment supports different parallelization approaches. For genomic research, clusters and clouds have proven effective for sequence alignment and comparative genomics, while grid infrastructures have demonstrated promise for coupled problems in fluid and plasma mechanics relevant to environmental modeling [1] [3]. The choice of HPC environment depends fundamentally on the communication-to-computation ratio of the ecological analysis task, with tightly-coupled problems requiring low-latency architectures and loosely-coupled problems benefiting from the scale of distributed resources.

Parallel Programming Models and Frameworks

Ecologists employ several programming models to exploit many-core architectures effectively. The Message Passing Interface (MPI) enables distributed memory parallelism across multiple nodes, making it suitable for large-scale spatial analyses where domains can be decomposed geographically [3]. Open Multi-Processing (OpenMP) provides shared memory parallelism on single nodes with multiple cores, ideal for genome sequence processing tasks that can leverage loop-level parallelism [3]. Compute Unified Device Architecture (CUDA) and Open Computing Language (OpenCL) enable fine-grained parallelism on graphics processing units (GPUs), offering massive throughput for certain mathematical operations common in ecological modeling [3].

Hybrid approaches that combine these models often deliver optimal performance. For instance, MPI can handle coarse-grained parallelism across distributed nodes while OpenMP manages fine-grained parallelism within each node [3]. This strategy reduces communication overhead while maximizing computational density, particularly important for random forest models used in large-scale ecological mapping [2]. Scientific workflow systems such as Pegasus and Swift/T further facilitate parallel execution by automating task dependency management and resource allocation across distributed infrastructures [1].

Table 1: High-Performance Computing Environments for Ecological Data Analysis

| Computing Environment | Architecture Characteristics | Ideal Use Cases in Ecology | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster Computing | Tightly-coupled nodes with high-speed interconnects | Coupled CFD problems, spatial random forest models | Low-latency communication, proven performance for tightly-coupled problems |

| Grid Computing | Loosely-coupled distributed resources | Weakly-coupled problems, comparative genomics | Virtually unlimited resources, extensive data storage capabilities |

| Cloud Computing | Virtualized, on-demand resources | Genomic workflows, elastic processing needs | Flexible scaling, pay-per-use model, accessibility |

| GPU Computing | Massively parallel many-core processors | Sequence alignment, mathematical operations in ecological models | High computational density, energy efficiency for parallelizable tasks |

Domain-Specific Applications and Methodologies

Genomic Research: From Sequences to Ecological Insights

Genomic research represents one of the most data-intensive domains in ecology, particularly with the advent of next-generation sequencing technologies that can generate terabytes of data from a single experiment [1]. Comparative genomics, which aligns orthologous sequences across organisms to infer evolutionary relationships, requires sophisticated parallel implementations of algorithms such as BLAST, HMMER, ClustalW, and RAxML [1]. The computational challenge scales superlinearly with the number of genomes being compared, making many-core parallelism essential for contemporary studies involving hundreds or thousands of whole genomes.

Effective parallelization of genomic workflows follows two primary strategies. First, redesigning bioinformatics applications for parallel execution using MPI or other frameworks can yield significant performance improvements. Second, scientific workflow systems such as Tavaxy, Pegasus, and SciCumulus can automate the parallel execution of analysis pipelines across distributed computing infrastructures [1]. These approaches reduce processing time from weeks or months on standalone workstations to hours or days on HPC systems, enabling ecological genomics to keep pace with data generation.

Table 2: Parallel Solutions for Genomic Analysis in Ecological Research

| Software/Platform | Bioinformatics Applications | HPC Infrastructure | Performance Improvements |

|---|---|---|---|

| AMPHORA [1] | BLAST, ClustalW, HMMER, PhyML, MEGAN | Clusters and Grids | Scalable phylogenomics workflow execution |

| Hadoop-BAM [1] | Picard SAM JDK, SAMtools | Hadoop Clusters | Efficient processing of sequence alignment files |

| EDGAR [1] | BLAST | Clusters | Accelerated comparative genomics |

| Custom MPI Implementation [1] | HMMER | Clusters | Reduced processing time for sequence homology searches |

Large-Scale Ecological Mapping: The Spatial Validation Challenge

Large-scale ecological mapping faces distinct computational challenges, particularly in accounting for spatial autocorrelation (SAC) during model validation. A critical study mapping aboveground forest biomass in central Africa using 11.8 million trees from forest inventory plots demonstrated that standard non-spatial validation methods can dramatically overestimate model predictive power [2]. While random K-fold cross-validation suggested that a random forest model predicted more than half of the forest biomass variation (R² = 0.53), spatial validation methods accounting for SAC revealed quasi-null predictive power [2].

This discrepancy emerges because standard validation approaches ignore spatial dependence in the data, violating the core assumption of independence between training and test sets. Ecological data typically exhibit significant spatial autocorrelation—forest biomass in central Africa showed correlation ranges up to 120 km, while environmental and remote sensing predictors displayed even longer autocorrelation ranges (250-500 km) [2]. When randomly selected test pixels are geographically proximate to training pixels, they provide artificially optimistic assessments of model performance for predicting at truly unsampled locations.

Spatial Validation Methodologies

To address this critical issue, ecologists must implement spatial validation methodologies that explicitly account for SAC:

Spatial K-fold Cross-Validation: Observations are partitioned into K sets based on geographical clusters rather than random assignment [2]. This approach creates spatially homogeneous clusters that are used alternatively as training and test sets, ensuring greater spatial independence between datasets.

Buffered Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation (B-LOO CV): This method implements a leave-one-out approach with spatial buffers around test observations [2]. Training observations within a specified radius of each test observation are excluded, systematically controlling the spatial distance between training and test sets.

Spatial Block Cross-Validation: The study area is divided into regular spatial blocks, with each block serving sequentially as the validation set while models are trained on remaining blocks. This approach explicitly acknowledges that observations within the same spatial block are more similar than those in different blocks.

These spatial validation techniques require additional computational resources but provide more realistic assessments of model predictive performance for mapping applications. Implementation typically leverages many-core architectures to manage the increased computational load associated with spatial partitioning and repeated model fitting.

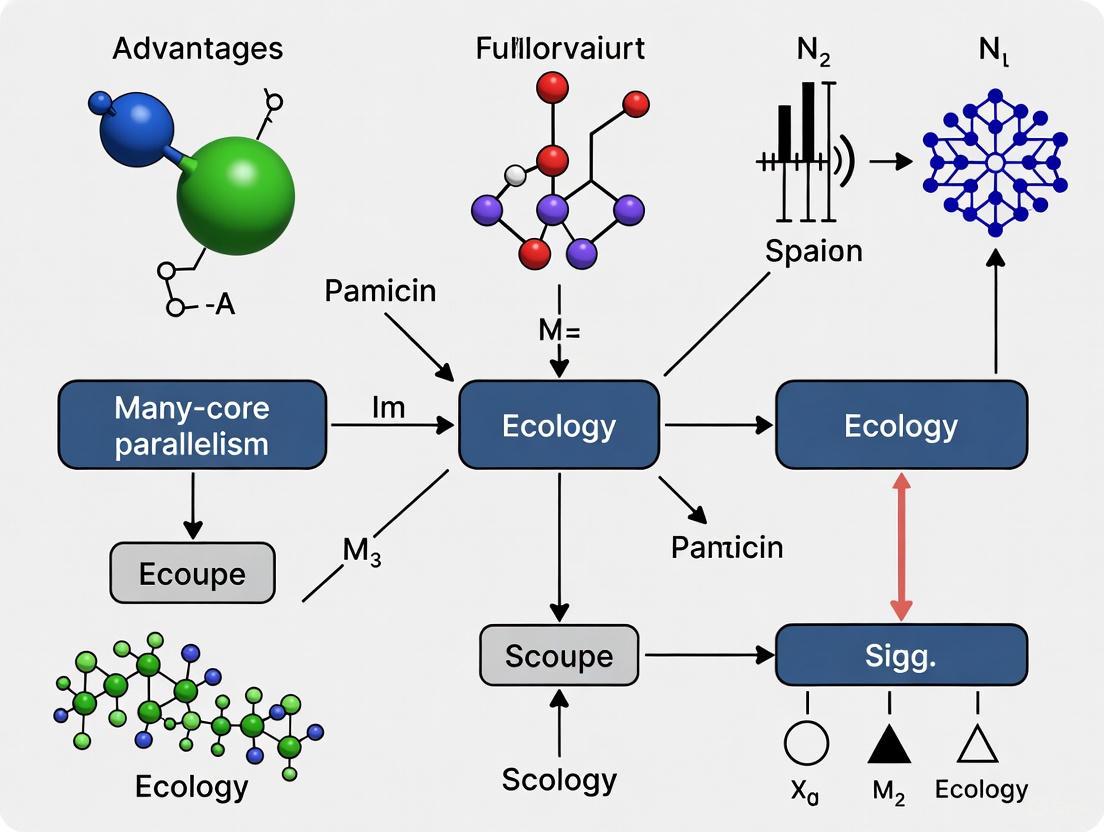

Visualization: Parallel Computing Workflow for Ecological Data

The following diagram illustrates the integrated parallel computing workflow for managing massive ecological datasets, from data ingestion through to analytical outcomes:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

Ecologists navigating the data deluge require both computational tools and methodological frameworks to ensure robust, scalable analyses. The following table details key solutions across different domains of ecological research:

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools and Methodologies for Ecological Big Data

| Tool/Category | Primary Function | Application Context | Parallelization Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest with Spatial CV [2] | Predictive modeling with spatial validation | Large-scale ecological mapping (e.g., forest biomass) | MPI-based parallelization across spatial blocks |

| BLAST Parallel Implementations [1] | Sequence similarity search and alignment | Comparative genomics, metagenomics | Distributed computing across clusters and grids |

| Scientific Workflow Systems (Pegasus, Swift/T) [1] | Automation of complex analytical pipelines | Genomic research, integrated ecological analyses | Task parallelism across distributed infrastructures |

| Spatial Cross-Validation Frameworks [2] | Robust model validation accounting for autocorrelation | Spatial ecological modeling, map validation | Spatial blocking with parallel processing |

| Hadoop-BAM [1] | Processing sequence alignment files | Genomic variant calling, population genetics | MapReduce paradigm on Hadoop clusters |

| CFD Parallel Solvers [3] | Simulation of fluid, gas and plasma mechanics | Environmental modeling, atmospheric studies | Hybrid MPI-OpenMP for coupled problems |

The challenges posed by massive ecological datasets are profound but not insurmountable. Through the strategic application of many-core parallelism across diverse computing infrastructures, ecologists can not only manage the data deluge but extract unprecedented insights from these rich information sources. The critical insights emerging from this exploration include the necessity of spatial validation techniques for large-scale ecological mapping to avoid overoptimistic performance assessments, and the importance of scalable genomic analysis frameworks that can keep pace with sequencing technological advances [2] [1].

Future directions will likely involve more sophisticated hybrid parallelization approaches that combine MPI, OpenMP, and GPU acceleration with emerging workflow management systems [3]. As ecological datasets continue to grow in size and complexity, the researchers who successfully integrate domain expertise with computational sophistication will lead the transformation of ecology into a more predictive science capable of addressing pressing environmental challenges.

The analysis of complex systems, particularly in ecology and drug discovery, has consistently pushed the boundaries of computational feasibility. From their initial stages, ecological models have been fundamentally nonlinear, but the recognition that these models must also be complex took longer to evolve. The "golden age" of mathematical ecology (1923-1940) employed highly aggregated differential equation models that described changes in population numbers using the law of conservation of organisms. The period from 1940-1975 saw a transition toward increased complexity with the introduction of age, stage, and spatial structures, though mathematical techniques like stability analysis remained dominant. The era of 1975-2000 marked a pivotal shift with the emergence of individual-based models (IBM) or agent-based models, which enabled more realistic descriptions of biological complexity in populations by tracking individuals rather than aggregated populations.

This evolution toward individual-based modeling represents a fundamental shift from aggregated differential equation models to frameworks that mechanistically represent ecological systems by tracking individuals rather than aggregated populations. The adoption of IBM approaches has transformed ecological modeling, creating opportunities for more realistic simulations while introducing significant computational burdens that strain traditional sequential processing capabilities. Similarly, in pharmaceutical research, the mounting volume of genomic knowledge and chemical compound space presents unprecedented opportunities for drug discovery, yet processing these massive datasets demands extraordinary computing resources that exceed the capabilities of conventional serial computation.

The end of the "MHz race" in processor development has fundamentally altered the computational landscape, forcing a transition from sequential to parallel computing architectures even at the desktop level. This paradigm shift necessitates new approaches to algorithm design and implementation across scientific domains, from ecological simulations to virtual screening in drug development. This technical guide examines the transformative potential of many-core parallelism in addressing these computational challenges, providing researchers with practical methodologies for leveraging parallel architectures to tackle previously infeasible scientific problems.

Theoretical Foundations of Parallel Computing in Scientific Simulation

Parallel Architecture Classifications and Capabilities

Modern parallel computing environments span a hierarchy from multi-core desktop workstations to many-core specialized devices and cloud computing clusters. The key architectural distinction lies between shared-memory systems, where multiple processors access common memory, and distributed-memory systems, where each processor has its own memory and communication occurs via message passing. Each architecture presents distinct advantages: shared-memory systems typically offer simpler programming models, while distributed-memory systems can scale to thousands of processors for massively parallel applications.

Table 1: Parallel Computing Architectures for Scientific Simulation

| Architecture Type | Core Range | Memory Model | Typical Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-core CPUs | 2-64 cores | Shared memory | Desktop simulations, moderate-scale ecological models |

| Many-core Devices (Intel Xeon Phi) | 60-72+ cores | Shared memory | High-throughput virtual screening, complex individual-based models |

| CPU Clusters | 16-1000+ cores | Distributed memory | Large-scale ecological community simulations, molecular dynamics |

| Cloud Computing Instances | 2-72+ cores (virtualized) | Virtualized hybrid | On-demand scaling for variable workloads, burst processing |

Benchmarking studies reveal compelling performance characteristics across these architectures. Testing of Amazon EC2 instances demonstrates near-linear speedup with additional cores, where a 72-core c5.18xlarge instance completed simulations in approximately 2 minutes compared to 50-80 minutes on a single core. This represents a 25-40x speedup, dramatically reducing computation time for large-scale simulations. Even older workstation-class hardware shows remarkable performance, with a refurbished HP Z620 workstation (16 cores) completing the same simulations in 5 minutes, demonstrating the cost-effectiveness of dedicated parallel hardware for research institutions.

Parallel Programming Frameworks and Paradigms

Multiple programming frameworks enable researchers to harness parallel architectures effectively. The dominant frameworks include OpenMP for shared-memory systems, which uses compiler directives to parallelize code; MPI (Message Passing Interface) for distributed-memory systems, which requires explicit communication between processes; and hybrid approaches that combine both paradigms. More recently, OpenCL has emerged as a framework for heterogeneous computing across CPUs, GPUs, and specialized accelerators, while HPX offers an asynchronous task-based model that can improve scalability on many-core systems.

The selection of an appropriate parallelization framework depends on both the algorithm structure and target architecture. For ecological individual-based models with independent individuals, embarrassingly parallel approaches where work units require minimal communication often achieve near-linear speedup. In contrast, models with frequent interactions between individuals require careful consideration of communication patterns and may benefit from hybrid approaches that optimize locality while enabling scalability.

Parallel Computing in Ecological Research: Methodologies and Applications

Tenets of Parallel Computational Ecology

Research in parallel ecological modeling has yielded three fundamental tenets that guide effective parallelization strategies. First, researchers must identify the correct unit of work for the simulation, which forms a silo of tasks to be completed before advancing to the next time step. Second, to distribute this work across multiple compute nodes, the work units generally require decoupling through the addition of supplementary information to each unit, reducing interdependencies that necessitate communication. Finally, once decoupled into independent work units, the simulation can leverage data parallelism by distributing these units across available processing cores.

Application of these principles to predator-prey models demonstrates their practical implementation. By coupling individual-based population models through a predation module, structured community models can distribute individual organisms across available processors while maintaining predator-prey interactions through specialized communication modules. This approach maintains the advantage of individual-based design, where feeding mechanisms and mortality expressions emerge from individual interactions rather than aggregate mathematical representations.

Individual-Based Model Parallelization: Daphnia and Fish Case Study

The parallelization of established aquatic individual-based models for Daphnia and rainbow trout illustrates a practical implementation pathway. These models, when combined into a structured predator-prey framework, exhibited execution times of several days per simulation under sequential processing. Through methodical parallelization, researchers achieved significant speedup while maintaining biological fidelity.

Table 2: Experimental Protocol for Ecological Model Parallelization

| Step | Methodology | Implementation Details |

|---|---|---|

| Problem Decomposition | Identify parallelizable components | Separate Daphnia, fish, and predation modules; identify data dependencies |

| Work Unit Definition | Determine atomic computation units | Individual organisms with their state variables and behavioral rules |

| Communication Pattern Design | Map necessary interactions | Implement predation as separate module; minimize inter-process communication |

| Load Balancing | Distribute work evenly across cores | Dynamic task allocation based on individual computational requirements |

| Implementation | Code using parallel frameworks | OpenMP for shared-memory systems; MPI for distributed systems |

| Validation | Verify parallel model equivalence | Compare output with sequential implementation; ensure statistical consistency |

The implementation revealed several practical computational challenges, including cache contention and CPU idling during memory access, which limited ideal speedup. Operating system scheduling also impacted performance, with improvements observed in newer OS versions that better maintained core affinity for long-running tasks. These real-world observations highlight the importance of considering hardware and software interactions in parallel algorithm design.

Figure 1: Parallelization Methodology Workflow for Ecological Models

Parallel Acceleration in Drug Discovery: A Comparative Analysis

Structure-Based Virtual Screening on Many-Core Architectures

The field of structure-based drug discovery has embraced many-core architectures to address the computational challenges of screening massive compound libraries. Modern virtual screening routinely evaluates hundreds of millions to over a billion compounds, a task that demands unprecedented computing resources. Heterogeneous systems equipped with parallel computing devices like Intel Xeon Phi many-core processors have demonstrated remarkable effectiveness in accelerating these workflows, delivering petaflops of peak performance to accelerate scientific discovery.

The implementation of algorithms such as eFindSite (ligand binding site prediction), biomolecular force field computations, and BUDE (structure-based virtual screening engine) on many-core devices illustrates the transformative potential of parallel computing in pharmaceutical research. These implementations leverage the massively parallel capabilities of modern accelerators, which feature tens of computing cores with hundreds of threads specifically designed for highly parallel workloads. The parallel programming frameworks employed include OpenMP, OpenCL, MPI, and HPX, each offering distinct advantages for different aspects of the virtual screening pipeline.

OptiPharm Parallelization: Protocol and Performance

The parallelization of OptiPharm, an algorithm designed for ligand-based virtual screening, demonstrates a systematic approach to leveraging parallel architectures. The implementation employs a two-layer parallelization strategy: first, automating molecule distribution between available nodes in a cluster, and second, parallelizing internal methods including initialization, reproduction, selection, and optimization. This comprehensive approach, implemented in the pOptiPharm software, addresses both inter-node and intra-node parallelism to maximize performance across diverse computing environments.

Table 3: Drug Discovery Parallelization Benchmark Results

| Application Domain | Algorithm | Parallelization Approach | Performance Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ligand-based Virtual Screening | OptiPharm | Two-layer parallelization: molecule distribution + method parallelization | Better solutions than sequential version with near-proportional time reduction |

| Structure-based Virtual Screening | BUDE | Many-core device implementation (Intel Xeon Phi) | Significant acceleration vs. traditional serial computing |

| Binding Site Prediction | eFindSite | Heterogeneous system implementation | Improved throughput for binding site identification |

| Coronavirus Protease Inhibition | Virtual Screening | High-throughput screening of 606 million compounds | Identified potential inhibitors through massive parallel processing |

Experimental results demonstrate that pOptiPharm not only reduces computation time almost proportionally to the number of processing units but also surprisingly finds better solutions than the sequential OptiPharm implementation. This counterintuitive result suggests that parallel exploration of compound space may more effectively navigate complex fitness landscapes, identifying superior candidates that sequential approaches might overlook within practical time constraints. This has significant implications for drug discovery workflows, where both speed and solution quality are critical factors in lead compound identification.

Performance Benchmarking and Scalability Analysis

Cross-Platform Performance Comparison

Rigorous benchmarking across computing platforms provides critical insights for researchers selecting appropriate hardware configurations. Comprehensive testing has compared performance across personal computers, workstations, and cloud computing instances using ecological simulations of longitudinally clustered data with three-level models fit with random intercepts and slopes.

Table 4: Hardware Performance Benchmarking Results

| Machine Configuration | CPU Details | Cores | Simulation Time | Relative Speedup |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MacBook Pro (2015) | Intel Core i7-4980HQ @ 2.8GHz | 4 | 13 minutes | 3.8x |

| HP Z620 Workstation | Xeon E5-2670 (dual CPU) @ 2.6GHz | 16 | 5 minutes | 12x |

| Amazon EC2 c5.4xlarge | Xeon Platinum 8124M @ 3.0GHz | 8 | 4 minutes | 12.5x |

| Amazon EC2 c5.18xlarge | Xeon Platinum 8124M @ 3.0GHz | 36 | 2 minutes | 25x |

| Sequential Baseline | Various | 1 | 50-80 minutes | 1x |

The results demonstrate several key patterns. First, speedup was generally linear with respect to physical core count across all tested configurations, indicating effective parallelization with minimal overhead. Second, the cloud computing instances showed competitive performance with on-premises hardware, providing viable alternatives for burst computing needs. Third, even older workstation-class hardware delivered substantial performance, with the HP Z620 completing simulations in 5 minutes despite its age, highlighting the cost-effectiveness of refurbished workstations for research groups with limited budgets.

Economic considerations play a crucial role in parallel computing adoption. Analysis reveals that a refurbished workstation capable of completing simulations in 5 minutes can be acquired for approximately 600 EUR, while comparable cloud computing capacity (c5.9xlarge instance) would incur similar costs after approximately 17 days of continuous usage. This economic reality strongly favors local hardware for sustained computational workloads while preserving cloud options for burst capacity or exceptionally large-scale simulations that exceed local capabilities.

The decision framework for researchers therefore depends on usage patterns: frequent large-scale simulations justify investment in local parallel workstations, while occasional extreme-scale computations benefit from cloud elasticity. Hybrid approaches that maintain modest local resources for development and testing while leveraging cloud resources for production runs offer a balanced strategy that optimizes both responsiveness and capability.

Figure 2: Decision Framework for Parallel Computing Resource Selection

The Scientist's Parallel Computing Toolkit

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Implementing effective parallel computing solutions requires both hardware infrastructure and software tools. The following toolkit represents essential components for researchers embarking on parallel simulation projects:

Table 5: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Parallel Computing

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Hardware Platforms | Multi-core workstations, Many-core devices, Cloud computing instances | Provide physical computation resources for parallel execution |

| Parallel Programming Frameworks | OpenMP, MPI, OpenCL, HPX | Enable code parallelization across different architectures |

| Performance Profiling Tools | Intel VTune, NVIDIA Nsight, ARM MAP | Identify performance bottlenecks and optimization opportunities |

| Benchmarking Suites | HPC Challenge, SPEC MPI, Custom domain-specific tests | Validate performance and compare hardware configurations |

| Development Environments | Parallel debuggers, Cluster management systems | Support development and deployment of parallel applications |

| Scientific Libraries | PETSc, Trilinos, Intel Math Kernel Library | Provide pre-optimized parallel implementations of common algorithms |

Implementation Best Practices and Optimization Strategies

Successful parallel implementation requires adherence to established best practices and performance optimization strategies. Workload distribution should prioritize data locality to minimize communication overhead, particularly for individual-based models with frequent interactions. Load balancing must dynamically address inherent imbalances in ecological simulations where individuals exhibit heterogeneous computational requirements. Communication minimization through batched updates and asynchronous processing can significantly enhance scalability, especially for distributed-memory systems.

Validation remains paramount throughout parallelization efforts, requiring rigorous comparison with sequential implementations to ensure equivalent results. Statistical validation of output distributions, conservation law verification, and comparative analysis of key emergent properties provide necessary quality control. Performance analysis should focus not only on execution time but also on parallel efficiency, strong scaling (fixed problem size), and weak scaling (problem size proportional to cores), providing comprehensive understanding of implementation characteristics.

The integration of these tools and practices enables researchers to effectively leverage parallel computing across scientific domains, transforming previously intractable problems into feasible investigations. This computational empowerment advances ecological understanding and accelerates therapeutic development, demonstrating the transformative potential of many-core parallelism in scientific research.

The field of ecological research is undergoing a computational revolution, driven by increasingly large and complex datasets from sources such as satellite imagery, genomic sequencing, and landscape-scale simulations. To extract meaningful insights from this deluge of information, ecologists are turning to many-core parallel processing, which provides the computational power necessary for advanced statistical analyses and model simulations. Parallel computing architectures, particularly Graphics Processing Units (GPUs), offer a pathway to performing computationally expensive ecological analyses at reduced cost, energy consumption, and time—attributes of increasing concern in environmental science. This shift is crucial for leveraging modern ecological datasets, making complex models viable, and extending these models to better reflect real-world environments [4].

The fundamental advantage of many-core architectures lies in their ability to execute thousands of computational threads simultaneously, a capability that aligns perfectly with the structure of many ecological problems. Agent-based models, spatial simulations, and statistical inference methods often involve repeating similar calculations across numerous independent agents, geographic locations, or data points. This data parallelism can be exploited by GPUs to achieve speedup factors of two orders of magnitude or more compared to traditional serial processing on Central Processing Units (CPUs) [4]. For instance, in forest landscape modeling, parallel processing can simulate multiple pixel blocks simultaneously, improving both computational efficiency and simulation realism by more closely mimicking concurrent natural processes [5].

Table 1: Key Parallel Computing Terms and Definitions

| Term | Definition | Relevance to Ecological Research |

|---|---|---|

| Data Parallelism | Distributing data across computational units that apply the same operation to different elements [6]. | Applying identical model rules to many landscape pixels or individual organisms simultaneously. |

| Task Parallelism | Executing different operations concurrently on the same or different data [6]. | Running dispersal, growth, and mortality calculations for different species at the same time. |

| Shared Memory | A programming model where multiple threads communicate through a common memory address space [6]. | Enables threads in a GPU block to collaboratively process a shared tile of spatial data. |

| Distributed Memory | A programming model where processes with separate memories communicate via message passing (e.g., MPI) [6]. | Allows different compute nodes to handle different geographic regions of a large-scale landscape model. |

| Thread Block | A group of CUDA threads that can synchronize and communicate via shared memory [6]. | A logical unit for parallelizing the computation of a local ecological process within a larger domain. |

Core Architectural Concepts: GPU Architecture and CUDA

GPU Execution Model

GPUs are architected for massive parallelism rather than the low-latency, sequential task execution favored by CPUs. A CPU is a flexible, general-purpose device designed to run operating systems and diverse applications efficiently, featuring substantial transistor resources dedicated to control logic and caching. In contrast, GPUs devote a much larger fraction of their transistors to mathematical operations, resulting in a structure containing thousands of simplified computational cores. These cores are designed to handle the highly parallel workloads inherent to 3D graphics and, by extension, scientific computation [6].

The GPU execution model is structured around the concept of over-subscription. For optimal performance, programmers launch tens of thousands of lightweight threads—far more than the number of physical cores available. These threads are managed with minimal context-switching overhead. This design allows the hardware to hide memory access latency effectively: when some threads are stalled waiting for data from memory, others can immediately execute on the computational cores. This approach contrasts with CPU optimization, which focuses on reducing latency for a single thread of execution through heavy caching and branch prediction [6].

CUDA Hierarchy: Threads, Warps, and Blocks

NVIDIA's CUDA (Compute Unified Device Architecture) platform provides a programming model that abstracts the GPU's parallel architecture. In CUDA, the fundamental unit of execution is the thread. Each thread executes the same kernel function but on different pieces of data, and has its own set of private registers and local memory [6].

Threads are organized into a hierarchical structure, which is crucial for understanding GPU programming:

- Warps: At the hardware level, threads are grouped into warps, which are collections of 32 threads that execute in lockstep on a Single Instruction, Multiple Threads (SIMT) unit. This means all threads in a warp execute the same instruction simultaneously on different data elements. A significant performance consideration is warp divergence, which occurs when threads within a warp take different execution paths based on a conditional statement. In this case, both paths are executed sequentially, with some threads inactive during each path, potentially reducing performance [6].

- Thread Blocks: A block is a user-defined group of threads, typically containing multiple warps. Threads within the same block can cooperate efficiently: they can be synchronized and can communicate through a high-speed, on-chip memory called shared memory. Each thread block is scheduled to execute on a single Streaming Multiprocessor (SM) within the GPU [6].

- Grid: The highest level of the hierarchy is the grid, which comprises all the thread blocks launched for a given kernel. Blocks within a grid are independent and cannot synchronize or communicate directly via shared memory; they must use global memory for any data exchange [6].

Memory Hierarchy and Coalesced Access

The GPU memory system is a critical factor in achieving high performance. It is structured as a hierarchy, with different types of memory offering a trade-off between capacity, speed, and scope of access.

- Global Memory: This is the large, high-latency memory accessible to all threads in a grid. It is the primary means for transferring data between the host (CPU) and device (GPU) and for sharing data between different thread blocks. Access to global memory is most efficient when it is coalesced; that is, when the threads in a warp access contiguous, aligned blocks of memory. This pattern allows the memory system to bundle multiple accesses into a single, efficient transaction [6].

- Shared Memory: Each SM contains a small, ultra-fast, on-chip memory that can be used as programmer-managed shared memory. It is allocated per thread block and is shared by all threads within that block. Shared memory acts as a user-controlled cache, enabling threads to collaboratively stage data, avoid redundant global memory accesses, and communicate results efficiently. Its latency can be roughly 100x lower than that of uncached global memory, provided accesses do not cause bank conflicts [7].

- Registers and Local Memory: The fastest memory available is the set of registers allocated to each thread. Variables declared locally in a kernel are typically stored in registers. If a variable does not fit in registers, it is spilled to slow local memory, which is actually a reserved portion of global memory, hurting performance.

The key to high-performance GPU code is to exploit this hierarchy effectively: keeping data as close to the computational cores as possible (in registers and shared memory) and minimizing and coalescing accesses to global memory.

Shared vs. Distributed Memory Models

Shared Memory Systems

In a shared memory architecture, multiple computational units (cores) have access to a common, unified memory address space. This is the model used within a single GPU and within a single multi-core CPU. The primary advantage of this model is the simplicity of communication and data sharing between threads: since all memory is globally accessible, threads can communicate by simply reading from and writing to shared variables. However, this requires careful synchronization mechanisms, such as barriers and locks, to prevent race conditions where the outcome depends on the non-deterministic timing of thread execution [6].

On a GPU, the shared memory paradigm extends to its on-chip scratchpad. Threads within a block can write data to shared memory, synchronize using the __syncthreads() barrier, and then reliably read the data written by other threads in the same block. This capability is the foundation for many cooperative parallel algorithms, such as parallel reductions and efficient matrix transposition [7].

Distributed Memory Systems

A distributed memory architecture consists of multiple nodes, each with its own independent memory. Computational units on one node cannot directly access the memory of another node. This is the model used in computer clusters and supercomputers. Communication between processes running on different nodes must occur via an explicit message passing protocol, such as the Message Passing Interface (MPI) [6].

The primary advantage of distributed memory systems is their scalability; by adding more nodes, the total available memory and computational power can be increased almost indefinitely. The main challenge is that the programmer is responsible for explicitly decomposing the problem and data across nodes and managing all communication, which can be complex and introduce significant overhead if not done carefully [6].

Hybrid Models

Many high-performance computing applications, including large-scale ecological simulations, employ a hybrid model that combines both shared and distributed memory paradigms. For example, the parallel ant colony algorithm for Sunway many-core processors (SWACO) uses a two-level parallel strategy. It employs process-level parallelism using MPI (a distributed memory model) to divide the initial ant colony into multiple sub-colonies that compute on different "islands." Within each island, it then uses thread-level parallelism (a shared memory model) to leverage the computing power of many slave cores for path selection and pheromone updates [8]. This hybrid approach effectively leverages the strengths of both models to solve complex optimization problems.

Table 2: Comparison of Shared and Distributed Memory Architectures

| Characteristic | Shared Memory | Distributed Memory |

|---|---|---|

| Memory Address Space | Single, unified address space for all processors [6]. | Multiple, private address spaces; no direct memory access between nodes [6]. |

| Communication Mechanism | Through reads/writes to shared variables; requires synchronization [6]. | Explicit message passing (e.g., MPI) [6]. |

| Programming Model | Thread-based (e.g., Pthreads, OpenMP, CUDA threads) [6]. | Process-based (e.g., MPI) [6]. |

| Hardware Scalability | Limited by memory bandwidth and capacity of a single system [6]. | Highly scalable by adding more nodes [6]. |

| Primary Challenge | Managing race conditions and data consistency via synchronization [7]. | Decomposing the problem and managing communication overhead [6]. |

| Example in Ecology | A GPU accelerating a local bird movement simulation [9]. | An MPI-based landscape model distributed across a supercomputer [8]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Technologies and Reagents

Ecologists and environmental scientists venturing into parallel computing will encounter a suite of essential software tools and hardware platforms. The following table details key "research reagents" in the computational parallel computing domain.

Table 3: Essential "Reagent" Solutions for Parallel Computational Ecology

| Tool/Technology | Type | Primary Function | Example in Ecological Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| CUDA | Programming Platform | An API and model for parallel computing on NVIDIA GPUs, enabling developers to write kernels that execute on the GPU [7]. | Accelerating parameter inference for a Bayesian grey seal population model [4]. |

| MPI (Message Passing Interface) | Library Standard | A standardized library for message-passing communication between processes in a distributed memory system [6]. | Enabling process-level parallelism in the SWACO algorithm on Sunway processors [8]. |

| Athread | Library | A dedicated accelerated thread library for Sunway many-core processors [8]. | Managing thread-level parallelism on the CPEs of a Sunway processor for an ant colony algorithm [8]. |

| GPU (NVIDIA A100) | Hardware | A many-core processor with thousands of CUDA cores and high-bandwidth memory, optimized for parallel data processing. | Served as the test hardware for shared memory microbenchmarks, demonstrating 1.4 gigaloads/bank/second [10]. |

| Sunway 26010 Processor | Hardware | A heterogeneous many-core processor featuring Management Processing Elements (MPEs) and 64 Computation Processing Elements (CPEs) per core group [8]. | Used as the platform for the parallel SWACO algorithm, achieving a 3-6x speedup [8]. |

Experimental Protocols and Performance Benchmarks

Case Study 1: GPU-Accelerated Statistical Ecology

Objective: To demonstrate the significant speedup achievable by implementing computationally intensive ecological statistics algorithms on GPU architecture.

Methodology: This study focused on two core algorithms in statistical ecology [4]:

- Bayesian State-Space Model Inference: A particle Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) method was implemented for a grey seal population dynamics model.

- Spatial Capture-Recapture: A framework for animal abundance estimation was accelerated using GPU parallelism.

The experimental protocol involved:

- Baseline Establishment: The algorithms were first run on traditional multi-core CPU systems to establish baseline performance.

- GPU Implementation: The algorithms were re-implemented for GPU execution using the CUDA platform. This involved designing kernels to parallelize the most computationally demanding components, such as likelihood calculations across many particles (for MCMC) or integration points (for capture-recapture).

- Performance Validation: The results from the GPU implementation were rigorously compared to the CPU baseline to ensure statistical equivalence and correctness.

- Performance Benchmarking: The computational throughput and execution time for both implementations were measured and compared.

Results: The GPU-accelerated implementation yielded speedup factors of over two orders of magnitude for the particle MCMC, providing a highly efficient alternative to state-of-the-art CPU fitting algorithms. For the spatial capture-recapture analysis with a high number of detectors and mesh points, a similar speedup was possible. When applied to real-world photo-identification data of common bottlenose dolphins, a speedup factor of 20 was achieved compared to using multiple CPU cores and open-source software [4].

Case Study 2: Parallel Ant Colony Optimization on Sunway Many-Core Processors

Objective: To design and evaluate a parallel Ant Colony Optimization (ACO) algorithm tailored for the unique heterogeneous architecture of the Sunway many-core processor, aiming to significantly reduce computation time for complex route planning problems like the Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP).

Methodology: The study proposed the SWACO algorithm, which employs a two-level parallel strategy [8]:

- Process-Level Parallelism (Island Model): The initial ant colony is divided into multiple child ant colonies based on the number of available processor groups. Each child colony independently performs computations on its own "island," a form of coarse-grained parallelism implemented using MPI.

- Thread-Level Parallelism: Within each island, the computational power of the 64 CPEs (Computing Processing Elements) in a Sunway core group is harnessed. This is achieved using the Athread library to accelerate the path selection and pheromone update stages of the ACO algorithm, which constitute the most intensive parts of the computation.

Experimental Workflow:

- Setup: The algorithm was tested on multiple standard TSP datasets.

- Execution: The performance of the parallel SWACO was compared against a serial implementation of the ACO.

- Metrics: The key metrics were computation time, speedup ratio (serial time / parallel time), and solution quality (gap from the known optimal solution).

Results: The experiments demonstrated that the SWACO algorithm significantly reduced computation time across multiple TSP datasets. An overall speedup ratio of 3 to 6 times was achieved, with a maximum speedup of 5.72 times, while maintaining solution quality by keeping the optimality gap within 5% [8]. This showcases a substantial acceleration effect achieved by aligning the parallel algorithm with the specific target hardware architecture.

Case Study 3: Shared Memory Microbenchmarks on an NVIDIA A100

Objective: To quantitatively analyze the performance characteristics of GPU shared memory, with a specific focus on the impact of bank conflicts and the efficacy of different access patterns.

Methodology: A series of precise microbenchmarks were written and executed on an NVIDIA A100 GPU [10]. These kernels used inline PTX assembly to make controlled, volatile shared memory loads.

- Conflict-Free Access: Each thread in a warp loaded from a distinct, aligned bank.

- Full Bank Conflict: All 32 threads in a warp loaded from different addresses within the same bank.

- Multicast Patterns: All threads, or subsets of threads, loaded from the same single address.

- Vectorized Loads: Using

ld.shared.v4.f32instructions to perform 4-wide contiguous loads.

Results Summary:

- Peak Bandwidth: The conflict-free access benchmark achieved a rate of 1.4 gigaloads/bank/second, matching the A100's peak frequency of 1.4 GHz and confirming the theoretical maximum of one 32-bit load per bank per cycle [10].

- Bank Conflict Penalty: The full bank conflict scenario took 18.2 ms, which was 32 times longer than the conflict-free benchmark (0.57 ms). This result confirms that accesses to the same bank are serialized, drastically reducing performance [10].

- Multicast Efficiency: Benchmarks where all threads, or arbitrary groups of threads, loaded the same value from a single bank completed in 0.57 ms, the same time as conflict-free loads. This demonstrates the hardware's ability to efficiently broadcast/multicast data to multiple threads at no extra cost [10].

- Vector Load Performance: The 4-wide vectorized loads took 2.27 ms (4x longer than scalar loads) but transferred 4x more data, thus maintaining the same throughput of 4 bytes per lane per cycle, thanks to sophisticated hardware scheduling that avoids bank conflicts [10].

Table 4: Summary of Shared Memory Microbenchmark Results on A100

| Access Pattern | Execution Time (ms) | Relative Time | Key Performance Insight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conflict-Free | 0.57 [10] | 1x | Achieves peak theoretical bandwidth (1 load/bank/cycle). |

| Full Bank Conflict | 18.2 [10] | ~32x | Accesses to a single bank from a full warp are serialized. |

| Multicast/Broadcast | 0.57 [10] | 1x | Broadcasting a single value to many threads is highly efficient. |

| 4-Wide Vector Load | 2.27 [10] | ~4x | Maintains peak throughput for contiguous 128-bit loads. |

The field of ecology is undergoing a computational revolution driven by increasingly large and complex datasets from sources like remote sensors, DNA sequencing, and long-term monitoring networks [11]. This deluge of data presents both unprecedented opportunities and significant computational challenges for ecological research. Many-core parallelism has emerged as a critical technological solution, enabling researchers to leverage modern computing architectures to process ecological data at unprecedented scales and speeds [4]. This paradigm shift from serial to parallel computation represents a fundamental transformation in how ecological analysis is conducted.

Ecological workflows typically consist of multiple computational steps that transform raw data into ecological insights, often involving data preprocessing, statistical analysis, model fitting, and visualization [12]. The mapping of these workflows to parallel architectures requires identifying inherently parallelizable tasks and understanding how to decompose ecological problems to exploit various forms of parallelism. When successfully implemented, parallel computing can accelerate ecological analyses by multiple orders of magnitude, making previously infeasible investigations routine and enabling more complex, realistic models of ecological systems [4].

This technical guide examines how ecological workflows can be effectively mapped to parallel computing architectures, focusing specifically on identifying tasks that naturally lend themselves to parallelization. By understanding both the computational patterns in ecological research and the capabilities of parallel architectures, researchers can significantly enhance their analytical capabilities and address increasingly complex ecological questions.

Foundations of Parallel Computing in Ecology

Parallel Architecture Types and Ecological Applications

Ecological research utilizes diverse parallel computing architectures, each offering distinct advantages for different types of ecological workflows. Understanding these architectural options is essential for effective mapping of ecological tasks to appropriate computing resources.

Table 1: Parallel Computing Architectures in Ecological Research

| Architecture Type | Key Characteristics | Typical Ecological Applications | Performance Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-core CPU | Multiple processing cores on single chip; shared memory access | Individual-based models, statistical analysis, data preprocessing | Limited by memory bandwidth; optimal for coarse-grained parallelism |

| GPU (Graphics Processing Unit) | Massively parallel architecture with thousands of cores; SIMT architecture | Metagenomic sequence analysis, spatial simulations, parameter sweeps | Excellent for data-parallel tasks; requires specialized programming |

| Cluster Computing | Multiple computers connected via high-speed network; distributed memory | Ecosystem models, large-scale simulations, workflow orchestration | Communication overhead between nodes can impact performance |

| Cloud Computing | Virtualized resources on-demand; scalable and flexible | Web-based ecological platforms, scalable data processing | Pay-per-use model; excellent for variable workloads |

| Hybrid Architectures | Combination of CPU, GPU, and other accelerators | Complex multi-scale ecological models | Maximizes performance but increases programming complexity |

GPU acceleration has demonstrated particularly impressive results in ecological applications. In one case study focusing on parameter inference for a Bayesian grey seal population dynamics state space model, researchers achieved speedup factors of over two orders of magnitude using GPU-accelerated particle Markov chain Monte Carlo methods compared to traditional approaches [4]. Similarly, in spatial capture-recapture analysis for animal abundance estimation, GPU implementation achieved speedup factors of 20-100× compared to multi-core CPU implementations, depending on the number of detectors and integration mesh points [4].

Forms of Parallelism in Ecological Workflows

Ecological workflows exhibit different forms of parallelism that can be exploited by appropriate computing architectures:

- Data-level parallelism: The same operation applied to independent ecological datasets (e.g., processing samples from different field sites) [13]

- Task-level parallelism: Independent computational tasks that can execute concurrently (e.g., simultaneous model runs with different parameters) [12]

- Model-level parallelism: Decomposition of a single ecological model into components that can execute simultaneously (e.g., individual-based models where each organism's dynamics are computed in parallel) [14]

- Pipeline parallelism: Different stages of ecological workflow executing concurrently on different data elements (e.g., simultaneous data processing, analysis, and visualization) [15]

The key insight for ecological researchers is that most ecological workflows contain elements of multiple parallelism types, and effective mapping to parallel architectures requires identifying which forms dominate a given workflow.

Characterizing Ecological Workflows for Parallelization

Structural Patterns in Ecological Workflows

Ecological workflows generally follow recognizable structural patterns that have significant implications for parallelization strategies. These patterns determine how effectively a workflow can be distributed across multiple computing cores and what architectural approach will yield the best performance.

Table 2: Ecological Workflow Patterns and Parallelization Characteristics

| Workflow Pattern | Description | Inherent Parallelism | Example Ecological Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Serial Chain | Sequential execution where output of one step becomes input to next | Low | Traditional population models with sequential life stages |

| Parallel Branches | Independent tasks that can execute simultaneously | High | Multi-species community analysis; independent site processing |

| Iterative Loops | Repeated execution of similar operations on different data | Medium to High | Parameter optimization; model calibration; bootstrap analyses |

| Nested Hierarchy | Multiple levels of parallelization within workflow | High | Ecosystem models with parallel species dynamics and environmental interactions |

| Conditional Execution | Execution path depends on data or intermediate results | Low to Medium | Adaptive sampling strategies; hypothesis-driven analysis pipelines |

The parallel branches pattern is particularly amenable to parallelization. Research has shown that workflow systems supporting parallel branching, such as Dify Workflow, can significantly accelerate ecological analyses by enabling simultaneous processing of different tasks within the same analytical framework [15]. These systems support various parallelization approaches including simple parallelism (independent subtasks), nested parallelism (multi-level parallel structures), iterative parallelism (parallel processing within loops), and conditional parallelism (different parallel tasks based on conditions) [15].

Computational Characteristics of Ecological Tasks

The potential for parallelization of ecological workflows depends heavily on their computational characteristics, which determine what architectural approach will be most effective and what performance gains can be expected.

This decision framework illustrates the architectural selection process based on workflow characteristics. Data-intensive tasks with simple, uniform operations on large datasets (e.g., metagenomic sequence alignment) are ideal candidates for GPU acceleration [13]. Compute-intensive tasks with more complex logic but still significant parallelism (e.g., individual-based population simulations) work well on multi-core CPU architectures [14]. Embarrassingly parallel tasks with minimal communication requirements (e.g., parameter sweeps, multiple model runs) can efficiently utilize computing clusters [1], while complex workflows with multiple computational patterns may require hybrid approaches [12].

Identifying Inherently Parallelizable Ecological Tasks

Highly Parallelizable Ecological Computational Patterns

Certain computational patterns in ecology demonstrate particularly high potential for parallelization and can achieve near-linear speedup on appropriate architectures. These patterns represent the "low-hanging fruit" for researchers beginning to explore parallel computing.

Monte Carlo Simulations and Bootstrap Methods are extensively used in ecological statistics for uncertainty quantification and parameter estimation. These methods involve running the same computational procedure hundreds or thousands of times with different random seeds or resampled data. A study implementing GPU-accelerated Bayesian inference for population dynamics models demonstrated speedup factors exceeding 100×, reducing computation time from days to hours or even minutes [4]. The parallelization approach involves distributing independent simulations across multiple cores, with minimal communication overhead between computations.

Individual-Based Models (IBMs) represent another highly parallelizable ecological application. In IBMs, each organism can be treated as an independent computational entity, with their interactions and life history processes computed in parallel. Research on parallel Daphnia models demonstrated that careful workload distribution across multiple cores could significantly accelerate population simulations while maintaining biological accuracy [16] [14]. The key to effective parallelization of IBMs lies in efficient spatial partitioning and management of individual interactions across processor boundaries.

Metagenomic Sequence Analysis represents a data-intensive ecological application particularly suited to GPU acceleration. The Parallel-META pipeline demonstrates how metagenomic binning—the process of assigning sequences to taxonomic groups—can be accelerated by 15× or more through parallelization of similarity-based database searches using both GPU and multi-core CPU optimization [13]. This performance improvement makes computationally intensive analyses like comparative metagenomics across multiple samples practically feasible for ecological researchers.

Moderate to Low Parallelizability Tasks

Not all ecological computations benefit equally from parallelization. Some tasks exhibit inherent sequential dependencies or communication patterns that limit potential speedup.

Complex Dynamic Ecosystem Models with tight coupling between components often face parallelization challenges. When ecological processes operate at different temporal scales or have frequent interactions, the communication overhead between parallel processes can diminish performance gains. Research on parallel predator-prey models revealed that careful design of information exchange between computational units is essential for maintaining model accuracy while achieving speedup [14].

Sequential Statistical Workflows where each step depends directly on the output of previous steps demonstrate limited parallelization potential. For example, traditional time-series analysis of population data often requires sequential processing of observations through filtering, smoothing, and parameter estimation steps. While individual components might be parallelized, the overall workflow remains constrained by its sequential dependencies.

Implementation Framework for Parallel Ecological Workflows

The Scientist's Parallel Computing Toolkit

Successfully implementing parallel ecological workflows requires familiarity with both computational tools and ecological domain knowledge. The following toolkit provides essential components for researchers developing parallel ecological applications.

Table 3: Essential Tools for Parallel Ecological Computing

| Tool Category | Specific Technologies | Ecological Application Examples | Key Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parallel Programming Models | MPI, OpenMP, CUDA, Apache OpenWhisk | Distributed ecosystem models, GPU-accelerated statistics | Abstraction of parallel hardware; performance portability |

| Workflow Management Systems | Dify Workflow, Pegasus, Tavaxy, SciCumulus | Automated analysis pipelines; multi-model forecasting | Orchestration of complex parallel tasks; reproducibility |

| Data Management & Storage | MongoDB, Hadoop-BAM, specialized file formats | Large ecological datasets; genomic data; sensor networks | Efficient I/O for parallel applications; data partitioning |

| Performance Analysis Tools | Profilers, load balancing monitors, debugging tools | Optimization of individual-based models; parameter tuning | Identification of parallelization bottlenecks; performance optimization |

| Visualization Frameworks | Plotly, D3.js, Parallel Coordinates | Multivariate ecological data exploration; model output comparison | Interpretation of high-dimensional ecological data |

The EcoForecast system exemplifies how these tools can be integrated into a comprehensive platform for ecological analysis. This serverless platform uses Apache OpenWhisk to execute ecological computations in containerized environments, automatically managing resource allocation across different computing infrastructures from powerful core cloud resources to geographically distributed edge computing nodes [12]. This approach allows ecological researchers to leverage parallel computing capabilities without requiring deep expertise in parallel programming.

Experimental Protocol for Parallelization of Ecological Workflows

Implementing parallel ecological workflows follows a systematic methodology that ensures both computational efficiency and ecological validity. The following protocol provides a structured approach for researchers:

Phase 1: Workflow Analysis and Profiling

- Document all computational steps in the existing ecological workflow

- Identify data dependencies between workflow components

- Measure current execution time of each component using profiling tools

- Classify each component as data-intensive, compute-intensive, or communication-intensive

- Estimate potential parallelism using the parallelization decision framework (Section 3.2)

Phase 2: Parallelization Strategy Selection

- Map workflow components to appropriate parallel patterns (Section 3.1)

- Select target architecture based on workflow characteristics (Table 1)

- Choose appropriate programming model and tools (Table 3)

- Design data decomposition strategy to minimize communication overhead

- Plan for load balancing across available computational resources

Phase 3: Implementation and Optimization

- Develop parallel version using selected tools and frameworks

- Implement efficient data structures for parallel access

- Incorporate appropriate synchronization mechanisms

- Optimize memory usage and data movement patterns

- Implement checkpointing for long-running ecological simulations

Phase 4: Validation and Performance Evaluation

- Verify ecological accuracy by comparing results with serial implementation

- Measure speedup relative to original implementation

- Analyze scaling behavior with increasing core counts

- Identify and address any performance bottlenecks

- Document any ecological trade-offs or approximations introduced by parallelization

Research on parallel ecological modeling has established that following a structured parallelization methodology typically yields 2-10× speedup for moderately parallelizable workflows and 10-100× or more for highly parallelizable applications on appropriate hardware [4] [13] [14].

Case Studies in Parallel Ecological Workflow Implementation

Case Study 1: Parallel Metagenomic Analysis Pipeline

The Parallel-META pipeline for metagenomic analysis demonstrates effective mapping of data-intensive ecological workflows to hybrid parallel architectures. This case study illustrates the implementation of a production-grade parallel ecological workflow.

The Parallel-META implementation demonstrates several key principles for parallel ecological workflows. First, it employs hybrid parallelization using both GPU acceleration for highly parallel sequence alignment and multi-core CPU processing for other computational steps [13]. Second, it implements pipeline parallelism by overlapping different processing stages. Third, it includes data-level parallelism by processing multiple samples simultaneously. This architecture achieved 15× speedup over serial metagenomic analysis methods while maintaining equivalent analytical accuracy [13].

Case Study 2: Parallel Individual-Based Ecosystem Model

Research on parallel simulation of structured ecological communities provides insights into mapping complex ecological models to parallel architectures. This case study focuses on a predator-prey model incorporating individual-based representations of both Daphnia and fish populations.

The parallel implementation followed three key tenets established for parallel computational ecology [14]:

Identification of appropriate work units: The simulation was decomposed into individual organisms as the fundamental unit of work, with each processor handling a subset of individuals.

Decoupling through information addition: To enable parallel execution, each work unit was supplemented with necessary environmental information, particularly spatial coordinates that determined interaction potentials.

Efficient work distribution: A dynamic load-balancing approach distributed individuals across available cores based on computational requirements, which varied throughout the simulation.

The parallel implementation faced significant challenges in managing spatial interactions between individuals, particularly predator-prey relationships that required communication between processors. The solution involved duplicating critical environmental information across processors and implementing efficient nearest-neighbor communication patterns [14]. Despite these challenges, the parallel individual-based model demonstrated substantial speed improvements over the serial implementation while maintaining ecological realism, enabling more extensive parameter exploration and longer-term simulations than previously possible.

Mapping ecological workflows to parallel architectures requires systematic identification of inherently parallelizable tasks and careful matching of computational patterns to appropriate hardware. The most significant speedups are achievable for ecological tasks exhibiting data-level parallelism (e.g., metagenomic sequence analysis), embarrassing parallelism (e.g., Monte Carlo simulations), and individual-based modeling with localized interactions.

Successful parallelization extends beyond mere computational acceleration—it enables entirely new approaches to ecological research. By reducing computational constraints, parallel computing allows ecologists to incorporate greater biological complexity, analyze larger datasets, and explore broader parameter spaces in their models. As ecological data continue to grow in volume and complexity, leveraging many-core parallelism will become increasingly essential for extracting meaningful ecological insights from available data.

The future of parallel computing in ecology will likely involve more sophisticated hybrid architectures, increasingly accessible cloud-based parallel resources, and greater integration of parallel computing principles into ecological methodology. By adopting the frameworks and approaches outlined in this guide, ecological researchers can effectively harness many-core parallelism to advance understanding of complex ecological systems.

The integration of many-core parallelism into ecological research represents a paradigm shift, enabling scientists to move from descriptive analytics to predictive, high-resolution modeling. This technical guide demonstrates how parallel computing architectures are fundamentally accelerating the pace of ecological insight, allowing researchers to address critical conservation challenges with unprecedented speed and scale. By leveraging modern computational resources, ecologists can now process massive spatial datasets, run complex simulations across extended time horizons, and optimize conservation strategies in near real-time—transforming our capacity for effective environmental stewardship in an era of rapid global change.

Ecology has evolved from an observational science to a data-intensive, predictive discipline. Contemporary conservation biology grapples with massive datasets from remote sensing, camera traps, acoustic monitoring, and genomic sequencing, while simultaneously requiring complex process-based models to forecast ecosystem responses to anthropogenic pressures. Traditional sequential processing approaches have become inadequate for these computational demands, creating a critical bottleneck in translating data into actionable conservation insights.

Many-core parallelism—the coordinated use of numerous processing units within modern computing architectures—provides the necessary foundation to overcome these limitations. From multi-core CPUs and many-core GPUs to distributed computing clusters, parallel processing enables researchers to decompose complex ecological problems into manageable components that can be processed simultaneously. This technical guide examines the practical implementation of parallel computing in conservation science, detailing specific methodologies, performance gains, and implementation frameworks that deliver the "real-world payoff" of dramatically accelerated scientific insight for more timely management decisions.

Technical Foundations of Parallel Computing in Ecology

Essential Parallel Computing Concepts

Parallel computing involves the simultaneous use of multiple computing resources to solve computational problems by breaking them into discrete parts that can execute concurrently across different processors [17]. Several theoretical frameworks and laws govern the practical implementation and performance expectations for parallel systems:

- The PRAM Model: The Parallel Random Access Machine (PRAM) provides an idealized abstraction where multiple processors operate synchronously and share a common memory. While primarily theoretical, it informs algorithm design for ecological modeling [17].

- Bulk Synchronous Parallel (BSP) Model: This model segments computation into "supersteps" consisting of local computation, communication, and barrier synchronization phases, explicitly capturing communication costs relevant to distributed ecological simulations [17].

- Amdahl's Law: This principle quantifies the maximum potential speedup of a parallel program, highlighting that even small serial fractions fundamentally limit scalability:

S(P) = 1/(f + (1-f)/P)wherefis the serial fraction andPis the number of processors [17]. - Gustafson's Law: Offering a more optimistic perspective, this law argues that as problem sizes increase (common in ecological modeling), the parallelizable portion often grows, mitigating the impact of serial sections [17].

Parallelization Modalities for Ecological Workloads

Ecological computations can be parallelized through several distinct approaches, each with specific implementation characteristics and suitability for different problem types:

Table: Parallelization Modalities for Ecological Research

| Modality | Description | Ecological Applications | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-threaded Execution | Multiple threads within a single process share memory space | In-memory spatial operations, statistical computations | OpenMP, Java Threads, Python threading |

| Multi-process Execution | Separate processes with independent memory spaces | Independent model runs, parameter sweeps, ensemble forecasting | MPI, Python multiprocessing, GNU Parallel |

| Cluster Parallel Execution | Distributed processes across multiple physical nodes | Large-scale landscape models, continental-scale biodiversity assessments | MPI, Apache Spark, Parsl |

| Pleasingly Parallel | Embarrassingly parallel problems with minimal interdependency | Species distribution model calibration, image processing for camera trap data | GNU Parallel, job arrays on HPC systems |

The choice of parallelization approach depends on multiple factors including data dependencies, communication patterns, hardware architecture, and implementation complexity. For many ecological applications, "pleasingly parallel" problems—where tasks can execute independently with minimal communication—offer the most straightforward path to significant performance gains [18].

Case Study: Parallelizing Forest Landscape Models

Experimental Protocol and Methodology

Forest Landscape Models (FLMs) represent computationally intensive ecological simulations that model complex spatial interactions across forest ecosystems. A recent implementation demonstrated the transformative impact of parallelization on these models through the following experimental approach [5]:

- Spatial Domain Decomposition: The landscape was partitioned into pixel subsets (blocks) assigned to individual processing cores, enabling simultaneous computation of species- and stand-level processes across the landscape.

- Dynamic Load Balancing: Pixel subsets were dynamically reallocated across cores during execution to efficiently handle landscape-level processes with different computational characteristics, particularly seed dispersal.

- Comparative Framework: Simulation results from parallel processing were rigorously compared against traditional sequential processing to evaluate both computational performance and ecological realism.