Long-Term Ecological Research (LTER): A Foundational Guide for Researchers and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of Long-Term Ecological Research (LTER), a critical framework for understanding ecosystem dynamics over decades.

Long-Term Ecological Research (LTER): A Foundational Guide for Researchers and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of Long-Term Ecological Research (LTER), a critical framework for understanding ecosystem dynamics over decades. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we demystify LTER's core principles, its sophisticated methodologies for data collection and management, and its powerful applications in identifying environmental trends. The content further addresses the challenges of long-term studies and offers optimization strategies, concluding with a forward-looking perspective on how LTER frameworks and ecological insights are informing biomedical innovation and predictive health modeling.

What is Long-Term Ecological Research? Defining the Cornerstone of Environmental Science

The Long-Term Ecological Research (LTER) program, established by the National Science Foundation (NSF) in 1980, represents a foundational shift in ecological science, moving beyond short-term observational studies to a sophisticated, networked investigation of ecological phenomena over decadal and larger spatial scales [1] [2]. This whitepaper delineates the core mission, structural framework, and methodological approaches of the LTER Network. We detail how its integrated research themes, long-term experiments, and rigorous data management protocols generate the predictive understanding necessary to address complex environmental challenges. By providing a comprehensive guide to the LTER's operational and philosophical tenets, this document aims to illustrate its critical role in advancing fundamental ecological theory and informing evidence-based policy and resource management.

Ecology as a discipline has historically been constrained by the practical limitations of short-term funding cycles and localized studies. However, critical ecological processes—including population dynamics of long-lived species, ecosystem recovery from disturbances, and biogeochemical cycling—unfold over timespans that dwarf typical research grants [1]. The LTER Network was conceived to overcome this mismatch, founded on the recognition that unraveling the principles of ecological science "frequently involves long-lived species, legacy influences, and rare events" [1] [3].

For over four decades, the network has provided the scientific infrastructure—sustained observations, well-documented experiments, and curated data archives—required to observe these slow and often infrequent processes. The LTER network now comprises more than two dozen field sites representing a vast diversity of global habitats, including coral reefs, deserts, estuaries, forests, alpine and Arctic tundra, and urban areas [2]. This breadth enables comparative studies across biomes, allowing scientists to distinguish site-specific phenomena from general ecological principles.

Vision, Mission, and Strategic Goals

The LTER Network is guided by a cohesive strategic framework that aligns its scientific activities with broader societal benefits.

- Vision: LTER envisions a society in which exemplary science contributes to the advancement of the health, productivity, and welfare of the global environment, which in turn advances the health, prosperity, welfare, and security of the nation [1] [4].

- Mission: To provide the scientific community, policy makers, and society with the knowledge and predictive understanding necessary to conserve, protect, and manage the nation’s ecosystems, their biodiversity, and the services they provide [1] [4].

This mission is operationalized through six primary goals [1] [3]:

- Understanding: To understand a diverse array of ecosystems at multiple spatial and temporal scales.

- Synthesis: To create general knowledge through long-term, interdisciplinary research, synthesis of information, and development of theory.

- Outreach: To reach out to the broader scientific community, natural resource managers, policymakers, and the general public.

- Education: To promote training and educate a new generation of scientists.

- Information: To create well-designed and well-documented databases.

- Legacies: To create a legacy of well-designed and documented long-term observations, experiments, and archives for future generations.

Core Research Themes and Framework

LTER science is structured around a set of core research themes that facilitate cross-site comparison and integration. Initially five, the themes have expanded to include critical human-dimension components.

Table 1: Core LTER Research Themes and Definitions

| Theme | Definition & Research Focus |

|---|---|

| Primary Production | Plant growth forms the base of the food web. Research focuses on the patterns and controls of primary production that determine the amount and kind of animal life an ecosystem can support [3]. |

| Population Studies | Examines how populations of plants, animals, and microbes change in space and time, thereby moving resources and restructuring ecological systems [3]. |

| Movement of Organic Matter | Focuses on the decomposition of organic matter and its movement through the ecosystem, a critical process for nutrient recycling and food web dynamics [3]. |

| Movement of Inorganic Matter | Investigates the cycling of nitrogen, phosphorus, and other mineral nutrients through the ecosystem via decay and disturbances like fire and flood [3]. |

| Disturbance Patterns | Studies how disturbances such as storms, fires, and floods periodically reorganize ecosystem structure, enabling significant changes in plant and animal communities [3]. |

| Land Use and Land Cover Change | An emergent theme examining human impacts on land use and land-cover change, particularly in urban systems, and relating these effects to ecosystem dynamics [3]. |

| Human-Environment Interactions | An emergent theme monitoring the effects of human-environmental interactions, developing tools for socio-economic and ecosystem data integration [3]. |

Methodological Approaches: The LTER Experimental Paradigm

LTER sites employ a multi-pronged methodological approach to investigate the core themes, ensuring scientific rigor and relevance.

Integrated Research Approaches

Research at LTER sites typically integrates three complementary strategies [5]:

- Historical Studies: Paleoecology and archival research to understand past conditions and dynamics.

- Monitoring and Observation: Intensive, long-term measurements of current ecosystem structure and function.

- Experimental Manipulations: Field experiments to test hypotheses about ecosystem responses to controlled perturbations under realistic conditions.

The Workflow of LTER Science

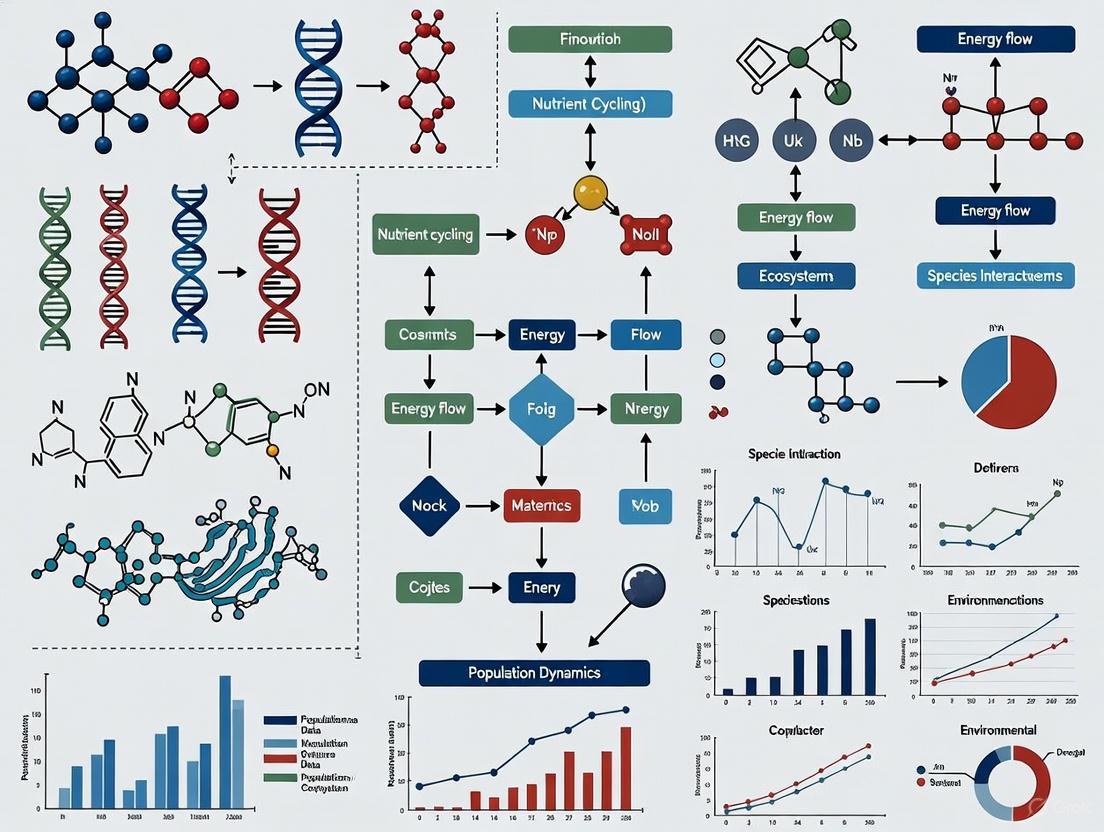

The following diagram illustrates the integrated and cyclical workflow that characterizes research at LTER sites, from foundational data collection to societal impact.

Case Study: The Value of Long-Term Experiments

The Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest LTER provides a seminal example of the program's impact. Beginning in the 1960s, long-term monitoring of precipitation and stream chemistry revealed a previously unknown environmental crisis: acid rain was damaging forest ecosystems [6]. This LTER-generated evidence was pivotal and directly informed the 1990 Clean Air Act Amendments [6]. This case demonstrates how sustained, place-based research provides the credible data necessary for effective environmental legislation.

Data Management: The Backbone of LTER

The value of the LTER Network is inextricably linked to its robust and forward-thinking data management philosophy. The network is committed to making data available online with as few restrictions as possible, adhering to the FAIR principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reproducible) [3] [7].

Table 2: LTER Data Repositories and Their Functions

| Repository | Primary Function & Role |

|---|---|

| Environmental Data Initiative (EDI) | The main repository for LTER data, EDI curates and maintains well-documented, high-quality data packages from LTER sites and other environmental science programs [7]. |

| Regional/Disciplinary Repositories (e.g., Arctic Data Center, BCO-DMO) | Host LTER data in a disciplinary context, making it accessible to specific scientific communities [7]. |

| DataONE Federation | Provides a comprehensive search interface for discovering public LTER data across multiple member nodes and repositories [7]. |

| Local Site Catalogs | Maintained by individual LTER sites, these often include LTER and non-LTER data in a format most usable for site-based researchers, sometimes including pre-publication data [7]. |

Each LTER site employs a dedicated Information Manager who is responsible for documenting, quality-checking, and archiving data in these public repositories [3] [7]. This professional community ensures data are not only preserved but are also accompanied by metadata that makes them interpretable and reusable for future synthetic studies, often to answer questions unanticipated at the time of collection [7].

Essential Research Reagents and Infrastructure

The following table details key infrastructure and "research reagents" that are fundamental to conducting long-term ecological research at LTER sites.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Long-Term Ecological Research

| Item | Function in LTER Research |

|---|---|

| Sensor Networks | Automated, continuous collection of physical (e.g., temperature, PAR) and chemical (e.g., CO₂, nitrate) data at high temporal resolution across a landscape. |

| Weather Stations | Provide long-term, on-site meteorological records (precipitation, temperature, wind, humidity) essential for interpreting ecological patterns. |

| Eddy Covariance Towers | Measure the exchange of carbon dioxide, water vapor, and energy between the ecosystem and the atmosphere to quantify net ecosystem production. |

| Exclosure Experiments | Large-scale physical structures (e.g., fences, snow fences) to experimentally manipulate biotic (herbivore access) or abiotic (snow depth) factors. |

| Plot Networks | Permanently marked and georeferenced field plots for long-term, consistent censusing of plant and animal populations and soil sampling. |

| Specimen Archives | Physical libraries of vouchered plant, animal, and soil samples that provide a historical record for future genetic, isotopic, or morphological analysis [3]. |

| Nutrient Addition Plots | Long-term experimental plots receiving standardized nutrient (e.g., N, P) treatments to study nutrient limitation and biogeochemical cycles. |

| Standardized Taxonomic Keys | Essential reagents for ensuring consistent species identification across decades and by different researchers, protecting data integrity. |

The LTER Network represents a unique and vital enterprise in modern science. It transcends the limitations of the "snapshot" study by maintaining a long-term, place-based, and multidisciplinary research presence across a network of representative ecosystems. Its core mission—to generate the knowledge and predictive understanding needed to manage and protect ecosystems—is achieved through a steadfast commitment to integrated core themes, rigorous experimentation, and the stewardship of a priceless legacy of long-term data. As environmental challenges grow in complexity and scale, the foundational research conducted by the LTER Network will only increase in its value to science, policy, and society.

Understanding complex ecosystems requires more than brief observational snapshots; it demands a commitment to observing ecological processes as they unfold over decades. Short-term studies, while valuable for identifying immediate phenomena, often fail to capture the slow processes, rare events, and complex feedback loops that fundamentally govern ecosystem structure and function. The Long Term Ecological Research (LTER) Network, established by the U.S. National Science Foundation, was created specifically to address these limitations through sustained investigation across diverse ecosystems [8]. This network represents a fundamental shift in ecological research methodology, moving beyond temporary observation to embedded, long-term investigation that can reveal patterns invisible to short-term studies.

The LTER Network comprises over 2,000 researchers working across 28 sites [9] [8], from the McMurdo Dry Valleys in Antarctica to tropical forests in Puerto Rico [8]. This collaborative framework enables researchers to apply standardized approaches including long-term observation, experiments, and modeling to understand how ecological systems function over extended temporal and spatial scales [9]. The knowledge generated through this work provides the scientific foundation necessary to conserve, protect, and manage ecosystems, their biodiversity, and the essential services they provide to society [10].

Theoretical Framework: Ecological Processes Across Temporal Scales

Ecological processes operate across vastly different time scales, from the instantaneous photosynthesis in leaves to the centennial shifts in climate and species composition. The LTER Network's research design explicitly acknowledges this multi-scalar nature of ecological dynamics, focusing on five core areas of investigation: primary production, population dynamics, organic matter accumulation, nutrient cycling, and disturbance patterns [8]. Each of these areas contains elements that manifest over different timeframes, making them particularly unsuitable for brief investigation.

The Problem of Transient Dynamics

Ecosystems rarely exist in steady-state conditions but instead are frequently in states of recovery from past disturbances or adjusting to changing environmental conditions. Short-term studies conducted during these transitional periods can yield misleading conclusions about long-term trends and stable relationships. For instance, an investigation of nutrient cycling immediately following a fire event would capture fundamentally different dynamics than one conducted a decade later during ecosystem recovery. The LTER approach allows researchers to distinguish between temporary fluctuations and genuine trends by maintaining observation through multiple cycles of disturbance and recovery.

Table: Ecological Processes and Their Characteristic Time Scales

| Ecological Process | Characteristic Time Scale | Short-Term Study Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Nutrient Cycling | Seasonal to decadal | Misses interannual variability and long-term accumulation/ depletion trends |

| Population Dynamics | Annual to multi-generational | Fails to capture population responses to rare events and climate shifts |

| Succession | Decadal to centennial | Only reveals initial stages, missing climax communities and transition dynamics |

| Disturbance Regimes | Event-driven to centennial | Unlikely to observe full range of natural variation and recovery processes |

| Evolutionary Adaptation | Multi-generational | Completely invisible without long-term genetic monitoring |

Evidence Base: How Long-Term Data Reveals Hidden Patterns

The value of long-term ecological research becomes evident when examining specific cases where extended datasets have revealed patterns that contradict or complicate conclusions drawn from shorter studies. Across the LTER Network, numerous examples demonstrate how sustained observation has transformed our understanding of ecological processes.

Documenting Ecosystem Responses to Press and Pulse Disturbances

At the Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest LTER, long-term monitoring of sugar maple seedlings revealed unexpected responses to watershed calcium amendment treatments. Data collected in 2003 and 2004 showed differences in seedling heights between calcium-treated and reference watersheds, providing insights into soil acidification recovery processes that would be invisible in a single-year study [10]. Similarly, at the Luquillo LTER, stream chemistry data captured the impact of hurricanes on water quality, documenting both the immediate effects and the extended recovery period [10]. These datasets exemplify how LTER research captures both "pulse" disturbances (discrete events like hurricanes) and "press" disturbances (continuous pressures like acid deposition).

At the North Temperate Lakes LTER, ice cover records spanning from 1853 to 2019 have provided crucial evidence of climate change impacts on freshwater systems [10]. This extraordinary temporal depth allows researchers to distinguish natural variability from anthropogenic trends and to develop predictive models of how lakes will respond to continued warming. The length of this dataset is particularly valuable as it predates significant human-caused climate change, providing a critical baseline against which to measure recent alterations.

Cross-Site Synthesis and Comparative Analysis

The power of LTER data is magnified through cross-site comparisons that reveal broader ecological principles. The Network coordinates data collection and management standards that enable researchers to conduct synthetic studies across multiple ecosystems [9] [7]. For example, the lterdatasampler R package contains curated datasets from multiple LTER sites, specifically designed for educational use [10]. These standardized datasets allow students and researchers to compare ecological patterns across diverse biomes, from the Arctic to the tropics.

Table: Representative LTER Datasets and Their Research Applications

| LTER Site | Dataset | Temporal Scope | Research Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Andrews Forest | Aquatic vertebrates | 1987-present | Length-mass relationships, effects of forest management on aquatic ecosystems [10] |

| Arctic | Daily meteorological data | 1988-present | Climate change impacts, seasonality studies, forecasting [10] |

| Hubbard Brook | Sugar maple seedlings | 2003-2004 | Soil acidification recovery, calcium treatment effects [10] |

| North Temperate Lakes | Ice cover phenology | 1853-2019 | Climate change impacts on freshwater systems, phenological shifts [10] |

| Konza Prairie | Bison mass records | Ongoing | Animal growth models, grazing effects on prairie ecosystems [10] |

| Plum Island | Fiddler crab morphology | 2016 | Latitudinal gradients, Bergmann's Rule validation [10] |

Methodological Protocols: Implementing Long-Term Ecological Research

The LTER Network has developed sophisticated methodological protocols to ensure that data collection remains consistent, comparable, and sustainable across decades of research. These protocols encompass everything from field data collection to information management and sharing.

Data Management and Curation Protocols

A cornerstone of the LTER approach is its commitment to high-quality, well-documented, and publicly accessible data. Each LTER site employs an Information Manager who ensures that data are reviewed for errors and inconsistencies and thoroughly documented [7]. The Network maintains several pathways for data access:

- Environmental Data Initiative (EDI): The main repository for LTER data, EDI curates and maintains data from many environmental science research programs [7].

- Regional Repositories: LTER data are also available through disciplinary or regional repositories such as the Biological and Chemical Oceanography Data Management Office (BCO-DMO), the Arctic Data Center, and others [7].

- Local Site Catalogs: Many LTER sites maintain local data catalogs that include both LTER and non-LTER data, often presented in ways most usable for site-based researchers [7].

The LTER data management philosophy emphasizes making data available with as few restrictions as possible, recognizing that freely available data are often reused to answer unexpected questions years after their initial collection [7]. This approach has established the LTER Network as a leader in promoting the FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) principles for scientific data management.

Experimental Design for Long-Term Studies

LTER research combines observational studies with large-scale, long-term experiments to disentangle complex ecological interactions. The Kellogg Biological Station LTER, for example, maintains multiple long-term experiments including the Main Cropping System Experiment (MCSE) that compares annual crop systems, perennial systems, and unmanaged communities [11]. This experimental design allows researchers to examine how different management approaches affect productivity, nutrient cycling, and biodiversity over decades.

Similarly, the Konza Prairie LTER maintains watershed-level experimental treatments involving different fire return intervals and grazing regimes. These experimental manipulations, maintained over decades, have revealed the complex interactions between disturbance regimes and grassland ecosystem structure and function. Such research would be impossible through short-term experimentation, as many ecological responses unfold over timescales that exceed traditional funding cycles.

LTER Methodological Framework

Conducting successful long-term ecological research requires specialized tools and approaches that differ in important ways from those used in short-term studies. The following research reagents and resources represent essential components of the LTER toolkit.

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Long-Term Ecological Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Function in LTER Research |

|---|---|---|

| Data Repositories | Environmental Data Initiative (EDI) [7] | Primary repository for LTER data, ensuring long-term preservation and access |

| Data Synthesis Tools | DataONE [7] | Federated search across multiple ecological data repositories |

| Analytical Programming | R package lterdatasampler [10] |

Provides curated LTER datasets for educational and exploratory analysis |

| Information Management | LTER Information Managers [7] | Site-based experts ensuring data quality, documentation, and standards compliance |

| Cross-site Communication | LTER Network Office [9] | Coordinates research priorities, standards, and synthesis activities across sites |

| Meteorological Instrumentation | Automated weather stations [10] | Standardized collection of long-term climate data across sites |

| Species Monitoring Protocols | Standardized trapping, counting, and identification methods [10] | Consistent tracking of population dynamics across temporal scales |

Technological Frontiers: Emerging Approaches in Long-Term Research

The LTER Network continues to evolve its methodological approaches, incorporating new technologies and analytical frameworks to enhance the value of long-term data. Several emerging approaches show particular promise for advancing understanding of complex ecosystems.

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Applications

The LTER community is actively exploring applications of Generative AI (GenAI) and other artificial intelligence approaches to enhance research workflows. These tools show promise for multiple aspects of ecological research, including data quality checks, analysis, visualization, metadata generation, and knowledge management [12]. For example, AI tools can help identify anomalies in long-term datasets, generate standardized metadata, and synthesize information from diverse sources.

However, the integration of AI into ecological research also presents significant challenges, including content risks (hallucinations, misinformation), cultural risks (undermining scientific integrity), and environmental risks (substantial energy demands) [12]. The LTER community emphasizes responsible use of these tools, including careful verification of outputs and consideration of ethical implications [12].

Standardized Data Packaging and Analysis

The development of specialized software tools represents another frontier in long-term ecological research. The lterdatasampler R package exemplifies this approach, providing standardized access to curated datasets from multiple LTER sites [10]. Such tools lower barriers to engaging with long-term data, particularly in educational contexts, and promote reproducible analytical workflows.

Similarly, the LTER community has developed ltertools, an R package created by and for the LTER community to streamline common analytical tasks [7]. These specialized software resources enhance the utility of long-term datasets and facilitate cross-site comparisons that can reveal broader ecological principles.

LTER Research Workflow

The critical shift from short-term investigations to long-term ecological research represents more than merely extending observation periods; it constitutes a fundamental transformation in how we understand and study complex ecosystems. The LTER Network has demonstrated repeatedly that processes invisible in short-term studies often determine ecological outcomes over human lifespans and beyond. From climate change impacts on ice cover to the slow recovery of ecosystems from acid deposition, long-term research provides insights essential for both scientific understanding and effective environmental management.

As environmental challenges become increasingly complex and pressing, the need for robust long-term ecological data becomes ever more critical. The research methodologies, data management practices, and collaborative frameworks developed by the LTER Network provide an essential foundation for addressing these challenges. By maintaining this commitment to understanding ecological processes across extended temporal scales, the scientific community can develop the knowledge necessary to conserve and protect the ecosystems upon which human society depends.

The Long-Term Ecological Research (LTER) network represents a transformative approach to ecology that emphasizes sustained observation and experimentation to understand ecological processes that play out over decades and centuries. Initiated by the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) in 1980, the LTER program was founded on the recognition that many critical ecological phenomena—from forest succession to nutrient cycling—operate on timescales far longer than typical research grants [13]. This paradigm challenged the prevailing model of short-term ecological studies and created an infrastructure for sustained investigation at individual sites, while simultaneously building a network for cross-site comparison and synthesis.

The core innovation of LTER lies in its dual emphasis on place-based research and network-level science. Individual sites build deep knowledge of specific ecosystems, while the network facilitates comparison across diverse biomes and environmental conditions. This approach has revealed patterns and processes invisible to shorter-term studies, such as the complex responses of ecosystems to climate change, the long-term impacts of disturbance regimes, and the slow unfolding of biotic interactions [14]. Over more than four decades, the LTER network has expanded from an initial set of six sites to encompass 26 active sites across the United States, including diverse ecosystems from polar regions to tropics, and from remote wilderness to urban centers [9].

The success of the U.S. LTER network inspired the creation of the International LTER (ILTER) network, which now operates as a network of country-based networks focused on long-term, place-based research from an ecosystem perspective [15]. With 44 member networks and over 800 sites in almost every biome on Earth, ILTER has globalized the LTER approach, enabling research on planetary-scale ecological challenges [15]. Both networks share a commitment to data preservation, sustainability, and access, recognizing that long-term datasets are invaluable resources for detecting change, testing theories, and informing policy.

Historical Development and Key Milestones

The Formative Years of LTER

The LTER network has evolved through distinct phases since its establishment, with key transitions reflected in its governance, scientific priorities, and physical composition. The 1980s marked the network's formation, with the first sites selected for their representative ecosystems and potential for long-term study. During the 1990s, the network matured, developing standardized measurement protocols and information management systems that enabled cross-site comparison. The 2000s witnessed a strategic expansion into new ecosystem types and the beginnings of international coordination, while the 2010s saw increased emphasis on synthesis and network-level science [14].

Significant transitions have occurred in the network's leadership and organizational structure. Major governance changes were implemented in 2006 when a new structure consisting of a Science Council and an Executive Board was approved [14]. This period also saw the development of formal bylaws for the LTER Network in 2003, providing a framework for decision-making and collaboration [14]. Leadership transitions have been regular features of the network's history, with notable chairs including Diane McKnight elected in 2019, Peter Groffman assuming the role in 2014 after Scott Collins' resignation, and Phil Robertson elected in 2007 [14].

The network's composition has dynamically changed over time, with sites added and retired based on scientific priorities and funding decisions. Recent additions have particularly emphasized marine ecosystems, with three new LTER sites receiving NSF funding in 2017: Northeast U.S. Shelf (NES), Northern Gulf of Alaska (NGA), and Beaufort Lagoon Ecosystem (BLE) [14]. Conversely, several sites have concluded their LTER activities, including Coweeta LTER officially ending in 2021 and the Baltimore Ecosystem Study not renewed in 2019 [14].

Expansion and Internationalization

The international expansion of LTER began in earnest in the early 2000s, with the formation of the U.S. ILTER Committee in 2003 [14]. This development recognized the value of global comparisons for understanding ecological processes operating at broad scales. A significant milestone occurred in 2013 when the U.S. and French LTER networks signed a Memorandum of Understanding, committing both networks to site and scientist collaborations [14]. This formal agreement exemplified the growing importance of international partnerships in addressing global environmental challenges.

The European LTER network (LTER-Europe) was established in 2007 and has since grown to include 26 national networks as of 2025 [16]. LTER-Europe has been instrumental in advancing the integration of social and ecological sciences through the development of the Long-Term Socio-Ecological Research (LTSER) platform concept [16]. These platforms represent a significant evolution from traditional LTER sites by encompassing larger areas (up to 10,000 km²) and explicitly incorporating human dimensions through networking of actor groups, data management, and communication services [16].

Table: Major Historical Milestones in LTER and ILTER Development

| Year | Event | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| 1980 | U.S. LTER Program created by NSF | Established the first coordinated long-term ecological research network [13] |

| 2000 | Three new coastal LTER sites join network | Expanded research into critical coastal ecosystems [14] |

| 2003 | U.S. ILTER Committee formed | Formalized international engagement and collaboration [14] |

| 2007 | LTER-Europe founded | Created regional structure for European collaboration [16] |

| 2013 | U.S.-French LTER MOU signed | Exemplified growing international partnerships [14] |

| 2017 | Three new marine LTER sites funded | Significantly expanded marine ecosystem research [14] |

| 2021 | Minneapolis-St. Paul urban LTER established | Continued emphasis on human-dominated ecosystems [14] |

Recent Developments and Current Status

The most recent decade has been characterized by both challenges and achievements. The 40th anniversary of the LTER Network in 2020 coincided with the global COVID-19 pandemic, which shut down nearly all research for the summer of 2020 and continued to affect vulnerable polar sites into the following field season [14]. Despite these disruptions, the network has continued to evolve, with a decadal review committee formed and charged by NSF to review the last decade of the Network's activities in 2020 [14].

Recent years have seen important developments in network infrastructure and coordination. The LTER Network Office received continued funding for operation at the National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis at UC Santa Barbara in 2019, while the Environmental Data Initiative received continued funding for operation at the University of Wisconsin and the University of New Mexico [14]. These investments reflect the ongoing commitment to supporting the network's scientific and data management needs.

The international network continues to expand its global reach, with ILTER's 2024 Open Science Meeting held in Xishuangbanna, China, and future meetings planned for Bariloche, Argentina in 2027 [17]. These gatherings facilitate the exchange of knowledge regarding the latest developments in long-term ecosystem research and strengthen connections among researchers worldwide.

Organizational Structure and Network Composition

Governance and Coordination

The LTER and ILTER networks have developed sophisticated governance structures to coordinate activities across multiple scales while maintaining scientific autonomy at individual sites. The U.S. LTER network operates through a framework established by its Executive Board and Science Council, which provide strategic direction and scientific coordination respectively [14]. This structure was formalized in 2006 when a new governance model was approved by the LTER Coordinating Committee, replacing earlier more informal arrangements [14].

Day-to-day operations are supported by the LTER Network Office (LNO), which has been housed at various institutions throughout the network's history, most recently at the National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis at UC Santa Barbara [14]. The LNO facilitates communication, education and outreach, planning, and synthesis activities across the network. Additional specialized support comes from the Environmental Data Initiative (EDI), which operates from the University of Wisconsin and the University of New Mexico and is responsible for data management infrastructure [14].

At the international level, ILTER functions as an "umbrella organization" encompassing national LTER networks [16]. Each member network maintains its own governance structure while participating in ILTER activities. LTER-Europe, as one of the regional groups of ILTER, has two seats in the ILTER Executive Committee and has provided leadership including the ILTER co-chair and secretary positions [16]. This distributed governance model allows for both global coordination and regional adaptation to specific scientific priorities and funding environments.

Site Classifications and Research Facilities

The LTER and ILTER networks encompass diverse research facilities classified according to their spatial scale and research focus. The basic unit is the LTER site ("traditional" LTER site), which is a facility of limited size (up to 10 km²) comprising mainly one habitat type and form of land use [16]. Activities at these sites concentrate on small-scale ecosystem processes and structures, including biogeochemistry, selected taxonomic groups, primary production, and disturbances [16].

A significant innovation in Europe has been the development of LTSER platforms (Long-Term Socio-Ecological Research platforms). These are modular LTER facilities consisting of sites located in an area with defined boundaries, typically covering up to 10,000 km² [16]. Beyond the physical research component, LTSER platforms provide multiple services including networking of actor groups (e.g., researchers, local stakeholders), data management, communication, and representation [16]. The elements of LTSER platforms represent the main habitats, land use forms, and practices relevant for the broader region and cover all scales and levels relevant for LTSER from local to landscape scales [16].

Table: Classification of LTER Research Facilities

| Facility Type | Spatial Scale | Primary Focus | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| LTER Site | Up to 10 km² | Ecosystem processes and structures | Single habitat type; focus on biogeochemistry, primary production, selected taxa, disturbances [16] |

| LTSER Platform | Up to 10,000 km² | Socio-ecological interactions | Multiple habitats and land uses; includes physical component and management/services component; represents economic and social units [16] |

These facility types form the basis for the construction of the emerging eLTER Research Infrastructure (eLTER RI) in Europe, which is currently in the process of selecting participating sites and platforms [16]. The formalization of these categories is an ongoing activity within the European LTER process, with further specifications developed in other advanced national networks including South Africa's SAEON, Australia's TERN, and China's CERN [16].

Scientific Framework and Methodologies

Core Research Principles and Approaches

The scientific framework of LTER and ILTER is built upon several foundational principles that distinguish it from other ecological research approaches. Long-term observation forms the bedrock of the network's activities, enabling the detection of slow processes and rare events, the quantification of variability, and the separation of directional change from natural oscillation [13]. This temporal dimension is complemented by a place-based approach that recognizes the importance of context and history in shaping ecological patterns and processes.

A second key principle is cross-site comparison, which allows researchers to distinguish site-specific phenomena from general principles operating across multiple ecosystems [15]. The network deliberately encompasses diverse biomes and environmental conditions to facilitate these comparisons. This approach has been formalized through the development of standardized protocols for measuring core variables, enabling data compatibility across sites and through time [18].

More recently, the networks have embraced socio-ecological integration as a core principle, particularly through the LTSER platform concept [16]. This approach recognizes that most contemporary ecosystems are influenced by human activities and that understanding their dynamics requires integrating social and ecological data. The Eisenwurzen LTSER platform in Austria exemplifies this approach, having collected and evaluated 117 socio-ecological datasets spanning more than five decades (1970–2023) to understand human-environment interactions [19].

Data Management and Synthesis Protocols

The LTER and ILTER networks have developed sophisticated data management infrastructures to ensure the preservation, quality, and accessibility of long-term datasets. The Environmental Data Initiative (EDI) serves as the primary repository for U.S. LTER data, providing tools for data submission, quality checking, and discovery [14]. Internationally, the Dynamic Ecological Information Management System – Site and dataset registry (DEIMS-SDR) serves as a comprehensive metadata portal containing information on ILTER sites worldwide [15] [16].

A critical methodology that has emerged within the networks is synthesis working groups, which bring together researchers from multiple sites to address cross-cutting questions. Since 2015, the LTER Network has formally funded Synthesis Working Groups to tackle questions requiring integration of data from multiple sites and disciplines [14]. These groups follow structured protocols for data identification, harmonization, analysis, and publication that have proven effective for generating new insights from existing data.

The Climate-Hydrology Synthesis Working Group exemplifies this approach, having developed specific protocols for climate and streamflow trend analysis across LTER sites [18]. Their methodology includes:

- Data Identification and Harvesting: Identifying daily climate and streamflow data suitable for long-term trend analysis (1950-2012) and harvesting these data into climDB/hydroDB, a web harvester and data warehouse that provides uniform access through a single portal [18].

- Data Quality Control: Checking climate data for discontinuities due to changes in instrumentation, physical surroundings, data collection methods, or data archiving [18].

- Standardized Trend Analysis: Conducting rigorous, standardized trend analyses using consistent statistical approaches across sites [18].

- Comparison and Synthesis: Sharing, comparing, and interpreting climate and streamflow trends across the full collection of LTER sites to identify broader patterns [18].

Distributed Experiments and Emerging Methodologies

In recent years, LTER and ILTER networks have increasingly served as platforms for distributed experiments in which a standardized protocol is implemented across multiple sites. These experiments represent a powerful bridge between continental-scale monitoring and in-depth site-based studies [15]. Examples include:

- DroughtNet: A global network studying ecosystem sensitivity to drought by imposing standardized rainfall manipulation experiments at over 100 sites worldwide.

- NutNet (Nutrient Network): A coordinated grassland experiment examining impacts of nutrient enrichment across more than 130 sites globally.

- DIRT (Detrital Input Removal and Trenching): A long-term experiment manipulating litter inputs and root activity to study soil carbon dynamics.

- Tea Bag Index: A simple standardized method using tea bags as standardized litter bags to measure decomposition rates across ecosystems.

These distributed experiments leverage the existing infrastructure of research sites while enabling tests of ecological principles across diverse environmental conditions. The methodology typically involves developing a simple, cost-effective protocol that can be implemented consistently across sites with varying resources and expertise, followed by coordinated data analysis that examines both general patterns and context dependence [15].

Research Tools and Infrastructure

Field Instrumentation and Monitoring Systems

Long-term ecological research requires robust, reliable instrumentation capable of operating continuously across seasonal and interannual time scales. The LTER and ILTER networks employ a diverse suite of monitoring technologies selected for their durability, accuracy, and compatibility with network-wide data standards. While specific instruments vary by site and research focus, several core technologies are widely deployed across the networks.

Environmental sensor networks form the technological backbone of most LTER sites, providing continuous measurements of meteorological, hydrological, and soil parameters. These typically include automated weather stations measuring temperature, precipitation, humidity, solar radiation, and wind speed; stream gauges monitoring discharge, temperature, and conductivity; and soil sensors tracking moisture, temperature, and in some cases nutrient availability. Data from these sensors are typically logged automatically and transmitted to central databases at regular intervals.

Biometric monitoring represents another essential component, with standardized protocols for measuring vegetation structure and composition, population dynamics of key species, and ecosystem processes such as primary production and decomposition. These measurements often combine technologically advanced approaches (such as automated camera systems for phenological monitoring or lidar for vegetation structure) with traditional field methods to maintain continuity with long-term datasets.

Table: Essential Research Tools in LTER/ILTER Investigations

| Tool Category | Specific Technologies | Primary Functions | Data Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atmospheric Monitoring | Eddy covariance towers, weather stations, precipitation gauges | Measure greenhouse gas fluxes, meteorological variables | Climate trend analysis, ecosystem-atmosphere exchange [20] |

| Hydrological Instruments | Stream gauges, water quality sensors, soil moisture probes | Monitor discharge, water chemistry, soil hydrology | Hydrological trend analysis, nutrient cycling studies [18] |

| Biological Survey Tools | Vegetation plots, camera traps, acoustic monitors, dendrometers | Quantify species distribution, abundance, phenology, growth | Biodiversity assessment, population dynamics, phenological shift detection |

| Remote Sensing Platforms | Satellites, UAVs, aerial photography | Landscape-scale monitoring of vegetation, land cover, topography | Land use change detection, habitat mapping, disturbance assessment [20] |

| Data Management Systems | DEIMS-SDR, EDI Data Portal, PASTA | Data preservation, metadata cataloging, data discovery and access | Data synthesis, cross-site comparison, quality assurance [14] [15] |

Cyberinfrastructure and Data Systems

The LTER and ILTER networks have invested significantly in cyberinfrastructure to support the management, preservation, and sharing of long-term data. The Environmental Data Initiative (EDI) serves as the primary data repository for U.S. LTER sites, providing tools for data submission, quality assurance, and discovery [14]. EDI utilizes the PASTA (Provenance Aware Synthesis Tracking Architecture) software framework, which has expanded to serve the broader Division of Environmental Biology community [14].

At the international level, the Dynamic Ecological Information Management System – Site and dataset registry (DEIMS-SDR) functions as a comprehensive catalog for ILTER sites, documenting site characteristics, research projects, investigators, and available data [15] [16]. DEIMS-SDR enables researchers to search for sites, sensors, or activities meeting specific criteria and facilitates connections between potential collaborators across the global network.

The networks have also developed specialized databases for particular data types or synthesis activities. Examples include the LTER NIS Data Portal released in 2013 for accessing LTER site data, and the earlier Clim/HydroDB database transferred from Oregon State University to the LTER Network Office in 2009 [14]. These specialized resources complement the general data repositories by providing tailored access to specific data types commonly used in cross-site research.

Significant Research Findings and Applications

Ecological Insights from Long-Term Studies

The extended temporal perspective of LTER research has yielded fundamental insights into ecological dynamics that would be inaccessible through shorter-term studies. At individual sites, long-term observations have revealed complex ecosystem responses to environmental change that often contradict expectations based on short-term experiments. For example, research at multiple LTER sites has demonstrated that initial ecosystem responses to perturbations such as drought, fertilization, or species invasions frequently differ substantially from longer-term trajectories due to compensatory mechanisms, evolutionary adaptations, and changing biotic interactions.

Cross-site syntheses have identified general principles governing ecosystem structure and function across diverse environmental conditions. The Climate-Hydrology Synthesis Working Group, for instance, has conducted systematic analyses of climate and streamflow trends across LTER sites, revealing coherent regional patterns in hydroclimatic change despite substantial site-to-site variability [18]. These analyses provide crucial context for interpreting ecological responses to climate change at individual sites and offer insights into the mechanisms underlying geographical variation in vulnerability.

Research within the networks has also advanced understanding of ecological connectivity across spatial scales. Studies examining relationships between pattern and process from local to landscape scales have been particularly facilitated by the LTSER platform approach, which explicitly incorporates multiple spatial scales within its design [16]. This work has demonstrated how fine-scale processes can aggregate to produce regional patterns, and how broad-scale drivers can constrain local dynamics.

Policy and Management Applications

The long-term perspectives provided by LTER and ILTER research have proven invaluable for environmental management and policy development. The networks' data have informed management of natural resources by providing context for interpreting shorter-term monitoring results and identifying the range of natural variability against which human impacts can be assessed [20]. For instance, long-term data from LTER sites have been used to set biologically meaningful standards for air and water quality, to develop sustainable harvest levels for fisheries and forests, and to design effective conservation strategies for threatened species and ecosystems.

The socio-ecological research approach pioneered particularly within LTER-Europe has advanced the practice of adaptive management by creating structures for ongoing collaboration between researchers and stakeholders [20]. The Climate Ecological Observatory for Arctic Tundra (COAT) in the Norwegian Arctic exemplifies this approach, using a food-web framework to design monitoring programs that integrate management interventions within the conceptual models guiding long-term research [20]. Such collaborations become particularly productive when researchers and managers work together over time, developing common understanding and mutual trust [20].

LTER research has also contributed to environmental policy at regional, national, and international levels. The networks' data on trends in ecosystem condition have informed legislation and international agreements addressing issues including air pollution, climate change, and biodiversity conservation. The emphasis on making data publicly accessible has ensured that policy makers have access to the best available science when making decisions with long-term consequences for ecosystems and human communities.

Future Directions and Emerging Challenges

Scientific Priorities and methodological Evolution

The LTER and ILTER networks continue to evolve in response to emerging scientific questions and methodological opportunities. Several priority areas are shaping the networks' trajectories, including:

Enhanced integration of social and ecological sciences: The success of LTSER platforms in Europe is driving efforts to more fully incorporate human dimensions into LTER research worldwide [19]. This includes developing standardized socio-ecological variables, improving methods for integrating qualitative and quantitative data, and creating frameworks for conceptualizing and modeling feedbacks between social and ecological systems [19]. The Eisenwurzen LTSER platform has demonstrated the value of collecting and evaluating socio-ecological datasets spanning multiple decades, while also highlighting challenges in accessing long-term series for certain variables such as consumption, livestock, and regional economics [19].

Upscaling and intercomparison: As global connectivity increases, there is growing recognition of the need to better incorporate multiple scales in socio-ecological research [20]. eLTER is advancing the analysis of upscaling phenomena in socio-ecological systems, with particular focus on requirements for integrating place-based research in LTSER platforms with national to continental approaches in social ecology [20]. This work addresses the challenge of transferring information between scales in analyzing and modeling socio-ecological systems.

Technological innovation: The networks are increasingly leveraging new technologies including environmental sensor networks, remote sensing platforms, and molecular tools to expand the scope and precision of observations. A particularly promising development is the creation of integrated observatories for studying interactions between Earth's surface and the atmosphere, which would combine measurements of greenhouse gases, atmospheric chemicals, and ecosystems at the same locations [20]. Such observatories would allow more cost-efficient understanding of how the Earth system works by resolving processes or fluxes that satellites cannot detect and providing ground-truthing for satellite data [20].

Structural and Collaborative Developments

The organizational structures of LTER and ILTER are also evolving to meet changing scientific needs and operational challenges. Several developments are likely to shape the networks' future:

Formalization of research infrastructures: In Europe, the eLTER process is advancing toward establishment of a formal eLTER Research Infrastructure (eLTER RI) through the European Strategy Forum on Research Infrastructures (ESFRI) [16] [19]. This formalization will enhance the long-term stability of the network and support more standardized operations across sites. Similar developments are occurring in other regions, including South Africa's SAEON, Australia's TERN, and China's CERN [16].

Strengthened global integration: The ILTER network is working to improve representativeness, particularly in the Americas and the Global South, as evidenced by the planned 2027 Open Science Meeting in Bariloche, Argentina [17]. This focus on broadening geographical participation will enhance the network's capacity to address globally relevant ecological questions and incorporate diverse perspectives and knowledge systems.

Enhanced training and capacity building: The networks are placing increased emphasis on supporting early career researchers and building scientific capacity worldwide. Initiatives such as the ILTER Early Career Researchers Network and virtual training opportunities are expanding access to the skills and knowledge needed for long-term ecological research [17]. These efforts recognize that sustaining long-term research requires continuous engagement of new generations of scientists.

As the LTER and ILTER networks look toward their next decades, they face the challenge of maintaining long-term continuity in observation and experimentation while remaining responsive to rapidly evolving scientific questions and methodological opportunities. Their continued success will depend on sustaining the foundational principles of place-based research, data sharing, and cross-site comparison while adapting to new understandings of ecological complexity and increasing human influence on Earth's systems.

The Long-Term Ecological Research (LTER) program, established by the National Science Foundation (NSF) in 1980, was founded on the recognition that many critical ecological questions cannot be resolved with short-term observations or experiments [3]. Ecological phenomena often involve long-lived species, legacy influences, and rare events, requiring decadal-scale studies to unravel fundamental principles and processes [3] [21]. The LTER network provides the scientific community, policy makers, and society with the knowledge and predictive understanding necessary to conserve, protect, and manage the nation's ecosystems, their biodiversity, and the services they provide [3].

LTER research is characterized by two fundamental components: (1) research located at specific sites chosen to represent major ecosystem types or natural biomes, and (2) emphasis on studying ecological phenomena over long periods of time based on data collected in core areas [22] [21]. This dual approach enables researchers to obtain an integrated, holistic understanding of populations, communities, and ecosystems that would be impossible through individual, short-term investigations [21]. The network currently supports 27 research sites across diverse ecosystems, generating more than 40 years of sustained observations that are publicly available to the scientific community [3] [22].

Conceptual Framework and Core Research Areas

The conceptual framework of LTER research is organized around compelling questions that require uninterrupted, long-term collection, analysis, and interpretation of environmental data [21]. This framework explicitly justifies the long-term questions posited by the research and identifies how data in core areas contribute to understanding these questions while testing major ecological theories and concepts [21]. The common focus on standardized core areas facilitates powerful comparisons across the network's diverse ecosystems [23].

The Original Five Core Themes

Five core research themes have been central to LTER Network science since its inception. Research in these areas requires the involvement of multiple scientific disciplines over long time spans and broad geographic scales [3] [23].

Table 1: Original Five Core Research Themes in LTER

| Core Theme | Research Focus | Ecosystem Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Production | Plant growth as the base component of food webs | Determines the amount and type of secondary productivity (animals) an ecosystem can support [3] |

| Population Studies | Dynamics of plant, animal, and microbial populations in space and time | Understanding how populations move resources and restructure ecological systems [3] |

| Movement of Organic Matter | Decomposition and recycling of dead plants, animals, and organisms | Critical component of nutrient cycling and food web dynamics [3] |

| Movement of Inorganic Matter | Cycling of nitrogen, phosphorus, and other mineral nutrients through decay and disturbance | Understanding how excessive nutrients can have far-reaching harmful effects on environments [3] |

| Disturbance Patterns | Ecosystem reorganization through fire, flood, and other disturbances | Periodic restructuring allows significant changes in plant and animal communities [3] |

Emerging Core Themes

With the addition of urban LTER sites, two additional themes have emerged that have proven relevant across the entire network [3] [23]:

Land Use and Land Cover Change: Examines human impact on land use and land-cover change in urban systems and relates these effects to ecosystem dynamics [23].

Human-Environment Interactions: Monitors effects of human-environmental interactions in urban systems, develops appropriate tools (such as GIS) for data collection and analysis of socio-economic and ecosystem data, and creates integrated approaches to linking human and natural systems in urban environments [23].

Methodological Approaches in LTER

LTER employs sophisticated methodological approaches that integrate long-term observation, experimentation, and modeling to understand ecological processes across multiple spatial and temporal scales.

Long-Term Data Collection Protocols

The value of LTER's long-term data resource is immense, and LTER data managers have been leaders in the movement to ensure ecological data is accessible and usable [3]. Dedicated information managers document and archive LTER data in public repositories, primarily the Environmental Data Initiative (EDI), which has a strong record of serving FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reproducible) data [3]. Data collection follows rigorous protocols established for each core research area to maintain consistency across decades of observation.

Experimental Designs and Cross-Site Synthesis

LTER sites develop and maintain large-scale experiments that provide starting conditions for process-level studies, help parameterize and test models, and spur cross-site synthesis [3]. These experiments are designed to run for multiple years or decades to capture ecological processes that operate over longer timeframes than traditional grant cycles. The network facilitates cross-site interactions that examine patterns or processes over broad spatial scales, enabling researchers to distinguish site-specific phenomena from general ecological principles [21].

Integrating Eco-Evolutionary Dynamics

Recent research highlights the importance of integrating evolutionary biology with ecosystem science to forecast ecosystem outcomes of global change more accurately [24]. Common garden experiments have demonstrated that many species exhibit heritable variation in traits that underlie organismal capacity to respond to global change pressures like warming, elevated CO₂, and nitrogen enrichment [24]. "Resurrection" approaches—combining common garden experiments with predictive ecosystem modeling—examine how trait evolution can alter carbon accumulation and other critical ecosystem processes [24].

Table 2: Key Methodologies for Studying Eco-Evolutionary Dynamics

| Methodology | Application | Research Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Common Garden Experiments | Quantifying heritable trait variation | Demonstrates potential for selection-driven evolution in response to global change pressures [24] |

| Resurrection Ecology | Studying evolution using soil-stored seeds or propagules | Reconstructs century-long records of evolution in response to environmental change [24] |

| Genome-Wide Association Studies | Characterizing genomic architecture of traits | Identifies underlying genetic basis of heritable traits responding to selection [24] |

| Integrated Ecosystem-Evolution Modeling | Joining ecosystem models with models of trait evolution | Provides novel frameworks for investigating how plasticity and evolution shape ecosystem processes [24] |

Data Management and Visualization Standards

Data Management Protocols

The LTER Network has established comprehensive data management protocols to ensure the long-term integrity, accessibility, and usability of ecological data. All LTER data must be made publicly accessible in compliance with NSF data requirements [22] [21]. The network's commitment to the FAIR data principles ensures that decades of ecological observations remain available for future scientific discovery and reanalysis [3].

Effective Data Presentation

Recent research on table design in ecology emphasizes three key principles for effective data communication: (1) aiding comparisons, (2) reducing visual clutter, and (3) increasing readability [25]. Analysis of tables published in ecology journals reveals that most tables have no heavy grid lines and little visual clutter, with clear headers and horizontal orientation [25]. However, most tables fail to adequately support vertical comparison of numeric data. Authors can improve tables through:

- Right-flush alignment of numeric columns typeset with a tabular font

- Clear identification of statistical significance

- Descriptive titles and captions that fully explain table content [25]

LTER research relies on a sophisticated suite of research tools and platforms that enable the collection, integration, and analysis of multimodal ecological data.

Table 3: Essential Research Platforms and Tools for LTER Science

| Platform/Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in LTER Research |

|---|---|---|

| Biodiversity Data Platforms | Various open-access biodiversity databases | Provide species occurrence data, trait data, and taxonomic checklists for cross-site comparisons [26] |

| Environmental Data Repositories | Environmental Data Initiative (EDI) | Primary repository for LTER data, ensuring FAIR data principles and long-term data preservation [3] |

| Data Standards | Darwin Core standards | Enable data standardization, harmonization, and interoperability across diverse datasets [26] |

| Analytical Tools | Species Distribution Models, Machine Learning algorithms | Analyze effects of environmental drivers on biodiversity and predict ecosystem changes [26] |

| Geospatial Tools | Geographic Information Systems (GIS) | Collect and analyze socio-economic and ecosystem data, particularly for human-environment interactions [23] |

Significant Findings and Theoretical Contributions

Over four decades of research, the LTER network has produced transformative insights into ecological dynamics. Long-term experiments continue to reveal cutting-edge ecological processes that can only be gleaned through sustained study [3]. Key contributions include:

Advancing Understanding of Ecosystem Dynamics

LTER research has documented non-linear ecological responses, legacy effects, and complex feedback loops that operate across decadal timescales. This research has been particularly valuable for understanding how ecosystems respond to gradual environmental change as well as discrete disturbance events [3]. The network's long-term datasets have revealed ecological thresholds and regime shifts that would be undetectable in shorter studies.

Integrating Social-Ecological Systems

The addition of urban LTER sites has advanced the development of social-ecological theory by explicitly studying the role of humans in ecological processes [21]. This research examines how human decisions and institutions interact with ecological patterns and processes across multiple scales, from local neighborhoods to regional landscapes.

Informing Global Change Forecasts

Recent work highlights how integrating evolutionary biology with ecosystem science can improve forecasts of ecosystem responses to global change [24]. Studies demonstrate that heritable traits in foundation species can influence ecosystem processes including carbon cycling, carbon storage, nutrient uptake, and nutrient removal [24]. This suggests that evolutionary responses to global change could substantively alter ecosystem properties, with important implications for climate change projections.

Future Directions and Emerging Frontiers

As the LTER Program progresses through its fifth decade, new challenges and opportunities are shaping its research agenda. The network is increasingly focused on understanding ecological processes in the context of rapid global environmental change and developing predictive frameworks that incorporate non-linear dynamics and cross-scale interactions [21].

Emerging frontiers include exploring how ecological and evolutionary processes interact continually through feedbacks, and how these interactions influence ecosystem responses to environmental change [21] [24]. There is growing recognition that important ecological processes are context-dependent and that the effects of environmental change on ecosystem structure and function remain poorly understood [21]. The LTER network is positioned to address these challenges through its unique combination of long-term data, cross-site comparisons, and interdisciplinary approaches.

Future efforts will focus on integrating evolutionary processes into ecosystem models and Earth system models to better predict responses to a rapidly changing planet [24]. As one study noted, "even minor shifts in C-relevant plant traits, such as a 1% increase in rooting depth over only 4% of arable land, could offset all annual CO₂ production from fossil fuel emissions" [24], highlighting the potential significance of these eco-evolutionary dynamics for global carbon cycling.

The LTER Toolkit: Methodologies, Data Management, and Real-World Applications

The Long Term Ecological Research (LTER) Network represents a comprehensive framework for understanding ecological systems through sustained observation and experimental manipulation. Established in 1980 by the National Science Foundation, the LTER Network addresses a fundamental recognition: many critical ecological processes unfold over timeframes that exceed typical grant cycles, involving long-lived species, legacy influences, and rare events that can only be understood through decadal-scale study [3]. This network of 27 place-based research sites employs a standardized workflow that progresses systematically from long-term monitoring to large-scale experiments, creating a powerful methodology for ecological discovery across diverse ecosystems [3] [27].

The LTER approach integrates multiple scientific disciplines—including ecology, hydrology, geochemistry, and social sciences—to investigate ecological phenomena at multiple spatial and temporal scales [3] [27]. Each LTER site typically develops a research program that incorporates a conceptual model, a core set of observations, experiments designed to reveal poorly understood processes, modeling to integrate new information, and outreach efforts to engage stakeholders [27]. This structured yet flexible workflow enables both deep understanding of individual ecosystems and broad synthetic studies that reveal principles operating at regional to global scales [3].

Core Research Themes and Monitoring Framework

Foundational and Emerging Research Themes

LTER research is organized around core thematic areas that facilitate cross-site comparison and synthesis. Five core themes have been central to LTER Network science since its inception, with two additional themes emerging as the network expanded to include urban ecosystems [3]. These themes guide the systematic monitoring and experimental approaches across all LTER sites, ensuring comparable data collection while allowing site-specific adaptations.

Table 1: Core LTER Research Themes Guiding Monitoring and Experimental Design

| Theme Category | Theme Name | Key Research Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Foundational Themes | Primary Production | Plant growth as the base component of food webs; determines animal productivity |

| Population Studies | Changes in plant, animal, and microbial populations in space and time | |

| Movement of Organic Matter | Decomposition and recycling of dead plants, animals, and organisms through ecosystems | |

| Movement of Inorganic Matter | Cycling of nitrogen, phosphorus, and other mineral nutrients via decay and disturbance | |

| Disturbance Patterns | Ecosystem reorganization through fires, floods, and other periodic disturbances | |

| Emerging Themes | Land Use and Land Cover Change | Human impacts on land use and land-cover change in relation to ecosystem dynamics |

| Human-Environment Interactions | Effects of human-environmental interactions, especially in urban systems |

Quantitative Monitoring Protocols

The LTER monitoring framework employs standardized protocols across sites to ensure data comparability. Data collection for these core areas establishes baseline conditions before any experimental manipulation begins, providing essential context for interpreting experimental results [3]. The quantitative nature of this monitoring is exemplified by specific measurement protocols used across sites.

Table 2: Representative LTER Monitoring Protocols and Methodologies

| Research Area | Protocol Category | Specific Method/Measurement |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Production | Aboveground Measurement | Aboveground Net Primary Production - MCSE |

| Belowground Measurement | Belowground Net Primary Production - Biofuel Cropping System Experiment | |

| Ecosystem Processes | Greenhouse Gas Fluxes | Recirculating Chamber Method, Static Chamber Method |

| Nutrient Cycling | Long-term N Mineralization, Denitrification Enzyme Assay | |

| Soil Nutrients | Inorganic and Organic Soil Phosphorous Fractions | |

| Soil Properties | Physical Characteristics | Soil Bulk Density - Deep Cores, Particle Size Analysis |

| Chemical Properties | Soil Total Carbon and Nitrogen, Agronomic Soil Chemistry | |

| Hydrology | Water Chemistry | Hydrochemistry Protocols |

| Soil Moisture | Soil Moisture by Time Domain Reflectometry |

The Integrated LTER Workflow: From Observation to Synthesis

The LTER methodology follows a systematic progression from fundamental monitoring through experimental manipulation to data synthesis and modeling. This workflow ensures that each phase of research builds logically upon previous findings, with long-term observational data informing experimental design and experimental results refining conceptual models and future monitoring priorities.

Foundational Monitoring Phase

The workflow begins with long-term monitoring of core ecological parameters, which forms the backbone of LTER research. This monitoring establishes baseline conditions and captures slow processes and rare events that short-term studies would miss [7]. At many LTER sites, this involves sustained observations spanning more than 40 years, creating an invaluable record of ecosystem dynamics [3]. The monitoring phase is tightly coupled with rigorous data management practices, including immediate quality control and comprehensive documentation by dedicated information managers stationed at each site [7]. This careful attention to data quality at the collection stage enables future reuse and synthesis.

Experimental and Synthesis Phases

Building on patterns detected through long-term monitoring, LTER researchers develop targeted experiments to elucidate underlying mechanisms. These experiments range from small-scale manipulative studies to large-scale ecosystem experiments that alter fundamental processes [3]. The experimental phase generates new insights that feed back to refine both conceptual models and monitoring strategies. Finally, the synthesis phase integrates data from multiple sources, sites, and disciplines to generate broader ecological understanding [3] [28]. This synthesis often occurs through formally constituted working groups that bring together diverse expertise to address cross-site questions [29].

Data Management: The Backbone of LTER Science

Data Pipeline and Repository Infrastructure

The LTER Network has developed a sophisticated data management infrastructure that ensures the long-term preservation and accessibility of ecological data. This infrastructure operates as the central nervous system of the LTER workflow, connecting all phases of research from data collection through final publication and archiving. The network's commitment to data sharing is embodied in its policy of making data available online with as few restrictions as possible [7].

The LTER data infrastructure includes multiple access points tailored to different user needs. The Environmental Data Initiative (EDI) serves as the main repository for LTER data, providing curation and long-term maintenance of datasets [7]. Additionally, regional repositories such as the Biological and Chemical Oceanography Data Management Office (BCO-DMO), the Arctic Data Center, and the Dryad Digital Repository host LTER data with specific disciplinary or geographic focus [7]. This multi-tiered approach ensures both centralized access and specialized repository support.

Data Quality and FAIR Principles

LTER information managers implement rigorous quality control procedures to identify errors and inconsistencies in collected data [7]. Each dataset undergoes thorough documentation to ensure it can be incorporated into broader comparative and synthetic studies, often years after initial collection [7]. The network has been a leader in adopting FAIR data principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reproducible), with EDI maintaining a strong record of serving FAIR data to the research community [3]. This commitment to data quality and accessibility enables the unexpected reuse of data to answer new questions that emerge as ecological science evolves [7].

Table 3: LTER Data Repository Ecosystem

| Repository Type | Repository Name | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Repository | Environmental Data Initiative (EDI) | Main repository for LTER data | Curates data from multiple environmental science programs; FAIR data compliance |

| Regional/Disciplinary | Arctic Data Center | Hosts Arctic-focused LTER data | Specialized in polar research data management |

| BCO-DMO | Oceanographic LTER data | Focused on biological and chemical oceanography data | |

| Dryad Digital Repository | General purpose repository | Broad disciplinary coverage | |

| Federated Search | DataONE Federation | Cross-repository data discovery | Searches multiple repositories including LTER member node |

| Local Archives | Site-specific Catalogs | Local data before public release | Includes not-yet-public data and non-LTER data |

Experimental Design and Methodologies

Transition from Monitoring to Experimentation

The progression from observational monitoring to experimental manipulation represents a critical transition in the LTER workflow. Long-term data reveal patterns and anomalies that generate hypotheses testable through experimental approaches. For example, multi-decadal records of primary production might show unexpected declines that prompt experiments investigating potential drivers such as nutrient limitations, climate stress, or species interactions. This iterative process—where monitoring informs experimentation and experimental results refine monitoring priorities—creates a powerful feedback loop that accelerates ecological understanding.

LTER experiments are characterized by their large spatial scales and long durations, which allow researchers to address questions that cannot be answered through short-term, small-scale studies. These experiments often involve manipulations of entire ecosystem components, such as nutrient additions to watersheds, temperature manipulations in forests, or biodiversity manipulations in grasslands [30]. The scale and duration of these experiments mean they frequently reveal ecological dynamics that would be invisible in shorter-term studies, including legacy effects, tipping points, and complex interactions among multiple drivers of change.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Solutions