Implementing an Integrated Bio-logging Framework (IBF): A New Paradigm for Predictive Drug Development

This article explores the implementation of an Integrated Bio-logging Framework (IBF) to revolutionize preclinical drug development.

Implementing an Integrated Bio-logging Framework (IBF): A New Paradigm for Predictive Drug Development

Abstract

This article explores the implementation of an Integrated Bio-logging Framework (IBF) to revolutionize preclinical drug development. It details how animal-attached sensors provide high-resolution, multivariate data on physiology, behavior, and environmental interactions, offering a more predictive alternative to traditional models. We cover the foundational principles of biologging, methodological steps for integration into existing R&D workflows, strategies for troubleshooting data and analysis challenges, and the framework for validating IBF against conventional approaches. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this guide provides a roadmap for leveraging IBF to de-risk pipelines, improve translational success, and adhere to the principles of the 3Rs (Replacement, Reduction, Refinement) in animal testing.

The Foundational Shift: Why Bio-logging is the Future of Preclinical Data

Traditional preclinical models have long relied on reductionist, single-endpoint studies that often fail to capture the complex physiological responses and clinical relevance required for successful therapeutic development. This approach has contributed to significant challenges in translational research, with many promising laboratory findings failing to translate into effective clinical treatments [1] [2]. The limitations of these conventional methodologies are particularly evident in complex disease areas such as glioblastoma (GBM), where survival rates have remained stubbornly low despite decades of research, due in part to preclinical models that fail to fully recapitulate the disease's complex pathobiology [2].

The integrated bio-logging framework (IBF) represents a transformative approach that addresses these limitations through multi-dimensional data collection and analysis. Originally developed for movement ecology, the IBF's principles of multi-sensor integration, multidisciplinary collaboration, and sophisticated data analysis provide a robust methodological foundation for enhancing preclinical research across therapeutic areas [3]. This framework enables researchers to move beyond single-endpoint measurements toward a more comprehensive understanding of disease mechanisms and treatment effects in physiological contexts that more accurately model human conditions.

Limitations of Traditional Preclinical Models

Key Methodological Shortcomings

Traditional preclinical studies often employ simplified experimental designs that overlook critical aspects of clinical reality, creating significant knowledge gaps in our understanding of how therapies perform in realistic clinical settings [1]. These limitations manifest in several critical areas:

Oversimplified Disease Context: Preclinical studies tend to replicate pathological states as simply as possible, without considering the impact of complex disease states or localized pathology on therapeutic function. For example, studies of continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) typically use chemically-induced diabetes models without accounting for common comorbidities like obesity or non-alcoholic fatty liver disease that significantly alter metabolic and immune responses [1].

Inadequate Assessment of Foreign Body Response: For implantable medical devices (IMDs), the foreign body response (FBR) represents a critical factor influencing device safety and performance. Traditional preclinical models often provide limited assessment of the step-wise process of inflammation, wound healing, and potential end-stage fibrosis and scarring that can impair device integration and long-term functionality [1].

Limited Generalizability: Single-laboratory studies demonstrate significantly larger effect sizes and higher risk of bias compared to multilaboratory studies, which show smaller treatment effects and greater methodological rigor analogous to trends well-recognized in clinical research [4].

Quantitative Evidence: Single vs. Multilaboratory Studies

Table 1: Comparison of Single Laboratory vs. Multilaboratory Preclinical Studies

| Study Characteristic | Single Laboratory Studies | Multilaboratory Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Median Sample Size | Not reported | 111 animals (range: 23-384) |

| Typical Number of Centers | 1 | 4 (range: 2-6) |

| Risk of Bias | Higher | Significantly lower |

| Effect Size (Standardized Mean Difference) | Larger by 0.72 (95% CI: 0.43-1.0) | Significantly smaller |

| Generalizability Assessment | Limited | Built into study design |

| Common Model Systems | Various rodent models | Stroke, traumatic brain injury, myocardial infarction, diabetes |

The data reveal that multilaboratory studies demonstrate trends well-recognized in clinical research, including smaller treatment effects with multicentric evaluation and greater rigor in study design [4]. This approach provides a method to robustly assess interventions and the generalizability of findings between laboratories, addressing a critical limitation of traditional single-laboratory preclinical research.

The Integrated Bio-logging Framework (IBF): Principles and Implementation

The Integrated Bio-logging Framework (IBF) offers a systematic approach to overcoming the limitations of traditional preclinical models by facilitating the collection and analysis of high-frequency multivariate data [3]. This framework connects four critical areas—questions, sensors, data, and analysis—through a cycle of feedback loops linked by multidisciplinary collaboration.

Core Components of the IBF

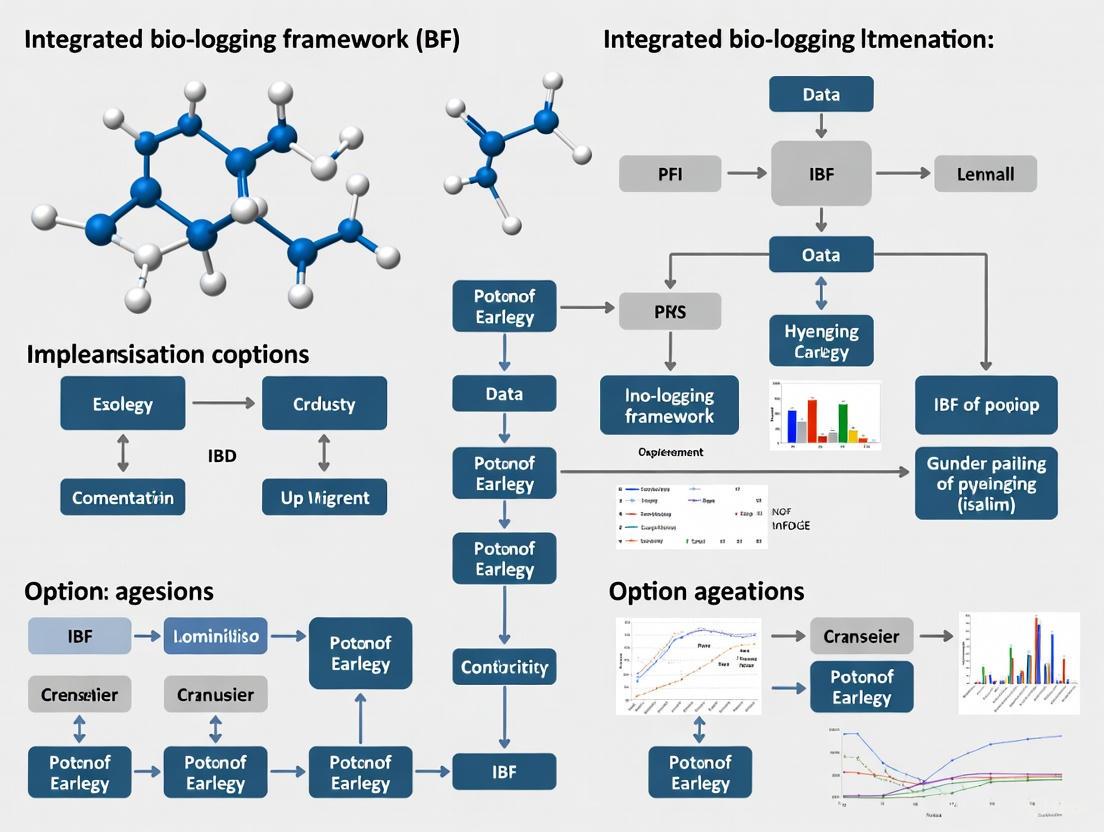

IBF Framework Diagram: Integrated approach to preclinical study design

The IBF enables researchers to address fundamental questions in movement ecology and therapeutic development through optimized sensor selection and data analysis strategies [3]. The framework emphasizes that multi-sensor approaches represent a new frontier in bio-logging, while also identifying current limitations and avenues for future development in sensor technology.

Sensor Technologies for Comprehensive Data Collection

Table 2: Bio-logging Sensor Types and Applications in Preclinical Research

| Sensor Category | Specific Sensors | Measured Parameters | Preclinical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Location Sensors | GPS, pressure sensors, acoustic telemetry, proximity sensors | Animal position, altitude/depth, social interactions | Space use assessment, interaction studies, migration patterns |

| Intrinsic Sensors | Accelerometers, magnetometers, gyroscopes, heart rate loggers, temperature sensors | Body posture, dynamic movement, orientation, physiological states | Behavioural identification, energy expenditure, 3D movement reconstruction, feeding activity, stress response |

| Environmental Sensors | Temperature loggers, microphones, video loggers, proximity sensors | Ambient conditions, soundscape, visual environment | Contextual behavior analysis, environmental preference studies, external factor impact assessment |

The combined use of multiple sensors can provide indices of internal 'state' and behavior, reveal intraspecific interactions, reconstruct fine-scale movements, and measure local environmental conditions [3]. This multi-dimensional data collection represents a significant advancement over traditional single-endpoint measurements.

Application Notes: Implementing the IBF in Specific Disease Contexts

Protocol 1: Comprehensive Assessment of Implantable Medical Devices

Background: Implantable medical devices (IMDs) represent a rapidly growing market expected to reach a global value of $153.8 billion by 2026 [1]. Traditional preclinical assessment of IMDs often focuses on simplified functional endpoints without adequate consideration of complex physiological responses, particularly the foreign body response (FBR) that can significantly impact device safety and performance.

Detailed Experimental Workflow:

IMD Assessment Workflow: Comprehensive device evaluation protocol

Key Methodological Considerations:

Animal Model Selection: Choose models that replicate clinically relevant comorbidities. For diabetes device testing, this includes models incorporating conditions like non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) that create distinct physiological contexts affecting device performance [1].

Multi-sensor Integration: Combine accelerometers for activity monitoring, temperature sensors for local inflammation assessment, and continuous physiological monitoring relevant to device function (e.g., glucose monitoring for CGMs).

Histopathological Correlation: Conduct detailed histopathology at multiple time points post-implantation to assess inflammation and fibrosis at the device-tissue interface, correlating these findings with sensor-derived functional data [1].

Foreign Body Response Monitoring: Systematically evaluate the step-wise FBR process, including initial inflammation, wound healing, and potential fibrotic encapsulation that can impair device functionality [1].

Protocol 2: Advanced Glioblastoma Therapeutic Assessment

Background: Glioblastoma (GBM) remains one of the most challenging cancers with less than 5% of patients surviving 5 years, due in part to preclinical models that fail to fully recapitulate GBM pathophysiology [2]. Traditional models have limited ability to mimic the disease's complex heterogeneity and highly invasive potential, hindering efficient translation from laboratory findings to successful clinical therapies.

Detailed Experimental Workflow:

GBM Therapeutic Assessment: Multi-stage evaluation approach

Key Methodological Considerations:

Novel Model Systems: Implement emerging animal-free approaches that show evidence of more faithfully recapitulating GBM pathobiology with high reproducibility, offering new biological insights into GBM etiology [2].

Multilaboratory Validation: Engage multiple research centers in therapeutic assessment to enhance generalizability and reduce the risk of bias, following the established principle that multilaboratory studies demonstrate significantly smaller effect sizes and greater methodological rigor compared to single laboratory studies [4].

Multi-parameter Assessment: Move beyond traditional endpoint measures like tumor volume to include functional assessments of invasion, metabolic activity, and treatment response heterogeneity using integrated sensor systems.

Data Integration: Develop advanced analytical approaches for integrating high-dimensional data from multiple sources to identify complex patterns and biomarkers of treatment response.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for IBF Implementation

| Reagent/Material Category | Specific Examples | Function in IBF Research | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bio-logging Sensors | Accelerometers, magnetometers, gyroscopes, pressure sensors, temperature loggers | Capture patterns in body posture, dynamic movement, orientation, and environmental conditions | Miniaturization requirements, power consumption, data storage capacity, sampling frequency optimization |

| Telemetry Systems | Implantable telemetry, external logging devices, data transmission systems | Enable remote monitoring of physiological parameters and device function in freely moving subjects | Transmission range, data integrity, battery life, biocompatibility for implantable systems |

| Data Analysis Platforms | Machine learning algorithms, Hidden Markov Models, multivariate statistical packages | Facilitate analysis of complex, high-frequency multivariate data to identify patterns and behavioral states | Computational requirements, algorithm validation, integration of multiple data streams |

| Specialized Animal Models | Comorbid disease models, patient-derived xenografts, genetically engineered systems | Provide pathophysiological contexts that more accurately reflect clinical conditions | Model validation, reproducibility assessment, relevance to human disease mechanisms |

| Histopathological Tools | Specialized staining techniques, digital pathology platforms, 3D reconstruction software | Enable detailed assessment of tissue responses and correlation with functional data | Standardized scoring systems, quantitative analysis methods, integration with sensor data |

Statistical Considerations and Meta-analytical Approaches

The implementation of IBF principles generates complex, high-dimensional data that requires sophisticated statistical approaches. Meta-analysis of preclinical data plays a crucial role in evaluating the consistency of findings and informing the design and conduct of future studies [5]. Unlike clinical meta-analysis, preclinical data often involve many heterogeneous studies reporting outcomes from a small number of animals, presenting unique methodological challenges.

Advanced Statistical Methods for IBF Data

Heterogeneity Estimation: Restricted maximum likelihood (REML) and Bayesian methods should be preferred over DerSimonian and Laird (DL) for estimating heterogeneity in meta-analysis, especially when there is high heterogeneity in the observed treatment effects across studies [5].

Multivariable Meta-regression: This approach explains substantially more heterogeneity than univariate meta-regression and should be preferred to investigate the relationship between treatment effects and multiple study design and characteristic variables [5].

Machine Learning Integration: Incorporate machine learning approaches for identifying behaviors from tri-axial acceleration data and Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) to infer hidden behavioral states, balancing model complexity with interpretability [3].

The implementation of the Integrated Bio-logging Framework represents a paradigm shift in preclinical research, moving beyond traditional single-endpoint models toward a more comprehensive, multidimensional approach. By adopting the principles of multi-sensor integration, multidisciplinary collaboration, and sophisticated data analysis, researchers can address fundamental limitations in current preclinical models and enhance the translational potential of their findings.

The evidence clearly demonstrates that multilaboratory studies incorporating IBF principles demonstrate greater methodological rigor, smaller effect sizes that may more accurately reflect clinical reality, and enhanced generalizability compared to traditional single-laboratory approaches [4]. Furthermore, the integration of multiple data streams through advanced sensor technologies enables researchers to capture the complex physiological responses and environmental interactions that significantly impact therapeutic safety and efficacy in clinical settings.

As preclinical research continues to evolve, the adoption of IBF principles and methodologies will be essential for developing more accurate models of human disease, improving the efficiency of therapeutic development, and ultimately enhancing the translation of laboratory findings to clinical applications across a wide range of therapeutic areas, from implantable medical devices to complex neurological conditions like glioblastoma.

The Integrated Bio-logging Framework (IBF) is a structured methodology designed to optimize the use of animal-attached electronic devices (bio-loggers) for ecological research, particularly in movement ecology. It addresses the critical challenge of matching the most appropriate sensors and analytical techniques to specific biological questions, a process that has become increasingly complex with the proliferation of bio-logging technologies [3]. The IBF synthesizes the decision-making process into a cohesive system that emphasizes multi-disciplinary collaboration to catalyze the opportunities offered by current and future bio-logging technology, with the goal of developing a vastly improved mechanistic understanding of animal movements and their roles in ecological processes [3].

The Core Framework and Its Components

The IBF connects four critical areas for optimal study design—Questions, Sensors, Data, and Analysis—within a cycle of feedback loops. This structure allows researchers to adopt either a question/hypothesis-driven (deductive) or a data-driven (inductive) approach to their study design, providing flexibility to accommodate different research paradigms [3]. The framework is built on the premise that bio-logging is now so multifaceted that establishing multi-disciplinary collaborations is essential for its successful implementation. For instance, physicists and engineers can advise on sensor capabilities and limitations, while mathematical ecologists and statisticians can aid in framing study design and modeling requirements [3].

Diagram: Integrated Bio-logging Framework (IBF) Structure

From Biological Questions to Sensor Selection

The first critical transition in the IBF involves matching appropriate bio-logging sensors to specific biological questions. This process should be guided by the fundamental questions posed by movement ecology, which include understanding why animals move (motivation), how they move (movement mechanisms), what the movement outcomes are, and when and where they move [3]. The IBF provides a structured approach to selecting sensors that can best address these questions, moving beyond simple location tracking to multi-sensor approaches that can reveal internal states, intraspecific interactions, and fine-scale movements [3].

Table 1: Bio-logging Sensor Types and Their Applications

| Sensor Type | Examples | Description | Relevant Biological Questions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Location | Animal-borne radar, pressure sensors, passive acoustic telemetry, proximity sensors | Determines animal position based on receiver location or other reference points | Space use; animal interactions; habitat selection |

| Intrinsic | Accelerometer, magnetometer, gyroscope, heart rate loggers, stomach temperature loggers | Measures patterns in body posture, dynamic movement, body rotation, orientation, and physiological metrics | Behavioural identification; internal state; 3D movement reconstruction; energy expenditure; biomechanics; feeding activity |

| Environmental | Temperature sensors, microphones, proximity sensors, video loggers | Records external environmental conditions and context | Space use in relation to environmental variables; energy expenditure; external factors influencing behaviour; interactions with environment |

Diagram: Question-to-Sensor Selection Workflow

Data Management and Analytical Protocols

The IBF emphasizes the importance of efficient data exploration, advanced multi-dimensional visualization methods, and appropriate archiving and sharing approaches to tackle the big data issues presented by bio-logging [3]. This is particularly critical given the high-frequency, multivariate data generated by modern bio-logging sensors, which greatly expand the fundamentally limited and coarse data that could be collected using location-only technology such as GPS [3]. The framework addresses the challenges of matching peculiarities of specific sensor data to statistical models, highlighting the need for advances in theoretical and mathematical foundations of movement ecology to properly analyse bio-logging data [3].

Multi-Sensor Data Integration Protocol

Objective: To reconstruct fine-scale 3D animal movements using dead-reckoning procedures that combine multiple sensor data streams.

Materials and Equipment:

- Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) containing accelerometer, magnetometer, and gyroscope

- Depth or pressure sensor for aquatic/terrestrial altitude measurement

- GPS or Argos location sensor for periodic ground-truthing

- Data storage or transmission unit

- Animal attachment harness appropriate to species

Procedure:

- Sensor Calibration: Calibrate all sensors prior to deployment according to manufacturer specifications.

- Synchronization: Ensure all sensors are synchronized to a common time source with sufficient resolution for the behavior of interest.

- Data Collection:

- Collect tri-axial acceleration data at frequency sufficient to capture behaviors of interest (typically >10Hz)

- Collect tri-axial magnetometer data at same frequency as accelerometer

- Collect depth/pressure data at frequency appropriate for vertical movement patterns

- Collect periodic GPS fixes for position reference

- Data Processing:

- Calculate speed using speed-dependent dynamic body acceleration (DBA) for terrestrial animals [3]

- Determine animal heading from magnetometer data, corrected for local magnetic declination

- Integrate change in altitude/depth from pressure data

- Path Reconstruction:

- Calculate successive movement vectors using speed, heading, and change in altitude/depth

- Apply periodic position fixes from GPS to correct for cumulative error in dead-reckoning

- Validation: Compare reconstructed path with known movements or direct observations where possible

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The successful implementation of the IBF requires access to appropriate technological tools and analytical resources. The following table details key research reagent solutions essential for conducting bio-logging research within this framework.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Bio-logging Research

| Category | Specific Tools/Techniques | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Positioning Sensors | GPS, Argos, Geolocators, Acoustic telemetry arrays | Determining animal location and large-scale movement patterns |

| Movement & Posture Sensors | Accelerometers, Magnetometers, Gyroscopes, Gyrometers | Quantifying patterns in body posture, dynamic movement, body rotation, and orientation; dead-reckoning path reconstruction |

| Physiological Sensors | Heart rate loggers, Stomach temperature loggers, Neurological sensors, Speed paddles | Measuring internal state, energy expenditure, feeding activity, and specific behaviors |

| Environmental Sensors | Temperature sensors, Salinity sensors, Microphones, Video loggers | Recording external environmental conditions and context of animal behavior |

| Analytical Frameworks | State-space models, Hidden Markov Models (HMMs), Machine learning classifiers, Kalman filters | Inferring hidden behavioral states, identifying behaviors from sensor data, and dealing with measurement error and uncertainty |

| Data Management Tools | Movebank, Custom databases, Visualization platforms | Storing, exploring, and sharing complex bio-logging datasets |

Multi-Disciplinary Collaboration Framework

The IBF places multi-disciplinary collaboration at the center of successful bio-logging research implementation. This recognizes that the complexity of modern bio-logging requires expertise from multiple domains [3]. The framework formalizes these collaborations at different stages of the research process, from study inception through data analysis and interpretation.

Diagram: Multi-Disciplinary Collaboration Network

Implementation Pathways and Case Examples

The IBF provides structured pathways for implementation, accommodating both hypothesis-driven and data-driven approaches to research design. These pathways illustrate how researchers can navigate the framework based on their specific research goals and available resources.

Question-Driven Implementation Pathway

Protocol for Hypothesis-Driven Bio-logging Study

Objective: To implement the IBF using a deductive, question-driven approach that begins with a specific biological hypothesis.

Procedure:

- Formulate Precise Biological Question: Start with a specific hypothesis based on ecological theory or previous observations.

- Sensor Selection: Identify the sensors and sensor combinations most appropriate for addressing the biological question, considering trade-offs between data resolution, device size, power requirements, and cost.

- Study Design: Determine sampling frequencies, deployment durations, and sample sizes based on statistical power considerations and technological constraints.

- Pilot Deployment: Conduct small-scale pilot studies to validate sensor performance and experimental setup.

- Full-Scale Data Collection: Implement the full data collection protocol with appropriate controls and replication.

- Data Exploration: Use visualization techniques to identify patterns, outliers, and data quality issues.

- Analytical Model Selection: Match data characteristics to appropriate analytical frameworks (e.g., HMMs for discrete behavioral states, random walks for movement patterns).

- Interpretation and Refinement: Interpret results in biological context and refine questions for future research cycles.

Data-Driven Implementation Pathway

Protocol for Exploratory Bio-logging Analysis

Objective: To implement the IBF using an inductive, data-driven approach that begins with available datasets and seeks to identify novel patterns or relationships.

Procedure:

- Data Inventory: Compile and document available bio-logging datasets, including metadata on sensor specifications and deployment conditions.

- Data Quality Assessment: Evaluate data completeness, sensor accuracy, and potential artifacts or errors.

- Exploratory Visualization: Apply multi-dimensional visualization techniques to identify patterns, clusters, or anomalies in the data.

- Pattern Identification: Use statistical and machine learning approaches to detect significant patterns or relationships within the data.

- Biological Interpretation: Interpret identified patterns in the context of ecological theory and animal biology.

- Hypothesis Generation: Formulate specific, testable hypotheses based on the patterns observed.

- Targeted Validation: Design focused studies or analyses to validate the newly generated hypotheses.

- Model Refinement: Refine analytical models and visualization approaches based on validation results.

Future Directions and Framework Evolution

The IBF is designed to accommodate ongoing technological and analytical developments in bio-logging science. Multi-sensor approaches represent a new frontier in bio-logging, with ongoing development needed in sensor technology, particularly in reducing device size and power requirements while maintaining functionality [3]. Similarly, continued advances in data exploration, multi-dimensional visualization methods, and statistical models are needed to fully leverage the rich set of high-frequency multivariate data generated by modern bio-logging platforms [3]. The establishment of multi-disciplinary collaborations remains essential for catalyzing the opportunities offered by current and future bio-logging technology, with the IBF providing a structured framework to facilitate these collaborations and guide their productive application to fundamental questions in movement ecology.

The Integrated Bio-logging Framework (IBF) represents a paradigm shift in movement ecology and preclinical research, addressing the critical challenge of matching appropriate sensors and sensor combinations to specific biological questions [6]. This framework facilitates a cyclical process of feedback between four key areas: biological questions, sensor selection, data management, and analytical techniques, all linked through multidisciplinary collaboration [6]. The emergence of multisensor approaches marks a new frontier in bio-logging, enabling researchers to move beyond the limitations of single-sensor methodologies and gain a more comprehensive understanding of animal physiology, behavior, and environmental interactions [6]. This approach is revolutionizing both wildlife ecology and preclinical research by providing continuous, high-resolution data streams that capture subtle biological patterns previously undetectable through conventional observation or testing methods [7] [6].

Hardware Solutions: Multisensor Biologging Collars and Monitoring Systems

Integrated Multisensor Collar (IMSC) for Wildlife Research

Field Performance Metrics of IMSC

| Parameter | Performance Metric | Biological Application |

|---|---|---|

| Collar Recovery Rate | 94% success | Long-term field studies; high-value data retrieval |

| Data Recording Success | 75% cumulative rate | Reliable continuous data collection |

| Maximum Logging Duration | 421 days | Long-term ecological studies; seasonal behavior patterns |

| Behavioral Classification Accuracy | 90% overall accuracy (IMSC data) | Precise ethological studies; automated behavior recognition |

| Magnetic Heading Accuracy | Median deviation of 1.7° (lab), 0° (field) | Precise dead-reckoning path reconstruction; movement ecology |

Recent technological advances have yielded robust hardware solutions for multisensor data collection in free-ranging animals. The Integrated Multisensor Collar (IMSC) represents one such innovation, custom-designed for terrestrial mammals and extensively field-tested on 71 free-ranging wild boar (Sus scrofa) over two years [8] [9]. This system integrates multiple sensing technologies into a single platform, including GPS for positional fixes, tri-axial accelerometers for dynamic movement, and tri-axial magnetometers for orientation data, all synchronized to provide comprehensive behavioral and spatial information [8] [9]. The durability and capacity of these collars have exceeded expectations, with a 94% collar recovery rate and maximum logging duration of 421 days, demonstrating their suitability for long-term ecological studies [8] [9].

Complementing wildlife applications, multisensor home cage monitoring systems have emerged as transformative tools for preclinical research, addressing the reproducibility crisis that plagues an estimated 50-90% of published findings [7]. These systems integrate capacitive sensing, video analytics, RFID tracking, and thermal imaging to provide continuous, non-intrusive monitoring of animals in their home environments [7]. By leveraging complementary data streams and cross-validation mechanisms, multisensor platforms enhance data quality and reliability while reducing environmental artifacts and stress-induced behaviors that commonly compromise conventional testing approaches [7].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials for Multisensor Biologging

Essential Research Materials for Multisensor Biologging

| Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Sensor Systems | Tri-axial accelerometers (LSM303DLHC, LSM9DS1); tri-axial magnetometers; GPS modules (Vertex Plus); pressure sensors | Capture movement, orientation, position, and depth data |

| Data Management | Wildbyte Technologies Daily Diary data loggers; 32 GB MicroSD cards; SAFT 3.6V lithium batteries (LS17500CNR) | Data storage, power supply, and continuous recording |

| Deployment Hardware | Custom-designed polyurethane housings; PVC-U cylindrical tube housings; plastic collar belts; integrated drop-off mechanisms; VHF beacons | Animal attachment, equipment protection, and tag recovery |

| Calibration Tools | Hard- and soft-iron magnetometer correction algorithms; bench calibration fixtures | Sensor calibration and data accuracy validation |

| Software Platforms | MATLAB tools (CATS-Methods-Materials); Animal Tag Tools Project; Ethographer; Igor-based analysis packages | Data processing, visualization, and analysis |

Experimental Protocols for Multisensor Biologging

Protocol 1: IMSC Deployment and Data Collection in Free-Ranging Terrestrial Mammals

Objective: To deploy integrated multisensor collars on free-ranging terrestrial mammals for the continuous monitoring of physiology, behavior, and environmental interactions within an Integrated Bio-logging Framework.

Materials Preparation:

- Integrated Multisensor Collars (IMSCs) with integrated drop-off mechanisms and VHF beacons

- Sedation equipment appropriate for target species (e.g., dart tranquilizer methods for wild boar)

- Calibration equipment for pre-deployment sensor validation

- GPS-enabled tracking devices for collar recovery

Procedure:

- Pre-deployment Sensor Calibration: Conduct laboratory bench calibrations for all sensors, particularly focusing on magnetometer calibrations for hard- and soft-iron corrections to ensure accurate heading data [9] [10].

- Animal Capture and Handling: Capture target animals using species-appropriate methods (corral traps for wild boar); sedate using protocols approved by relevant ethics committees [9].

- Collar Deployment: Fit IMSCs ensuring proper orientation of sensors relative to major body axes; record deployment metadata including animal biometrics, collar orientation, and deployment timestamp [8] [9].

- Field Monitoring: Monitor animal movements via VHF signals as needed; record environmental conditions and potential confounding factors throughout deployment period.

- Collar Recovery: Activate drop-off mechanisms at pre-programmed intervals or locate via VHF beacons; retrieve collars for data download.

- Data Download and Verification: Download stored sensor data; verify data integrity and completeness before proceeding to analysis.

Validation Methods:

- Compare recovered collar data with field observations

- Validate sensor readings against known values or conditions where possible

- Calculate performance metrics including data recording success rate and logging duration [8]

Protocol 2: Multisensor Home Cage Monitoring in Preclinical Research

Objective: To implement multisensor home cage monitoring systems for continuous, non-intrusive assessment of animal behavior and physiology in preclinical research settings.

Materials Preparation:

- Multisensor home cage monitoring system (e.g., capacitive sensing arrays, video tracking, RFID)

- Standardized individually ventilated cages (IVCs) compatible with sensor systems

- Data acquisition and storage infrastructure capable of handling large datasets

- Environmental control systems to maintain standardized conditions

Procedure:

- System Calibration: Calibrate all sensors according to manufacturer specifications; validate tracking accuracy using known objects or animals prior to study initiation [7].

- Experimental Setup: Place capacitive sensors non-intrusively on cage rack under home cages; position infrared high-definition cameras for side-view video acquisition; install RFID baseplates with antenna matrix [7].

- Animal Acclimation: Acclimate animals to monitored home cages for a minimum of 48 hours prior to data collection to reduce stress-induced artifacts.

- Continuous Data Collection: Initiate simultaneous data collection from all sensors at appropriate sampling frequencies (e.g., capacitive sensors at 250 ms intervals) [7].

- Environmental Monitoring: Record and maintain standardized environmental conditions (light-dark cycles, temperature, humidity) throughout study duration.

- Data Integration: Synchronize timestamps across all sensor data streams to enable multimodal data fusion and cross-validation.

Validation Methods:

- Correlate baseplate-derived ambulatory activity with manual tracking and side-view whole-cage video pixel movement [7]

- Implement cross-validation between sensor modalities to confirm behavioral classifications

- Compare system outputs with manual behavioral scoring by trained observers

Protocol 3: Behavioral Classification Using Machine Learning from Multisensor Data

Objective: To develop and validate a machine learning classifier for identifying specific behaviors from multisensor accelerometer and magnetometer data.

Materials Preparation:

- Multisensor data (accelerometer, magnetometer, GPS) from animal-borne tags or monitoring systems

- Ground truth behavioral observations (video recordings or direct observations)

- Computing infrastructure with appropriate machine learning libraries (MATLAB, Python, R)

- Data partitioning framework for training, validation, and testing datasets

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Extract raw accelerometer and magnetometer data at appropriate sampling frequency (e.g., 10 Hz for wild boar) [8] [9].

- Feature Engineering: Calculate relevant features from raw sensor data including dynamic body acceleration, pitch, roll, heading, and spectral components across defined time windows.

- Ground Truth Labeling: Synchronize sensor data with ground truth behavioral observations from video or direct observation; assign behavioral labels to corresponding sensor data segments.

- Classifier Training: Partition labeled data into training and validation sets; train machine learning classifier (e.g., k-nearest neighbor, random forest, or support vector machine) using selected features.

- Classifier Validation: Test trained classifier on withheld validation data; calculate overall accuracy and class-specific performance metrics.

- Cross-Platform Validation: Validate classifier performance across different collar designs or sensor configurations to assess robustness [8].

Validation Methods:

- Calculate overall classification accuracy and create confusion matrices for behavioral classes

- Compare classifier performance across different sensor configurations

- Validate against ground truth observations collected in controlled settings [8] [9]

Data Processing and Analysis Workflows

The transformation of raw multisensor data into biologically meaningful metrics requires sophisticated processing workflows. The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive data processing pipeline from raw sensor data to ecological insights:

Multisensor Data Processing and Analysis Workflow

Data Integration and Sensor Calibration

The initial stage in multisensor data processing involves importing and synchronizing diverse data streams from various sensors into a common format to facilitate downstream analysis [10]. This is particularly crucial as different tag manufacturers use proprietary data formats and compression techniques to maximize storage capacity and minimize download time [10]. Following data import, comprehensive sensor calibration is essential to ensure data accuracy. For magnetometers, this involves both hard-iron and soft-iron corrections to account for fixed magnetic biases and field distortions caused by the tag structure or nearby ferromagnetic materials [9] [10]. Additionally, accelerometer-based tilt-compensation corrections are necessary for deriving accurate magnetic compass headings from raw magnetometer data [9].

Orientation, Motion, and Behavioral Classification

Once sensor data is calibrated, the processing pipeline advances to calculating animal orientation (pitch, roll, and heading), motion metrics (speed, specific acceleration), and positional information (depth, spatial coordinates) [10]. The integration of GPS technology with accelerometer and magnetometer data significantly enhances the accuracy of dead-reckoning path reconstruction by mitigating drift and heading errors that accumulate over time [9]. The final analytical stage applies machine learning techniques to classify behaviors from the processed sensor data. As demonstrated in wild boar studies, this approach can identify six distinct behavioral classes with 85-90% accuracy, validated across individuals equipped with different collar designs [8] [9]. The magnetometer data significantly enhances classification performance by providing additional orientation information beyond what can be derived from accelerometers alone [9].

Implementation Framework and Best Practices

Integrated Bio-logging Framework Decision Pathway

The effective implementation of multisensor biologging requires careful planning within the context of an Integrated Bio-logging Framework. The following diagram illustrates the decision pathway from biological questions through sensor selection to analytical outcomes:

Integrated Bio-logging Framework Decision Pathway

Performance Metrics and Validation Standards

Performance Metrics of Multisensor Biologging Systems

| System Component | Performance Metric | Validation Method | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Integrated Multisensor Collar | Recovery Rate | Field deployments with VHF tracking | 94% success [8] |

| Data Recording System | Success Rate | Cumulative data integrity checks | 75% across all deployments [8] |

| Behavioral Classifier | Classification Accuracy | Comparison with ground truth video | 85-90% for 6 behavioral classes [8] |

| Magnetic Compass | Heading Accuracy | Laboratory and field calibration | Median deviation 1.7° (lab), 0° (field) [8] |

| Home Cage Monitoring | Tracking Accuracy | Correlation with manual scoring | Over 99% in markerless multi-animal tracking [7] |

| Dead-Reckoning Path | Positional Accuracy | Comparison with GPS fixes | Improved drift correction with sensor fusion [9] |

Best Practices for Multisensor Biologging Implementation

Successful implementation of multisensor biologging requires adherence to several key principles. First, researchers should adopt a question-driven approach to sensor selection, carefully matching sensor combinations to specific biological questions rather than deploying maximum sensor capacity indiscriminately [6]. Second, multidisciplinary collaboration is essential throughout the process, involving expertise from ecology, engineering, computer science, and statistics to optimize tag design, data processing, and analytical interpretation [6]. Third, researchers must implement robust data management strategies to handle the large, complex datasets generated by multisensor systems, including efficient data exploration techniques, advanced multi-dimensional visualization methods, and appropriate archiving and sharing approaches [6].

For preclinical applications, multisensor home cage monitoring systems should prioritize non-intrusive data collection that minimizes disruption to natural behavioral patterns while maximizing data quality through complementary sensor modalities [7]. Validation against established behavioral scoring methods is essential, and researchers should leverage the cross-validation capabilities of multisensor systems to enhance data reliability through technological complementarity [7]. Finally, standardization of data formats and processing pipelines across research groups will facilitate comparison between studies and species, addressing a critical challenge in the biologging field [8] [6].

The multisensor advantage in capturing integrated data on physiology, behavior, and environment represents a transformative approach in both movement ecology and preclinical research. Through the implementation of Integrated Bio-logging Frameworks, researchers can leverage complementary sensor technologies to overcome the limitations of single-sensor methodologies, generating rich, high-dimensional datasets that provide unprecedented insights into animal biology. The continued refinement of multisensor collars, home cage monitoring systems, and analytical techniques will further enhance our ability to study the unobservable, advancing both fundamental ecological knowledge and applied biomedical research. As the field progresses, emphasis on standardized protocols, multidisciplinary collaboration, and sophisticated data management will be crucial for realizing the full potential of multisensor approaches in addressing complex biological questions.

The paradigm-changing opportunities of bio-logging sensors for ecological research, particularly in movement ecology, are vast [3]. These miniature animal-borne devices log and/or relay data about an animal's movements, behaviour, physiology, and environment, enabling researchers to observe the unobservable [11]. However, the crucial challenge lies in optimally matching the most appropriate sensors and sensor combinations to specific biological questions while effectively analyzing the complex, high-dimensional data generated [3]. The Integrated Bio-logging Framework (IBF) addresses this challenge by providing a structured approach to connect research questions with sensor capabilities through a cycle of feedback loops [3].

The IBF connects four critical areas for optimal study design—questions, sensors, data, and analysis—linked by multi-disciplinary collaboration [3]. This framework guides researchers in developing their study design, typically starting with the biological question but accommodating both question-driven and data-driven approaches [3]. As bio-logging has become increasingly multifaceted, establishing multi-disciplinary collaborations has become essential, with physicists and engineers advising on sensor types and limitations, while mathematical ecologists and statisticians aid in framing study design and modeling requirements [3].

Sensor Selection Framework and Question Alignment

Matching Sensors to Core Research Questions

Selecting appropriate bio-logging sensors should be fundamentally guided by the biological questions being asked [3]. The IBF provides a structured approach to align sensor capabilities with key movement ecology questions posed by Nathan et al. (2008), ensuring that research design drives technological implementation rather than vice versa [3].

Table: Alignment of Bio-logging Sensor Types with Research Questions

| Research Question Category | Primary Sensor Types | Specific Applications | Data Outputs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Where is the animal going? | GPS, ARGOS, Geolocators, Acoustic Tracking Arrays, Pressure Sensors (altitude/depth) [3] | Space use; Migration patterns; Habitat selection [3] | Location coordinates; Altitude/Depth measurements; Movement trajectories [3] |

| What is the animal doing? | Accelerometers, Magnetometers, Gyroscopes, Microphones, Hall Sensors [3] | Behavioural identification; Feeding activity; Social interactions; Vocalizations [3] | Body posture; Dynamic movement; Specific behaviours; Vocalization counts [3] |

| What is the animal's internal state? | Heart Rate Loggers, Stomach Temperature Loggers, Neurological Sensors, Speed Paddles/Pitot Tubes [3] | Energy expenditure; Physiological stress; Digestive processes; Metabolic rate [3] | Heart rate variability; Gastric temperature; Neural activity; Speed through medium [3] |

| How does the animal interact with its environment? | Temperature Sensors, Microphones, Proximity Sensors, Video Loggers, Salinity Sensors [3] | Environmental preferences; Social dynamics; Response to environmental variables [3] | Ambient temperature; Soundscapes; Association patterns; Visual context [3] |

Multi-sensor approaches represent a new frontier in bio-logging, with the combined use of multiple sensors providing indices of internal state and behaviour, revealing intraspecific interactions, reconstructing fine-scale movements, and measuring local environmental conditions [3]. For example, combining geolocator and accelerometer tags has enabled researchers to record flight behaviour of migrating swifts, while micro barometric pressure sensors have uncovered the aerial movements of migrating birds [3]. A key advantage of multi-sensor approaches is that when one sensor type fails (e.g., GPS fails under canopy cover), others can compensate through techniques like dead-reckoning, which uses speed, animal heading, and changes in altitude/depth to calculate successive movement vectors [3].

Advanced Multi-Modal Sensor Integration

The most powerful applications of bio-logging emerge from integrating multiple sensor types to create comprehensive pictures of animal lives. Inertial Measurement Units (IMUs)—particularly accelerometers, magnetometers, and pressure sensors—have revolutionized our ability to study animals as necessary electronics have gotten smaller and more affordable [10]. These animal-attached tags allow for fine-scale determination of behavior in the absence of direct observation, particularly useful in the marine realm where direct observation is often impossible [10].

Modern devices can integrate more power-hungry and sensitive instruments, such as hydrophones, cameras, and physiological sensors [10]. For instance, recent research on basking sharks has employed "a Frankenstein-style set of biologgers" including CATS animal-borne camera tags to measure feeding frequency and energetic costs, alongside acoustic proximity loggers to create social networks from detection data [12]. This multi-modal approach simultaneously tests hypotheses about both foraging efficiency and social drivers of aggregation behavior [12].

Image-based bio-logging represents a particularly promising frontier, with rapid advancements in technology—especially in the miniaturization of image sensors—changing the game for understanding marine ecosystems [13]. Small, lightweight devices can now capture a wide range of underwater visuals, including still images, video footage, and sonar readings of everything animals do, see, and encounter in their daily lives [13]. When aligned with other bio-logging data streams like depth, movement, and location, these image data sources provide unprecedented windows into animal behavior and environmental interactions.

Experimental Protocols for IBF Implementation

Protocol 1: Multi-Sensor Deployment for Terrestrial Carnivores

This protocol outlines a methodology for studying fine-scale energetics and behavior of wolves using accelerometers and GPS sensors, based on research presented at the "Wolves Across Borders" conference [12].

Objective: To understand wolf activity patterns, energetic expenditure, and livestock depredation behavior through high-resolution sensor data.

Materials and Equipment:

- GPS collars with integrated tri-axial accelerometers

- Data download station or remote data retrieval system

- Computer with appropriate data processing software (e.g., MATLAB, R)

- Calibration equipment for sensor validation

Procedure:

- Sensor Configuration: Program accelerometers to sample at minimum 20 Hz frequency to capture detailed movement signatures. Set GPS to record locations at 5-minute intervals or more frequently during focused studies.

- Deployment: Fit collars on target animals following ethical guidelines and weight restrictions (<5% of body mass). Record individual metadata including sex, weight, and age class.

- Data Collection: Allow for continuous data collection over deployment period (typically 3-12 months depending on battery life).

- Data Retrieval: Use remote download when possible or recapture animals for collar retrieval.

- Acceleration Data Processing:

- Convert raw acceleration voltages to biological metrics using calibration parameters

- Calculate overall dynamic body acceleration (ODBA) as proxy for energy expenditure

- Use machine learning classifiers (e.g., random forests) to identify behaviors from acceleration signatures

- Validate behavior classifications with field observations where possible

- Data Integration: Combine classified behaviors with GPS location data to create movement path annotations.

- Analysis: Correlate behavioral states with landscape features, time of day, and livestock presence to identify depredation risk factors.

Applications: This approach enables researchers to move beyond simple location tracking to understand behavioral states and their environmental correlates, providing crucial information for human-wildlife conflict mitigation [12].

Protocol 2: Marine Megafauna Tracking with Camera Tags

This protocol details the deployment of multi-sensor packages on marine megafauna, specifically adapted from basking shark research in Irish waters [12].

Objective: To determine drivers of basking shark aggregations by testing foraging and social hypotheses using integrated sensor packages.

Materials and Equipment:

- CATS (Customized Animal Tracking Solutions) camera tags or similar multi-sensor packages

- Suction cup attachment system or other appropriate mounting

- Boat-based echosounder for prey field mapping

- Acoustic proximity loggers for social networks

- Drones for morphological measurements

Procedure:

- Tag Preparation:

- Configure sensors including video, accelerometers, magnetometers, temperature, and depth sensors

- Test all sensor functions and memory capacity

- Calibrate sensors according to manufacturer specifications

- Animal Encounter:

- Identify target animals in aggregation hotspots

- Approach slowly to minimize disturbance

- Deploy tags using pole attachment system while animal is at surface

- Complementary Data Collection:

- Conduct boat-based echosounder transects to quantify prey density around tagged animals

- Use drones to obtain morphological measurements and context imagery

- Record group composition and size through visual surveys

- Tag Monitoring:

- Track tagged animals visually or via VHF signal if available

- Note release of tags and retrieve floating units

- Data Processing:

- Download all sensor data from recovered tags

- Synchronize video with accelerometer and depth data

- Extract feeding events from video and correlate with acceleration signatures

- Analyze proximity logger data to construct social networks

- Integrate prey field measurements with feeding behavior observations

Applications: This multi-faceted approach has revealed that basking sharks in Irish waters employ both efficient filter-feeding strategies and social information transfer, explaining their seasonal aggregations in specific coastal locations [12].

IBF Workflow Visualization

The IBF workflow operates as a continuous cycle where each stage informs and refines the others, supported throughout by multi-disciplinary collaboration [3]. Research typically begins with formulating a Biological Question, which directly guides Sensor Selection based on the parameters needed to address the question [3]. The selected sensors then Implement Data Collection, generating raw data that undergoes Data Processing to convert voltages and raw measurements into biologically meaningful metrics [3]. Processed data then Informs Analysis and Interpretation, whose findings ultimately Refine the original Biological Question, completing the iterative cycle [3]. Throughout this process, Multi-disciplinary Collaboration provides essential support at every stage, with engineers and physicists advising on sensor capabilities, statisticians guiding analytical approaches, and computer scientists developing visualization tools [3].

Research Reagents and Materials

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Equipment for Bio-Logging Studies

| Category | Specific Equipment | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Sensors | GPS/ARGOS transmitters [3] | Records location coordinates | Space use, migration patterns, home range analysis [3] |

| Motion Sensors | Tri-axial accelerometers [3] [10] | Measures dynamic body acceleration | Behaviour identification, energy expenditure, dead-reckoning [3] |

| Motion Sensors | Magnetometers [3] [10] | Determines heading/orientation | 3D movement reconstruction, navigation studies [3] |

| Motion Sensors | Gyroscopes [10] | Measures rotation rates | Stabilizing orientation estimates, fine-scale kinematics [10] |

| Environmental Sensors | Pressure sensors [3] [10] | Depth/altitude measurement | Diving behavior, flight altitude, 3D positioning [3] |

| Environmental Sensors | Temperature/salinity loggers [3] | Ambient environmental conditions | Habitat selection, environmental preferences [3] |

| Audio/Visual | Animal-borne cameras [13] | Records visual context of behavior | Foraging tactics, social interactions, environmental features [13] |

| Audio/Visual | Hydrophones/microphones [10] | Acoustic environment recording | Vocalization studies, soundscape analysis [10] |

| Physiological | Heart rate loggers [3] | Measures cardiac activity | Energy expenditure, physiological stress [3] |

| Data Processing | MATLAB tools (CATS) [10] | Converts raw data to biological metrics | Sensor calibration, orientation calculation, dead-reckoning [10] |

Data Management and Analytical Considerations

Effective implementation of the IBF requires careful attention to data management and analytical challenges. The rapid growth in bio-logging has created unprecedented volumes of complex data, presenting both opportunities and challenges for researchers [14]. Taking advantage of the bio-logging revolution requires significant improvement in the theoretical and mathematical foundations of movement ecology to properly analyze the rich set of high-frequency multivariate data [3].

Data Processing and Standardization

Processing raw bio-logging data into biologically meaningful metrics requires specialized tools and approaches. For inertial sensor data, key steps include:

- Data Import and Synchronization: Raw data from various sensors must be imported and synchronized into a common format, often challenging due to proprietary formats and varying sampling rates [10].

- Sensor Calibration: Bench calibrations are essential to correct for sensor-specific errors and misalignments, particularly for accelerometers and magnetometers [10].

- Orientation Estimation: Fusion of accelerometer, magnetometer, and gyroscope data enables calculation of animal orientation (pitch, roll, and heading) [10].

- Motion and Position Estimation: Specific acceleration (body movement independent of orientation) can be derived, and techniques like dead-reckoning combine speed estimates with heading data to reconstruct fine-scale movements between GPS fixes [10].

Establishing standardization frameworks for bio-logging data is critical for advancing ecological research and conservation [14]. Standardized vocabularies, data transfer protocols, and aggregation methods enable data integration across studies and species, facilitating broader ecological insights [14].

Emerging Analytical Approaches

Artificial intelligence and computer vision tools are transforming bio-logging data analysis, though they remain underutilized in marine science [13]. These approaches offer particular promise for:

- Automated Image Analysis: AI can dramatically improve and speed up analysis of underwater imagery collected from animal-borne cameras [13].

- Behavior Classification: Machine learning algorithms can identify behaviors from complex accelerometer data signatures [3].

- Sensor Integration: Developing lightweight models that could process images directly on-board the device while the animal is still roaming free in the wild [13].

Future advancements in bio-logging will depend on collaborative research communities at the intersection of ecology and AI, sharing data, tools, and knowledge across disciplines to accelerate discovery and drive more innovative science [13].

From Theory to Practice: A Step-by-Step Guide to IBF Implementation

The implementation of an Integrated Bio-logging Framework (IBF) requires a systematic approach to selecting sensing devices that are precisely matched to specific biological questions. This selection is critical because the capabilities of a sensor directly determine the quality, type, and reliability of data that can be acquired, which in turn influences the validity of subsequent scientific conclusions and conservation decisions. A well-defined sensor selection matrix ensures that researchers can navigate the complex trade-offs between technological specifications, biological relevance, and practical constraints. This document provides detailed application notes and protocols for aligning sensor capabilities with research objectives within an IBF context, incorporating recent methodological advances and standardized practices endorsed by the International Bio-Logging Society [15].

The foundational step in this process involves understanding the nature of the data to be collected, which directly informs sensor requirements. Biological data can be classified by its scale of measurement—nominal, ordinal, interval, or ratio—and as either qualitative/categorical or quantitative [16]. This classification guides the selection of sensors with appropriate precision, dynamic range, and data output characteristics. Furthermore, for an IBF to be successful, the selected sensors must enable data interoperability through community-accepted standards, facilitating collaboration and data fusion across studies and institutions [17].

Sensor Selection Fundamentals

Key Considerations for Sensor Assessment

Selecting a sensor for use within a bio-logging framework or clinical investigation requires a multi-faceted assessment. The following ten considerations provide a systematic evaluation framework, particularly when differentiating between medical-grade and consumer-grade devices [18].

- Regulatory Compliance and Data Security: Medical-grade devices typically comply with regulations like FDA 21 CFR Part 11 and HIPAA, ensuring data integrity and privacy. Their data ingestion and visualization platforms are designed for clinical trials, including features like audit trails. Consumer-grade devices are not required to meet these standards, potentially introducing risks related to data handling and privacy [18].

- Endpoint Degree and Suitability: The choice between medical-grade and consumer-grade sensors can depend on whether study endpoints are primary/secondary (often requiring medical-grade validation) or exploratory (where consumer-grade may be suitable). Suitability is also determined by the validation status of the sensor's measurements in the specific therapeutic or biological context [18].

- Data Display and Bias Mitigation: Medical-grade applications often include functionality to blind sensor data (e.g., blood glucose, step counts) from participants and/or researchers to prevent bias in trial outcomes. Consumer-grade apps typically display this data to users by default, which can unintentionally influence behavior and study results [18].

- Technical and Operational Characteristics: Key technical factors include device size, wearability, waterproofing, battery life, and charging requirements. From an operational standpoint, medical-grade device providers often offer dedicated support services (training, user manuals, help desks) designed for clinical trials, whereas consumer-grade companies may not [18].

- Data Transparency and Algorithmic Openness: Medical-grade device companies are more likely to provide access to raw data and details about the algorithms used to derive metrics. This allows for re-analysis with updated algorithms. The algorithms and data processing methods for consumer-grade devices are often proprietary and can change without notice, jeopardizing data consistency across a long-term study [18].

Theoretical Foundations for Sensor Performance

Beyond practical considerations, theoretical frameworks provide quantitative benchmarks for sensor performance, especially in dynamic biological environments.

Observability-Guided Biomarker Discovery: Recent advances apply observability theory from systems engineering to biomarker selection. This methodology establishes a general framework for identifying optimal biomarkers from complex datasets, such as time-series transcriptomics, by determining which sensors (e.g., specific molecules) provide the most informative signals about the underlying biological system state. The method of dynamic sensor selection further extends this to maximize observability over time, even when system dynamics themselves are changing [19].

Information-Theoretic Assessment of Transient Dynamics: Biological sensors often operate far from steady states. A comprehensive theoretical framework quantifies a sensor's performance using the Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence between the probability distributions of the sensor's stochastic paths under different environmental signals. This trajectory KL divergence, calculated as an accumulated sum of observed transition events, sets an upper limit on the sensor's ability to distinguish temporal patterns in its environment [20]. This is particularly relevant for assessing a sensor's recovery capability—its ability to reset after previous exposure to a stimulus.

Sensor Selection Matrix: Matching Capabilities to Research Goals

The following matrix synthesizes key considerations to guide researchers in aligning sensor capabilities with specific biological questions and data requirements within an IBF.

Table 1: Sensor Selection Matrix for Biological Research

| Biological Question / Data Type | Critical Sensor Capabilities | Recommended Sensor Type & Data Standards | Key Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Animal Movement & Migration | GPS accuracy, sampling frequency, battery longevity, depth rating, accelerometer sensitivity. | Satellite transmitters, GPS loggers. Data standardized per IBioLS frameworks [15] [17]; use device/deployment/input-data templates. | Fix success rate, location error (m), data yield (fixes/day), deployment duration. |

| Fine-Scale Behaviour (e.g., foraging) | High-frequency accelerometry, tri-axial magnetometry, animal-borne video/audio. | Animal-borne camera tags (e.g., CATS), acoustic proximity loggers, accelerometers. Data processed into defined behaviour classifications [12]. | Sampling rate (Hz), dynamic range (g), battery life, classification accuracy. |

| Neurobiology / Neurotransmitter Dynamics | High sensitivity (μM to nM), molecular specificity, temporal resolution (real-time). | Electrochemical sensors (amperometric/potentiometric); enzymatic (GluOx) for sensitivity vs. non-enzymatic for stability [21]. | Limit of Detection (LOD), sensitivity (μA/μM·cm²), selectivity, response time. |

| Pathogen Detection (e.g., SARS-CoV-2) | High angular sensitivity, label-free detection, real-time binding kinetics. | Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) biosensors with heterostructures (e.g., CaF₂/TiO₂/Ag/BP/Graphene) [22]. | Sensitivity (°/RIU), Detection Accuracy, Figure of Merit (FOM). |

| Cellular & Molecular Biomarker Discovery | High-plexity, ability to monitor dynamic processes, compatibility with multi-omics data. | Technologies enabling time-series transcriptomics, chromosome conformation capture. Analysis via observability-guided dynamic sensor selection [19]. | Observability score, dimensionality of state space, biomarker robustness over time. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Assessing Transient Sensory Performance using Information Theory

This protocol outlines a procedure to quantify the performance of a biological sensor when it is exposed to dynamic, non-steady-state signals, based on an information-theoretic benchmark [20].

1. Research Question and Preparation

- Objective: To measure a sensor's ability to distinguish between two different time-varying ligand concentration protocols,

c^A(t)andc^B(t), and to identify anomalous effects like the "sensory withdrawal effect." - Materials:

- Sensor System: A purified multi-state ligand-receptor system (e.g., a 4-state sensor with defined bound and unbound states).

- Microfluidic Setup: A system capable of delivering precise, time-varying concentration profiles to the sensor.

- Data Acquisition System: Equipment for recording the sensor's state transitions at high temporal resolution (e.g., a patch-clamp setup, fluorescence spectrometer, or other appropriate modality).

2. Experimental Procedure

1. System Characterization: For the chosen sensor, map all possible states and the transition rates (R_ij) between them. Confirm which transitions are concentration-dependent.

2. Protocol Design:

* Design at least two distinct temporal protocols for ligand concentration. For example:

* Protocol A: A direct step-up in concentration.

* Protocol B: A high-concentration pulse followed by a reset period at low concentration, then a step-up.

3. Pathway Recording:

* Expose the sensor to Protocol A and record its stochastic state-transition trajectory, X_τ^A, over a fixed observation time τ. Repeat for a large number of trials (N > 1000) to build robust statistics.

* Repeat the process for Protocol B to obtain X_τ^B.

4. Data Processing:

* From the recorded trajectories, compute the probability distributions P^A[X_τ] and P^B[X_τ].

* Calculate the detailed probability current J_{x'x}^A(t) for transitions from state x to x' under Protocol A.

3. Data Analysis

1. Compute Trajectory KL Divergence: Use the following formula to calculate the sensor's performance metric [20]:

D_KL^AB(τ) = Σ∫_0^τ J_{x'x}^A(t) • ln(R_{x'x}^A(t) / R_{x'x}^B(t)) dt

where the sum is over all possible state transitions <x, x'>.

2. Interpretation: A higher D_KL^AB(τ) indicates a greater ability for the sensor (and its downstream networks) to distinguish between the two temporal patterns A and B. A "sensory withdrawal effect" is demonstrated if performance under Protocol B exceeds that of Protocol A.

Protocol: Deploying Bio-logging Tags for Behavioural Ecology

This protocol provides a generalized workflow for deploying animal-borne tags to investigate movement ecology and behaviour, incorporating community standards for data collection [15] [17] [12].

1. Research Question and Preparation

- Objective: To document fine-scale foraging behaviour and social interactions in a marine predator (e.g., basking shark).

- Materials:

- Biologgers: Multi-sensor tags (e.g., CATS camera tags, accelerometers, acoustic proximity loggers).

- Attachment Equipment: Species-specific attachment tools (e.g., poles, suction cups, bolts).

- Field Equipment: Vessel, drones for scale assessment, GoPros for sex identification.

- Data Standards Templates: Device, Deployment, and Input-Data templates from the bio-logging standardization framework [17].

2. Experimental Procedure 1. Pre-Deployment: * Complete the Device Metadata Template for each tag, detailing instrument type, serial number, sensor specifications, and calibration data. * Program the tag with the desired sampling regimen (e.g., accelerometer at 50 Hz, video on a duty cycle). 2. Deployment: * Approach the target animal and securely attach the tag using the designated method. * Record all Deployment Metadata immediately: date/time, location, animal species, estimated size/sex, attachment method, and environmental conditions. * Use auxiliary methods (drones, GoPros) to gather complementary data on the individual. 3. Data Collection: * The tag records data autonomously. For proximity loggers, data on encounters with other tagged individuals is logged. * Upon tag recovery (via release mechanism or recapture), download the raw data.

3. Data Analysis 1. Data Standardization: * Compile the raw data according to the Input-Data Template. * Use automated procedures (e.g., in R or Python) to translate the raw data and metadata into standardized data levels (e.g., Level 1: raw; Level 2: corrected; Level 3: interpolated) as per the framework [17]. 2. Behavioural Classification: * Use accelerometry and video data to train machine learning models (e.g., random forest, hidden Markov models) to classify distinct behaviours (e.g., foraging, traveling, resting). 3. Data Synthesis: * Integrate classified behaviour with GPS location, prey field data (from echo-sounders), and social proximity data to test ecological hypotheses regarding habitat use and social dynamics.

Visualizing Workflows and System Relationships

Sensor Selection Logic for an Integrated Bio-logging Framework

This diagram visualizes the decision-making workflow for selecting and integrating sensors within an IBF.

Multi-State Sensor Dynamics and the Sensory Withdrawal Effect

This diagram illustrates the state transitions of a multi-state sensor and the conceptual basis for the sensory withdrawal effect.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Featured Sensor Applications

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Glutamate Oxidase (GluOx) | Enzyme for selective catalytic oxidation of glutamate in electrochemical sensors. | Enzymatic amperometric sensing of glutamate in biofluids for pain or neurodegenerative disease monitoring [21]. |

| Transition Metal Oxides (NiO, Co₃O₄) | Active materials for non-enzymatic electrochemical sensor working electrodes. | Functionalized with CNTs or beta-cyclodextrin to enhance sensitivity and stability of glutamate detection [21]. |

| 2D Nanomaterials (Graphene, BP, MoS₂) | Enhance electron transfer and provide high surface area in sensor fabrication. | Used in heterostructure SPR biosensors (e.g., CaF₂/TiO₂/Ag/BP/Graphene) to dramatically increase sensitivity for viral detection [22]. |

| IBioLS Data Standardization Templates | Standardized digital templates for reporting device, deployment, and input data metadata. | Ensuring bio-logging data is FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) and usable across global research networks [15] [17]. |

| Controlled Vocabularies (Darwin Core, Climate & Forecast) | Community-agreed terms for describing biological and sensor-based information. | Annotating bio-logging data fields to maximize interoperability with global data systems like OBIS and GEO BON [17]. |

The paradigm-changing opportunities of bio-logging sensors for ecological research, especially movement ecology, are vast. However, researchers face significant challenges in matching appropriate sensors to biological questions and analyzing the complex, high-volume data generated. The Integrated Bio-logging Framework (IBF) was developed to optimize the use of biologging techniques by creating a cycle of feedback loops connecting biological questions, sensors, data, and analysis through multi-disciplinary collaboration [3]. This framework addresses the crucial need to manage the entire data pipeline from acquisition to reusable digital assets, ensuring that valuable data can be discovered and reused for downstream investigations. The FAIR Guiding Principles provide a foundational framework for this process, emphasizing the ability of computational systems to find, access, interoperate, and reuse data with minimal human intervention [23]. This is particularly critical in movement ecology, where bio-logging has expanded the fundamentally limited and coarse data that could previously be collected using location-only technology such as GPS [3].

Table 1.1: Core Components of the Integrated Bio-logging Framework (IBF)

| Framework Component | Description | Role in Data Pipeline |

|---|---|---|

| Biological Questions | Drives sensor selection and data collection strategies [3] | Defines data requirements and purpose |

| Sensors | Animal-attached devices collecting behavioral & environmental data [3] | Data acquisition interface |

| Data | Raw and processed digital outputs from sensors [3] | Primary research asset |

| Analysis | Methods and models to extract meaning from data [3] | Creates knowledge from data |

| Multi-disciplinary Collaboration | Links all components through diverse expertise [3] | Ensures appropriate technical and analytical execution |

The FAIR Guiding Principles for Scientific Data

The FAIR Principles were published in 2016 as guidelines to improve the Findability, Accessibility, Interoperability, and Reuse of digital assets [24]. These principles put specific emphasis on enhancing the ability of machines to automatically find and use data, in addition to supporting its reuse by individuals [24]. This machine-actionability is crucial because humans increasingly rely on computational support to deal with data as a result of the increase in volume, complexity, and creation speed of data [23]. For bio-logging researchers, applying these principles transforms data from a supplemental research output into a primary, reusable research asset.

The Four FAIR Principles Explained

Findable: The first step in (re)using data is to find them. Metadata and data should be easy to find for both humans and computers. Machine-readable metadata are essential for automatic discovery of datasets and services [23]. This requires that both metadata and data are registered or indexed in a searchable resource [23].

Accessible: Once the user finds the required data, they need to know how they can be accessed, possibly including authentication and authorization [23]. The goal is to ensure that data can be retrieved by humans and machines using standard protocols.

Interoperable: Data usually need to be integrated with other data and to interoperate with applications or workflows for analysis, storage, and processing [23]. This requires the use of formal, accessible, shared, and broadly applicable languages for knowledge representation.

Reusable: The ultimate goal of FAIR is to optimize the reuse of data. To achieve this, metadata and data should be well-described so that they can be replicated and/or combined in different settings [23]. This includes accurate licensing and provenance information.

Protocol: Implementing the FAIR Data Pipeline for Bio-logging

Stage 1: Sensor Selection and Data Acquisition Planning

Purpose: To match the most appropriate sensors and sensor combinations to specific biological questions within the IBF [3].

Materials:

- Research question defining the movement ecology study

- Catalog of available bio-logging sensors

- Power requirements assessment

- Animal ethics approval protocols

- Multi-disciplinary team (biologists, engineers, physicists)

Procedure: