Guardians of the Genome: How Advanced Technologies Are Identifying Threats to Protected Ecosystems and Securing Our Pharmaceutical Future

This article explores the transformative role of cutting-edge technology in identifying and mitigating threats to protected ecosystems.

Guardians of the Genome: How Advanced Technologies Are Identifying Threats to Protected Ecosystems and Securing Our Pharmaceutical Future

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of cutting-edge technology in identifying and mitigating threats to protected ecosystems. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it details how AI, remote sensing, and bioacoustics enable real-time monitoring of biodiversity loss, habitat degradation, and climate change impacts. The content further investigates the direct link between ecosystem health and the discovery of novel biochemical compounds, providing a methodological guide for integrating conservation technology into biomedical research and ethical sourcing strategies. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with practical applications and validation frameworks, this article serves as a critical resource for safeguarding the natural reservoirs of future medicines.

The Unseen Crisis: Quantifying Threats to Biodiversity and the Direct Impact on Biomedical Discovery

The accelerating decline of species and ecosystems represents a critical challenge for global conservation efforts. For researchers and scientists focused on developing technologies to identify threats to protected ecosystems, understanding the precise scale and drivers of this decline is paramount. Recent syntheses of global data provide unprecedented insight into the magnitude of anthropogenic impacts on biodiversity across all major organismal groups and ecosystems [1]. This application note summarizes the most current quantitative data on species and ecosystem decline, presents standardized protocols for biodiversity monitoring, and outlines essential research tools for threat identification technologies. The information presented herein is designed to support research aimed at developing innovative technological solutions for ecosystem protection and threat mitigation.

Quantitative Assessment of Global Biodiversity Decline

Wildlife Population Trends

Analysis of vertebrate population trends reveals systematic declines across global ecosystems, with varying severity by geographic region and habitat type.

Table 1: Global Wildlife Population Declines (1970-2020)

| Metric | Region/Ecosystem | Decline (%) | Time Period | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average decline across monitored populations | Global | 73 | 1970-2020 | LPI [2] |

| Regional decline | Latin America & Caribbean | 95 | 1970-2020 | LPI [2] |

| Regional decline | Africa | 76 | 1970-2020 | LPI [2] |

| Regional decline | Asia-Pacific | 60 | 1970-2020 | LPI [2] |

| Regional decline | North America | 39 | 1970-2020 | LPI [2] |

| Regional decline | Europe & Central Asia | 35 | 1970-2020 | LPI [2] |

| Ecosystem-specific decline | Freshwater populations | 85 | 1970-2020 | LPI [2] |

| Ecosystem-specific decline | Terrestrial populations | 69 | 1970-2020 | LPI [2] |

| Ecosystem-specific decline | Marine populations | 56 | 1970-2020 | LPI [2] |

Table 2: Species-Specific Population Declines

| Species | Location | Decline (%) | Time Period | Conservation Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hawksbill turtle | Milman Island, Great Barrier Reef | 57 | 1990-2018 | [2] |

| Amazon pink river dolphin | Amazon | 65 | Not specified | [2] |

| Chinook salmon | Sacramento River, California | 88 | Not specified | [2] |

Species Extinction Risk Assessment

The IUCN Red List provides comprehensive data on species extinction risk, serving as a critical barometer for global biodiversity health.

Table 3: IUCN Red List Status of Assessed Species (2025)

| Taxonomic Group | Percentage Threatened | Total Assessed Species | Key Threats |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amphibians | 41% | Not specified | Habitat loss, climate change, disease [3] |

| Reef corals | 44% | Not specified | Climate change, ocean acidification [3] |

| Cycads | 71% | Not specified | Habitat loss, collection [3] |

| Sharks & Rays | 38% | Not specified | Overfishing, bycatch [3] |

| Mammals | 26% | Not specified | Habitat loss, exploitation [3] |

| Conifers | 34% | Not specified | Habitat loss, climate change [3] |

| Birds | 11% | Not specified | Habitat loss, climate change [3] |

| Reptiles | 21% | Not specified | Habitat loss, exploitation [3] |

| All Assessed Species | 28% | >172,600 | Multiple anthropogenic pressures [3] |

Experimental Protocols for Biodiversity Threat Assessment

Protocol 1: Biodiversity Intactness Index (BII) Assessment

The BII provides a standardized metric for quantifying human impacts on ecological communities relative to undisturbed reference states [4].

Workflow Overview

Materials and Methods

- Input Data Requirements:

- Processing Steps:

- Land Use Harmonization: Integrate multiple land use datasets using consistent classification schemes aligned with LUH framework [4].

- BII Modeling: Apply linear-mixed effect models to quantify spatial BII using land use inputs and abundance models [4].

- Footprint Allocation: Attribute biodiversity loss to specific agricultural commodities using spatial allocation techniques [4].

- Spatial Synthesis: Aggregate results across biomes, countries, and production sectors for time-series analysis [4].

Protocol 2: Multi-pressure Biodiversity Impact Assessment

This protocol enables standardized assessment of how different anthropogenic pressures affect biodiversity components across spatial scales.

Workflow Overview

Materials and Methods

- Dataset Composition:

- Analytical Framework:

- Log-Response Ratio Calculation: Compute LRR for homogeneity, compositional shift, and local diversity using impacted vs. reference comparisons [5].

- Mixed Model Application: Fit models to estimate magnitude and significance of biodiversity changes [5].

- Mediating Factor Testing: Evaluate effects of biome, pressure type, organism group, and spatial scale on biodiversity responses [5].

- Pressure-Specific Analysis: Quantify differential impacts of land-use change, resource exploitation, pollution, climate change, and invasive species [5].

Research Reagent Solutions for Threat Identification Technologies

Table 4: Essential Research Tools for Ecosystem Threat Monitoring

| Tool Category | Specific Solution | Research Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Remote Sensing Platforms | MODIS Sensors | Land cover classification, change detection | 500m resolution, daily temporal frequency [4] |

| Biodiversity Databases | PREDICTS Database | Biodiversity response modeling | Standardized biodiversity records across pressures [4] |

| Land Use Datasets | HILDA+ Global Land Use | Long-term land use change analysis | 1km resolution, 1960-2019 coverage, six land use classes [4] |

| Conservation Status Data | IUCN Red List | Species extinction risk assessment | Global conservation status for >172,600 species [3] |

| Population Monitoring | Living Planet Index | Vertebrate population trend analysis | Tracks 35,000 populations of 5,495 species [2] |

| Protected Area Assessment | Species Protection Index | Conservation effectiveness monitoring | Measures habitat protection adequacy for 34,000 terrestrial vertebrates [6] |

| Spatial Analysis Tools | GIS Integration | Spatial biodiversity modeling | Enables mapping of BII and biodiversity footprints [4] |

Key Findings and Research Implications

Dominant Drivers of Biodiversity Loss

The synthesized research identifies several consistent drivers of biodiversity decline:

- Habitat loss and degradation: Primarily driven by global food production systems, representing the dominant threat to wildlife populations [2].

- Overexploitation: The second most significant driver, particularly affecting marine and freshwater ecosystems [2].

- Pollution: Has particularly strong effects on community composition shifts according to meta-analysis [5].

- Climate change: An escalating pressure with differential impacts across biomes and taxonomic groups [5].

- Invasive species: Contributes to compositional changes but shows variable effects across ecosystems [5].

Conservation Efficacy Evidence

Recent data indicates that targeted conservation interventions can effectively mitigate biodiversity decline:

- Protected area coverage has increased, with 0.7% additional land area and 1.4% additional marine area gaining protection in the past year [6].

- The global Species Protection Index for terrestrial vertebrates increased from 47.8 to 50.9 (out of 100) from 2024 to 2025 [6].

- Conservation success stories include mountain gorilla populations increasing by approximately 3% per year (2010-2016) and European bison recovering from 0 to 6,800 individuals (1970-2020) [2].

The quantitative data presented in this application note establishes a rigorous baseline for developing technologies aimed at identifying threats to protected ecosystems. The documented 73% average decline in monitored wildlife populations since 1970 [2], combined with the 28% of assessed species facing extinction threats [3], underscores the critical need for innovative monitoring solutions. The experimental protocols provide standardized methodologies for assessing biodiversity impacts, while the research reagent table offers essential tools for technology development. For researchers in this field, these data highlight the importance of creating systems capable of detecting early warning signs of ecosystem degradation, particularly given the proximity to dangerous tipping points in multiple biomes [2]. Future technology development should prioritize scalable monitoring solutions that can track the five major anthropogenic pressures (land-use change, resource exploitation, pollution, climate change, and invasive species) across organizational levels from genes to ecosystems.

Biodiversity represents the foundational biological library for biomedical science and drug discovery, comprising the genetic makeup of plants, animals, and microorganisms that has evolved over millions of years [7]. This natural chemical diversity, honed by approximately 3 billion years of evolutionary trial and error, provides an irreplaceable resource for pharmaceutical innovation [8]. Natural products have historically been the source of numerous critical medications, with the World Health Organization reporting that over 50% of modern medicines are derived from natural sources, including antibiotics from fungi and painkillers from plant compounds [7]. Similarly, 11% of the world's essential medicines originate from flowering plants [9].

The current biodiversity crisis threatens this pharmaceutical pipeline. Modern extinction rates are 100 to 1000 times higher than natural background rates [8], with approximately 1 million species now threatened with extinction [7]. This represents both an ecological catastrophe and a biomedical emergency, as evidence suggests our planet may be losing at least one important drug every two years due to biodiversity loss [8]. This document outlines protocols for documenting, preserving, and utilizing biodiversity for drug discovery within the context of technological threat identification in protected ecosystems.

Quantitative Impact Assessment: The Cost of Biodiversity Loss to Medicine

Economic and Health Implications

Table 1: Economic and Health Impact of Biodiversity Loss on Medical Resources

| Impact Category | Quantitative Measure | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Global Economic Value | US$ 235-577 billion annually from pollinator-dependent crops [7] | Pollinator decline threatens food security and nutrition |

| Drug Discovery Potential | 1 important drug lost every 2 years [8] | Direct impact on pharmaceutical pipeline |

| Existing Medical Dependence | 50% of modern medicines from natural sources [7] | Current healthcare reliance on biodiversity |

| Essential Medicines | 11% of essential medicines from flowering plants [9] | Critical medications at risk from plant extinction |

| Traditional Medicine Reach | 60% of global population uses traditional medicine [7] | Primary healthcare for majority world population |

Table 2: Key Medicinal Species Threatened by Biodiversity Loss

| Species | Medical Application | Conservation Status |

|---|---|---|

| Pacific Yew Tree (Taxus brevifolia) | Source of paclitaxel for cancer chemotherapy [9] | Near threatened, population declining [9] |

| Snowdrops (Galanthus species) | Source of galantamine for Alzheimer's disease [9] | Multiple species threatened from over-harvesting [9] |

| Sweet Wormwood (Artemisia annua) | Source of artemisinin for malaria treatment [9] | Dependent on sustainable harvesting practices |

| Horseshoe Crab | Blood used to detect impurities in medicines/vaccines [9] | Classified as vulnerable [9] |

| Cone Snails (Conus species) | Venom peptides for chronic pain treatment (ziconotide) [10] | Coral reef habitat threatened [10] |

| European Chestnut Tree | Leaves yield compound neutralizing drug-resistant staph bacteria [9] | Dependent on forest conservation |

Experimental Protocols for Biodiversity-Based Drug Discovery

Protocol 1: Ecological Survey and Ethical Collection of Medicinal Species

Purpose and Principle

This protocol provides a standardized methodology for conducting ecological surveys of medicinal species and their ethical collection for drug discovery research. The approach integrates traditional knowledge with scientific assessment to identify species with therapeutic potential while ensuring sustainable practices and equitable benefit-sharing [8] [10].

Materials and Equipment

- GPS device (minimum 5m accuracy)

- Digital camera with macro capabilities

- Sterile collection kits (scalpels, forceps, containers)

- Portable DNA sequencer (e.g., MinION)

- Environmental data loggers (temperature, humidity, soil pH)

- Ethnobotanical data recording forms (digital or printed)

- Sustainable harvest measuring tools (diameter tape, quadrats)

Procedure

Step 1: Pre-Survey Preparation

- Conduct literature review of traditional medicinal knowledge for target region [10]

- Obtain prior informed consent from local communities and relevant authorities [8]

- Establish mutually agreed terms for benefit-sharing with indigenous communities [8]

Step 2: Field Identification and Documentation

- Geotag all specimen locations with GPS coordinates

- Photograph specimens in situ (habit, bark, leaves, flowers, fruits)

- Record ecological parameters: associated species, elevation, habitat type

- Document traditional knowledge: local name, uses, preparation methods [10]

- Collect voucher specimens following institutional guidelines

Step 3: Sustainable Collection

- For plants: collect less than 10% of population or use clipping techniques that allow regrowth

- For marine organisms: follow established guidelines for coral reef and marine collection [10]

- For microorganisms: use sterile techniques to isolate from soil, water, or host organisms

- Record weight/volume of collection and estimate population size

Step 4: Processing and Preservation

- Process specimens in field laboratory within 4 hours of collection

- Divide material for: (1) genetic analysis (flash frozen in liquid nitrogen), (2) chemical extraction (lyophilized), (3) herbarium/museum voucher

- Preserve traditional knowledge recordings in secure database with appropriate access controls [8]

Step 5: Data Integration

- Upload specimen data to global databases with unique identifiers

- Cross-reference with IUCN Red List status and CITES listings

- Complete ethnobotanical records with community attribution

Protocol 2: High-Throughput Screening of Biodiversity Extracts

Purpose and Principle

This protocol describes a standardized approach for creating extract libraries from biodiversity samples and screening them against disease targets using high-throughput methods. The approach maximizes discovery potential while conserving valuable biological material through miniaturization and efficient design [8].

Materials and Equipment

- Liquid handling robotics (e.g., 96-well or 384-well format)

- Lyophilizer and cryogenic grinder

- Extraction solvents (methanol, dichloromethane, hexane, water)

- Assay plates and microplate readers

- Cell culture facilities for relevant disease models

- Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) system

- Database for chemical fingerprinting

Procedure

Step 1: Extract Library Preparation

- Grind lyophilized material to uniform particle size under cryogenic conditions

- Perform sequential extraction with solvents of increasing polarity

- Concentrate extracts under reduced pressure and lyophilize

- Reconstitute in DMSO at 10 mg/mL concentration for screening

- Store extracts at -80°C in barcoded vials with inert atmosphere

Step 2: Assay Development and Validation

- Select disease-relevant molecular targets (enzymes, receptors) or cell-based assays

- Implement positive and negative controls in each plate

- Establish Z-factor >0.5 for robust assay performance

- Determine IC50 values for known inhibitors for reference

Step 3: Primary Screening

- Dispense extracts into assay plates using liquid handling robotics

- Run screens in duplicate at single concentration (10 μg/mL)

- Include vehicle controls and reference compounds in each run

- Flag hits with >50% inhibition/activity at screening concentration

Step 4: Hit Confirmation and Selectivity

- Perform dose-response curves for confirmed hits (0.1-100 μg/mL)

- Test against counter-screens to determine selectivity

- Assess cytotoxicity in relevant cell lines (e.g., HEK293)

- Confirm activity in secondary, orthogonal assays

Step 5: Chemical Fingerprinting and Dereplication

- Analyze active extracts by LC-MS to obtain chemical fingerprints

- Compare with in-house and commercial databases to identify known compounds

- Isplicate novel chemotypes for follow-up isolation

- Prioritize extracts with unique chemical profiles for fractionation

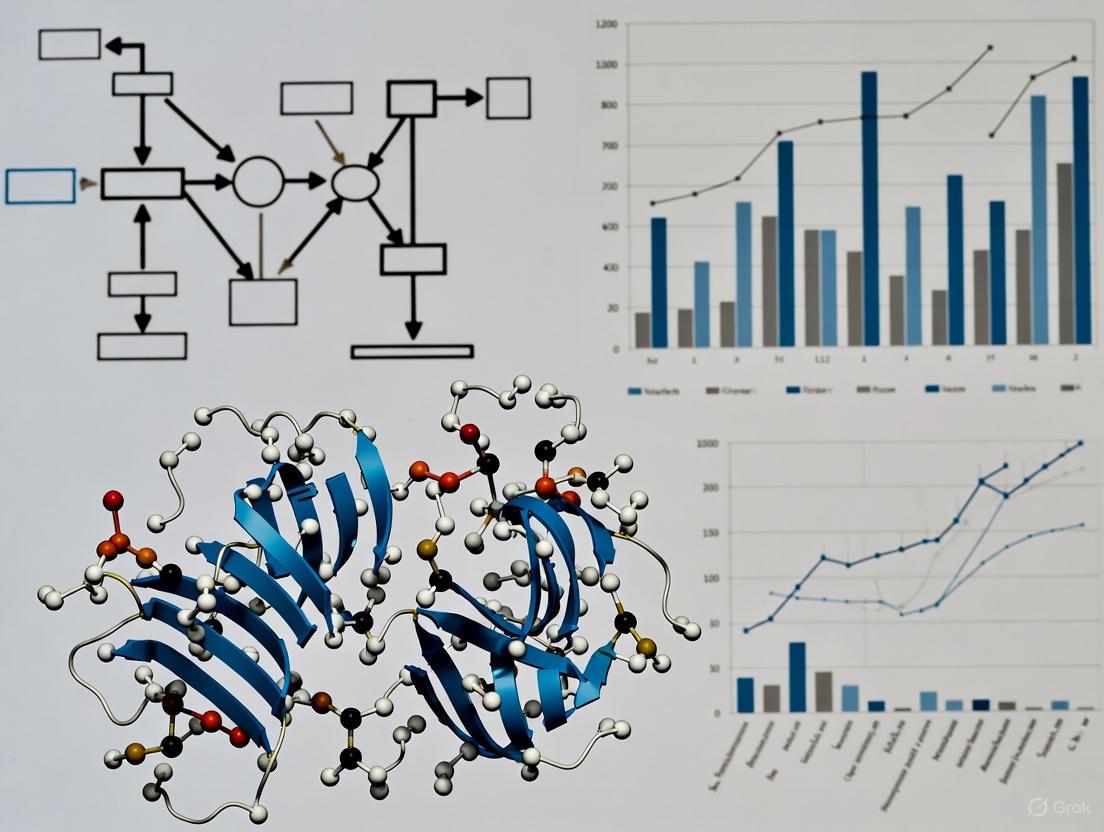

Technological Visualization: Biodiversity to Drug Discovery Pipeline

Workflow Diagram: From Ecosystem to Drug Candidate

Biodiversity Drug Discovery and Threat Monitoring Workflow

This diagram illustrates the integrated pipeline from biodiversity collection to drug candidate development, highlighting the critical role of threat monitoring technologies in identifying pressures on medicinal species and ecosystems.

Diagram: Biodiversity Loss Impact on Drug Discovery

Biodiversity Loss Impacts on Medical Discovery

This diagram maps the causal relationships between drivers of biodiversity loss and their ultimate impacts on pharmaceutical discovery and healthcare outcomes, showing how threat identification technologies can interrupt these pathways at multiple points.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Biodiversity-Based Drug Discovery

| Reagent/Solution | Application | Technical Specification |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Barcoding Kits | Species identification and authentication | Includes primers for standard barcode regions (rbcL, matK for plants; COI for animals) |

| Metabolomics Standards | Chemical fingerprinting and dereplication | Reference compounds for common natural product classes (alkaloids, terpenoids, polyketides) |

| Cell-Based Assay Systems | High-throughput screening | Engineered cell lines with reporter genes for specific disease targets |

| Traditional Knowledge Databases | Ethnobotanical leads | Structured databases with community-attributed traditional uses of species |

| LC-MS Instrumentation | Compound separation and identification | High-resolution mass spectrometry coupled with liquid chromatography |

| Cryopreservation Systems | Genetic resource conservation | Liquid nitrogen storage for tissue, DNA, and extract libraries |

| Field Collection Kits | Ethical and sustainable sampling | Sterile, sustainable harvesting tools with GPS and data logging capabilities |

Discussion: Integrating Threat Monitoring with Conservation Pharmacology

The accelerating loss of biodiversity represents both an ecological crisis and a medical emergency. With species extinction occurring at 10 to 100 times the natural baseline rate [7], and wildlife populations declining by an average of 73% over 50 years [11], the pharmaceutical pipeline faces unprecedented threats. The loss of potential medicines is particularly concerning given that many of the most effective treatments for critical conditions—including penicillin, morphine, and cancer chemotherapeutics—originate from natural sources [9].

Technologies for identifying threats to protected ecosystems play a dual role: they enable targeted conservation interventions while also guiding strategic bioprospecting efforts to document species before they are lost. The integration of real-time threat monitoring systems—including satellite imaging, acoustic monitoring, and environmental DNA sampling—can prioritize species and ecosystems for both conservation and pharmacological investigation. This approach is particularly crucial for understudied hyperdiverse taxa such as arthropods and fungi, which represent immense chemical diversity that remains largely unexplored [8].

The implementation of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework and mechanisms such as the Cali Fund provide policy and financial infrastructure to support the integration of biodiversity conservation with drug discovery [12]. By establishing equitable benefit-sharing arrangements and promoting sustainable practices, these frameworks enable a new paradigm where drug discovery actively contributes to—rather than depletes—the biological resources on which it depends.

Quantitative Synthesis of Human Impacts on Biodiversity

The following table summarizes the quantitative findings from a large-scale meta-analysis on the effects of human pressures on biodiversity, based on 3,667 independent comparisons from 2,133 published studies [5].

Table 1: Magnitude of Biodiversity Change in Response to Human Pressures

| Human Pressure | Local Diversity (Log-Response Ratio) | Compositional Shift (Log-Response Ratio) | Biotic Homogenization (Log-Response Ratio) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Impact | Not fully detailed in excerpt | 0.564 (95% CI: 0.467 to 0.661) | -0.062 (95% CI: -0.012 to -0.113) |

| Land-Use Change | Data not specified | Significant increase | No significant general trend |

| Resource Exploitation | Data not specified | Significant increase | -0.117 (95% CI: -0.197 to -0.036) |

| Pollution | Data not specified | Significant increase | -0.071 (95% CI: -0.129 to -0.012) |

| Climate Change | Data not specified | Significant increase | No significant general trend |

| Invasive Species | Data not specified | Significant increase | No significant general trend |

Key Findings: The analysis reveals a clear, significant shift in community composition across all five major human pressures, with pollution and habitat change having particularly strong effects [5]. Contrary to long-standing expectations, the meta-analysis found no evidence of systematic biotic homogenization; instead, a general trend of biotic differentiation was observed, especially at smaller spatial scales and for pressures like resource exploitation and pollution [5].

Application Notes & Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Sensor Network Deployment for Real-Time Threat Monitoring

This protocol outlines the deployment of a low-power, autonomous sensor network for continuous monitoring of habitat degradation, invasive species, and microclimatic changes [13].

Workflow Overview:

Detailed Methodology:

- Objective: To establish a distributed sensor network for detecting ecosystem threats, including invasive species, habitat degradation, and climatic shifts, in near real-time [13].

- Site Selection: Choose representative areas within the protected ecosystem, ensuring coverage of key habitats and potential threat entry points (e.g., forest edges, waterways) [13].

- Node Deployment:

- Deploy a combination of fixed and mobile sensor nodes. Fixed nodes are mounted on stakes or trees. Mobile nodes can be attached to drones, rovers, or animals for dynamic tracking [13].

- Ensure nodes are equipped with appropriate power sources, typically solar panels or long-life batteries, for extended autonomous operation [13].

- Sensor Calibration:

- Prior to deployment, calibrate all sensors against known standards.

- For bioacoustic sensors, use calibrated sound sources to standardize sensitivity across the network.

- For environmental sensors (temperature, humidity), use certified reference thermometers and hygrometers.

- Establish a schedule for recalibration every 6-12 months, or as recommended by the manufacturer, to account for sensor drift [13].

- Data Acquisition:

- Program sensors for continuous or high-frequency intermittent data collection.

- Acoustic sensors should record at a sample rate of at least 44.1 kHz to capture a wide range of animal vocalizations [14].

- Environmental sensors should log data at intervals appropriate for the measured parameter (e.g., temperature every minute, soil moisture every hour).

- Data Transmission:

- Data Processing & Analysis:

- Use AI and machine learning algorithms for automated species identification from audio (bioacoustics) and images (camera traps) [13].

- Algorithms should be trained on region-specific sound and image libraries to improve accuracy.

- Integrate data streams to create multi-layered ecosystem assessments (e.g., correlating temperature rise with changes in species activity) [13].

- Validation:

- Validate AI-generated identifications through manual review by expert ecologists for a subset of the data.

- Conduct periodic ground-truthing surveys to verify sensor data and model predictions [13].

Protocol: Climatic Niche Modeling for Invasive Species Spread

This protocol uses climatic niche modeling to predict the distribution and future spread of invasive species under climate change scenarios, using the silverleaf nightshade (Solanum elaeagnifolium) as a model organism [15].

Workflow Overview:

Detailed Methodology:

- Objective: To model the current and future distribution of an invasive species by analyzing its climatic niche, and to assess the potential for niche adaptation during invasion [15].

- Occurrence Data Compilation:

- Gather species occurrence data (georeferenced latitude and longitude) from both native and invasive ranges.

- Sources include online databases like the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF), scientific literature, and field surveys [15].

- For the silverleaf nightshade study, 9,536 occurrence points were used (7,860 from native ranges in the Americas and 1,676 from invasive ranges) [15].

- Environmental Data:

- Obtain global raster layers of bioclimatic variables (e.g., annual mean temperature, precipitation seasonality, temperature extremes) from sources like WorldClim.

- Include future climate projections from IPCC models (e.g., CMIP6) for specific greenhouse gas emission scenarios (SSPs) [15].

- Model Fitting:

- Use a machine learning algorithm, such as MaxEnt (Maximum Entropy modeling), to correlate species occurrence data with environmental variables.

- The model identifies the combination of climatic conditions that best define the species' fundamental niche in its native range [15].

- Niche Shift Analysis:

- Compare the environmental conditions in the invaded range to those in the native range to test for niche conservatism (similarity) or niche adaptation (divergence) [15].

- Statistically assess niche shifts using methods like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) on the environmental data.

- Projection and Validation:

- Project the calibrated model onto the current landscape of the invaded region and onto future climate scenarios to identify areas at high risk of invasion [15].

- Validate model performance using standard metrics (e.g., AUC - Area Under the Curve) and by checking if the model accurately predicts known invasive populations not used in model training [15].

Protocol: Multi-Species Interaction Modeling for Climate Impact Projection

This protocol involves creating computer models that simulate how climate change affects interactions between species, such as an invasive pest and its natural pathogen, to predict ecosystem-level impacts [16].

Workflow Overview:

Detailed Methodology:

- Objective: To project how climate change alters species interactions and leads to unexpected ecological consequences, using the spongy moth and its fungal pathogen as a case study [16].

- System Definition:

- Identify the key species in the interaction. In the referenced study, this was the invasive spongy moth (Lymantria dispar) and its biocontrol fungus (Entomophaga maimaiga) [16].

- Define the nature of the interaction (e.g., host-pathogen, predator-prey).

- Climate Data Integration:

- Use statistically downscaled climate data to obtain high-resolution, local projections of temperature and precipitation for the study region. This provides more accurate inputs than large-scale global models [16].

- Model Parameterization:

- Develop a mathematical model (e.g., a system of differential equations) that describes the population dynamics of the species involved.

- Incorporate climate variables as factors that directly influence key biological rates. For example, the model should reflect that the survival and transmission of the E. maimaiga fungus are highly dependent on cool, moist conditions [16].

- Parameterize the model with field-collected data on population sizes, infection rates, and climate-dependent mortality [16].

- Simulation and Analysis:

- Run the model under historical climate conditions and future climate scenarios to project changes in population sizes and interaction outcomes.

- Conduct sensitivity analyses to determine which parameters or climate variables have the largest effect on the model's predictions [16].

- Output and Interpretation:

- Key outputs include forecasts of pest population density, defoliation rates, and the efficacy of biological control under future climates [16].

- The spongy moth model predicted that hotter, drier conditions would drastically reduce fungal infection rates, leading to larger moth outbreaks and increased forest defoliation [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Technologies for Ecosystem Threat Research

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Low-Power Autonomous Sensors | Core component of distributed networks; continuously monitors acoustic, visual, and environmental variables (e.g., temperature, humidity) in remote locations with minimal human intervention [13]. |

| Bioacoustic Monitoring Systems | Deploys hydrophones (aquatic) or microphones (terrestrial) to record species vocalizations; used for species identification, behavioral studies, and estimating population density through passive acoustic monitoring [14]. |

| AI/Machine Learning Algorithms | Processes large, complex datasets from sensors and imagery; enables automated species identification from calls and images, pattern recognition, and predictive modeling of species distributions [13]. |

| Uncrewed Aerial Systems (Drones) | Provides aerial perspective for population counts, habitat mapping, and measuring individual animals; can also be used to deploy sensor tags on large cetaceans, minimizing stress to the animal [14]. |

| Animal-Borne Telemetry Tags | Tracks animal movement, behavior, and physiology via GPS, satellite, or acoustic signals; provides data on migration, habitat use, and dive patterns for highly migratory species [14]. |

| Climatic Niche Models (e.g., MaxEnt) | Correlates species occurrence data with environmental variables to predict potential geographic distribution under current and future climate scenarios, informing invasion risk [15]. |

| 'Omics Technologies (Genomics, Metagenomics) | Used in advanced sampling to assess genetic diversity, population structure, diet from fecal samples, and overall ecosystem health through environmental DNA (eDNA) analysis [14]. |

| Passive Acoustic Cetacean Map | A public, interactive data tool that displays near-real-time detections of whale and dolphin calls; used to inform dynamic management measures, such as vessel slow zones, to reduce ship strikes [14]. |

Ecosystem services—the critical benefits that nature provides to humanity—are under unprecedented threat. These services, which include carbon sequestration, water purification, soil retention, and food production, form the foundation of human well-being and economic stability. This document frames these pressing challenges within the context of a broader thesis on technological applications for identifying threats to protected ecosystems. It provides researchers, scientists, and environmental professionals with structured data, detailed protocols, and specialized toolkits to monitor, quantify, and address risks to these vital systems. The content synthesizes the most current research findings to deliver actionable methodologies for ecosystem risk assessment.

Quantifying the Status of Key Ecosystem Services

Global Carbon Sinks in Decline

Table 1: Global Forest Carbon Sink Capacity (2001-2024)

| Metric | Historical Average | 2023-2024 Status | Key Drivers & Observations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Annual CO₂ Absorption | ~30% of human emissions | ~25% of human emissions | Persistent deforestation and extreme fires [17]. |

| Primary Emissions Source | Agriculture (53% of emissions since 2001) | Fires (2.5x typical emissions) | Emissions from agriculture have risen steadily; 2023-204 fire surge was extraordinary [17]. |

| Regional Status Examples | |||

| Canada & Bolivia Forests | Net Carbon Sink | Net Carbon Source | Intensifying wildfires, often burning carbon-rich peatlands [17]. |

| Eastern U.S. Forests | Strong Net Sink | Robust Net Sink (but uncertain future) | Legacy of re-growth on abandoned farmland; now facing new climate stressors [17]. |

Ecosystem Service Supply-Demand Mismatch

Contemporary risk assessments highlight that ecological risk stems not just from environmental degradation, but from a growing mismatch between the supply of ecosystem services and human demand. A 2025 study on Xinjiang, China, exemplifies this approach by quantifying four key services over two decades [18] [19].

Table 2: Ecosystem Service Supply-Demand Dynamics in Xinjiang (2000-2020)

| Ecosystem Service | Supply Trend | Demand Trend | Deficit Status | Spatial Pattern |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water Yield (WY) | 6.02 → 6.17 x 10¹⁰ m³ | 8.6 → 9.17 x 10¹⁰ m³ | Large & Expanding | Supply along rivers; demand in oasis cities [18]. |

| Soil Retention (SR) | 3.64 → 3.38 x 10⁹ t | 1.15 → 1.05 x 10⁹ t | Large & Expanding | [18] |

| Carbon Sequestration (CS) | 0.44 → 0.71 x 10⁸ t | 0.56 → 4.38 x 10⁸ t | Small & Shrinking | [18] |

| Food Production (FP) | 9.32 → 19.8 x 10⁷ t | 0.69 → 0.97 x 10⁷ t | Small & Shrinking | [18] |

Experimental Protocols for Threat Identification and Monitoring

Protocol 1: Spatial Assessment of Threats to Ecosystem Service Hotspots

This protocol, adapted from a 2018 Durban, South Africa case study, uses GIS to evaluate the risk that land-use change poses to ecosystem services, enabling proactive spatial planning [20].

- Application Note: This methodology is critical for integrating ecosystem services into local government decision-making, revealing tensions between short-term development and long-term sustainability.

- Required Tools: Geographic Information System (GIS) software with spatial analysis capabilities.

- Workflow Diagram:

- Methodology:

- Define Study Area Boundary: Delineate the administrative or ecological region for analysis.

- Map Ecosystem Service Hotspots: For each service of interest (e.g., carbon storage, water yield, sediment retention), model and map areas of high supply.

- Map Land-Use Change Threats: Digitize geospatial data for current and proposed land-use changes, including strategic development plans, zoning applications, and mining permits [20].

- Overlay and Spatial Analysis: Use GIS overlay operations (e.g., Intersect) to identify the spatial coincidence between ecosystem service hotspots and threatened areas.

- Calculate Threat Statistics: Quantify the total area and percentage of each ecosystem service hotspot facing transformation.

- Report for Decision-Making: Present findings in a spatial format accessible to planners and policymakers, highlighting high-risk zones requiring protection or mitigation.

Protocol 2: Monitoring, Reporting, and Verification (MRV) for Marine Carbon Dioxide Removal

As interest in marine carbon dioxide removal (mCDR) grows, this protocol outlines a framework for verifying its efficacy and ecological safety, a critical technological need for governing new climate solutions [21].

- Application Note: This MRV framework is essential for ensuring that emerging mCDR technologies (e.g., ocean alkalinity enhancement, seaweed farming) function as intended without creating new environmental problems. It is a prerequisite for responsible scaling and carbon crediting.

- Required Tools: Oceanographic sensors (for carbon, pH, temperature), satellite data, biogeochemical models, and autonomous vehicles for monitoring.

- Workflow Diagram:

- Methodology:

- Establish Baselines: Prior to project initiation, comprehensively measure the background state of carbon (dissolved inorganic carbon, pCO₂) and relevant ecological parameters (biodiversity, nutrient levels) in the project area and control sites [21].

- Implement mCDR Project: Deploy the chosen mCDR technology at scale.

- Monitor Key Parameters:

- Carbon Fluxes: Quantify the net additional carbon dioxide removed from the atmosphere and transferred into the ocean.

- Carbon Storage: Verify the amount of carbon sequestered, its location (e.g., water column, deep ocean, sediments), and estimate its longevity [21].

- Environmental Impact: Monitor for potential negative effects, such as changes in water acidity, oxygen depletion, or toxicity to marine life.

- Report Data: Compile all monitoring data into a transparent and standardized report.

- Independent Verification: An independent, accredited party must audit the report and data to verify the claimed carbon removal and confirm the absence of significant adverse effects before any carbon credits are issued [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools and Models for Ecosystem Service Threat Research

| Tool/Model Name | Type | Primary Function in Threat Identification |

|---|---|---|

| InVEST Model Suite | Software Suite | Models and maps the supply and economic value of multiple terrestrial, freshwater, and marine ecosystem services (e.g., water yield, carbon storage, habitat quality) [18]. |

| Global Forest Watch (GFW) | Online Platform | Provides near-real-time satellite data and alerts on global tree cover loss, fire activity, and associated carbon emissions [17]. |

| Geographic Information System (GIS) | Software Platform | The core technological environment for spatial data analysis, overlay, and visualization of threats to ecosystem service hotspots [20]. |

| Self-Organizing Feature Map (SOFM) | Algorithm | An unsupervised neural network used to identify complex, multi-dimensional ecosystem service bundles and their associated risk clusters from spatial data [18]. |

| Ocean Carbon Sensors | Physical Sensor | In-situ instruments that measure dissolved CO₂, pH, and other biogeochemical parameters critical for MRV of marine carbon [21]. |

Pollinators are fundamental to global ecosystems and agricultural production, providing a critical ecosystem service by enabling the reproduction of a vast majority of flowering plants and crops. However, bee populations and those of other pollinators are in decline due to pressures from diseases, pesticides, and climate change [22]. This decline represents a significant threat not only to biodiversity but also to global economic stability and human health. A study led by the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health estimates that inadequate pollination is already responsible for 427,000 excess deaths annually due to lost consumption of healthy foods and associated diseases [23]. This case study examines the quantified costs of this decline and outlines protocols for using advanced technology, particularly machine learning, to identify and mitigate these threats within protected ecosystems.

Quantitative Impact Assessment

The economic and agricultural dependency on insect pollination is immense, though its value varies significantly by region and agricultural specialization. The following tables consolidate key quantitative findings from recent studies.

Table 1: Global and National Economic Value of Insect Pollination

| Region / Country | Economic Value of Insect Pollination | Key Metrics and Context |

|---|---|---|

| Global | $195 - $387 billion [24] | Annual value of animal pollination to global agriculture. |

| United States | >$400 million [25] | 2024 value of paid pollination services on 1.728 million acres. |

| France | €4.2 billion [22] | Annual Economic Value of Insect Pollination (EVIP) against an Economic Value of Crop Production (EVCP) of €34.8 billion. |

| France (Vulnerability) | 12% [22] | Agricultural vulnerability rate to pollinator loss. |

Table 2: Agricultural and Health Impacts of Pollinator Decline

| Impact Category | Quantitative Finding | Context and Scale |

|---|---|---|

| Crop Production Loss | 3-5% loss of fruit, vegetable, and nut production [23] | Global estimate due to inadequate pollination. |

| Human Health | 427,000 excess deaths annually [23] | From lost healthy food consumption and associated diseases (heart disease, stroke, diabetes, certain cancers). |

| Nutrient Supply | Up to 40% of essential nutrients [24] | Proportion of essential nutrients in the human diet provided by pollinator-dependent crops. |

| Regional Vulnerability | Highest in Loire-Atlantique, France (€19,302.5/ha) [22] | Economic value of insect pollination per hectare; highlights regional disparities based on crop specialization. |

Key Drivers of Pollinator Decline

A global expert review identified the primary drivers of pollinator decline, ranking land management, land cover change, and pesticide use as the most consistent and important threats across nearly all geographic regions [26]. Pests and pathogens are also critical, particularly in North and Latin America. Climate change is a recognized driver, though experts expressed slightly less confidence in its current impact compared to the other top factors [26]. These drivers often interact, creating complex pressures on pollinator populations.

Technological Protocols for Identifying Threats

The integration of technology is crucial for moving from post-hoc mitigation to proactive conservation. Machine learning (ML) offers transformative potential for analyzing complex ecological data and identifying emerging threats [27].

Protocol: Machine Learning for Spatial Pollination Risk Assessment

*Objective: To model and predict spatial variations in economic vulnerability to pollinator decline at a fine scale (e.g., departmental or regional level).*

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Geographic Information Systems (GIS) Software: Platforms like ArcGIS or QGIS for managing and visualizing spatial data on land use, crop coverage, and environmental variables.

- Statistical Computing Software: R or Python with specialized libraries (e.g.,

mgcvin R for GAM,scikit-learnin Python for various ML algorithms). - Generalized Additive Models (GAMs): A class of ML models highly effective for capturing non-linear relationships between response and predictor variables [22].

Methodology:

- Data Collection: Compile a spatially explicit dataset for the target region. Essential data layers include:

- Dependent Variable: Economic Value of Insect Pollination (EVIP) per hectare, calculated using production data for major pollinator-dependent crops and their respective dependence ratios [22].

- Independent Variables: Data on land cover/use (e.g., percentage of land dedicated to fruit orchards, vegetable cultivation), climatic variables (temperature, precipitation), and soil type [22] [27].

- Model Training: Develop a GAM to identify the main drivers of spatial variation in EVIP. The model structure can be represented as:

EVIP ~ s(percent_fruit_vegetable_land) + s(temperature) + s(precipitation) + ...wheres()represents a smoothing function applied to each predictor to model non-linear effects. - Validation & Prediction: Validate the model using a portion of withheld data. The validated model can then be used to predict vulnerability in other regions with similar data or to forecast future shifts under different land-use or climate scenarios.

- Data Collection: Compile a spatially explicit dataset for the target region. Essential data layers include:

The workflow for this protocol is outlined in the diagram below.

Protocol: Landscape Genetic Analysis of Pollinator Connectivity

*Objective: To assess the impact of landscape structure and habitat fragmentation on pollinator population genetics and functional connectivity, identifying genetic bottlenecks.*

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS): For high-throughput genotyping of pollinator samples (e.g., using RADseq or whole-genome sequencing).

- Landscape Genetics Software: Programs like

ResistanceGAin R to optimize resistance surfaces. - Machine Learning Algorithms: Used to model complex relationships between landscape features and genetic differentiation.

Methodology:

- Sample Collection & Genotyping: Collect pollinator specimens from multiple sites across a fragmented landscape. Extract DNA and use NGS to generate genome-wide single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) data.

- Landscape Resistance Modeling: Create GIS-based hypotheses (raster layers) of how different landscape features (e.g., roads, urban areas, specific crops, natural habitats) may impede or facilitate pollinator movement. Assign initial resistance values to each land cover type.

- ML-Optimized Analysis: Use ML algorithms to test which resistance surface best explains the observed genetic distance between sampling sites. This involves iteratively adjusting resistance values to find the model that maximizes the correlation between landscape resistance and genetic differentiation.

- Identification of Critical Corridors: The optimized resistance map is used to model least-cost paths and circuit-based connectivity, pinpointing areas where habitat corridors are most needed to maintain gene flow.

The logical framework for this analysis is depicted in the following diagram.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Pollination Threat Identification

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function in Ecological Analysis |

|---|---|

| Generalized Additive Models (GAMs) | A machine learning technique ideal for identifying and modeling complex, non-linear relationships between drivers (e.g., land use) and pollination outcomes (e.g., economic value) [22] [27]. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) | Enables high-resolution genomic analysis of pollinator populations to assess genetic diversity, identify pathogens, and track population declines and connectivity [28]. |

| Remote Sensing Data (Satellite/UAV) | Provides large-scale, temporal data on land cover change, habitat fragmentation, and floral resource availability, which are critical inputs for spatial models [27]. |

| Resistance Surface Modeling | A landscape genetics tool used to hypothesize and test how different landscape features impede gene flow, thus identifying barriers and corridors for pollinator movement. |

| Geographic Information Systems (GIS) | The central platform for integrating, managing, analyzing, and visualizing all spatial data layers, from crop maps to climate data and model outputs [27]. |

The decline of pollinators is not merely an environmental concern but a multi-faceted crisis with documented economic costs in the billions of dollars and a direct, negative impact on global human health, contributing to hundreds of thousands of excess deaths annually [22] [23]. The drivers are complex and interlinked, dominated by land use and pesticide practices [26]. Addressing this crisis requires a paradigm shift from reactive to proactive strategies. The integration of advanced technologies, particularly machine learning and genomic tools, into ecological research provides a powerful "scientist's toolkit" for precisely identifying threats, predicting vulnerabilities, and designing targeted, effective conservation policies to safeguard these essential contributors to ecosystem and human health.

The Technological Arsenal: A Deep Dive into Tools for Ecosystem Threat Identification

The application of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) is transforming the field of ecological research, providing powerful new tools for identifying threats to protected ecosystems. These technologies enable researchers to move from reactive to proactive conservation strategies by automating the complex tasks of species identification and habitat analysis. By processing vast and complex datasets from sources like satellite imagery, drone footage, and acoustic sensors, AI-driven models such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and recurrent neural networks (RNNs) have demonstrated significantly higher accuracy, scalability, and efficiency compared to conventional ecological methods [29]. This document outlines specific application notes and experimental protocols for leveraging these technologies within a research context focused on preserving biodiversity and ecosystem integrity.

Quantitative Performance Data

The transition from traditional ecological surveys to AI-powered monitoring represents a substantial leap in capability and efficiency. The following table summarizes key performance improvements estimated for the year 2025, illustrating the transformative impact of AI [30].

Table 1: Traditional vs. AI-Powered Ecological Monitoring (2025 Estimates)

| Survey/Monitoring Aspect | Traditional Method (Estimated Outcome) | AI-Powered Method (Estimated Outcome) | Estimated Improvement (%) in 2025 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vegetation Analysis Accuracy | 72% (manual species identification) | 92%+ (AI automated classification) | +28% |

| Biodiversity Species Detected per Hectare | Up to 400 species (sampled) | Up to 10,000 species (exhaustive scanning) | +2400% |

| Time Required per Survey | Several days to weeks | Real-time or within hours | -99% |

| Resource (Manpower & Cost) Savings | High labor and operational costs | Minimal manual intervention, automated workflows | Up to 80% |

| Data Update Frequency | Monthly or less | Daily to Real-time | +3000% |

Core AI Technologies and Their Applications

AI-powered ecological monitoring is built upon a suite of interconnected technologies that enable comprehensive data collection and analysis [30].

- Artificial Intelligence & Machine Learning: At the core, machine learning algorithms, including CNNs and RNNs, are trained on massive datasets comprising satellite imagery, drone footage, and sensor readings [29] [30]. These models automate the identification of plant and animal species, detect invasive organisms, and analyze vegetation patterns and environmental stressors with high precision.

- Satellite Imaging & Multispectral/Hyperspectral Sensors: High-resolution satellites provide large-scale, high-frequency imagery over vast expanses. AI processing of this data enables dynamic habitat mapping, assessment of plant health and growth patterns, and early detection of stressed vegetation, pests, and diseases [30].

- Drone-Based Sensing: Drones offer a complementary, fine-scale perspective at the field or tree level. AI algorithms can process drone-captured imagery in near real-time to automate fine-scale mapping of crop growth, pest outbreaks, and invasive species encroachment, detecting subtle stressors invisible to satellites [30].

- IoT Devices & Real-Time Data Streams: Distributed Internet of Things (IoT) sensors deployed across fields and forests continuously monitor microclimates, soil moisture, temperature, and water quality. When integrated with AI, this data stream empowers proactive and adaptive management based on emerging threats [30].

Experimental Protocols for Automated Species Identification

Protocol 4.1: AI-Driven Biodiversity Survey Using Camera Traps

Objective: To autonomously monitor and identify terrestrial mammalian species within a protected area to assess population trends and detect poaching activity.

Materials:

- Network of infrared-triggered camera traps.

- GPS units for geolocating camera placements.

- Pre-labeled dataset of animal images for model training.

- Computing hardware (GPU-enabled workstation or cloud compute instance).

- AI software platform (e.g., TensorFlow, PyTorch) or specialized wildlife monitoring software (e.g., SMART) [31].

Methodology:

- Site Selection & Deployment: Systematically place camera traps across the study area along game trails, water sources, and clearings to maximize species detection. Record GPS coordinates for each unit.

- Data Acquisition: Configure cameras to capture still images or short video clips upon trigger. Collect data from SD cards on a monthly basis or transmit data remotely if capable.

- Data Pre-processing: Manually label a subset of the collected images (e.g., "leopard," "elephant," "human," "empty") to create a ground-truthed training and validation dataset. Augment data by applying rotations, flips, and contrast adjustments to improve model robustness.

- Model Training:

- Employ a pre-trained Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) model (e.g., ResNet, YOLO) using transfer learning.

- Replace the final classification layer with a new layer corresponding to the number of species classes in your study.

- Train the model on the pre-processed dataset, using 70-80% of the data for training and the remainder for validation. Monitor for overfitting.

- Model Deployment & Inference: Deploy the trained model to an analysis server. Process new images from the camera traps through the model to obtain species identification, count, and timestamp.

- Data Analysis & Reporting: Aggregate detection data to create temporal activity patterns for each species and spatial heat maps of animal presence. Integrate with patrol data in platforms like SMART to identify poaching hotspots and guide ranger deployments [31].

Protocol 4.2: Satellite-Based Habitat Mapping and Change Detection

Objective: To map and monitor land-use and land-cover changes, including deforestation and illegal encroachment, in a protected forest ecosystem.

Materials:

- Time-series of multispectral/hyperspectral satellite imagery (e.g., from Sentinel-2, Landsat, or commercial providers).

- GIS software (e.g., QGIS, ArcGIS).

- Cloud-based geospatial analysis platform (e.g., Google Earth Engine) or ML-enabled image analysis software.

Methodology:

- Image Collection: Acquire cloud-free satellite images for the study area over multiple time points (e.g., annually over a 5-year period).

- Pre-processing: Perform atmospheric and radiometric correction on all images to ensure consistency across the time series.

- Labeling: Manually delineate and label different land-cover classes (e.g., "Dense Forest," "Degraded Forest," "Agriculture," "Water," "Urban") on a subset of images to create a training dataset.

- Model Training & Classification:

- Train a machine learning classifier (e.g., Random Forest, Support Vector Machine) or a deep learning semantic segmentation model (e.g., U-Net) on the labeled data.

- Use the trained model to classify the entire study area for each time point in the series.

- Change Detection: Compare the classified maps from different years using a change detection algorithm to identify pixels that have changed from one land-cover class to another.

- Validation: Conduct field visits or use high-resolution aerial imagery to validate the accuracy of the change detection results.

- Reporting: Quantify the area and rate of deforestation or other habitat loss. Report the geolocations of major change areas to relevant authorities for intervention.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the generalized, iterative workflow for an AI-powered ecological monitoring project, from data acquisition to conservation action.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Resources for AI-Powered Ecological Research

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Multispectral/Hyperspectral Sensors | Capture image data beyond the visible spectrum (e.g., near-infrared) deployed on satellites or drones. Critical for assessing plant health, water stress, and biomass [30]. |

| Acoustic Monitoring Devices | Record environmental audio. Used with AI audio recognition models to identify species by calls (e.g., birds, frogs) and detect threats like gunshots or chainsaws [31]. |

| Camera Traps | Passive, motion-activated cameras for capturing wildlife imagery. Provide the primary data source for training and deploying AI models for species identification and behavioral analysis [31]. |

| IoT Environmental Sensors | Measure hyperlocal parameters like soil moisture, temperature, and water quality. Data streams are integrated with AI for real-time ecosystem health monitoring and predictive modeling [30]. |

| Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) Models | A class of deep learning algorithms exceptionally effective for analyzing visual imagery. The core technology for automating image-based species identification and habitat mapping from camera traps and satellites [29]. |

| Spatial Monitoring & Reporting Tool (SMART) | A software platform that employs AI algorithms to analyze patrol and sensor data. Used to identify poaching hotspots and optimize the deployment of rangers in protected areas [31]. |

| GPU Computing Resources | Graphics Processing Units are essential for efficiently training complex deep learning models on large datasets of images or audio, significantly accelerating the research lifecycle. |

The escalating threats to protected ecosystems from climate change, habitat loss, and human activity necessitate advanced monitoring solutions [32]. Satellite and drone remote sensing technologies have emerged as powerful "Eyes in the Sky," enabling researchers to monitor vast and inaccessible habitats with unprecedented precision, frequency, and scale. By leveraging artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML), these technologies are revolutionizing how scientists identify, analyze, and respond to ecological threats, providing critical data for conservation policy and ecosystem management [30] [33]. This document outlines application notes and experimental protocols for implementing these technologies within a research framework focused on threat identification in protected ecosystems.

Modern habitat monitoring leverages a synergy of platforms, each with distinct advantages in spatial resolution, coverage, and data type.

Table 1: Platform Comparison for Habitat Monitoring

| Platform | Spatial Resolution | Coverage Area | Key Applications | Primary Sensors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Satellites (e.g., Sentinel, Landsat) | 10m - 30m | Continental to Global | Long-term land cover change, deforestation tracking, large-scale biodiversity assessment [30] [32] | Multispectral, Hyperspectral, Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) |

| Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs/Drones) | Centimeter-level | Local to Landscape | Fine-scale species mapping, micro-habitat structure, post-disturbance assessment, validation of satellite data [33] [34] | RGB, Multispectral, Hyperspectral, Thermal |

The integration of AI, particularly machine and deep learning, has led to a paradigm shift in data analysis, offering substantial improvements over traditional survey methods.

Table 2: Quantitative Impact of AI-Powered Monitoring vs. Traditional Methods

| Survey/Monitoring Aspect | Traditional Method (Estimated Outcome) | AI-Powered Method (Estimated Outcome) | Estimated Improvement (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vegetation Analysis Accuracy | 72% (manual identification) | 92%+ (automated classification) [30] | +28% |

| Biodiversity Species Detected per Hectare | Up to 400 species (sampled) | Up to 10,000 species (exhaustive scanning) [30] | +2400% |

| Time Required per Survey | Several days to weeks | Real-time or within hours [30] | -99% |

| Resource (Manpower & Cost) Savings | High labor and operational costs | Up to 80% savings [30] | ~80% |

Experimental Protocols

This section provides a detailed workflow for a typical habitat monitoring study, from data acquisition to model deployment.

Protocol 1: Multi-Scale Habitat Classification and Threat Mapping

Application Note: This protocol is designed for classifying habitat types (e.g., wetland complexes, forest health) and identifying anomalies like illegal logging or vegetation stress. It emphasizes data fusion, where satellite data provides the broad context and drone data enables fine-scale validation and feature extraction [32] [35].

Workflow Diagram: Habitat Classification & Threat Mapping

Detailed Methodology:

- Objective and Class Definition: Precisely define the habitat classes and threats of interest (e.g., 'Healthy Mangrove,' 'Stressed Moss,' 'Deforested Area,' 'Illegal Structure') [32]. Establish a hierarchical classification scheme.

- Multi-Scale Data Acquisition:

- Satellite Data: Download cloud-free or cloud-minimized scenes from open-source platforms (e.g., Copernicus Open Access Hub for Sentinel, USGS EarthExplorer for Landsat). Sentinel-1 (SAR) and Sentinel-2 (optical) fusion is highly recommended for improved accuracy in cloudy regions [32].

- UAV Data: Plan and execute UAV flights with appropriate sensors. For vegetation health, multispectral or hyperspectral sensors are superior to RGB [34]. Use a flight plan with >75% front and side overlap. Critical: Georeference imagery using Ground Control Points (GCPs) or RTK-enabled UAVs for high positional accuracy [34].

- Ground Truthing: Collect precise GPS coordinates and photographic evidence for each habitat class. This data is essential for training and validating the AI models.

- Data Pre-processing and Fusion:

- Satellite Imagery: Perform atmospheric, radiometric, and topographic corrections. Resample all data to a consistent spatial resolution.

- UAV Imagery: Process raw images through photogrammetric software (e.g., Agisoft Metashape, WebODM) to generate orthomosaics and digital surface models (DSMs).

- Data Fusion: Co-register the satellite and UAV-derived products into a single, unified geodatabase.

- Model Training and Validation:

- Feature Extraction: Calculate a suite of spectral indices (e.g., NDVI, NDWI, custom indices for specific vegetation) from the imagery to serve as model inputs [34].

- Data Splitting: Split the ground-truthed data into training (e.g., 70%), validation (e.g., 15%), and testing (e.g., 15%) sets.

- Model Selection and Training: Train multiple models, such as Random Forest (RF), Gradient Boosting machines (e.g., XGBoost, CatBoost), and Deep Learning models (e.g., U-Net). For complex landscapes, DL models consistently show modest but higher accuracy [32] [34].

- Validation: Validate model performance against the held-out test set using class-wise metrics like F1-score, precision, and recall, in addition to overall accuracy, to avoid bias from class imbalance [32].

- Map Generation and Analysis: Apply the best-performing model to the entire study area to generate a habitat classification map. Quantify the spatial extent of each class and identify areas of change or specific threats.

Protocol 2: AI-Powered Biodiversity and Species-Habitat Monitoring

Application Note: This protocol focuses on direct and indirect monitoring of species, particularly in wetland and forest ecosystems, by linking habitat maps to key biodiversity variables [32]. It leverages AI to analyze not only imagery but also acoustic data.

Workflow Diagram: Species-Habitat Monitoring

Detailed Methodology:

- Direct Species Observation:

- Data Collection: Deploy high-resolution satellites (e.g., WorldView) or UAVs for direct counting of large species [33]. Use camera traps and autonomous acoustic sensors for more elusive fauna [33].

- AI-Powered Analysis: Employ Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) like U-Net or pre-trained models (e.g., ResNet) to automatically identify and count species in imagery [34]. For acoustic data, use ML models to classify species based on their vocalizations [33].

- Outputs: Generate precise population counts, distribution maps, and behavioral activity patterns.

- Indirect Monitoring via Habitat Assessment:

- Habitat Suitability Modeling: Use the habitat maps generated in Protocol 1 as independent variables. Combine them with historical species occurrence data (from field surveys or citizen science) in models like MaxEnt or Random Forest to predict species distribution [32].

- Predictive Analytics: Utilize AI-driven predictive models to forecast potential future threats (e.g., poaching activities, disease outbreaks) or species distribution shifts under different climate scenarios [30] [33].

- Outputs: Produce habitat suitability maps and predictive threat maps that guide proactive conservation interventions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for Drone & Satellite Monitoring

| Category / Item | Specification / Example | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Platforms | ||

| Multispectral Satellite | Sentinel-2 (10-60m resolution, 5-13 bands) | Large-scale, recurring habitat and land cover change monitoring [32]. |

| SAR Satellite | Sentinel-1 (C-Band) | Penetrates cloud cover; monitors water levels, flooding, and vegetation structure [32]. |

| UAV/Drone | RTK-enabled Quadcopter or Fixed-Wing | High-resolution, on-demand data acquisition for fine-scale mapping and validation [34]. |

| Sensors | ||

| UAV-Hyperspectral Sensor | Captures 100s of narrow spectral bands | Detailed discrimination of vegetation species and health status beyond visible spectrum [34]. |

| UAV-Multispectral Sensor | Captures 4-10 specific bands (e.g., NIR, Red Edge) | Standard for vegetation health analysis (e.g., NDVI calculation) [30]. |

| Acoustic Recorder | Autonomous recording units (ARUs) | Passive monitoring of bird and amphibian populations via vocalizations [33]. |

| Software & Algorithms | ||

| Machine Learning Library | Scikit-learn, XGBoost, CatBoost | For implementing Random Forest and Gradient Boosting models for classification [32] [34]. |

| Deep Learning Framework | TensorFlow, PyTorch | For developing and training complex models like U-Net for image segmentation [34]. |

| Photogrammetry Software | Agisoft Metashape, WebODM | Processes UAV RGB/multispectral imagery into orthomosaics and 3D models [34]. |

| GIS Software | QGIS, ArcGIS Pro | Platform for data integration, spatial analysis, and final map production. |

| Ancillary Equipment | ||

| Ground Control Points (GCPs) | High-contrast markers (e.g., 1m x 1m) | Provides precise georeferencing for UAV imagery, improving spatial accuracy [34]. |

| GNSS/GPS Receiver | RTK or PPK GPS system | Provides high-accuracy (<5cm) location data for GCPs and field validation points [34]. |

| Spectral Validation Target | Calibrated reflectance panel | Used to perform radiometric calibration of UAV sensor data in the field. |

Bioacoustics, the science of investigating sound in animals and their environments, has emerged as a transformative tool for ecological monitoring and conservation enforcement. This field leverages the fact that many vital biological processes and anthropogenic threats produce distinct acoustic signatures. By capturing and analyzing these sounds, researchers and protected area managers can monitor biodiversity and detect illicit activities in near real-time, providing a powerful, non-invasive method for safeguarding ecosystems [36] [37]. The proliferation of sophisticated sensors and advanced analytical techniques like artificial intelligence (AI) has dramatically accelerated the capacity of bioacoustics to process vast datasets, offering unprecedented insights into the health and threats of protected areas [33] [38].

This document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for implementing passive acoustic monitoring (PAM). Framed within broader research on technological threats to protected ecosystems, it is designed for researchers, scientists, and professionals seeking to apply these methods for precise, data-driven conservation outcomes.

Core Applications in Conservation and Security

The application of bioacoustics technology spans two primary, interconnected domains: assessing ecological community composition and detecting illegal human activities that threaten ecosystem integrity.

Biodiversity and Ecosystem Health Assessment: Passive acoustic monitoring serves as a powerful tool for conducting biodiversity inventories and tracking ecological changes. By analyzing the soundscape—the combination of biological (biophony), geophysical (geophony), and anthropogenic (anthropophony) sounds—researchers can infer species richness, community composition, and behavioral patterns without the need for disruptive and labor-intensive physical surveys [39] [37]. This is particularly valuable in logistically challenging environments such as dense tropical rainforests [39] or the deep ocean [37].

Detection of Illegal Activities: A critical security application for bioacoustics is the real-time identification of threats such as illegal logging and poaching. Advanced algorithms can be trained to recognize the specific acoustic signatures of chainsaws, gunshots, and vehicles [38] [40]. When these sounds are detected, instant alerts can be dispatched to ranger patrols, enabling rapid intervention. A case study in Cameroon's Korup National Park demonstrated this capability, where an acoustic sensor grid provided precise data on spatial and temporal patterns of gun hunting activity [40].

Table 1: Quantitative Outcomes of Bioacoustics Applications in Various Ecosystems

| Ecosystem Type | Application Focus | Key Outcome | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tropical Forest (Korup NP, Cameroon) | Gunshot detection to evaluate anti-poaching patrols | Acoustic grid revealed a Christmas/New Year peak in gunshots and showed increased patrol effort did not lower hunting activity, challenging conventional metrics. | [40] |

| Atlantic Forest (Caparaó NP, Brazil) | Avian species richness assessment | 98 bird species detected; greater richness in semi-deciduous seasonal forest vs. ombrophilous montane forest; gunshots also identified. | [39] |

| Tropical Rainforest (Global) | Real-time detection of illegal logging | AI-powered systems identify chainsaw and truck sounds, sending immediate alerts to rangers' mobile applications. | [38] |

| Marine Environments (Temperate/Tropical) | Biodiversity and habitat use monitoring | Revealed previously unknown year-round presence of critically endangered North Atlantic right whales in mid-Atlantic areas. | [37] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

The effective implementation of a bioacoustics monitoring program requires meticulous planning, from initial hardware deployment to final data interpretation. The following protocols outline a standardized workflow.

Protocol 1: Sensor Deployment and Field Setup

Objective: To establish a grid of autonomous recording units (ARUs) that provides comprehensive spatial coverage of the study area for continuous, long-term acoustic data collection.

Materials: Autonomous Recording Units (e.g., Song Meter SM3/4, Wildlife Acoustics; or Guardian devices from Rainforest Connection), external omnidirectional microphones, weatherproof housing, GPS unit, solar panels or high-capacity batteries, mounting equipment (posts, clamps), and data storage media (SD cards).

Methodology:

- Site Selection: Conduct a preliminary assessment to identify locations that maximize acoustic coverage of target areas (e.g., known animal corridors, regions with historical illegal activity, or representative habitat patches). Consider accessibility for maintenance.

- Grid Design: Design a sensor grid with spacing informed by the effective detection range of the specific sounds of interest (e.g., ~1.2 km for gunshots [40]; 50-100 m for bird vocalizations in dense forest [39]). Use a geographic information system (GIS) to optimize placement.

- Sensor Configuration:

- Mounting: Secure ARUs on fixed posts or trees, typically 1.5 - 2 meters above the ground [39]. Orient external microphones to cover multiple cardinal directions.

- Power: Connect to a reliable power source, preferably solar panels with battery backup for extended deployments.

- Settings: Program recording schedules. For biodiversity, a duty cycle (e.g., recording 5 minutes every 15 minutes) may suffice. For security, continuous recording or a trigger-based schedule for specific sounds (e.g., gunshots, chainsaws) is essential [38] [40]. Standard settings include a 44.1 kHz sampling rate and 16-bit depth to capture the full frequency range of target sounds [39].

- Synchronization: Synchronize all ARU clocks using a GPS to ensure accurate temporal analysis across the grid [39].

- Data Retrieval: Establish a regular schedule for retrieving audio data and maintaining equipment, which can be done physically or via automated cloud transmission if cellular or satellite networks are available [38].

Protocol 2: Data Analysis for Threat Detection and Biodiversity Assessment

Objective: To process and analyze acoustic data to identify target signals—either specific anthropogenic threats or biological vocalizations—and derive meaningful ecological or security insights.

Materials: High-performance computing workstation, acoustic analysis software (e.g., Raven Pro, Kaleidoscope), cloud computing resources, and tailored AI models or algorithms.

Methodology:

- Data Ingestion and Management: Transfer audio files from the field to a centralized, secure server or cloud storage. Implement a robust file-naming and metadata tagging system.

- Automated Signal Detection:

- Threat Detection: Apply pre-trained machine learning models, such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), to scan audio files for the distinct spectral signatures of chainsaws, gunshots, or vehicles [38].

- Biodiversity Assessment: Use automated recognition models to identify species-specific vocalizations (e.g., bird songs, whale calls) or calculate acoustic indices (e.g., Acoustic Complexity Index, Bioacoustic Index) as proxies for biodiversity [39] [37].

- Validation: Manually verify a subset of the automated detections by visually and acoustically inspecting spectrograms to calculate and refine the model's accuracy and minimize false positives/negatives [40].

- Alert System (For Threat Detection): Configure the analysis pipeline to automatically generate and send real-time alerts (e.g., via SMS or a dedicated mobile app) to relevant authorities when a confirmed threat sound is detected, including the location and time [38].

- Data Synthesis and Interpretation: Correlate acoustic detections with spatial, temporal, and environmental data (e.g., patrol effort, rainfall, moon phase) to model patterns of illegal activity or ecological trends [40] [39].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Successful bioacoustic monitoring relies on an integrated suite of hardware and software.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Bioacoustics Studies

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Example in Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Autonomous Recording Unit (ARU) | Hardware | Long-term, weatherproof field recording of soundscapes. | Song Meter SM3 deployed in Caparaó National Park, Brazil [39]. |

| Passive Acoustic Sensor | Hardware | Continuous audio capture in remote locations; often solar-powered. | 12-sensor acoustic grid in Korup National Park, Cameroon, for gunshot detection [40]. |

| "Guardian" Device | Hardware | Recycled smartphone-based recorder for real-time anti-logging monitoring. | Rainforest Connection devices used in rainforests [38]. |