From Data to Discovery: How GPS Tracking is Revolutionizing Animal Ecology and Conservation

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the applications, methodologies, and challenges of GPS tracking in animal ecology research.

From Data to Discovery: How GPS Tracking is Revolutionizing Animal Ecology and Conservation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the applications, methodologies, and challenges of GPS tracking in animal ecology research. It explores the technological foundations, from classic VHF to modern IoT networks like Sigfox, and details how fine-scale movement data informs our understanding of animal behavior, resource selection, and population dynamics. The content critically examines pervasive challenges, including high costs, small sample sizes, and ethical considerations, while also presenting a future outlook on emerging technologies such as robotic autonomous systems and advanced biologgers that measure physiology and environment. Aimed at researchers and conservation professionals, this review synthesizes how GPS-derived insights are directly applied to pressing issues in conservation, from human-wildlife conflict to climate change resilience.

The GPS Revolution: Unveiling the Hidden Lives of Animals

The field of wildlife telemetry has undergone a revolutionary transformation, evolving from simple leg bands to sophisticated satellite-linked systems that provide real-time data on animal movements across the globe. This technological progression has fundamentally expanded our understanding of animal ecology, enabling researchers to answer complex questions about migration, habitat use, and behavior that were previously inaccessible [1]. The convergence of multiple technologies has created an unprecedented capability to monitor wildlife, providing critical data for conservation strategies and biodiversity preservation in the face of escalating environmental threats [2]. This document outlines the key historical developments, current methodologies, and essential tools in wildlife telemetry, framed within the context of ecological research applications.

Historical Development of Wildlife Tracking Technologies

The evolution of wildlife tracking technology represents a story of increasing miniaturization, improved data accuracy, and enhanced remote monitoring capabilities. The table below summarizes the major technological milestones in this field.

Table 1: Historical Timeline of Wildlife Tracking Technologies

| Time Period | Technology | Key Innovations | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1800s | Bird Banding | Simple leg bands for individual identification [3] | Demonstrating philopatry in birds [3] |

| Early 1930s | Scale Clipping | Serial enumeration system using scarring patterns [3] | Individual identification of snakes [3] |

| 1940s | Radar & Isotope Analysis | Doppler radar for migration studies; Stable-isotope analysis of feathers [3] | Tracking migratory organisms; Determining breeding origins [3] |

| 1950s | Acoustic Telemetry | First acoustic telemetry equipment for marine life [3] | Studying fish and wildlife in marine habitats [3] |

| 1960s | VHF Telemetry | Miniaturized transistor-based radio transmitters; triangulation techniques [3] [1] | Tracking diverse species from birds to mammals [3] |

| 1970s | Satellite Telemetry (Argos) | Use of Argos Data Collection and Location System [1] | Tracking wide-ranging migratory species [1] |

| 1990s | GPS Integration | Microprocessor-controlled GPS units with data storage [1] | High-accuracy positioning for free-ranging animals [1] |

| 2000s-Present | Integrated Multi-System Collars | Combination of GPS, Argos, VHF, and sensor technologies [1] | Comprehensive monitoring of location, physiology, and behavior [1] |

Modern Wildlife Telemetry Systems

Contemporary wildlife tracking systems combine multiple technologies to optimize battery life, data accuracy, and transmission capabilities based on specific research requirements. Modern tracking collars represent the convergence of decades of technological refinement.

Table 2: Comparison of Modern Wildlife Tracking System Architectures

| System Type | Data Transmission Method | Positional Accuracy | Battery Life Considerations | Ideal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Store-on-Board GPS | Physical recovery required [1] | High (Differentially correctable) [1] | Extended life (no transmission power drain) [1] | Shorter-term studies where animal recapture is feasible [1] |

| GPS/Radio Link | Spread Spectrum (SST) data link on command [1] | High [1] | Moderate (periodic transmission) [1] | Medium-range studies with some researcher proximity needed [1] |

| GPS/Argos Satellite | Through Argos-NOAA satellite system [1] | High (with stored GPS positions) [1] | Shorter life (satellite transmission power intensive) [1] | Remote tracking without field researcher presence [1] |

| GPS/Iridium Satellite | Two-way communication via Iridium network [4] | High [4] | Programmable based on fix rate and transmission interval [4] | Global real-time tracking with remote reprogramming capability [4] |

| Automated Radio Telemetry | Fixed receiver networks detecting VHF signals [5] | Variable (improved with grid search algorithms) [5] | Extended life (low-power VHF transmission) [5] | Small species tracking; high-temporal resolution studies [5] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Deployment of GPS/Iridium Satellite Collars

Purpose: To reliably attach and monitor GPS/Iridium satellite collars on large terrestrial mammals for remote data collection.

Materials Required:

- G5-D Iridium/GPS collar or equivalent [4]

- Wildlink Comm. Module for programming [4]

- Appropriate capture and restraint equipment for target species

- Veterinary equipment for animal welfare monitoring during procedure

Procedure:

- Pre-Deployment Programming: Using the Wildlink Comm. Module and Windows-based software, program the collar parameters including GPS fix schedule (1-24 fixes per day in 1-hour increments), satellite transmission interval (4 hours to 7 days), VHF duty cycle, and mortality sensor settings [4].

- Animal Capture: Follow species-specific ethical capture protocols to safely restrain the animal. Monitor vital signs throughout the procedure.

- Collar Fitting: Secure the collar to the animal using the neoprene belting, ensuring proper fit (circumference between 31-102 cm) that allows for growth and natural movement without slippage or constriction [4].

- System Verification: Confirm that the collar is powered and transmitting properly before animal release.

- Data Monitoring: Access location data through the managed Iridium website (atsidaq.com) which provides data files in .txt and Google Earth-compatible .kml formats [4].

- Remote Reprogramming: As needed, modify programming parameters remotely via the Iridium website, including adjustments to GPS fix rate, mortality hours, and transmission intervals [4].

Protocol: Automated Radio Telemetry with Grid Search Localization

Purpose: To track small wildlife species with high temporal resolution using received signal strength (RSS) and grid search algorithms for improved spatial accuracy.

Materials Required:

- Miniaturized VHF transmitters (as light as 0.4g for small species) [6]

- Network of fixed radio receivers with overlapping detection ranges [5]

- Equipment for transmitter attachment (glue, collars, or harnesses tailored to species)

Procedure:

- System Calibration: Characterize the RSS versus distance relationship for the specific transmitter-receiver system using an exponentially decaying function: S(d) = A - B×exp(-C×d), where d is distance, A is the lower detectable RSS limit, B relates to maximum signal strength, and C describes signal drop-off rate [5].

- Transmitter Deployment: Affix appropriately sized VHF transmitters to study animals using species-appropriate attachment methods.

- Data Collection: Deploy networks of fixed receivers to continuously monitor for transmitter signals within the study area [5].

- Grid Search Implementation: Process raw RSS data using grid search localization:

- Divide the study area into a systematic grid

- For each grid cell, calculate the normalized sum of squared differences between measured RSS values and model-predicted RSS values using the formula: χ²ᵢ = [1/(N-1)]×Σ[(Sₖ-S(dₖᵢ))²/S(dₖᵢ)] where N represents receiver count, Sₖ is measured signal strength at receiver k, dₖᵢ is distance from cell i to receiver k [5]

- Identify the grid cell with the lowest χ² value as the most probable animal location

- Trajectory Mapping: Repeat localization for each transmission event to estimate movement paths through the study area over time [5].

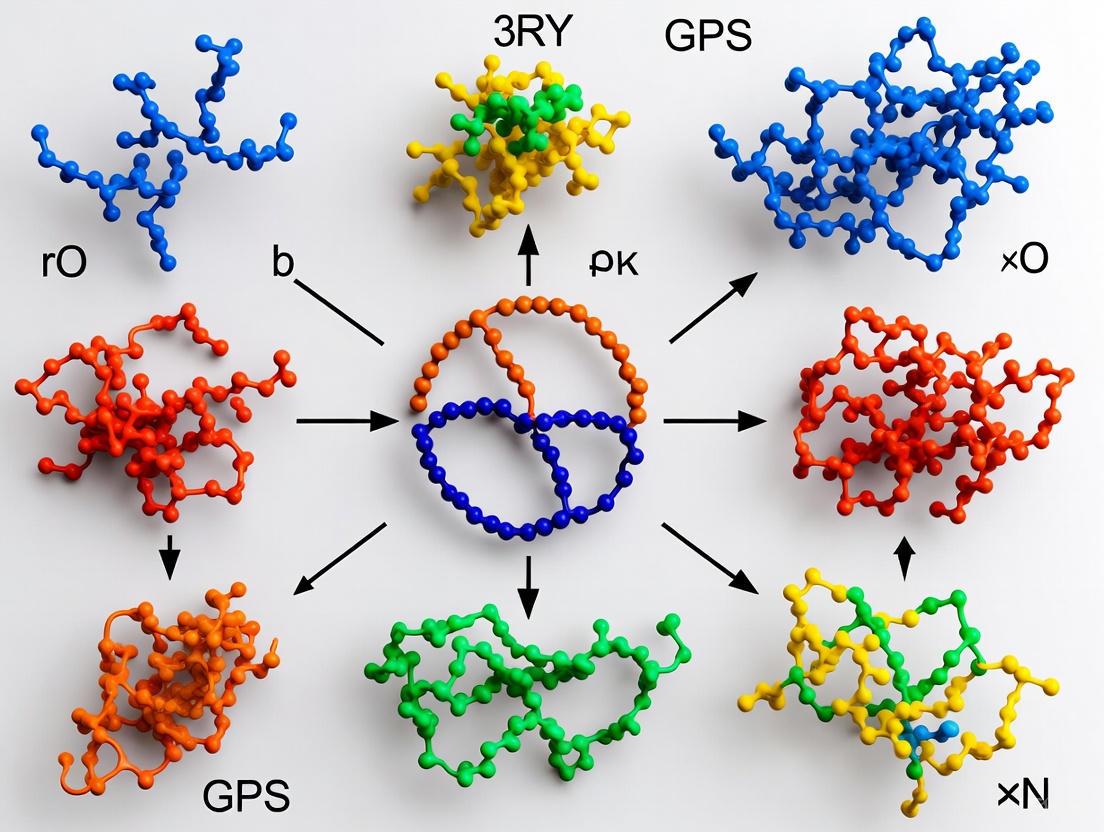

Visualization of System Architectures

Wildlife Telemetry System Architectures

The Researcher's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Wildlife Telemetry

| Item | Specifications | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| GPS/Iridium Collar | 500g weight; 4-year typical life @ 6 locations/day; Iridium transceiver for 2-way communication [4] | Large mammal tracking with remote data access and programming capability [4] |

| Micro VHF Transmitters | 0.4g-1g weight; 21-80 day battery life [6] | Tracking small birds, mammals, and reptiles where minimal payload is critical [6] |

| VHF Receiver & Antenna | Compact, robust design; omni-directional and Yagi antennas available [6] | Signal detection and manual tracking in field conditions [6] |

| Wildlink Comm. Module | Wireless UHF radio-link programming interface [4] | Remote programming of compatible collars without physical recovery [4] |

| Automated Receiver Stations | Fixed receivers with overlapping detection ranges [5] | Continuous monitoring in study areas for high-temporal resolution data [5] |

| Grid Search Localization Software | Custom algorithm for processing RSS data [5] | Improved spatial accuracy of ARTS location estimates [5] |

Global Positioning System (GPS) tracking devices have revolutionized animal ecology research by enabling scientists to monitor wildlife with unprecedented precision and detail. These devices function as sophisticated data loggers that record an animal's location, movements, and often additional environmental and physiological parameters over time. The core principle underlying all GPS wildlife tracking involves satellite trilateration, where the device calculates its position by measuring distances to multiple GPS satellites orbiting Earth [7] [8]. Modern GPS tracking systems belong to the broader category of Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS), which can include constellations like the U.S. GPS, Russia's GLONASS, and Europe's Galileo, providing greater satellite coverage and reliability [8]. For ecological studies, researchers deploy several types of tracking units—including collars for large mammals, tags for birds and reptiles, and implants for smaller species—each designed to minimize impact on the animal while collecting crucial data on behavior, migration, habitat use, and population dynamics [9].

The fundamental components of a wildlife tracking system include the GPS receiver that captures satellite signals, a power source (typically batteries, sometimes with solar augmentation), memory for data storage, and a transmission module for relaying collected information back to researchers [9]. Advanced units may also incorporate various sensors (e.g., accelerometers, temperature sensors) and attachment mechanisms tailored to specific species. These technologies have progressed significantly from early VHF radio tracking, which required researchers to be within line-of-sight of the animal, to today's systems that can autonomously collect and transmit locations from virtually anywhere on Earth, even in remote wilderness areas [9]. This technical capacity has transformed our understanding of animal ecology, providing insights into long-distance migrations, resource selection patterns, social interactions, and responses to environmental change that were previously impossible to document.

Fundamental Operating Principles

Satellite Trilateration and Positioning

The core positioning functionality of GPS wildlife tracking devices operates through a mathematical process called trilateration, which differs from triangulation by measuring distances rather than angles [8]. This process requires the device to receive signals from at least four GPS satellites to determine precise three-dimensional location (latitude, longitude, and elevation) [7] [8]. Each satellite in the network continuously transmits microwave signals containing its unique identifier, orbital parameters, and highly precise time stamps from onboard atomic clocks [7]. The GPS receiver in the wildlife tracking device calculates its distance to each satellite by measuring the time delay between signal transmission and reception, then uses these distances to pinpoint its location on Earth [7].

When a satellite signal is received, the device essentially determines that it is located somewhere on an imaginary sphere with a radius equal to the calculated distance from that satellite. With a single satellite, this provides little usable location information. When a second satellite signal is acquired, the possible locations are narrowed to the circle where the two spheres intersect. A third satellite reduces the possible locations to just two points in space, one of which is typically implausible (e.g., far out in space) and can be discarded [8]. In practice, a fourth satellite is essential for correcting clock discrepancies between the device's less precise internal clock and the satellites' atomic clocks, ensuring high location accuracy and enabling elevation calculation [8]. This entire process occurs automatically within the device's microprocessor, which computes the animal's position based on these satellite ranging measurements [7].

Data Collection and Transmission Protocols

Once the GPS device calculates its position, it follows specific protocols for data handling and transmission that vary depending on the tracking system design. The microprocessor collects the location data—typically including coordinates, timestamp, and often additional sensor readings—and stores this information in the device's internal memory [7]. Wildlife tracking systems employ two primary approaches for data retrieval: archival (passive) systems that store data for later recovery, and active (real-time) systems that transmit data remotely to researchers [7] [9].

Archival GPS trackers simply collect and store location data internally until researchers physically recover the device from the animal [7]. These systems are typically more affordable as they don't require cellular or satellite transmission capabilities, but they necessitate recapturing the animal to access the data, which presents logistical challenges and limits data access to the end of the monitoring period [7]. In contrast, active GPS tracking systems incorporate additional transmission technology—most commonly using worldwide GSM cellular networks where available, or satellite communication networks like Argos in remote areas—to send location data to researchers in near real-time [7] [9]. These systems typically include a SIM card and GSM transceiver similar to those in mobile phones, allowing the device to transmit the collected data over cellular networks to a central server where researchers can access it through specialized software [7]. This approach enables ongoing monitoring without needing to recapture the animal, though it typically involves monthly service fees for the cellular or satellite connectivity [7].

Table: Comparison of GPS Data Transmission Methods in Wildlife Research

| Transmission Method | Data Accessibility | Infrastructure Requirements | Typical Applications | Cost Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Archival/Passive | After device recovery | None for transmission | Short-term studies where recapture is feasible; small species | Lower hardware cost; no service fees |

| Cellular GSM Network | Near real-time | Cellular network coverage | Studies in areas with reliable cellular service | Monthly cellular service fees apply |

| Satellite Network (e.g., Argos) | Near real-time | Satellite communication capability | Remote areas, marine environments, wide-ranging species | Higher hardware cost; satellite service fees |

Technical Components and Specifications

Core Hardware Components

GPS wildlife tracking devices incorporate several essential hardware components that work in concert to capture, process, and transmit location information. The GPS receiver chipset serves as the core of the device, responsible for detecting satellite signals and performing the initial calculations to determine position [7]. These receivers vary in their sensitivity, power consumption, and ability to utilize multiple satellite constellations (GNSS capability), with more advanced chipsets providing better performance in challenging environments like dense forests or urban areas [8]. Research-grade tracking devices typically use receivers specifically designed for wildlife applications, balancing accuracy requirements with power constraints [9].

The power management system represents another critical component, typically centered around rechargeable or non-rechargeable batteries, sometimes augmented with solar panels for extended deployment [9]. Power requirements vary significantly based on tracking frequency, transmission method, and additional sensors, with device longevity ranging from weeks to several years depending on these configurations [9]. The memory capacity determines how much location and sensor data can be stored in archival units or buffered in transmitting units during communication blackouts. High-capacity devices can store tens of thousands of GPS points, with one documented case of a fox collar storing 13,000 locations over five years before recovery [9]. Additional sensors commonly integrated into modern wildlife trackers include tri-axial accelerometers for classifying behavior, temperature sensors for monitoring microclimate conditions, and wet/dry sensors for recording aquatic activity [9].

Device Form Factors and Attachment Methods

Wildlife tracking devices are available in various form factors specifically designed for different taxonomic groups and research objectives. GPS collars represent the most common form factor for medium to large terrestrial mammals, typically constructed from durable yet flexible materials with adjustable sizing to ensure secure yet comfortable fit [9]. These collars often incorporate drop-off mechanisms that automatically release the device after a predetermined time to enable recovery without recapturing the animal. For smaller mammals, birds, and reptiles, GPS tags provide lightweight alternatives, with specialized models available that weigh as little as 5 grams to minimize impact on the animal's mobility and behavior [9].

Harness systems offer an alternative attachment method for species where collars are impractical, particularly for birds, carnivores with cone-shaped heads, and some primates [9]. Ear tags provide another attachment option for certain ungulate and livestock species, while subcutaneous implants represent the most minimally invasive approach for some small mammals and aquatic species [9]. The selection of appropriate attachment method requires careful consideration of the species' anatomy, behavior, and potential impacts on the individual's welfare, with ideal attachments remaining secure throughout the study period while avoiding irritation or restriction of normal activities [9].

Table: Wildlife GPS Device Types and Typical Specifications

| Device Type | Target Species | Typical Weight Range | Primary Attachment Method | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPS Collars | Large mammals (e.g., elephants, bears, wolves) | 500g - 2000g+ | Neck collar | Must allow for seasonal neck size variation; often include drop-off mechanisms |

| Medium Collars | Medium mammals (e.g., deer, large carnivores) | 150g - 500g | Neck collar | Balance between battery life and weight restrictions |

| Lightweight Tags | Small mammals, birds | 5g - 150g | Harness, glue, or direct attachment | Miniaturization challenges; limited battery capacity |

| Implants | Small mammals, aquatic species | Varies | Surgical implantation | Requires specialized veterinary procedures; limits transmission capability |

Operational Workflow and Data Processing

Field Deployment Protocol

The deployment of GPS tracking devices on wildlife follows a systematic protocol to ensure both scientific validity and animal welfare. The process begins with careful device selection and configuration, matching the tracker specifications to the research questions and species biology [9]. Researchers must consider the device weight (typically recommended to be less than 3-5% of the animal's body weight), appropriate attachment method, sampling frequency, and expected deployment duration [9]. Prior to deployment, devices are programmed with the desired tracking schedule, which may include variable sampling intensities (e.g., more frequent fixes during active periods) to conserve battery life, and tested to ensure all components are functioning correctly.

The capture and handling phase requires specialized training and often involves collaboration with wildlife veterinarians to ensure animal safety [9]. Sedation may be necessary for larger or dangerous species, while some medium-sized animals can be fitted with devices using physical restraint alone. The attachment process must be performed efficiently to minimize stress, with proper fit verified to prevent injury while ensuring the device remains secure and positioned correctly for optimal GPS reception [9]. For collars, researchers typically ensure sufficient space for natural movement and seasonal size changes, while harness attachments require careful adjustment to avoid chafing. Post-release monitoring, sometimes using initial VHF tracking or remote data monitoring, helps confirm the animal has recovered normally and the device is functioning as expected.

Data Management and Analysis Pipeline

Once GPS devices begin collecting information, researchers implement a structured data processing pipeline to transform raw locations into meaningful ecological insights. The initial stage involves data retrieval either through periodic transmission via cellular or satellite networks or physical recovery of archival devices [7] [9]. Raw GPS data typically includes coordinates, timestamps, dilution of precision (DOP) values indicating position quality, and often additional sensor readings. This data is then subjected to quality filtering and cleaning to remove implausible locations resulting from signal interference, multipath errors (where signals bounce off structures or topography), or other sources of GPS error [10].

The cleaned data then undergoes processing and analysis using specialized software tools, which may include calculation of movement parameters (step lengths, turning angles, speed), home range estimation, habitat selection analysis, and identification of behavioral states [11]. Modern movement ecology analyses often employ sophisticated statistical models to identify patterns in the tracking data and relate them to environmental conditions and animal characteristics. The entire data management process requires careful documentation to ensure reproducibility, with particular attention to the filtering criteria and analytical choices that might influence research conclusions [10]. This structured approach to data handling ensures that the substantial investment in field data collection yields robust scientific insights into animal ecology and behavior.

GPS Wildlife Tracking System Workflow

Methodological Considerations and Best Practices

Accuracy Limitations and Environmental Factors

GPS tracking devices exhibit variable accuracy depending on numerous environmental and technical factors that researchers must consider when designing studies and interpreting data. Typical research-grade GPS collars achieve accuracy of 10-30 meters under optimal conditions, but several factors can degrade performance [12]. Physical obstructions such as dense forest canopy, topographic features, or artificial structures can block or reflect satellite signals, causing reduced accuracy or complete signal loss [7] [8]. This phenomenon, known as multipath error, occurs when GPS signals bounce off surfaces before reaching the receiver, creating positioning inaccuracies [8].

Atmospheric conditions including ionospheric delays and heavy cloud cover can also affect signal transmission and positioning accuracy [8]. In situations where GPS signals become completely blocked (e.g., indoors, caves, or dense vegetation), some devices can employ cellular tower triangulation as a fallback positioning method, though this approach provides significantly lower accuracy (down to approximately 100 meters in urban areas with high tower density, but potentially several kilometers in rural regions) [7]. The satellite constellation geometry at the time of positioning, expressed as Position Dilution of Precision (PDOP) values, further influences accuracy, with higher values indicating poorer satellite geometry and reduced positioning quality [12]. Researchers should document and report these accuracy limitations when publishing GPS tracking studies, and consider deploying units at stationary test locations to quantify site-specific accuracy before animal deployment [10].

Implementation Standards and Reporting Frameworks

The expanding use of GPS tracking in wildlife research has highlighted the need for standardized methodologies and reporting frameworks to ensure data quality, reproducibility, and comparability across studies. Recent systematic reviews have identified significant gaps in reporting of key methodological information, with only 12.1% of studies reporting the percentage of GPS data lost to signal failure, and merely 15.7% documenting the proportion of data removed as noise [10]. To address these shortcomings, researchers should adhere to emerging best practices that include detailed reporting of device specifications (make and model), sampling frequency, wear time, data validation procedures, and processing methodologies [10].

Specific recommendations include documenting the percentage of valid tracking data obtained after quality filtering, clearly defining location fix success rates, specifying any data imputation methods applied to fill small gaps in tracking data, and describing custom algorithms used for behavioral classification or movement analysis [10]. For studies linking GPS data with environmental information, researchers should report the spatial and temporal resolution of environmental datasets and the method of data linkage [10]. Establishing these reporting standards enables proper assessment of study reliability and facilitates more meaningful comparisons across different research projects and ecosystems. Furthermore, researchers should archive complete metadata including device programming parameters, deployment specifics, and any malfunctions or unusual occurrences during the tracking period to support long-term data usability and potential meta-analyses.

Table: Essential GPS Tracking Methodology Reporting Elements

| Reporting Category | Specific Elements to Document | Importance for Study Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Device Specifications | Make, model, firmware version | Understanding inherent device capabilities and limitations |

| Deployment Parameters | Species, attachment method, device weight relative to body mass | Assessing potential impact on animal behavior and welfare |

| Sampling Regime | Fix interval, schedule variations, total deployment duration | Understanding temporal resolution and potential sampling biases |

| Data Quality | Fix success rate, estimated accuracy, filtering criteria | Evaluating reliability of subsequent analyses |

| Processing Methods | Noise removal approach, data interpolation techniques, analytical algorithms | Ensuring reproducibility of analytical workflow |

The Researcher's Toolkit

Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful implementation of GPS wildlife tracking research requires access to specialized equipment and analytical tools. The core field equipment includes the GPS tracking devices themselves, which should be selected based on target species, research questions, and study environment [9]. Recommended suppliers include companies like Telemetry Solutions, which offers devices specifically designed for wildlife applications with features like lightweight construction (from 5 grams), extended battery life, and customizable tracking schedules [9]. Capture equipment appropriate for the target species is essential, which may include tranquilizer dart systems for large mammals, trap systems for smaller animals, or netting systems for birds and bats [9].

Data management and analysis tools form another critical component of the research toolkit. Specialized tracking software platforms enable researchers to manage, visualize, and perform initial filtering of GPS data [11]. For statistical analysis of movement data, programming environments like R with specialized packages (e.g., trackdf for data standardization, adehabitat for home range analysis, move for movement modeling) provide powerful analytical capabilities [11]. Data validation tools including reference GPS units for stationary accuracy testing and geographic information systems (GIS software) for relating animal movements to environmental layers are also essential components of a comprehensive wildlife tracking toolkit [10].

Wildlife GPS Research Toolkit Components

GPS collars, tags, and transmitters represent sophisticated data collection systems that have fundamentally transformed animal ecology research by providing unprecedented insights into animal movement, behavior, and ecology. These devices operate through the principle of satellite trilateration, calculating positions by measuring distances to multiple GPS satellites, then storing or transmitting this information for scientific analysis [7] [8]. The successful implementation of wildlife tracking studies requires careful consideration of device selection, attachment methods, sampling regimes, and data processing protocols to ensure both scientific validity and animal welfare [9] [10].

As GPS technology continues to advance, with improvements in miniaturization, battery efficiency, sensor integration, and data transmission capabilities, wildlife tracking will likely yield even deeper insights into animal ecology and conservation needs. Future developments may include even smaller devices for currently untrackable species, expanded sensor suites for comprehensive environmental and physiological monitoring, and improved data integration frameworks for relating individual movements to population-level processes and ecosystem dynamics. By adhering to methodological best practices and reporting standards, researchers can ensure that GPS wildlife tracking continues to generate robust, reproducible scientific knowledge to inform conservation strategies and address pressing challenges in animal ecology [10].

The advent of fine-scale, high-frequency spatio-temporal data has revolutionized animal ecology research. Moving beyond traditional tracking that sketched broad-scale movements in coarse strokes, this approach captures the intricate details of animal life, revealing behaviors, interactions, and environmental relationships that were previously invisible [13]. This shift is powered by advances in GPS-GSM telemetry and innovative analytical frameworks, enabling researchers to document movement paths with unprecedented detail, from the daily foraging patterns of waterfowl to the momentary decisions of a fox at a forest edge [13] [14]. These Application Notes detail the protocols, benefits, and essential tools for leveraging this transformative data type, framing it within the broader context of ecological discovery and conservation efficacy.

Key Benefits and Quantitative Evidence

The value of high-resolution tracking is demonstrated through its ability to correct prior assumptions, reveal novel behaviors, and provide more accurate data for conservation. The table below summarizes key findings from recent studies.

Table 1: Documented Benefits of Fine-Scale, High-Frequency Tracking Data

| Benefit | Species Studied | Key Quantitative Finding | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Revealing Fine-Scale Space Use | Dabbling Ducks (Gadwall, Mallard, Pintail) | Movements and space-use were far smaller than previously expected; Gadwall moved only 0.5-0.7 km, implying highly localized foraging and lower energy expenditure than predicted. [13] | |

| Detecting Short-Lived Behaviors | Red Fox | 43% of encountered linear features were tracked; median tracking duration was ~2 minutes, a behavior undetectable with conventional fix intervals. [14] | |

| Improving Mortality Cause Determination | Red Kite | A standardized protocol (LEAP) integrating GPS data, site investigation, and necropsy provided the highest quality mortality assessments in 64% of cases. 35% of cases were high-quality even without necropsy. [15] | |

| Informing Conservation & Management | Red Deer | GPS collars deployed on 22 stags and 6 calves in the Scottish Highlands provide data to manage deer densities, support habitat restoration, and balance ecological health. [16] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for High-Frequency GPS Burst Tracking

This protocol is designed to capture fine-scale movement behaviors, such as linear feature tracking (LFT), as demonstrated in red fox studies [14].

- Objective: To quantify short-duration, fine-scale spatial behaviors in a heterogeneous landscape.

- Equipment: Custom-built or commercial GPS-GSM transmitters with programmatic burst functionality.

- Tag Deployment:

- Capture & Handling: Adhere to strict ethical regulations. Ensure transmitter and harness package is 1.5-3% of the animal's body weight to minimize impact [13] [17].

- Attachment: Use back-mounted harnesses constructed of 5mm automotive elastic, secured with a knot and cyanoacrylic glue. Total handling time should not exceed 20-30 minutes per animal [13].

- GPS Programming:

- Burst Frequency: Program the transmitter to collect a "burst" of high-frequency GPS fixes at set intervals. For fox studies, a burst of fixes every 15 seconds was used [14].

- Burst Interval: Set the interval between the start of each burst to 10-20 minutes. This balances fine-scale data collection with battery longevity [14].

- Data Transmission: Utilize GSM networks for near real-time data transmission or satellite networks (e.g., Argos, Iridium, Kineis) for remote locations [18].

- Data Analysis:

- Path-Level Analysis: Treat each burst of high-frequency fixes as a continuous path.

- LFT Identification: Define an encounter with a linear feature (e.g., road, stream, forest edge). Calculate the animal's propensity to track the feature once encountered.

- Duration & Speed: Calculate the duration of LFT events and compare movement speeds across different linear feature types.

The workflow for implementing this protocol and analyzing the resulting data is as follows:

Protocol for Integrated Mortality Assessment (LEAP)

The LIFE EUROKITE Assessment Protocol (LEAP) provides a standardized framework for determining the cause, timing, and location of mortality in GPS-tagged birds, maximizing the scientific and conservation value of tracking data [15].

- Objective: To rapidly and accurately determine mortality causes for informed conservation action.

- Core Principle: Integrate three independent sources of information for a conclusive assessment.

- Procedure:

- GPS Tracking Surveillance:

- Monitor data for clusters of GPS locations indicating lack of movement.

- Use mortality sensors in tags if available. Aim for rapid carcass recovery to ensure freshness.

- Site Investigation:

- Upon locating the carcass, document all evidence: signs of struggle, predator tracks, scat, feathers/fur, presence of anthropogenic threats (power lines, roads, poisoned bait).

- Record the environmental context and take photographs.

- Necropsy:

- Perform a systematic necropsy by a trained veterinary pathologist.

- Look for evidence of trauma, disease, poisoning, or starvation.

- GPS Tracking Surveillance:

- Data Integration & Certainty Scoring:

- Integrate findings from all three sources (see workflow below). A conclusion is strengthened when multiple lines of evidence point to the same cause.

- Assign a certainty score (e.g., Confirmed, Highly Probable, Probable, Unconfirmed) to the mortality cause based on the quality and consistency of the evidence.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents & Essential Materials

Successful implementation of high-resolution tracking studies requires careful selection of hardware, software, and analytical tools.

Table 2: Essential Research Materials for Fine-Scale GPS Tracking

| Category | Item / Solution | Function / Specification | Example Use Case / Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hardware | GPS-GSM Transmitters | Core data collection unit. Must be programmable for burst frequency and fix rate. [13] [14] | Solar-rechargeable models extend battery life. [13] |

| Satellite Transmitters | Data transmission in areas without cellular coverage (e.g., Argos, Iridium, Kineis). [18] | Crucial for remote or marine species. [18] | |

| Multi-Sensor Biologgers | Logs additional data (e.g., temperature, pulse, salinity). [18] | Provides environmental & physiological context. [18] | |

| Software & Data | Movement Analysis Software (e.g., in R) | For path-level analysis, LFT quantification, and statistical modeling. [13] [14] | Custom scripts often required for novel analyses. |

| Spatial Data Platforms (e.g., Mapotic) | Visualizes movement data on interactive maps for public engagement and scientific analysis. [18] | Can increase public engagement by 25%. [18] | |

| High-Definition Spatial Data | Detailed maps of linear features (roads, streams, habitat edges). [14] | Essential for correlating movement with landscape. | |

| Ethical Compliance | Animal Handling Protocols | Guidelines to ensure welfare during capture, handling, and tagging. [17] | Must justify sample size and objective necessity. [17] |

| Color Contrast Analyzer (CCA) | Tool to ensure color choices in data visualization are accessible to all readers, including those with color vision deficiencies. [19] | Adheres to WCAG guidelines for inclusive science. [20] [19] |

Ethical and Practical Considerations

The power of fine-scale tracking comes with significant responsibility. Recent critiques highlight a trend of "trivialization," where nearly 40% of biologging projects on Iberian raptors resulted in no publications, and 39.6% remained entirely unpublished, failing to ethically justify the animal handling involved [17]. To counter this, researchers must:

- Justify Objectives and Sample Size: Prioritize conservation and critical research questions, and statistically justify the number of animals tagged to maximize knowledge gain while minimizing harm [17].

- Adhere to the 3Rs (Replace, Reduce, Refine): Consider non-invasive alternatives (e.g., camera traps, radar) where possible, and continually refine techniques to improve animal welfare [17].

- Ensure Data Publication and Sharing: Commit to publishing results in accessible formats to contribute to the collective scientific knowledge base [17].

Application Note: Advancing Ecological Research with Modern Tracking Technologies

Global Positioning System (GPS) tracking has revolutionized animal ecology research, enabling scientists to uncover hidden aspects of animal behavior, migration, and mortality patterns. The technology has evolved significantly from its public inception in the 1990s, with current systems leveraging thousands of satellites for global connectivity and near real-time data transmission [18]. This application note details how contemporary GPS and related tracking technologies are enabling critical research on traditionally challenging study subjects: oceanic fish, migratory songbirds, and wide-ranging mammals. We frame these advances within the broader thesis that technological innovation in animal telemetry is directly expanding the boundaries of ecological knowledge and conservation efficacy.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials for Wildlife Tracking

The following table catalogues key technologies and their specific applications in modern wildlife tracking research.

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Wildlife Tracking

| Technology/Solution | Primary Function | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| SHAD-TAGS+ [21] | Miniaturized acoustic fish tag | Monitoring previously "untaggable" small fish species and life stages; studying fish passage at hydropower dams |

| GPS-GSM Transmitters (e.g., Ornitela, E-obs) [22] | Collect and transmit location data via cellular networks | High-resolution tracking of migratory bird routes and mortality events |

| Satellite Networks (e.g., Argos, Iridium, Kinéis) [18] | Global data relay from remote locations | Transmission of animal location and sensor data from inaccessible areas (e.g., open ocean, deep wilderness) |

| Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) [23] | Satellite-based vessel detection independent of AIS | Monitoring illegal fishing activity in Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) and identifying "dark fleets" |

| Accelerometers (Integrated into tags) [24] | Measure dynamic body acceleration (ODBA) | Quantifying animal activity patterns and energy expenditure as a proxy for behavior |

| Data Compilation Pipelines [25] | Standardize and integrate disparate tracking datasets | Enabling large-scale, collaborative analyses across studies (e.g., for greater sage-grouse) |

Protocol 1: Tracking Small Aquatic Species with SHAD-TAGS+

Experimental Aim and Rationale

Understanding the behavior of small aquatic species and early life stages is critical for managing fisheries and mitigating the environmental impact of energy infrastructure. The SHAD-TAGS+ system was developed to overcome the historical size limitations of acoustic tags, which previously rendered many species "untaggable" [21]. This protocol details the deployment and use of this award-winning technology.

Materials and Equipment

- SHAD-TAGS+ acoustic transmitters (Pacific Northwest National Laboratory)

- Suitable surgical kit or external attachment apparatus

- Acoustic receiver array(s) deployed in study area

- AI-enabled data analysis workstation

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Tag Selection and Activation: Select the appropriately sized SHAD-TAGS+ model for the target species. The tag must not exceed the organism's recommended tag-to-body-mass ratio.

- Animal Capture and Handling: Capture the target species using methods appropriate to minimize stress (e.g., seining, trapping). Anesthetize the specimen if surgical implantation is required.

- Tag Deployment:

- Surgical Implantation: Aseptically implant the tag into the peritoneal cavity following standard surgical procedures.

- External Attachment: For species unsuitable for implantation, affix the tag externally using minimally invasive sutures or adhesives.

- Post-Treatment Recovery: Monitor the animal until it fully recovers from anesthesia and exhibits normal behavior before release at the capture site.

- Data Collection: Deploy a grid of stationary acoustic receivers to detect tag transmissions. Receiver spacing should be optimized for the study area's topography and the tag's transmission power.

- Data Analysis: Use AI-enabled software to process the high-resolution detection data. Analyze movement paths, residency times, and interaction with structures.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Leverage AI tools to decode complex movement patterns from the high-resolution detection data. Analyze the paths for behaviors such as upstream/downstream migration, approach and avoidance of dams or other structures, and diel activity patterns. The small size of the tags minimizes behavioral impacts, leading to more ecologically valid data.

Workflow Visualization

Figure 1: SHAD-TAGS+ deployment and data workflow.

Protocol 2: Validating Migration Counts and Mortality with GPS Telemetry

Experimental Aim and Rationale

Migratory bird counts at geographical bottlenecks are a long-standing method for estimating population trends. However, their underlying assumptions are rarely tested. This protocol uses GPS tracking data to validate these surveys and quantify flyway-scale mortality causes, revealing that human-induced mortality (61.8%) dominates over natural causes (23.1%) for large soaring birds [26].

Materials and Equipment

- GPS-GSM transmitters (e.g., 17-30g models from Ornitela, E-obs)

- Trapping equipment (e.g., cannon nets, mist nets)

- Database compilation pipeline for standardizing datasets [25]

- Geographic Information System (GIS) software

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Animal Capture and Tagging:

- Capture target species (e.g., raptors) using safe, species-appropriate methods (e.g., cannon-net at feeding sites [22]).

- Fit individuals with GPS-GSM transmitters using a well-fitted harness. Ensure total tag weight is <3-5% of body mass.

- Record individual metadata (species, sex, age, mass).

- Data Collection & Transmission:

- Program tags to collect high-frequency location fixes (e.g., several fixes per hour).

- Location data are transmitted via global GSM networks and satellite systems (e.g., Argos, Iridium).

- Mortality Detection and Classification:

- Flag tags transmitting stationary, non-migratory signals for extended periods as potential mortality events.

- Investigate mortality sites remotely via satellite imagery and/or conduct field visits.

- Classify causes of death into categories (e.g., human-induced: electrocution, poisoning, illegal killing; natural: predation, disease) with certainty levels (confirmed, very probable, possible) [26].

- Migration Route Analysis:

- Plot annual migratory routes for all tracked individuals.

- Calculate the proximity of each individual's migration path to established counting stations (e.g., Eilat, Batumi [22]).

- Data Integration and Validation:

- Use a compilation pipeline [25] to integrate tracking data with ground-based count data.

- Analyze whether the proportion of the tracked population passing by the count site is consistent between years.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Statistical models should assess how individual traits (age, sex, species) and environmental factors (wind, geography) influence the probability of a bird being counted. Analyze mortality data to identify spatial hotspots and taxon-specific vulnerabilities (e.g., electrocution is the leading cause for eagles [26]).

Workflow Visualization

Figure 2: GPS telemetry for migration and mortality studies.

Protocol 3: Assessing Capture and Tagging Effects on Mammals

Experimental Aim and Rationale

GPS tagging provides unparalleled data on mammal movement, but the capture, handling, and tagging process is a significant stressor that can alter post-release behavior, potentially biasing study results. This protocol outlines a method to quantify these effects using integrated GPS and accelerometer data, which is crucial for determining appropriate data exclusion periods [24].

Materials and Equipment

- GPS collars with integrated tri-axial accelerometers

- Species-specific capture equipment (e.g., box traps, darting systems)

- Chemical immobilization agents and veterinary monitoring equipment

- Software for calculating Overall Dynamic Body Acceleration (ODBA)

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Pre-Capture Planning:

- Obtain all necessary ethical and permitting approvals.

- Select collars that minimize weight and maximize animal welfare.

- Animal Capture and Handling:

- Capture animals using standardized methods (e.g., box trapping, helicopter darting).

- Minimize handling time and stress during the procedure.

- Record vital signs throughout chemical immobilization.

- Fit the GPS/accelerometer collar and release the animal at the capture site.

- High-Frequency Data Collection:

- Program the collar to collect GPS locations and accelerometer data at a high frequency (e.g., every 1-5 minutes) for at least the first 20 days post-release.

- Behavioral Metric Calculation:

- Daily Displacement: Calculate the straight-line distance between consecutive daily GPS locations.

- Overall Dynamic Body Acceleration (ODBA): Use accelerometer data as a proxy for activity and energy expenditure [24].

- Establishing a Baseline:

- Calculate the individual's long-term average for displacement and ODBA after the initial recovery period (e.g., using data from days 11-20).

- Quantifying Disturbance and Recovery:

- Disturbance Intensity: For each of the first 10 days, calculate the deviation in displacement and ODBA from the established baseline.

- Recovery Duration: Determine the number of days until an individual's displacement and activity metrics consistently return to within the baseline range.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Analyze data for interspecific and intraspecific patterns. Research shows over 70% of mammal species exhibit behavioral changes post-collaring, with herbivores often traveling farther and carnivores/omnivores reducing activity [24]. Recovery is typically brief (4-7 days), and individuals in high human-footprint landscapes recover faster [24]. Use these findings to inform study-specific data exclusion periods.

Key Quantitative Findings on Mammal Tagging Effects

Table 2: Summary of Post-Tagging Effects on Terrestrial Mammals (adapted from [24])

| Metric | Finding | Implication for Research |

|---|---|---|

| Affected Species | >70% of 42 studied species showed significant behavioral changes. | Tagging effects are the norm, not the exception, across taxa. |

| Initial Displacement | Increased by 6.9% ± 23.8% on day 1. | Initial locations may not represent typical movement. |

| Initial Activity (ODBA) | Decreased by 7.8% ± 19.2% on day 1. | Reduced activity may indicate recovery from stress/immobilization. |

| Recovery Duration | Most species recovered within 4-7 days. | Data from the first week should be treated with caution. |

| Key Influencing Factor | Animals in high human-footprint areas recovered faster. | Studies in remote areas may require longer data exclusion periods. |

From Movement to Management: Practical Applications in Ecology and Conservation

Global Positioning System (GPS) technology has revolutionized animal ecology by providing precise, high-frequency data on individual movement across space and time [10] [27]. This technological advancement enables researchers to move beyond static exposure measures, which are often tied to an animal's home location, thereby overcoming "stationary bias" and allowing for a more dynamic understanding of how animals interact with their environment [10]. The application of GPS tracking is fundamental to studying species-habitat associations, a cornerstone of ecological research and species conservation efforts [28]. By quantifying habitat selection, identifying movement corridors, and delineating home ranges, researchers can make informed decisions for protecting species from rapid habitat degradation and climate change [28]. This document provides detailed application notes and protocols for employing GPS technology within animal ecology research, framed within the broader context of a thesis on GPS tracking applications.

Analytical Frameworks for GPS Data

Relating animal movement data to environmental covariates requires selecting appropriate statistical models, each designed for specific research questions and data structures [28]. The choice of model significantly influences the ecological insights and conclusions drawn from the data.

Comparative Analysis of Statistical Models

Table 1: Comparison of statistical models for analyzing species-habitat associations with GPS data.

| Model | Primary Ecological Question | Data Scale & Requirements | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resource Selection Function (RSF) | Broad-scale habitat preference; relative probability of use [28]. | Relies on observed ("used") locations vs. random "available" locations within a home range (e.g., MCP) [28]. | Provides broad-scale information on species-habitat relationships; ease of implementation [28]. | Does not explicitly account for temporal autocorrelation in movement data [28]. |

| Step-Selection Function (SSF) | Fine-scale habitat selection in relation to movement [28]. | Requires high-frequency data; compares observed steps to random steps conditioned on the starting point [28]. | Explicitly accounts for movement and autocorrelation; infers habitat selection simultaneously with movement parameters [28]. | Requires relatively high-frequency data compared to RSFs [28]. |

| Hidden Markov Model (HMM) | How habitat relates to discrete behavioural states [28]. | Requires high-temporal resolution data to identify behavioural states [28]. | Links specific animal behaviours to environmental covariates; reveals state-specific habitat associations [28]. | Increased model complexity; requires sufficient data to identify behavioural states [28]. |

Workflow for Habitat Selection Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the generalized logical workflow for processing GPS data and selecting an appropriate statistical model for habitat selection analysis.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: GPS Data Collection and Pre-processing for Ecological Studies

Objective: To collect high-quality, raw GPS data from individual animals and prepare it for analysis by addressing common data quality issues [10] [29].

Materials:

- GPS tracking devices (e.g., collars, tags, implants)

- Data retrieval system (e.g., base station, satellite network)

- Computing software for data cleaning (e.g., R, Python)

Procedure:

- Device Deployment: Select an appropriate attachment method (e.g., collar, harness, ear tag, implant) tailored to the species' size, behavior, and habitat to ensure minimal impact and maximum data retrieval [27].

- Parameter Configuration: Set the GPS device's sampling frequency (e.g., every 10 seconds for fine-scale movement, hourly for broader patterns) and ensure the total wear time is sufficient for the research question [10].

- Data Retrieval: Obtain data via direct download, wireless transfer, or satellite systems, depending on the device and study environment [27].

- Data Validation and Cleaning:

- Assess Data Validity: Apply inclusion criteria (e.g., a minimum number of valid wear days or GPS points per day) to ensure data quality [10].

- Identify Signal Loss: Calculate and report the percentage of GPS data lost due to signal loss, often caused by environmental obstructions or device error [10].

- Filter Noise: Identify and remove implausible location points (noise) caused by multipath errors or low satellite connectivity. Report the method and threshold (e.g., maximum speed, altitude) used for noise identification and the percentage of data considered noise [10].

- Imputation of Missing Data: For gaps in the time series, consider using imputation methods (e.g., dynamic moving medians, last known location up to a time threshold) to fill missing values [10] [29].

Protocol 2: Implementing a Step-Selection Function (SSF)

Objective: To model fine-scale habitat selection by comparing the environmental conditions at observed locations to those at random locations an animal could have reached, conditional on its previous movement step [28].

Materials:

- Pre-processed GPS tracking data.

- Geospatial layers of environmental covariates (e.g., vegetation, elevation, prey diversity).

- Statistical software (e.g., R with the

amtpackage [28]).

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: From the cleaned GPS data, create observed "steps" (the vector between two consecutive fixes) and "turning angles".

- Generate Control Steps: For each observed step, generate a set of random steps (e.g., 10-20) that originate from the same starting point and have the same step length distribution but random turning angles. This creates a dataset of "available" locations [28].

- Extract Covariates: For the end point of each observed and random step, extract values from all relevant environmental covariate layers.

- Model Fitting: Fit a conditional logistic regression model to the case-control data (where observed steps are "cases" and random steps are "controls"). The model estimates selection coefficients (( \beta )) for each covariate, indicating strength and direction of selection [28].

- Interpretation: A positive ( \beta ) coefficient indicates selection for that habitat feature, while a negative coefficient indicates avoidance.

Protocol 3: Identifying Movement Corridors from GPS Tracks

Objective: To delineate areas of concentrated movement (corridors) that connect critical habitats, such as breeding and foraging grounds, for potential conservation.

Materials:

- Pre-processed GPS tracks from multiple individuals.

- A defined source and destination area (e.g., protected zones).

- Spatial analyst software (e.g., ArcGIS, R).

Procedure:

- Define End Points: Identify the core areas used by the population (e.g., home ranges, breeding sites) that are connected by movement.

- Generate Movement Paths: If data is from high-resolution GPS points, model individual movement paths as continuous corridors. For lower-resolution data, use the points to model a utilization distribution or resistance surface.

- Apply Corridor Model: Use a corridor modeling algorithm (e.g., Circuit Theory, Least-Cost Path analysis). Circuit Theory, implemented in software like Circuitscape, treats the landscape as an electrical circuit and models "current flow" between points, where corridors are areas of high current [28].

- Validate and Map: Compare model outputs with independent movement data, if available. Map the corridors, highlighting areas with the highest predicted movement flow for prioritization.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential materials and technologies for GPS-based wildlife ecology research.

| Item | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| GPS Collars & Tags | Devices containing GPS receivers and transmitters to collect and transmit location data. | Monitoring large mammals like elephants; tracking migration patterns of birds [27]. |

| VHF Transmitters | Radio transmitters for short-range tracking where GPS signals may be unreliable. | Detailed, close-range monitoring in dense forests or terrain [27]. |

| Satellite Telemetry Systems | Systems that use satellites to receive data from tracking devices for global monitoring. | Tracking wide-ranging marine species or long-distance migrations [27]. |

| Base Station/Data Downloader | A device used to remotely download stored data from a GPS tracker when in proximity. | Retrieving data from collars on animals that return to a known area (e.g., a den) [27]. |

| R Statistical Software | Open-source environment for statistical computing and graphics. | Implementing RSF, SSF, and HMM analyses using specialized packages (e.g., amt, momentuHMM) [28]. |

Data Presentation and Visualization

Best Practices for Reporting GPS Data and Methods

Transparent reporting of GPS data collection and processing methods is critical for reproducibility and cross-study comparison [10]. The following workflow outlines key reporting elements identified from a systematic review of best practices.

Quantitative Reporting Deficiencies: A systematic review revealed that critical methodological information is often under-reported. Only 12.1% of studies reported the percentage of GPS data lost to signal loss, and a mere 15.7% reported the percentage of data considered noise. Furthermore, 6% of studies did not disclose the GPS device model used [10]. Adhering to the best practices outlined in the diagram above is essential for improving research transparency.

Integrating high-resolution movement data with life history events is transformative for animal ecology, enabling researchers to link spatial patterns to critical biological processes like survival and reproduction. The advent of advanced GPS-GSM telemetry has revolutionized the field, allowing for the collection of detailed data on individual movement, behavior, and habitat use continuously and over extended periods [30] [31]. This protocol outlines a comprehensive methodology for deploying an animal movement database and analytical framework to remotely monitor survival and reproduction, framed within a broader thesis on GPS tracking applications in ecological research. This approach effectively converts the physical world of animal movement into a quantifiable digital model, facilitating powerful data analysis and visualization [32].

Application Notes: Core Concepts and Workflow

Linking movement to life history requires a structured data management and analysis pipeline. The core concept involves establishing a relational database to systematically store and link animal metadata, deployment information, and raw telemetry data, which can then be processed to extract biologically significant events [33].

The general workflow, as illustrated below, begins with data acquisition and proceeds through storage, processing, and analysis to ultimately link movement patterns to life history traits. This workflow ensures data integrity and enables sophisticated queries.

Key Life History Events from Movement Data

Advanced telemetry enables the remote identification of specific life history states. The following table summarizes key behavioral and movement patterns that serve as proxies for critical biological events.

Table 1: Interpretable Life History Events from Movement Data

| Life History Event | Movement/Behavioral Signature | Data Sources & Sensors | Ecological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natal Dispersal | Permanent movement from birthplace to first breeding site; one-way long-distance movement or gradual shift [30]. | GPS locations, accelerometry | Informs on gene flow, population structure, and species distribution [30]. |

| Reproduction (Egg Laying) | Transition to central-place foraging; characteristic inactivity patterns at a specific site [30]. | GPS, accelerometer sensor data | Accurately pinpoints the start of incubation and breeding site fidelity [30]. |

| Migration | Abrupt, directional, long-distance movement (>100 km/day) without return; seasonal timing [30]. | GPS time series | Defines migratory connectivity, timing, and wintering/summering ranges [30]. |

| Mortality | Complete and prolonged cessation of movement; GPS cluster location remaining static [33]. | GPS, mortality sensor (if equipped) | Provides critical data for survival rate estimates and cause-specific mortality. |

| Seasonal Range Establishment | Shift from transient to localized movements; establishment of a stable home range [30]. | GPS location clusters, kernel density estimates | Identifies key habitats for foraging, wintering, or pre-breeding. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Establishing a Relational Database for Telemetry Data

A robust relational database is the foundational component for managing complex telemetry data, preventing data silos and version control issues common in spreadsheet-based workflows [33].

3.1.1 Materials

- Database server (e.g., PostgreSQL with PostGIS extension) [33].

- Data tables (animals, devices, deployments, raw_gps, telemetry).

3.1.2 Procedure

- Database and Table Creation: Create a new PostgreSQL database and enable the PostGIS extension. Construct the core tables using SQL commands as defined below [33].

- Data Population:

- Insert records into the

animalstable for each study subject, including permanent ID, sex, age, and species [33]. - Insert records into the

devicestable for each transmitter, including unique serial number and manufacturer [33]. - Link animals and devices in the

deploymentstable, specifying theanimal_id,device_id, and accurateinserviceandoutservicedates [33].

- Insert records into the

- Data Ingestion and Parsing: Upload raw GPS data from vendors into the

raw_gpstable. Use an automatedINSERT...SELECTquery to parse and filter this data into thetelemetrytable, associating locations with the correctanimal_idand only including points within the deployment period [33].

Table 2: Essential Database Tables for Telemetry Data

| Table Name | Key Fields | Foreign Key Relationships | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| animals | id (PK), perm_id, sex, age, species |

Referenced by deployments.animal_id |

Master catalog of all study animals and their biological attributes [33]. |

| devices | id (PK), serial_num (UNIQUE), model |

Referenced by deployments.device_id |

Master catalog of all tracking devices [33]. |

| deployments | id (PK), animal_id (FK), device_id (FK), inservice, outservice |

Links animals and devices |

Tracks which animal carried which device and during what time period [33]. |

| raw_gps | id, device_id, timestamp, latitude, longitude, fix_attempt |

None (raw data from device) | Stores all downloaded GPS data before processing [33]. |

| telemetry | id, animal_id (FK), timestamp, location, deployment_id (FK) |

Links processed locations to an animal and its deployment | Stores clean, analysis-ready location data associated with a specific animal [33]. |

The data flow between these core tables is logical and sequential, ensuring data integrity from device registration to the creation of analysis-ready trajectories.

Protocol 2: Field Deployment and Data Collection for Raptors

This protocol is adapted from a study tracking Montagu's Harrier, demonstrating the practical application of these methods [30].

3.2.1 Materials

- Solar-powered GPS-GSM transmitters (e.g., Ornitrack-10, Ornitela) with accelerometer sensors [30].

- Permits for capture, handling, and tagging (e.g., in Italy, under Law 157/1992) [30].

- Field equipment for safe capture and handling.

3.2.2 Procedure

- Animal Capture and Tagging: Trap target animals (e.g., raptor chicks during the nestling period) under appropriate authorization. Equip individuals with transmitters, ensuring the device weight is a small fraction of body mass (<3-5%) [30].

- Data Acquisition: Configure transmitters to collect high-resolution GPS fixes (e.g., several fixes per hour) and accelerometer data. Data are transmitted via the GSM network to a server in near real-time [30].

- Data Validation: Conduct periodic field visits, potentially using drones with high-definition cameras, to visually confirm key life history events identified from the data, such as nest location and breeding status [30].

Protocol 3: Analytical Workflow for Identifying Life History States

The following workflow details the steps to transform raw location data into inferred life history events.

3.3.1 Materials

- GIS software (e.g., QGIS) [30].

- Statistical programming environment (e.g., R with

adehabitatLT,movepackages). - Cleaned data from the

telemetrytable.

3.3.2 Procedure

- Data Cleaning and Preparation: Import GPS data into GIS software. Project data to an appropriate coordinate system (e.g., UTM) for spatial analysis [30].

- Behavioral Phase Definition: Define movement phases using quantitative thresholds:

- Migration: Onset is an abrupt, directional movement >100 km/day without return; migration ends when this displacement stops for >10 days [30].

- Breeding: Characterized by central-place foraging. The active breeding phase begins with egg laying, identifiable via a distinct signature in accelerometer data [30].

- Natal Dispersal: Measured as the straight-line distance between the natal nest and the first breeding site [30].

- Spatio-temporal Analysis: Calculate home ranges (e.g., 95% utilization distribution) and core areas (50% UD) for each seasonal phase using kernel density estimation. Calculate total cumulative distance traveled over the tracking period [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This section details the essential materials, or "reagents," required for a successful telemetry study, from hardware to software.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Telemetry Studies

| Item Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| GPS-GSM Transmitters | Ornitrack-10 (Ornitela) | Solar-powered tags that collect high-resolution GPS locations and transmit data via cellular networks; essential for fine-scale movement and behavior studies [30]. |

| Relational Database | PostgreSQL with PostGIS extension | Serves as the central repository for all study data; ensures data integrity, enables complex spatial queries, and automates data processing workflows [33]. |

| Geographic Information System | QGIS | Open-source software for mapping locations, visualizing movement trajectories, and conducting spatial analyses (e.g., kernel density estimation) [30]. |

| Data Visualization Platforms | Animal Telemetry Network (ATN) Data Portal, Power BI | Web-based and desktop tools for creating interactive maps and dashboards to explore and present tracking data to diverse audiences [34] [35]. |

| Statistical Programming Environment | R (with ggplot2, adehabitatLT) |

Provides a flexible environment for conducting specialized movement analyses (e.g., segmentation, speed calculation) and generating publication-quality graphics [35]. |

The integration of movement data with life history events, facilitated by a structured database and analytical protocol, provides an unprecedented window into the lives of animals. This approach, as demonstrated by the detailed tracking of a Montagu's Harrier from natal dispersal to first reproduction, allows researchers to move beyond simple movement paths to understand the demographic consequences of animal movement [30]. This framework is vital for advancing ecological knowledge and formulating evidence-based conservation strategies.

The application of GPS tracking technology has fundamentally transformed animal ecology research, enabling an unprecedented, data-driven understanding of how wildlife responds to rapid environmental change [36]. This case study on the white stork (Ciconia ciconia) exemplifies the power of biologging—the use of animal-borne sensors—to move beyond simple movement trajectories and quantify fine-scale behavioral tactics, energy expenditure, and ultimate fitness consequences in human-modified landscapes [37]. White storks present a compelling model system as long-distance migrants that have increasingly become year-round residents in parts of Europe, a behavioral shift widely attributed to the availability of anthropogenic food subsidies [38] [39]. By integrating GPS data with accelerometry and environmental data, researchers can move from correlative observations to a mechanistic understanding of how human-driven resource shifts alter individual energy budgets, survival, and reproductive success, thereby illuminating the fundamental ecological processes governing population-level trends [40] [37].

Key Quantitative Findings

Research leveraging tracking technology has yielded critical insights into the behavioral and fitness outcomes of white storks exploiting anthropogenic landscapes. The tables below summarize the core empirical findings.

Table 1: Documented Behavioral Shifts and Associated Mechanisms in White Storks

| Behavioral Trait | Observed Shift | Proximate Mechanism | Key Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Migratory Behavior | Shortening of migratory distance or complete loss of migration (residency) [39]. | Reliance on predictable, non-seasonal anthropogenic food (e.g., landfill waste) [38]. | GPS tracks showing residency at sites with landfills versus traditional migration to Africa [39] [41]. |

| Foraging Ecology | Increased use of landfills, agricultural fields, and artificial water bodies [38]. | Reduced foraging time and effort due to dense, predictable food patches [37]. | Network analysis showing landfills as central, highly connected nodes in habitat use networks [38]. |

| Flight & Energetics | Age-related performance changes; adults fly in less-supportive conditions [42]. | Lifelong improvement in skill (e.g., exploiting challenging uplift) and changing motivation [42]. | High-resolution lifetime tracking data from 151 storks quantifying flight performance and energy expenditure [42]. |

Table 2: Fitness Consequences of Exploiting Anthropogenic Resources

| Fitness Component | Measured Effect | Method of Quantification | Notes and Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Juvenile Survival | Increased survival for individuals overwintering in Europe vs. Sub-Saharan Africa [39]. | Identification of mortality events via clustered GPS fixes and accelerometer data [39] [37]. | Longer migratory distance increases mortality risk; only ~30% of juveniles survive their first year [39]. |

| Adult Survival | Potentially higher for residents, but health trade-offs exist [37]. | Analysis of long-term tracking data and mortality events. | Ingested pollutants (e.g., plastics) at landfills pose a health risk [38]. |

| Reproductive Success | Enhanced nest survival linked to urban foraging [40]. | GPS tracking of breeding attempts linked to nest monitoring. | Benefit arises from release from calorie limitation due to reliable anthropogenic food [40]. |

| Energetic Costs | Reduced energy expenditure for residents and landfill foragers [37]. | Overall Dynamic Body Acceleration (ODBA) derived from accelerometers [37]. | Energetic savings can be allocated to reproduction and survival [37]. |

Experimental Workflow and Analytical Framework

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow from hypothesis formulation to data collection and analysis, which is central to modern biologging studies.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: GPS-Accelerometer Tracking and Energetics Estimation

This protocol details the methodology for capturing, tagging, and collecting data to link movement and behavior to energy expenditure [37].

Animal Capture and Tagging

- Capture: Target free-ranging white storks at nest sites during the breeding season or at foraging sites using established, safe methods.

- Device Attachment: Deploy a combined GPS-ACC logger as a backpack harness. Use Teflon or nylon harness material to minimize abrasion and ensure a secure but not restrictive fit. The device and harness should typically weigh <3% of the bird's body mass (approx. 3-4.5 kg [43]).

- Device Programming: Program the GPS logger to collect locations at a high temporal resolution (e.g., 1-5 minute intervals) to resolve fine-scale movement and foraging behavior. Synchronize the accelerometer to record at a high frequency (e.g., 20-40 Hz) on three axes (surge, heave, sway).

Data Collection and Management

- Remote Data Transfer: Use devices with UHF or satellite (Argos/GPS) data transfer capabilities for remote data download, or retrieve data via recapture or proximity-based download.

- Data Repository: Store and manage all raw data in a dedicated repository such as Movebank [38] [39], ensuring data integrity and facilitating open access.

Data Processing and Analysis

- Data Filtering: Filter GPS and ACC data for outliers and errors based on speed, fix accuracy, and sensor diagnostic information [38].

- Energetics Proxy Calculation: Calculate the Overall Dynamic Body Acceleration (ODBA) from the accelerometer data as a validated proxy for energy expenditure [37] [24]. ODBA is computed by summing the dynamic components (total acceleration minus the static gravity component) of the three acceleration vectors over a specified time window.

- Behavioral Classification: Use machine learning models (e.g., Hidden Markov Models) to classify high-resolution GPS and ACC data into discrete behavioral states (e.g., foraging, flying, resting) [36].

Protocol: Spatial Network Analysis for Habitat Connectivity

This protocol uses GPS tracking data to quantify how white storks functionally connect landscapes, particularly between anthropogenic and natural habitats [38].

Node and Link Definition

- Land Use Map: Overlay GPS tracks on a land-use map (e.g., Corine Land Cover). Classify habitats into distinct types (e.g., landfill, urban, marsh, rice field, lake) [38].

- Node Creation: Define "nodes" as distinct, spatially explicit habitat patches. Merge adjacent polygons of the same habitat type if they are within a specified distance (e.g., 10 km) to avoid network overcomplication [38].

- Link Creation: Define a "link" as a direct flight by an individual stork between two nodes.

Network Construction and Analysis

- Network Metrics: Calculate standard network metrics to identify important habitats.

- Degree Centrality: The number of direct connections a node has to other nodes.

- Betweenness Centrality: The number of shortest paths that pass through a node, identifying it as a critical connector.