From Data Deluge to Discovery: A Researcher's Guide to Managing Large Bio-Logging Datasets

The explosion of bio-logging technology provides unprecedented insights into animal behavior, physiology, and environmental interactions, but also presents significant big data challenges.

From Data Deluge to Discovery: A Researcher's Guide to Managing Large Bio-Logging Datasets

Abstract

The explosion of bio-logging technology provides unprecedented insights into animal behavior, physiology, and environmental interactions, but also presents significant big data challenges. This article offers a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on handling large, complex bio-logging datasets. It covers foundational principles, modern analytical methodologies like machine learning, crucial optimization techniques for performance and data quality, and rigorous validation frameworks. By addressing the full data lifecycle, this guide aims to empower researchers to transform vast data streams into robust, reproducible ecological and biomedical discoveries.

Understanding the Scale and Challenge of Bio-Logging Big Data

Frequently Asked Questions

What defines a 'large' bio-logging dataset? A bio-logging dataset is considered "large" based on the Three V's framework: Volume, Velocity, and Variety. The Volume refers to the sheer quantity of data, which can quickly accumulate to billions of data points from high-resolution sensors [1]. Velocity is the speed at which this data is generated and must be processed, sometimes in near real-time [2]. Variety refers to the diversity of data types collected, from location and acceleration to video and environmental parameters, often in different, non-standardized formats [3] [1].

Why is my machine learning model performing poorly on data from a new sampling season? This is a common issue related to individual and environmental variability. Machine learning models trained on data from one set of individuals or one season may not generalize well to new data due to natural variations in animal behavior, movement mechanics, and environmental conditions [4]. To fix this, ensure your training datasets incorporate data from multiple individuals and seasons to capture this inherent variability. Using an unsupervised learning approach to first identify behavioral clusters can help create more robust training labels for subsequent supervised model training [4].

How can I efficiently capture rare behaviors without draining my bio-logger's battery? Instead of continuous recording, use an AI-on-Animals (AIoA) approach. Program your bio-logger to use low-cost sensors (like an accelerometer) to run a simple machine learning model in real-time to detect target behaviors. The logger then conditionally activates high-cost sensors (like a video camera) only during these predicted events, drastically conserving battery [2].

| Strategy | Key Mechanism | Documented Improvement |

|---|---|---|

| AIoA (AI on Animals) | Uses low-power sensors (e.g., accelerometer) to trigger high-power sensors (e.g., video) only during target behaviors [2]. | 15x higher precision in capturing target behaviors compared to periodic sampling [2]. |

| Data Downsampling | Reducing data resolution for specific analyses (e.g., downsampling position data to 1 record per hour for overview visualizations) [5]. | Retains analytical value while significantly reducing dataset size and complexity [5]. |

| Integrated ML Frameworks | Combining unsupervised (e.g., Expectation Maximization) and supervised (e.g., Random Forest) methods to account for individual variability [4]. | Achieved >80% agreement in behavioral classification and more reliable energy expenditure estimates [4]. |

My data formats are inconsistent across devices. How can I make them interoperable?

Adopt standardized data and metadata formats. Inconsistent column names, date formats, and file structures are a major hurdle. Use platforms like the Biologging intelligent Platform (BiP) or tools like the movepub R package, which help transform raw data into standardized formats like Darwin Core for publication to global databases such as GBIF and OBIS [5] [1]. This involves defining consistent column headers, using ISO-standard date formats, and packaging data with comprehensive metadata.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inability to process data in real-time or onboard the animal-borne tag.

- Symptoms: Target behaviors are missed because the logger's memory is full or the battery is depleted before the observation period ends.

- Solution: Implement lightweight, onboard machine learning for sensor triggering.

- Protocol:

- Sensor Selection: Use a low-power sensor like a tri-axial accelerometer as the primary input for behavior detection [2].

- Model Training: Prior to deployment, train a compact machine learning classifier (e.g., a decision tree or random forest) on existing accelerometer data to recognize the target behavior [2] [4].

- Onboard Logic: Program the bio-logger's firmware to run the trained model in real-time on the incoming accelerometer data.

- Conditional Triggering: Define a rule that only powers up the high-cost sensor (e.g., video camera) when the model predicts the target behavior with high confidence. This can extend runtime from 2 hours of continuous video to over 20 hours of targeted recording [2].

Problem: Low accuracy when scaling behavioral predictions to new individuals.

- Symptoms: A model that performed well on the initial training group has low precision/recall when applied to data from new animals or the same animals in a different season.

- Solution: Integrate unsupervised and supervised learning to capture population-level variability.

- Protocol:

- Unsupervised Clustering: Apply an unsupervised clustering algorithm like Expectation Maximization (EM) to a large, unlabeled dataset from multiple individuals. This identifies the natural behavioral clusters without prior assumptions [4].

- Cluster Labeling: Manually interpret and label these automated clusters based on ground-truth observations (e.g., synchronized video) or known sensor data patterns [4].

- Supervised Training: Use these validated clusters as labeled data to train a supervised model, such as a Random Forest. Ensure the training data includes examples from many different individuals [4].

- Prediction & Validation: Use the trained Random Forest to predict behaviors on new, unseen data. Always validate a subset of the predictions against a independent ground-truth source to quantify performance [4].

The table below summarizes the core "Three V" dimensions of large bio-logging datasets, with examples from recent research.

| Dimension | Description | Quantitative Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Volume | The sheer quantity of data generated, often leading to "big data" challenges [4]. | Movebank: 7.5 billion location points & 7.4 billion other sensor records [1]. |

| Velocity | The speed at which data is generated and requires processing. | High-resolution sensors can generate 100s of data points per second, per individual [3]. AIoA systems process this in real-time to trigger cameras [2]. |

| Variety | The diversity of data types and formats from multiple sensors and sources. | Includes GPS, accelerometry, magnetometry, video, depth, salinity, etc. [3] [1]. A single deployment can yield data on location, behavior, and environment [5]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents & Platforms

The following table lists key software solutions and platforms essential for managing and analyzing large bio-logging datasets.

| Tool / Platform | Function | Relevance to Large Datasets |

|---|---|---|

| Movebank | A global database for animal tracking data [1]. | Hosts billions of data points; a primary source for data discovery and archiving [5] [1]. |

| Biologging intelligent Platform (BiP) | An integrated platform for sharing, visualizing, and analyzing biologging data [1]. | Standardizes diverse data formats and metadata, enabling interdisciplinary research and OLAP tools for environmental data calculation [1]. |

movepub R package |

A software tool for automating the transformation of bio-logging data [5]. | Converts complex sensor data from systems like Movebank into the standardized Darwin Core format for publication [5]. |

| Random Forest | A supervised machine learning algorithm for classification [4]. | Used to automatically classify animal behaviors from accelerometer and other sensor data across large, multi-individual datasets [4]. |

| Expectation Maximization | An unsupervised machine learning algorithm for clustering [4]. | Used to identify hidden behavioral states in large, unlabeled datasets before supervised model training [4]. |

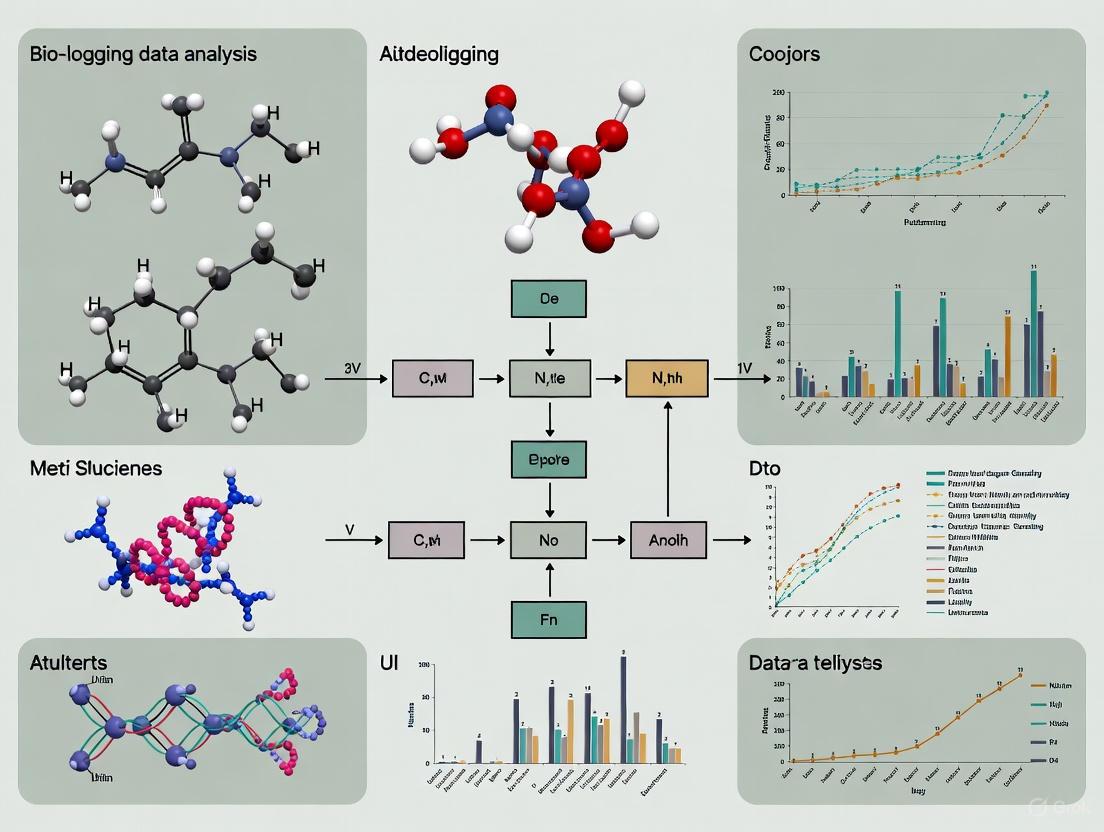

Experimental Data Workflow

The diagram below outlines a standardized workflow for processing large bio-logging datasets, from collection to final analysis, integrating the tools and methods discussed.

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ: What are common challenges when applying machine learning to large bio-logging datasets?

Answer: A primary challenge is individual variability in behavioral signals across different subjects and sampling seasons. When training machine learning models, this variability can reduce predictive performance if not properly accounted for. Studies on penguin accelerometer data show that considering this variability during model training can achieve >80% agreement in behavioral classifications. However, behaviors with similar signal patterns can still be confused, leading to less accurate estimates of behavior and energy expenditure when scaling predictions [4].

FAQ: How can I manage a dataset that is too large to load into memory?

Answer: For datasets that fit on disk but not in memory (e.g., a 200GB file), several strategies exist [6]:

- Process Data in Chunks: Read and process the file sequentially in manageable segments (chunks). Ensure each chunk is representative of the whole dataset.

- Use Appropriate Hardware: Store data on a local NVMe SSD, which can be ~50 times faster than a normal hard drive for such operations, reducing I/O bottlenecks.

- Leverage Database Systems: Load data into a database (e.g., SQL) engineered for efficient querying of large datasets, though this may require more disk space.

- Optimize Code: Use stream readers to process data line-by-line and avoid nested loops or inefficient parsing functions that create memory bottlenecks.

FAQ: My analysis platform is slow when joining large tables. How can I improve performance?

Answer: For platforms like Sigma, which work on top of data warehouses, performance with large datasets can be optimized by [7]:

- Materialization: Perform expensive operations like joins and aggregations upfront, saving the result as a single, pre-computed table that is periodically refreshed.

- Filter Early: Apply filters to reduce both row and column counts as early as possible in the analytical workflow. Use relative date filters to automatically maintain this focus.

- Link Tables Instead of Full Joins: Use key-based linking to avoid joining all columns from a secondary table initially. Users can pull in specific columns later as needed.

FAQ: What are the key considerations for integrating unsupervised and supervised machine learning approaches?

Answer: Integrating these approaches can be a robust strategy [4]:

- Unsupervised Learning (e.g., Expectation Maximization): Useful when validation data is absent and can detect unknown behaviors. A downside is that it requires manual labeling of the identified classes, which does not scale well with large data volumes.

- Supervised Learning (e.g., Random Forest): Effective and fast for predicting known behaviors on novel data, but is limited by the scope and quality of the pre-labeled training dataset.

- Integrated Workflow: Use an unsupervised algorithm to first identify and label behavioral classes from a subset of your data. Then, use these labels to train a supervised model, which can automatically classify behaviors in the remaining or future datasets. This workflow incorporates inherent individual variability into the model.

The table below summarizes quantitative details and purposes of key data sources used in bio-logging and related human studies.

Table 1: Key Data Sources and Sensor Specifications

| Data Source | Common Sampling Rate | Key Measured Variables/Outputs | Primary Research Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accelerometer | 50-100 Hz [8] [9] | Vectorial Dynamic Body Acceleration (VeDBA), body pitch, roll, dynamic acceleration [4] | Classification of behavior (e.g., hunting, walking, swimming) and estimation of energy expenditure [10] [4] |

| GPS | 1 Hz [9] | Latitude, Longitude, Timestamp | Mapping movement paths and linking location to environmental exposures [10] [9] |

| Magnetometer | 50 Hz [8] | Direction and strength of magnetic fields | Determining heading and orientation [8] |

| Gyroscope | 100 Hz [8] | Angular velocity and rotation | Measuring detailed body orientation and turn rate [8] |

| Microphone | 44,100 Hz [8] | Audio amplitude and frequency data | Contextual environmental sensing and activity recognition [8] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item / Tool | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Tri-axial Accelerometer | Captures high-resolution acceleration in three dimensions (surge, sway, heave) to infer behavior and energy expenditure [4]. |

| Animal-borne Bio-logging Tag | A device that integrates multiple sensors (e.g., GPS, accelerometer, magnetometer) and is attached to an animal to collect data in its natural environment [4]. |

| MoveApps Platform | A no-code, serverless analysis platform for building, customizing, and sharing analytical workflows for animal tracking data as part of the Movebank ecosystem [11]. |

| SenseDoc Device | A multi-sensor device used in human studies to concurrently record GPS location and accelerometry data for analyzing physical activity in built environments [9]. |

| Random Forest | A supervised machine learning algorithm used to automatically classify behaviors from pre-labeled accelerometer and other sensor data [4]. |

| Data Materialization | An analytical technique that pre-computes and stores the results of complex operations (like joins) as a single table to drastically improve query performance on large datasets [7]. |

Experimental Protocols and Workflow Visualization

Protocol: Analyzing Built Environments and Physical Activity using GPS and Accelerometry

- Data Collection: Participants wear a device (e.g., SenseDoc) that concurrently records GPS location (e.g., at 1Hz) and tri-axial accelerometry (e.g., at 50Hz) over a specified period (e.g., 1-10 days).

- Data Processing:

- Physical Activity: Raw accelerometer data is converted to activity counts. Cut-points (e.g., Troiano) are applied to classify each minute into sedentary, light, moderate, or vigorous activity.

- Location Data: GPS points are aggregated to a relevant temporal unit (e.g., minute-level median location) and mapped to environmental characteristics.

- Environmental Exposure: Built environment variables (e.g., population density, street density, land use mix, greenness, walkability index) are calculated within a buffer (e.g., 50 meters) around each GPS point.

- Data Integration & Analysis: Physical activity outcomes are joined with environmental exposures based on location and time. Statistical models (e.g., generalized linear mixed models) are used to examine associations, adjusting for demographic and temporal covariates.

Protocol: A Combined ML Approach for Behavioral Classification in Bio-logging

Methodology [4]:

- Data Preparation: Collect accelerometer data across multiple individuals and seasons. Calculate variables like VeDBA, pitch, and standard deviation of raw acceleration over short windows.

- Unsupervised Classification: Apply an unsupervised machine learning algorithm (e.g., Expectation Maximization) to the data from a subset of individuals or trips to identify distinct behavioral classes without prior labels.

- Behavioral Labeling: Manually interpret and label the classes identified by the unsupervised model (e.g., "descend," "swim/cruise," "walking") based on the signal characteristics and complementary data (e.g., depth).

- Supervised Model Training: Use the now-labeled data from step 3 as a training set to teach a supervised algorithm (e.g., Random Forest) to recognize the behaviors.

- Prediction and Scaling: Apply the trained supervised model to classify behaviors in the remaining, larger dataset or in data from new individuals.

Data Analysis Workflow for Bio-logging

This technical support center is designed to assist researchers in navigating the complexities of the bio-logging data pipeline. Handling large, complex datasets from animal-borne sensors presents unique challenges in data collection, processing, and preservation. The following guides and FAQs provide concrete solutions to common technical issues, framed within the broader thesis of advancing ecological research and conservation through robust data management.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Data Collection & Sensor Management

Q: My bio-logging tags are collecting vast amounts of data, but I'm struggling with storage limitations and determining what sensor combinations are most effective. What strategies can I employ?

A: This is a common challenge in bio-logging research. Consider these approaches:

- Multi-sensor Optimization: Follow the Integrated Bio-logging Framework (IBF) to match sensors to your specific biological questions, avoiding unnecessary data collection [3]. The table below summarizes sensor selection guidance:

| Sensor Type | Examples | Primary Application | Common Issues & Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Location | GPS, Argos, Acoustic tags | Space use, migration patterns, home range | Issue: Fix failures under canopy or in deep water [3]. Solution: Combine with dead-reckoning using accelerometers and magnetometers [3]. |

| Intrinsic | Accelerometer, Gyroscope, Magnetometer | Behaviour identification, energy expenditure, 3D path reconstruction [3] | Issue: High data volume [12]. Solution: Use data compression or on-board processing to summarize data [12]. |

| Environmental | Temperature, Salinity, Depth sensors | Habitat use, environmental niche modeling [3] | Issue: Data not linked to animal behaviour. Solution: Deploy in multi-sensor tags with accelerometers for behavioural context [3]. |

| Video | Animal-borne cameras | Direct observation of behaviour and habitat [13] | Issue: Very high data volume, short battery life. Solution: Programmable recording triggers (e.g., based on accelerometer data) to capture specific events [13]. |

- Data Volume Management: For sensors like accelerometers that generate high-frequency data (e.g., 20-40 Hz), you can explore tags with on-board processing capabilities to pre-analyse data and discard erroneous records or transmit summaries [12].

Q: The dead-reckoned tracks I've calculated from accelerometer and magnetometer data are accumulating significant positional errors over time. How can I improve accuracy?

A: Dead-reckoning is powerful but prone to error accumulation. This methodology relies on integrating measurements of heading and speed over time [13].

- Improve Speed Estimates: Instead of assuming a constant speed, use a calibrated speed sensor (e.g., a turbine or paddle wheel) if possible. Alternatively, Dynamic Body Acceleration (DBA) can be a proxy for speed in some terrestrial animals [3].

- Incorporate Ground-Truthing: Use periodic, high-quality GPS fixes (e.g., using Fastloc GPS) to correct the dead-reckoned track [3]. These "anchor points" reset the accumulating error.

- Sensor Calibration: Calibrate magnetometers and accelerometers for sensor bias (e.g., in a lab setting or during periods of known animal rest) to minimize drift at the source [3].

- Data Fusion: Use state-space models to statistically integrate the dead-reckoned path with other available location data, which helps to produce a more accurate and realistic track [12].

Data Processing & Analysis

Q: I have thousands of hours of accelerometer data. What is the most effective way to classify animal behaviors from this data?

A: Machine learning (ML) is the standard approach. The key is choosing the right method and ensuring high-quality training data.

Recommended Workflow:

- Create an Ethogram: Define a clear, discrete inventory of behaviors you wish to classify [14].

- Ground-Truthing: Collect a subset of data where the behavior is known (e.g., from simultaneous video recording) [14].

- Model Selection:

- For high performance: Use deep neural networks (e.g., convolutional or recurrent neural networks), which have been shown to outperform classical methods across diverse species [14]. The V-net architecture, for example, has been successfully applied to sea turtle data with high accuracy [15].

- For smaller datasets or rapid prototyping: Classical methods like Random Forests trained on hand-crafted features (e.g., windowed statistics like mean, variance, and FFT coefficients) can still be effective [14].

- Leverage Transfer Learning: If you have a small annotated dataset, use a model pre-trained with self-supervised learning on a large, generic dataset (e.g., from human accelerometers). This can significantly boost performance with limited labels [14].

Benchmarking: Utilize publicly available benchmarks like the Bio-logger Ethogram Benchmark (BEBE) to compare the performance of your chosen ML techniques against standard methods [14].

Q: How can I efficiently visualize and explore large, multi-dimensional bio-logging datasets to generate hypotheses and spot anomalies?

A: Advanced visualization is key to understanding complex bio-logging data.

- Multi-dimensional Visualizations: Use software tools that can synchronize and visualize multiple data streams (e.g., depth, acceleration, GPS track, video) on a unified timeline [3].

- Custom Software: Tools like the Marine Animal Visualization and Analysis software (

MamVisAD) are designed specifically for handling the large data volumes from tags like the "daily diary," which can record over 650 million data points per deployment [12]. - Integrated Frameworks: Platforms like

Framework 4can be used to visualize dead-reckoned tracks derived from sensor data against satellite imagery, providing spatial context to the animal's movement [13].

Data Sharing & Archiving

Q: I want to archive my bio-logging data in a public repository to satisfy funder mandates and enable collaboration, but I'm concerned about data standards and interoperability. What should I do?

A: Adopting community standards is crucial for making data FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable).

- Use Standardized Templates: Follow frameworks like the one provided by the Ocean Tracking Network's biologging standardization repository on GitHub. This provides three key templates [16]:

- Device Metadata: Captures all information about the bio-logging instrument.

- Deployment Metadata: Details the attachment of the device to the animal.

- Input Data: Describes the bio-logging data collected from one deployment.

- Adopt Controlled Vocabularies: For biological terms, use fields from the Darwin Core (DwC) standard. For sensor-based information, use the Sensor Model Language (SensorML). For other fields, the Climate and Forecast (CF) vocabularies are recommended [16].

- Select a Compliant Repository: Deposit your standardized data in public repositories that support these standards, such as the Seabird Tracking Database or Movebank [17]. This ensures long-term preservation and access.

Experimental Protocols for Bio-Logging Research

Protocol 1: Conducting an Ecological Survey Using Animal-Borne Video

This protocol uses animal-borne cameras to collect ancillary data on habitat and species communities [13].

- Tag Deployment: Deploy a camera tag (e.g., CATS cam) on a focal species using a species-appropriate, non-invasive attachment method (e.g., fin clamp for sharks, suction cups for marine mammals). Permits are essential [13].

- Data Synchronization: Synchronize video footage with other sensor data (e.g., depth, acceleration) by matching a clear event across all streams, such as the moment the tag enters the water [13].

- Video Analysis & Transect Definition:

- Import video into analysis software.

- Define virtual transects based on the animal's path. Assume a constant cruising speed (e.g., 1 m/s) to convert time into distance, or use speed from sensors if available [13].

- For kelp forest surveys, estimate kelp density by counting individuals within a defined frame over set distances (e.g., 50m x 1m transects) [13].

- For benthic cover on reefs, use point-intercept methods at regular intervals (e.g., every meter) to classify the substrate [13].

- Data Integration: Use dead-reckoning or other methods to generate a pseudo-track of the animal's movement. Overlay this track on a satellite image (e.g., in Google Earth) to georeference observations of key species or habitats [13].

Protocol 2: Implementing a Deep Learning Model for Behavior Classification

This protocol outlines the steps to train a deep neural network for automating behavior classification from sensor data [14] [15].

- Data Preparation:

- Gather a labeled dataset from multi-sensor tags (e.g., accelerometer, gyroscope, magnetometer).

- Synchronize sensor data with video recordings to create ground-truthed behavioral labels.

- Segment the synchronized sensor data into fixed-length windows.

- Model Selection & Training:

- Select a model architecture suitable for time-series data, such as a Fully Convolutional Network (e.g., V-net) or a Recurrent Neural Network (e.g., LSTM).

- Divide your data into training, validation, and test sets.

- Train the model on the training set, using the validation set to tune hyperparameters and avoid overfitting.

- Model Evaluation:

- Use the held-out test set to evaluate the model's final performance. Report standard metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and Area Under the Curve (AUC).

- Analyze the confusion matrix to identify which behaviors are most often confused.

- Deployment:

- The trained model can be used to classify behaviors in vast, unlabeled datasets.

- For long-term deployments, explore the possibility of implementing the lightweight model directly on future satellite-relay data tags to transmit behavioral summaries in near-real-time, without needing to recover the tag [15].

Data Pipeline Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the complete bio-logging data pipeline, from collection to final application, highlighting key steps and potential integration points for troubleshooting.

Bio-logging Data Pipeline Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The following table details key resources and tools essential for managing the bio-logging data pipeline effectively.

| Category | Item / Tool | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Data Standards | Darwin Core (DwC) [16] | A standardized framework for sharing biological data, used for terms like species identification and life stage. |

| SensorML [16] | An XML-based language for describing sensors and measurement processes, critical for sensor metadata. | |

| CF Vocabularies [16] | Controlled vocabularies for climate and forecast data, often used for environmental variables. | |

| Software & Platforms | Movebank [17] | A global platform for managing, sharing, and analyzing animal tracking data. |

| Framework 4 [13] | Software used for calculating dead-reckoned tracks from accelerometer and magnetometer data. | |

| BEBE Benchmark [14] | The Bio-logger Ethogram Benchmark provides datasets and code to compare machine learning models for behavior classification. | |

| Analytical Methods | State-Space Models [12] | Statistical models that account for observation error and infer hidden behavioral states from movement data. |

| Dead-Reckoning [3] | A technique to reconstruct fine-scale 2D or 3D animal movements using speed, heading, and depth data. | |

| Overall Dynamic Body Acceleration (ODBA) [12] | A metric derived from accelerometry used as a proxy for energy expenditure. | |

| Community Resources | International Bio-Logging Society (IBLS) [17] | A coordinating body that fosters collaboration and develops best practices, including data standards. |

| Ocean Tracking Network (OTN) [16] | A global research network that provides data management infrastructure and standardization frameworks. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs for Bio-logging Data Analysis

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My machine learning model performs well on data from one individual but poorly on another. What is the cause? This is a classic sign of individual variability [18]. Behaviors can have unique signatures in acceleration data across different individuals due to factors like body size, movement mechanics, or environmental conditions. When a model is trained on a limited subset of individuals, it may not generalize well to new, unseen individuals. To address this, ensure your training dataset incorporates data from a diverse range of individuals and sampling periods [18].

Q2: What are the primary constraints when designing a storage solution for a bio-logger? The design of a bio-logger involves a fundamental trade-off between size/weight, battery life, and memory size [19] [20]. The device must be small and lightweight to minimize impact on the animal, which directly limits battery capacity and available storage. This necessitates highly efficient data management strategies to maximize the amount of data that can be collected within these strict power and memory constraints [20].

Q3: Why is there a community push for standardizing bio-logging data? Standardizing data through common vocabularies and formats enables data integration and preservation [21]. Heterogeneous data from different projects and species can be aggregated into large-scale collections, creating powerful digital archives of animal life. This facilitates broader ecological research, helps mitigate biodiversity threats, and ensures the long-term value and accessibility of collected data [21].

Q4: How can I optimize the memory structure of a bio-logger for time-series data? Using a traditional file system can be inefficient and prone to corruption. A more robust method involves using a custom memory structure with inline, fixed-length headers and data records [20]. This approach reduces overhead and allows for data recovery even if the memory is partially corrupted. Efficient timestamping strategies, such as combining absolute and relative time records, can also significantly save memory [20].

Troubleshooting Guide: Machine Learning Performance

Problem: Low accuracy when predicting behaviors for new individuals. This indicates your model is failing to generalize due to inter-individual variability [18].

- Step 1: Diagnose the Issue. Compare the model's performance per individual. If accuracy is high for individuals in the training set but low for others, individual variability is likely the cause.

- Step 2: Revise Training Data. The solution is to incorporate more variability into your model. Expand your training set to include data from multiple individuals and across different sampling seasons [18].

- Step 3: Consider a Hybrid Approach. If labeled data is scarce, use an unsupervised learning method (like Expectation Maximisation) to detect behavioral classes across a diverse dataset. Then, use these classifications to train a supervised model (like Random Forest) [18]. This workflow integrates inherent variability from the start.

- Step 4: Evaluate Energetic Consequences. Assess how misclassifications impact downstream analyses like estimates of energy expenditure (e.g., Daily Energy Expenditure). Some behavioral confusions may have minimal effect, while others can lead to significant inaccuracies [18].

Performance Metrics for Behavioral Classification

The following table summarizes the agreement in behavior classification between unsupervised (Expectation Maximisation) and supervised (Random Forest) machine learning approaches when individual variability is accounted for [18].

| Performance Metric | Value | Context and Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Agreement | > 80% | High agreement between methods when behavioral variability is included in training [18]. |

| Outlier Agreement | < 70% | Occurs for behaviors with similar signal patterns, leading to confusion [18]. |

| Impact on Energy Expenditure | Minimal difference | Overall DEE estimates were robust despite some behavioral misclassification [18]. |

Experimental Protocol: Integrating ML Approaches to Account for Individual Variability

This protocol outlines the methodology for classifying animal behavior from accelerometer data while incorporating individual variability [18].

1. Objective: To reliably classify behaviors in bio-logging data by integrating unsupervised and supervised machine learning to account for individual variability and ensure robust energy expenditure estimates.

2. Materials and Equipment:

- Bio-loggers: Tri-axial accelerometer tags deployed on study animals (e.g., penguins) [18].

- Data Processing Software: Python or MATLAB for data analysis [20].

- Computational Resources: Standard computer workstations capable of handling large datasets.

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Data Preparation. Collect raw acceleration data. Calculate variables such as:

- Vectorial Dynamic Body Acceleration (VeDBA)

- Body pitch and roll

- Standard deviation of raw heave acceleration

- Change in depth (for diving species) [18].

- Step 2: Unsupervised Classification (Expectation Maximisation). Run an EM algorithm on the processed data from all individuals to identify hidden behavioral classes without pre-defined labels. This step detects the natural structure and variability in the data [18].

- Step 3: Manual Labeling. Manually label the behavioral classes identified by the EM algorithm using simultaneous video validation or expert knowledge [18].

- Step 4: Supervised Classification (Random Forest). Use the manually labeled data from Step 3 to train a Random Forest model. The training set should be a random selection of data that includes the variability found in Step 2 [18].

- Step 5: Prediction and Validation. Use the trained Random Forest model to predict behaviors in the remaining, unlabeled data. Assess the agreement between the behaviors classified by the EM algorithm and the Random Forest model [18].

- Step 6: Calculate Energy Expenditure. Group the classified behaviors and calculate activity-specific Dynamic Body Acceleration (DBA) as a proxy for energy expenditure. Compare the Daily Energy Expenditure (DEE) estimates derived from both the EM and Random Forest classifications to ensure consistency [18].

4. Analysis:

- Quantify the percentage agreement between the two machine learning approaches [18].

- Identify which behaviors are most commonly confused.

- Statistically compare the final DEE estimates from both methods to ensure differences are not significant [18].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key hardware and computational "reagents" essential for bio-logging research.

| Item Name | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Tri-axial Accelerometer Tag | The primary data collection device; records high-resolution acceleration in three dimensions (surge, sway, heave) to infer behavior and energy expenditure [18]. |

| NAND Flash Memory Module | A low-power, non-volatile storage solution for bio-loggers, preferred over micro-SD cards for its power efficiency and reliability in embedded systems [20]. |

| Custom Data Parser Script | A script (e.g., in Python or MATLAB) to read and interpret the custom memory structure and timestamping scheme from the raw memory bytes of the retrieved bio-logger [20]. |

| Movebank Database | A centralized platform for storing, managing, and sharing animal tracking data; supports data preservation and collaborative science [21]. |

| Expectation Maximisation (EM) | An unsupervised machine learning algorithm used to identify hidden behavioral states or classes in complex accelerometer data without pre-labeled examples [18]. |

| Random Forest | A supervised machine learning algorithm used to classify known behaviors rapidly and reliably; trained on data labeled via the unsupervised approach or direct observation [18]. |

Data Management Platforms for Bio-Logging Research

The explosion of data from bio-logging—the use of animal-borne electronic tags—presents a paradigm-changing opportunity for ecological research and conservation [3] [21]. This field generates vast, complex datasets comprising movements, behaviors, physiology, and environmental conditions, creating pressing challenges for data storage, integration, and analysis [3] [22]. Establishing robust data management platforms is no longer optional but is essential for preserving the value of this data and enabling future discoveries.

Platforms like Movebank have emerged as core infrastructures to address these challenges. Movebank is an online database and research platform designed specifically for animal movement and sensor data, hosted by the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior [23] [24]. Its primary goals include archiving data for future use, enabling scientists to combine datasets from separate studies, and promoting open access to animal movement data while allowing data owners to control access permissions [25] [23].

Table 1: Core Features of the Movebank Data Platform

| Feature Category | Specific Capabilities |

|---|---|

| Data Support | GPS, Argos, bird rings, accelerometers, magnetometers, gyroscopes, light-level geolocators, and other bio-logging sensors [25] [23]. |

| Data Management | Import data from files or set up live feeds from deployed tags; filter data; edit attributes; and manage deployment periods [25] [23]. |

| Data Sharing & Permissions | Data owners control access; options range from private to public; custom terms of use can be enforced [25] [23]. |

| Data Analysis | Visualization tools; integration with R via the move package; annotation of data with environmental variables [23]. |

| Data Archiving | Movebank Data Repository provides formal publication of datasets with a DOI, making them citable and ensuring long-term preservation [23] [24]. |

The need for such platforms is underscored by the reality that a significant portion of bio-logging data has historically remained unpublished and inaccessible [23]. Effective data management requires not just technology but also a cultural shift towards collaborative, multi-disciplinary science and the adoption of standardized practices for data reporting and sharing [3] [21].

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Data Import and Management

Q: I am getting an error message during data import, or my changes won't save. What should I do?

Error messages can stem from several factors. First, check your file formatting to ensure it conforms to Movebank's requirements. Internet connection problems or server issues can sometimes be the cause. For persistent errors, the issue may be cached information in your web browser. Try bypassing or clearing your browser's cache. If the problem continues, contact Movebank support at support@movebank.org and provide a detailed description of how to recreate the problem and the exact text of the error message [25].

Q: Why don't my animal tracks appear on the Tracking Data Map?

If you are logged in and have permission to view tracks but don't see them, it is likely that the event records are linked to Tag IDs but not to Animal IDs. To resolve this, navigate to your study, go to Download > Download reference data to check the current deployment information. You can then add or correct the Animal ID associations using the Deployment Manager or by uploading an updated reference data file [25].

Q: What does the error "the data does not contain the necessary Argos attributes" mean?

This error appears when running Argos data filters if your dataset is missing specific attributes required for the filtering algorithm. Ensure your imported data contains the following columns: the primary and alternate location estimates (Argos lat1, Argos lon1, Argos lat2, Argos lon2), Argos LC (location class), Argos IQ, and Argos nb mes. If these original values are missing from your source data, the filter cannot execute properly [25].

Data Analysis and Access

Q: Can I use Movebank to fulfill data-sharing requirements from my funder or a journal?

Yes. A major goal of Movebank is to help scientists comply with data-sharing policies from funding agencies like the U.S. National Science Foundation and academic journals. The Movebank Data Repository is designed specifically for this purpose, allowing you to formally publish and archive your dataset, which receives a DOI for citation in related articles. You can contact Movebank support for assistance in preparing a data management plan [25].

Q: How can I access and analyze my data directly in R?

You can access Movebank data directly in R using the move package. First, install and load the package (install.packages("move") and library(move)). You must first agree to the study's license terms via the Movebank website. Then, use the getMovebankData() function with your login credentials and the exact study name to load the data as a MoveStack object, which can be converted to a data frame for further analysis [23].

Q: My analysis requires multi-sensor data integration. What is the best approach?

Multi-sensor approaches are a new frontier in bio-logging. An Integrated Bio-logging Framework (IBF) is recommended to optimally match sensors and analytical techniques to specific biological questions. This often requires multi-disciplinary collaboration between ecologists, engineers, and statisticians. For instance, combining accelerometers (for behavior and dynamic movement) with magnetometers (for heading) and pressure sensors (for altitude/depth) allows for 3D movement reconstruction via dead-reckoning, which is invaluable when GPS locations fail [3].

Experimental Protocols for Data Handling

Protocol: Archiving a Geolocator Dataset in Movebank

This protocol outlines the steps for archiving light-level geolocator data, ensuring that all components needed for re-analysis are preserved [24].

1. Study Creation and Setup:

- Log in to Movebank and create a new study. Provide a detailed study name and description.

- Define the study's access permissions for the public and add collaborators if needed.

- Set license terms that users must accept to download the data.

2. Importing Reference Data:

- Before importing sensor data, upload a reference data table containing deployment information. This links tags to specific animals and defines deployment periods.

- Essential attributes include

animal-id,tag-id,deployment-start, anddeployment-end.

3. Importing Raw Light-Level Recordings:

- Go to

Upload Data > Import Data > Light-level data > Raw light-level data. - Upload your file containing the raw light readings.

- Map the columns in your file to Movebank attributes. You must map:

- A

Tag IDcolumn or assign all rows to a single tag. - The

timestampcolumn, carefully specifying the date-time format. - The

light-levelvalue column.

- A

- Save the file format for future imports.

4. Importing Annotated Twilight Data:

- Go to

Upload Data > Import Data > Light-level data > Twilight data. - Upload your file of selected twilights (e.g., from

TAGSorTwGeossoftware). - Map the essential columns:

timestampfor the twilight event.geolocator riseto indicate sunrise (TRUE) or sunset (FALSE).- Optional but recommended:

twilight excludedandtwilight insertedto document your editing steps.

5. Importing Location Estimates:

- Go to

Upload Data > Import Data > Location data. - Upload the file containing your final location estimates.

- Map the

timestamp,location-lat, andlocation-longcolumns.

6. Data Publication (Optional but Recommended):

- Once your analysis is complete and a related manuscript is in review, submit your study to the Movebank Data Repository.

- The dataset will be reviewed and, upon acceptance, assigned a DOI and a persistent citation, formally archiving it for the long term [24].

Protocol: Transforming GPS Tracking Data for Biodiversity Archives

To contribute animal tracking data to global biodiversity platforms like the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF), it must be transformed into the Darwin Core (DwC) standard. The following protocol uses the R package movepub [26].

1. Data Preparation:

- Ensure your GPS tracking data is an archive-quality study in Movebank, preferably with a DOI.

- Flag and exclude low-quality or questionable records as outliers.

- Exclude data from animals that were experimentally manipulated in ways that affect their typical behavior.

- If necessary, reduce the precision of locations for sensitive species to mitigate potential threats.

2. Data Transformation:

- Use the

movepubR package to transform your Movebank-format data into a Darwin Core Archive. - The transformation involves mapping Movebank attributes to corresponding DwC terms (e.g.,

individual-taxon-canonical-namefor species,event-datefor timestamp). - A key step in this process is reducing the data to hourly positions per animal to decrease data volume while retaining sufficient resolution for biodiversity modeling.

3. Publication and Attribution:

- Publish the resulting Darwin Core Archive to GBIF via a registered organization.

- Choose a Creative Commons license to define terms of use and require attribution.

- The preferred citation should link back to the original Movebank-format dataset to better track its use and impact [26].

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Data Management and Integration Workflow

Integrated Bio-logging Framework (IBF)

This diagram visualizes the feedback loops essential for optimizing bio-logging study design, from question formulation to data analysis, highlighting the need for multi-disciplinary collaboration [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Tools for Managing Bio-logging Data

| Tool or Resource | Type | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Movebank Platform | Online Database | Core infrastructure for storing, managing, sharing, and analyzing animal movement and sensor data [23]. |

R move package |

Software Package | Enables direct access to, and analysis of, Movebank data within the R environment, facilitating reproducible research [23]. |

| Darwin Core Standard | Data Standard | A widely adopted schema for publishing and integrating biodiversity data, enabling tracking data to contribute to platforms like GBIF [26]. |

R movepub package |

Software Package | Provides functions to transform GPS tracking data from Movebank format into the Darwin Core standard for publication [26]. |

| Integrated Bio-logging Framework (IBF) | Conceptual Framework | A structured approach to guide the selection of appropriate sensors and analytical methods for specific biological questions, emphasizing collaboration [3]. |

| Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) | Sensor | A combination of sensors (e.g., accelerometer, magnetometer, gyroscope) that allows for detailed behavior identification and 3D path reconstruction via dead-reckoning [3]. |

Advanced Analytical Techniques for Complex Behavioral and Environmental Data

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues & Solutions

FAQ 1: How do I choose between an unsupervised (EM) and a supervised (Random Forest) approach for my bio-logging data?

| Consideration | Expectation-Maximization (EM) | Random Forest |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Use Case | Ideal when no pre-labeled data exists or for discovering unknown behaviors [27]. | Best for predicting known, pre-defined behaviors on large, novel datasets [27]. |

| Data Requirements | Does not require labeled training data; discovers patterns from raw data [27]. | Requires a pre-labeled dataset for training the model [27]. |

| Output | Identifies behavioral classes that must be manually interpreted and labeled by a researcher [27]. | Provides automatic predictions of behavioral labels for new data [27]. |

| Strengths | Can detect novel, unanticipated behaviors without prior bias [27]. | Fast, reliable for classifying known behaviors, and handles high-dimensional data well [27] [28]. |

| Common Challenges | Manual labeling of discovered classes does not scale well with large datasets [27]. | Limited to the behaviors represented in the training data; may not identify new behavioral states [27]. |

Recommended Solution: For a robust workflow, consider an integrated approach. Use the unsupervised EM algorithm to detect and label behavioral classes on a subset of your data. These labeled data can then be used to train a Random Forest model, which can automatically classify behaviors across the entire dataset, efficiently handling large data volumes [27].

FAQ 2: My model performance is poor. How can I account for individual variability in behavior?

Individual variability in movement mechanics and environmental contexts is a major challenge that can reduce model accuracy [27].

Recommended Solution:

- Inclusive Training Data: Ensure your training dataset includes data from multiple individuals across different sampling seasons or environmental conditions. When training the Random Forest model, randomly sample data from across the entire population and all relevant conditions, rather than from a single individual, to build a model that generalizes better [27].

- Performance Evaluation: Assess the agreement between classifications from an unsupervised method (like EM) and your supervised model. High agreement (>80%) suggests individual variability is being adequately captured, while lower agreement (<70%) on specific behaviors indicates a need for more representative training data for those actions [27].

FAQ 3: What are the consequences of misclassification on downstream analyses like energy expenditure?

Misclassifying behaviors can lead to significant errors in derived ecological metrics, such as Daily Energy Expenditure (DEE), which is often calculated using behavior-specific proxies like Dynamic Body Acceleration (DBA) [27].

Recommended Solution:

- Quantify Impact: Compare DEE estimates calculated from behavioral classifications generated by both EM and Random Forest. High agreement in behavioral predictions typically results in minimal differences in DEE, validating your approach [27].

- Focus on Problem Behaviors: Pay special attention to behaviors with high signal similarity (e.g., different swimming modes). Confusion between these can disproportionately affect energy estimates. Manually review and refine the classification rules or training labels for these specific activities [27].

FAQ 4: How can I optimize my bio-logger's battery life when collecting high-cost sensor data (e.g., video)?

Continuously recording from resource-intensive sensors like video cameras quickly depletes battery capacity [29].

Recommended Solution: Implement an AI-on-Animals (AIoA) strategy. Use a low-cost sensor, like an accelerometer, to run a simple machine learning model directly on the bio-logger. This model detects target behaviors in real-time and triggers the high-cost video camera only during these periods of interest [29].

AI-Assisted Bio-Logging Workflow

This method has been shown to increase runtime by up to 10 times (e.g., from 2 hours to 20 hours) and can improve the precision of capturing target videos by 15 times compared to periodic sampling [29].

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Methodology: Integrated EM and Random Forest Workflow

This protocol outlines the steps for using an unsupervised algorithm to create labels for training a supervised model, as applied to penguin accelerometer data [27].

1. Data Preparation and Preprocessing:

- Sensor Data: Collect raw tri-axial acceleration data. From this, calculate variables such as:

- Vectorial Dynamic Body Acceleration (VeDBA)

- Body pitch and roll

- Standard deviation of raw heave acceleration over 2-second and 10-second windows

- Change in depth (for diving species) [27].

- Data Subsetting: Segment the data based on broad context (e.g., diving vs. on land) to improve model performance, as different behaviors dominate in different contexts [27].

2. Unsupervised Behavioral Clustering with Expectation-Maximization (EM):

- Algorithm Application: Apply the EM algorithm to the preprocessed dataset from the previous step. The EM algorithm iterates between two steps:

- E-step (Expectation): Estimates the probability that each data point belongs to each potential latent (hidden) behavioral class.

- M-step (Maximization): Adjusts the model parameters to maximize the likelihood of the data given the class probabilities from the E-step [30].

- Behavioral Labeling: The algorithm will output a set of clusters. Manually interpret and label these clusters into ethogram behaviors (e.g., "descend," "ascend," "hunt," "walking," "standing") by examining the characteristic signal patterns within each cluster [27].

3. Supervised Behavioral Prediction with Random Forest:

- Dataset Creation: Use the labels generated in Step 2 to create a labeled training dataset.

- Model Training: Train a Random Forest classifier. This involves:

- Creating multiple decision trees, each trained on a random subset of the data and features.

- Each tree makes an independent prediction on new data.

- The final behavioral classification is determined by majority voting across all trees in the "forest" [28].

- Prediction and Upscaling: Apply the trained Random Forest model to classify behaviors in the remaining, unlabeled portions of your dataset or in new datasets from the same population [27].

Integrated EM and Random Forest Analysis Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Tool / Solution | Function in Behavioral Analysis |

|---|---|

| Tri-axial Accelerometer | A core sensor in bio-loggers that measures acceleration in three dimensions (surge, sway, heave), providing data on body posture, dynamic movement, and effort, which serve as proxies for behavior and energy expenditure [27] [3]. |

| Integrated Bio-logging Framework (IBF) | A decision-making framework to guide researchers in optimally matching biological questions with appropriate sensor combinations, data visualization, and analytical techniques [3]. |

| Bio-logger Ethogram Benchmark (BEBE) | A public benchmark comprising diverse, labeled bio-logger datasets used to evaluate and compare the performance of different machine learning models for animal behavior classification [14]. |

| AI-assisted Bio-loggers | Next-generation loggers that run lightweight machine learning models on-board. They use low-power sensors to detect behaviors of interest and trigger high-cost sensors (e.g., video) only then, dramatically extending battery life [29]. |

| Dynamic Body Acceleration (DBA) | A common metric derived from accelerometer data used as a proxy for energy expenditure during specific behaviors, allowing for the construction of "energy landscapes" [27]. |

| Phenotypic Screening Platforms (e.g., SmartCube) | Automated, high-throughput systems used in drug discovery that employ computer vision and machine learning to profile the behavioral effects of compounds on rodents, identifying potential psychiatric therapeutics [31] [32]. |

Integrating Unsupervised and Supervised Learning for Robust Predictions

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the main advantages of integrating unsupervised and supervised learning for bio-logging data?

Integrating these approaches leverages their complementary strengths. Unsupervised learning, such as Expectation Maximisation (EM), can identify novel behavioural classes from unlabeled data without prior bias, which is crucial for discovering unknown animal behaviours [18]. Supervised learning, such as Random Forest, then uses these identified classes as labels to train a model that can rapidly and automatically classify new, large-volume datasets [18]. This hybrid method is a viable approach to account for individual variability across animals and sampling seasons, making behavioural predictions more robust and feasible for extensive datasets [18].

FAQ 2: My supervised model performs well on training data but poorly on new individual animals. What is the cause and how can I fix it?

This is a common issue often caused by inter-individual variability in behaviour and movement mechanics, which the model has not learned to generalize [18]. To address this:

- Include More Individuals in Training: Ensure your training dataset incorporates data from a diverse set of individuals, not just one or a few [18]. This helps the model learn the range of natural variation.

- Use Unsupervised Learning for Initial Labeling: First apply an unsupervised method (like EM) to data from multiple individuals. The resulting behavioural classes will inherently reflect some of the variability present. Use these classes to train your supervised model [18].

- Add Feature Statistics: Incorporate individual animal characteristics (e.g., species, size) as features in your model. This has been shown to improve cross-validation accuracy across different individuals [33].

FAQ 3: How can I efficiently capture rare behaviours with resource-intensive sensors (e.g., video cameras) on bio-loggers?

The AI on Animals (AIoA) framework provides a solution. This method uses a low-cost sensor (like an accelerometer) running a machine learning model on-board the bio-logger to detect target behaviours in real-time [34]. The bio-logger then conditionally activates the high-cost sensor (like a video camera) only during these detected periods. This dramatically extends battery life and increases the precision of capturing target behaviours. One study achieved 15 times the precision of periodic sampling for capturing foraging behaviour in seabirds using this method [34].

FAQ 4: What are the consequences of misclassifying behaviours on downstream analyses like energy expenditure?

Misclassification can lead to inaccurate estimates of energy expenditure. Activity-specific Dynamic Body Acceleration (DBA) is a common proxy for energy expenditure [18]. If behaviours are misclassified, the DBA values associated with the incorrect behaviour will be applied, skewing the calculated Daily Energy Expenditure (DEE) [18]. While one study found minimal differences in DEE when individual variability was considered, it also highlighted that misclassification of behaviours with similar acceleration signals can occur, potentially leading to less accurate estimates [18].

FAQ 5: Which supervised learning algorithm is best for classifying behaviours from accelerometer data?

There is no single "best" algorithm, as performance can vary by dataset and species. However, research comparing algorithms on otariid (fur seal and sea lion) accelerometer data found that a Support Vector Machine (SVM) with a polynomial kernel achieved the highest cross-validation accuracy (>70%) for classifying a diverse set of behaviours like resting, grooming, and feeding [33]. The table below summarizes the performance of various tested algorithms. It is always recommended to test and validate several algorithms on your specific data.

Table 1: Performance of Supervised Learning Algorithms on Accelerometer Data from Otariid Pinnipeds [33]

| Algorithm | Reported Cross-Validation Accuracy | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SVM (Polynomial Kernel) | >70% | Achieved the best performance in the study. | |

| SVM (Other Kernels) | Lower than Polynomial Kernel | Four different kernels were tested. | |

| Random Forests | Evaluated | A commonly used and reliable algorithm. | |

| Stochastic Gradient Boosting (GBM) | Evaluated | ||

| Penalised Logistic Regression | Evaluated | Used as a baseline model. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Agreement Between Unsupervised and Supervised Behavioural Classifications

Description: After using an unsupervised method to label data and training a supervised model, the predictions from the supervised model show low agreement (e.g., <70%) with the original unsupervised classifications [18].

Solution Steps:

- Investigate Signal Similarity: Analyse the acceleration signals of the confused behaviours. Low agreement often occurs for behaviours characterized by very similar signal patterns [18]. Manual inspection and refinement of these specific classes may be necessary.

- Check for Overfitting: Ensure your supervised model is not overfitting the training data. Use cross-validation techniques during model training to guarantee it generalizes well to new, unseen data [35].

- Refine Feature Set: Re-evaluate the features (e.g., VeDBA, pitch, standard deviation of heave) you are extracting from the raw data. The initial set may not be discriminative enough for the confused behaviours. Consider feature engineering to create more informative inputs [18] [35].

- Validate with Expert Knowledge: Where possible, use direct observations (e.g., from video recordings) to validate the behaviours that are being confused and adjust your class definitions or training data accordingly [33].

Problem: Handling High-Dimensional, Multi-Omics Data for Integration

Description: While focused on bio-logging, researchers may also need to integrate other heterogeneous data types, such as multi-omics data (genomics, transcriptomics, etc.), which presents challenges in data fusion [36].

Solution Steps:

- Choose a Mixed Integration Strategy: Avoid simple early integration (data concatenation), which can increase dimensionality and bias. Opt for mixed integration strategies that transform each dataset separately before fusion [36].

- Utilize Multiple Kernel Learning (MKL): MKL is a natural framework for integrating heterogeneous data. It represents each omics dataset as a kernel matrix (a similarity measure between samples), then combines these kernels into a meta-kernel for a unified analysis [36].

- Leverage Platform Tools: Use open analysis platforms like MoveApps which are designed to handle complex animal movement data through modular workflows (Apps) [37]. This allows for reproducible and scalable analysis without deep coding expertise.

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: A Hybrid EM and Random Forest Workflow for Behavioural Classification

This protocol is adapted from research on classifying behaviours in penguins [18].

- Data Preparation: Collect raw tri-axial acceleration data. Calculate relevant variables such as Vectorial Dynamic Body Acceleration (VeDBA), body pitch, roll, and standard deviations of raw acceleration over specific time windows (e.g., 2s for heave during dives) [18].

- Unsupervised Labelling (Expectation Maximisation):

- Apply the EM algorithm to the calculated variables to identify latent behavioural classes.

- Manually interpret and label the resulting classes based on the characteristic signal patterns (e.g., "descend," "ascend," "hunt," "resting") [18].

- Training Dataset Creation:

- Use the labels from Step 2 as the ground truth.

- Randomly select data segments from multiple individuals to create a training dataset that captures inter-individual variability [18].

- Supervised Model Training (Random Forest):

- Prediction and Validation:

- Use the trained Random Forest model to predict behaviours on new, unknown data.

- Assess the agreement between the unsupervised and supervised classifications and validate critical behaviours with independent observations if possible [18].

Diagram 1: EM and Random Forest integration workflow.

Protocol 2: On-Board AI for Targeted Video Capture (AIoA)

This protocol is adapted from experiments on seabirds to capture foraging behaviour [34].

- Initial Data Collection: Deploy bio-loggers with both low-cost (accelerometer, GPS) and high-cost (video camera) sensors. Collect continuous data from the low-cost sensors and simultaneously record video for a limited period to create a labelled reference [34].

- Model Training for On-Board Use: Train a machine learning classifier (e.g., using accelerometer features) to detect the target behaviour (e.g., foraging) from the low-cost sensor data. This model must be optimized for low computational power [34].

- Embed Model on Bio-logger: Upload the trained model to the bio-logger's memory.

- Deploy with Conditional Triggering: Deploy the bio-logger with a conditional recording script: the low-cost sensors run continuously, and the embedded AI model analyses this data in real-time. Only when the target behaviour is detected with high confidence is the high-cost video camera activated [34].

- Post-Recovery Analysis: Retrieve the bio-logger and analyse the video clips to verify the target behaviour was captured and assess the precision and recall of the system [34].

Table 2: Performance of AIoA vs. Naive Sampling in Seabird Studies [34]

| Method | Target Behaviour | Precision | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| AIoA (Accelerometer) | Gull Foraging | 0.30 | 15x precision of naive method; target behaviour was only 1.6% of data. |

| Naive Sampling | Gull Foraging | 0.02 | Captured mostly non-target behaviour. |

| AIoA (GPS) | Shearwater Area Restricted Search | 0.59 | Significantly outperformed periodic sampling. |

| Naive Sampling | Shearwater Area Restricted Search | 0.07 | Poor targeting of the behaviour of interest. |

Diagram 2: On-board AI for conditional sensor triggering.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Materials and Tools for Bio-logging Data Analysis

| Item / Solution | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Tri-axial Accelerometer | Core sensor for measuring surge, sway, and heave acceleration, used to infer behaviour and energy expenditure (DBA) [18] [33]. |

| MoveApps Platform | A serverless, no-code platform for building modular analysis workflows (Apps) for animal tracking data, promoting reproducibility and accessibility [37]. |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) | A supervised learning algorithm effective for classifying behavioural states from accelerometry data, particularly with a polynomial kernel [33]. |

| Random Forest | A robust supervised learning algorithm used for classifying behaviours after initial labelling with unsupervised methods [18]. |

| Expectation Maximisation (EM) | An unsupervised learning algorithm used to identify latent behavioural classes from unlabeled acceleration data [18]. |

| Multiple Kernel Learning (MKL) | A framework for integrating heterogeneous data sources (e.g., multi-omics) by combining similarity matrices (kernels), applicable to complex bio-logging data integration [36]. |

| R Software Package | The primary programming environment for movement ecology, hosting a large community and extensive packages for analysing tracking data [37]. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Q: The AI model on the bio-logger is producing inaccurate behavioral classifications. How can we improve performance?

A: Inaccurate classifications often stem from individual animal variability or signal similarity between behaviors. Implement this integrated machine learning workflow to enhance prediction robustness [18].

Experimental Protocol for Model Retraining:

- Data Preparation: Collect raw, high-resolution accelerometer data (surge, sway, heave). Calculate variables like Vectorial Dynamic Body Acceleration (VeDBA), pitch, roll, and standard deviation of raw acceleration over different time windows (e.g., 2s, 10s, 30s) [18].

- Unsupervised Learning (Behavior Discovery):

- Apply an Expectation Maximization (EM) algorithm to the dataset without pre-defined labels. This identifies inherent behavioral classes and helps detect unknown or unexpected behaviors [18].

- Manually label the resulting behavioral classes based on expert observation or video validation. Classes may include "descend," "ascend," "hunt," "swim/cruise," "walking," and "preening" [18].

- Supervised Learning (Behavior Prediction):

- Performance Validation: Assess the agreement between the unsupervised (EM) and supervised (Random Forest) approaches. Target agreement above 80% for reliable classifications. Be aware that behaviors with similar signal patterns (e.g., "swim/cruise" variants) may show lower agreement and require special attention [18].

Diagram: Integrated ML Workflow for Behavioral Classification

Q: Our bio-logging devices are experiencing rapid battery drain. What are the primary causes and solutions?

A: Battery life is critical for field deployments. High energy consumption is frequently caused by excessive data transmission and suboptimal logging configurations [38].

Methodology for Power Consumption Optimization:

- Implement On-Device Intelligence:

- Deploy lightweight AI models on the bio-logger to perform initial data processing and filtering directly on the device [38].

- Configure the device to transmit only summary data or exception events (e.g., detected behaviors of interest) rather than streaming all raw data continuously. This drastically reduces transmission power [38].

- Optimize Data Logging Parameters:

- Evaluate and adjust the sampling resolution (frequency) of sensors. Lower non-essential sampling rates to the minimum required for your study [38].

- Use a structured logging library instead of custom file-writing code. These libraries are optimized for efficiency and can help manage write operations to conserve power [39].

- General Device Troubleshooting: If power issues persist, follow standard procedures: restart the device, ensure the operating system and application firmware are up to date, and as a last resort, uninstall and reinstall the device software [40].

Table: Common Power Issues and Recommended Actions

| Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Rapid battery drain | Continuous high-frequency data transmission | Implement on-board AI for targeted data capture; transmit only processed summaries [38]. |

| Unexpected shutdown | Firmware bug or corrupted software | Restart the device; update to the latest firmware version; reinstall application if needed [40]. |

| Reduced battery capacity over time | Normal battery degradation | Plan for device retrieval and battery replacement according to manufacturer guidelines. |

Q: We are encountering connectivity issues when retrieving data from field-deployed bio-loggers. How can we resolve this?

A: Connectivity problems can prevent access to crucial data. Systematic troubleshooting of network settings is required [40].

Protocol for Network Troubleshooting:

- Basic Device Checks: Perform a force-close and restart of the device application. This clears temporary cache and often resolves minor hiccups [40].

- Network Settings Reset:

- On the device, navigate to Settings > General > Reset.

- Select "Reset Network Settings." This will restore all network configurations to factory defaults and may resolve underlying connectivity conflicts. Note that this will erase saved Wi-Fi networks and VPN settings [40].

- VPN and Interference Check:

- If you use a VPN, disable it completely in the device settings, as VPNs can interfere with stable connections to your data server [40].

- Ensure the device has a strong enough signal to your wireless or cellular network.

Q: The data we are collecting contains inconsistencies and is difficult to analyze computationally. How should we structure our data and metadata?

A: Proper data structure is foundational for analyzing large, complex bio-logging datasets. Adhere to computational data tidiness principles [41].

Experimental Protocol for Data Management:

- File Organization: Leave raw data raw—never modify the original data files. Create a clear folder structure for raw data, cleaned data, scripts, and metadata [41].

- Spreadsheet Structuring for Metadata:

- Place each observation or sample in its own row [41].

- Place all variables (e.g., animalid, deploymentdate, VeDBA, behavior_class) in columns [41].

- Use explanatory column names without spaces. Separate words with underscores (e.g.,

client_sample_id) or use camel case (e.g.,sampleID) [41]. - Do not combine multiple pieces of information in one cell. For example, separate genus and species into distinct columns [41].

- Avoid using color to encode information, as it is not machine-readable [41].

- Create Unique Identifiers: Assign a unique identifier to each sample and deployment. This is critical for correctly associating samples and data files later in the analysis pipeline [41].

- Data Export: Save and archive cleaned data in a text-based, interoperable format like CSV (comma-separated values) [41].

Table: Common Data Structuring Errors and Corrections

| Common Error | Example (Incorrect) | Best Practice (Correct) | Principle |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple variables in one cell | E. coli K12 |

Column 1: E_coliColumn 2: K12 |

Store variables in separate columns [41]. |

| Inconsistent naming | wt, Wild type, wild-type |

wild_type (consistent across all entries) |

Use consistent, explanatory labels [41]. |

| Using color or formatting | Highlighting rows red to indicate errors | Add a new column: data_quality_flag |

Data should be readable by code alone [41]. |

| Missing unique identifiers | Samples named "PenguinA", "PenguinA" | Samples named "ADPE2024001", "ADPE2024002" | Create unique identifiers for all samples [41]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What is the impact of individual animal variability on the predictive performance of AI models, and how can it be managed?

A: Individual variability in movement mechanics is a major source of classification error if not accounted for. It can lead to less accurate estimates of behavior and energy expenditure when models are applied across individuals or seasons [18]. Management requires explicitly including data from multiple individuals and sampling periods in the model training dataset. This allows the supervised learning algorithm to learn the range of natural variation, improving its robustness and accuracy on novel data [18].

Q: How can we ensure our data visualizations and diagrams are accessible?

A: Accessibility in visualization is crucial for clear communication. Adhere to the following rules using the provided color palette:

- Contrast Ratio: Ensure a minimum contrast ratio of 3:1 for meaningful graphics (like chart elements) against adjacent colors and the background [42].

- Color Blindness: Do not rely on color alone to convey information. Use differing lightnesses and textures, and leverage online tools to check that palettes are distinguishable by users with color vision deficiencies [43].

- Intuitive Palettes: For gradients, use light colors for low values and dark colors for high values. For categories, use distinct hues rather than shades of a single color to avoid implying a false ranking [43].

Q: What are the key logging best practices for software managing the bio-logger?

A: Effective logging is essential for troubleshooting deployed devices.

- Use Standard Libraries: Never write logs to files manually. Use established logging libraries (e.g., for Python:

loggingmodule) to ensure compatibility and proper log rotation [39]. - Log at Proper Levels:

DEBUG: For detailed information during development and troubleshooting.INFO: To confirm user-driven actions or regular operations are working as expected.WARN: For events that might lead to an error in the future (e.g., cache nearing capacity).ERROR: For error conditions that interrupted a process [39].

- Write Meaningful Messages: Every log message should contain sufficient context to understand what happened without needing to look at the source code. For errors, include the operation being performed and the outcome (e.g., "Transaction 2346432 failed: cc number checksum incorrect") [39].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Components for an AIoA Bio-Logging System

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Tri-axial Accelerometer Tag | The primary sensor for measuring surge, sway, and heave acceleration, providing data on animal movement, behavior, and energy expenditure [18]. |

| Data Logging Firmware | Custom software running on the bio-logger that controls sensor sampling, preliminary data processing, and on-device AI model execution for targeted data capture [38]. |