Evaluating Ecological Indicator Performance: From Foundational Concepts to Advanced Validation in Pharmaceutical Innovation

This article provides a comprehensive framework for evaluating ecological indicator performance tailored to pharmaceutical industry researchers and drug development professionals.

Evaluating Ecological Indicator Performance: From Foundational Concepts to Advanced Validation in Pharmaceutical Innovation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for evaluating ecological indicator performance tailored to pharmaceutical industry researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational theory of innovation ecosystems and the 'rainforest model,' examines methodological approaches including entropy-weighted TOPSIS and indicator integration techniques, addresses common troubleshooting challenges in implementation, and presents validation frameworks and comparative analyses of assessment methods. By synthesizing these four core intents, this work establishes a robust foundation for monitoring and enhancing the health of pharmaceutical innovation ecosystems through reliable ecological indicators.

Understanding Ecological Indicators: Core Principles and Pharmaceutical Ecosystem Fundamentals

The concept of "ecological indicators" has traditionally been confined to environmental monitoring, where parameters such as water quality, species diversity, and ecosystem health are tracked to assess natural system conditions. However, this framework possesses significant untapped potential for application in innovation contexts, particularly in pharmaceutical development. Ecological indicators in innovation ecosystems function as measurable parameters that track the health, diversity, productivity, and resilience of the research and development landscape. Just as environmental indicators reveal ecosystem stress or success, innovation indicators can diagnose bottlenecks, predict breakthroughs, and guide strategic investment in drug development pipelines.

This transposition of ecological principles to innovation analysis represents a paradigm shift with substantial implications for research prioritization and resource allocation. In pharmaceutical development, where the journey from concept to market is exceptionally complex and costly, a systematic approach to monitoring the innovation ecosystem enables more efficient navigation of scientific, regulatory, and commercial challenges. This article establishes a structured framework for defining, measuring, and applying ecological indicators specifically within pharmaceutical innovation contexts, providing researchers and drug development professionals with novel methodologies for ecosystem-level analysis.

Theoretical Framework: Ecological Concepts in Innovation Ecosystems

The application of ecological principles to innovation systems requires mapping core biological concepts to their pharmaceutical research counterparts. This conceptual translation enables the adaptation of established ecological monitoring methodologies to track the dynamics of drug development.

Table 1: Conceptual Mapping Between Ecological and Innovation Indicators

| Ecological Concept | Pharmaceutical Innovation Analog | Potential Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| Biodiversity | Therapeutic modality diversity | Number of novel drug classes, proportion of biologics vs. small molecules, platform technology variety |

| Species Population | Pipeline assets by development stage | Investigational New Drug (IND) applications, New Drug Applications (NDA) |

| Ecosystem Health | R&D productivity and sustainability | Success rates by phase, regulatory approval times, investment return |

| Nutrient Cycling | Knowledge transfer and publication | Research publications, patent citations, collaborative networks |

| Habitat Fragmentation | Regulatory and market barriers | Clinical trial complexity, international review disparities |

This conceptual framework reveals that pharmaceutical innovation ecosystems exhibit characteristics remarkably analogous to biological systems, including competition for resources, adaptation to changing environments (regulatory landscapes), and evolutionary selection pressures (market forces). The emerging discipline of innovation ecology thus leverages well-established ecological monitoring methodologies to track the dynamics of drug development [1]. This approach is particularly valuable for identifying indicators that signal ecosystem health or vulnerability, such as diversity thresholds that correlate with sustainable innovation output or concentration risks that precede productivity declines.

Quantitative Indicators for Pharmaceutical Innovation Ecosystems

Robust indicator systems require quantitative metrics that can be tracked over time and compared across different innovation environments. Based on analysis of global pharmaceutical landscapes, several core indicator categories emerge as critical for monitoring innovation ecosystem health.

Table 2: Core Quantitative Indicators for Pharmaceutical Innovation Ecosystems

| Indicator Category | Specific Metrics | Data Source Examples | Application in Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Input Indicators | R&D expenditure, research personnel, orphan designations | Clinical trials databases, corporate reports, regulatory filings | Measures resources invested in innovation generation |

| Process Indicators | Clinical trial approval times, IND/NDA submission volumes, precision medicine trial percentages | Regulatory agency reports, Cortellis Database, scientific publications | Tracks efficiency and focus of development processes |

| Output Indicators | New drug approvals, novel mechanism approvals, publications, patents | FDA/NMPA/EMA approval databases, patent offices, PubMed | Quantifies direct innovation outcomes |

| Impact Indicators | Therapeutic area coverage, market segments addressed, global reach | IMS Health data, epidemiological databases, trade statistics | Assesses broader health and economic effects |

Data from major global markets reveals telling patterns in these indicators. Between 2019 and 2023, China demonstrated a significant rise in both IND applications and NDAs, reflecting a rapidly growing innovation pipeline [2]. Simultaneously, the United States maintained leadership in first-in-class therapies, with the percentage of clinical trials for Likely Precision Medicines (LPMs) showing marked increases across all development phases, particularly in Phase I trials [3]. This indicator trend highlights a strategic shift toward targeted therapies across the global innovation landscape.

The European eco-innovation index provides another relevant model, demonstrating how composite indicators can track system performance over time. Between 2014 and 2024, the EU's eco-innovation index increased by 27.5%, with particularly strong performance in resource efficiency outcomes (62% increase) [4]. This demonstrates how indicator systems can reveal differential performance across ecosystem components, enabling targeted interventions.

Experimental Protocols for Indicator Assessment

TOPSIS Methodology for Indicator Prioritization

The Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to an Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) provides a structured approach for ranking and prioritizing innovation indicators based on their relative importance to specific research or development objectives.

Experimental Protocol:

- Indicator Identification: Compile a comprehensive set of potential indicators from major innovation indexes and industry-specific concerns [5].

- Expert Panel Formation: Convene a multidisciplinary panel of 12-15 experts representing research, clinical development, regulatory affairs, and commercial strategy.

- Evaluation Matrix Construction: Experts rate each indicator on predetermined criteria (e.g., measurability, sensitivity, predictive value, actionability) using a standardized scoring system.

- Ideal Solution Determination: Calculate the ideal and negative-ideal solutions based on the evaluation matrix.

- Similarity Measurement: Compute the relative closeness of each indicator to the ideal solution using Euclidean distance measurements.

- Priority Ranking: Rank indicators based on their similarity scores, with higher values indicating greater priority.

This method facilitates evidence-based selection of indicator sets tailored to specific innovation contexts, such as early research assessment versus late-stage development monitoring. The mathematical rigor of TOPSIS minimizes subjective bias in indicator selection while ensuring alignment with strategic objectives [5].

Biomarker Integration in Clinical Trial Assessment

The role of biomarkers in pharmaceutical innovation ecosystems serves as a specialized indicator category with particular relevance to precision medicine development.

Experimental Protocol:

- Trial Database Mining: Extract all registered clinical trials from comprehensive databases (e.g., Cortellis Competitive Intelligence Clinical Trials Database) [3].

- Biomarker Role Classification: Categorize biomarkers based on their specific roles in trials (e.g., patient stratification, toxicity monitoring, efficacy assessment).

- Precision Medicine Designation: Identify trials employing biomarkers for population targeting as Likely Precision Medicines (LPMs).

- Temporal Trend Analysis: Track the percentage of LPMs across all trial phases over defined time periods (e.g., annual analysis over a decade).

- Correlation Assessment: Examine relationships between LPM percentages and subsequent regulatory outputs (approvals, designations).

This protocol enables quantitative tracking of a critical innovation shift toward targeted therapies, with data showing consistent increases in LPM percentages across all clinical trial phases [3].

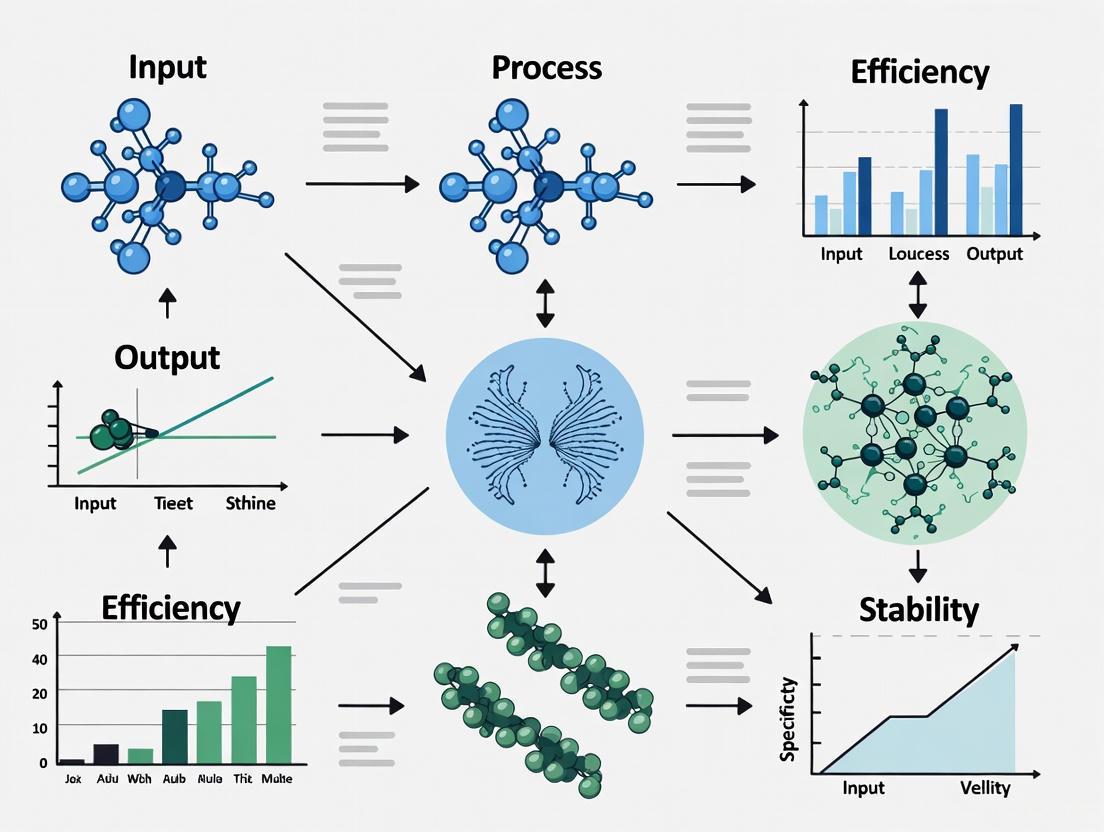

Visualization of Innovation Indicator Frameworks

Effective monitoring of pharmaceutical innovation ecosystems requires clear mapping of indicator relationships and monitoring workflows. The following diagrams provide visual representations of core conceptual frameworks and assessment processes.

Component Relationships in Innovation Ecosystems

Diagram 1: Innovation Indicator Relationships

This framework illustrates how innovation indicators form an interconnected system where inputs enable processes, which generate outputs that create impacts, with feedback loops informing subsequent resource allocation decisions.

Innovation Indicator Assessment Workflow

Diagram 2: Indicator Assessment Workflow

This workflow outlines the sequential process for transforming raw data into strategic insights, beginning with comprehensive data collection and progressing through analytical processing to ecosystem assessment and ultimately decision support.

Research Reagent Solutions for Innovation Monitoring

Systematic assessment of innovation ecosystems requires specialized "research reagents" - methodological tools and data resources that enable standardized measurement and comparison. The following table details essential components of the innovation researcher's toolkit.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Innovation Ecosystem Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Trials Databases (e.g., Cortellis) | Track development pipeline composition and trends | Monitoring therapeutic area focus, modality shifts, trial design evolution | Global coverage, biomarker role classification, phase transitions |

| Regulatory Approval Databases | Measure innovation output and regulatory efficiency | Comparing approval timelines, success rates, first-in-class assessments | Multi-agency coverage, approval condition tracking, international comparisons |

| TOPSIS Analytical Framework | Prioritize indicators based on multiple criteria | Selecting optimal indicator sets for specific assessment objectives | Multi-criteria decision analysis, mathematical rigor, reduced subjectivity |

| Patent Analytics Platforms | Monitor knowledge generation and intellectual property landscapes | Assessing novel mechanism protection, technology evolution | Citation analysis, international filing patterns, claim scope assessment |

| Composite Index Methodologies | Integrate multiple indicators into overall ecosystem assessment | Regional innovation benchmarking, temporal trend analysis | Weighted indicator aggregation, normalization techniques, sensitivity testing |

These research reagents enable standardized, reproducible assessment of innovation ecosystems using the ecological indicator framework. For example, clinical trial databases with detailed biomarker annotation have enabled tracking of the precision medicine transition, revealing that biomarkers for patient stratification now play significant roles across all trial phases [3]. Similarly, composite index methodologies like the EU eco-innovation index demonstrate how multidimensional assessment frameworks can track system evolution over time, with the EU showing a 27.5% improvement in its index score between 2014-2024 [4].

Comparative Analysis of Regional Innovation Ecosystems

Application of ecological indicator frameworks to major pharmaceutical innovation regions reveals distinct ecosystem profiles with characteristic strengths and vulnerabilities. The United States maintains leadership in first-in-class therapies and breakthrough technologies, driven by advanced regulatory pathways, significant R&D investment, and robust research workforce development [2]. The FDA's innovative approaches, including expedited approval pathways and initiatives like Project Orbis, facilitate efficient development and global synchronization of cancer treatment reviews.

China has demonstrated the most rapid transformation, evolving from a generics-dominated market to an increasingly innovation-driven ecosystem. Key indicators show dramatic improvements, including accelerated clinical trial approvals, rising IND and NDA submissions, and growing participation in global multicenter studies [2]. Regulatory modernization through the NMPA has been pivotal in this transition, with implementation of international standards and streamlined review processes.

The European ecosystem shows strong performance in specific indicator categories, particularly resource efficiency outcomes which increased by 62% between 2014-2024 [4]. However, the region faces challenges in maintaining competitive positioning, with indicators suggesting protracted regulatory timelines and complex coordination among member states potentially impeding innovation velocity [2].

This comparative analysis demonstrates how ecological indicator frameworks facilitate evidence-based assessment of regional innovation ecosystems, revealing distinctive profiles that reflect policy environments, investment patterns, and regulatory approaches.

The application of ecological indicators to pharmaceutical innovation contexts provides a powerful framework for ecosystem monitoring, assessment, and management. This approach enables quantitative tracking of ecosystem health, identification of vulnerability signals, and forecasting of developmental trajectories. For drug development professionals and policymakers, these indicator systems offer evidence-based guidance for strategic decision-making, from portfolio optimization to regulatory modernization.

The ongoing evolution of pharmaceutical innovation—characterized by increasing precision medicine focus, novel therapeutic modalities, and globalized development networks—underscores the growing importance of robust ecological indicator frameworks. Future methodological development should emphasize real-time indicator monitoring, predictive modeling of ecosystem trajectories, and standardized assessment protocols enabling cross-regional comparison. As innovation ecosystems continue to increase in complexity, ecological indicator frameworks will provide increasingly vital navigation tools for researchers, companies, and policymakers committed to sustaining pharmaceutical innovation that addresses global health challenges.

The "Rainforest Model" is a conceptual framework for understanding innovation ecosystems, first introduced by Huang and Hollowett in 2012 by comparing Silicon Valley's dynamic environment to a tropical rainforest [6]. This model has since been adapted to analyze the complex, interdependent nature of pharmaceutical innovation, where success depends on the fruitful interaction of diverse actors and environmental conditions [6] [7]. In natural ecosystems, tropical rainforests consist of biotic communities (producers, consumers, decomposers) and abiotic environments (non-living elements like sunlight and water) [6]. Similarly, pharmaceutical innovation ecosystems comprise innovation subjects (enterprises, universities, research institutes, governments, financial institutions) operating within an innovation environment (economic, political, cultural, and physical conditions) [6]. The ultimate aim of this model in pharmaceutical contexts is to create a system where any element can freely link and combine with others to achieve self-breakthrough, though real-world innovation activities often face barriers related to geography, culture, institution, legal frameworks, knowledge, and technology [6].

Core Components of the Pharmaceutical Innovation Rainforest

The pharmaceutical innovation ecosystem can be deconstructed into two primary categories of components, mirroring the structure of natural rainforests.

Innovation Subjects (Biotic Elements)

Pharmaceutical Enterprises: Serve as primary producers and consumers within the ecosystem, driving original innovation and providing services for early technological development [6]. These include both product biotech firms that market their own drugs and platform biotech companies that provide support technologies or conduct specific activities in the innovation process [7].

Universities and Research Institutes: Function as foundational knowledge producers, supporting advances in basic technologies and biotech-related scientific disciplines [7]. They play a crucial role in the research economy, driven by fundamental scientific exploration [7].

Financial Institutions: Provide essential capital resources throughout the innovation lifecycle, from venture funding for early-stage research to financing for clinical trials and market expansion [6] [7].

Governments and Regulatory Bodies: Establish policy frameworks and regulatory pathways that shape the innovation environment, with agencies like the FDA providing critical oversight through approval processes and clinical trial monitoring [6] [7].

Intermediary Service Agencies: Facilitate connections and knowledge flow between different ecosystem elements, acting as key species that shorten communication distances and promote valuable interactions [6].

Innovation Environment (Abiotic Elements)

Economic Conditions: Include factors such as access to financing, market structures, and economic incentives that influence innovation investments and outcomes [6] [7].

Political and Regulatory Frameworks: Comprise government policies, intellectual property systems, regulatory pathways, and compliance requirements that establish the rules governing innovation activities [6] [8].

Cultural Context: Encompasses societal attitudes toward innovation, risk tolerance, entrepreneurial mindset, and collaborative tendencies that affect how ecosystem components interact [6].

Physical Infrastructure: Includes research facilities, laboratory spaces, technological platforms, and transportation networks that provide the physical foundation for innovation activities [6].

Table 1: Core Components of the Pharmaceutical Innovation Rainforest

| Component Type | Elements | Primary Functions | Real-World Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Innovation Subjects | Pharmaceutical Enterprises | Drug discovery, development, and commercialization | Merck, Bristol-Meyers Squibb, Glaxo [9] |

| Universities & Research Institutes | Basic research, knowledge generation, talent development | Research centers in Lombardy ecosystem [7] | |

| Financial Institutions | Funding provision, risk mitigation, resource allocation | Venture capital firms in Boston-Cambridge [7] | |

| Governments & Regulatory Bodies | Policy setting, regulation, incentive structures | FDA, National Cancer Institute [9] [7] | |

| Intermediary Organizations | Connection facilitation, trust building | INBio in Costa Rica [9] | |

| Innovation Environment | Economic Conditions | Resource allocation, market functioning | Venture capital availability, pricing structures [7] |

| Political & Regulatory Frameworks | Rule establishment, compliance monitoring | Intellectual property rights, drug approval pathways [8] | |

| Cultural Context | Behavioral influence, collaboration shaping | Entrepreneurial culture, risk acceptance [7] | |

| Physical Infrastructure | Foundation provision for innovation activities | Research facilities, laboratory spaces [7] |

Quantitative Assessment Frameworks and Methodologies

Evaluating the health and performance of pharmaceutical innovation ecosystems requires multidimensional assessment frameworks that capture both quantitative metrics and qualitative factors.

Health Assessment Index System for Pharmaceutical Innovation

Research on the pharmaceutical industry in Zhejiang, China, from 2011-2019 developed an evaluation index system measuring innovation ecosystem health across seven elements from two aspects: innovation subject and innovation environment [6]. The study employed the entropy weighted TOPSIS method, which calculates indicator weights through entropy method and ranks evaluation objects by their similarity to an ideal solution [6]. This approach effectively eliminates the influence of subjective factors in determining weights and analyzes moving trends in pharmaceutical innovation health [6].

Table 2: Health Assessment Metrics for Pharmaceutical Innovation Ecosystems

| Assessment Dimension | Specific Metrics | Measurement Approaches | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Innovation Subject Development | Resilience of innovation subjects | Survival rates, adaptation capabilities, recovery from setbacks | Zhejiang's three-stage development: stagnation, recovery, development periods [6] |

| Enterprise R&D investment | R&D spending as percentage of revenue, absolute R&D expenditure | Analysis of corporate mergers and acquisitions benefits [6] | |

| Scientific productivity | New Molecular Entities (NMEs), IND applications, patents [8] | Biopharma innovation output measurement [8] | |

| Talent development | Global talent pool building, specialized education programs | "Building a reservoir of global talents" initiative [6] | |

| Innovation Environment Quality | Economic environment | Broadening investment and financing channels [6] | Financial metrics (revenue, profits, costs) tracking [8] |

| Cultural environment | Creating inclusive and open soft environment [6] | Entrepreneurial culture, risk acceptance, collaboration indicators [7] | |

| Policy support | Government policy effectiveness, regulatory efficiency | FDA approval speed, breakthrough designations [8] | |

| Infrastructure development | High-level service chain deployment [6] | Research facilities, technological platforms assessment [7] |

Multidimensional Innovation Rubric for Biopharmaceuticals

A comprehensive analysis of biopharmaceutical innovation measurement identified a six-dimensional rubric through systematic literature review of 617 relevant articles [8]. This framework captures innovation from early discovery to real-world implementation:

Scientific and Technological Advances: Measured through traditional metrics including New Molecular Entities (NMEs), Investigational New Drug (IND) applications, and patents, alongside emerging indicators like AI-enabled R&D and digital biomarkers [8].

Clinical Outcomes: Assessment of therapeutic impact through safety profiles, efficacy measures, patient-reported outcomes, and real-world patient benefits, with emphasis on delays in disease progression [8].

Operational Efficiency: Evaluation of development and production efficiency through trial success rates, R&D timelines, supply chain resilience, and implementation of adaptive trial designs [8].

Economic and Societal Impact: Analysis of economic returns and broader societal benefits through cost-effectiveness analyses, budget impact assessments, and productivity improvements [8].

Policy and Regulatory Effectiveness: Assessment of how regulatory frameworks support innovation through approval speed, breakthrough designations, and surrogate endpoint integration [8].

Public Health and Accessibility: Examination of broader health impacts including reduced disease incidence, healthcare access improvements, and equitable geographic distribution of innovations [8].

Experimental Protocols for Ecosystem Assessment

Entropy Weighted TOPSIS Method for Health Assessment

The entropy weighted TOPSIS method provides an objective approach to evaluating pharmaceutical innovation ecosystem health [6]. The methodological workflow involves sequential stages:

Protocol Details:

Index System Construction: Select seven elements from two aspects (innovation subject and innovation environment) to construct the evaluation index system [6].

Data Collection: Gather time-series data across the evaluation period (e.g., 2011-2019 for Zhejiang study) [6].

Entropy Weight Calculation: Objectively determine the weight of each evaluation indicator based on the information provided by the entropy method, eliminating subjective bias [6].

TOPSIS Implementation: Define the distance between the optimal solution and worst solution of the decision problem [6].

Similarity Calculation: Compute the relative similarity of each solution to the ideal solution [6].

Solution Ranking: Rank solutions as superior or inferior based on similarity scores [6].

Trend Analysis: Analyze moving trends of pharmaceutical innovation ecological rainforest health across the evaluation period [6].

Stakeholder Analysis Framework for Innovation Ecosystems

Research into biopharma innovation ecosystems employs qualitative analysis through verbatim interviews with multiple stakeholders, with data collection and analysis conducted concurrently until theoretical saturation is reached [7]. This approach identifies key stakeholders and their roles in value creation within the ecosystem.

Experimental Protocol:

Research Design: Structure the investigation according to grounded theory methodology, allowing themes to emerge from the data rather than imposing pre-conceived frameworks [7].

Data Collection: Conduct verbatim interviews with diverse ecosystem stakeholders, including industry representatives, academic researchers, government officials, and investors [7].

Concurrent Analysis: Perform data collection and analysis simultaneously until saturation is reached, where all data are identified and their consistency across multiple sources is established [7].

Stakeholder Mapping: Identify the multilevel and longitudinal set of key stakeholders required in a biopharma innovation ecosystem [7].

Role Identification: Define the specific role of each stakeholder with regard to comparative advantages required in ecosystem engagement [7].

Driving Force Analysis: Trace ecosystem dynamics through analysis of the innovation ecosystem's driving forces from a holistic perspective [7].

Comparative Analysis of Innovation Models

Regional Ecosystem Performance Indicators

The regional ecosystem approach emphasizes spatial boundaries as important variables for describing ecosystems based on economic activities [7]. Comparative studies of biotechnology clusters in Cambridge (MA), Cambridge (England), and Germany identify common success factors [7].

Table 3: Regional Innovation Ecosystem Comparative Performance

| Performance Indicator | Silicon Valley Model | Lombardy Case Study | Boston-Cambridge Ecosystem |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scientific Research Base | Exceptional development with Stanford University [6] | Well-developed scientific base [7] | Exceptionally well-developed with Harvard, MIT [7] |

| Collaboration Management | Mutual beneficial symbiosis [6] | Associations managing collective affairs [7] | Formal and informal network structures [7] |

| Funding Mechanisms | Rapid flow of innovative elements [6] | Local venture capital presence [7] | Strong local venture capital ecosystem [7] |

| Research Infrastructure | Nonlinear self-organization [6] | Infrastructure for biotechnology commercialization [7] | Specialized research facilities and platforms [7] |

| Public Support | Government as innovation subject [6] | National and regional public funding [7] | Significant public research funding [7] |

| Key Success Factors | Biodiversity accumulation [6] | Convergence of public and private initiatives [7] | Complex interactions to sustain biotech sector [7] |

Stakeholder Adoption of Innovation Metrics

Different stakeholders within pharmaceutical innovation ecosystems prioritize distinct innovation metrics based on their strategic objectives and operational contexts [8]. The alignment of measurement approaches across stakeholder groups significantly influences ecosystem functionality.

Table 4: Stakeholder Adoption of Innovation Metrics by Dimension

| Innovation Dimension & Metrics | Pharmaceutical Companies | Investors | Payers | Policymakers | Patients |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scientific & Technological Advances | High adoption (NMEs, patents) [8] | High adoption (platform innovations) [8] | Low adoption [8] | Low adoption [8] | Low adoption [8] |

| Clinical Outcomes | High adoption (efficacy, safety) [8] | Medium adoption [8] | High adoption (quality of life) [8] | High adoption [8] | High adoption [8] |

| Operational Efficiency | High adoption (R&D efficiency) [8] | High adoption (success rates) [8] | Low adoption [8] | Low adoption [8] | Not applicable |

| Economic & Societal Impact | High adoption (financial metrics) [8] | High adoption (revenue, profits) [8] | High adoption (cost-effectiveness) [8] | Medium adoption [8] | Low adoption [8] |

| Policy & Regulatory Effectiveness | High adoption (approval speed) [8] | Medium adoption [8] | Medium adoption [8] | High adoption (regulatory incentives) [8] | Medium adoption [8] |

| Public Health & Accessibility | Low adoption [8] | Medium adoption [8] | High adoption (health impact) [8] | High adoption (healthcare equity) [8] | High adoption (geographic reach) [8] |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Ecosystem Analysis

The study of innovation ecosystems requires specific methodological tools and approaches that function as "research reagents" for analyzing ecosystem health and functionality.

Table 5: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Innovation Ecosystem Analysis

| Research Reagent | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Entropy Weighted TOPSIS Method | Objectively evaluates ecosystem health by calculating indicator weights and ranking solutions by similarity to ideal state [6] | Pharmaceutical innovation ecosystem health assessment [6] |

| Stakeholder Interview Protocols | Collects qualitative data on ecosystem dynamics from multiple perspectives within the innovation landscape [7] | Identifying roles and value creation processes in biopharma innovation ecosystems [7] |

| Multidimensional Innovation Rubric | Comprehensively evaluates biopharmaceutical innovation across six dimensions from discovery to implementation [8] | Measuring innovation quality and impact beyond traditional volume-based indicators [8] |

| Obstacle Factor Diagnosis Model | Identifies key factors hindering innovation development within the ecosystem [6] | Diagnosing innovation barriers in pharmaceutical industry contexts [6] |

| Regional Ecosystem Ranking Framework | Assesses and compares regional innovation capacities through standardized indicators [7] | Comparative analysis of biotechnology clusters across different geographic regions [7] |

| Biomass-Relative Water Availability Metric | Measures resource availability per unit of biomass in natural rainforests, providing analogy for innovation resource allocation [10] | Assessing whether ecosystem resources adequately support constituent elements [10] |

The Rainforest Model provides a robust framework for understanding and evaluating pharmaceutical innovation ecosystems. Research indicates that resilience of innovation subjects, followed by economic and cultural environment factors, are key determinants of ecosystem health [6]. Effective ecosystem management requires deploying high-level service chains, broadening investment and financing channels for enterprises, building global talent pools, and creating inclusive, open soft environments [6]. The multidimensional assessment of innovation should incorporate clinical effectiveness, patient-centered outcomes, and broader societal impact alongside traditional volume-based indicators to better align investment and R&D incentives with high-value, transformative innovation [8]. This approach brings innovation policy closer to patient needs and societal priorities, ensuring that innovative therapies are recognized for both their scientific merit and real-world impact [8].

In pharmaceutical research, the concept of "innovation subjects" refers to the tangible tools, technologies, and biological entities that directly drive discovery forward. These include biomarkers, artificial intelligence algorithms, specific therapeutic modalities, and measurement technologies that form the core of research activities. In contrast, "innovation environments" encompass the organizational structures, cultural frameworks, regulatory pathways, and strategic ecosystems that enable these subjects to flourish. Understanding the dynamic interaction between these components is critical for advancing pharmaceutical innovation, particularly when viewed through the lens of ecological indicator performance evaluation, which assesses how these elements function within a complex, adaptive system.

The pharmaceutical industry stands at a pivotal juncture, marked by both unprecedented scientific opportunity and persistent productivity challenges. While research and development spending has reached over $50 billion annually, the number of new molecular entities approved has declined to levels seen decades ago, with clinical success rates averaging just 16% [11]. This innovation paradox has forced a fundamental re-examination of both the subjects and environments that constitute the pharmaceutical research ecosystem. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these key components, offering researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals a structured framework for evaluating their performance and interoperability.

Performance Comparison: Innovation Subjects vs. Environments

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Key Innovation Subjects

| Innovation Subject | Primary Function | Performance Impact | Development Timeline | Success Rate/Reliability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AI/ML in Drug Discovery | Accelerate target identification & compound screening | Reduces preclinical timelines by 25-50% [12] | Implementation: 12-24 months | Expected to drive 30% of new drugs by 2025 [12] |

| Biomarkers (Diagnostic) | Detect/confirm presence of disease or condition | Enables precise patient stratification | Validation: 24-60 months [13] | Variable; requires rigorous analytical/clinical validation [14] |

| Biomarkers (Predictive) | Identify patients likely to respond to treatment | Increases clinical trial success probability | Qualification: 36-72 months [13] | High impact but complex validation (e.g., BRCA1/2) [13] |

| Real-World Evidence (RWE) | Generate clinical insights beyond traditional trials | Optimizes product lifecycle management [15] | Implementation: 6-18 months | Regulatory acceptance growing (e.g., FDA, EMA) [15] |

| In Silico Trials | Computer simulations to predict drug efficacy | Reduces need for animal testing; accelerates development [15] | Model development: 12-36 months | Regulatory interest increasing; qualification essential [15] |

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Innovation Environments

| Innovation Environment | Primary Function | Performance Impact | Implementation Timeline | Success Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AI-Ready Organizational Culture | Enable technology adoption & transversal use | Critical for capturing AI value; improves decision patterns [12] | Cultural shift: 24-48 months | Requires upskilling, trust in data, and leadership commitment [12] |

| Strategic M&A Partnerships | Address portfolio gaps and access innovation | Reinforces pipelines; accelerates time to market [16] | Deal execution: 6-18 months | Alignment with corporate strategy; therapeutic expertise fit [16] |

| Sustainability-Focused Operations | Reduce environmental impact while maintaining performance | Enhances long-term competitiveness; meets regulations [15] [17] | Transformation: 36-72 months | Balanced focus on environment, internal processes, customers [17] |

| Performance Measurement Systems | Balance metrics with researcher motivation | Optimizes research productivity and creativity [18] | System design: 12-24 months | Must match industrialization level of research activity [18] |

| Biomarker Qualification Pathway | Regulatory framework for biomarker adoption | Reduces uncertainty in regulatory decisions [14] | Process: 24-60+ months | Collaborative development; clear Context of Use [14] |

Table 3: Cross-Component Synergy Analysis

| Subject-Environment Pairing | Performance Interaction | Efficiency Gain | Implementation Challenge | Ecological Indicator |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AI Tools + AI-Ready Culture | Technology potential only realized with cultural adaptation [12] | 25-50% timeline reduction in preclinical stages [12] | Resistance to change; data trust issues | Adoption transversality index |

| Biomarkers + Qualification Pathway | Regulatory certainty enables broader application [14] | Accelerates regulatory approval decisions | Resource-intensive evidence generation | Qualification success rate |

| RWE + Flexible Regulatory Environments | Faster adoption in regulatory decision-making [15] | Optimizes post-market surveillance | Data standardization across sources | Regulatory acceptance rate |

| In Silico Models + Performance Metrics | Balanced measurement enables innovation [18] | Reduces late-stage failures through better prediction | Risk of misaligned incentives | Model predictability index |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Biomarker Validation and Qualification Protocol

The validation of biomarkers represents a critical experimental protocol bridging innovation subjects and environments. The FDA's Biomarker Qualification Program outlines a rigorous three-stage methodology for establishing biomarkers as reliable tools for regulatory decision-making [14]:

Stage 1: Letter of Intent (LOI) Submission

- Objective: Establish initial feasibility and address unmet drug development need

- Methodology: Submit comprehensive LOI containing biomarker specifications, proposed Context of Use (COU), measurement approach, and preliminary scientific rationale

- Output: FDA acceptance permits progression to Qualification Plan development

- Duration: Typically 30-60 days for agency review and response

Stage 2: Qualification Plan (QP) Development

- Objective: Create detailed biomarker development plan addressing knowledge gaps

- Methodology: Comprehensive proposal outlining analytical validation, biological rationale, and clinical applicability, including:

- Systematic literature review and evidence synthesis

- Analytical method validation specifications

- Proposed studies to address evidence gaps

- Statistical analysis plan for biomarker performance

- Output: Accepted QP provides roadmap for Full Qualification Package

- Duration: 6-12 months for development and agency review

Stage 3: Full Qualification Package (FQP) Submission

- Objective: Compile comprehensive evidence supporting biomarker qualification

- Methodology: Integrated evidence dossier containing:

- Complete analytical validation data

- Clinical or preclinical verification studies

- Assessment of biomarker reliability across populations

- Final statistical analysis of biomarker performance

- Output: FDA qualification decision for specified COU

- Duration: 12-24 months for evidence generation and agency review

This experimental framework transforms biomarkers from exploratory tools into qualified decision-making instruments, demonstrating the essential interaction between innovation subjects (the biomarkers themselves) and environments (the regulatory qualification pathway).

AI Implementation and Organizational Readiness Assessment

The integration of artificial intelligence into drug discovery requires both technical implementation and organizational adaptation. The following experimental protocol assesses both dimensions:

Phase 1: Infrastructure and Data Readiness Assessment

- Objective: Evaluate technical and data foundations for AI implementation

- Methodology:

- Conduct data architecture audit assessing quality, accessibility, and standardization

- Establish computational infrastructure requirements for intended AI applications

- Implement data governance framework ensuring quality and compliance

- Develop baseline metrics for current discovery workflows

- Success Indicators: Data accessibility indexes, preprocessing efficiency metrics

Phase 2: Pilot Implementation and Validation

- Objective: Demonstrate AI value in focused application areas

- Methodology:

- Select 2-3 high-value use cases (e.g., target identification, compound screening)

- Implement "snackable AI" tools integrated into researcher workflows [12]

- Design comparative studies measuring AI-enhanced vs. traditional approaches

- Establish performance metrics including time reduction, cost savings, and success rate improvement

- Success Indicators: 25-50% reduction in preclinical timeline, improved prediction accuracy [12]

Phase 3: Organizational Integration and Scaling

- Objective: Transform organizational culture and processes to leverage AI capabilities

- Methodology:

- Assess cultural readiness through surveys and focus groups

- Implement targeted upskilling programs matching AI capabilities to researcher needs

- Establish transversal AI governance crossing traditional functional boundaries

- Redesign decision-making processes to incorporate AI-derived insights

- Monitor adoption metrics and qualitative feedback on organizational resistance

- Success Indicators: AI adoption rates, decision pattern changes, productivity improvements

This protocol emphasizes that successful AI implementation requires simultaneous attention to both the technological capabilities (innovation subject) and the organizational context (innovation environment), with performance metrics tracking both dimensions.

Visualization of Relationships and Workflows

Pharmaceutical Innovation Ecosystem

Biomarker Qualification Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Platforms for Innovation Components

| Research Solution | Primary Application | Function in Research | Compatibility/Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient-Derived Organoids | Preclinical biomarker validation [19] | 3D culture systems replicating human tissue biology for biomarker discovery | Requires specialized media, extracellular matrix; compatible with high-throughput screening |

| Digital Twin Platforms | In silico trial implementation [16] | Virtual replicas of patients for testing drug candidates in early development | Integration with clinical data, AI algorithms, and simulation software |

| Liquid Biopsy Assays | Clinical biomarker detection [19] | Non-invasive cancer detection through circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) analysis | Requires blood collection systems, DNA extraction kits, NGS platforms |

| Multi-Omics Integration Platforms | Biomarker discovery & validation [19] | Combines genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics for comprehensive biomarker profiling | Bioinformatics infrastructure, data standardization protocols, computational resources |

| CRISPR-Based Functional Genomics | Target identification & validation [19] | Identifies genetic biomarkers influencing drug response through systematic gene modification | Cell culture systems, gRNA libraries, delivery vectors, sequencing validation |

| Humanized Mouse Models | Immunotherapy biomarker discovery [19] | Mice engineered with human immune system components for immuno-oncology research | Specialized breeding facilities, human cell engraftment protocols, immune monitoring tools |

| AI/ML Algorithm Suites | Drug discovery acceleration [15] [12] | Identifies potential drug targets, predicts molecular interactions, optimizes trial designs | High-performance computing, curated training datasets, domain expertise integration |

| Real-World Evidence Platforms | Post-market evidence generation [15] | Analyzes data from wearables, medical records, patient surveys for regulatory decisions | Data integration capabilities, privacy compliance frameworks, analytics infrastructure |

Comparative Performance Analysis and Ecological Indicators

The interaction between innovation subjects and environments creates a dynamic ecosystem whose performance can be measured through ecological indicators adapted from environmental science. These indicators assess the health, productivity, and sustainability of the pharmaceutical innovation landscape:

Resource Efficiency Indicators measure how effectively the innovation ecosystem converts inputs into valuable outputs. AI implementation shows promising efficiency gains, reducing preclinical drug discovery timelines by 25-50% and potentially generating up to 11% in value relative to revenue across functional areas [12] [16]. This efficiency metric parallels ecological productivity measures, assessing output per unit input in the innovation pipeline.

Resilience and Adaptation Indicators evaluate the system's capacity to withstand disruptions and adapt to changing conditions. The biomarker qualification process demonstrates regulatory resilience, with its structured three-stage pathway creating predictable adaptation mechanisms for incorporating new scientific approaches [14]. Similarly, organizations that successfully implement "performance-driven empowerment" in their measurement systems show higher resilience to productivity pressures while maintaining creativity [18].

Diversity and Synergy Indicators assess the variety of components and their productive interactions. The trend toward multimodal data strategies, combining clinical, genomic, and patient-reported data, creates synergistic effects that enhance innovation capacity [16]. Companies that balance their focus across multiple dimensions—environment, internal processes, customers, finance, learning and growth, and society—demonstrate more sustainable performance profiles [17].

Sustainability Indicators measure long-term viability rather than short-term outputs. The pharmaceutical industry's increasing attention to environmental impact, with some companies generating 1.5 times more CO2 than the automotive industry, has prompted sustainability initiatives that align with broader ecological stewardship principles [17]. This environmental performance is increasingly linked to business success, with investors applying sustainability criteria when evaluating company performance [17].

Through these ecological indicators, researchers and drug development professionals can assess the overall health of their innovation ecosystems, identifying areas where strengthening either innovation subjects or their enabling environments will yield the greatest improvement in pharmaceutical R&D productivity and sustainability.

The conceptual framework of "innovation ecosystems" has gained substantial traction among researchers, policymakers, and business strategists seeking to understand the drivers of economic growth and technological advancement [20]. This paradigm recognizes that innovation is not an isolated activity but a complex process emerging from a dynamic network of interactions among diverse actors [21]. Just as biological ecosystems thrive on biodiversity and symbiotic relationships, innovation ecosystems depend on variety and productive interdependencies to foster resilience and performance.

This guide adopts an ecological indicator performance evaluation framework to objectively compare the health and functionality of innovation ecosystems. We present standardized metrics and methodologies to assess two core ecological characteristics—biodiversity and mutually beneficial symbiosis—enabling researchers and drug development professionals to diagnose ecosystem vitality, identify performance gaps, and implement strategies for enhanced innovation output.

Theoretical Framework: Core Ecological Concepts

Defining the Innovation Ecosystem

An innovation ecosystem constitutes the evolving set of actors, activities, and artifacts, and the institutions and relations—including both complementary and substitute relationships—that are critically important for the innovative performance of an actor or a population of actors [20]. This synthesized definition captures the complexity of these systems, emphasizing that they encompass not only collaboration but also competition, and include both human actors and the artifacts they create.

These ecosystems are characterized by several key principles: interdependence between participants, continuous flow of knowledge, talent, and capital, shared infrastructure and resources, and a culture of experimentation and risk-taking [21]. Unlike traditional linear innovation models, ecosystems are fluid, adaptable networks whose strength derives from the density and quality of interactions among participants [21].

Biodiversity in Innovation Contexts

In ecological terms, biodiversity refers to the variety of life at genetic, species, and ecosystem levels. Translated to innovation contexts, biodiversity manifests as:

- Actor Diversity: The variety of organizations including startups, small and medium enterprises (SMEs), large corporations, research institutions, universities, government agencies, investors, financial institutions, incubators, accelerators, and end-users [21].

- Functional Diversity: The range of specialized roles and capabilities present within the ecosystem, from basic research to commercialization expertise.

- Cognitive Diversity: Variation in knowledge bases, disciplinary backgrounds, and problem-solving approaches among participants.

High biodiversity enhances ecosystem resilience by providing functional redundancy and enabling adaptive responses to environmental shocks and technological disruptions.

Symbiosis as Mutualistic Interaction

In biology, symbiosis represents any close and long-term biological interaction between two different biological species, traditionally categorized into mutualism, commensalism, and parasitism [22]. Mutualism describes relationships where both species benefit, such as the symbiosis between coral and photosynthetic algae where the coral receives energy compounds while providing the algae with a protected environment and nutrient compounds [23].

In innovation ecosystems, mutualistic symbiosis occurs when different organizations engage in relationships that generate reciprocal benefits, such as:

- Knowledge sharing between universities and industries

- Venture capital investments in promising startups

- Corporate partnerships with research institutions

- Supplier networks that co-develop components

These symbiotic relationships modify the physiology and influence the ecological dynamics and evolutionary processes of interacting partners, ultimately altering their competitive capabilities and market distributions [24].

Performance Evaluation Framework

The health of an innovation ecosystem can be systematically evaluated using an input-output structure that assesses the conditions favoring innovation creation and the resulting economic and technological improvements [25]. This framework enables standardized comparison across different ecosystems and temporal tracking of performance evolution.

Table 1: Innovation Ecosystem Performance Indicators Framework

| Category | Subcategory | Specific Metrics | Data Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Innovation Inputs (Enabling Conditions) | Human Capital & Research | STEM graduates, R&D personnel, research publications | National statistics, institutional reports [25] |

| Infrastructure & Institutions | ICT infrastructure, regulatory quality, intellectual property protection | World Bank indicators, patent databases [25] | |

| Innovation Linkages | University-industry collaborations, cross-border co-patents | Innovation surveys, publication data [25] | |

| Innovation Inputs (Market Conditions) | Financial Support | Early-stage funding, VC availability, R&D expenditure | Investment reports, financial databases [25] [26] |

| Business Dynamics | Startup density, scaleup ratio, market entry/exit rates | Business registries, corporate databases [25] | |

| Innovation Outputs | Knowledge & Technology | Patents, high-impact publications, software creation | Patent offices, citation databases [26] |

| Economic Impacts | Employment growth, production value, ecosystem value | National accounts, corporate reporting [25] [26] |

Biodiversity Assessment Protocol

The following experimental protocol provides a standardized methodology for quantifying biodiversity within innovation ecosystems:

Objective: To measure and compare the actor diversity and functional variety within defined innovation ecosystems.

Data Collection Methodology:

- Ecosystem Boundary Definition: Delimit the geographical, technological, or institutional boundaries of the ecosystem under study.

- Actor Census: Identify and categorize all participating entities using a standardized taxonomy (e.g., FIRMS: Startups, SMEs, Large Corporations; RESEARCH: Universities, R&D Institutes; SUPPORT: Investors, Incubators, Government Agencies).

- Capability Mapping: Document the specialized functions and resources each actor contributes to the ecosystem.

Quantitative Analysis:

- Richness Calculation: Count the number of distinct actor categories present.

- Evenness Measurement: Assess the distribution of actors across categories using Shannon Diversity Index.

- Functional Redundancy: Calculate the number of actors providing similar functions within the ecosystem.

Benchmarking: Compare biodiversity metrics against reference ecosystems or track temporal changes.

Table 2: Biodiversity Metrics for Selected Global Innovation Ecosystems

| Ecosystem | Actor Richness (Categories) | Shannon Diversity Index | Functional Redundancy Score | Specialization Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silicon Valley | 9.5 | 2.1 | 8.7 | 0.76 |

| London | 8.8 | 1.9 | 7.9 | 0.72 |

| Boston | 8.2 | 1.8 | 7.2 | 0.81 |

| Paris | 7.9 | 1.7 | 6.8 | 0.69 |

| Bengaluru | 7.5 | 1.6 | 6.1 | 0.74 |

Symbiotic Relationship Assessment Protocol

This protocol evaluates the prevalence and quality of mutualistic interactions within innovation ecosystems:

Objective: To identify, classify, and measure the impact of symbiotic relationships among ecosystem participants.

Data Collection Methodology:

- Relationship Mapping: Document formal and informal interactions through structured interviews, partnership announcements, co-patent analysis, and investment flows.

- Benefit-Reciprocity Assessment: Classify relationships using a modified biological symbiosis typology:

- Mutualism: Both organizations derive significant benefits

- Commensalism: One benefits without significantly affecting the other

- Parasitism: One benefits at the other's expense

- Outcome Tracking: Measure relationship durability, resource flows, and innovation outputs.

Quantitative Analysis:

- Symbiosis Density: Calculate the ratio of mutualistic relationships to total organizations.

- Relationship Strength: Measure the resource commitment and interaction frequency.

- Innovation Yield: Track joint patents, co-publications, and collaborative products.

Validation: Correlate symbiosis metrics with ecosystem performance indicators.

Symbiosis Assessment Workflow: This diagram illustrates the standardized protocol for evaluating mutualistic relationships within innovation ecosystems, from initial boundary definition to final performance correlation.

Comparative Performance Analysis

Global Ecosystem Benchmarking

The Global Startup Ecosystem Report provides comparative data that enables objective performance evaluation across leading innovation hubs worldwide. When analyzed through an ecological lens, distinct patterns emerge regarding the relationship between biodiversity, symbiosis, and innovation outcomes.

Table 3: Global Startup Ecosystem Rankings and Key Success Factors (2025)

| Ecosystem | Global Rank | Performance Score | Funding Score | Talent & Experience | Market Reach | Knowledge |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silicon Valley | 1 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| New York City | 2 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 9 | 8 |

| London | 3 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 9 |

| Boston | 4 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 7 | 9 |

| Beijing | 5 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 8 |

| Shanghai | 10 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 7 |

| Paris | 12 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| Bengaluru | 14 | 7 | 6 | 8 | 6 | 7 |

Case Study: Pharmaceutical Innovation Ecosystems

The pharmaceutical sector provides a compelling context for analyzing biodiversity and symbiosis, given its dependence on complex R&D networks and diverse expertise pools. Healthy drug development ecosystems exhibit characteristic biodiversity patterns:

- Cross-Sector Collaboration: Integration between academic research institutions, biotech startups, large pharmaceutical corporations, clinical research organizations, and regulatory bodies [27].

- Specialized Complementarity: Coexistence of organizations with distinct but complementary capabilities, from basic disease mechanism research to clinical trial management and commercialization.

- Knowledge Symbiosis: Mutualistic relationships where academic institutions provide fundamental research insights while industry partners contribute scaling expertise and market access.

Ecosystems with robust biodiversity and symbiosis demonstrate superior performance in converting basic research into approved therapies, as measured by clinical trial success rates and regulatory approval timelines.

Research Reagent Solutions for Ecosystem Analysis

The methodological toolkit for innovation ecosystem research comprises specialized analytical approaches and data resources that enable rigorous assessment of biodiversity and symbiotic relationships.

Table 4: Essential Research Toolkit for Innovation Ecosystem Analysis

| Research Tool | Primary Function | Application Example | Data Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stakeholder Network Analysis | Maps formal/informal relationships between ecosystem actors | Identifying knowledge flow patterns in biotechnology clusters | Relationship matrices, centrality measures |

| Patent Co-classification Analysis | Tracks technological convergence and knowledge recombination | Measuring cross-disciplinary innovation in drug delivery systems | Technology proximity maps, collaboration indices |

| Venture Capital Flow Mapping | Quantifies financial resource allocation across ecosystem segments | Analyzing investment patterns in early-stage vs. late-stage biotech | Funding concentration metrics, sectoral distribution |

| Research Publication Co-authorship Analysis | Measures institutional collaboration patterns | Assessing university-industry knowledge transfer efficiency | Collaboration networks, knowledge diffusion rates |

| Innovation Output Benchmarking | Compares ecosystem performance against reference standards | Evaluating therapeutic area specialization across regions | Specialization indices, comparative advantage measures |

This comparison guide has established an ecological framework for evaluating innovation ecosystem health through the dual lenses of biodiversity and mutualistic symbiosis. The standardized metrics, experimental protocols, and visualization tools presented enable researchers and drug development professionals to conduct objective, comparative assessments of ecosystem vitality.

The evidence demonstrates that high-performing innovation ecosystems consistently exhibit greater actor diversity, functional variety, and dense networks of mutually beneficial relationships. These ecological characteristics correlate strongly with enhanced innovation output, economic impact, and adaptive resilience in the face of technological disruption [25] [26].

For practitioners seeking to enhance ecosystem health, the implications are clear: foster biodiversity by attracting and retaining diverse organizational types; facilitate symbiosis by creating platforms for productive interaction; and continuously monitor ecosystem vital signs using the standardized metrics outlined in this guide. Future research should further refine these ecological indicators and establish normative benchmarks specific to pharmaceutical and biotechnology innovation contexts.

Historical Evolution of Ecological Indicator Development in Regulatory and Research Contexts

Ecological indicators have emerged as indispensable tools for assessing environmental conditions, tracking changes, and informing policy decisions. These indicators serve as practical proxies for measuring environmentally relevant phenomena where direct measurement is impractical or impossible [28]. The development of ecological indicators represents a dynamic interplay between scientific research and regulatory frameworks, evolving from simple single-species observations to sophisticated multidimensional assessment systems.

This evolution has been driven by the growing recognition that effective environmental management requires robust, scientifically-grounded metrics that can bridge the gap between complex ecological systems and decision-making processes. As boundary objects inhabiting several intersecting social worlds, indicators must satisfy the informational requirements of both scientific communities and policy makers [28]. This review examines the historical progression of ecological indicator development within regulatory and research contexts, comparing their performance across different applications and providing methodological guidance for their implementation.

Historical Trajectory of Ecological Indicator Development

Conceptual Foundations and Early Development

The theoretical foundation for ecological indicators established them as components or measures of environmentally relevant phenomena used to depict or evaluate environmental conditions or changes [28]. Early ecological indicators primarily consisted of single-species observations and physical-chemical measurements that provided limited snapshots of environmental health. The indicator-indicandum relationship formed the core conceptual framework, where an indicator (indicans) served as a measure from which conclusions about the phenomenon of interest (indicandum) could be inferred [28].

During this formative period, the ambiguity of terminology posed significant challenges for the field. Different scientific disciplines and regulatory bodies employed varying definitions of what constituted an indicator, leading to difficulties in comparing research findings and implementing consistent policies [28]. This definitional ambiguity highlighted the need for standardized concepts that could accommodate the diverse applications of ecological indicators while maintaining scientific rigor.

The Rise of Multidimensional Assessment Frameworks

By the late 20th century, ecological indicator development had shifted toward multidimensional frameworks that integrated multiple aspects of ecosystem health. Landscape assessment research began systematically categorizing indicators into six primary classes: ecological, historical-cultural, socioeconomic, land use, environmental, and perceptual indicators [29].

Table 1: Historical Evolution of Ecological Indicator Frameworks

| Time Period | Dominant Approach | Key Indicators | Regulatory Influence | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-1980s | Single-species & physical-chemical | Indicator species, water quality parameters | Command-and-control regulations [30] | Narrow scope, limited ecological context |

| 1980s-1990s | Early multimetric indices | Biotic indices, habitat quality metrics | Market-based instruments [30] | Limited integration across domains |

| 1990s-2000s | Integrated assessments | Ecological, land use, environmental indicators [29] | Voluntary regulations [30] | Underrepresentation of socio-cultural factors |

| 2000s-Present | Holistic sustainability frameworks | SUVA, FIVA, ENVA, SOVA [31] [32] | Climate-focused governance [30] | Implementation complexity, weighting challenges |

The integration level across these indicator categories revealed significant gaps in assessment approaches. A comprehensive analysis of 239 studies found that only 5% incorporated all six indicator categories, with the most frequent combinations being ecological and land use indicators [29]. Historical-cultural and perceptual indicators were the least represented, appearing in just 6% and 7% of studies respectively [29]. This integration gap highlighted the disciplinary silos that continued to characterize ecological assessment despite calls for more holistic approaches.

Regulatory Drivers and Policy Integration

The evolution of environmental regulations significantly influenced indicator development trajectories. Regulatory approaches have traditionally been categorized into three main types: command-and-control (direct regulation through standards and prohibitions), market-based (economic instruments), and voluntary (soft instruments including commitments and agreements) [30].

Comparative Analysis of Ecological Indicator Performance

Application Across Environmental Domains

Ecological indicators have been developed and applied across diverse environmental domains, with varying levels of effectiveness and adoption. The performance of different indicator types depends largely on their specific application context and the management questions they seek to address.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Major Ecological Indicator Categories

| Indicator Category | Measurement Focus | Common Metrics | Primary Applications | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ecological | Ecosystem structure & function | Species richness, population trends, habitat quality [29] | Conservation planning, impact assessment | Direct ecological relevance, scientific acceptance | Data intensive, taxonomic expertise required |

| Land Use | Landscape patterns & changes | Land cover classes, fragmentation metrics, connectivity [29] | Spatial planning, policy monitoring | Geospatial data availability, standardized methods | May not capture ecological processes |

| Socioeconomic | Human-environment interactions | Resource use, economic costs, management expenditures [29] | Sustainable development, policy evaluation | Links ecology to human systems | Difficult to standardize across regions |

| Historical-Cultural | Long-term human influences | Traditional knowledge, cultural significance, historical continuity [29] | Cultural resource management, restoration | Captures temporal depth, cultural values | Qualitative, subjective measurements |

| Environmental | Physical & chemical conditions | Water/air quality, soil parameters, pollution levels [29] | Regulatory compliance, pollution control | Objective, quantifiable, standardized | Limited biological integration |

| Perceptual | Human landscape experience | Visual quality, tranquility, sense of place [29] | Landscape planning, tourism development | Captures human dimensions | Highly subjective, culturally variable |

Emerging Integrated Assessment Frameworks

Recent approaches have focused on integrating multiple indicator types to provide more comprehensive sustainability assessments. The Sustainable Value Added (SUVA) framework represents one such approach, integrating three dimensions: Financial Value Added (FIVA), Environmental Value Added (ENVA), and Social Value Added (SOVA) [31] [32].

Unlike earlier frameworks like the Sustainability Balanced Scorecard (SBSC) that maintain a strict hierarchy with financial indicators at the top, SUVA employs a bottom-up approach that allows environmental and social dimensions to be assessed independently of financial metrics [32]. This framework enables systematic assessment by comparing targeted and achieved values across multiple sustainability dimensions, with weights assignable at each level according to specific contexts [31].

Methodological Protocols for Indicator Development and Application

Indicator Validation and Testing Protocols

The development of robust ecological indicators requires rigorous validation methodologies to ensure their reliability and relevance. While specific protocols vary by indicator type and application, several key methodological principles emerge across contexts.

Table 3: Standardized Experimental Protocol for Indicator Validation

| Protocol Phase | Key Activities | Data Requirements | Quality Controls |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conceptual Framework | Define indicator-indicandum relationship, establish assessment goals | Literature review, expert consultation, stakeholder input | Clear logical framework, explicit assumptions |

| Field Sampling | Systematic data collection, spatial and temporal replication | Field measurements, remote sensing, surveys | Standardized methods, randomization, quality assurance |

| Data Analysis | Statistical modeling, trend analysis, validation against reference conditions | Environmental datasets, long-term monitoring data | Appropriate statistical power, handling of missing data |

| Interpretation | Establish reference conditions, define thresholds, uncertainty assessment | Historical data, paired-site comparisons, expert judgment | Transparent uncertainty quantification, sensitivity analysis |

The conceptual foundation begins with precisely defining the indicator term and its relationship to the phenomenon of interest [28]. This requires clearly establishing the correlation between an indicator and indicandum, with the strength of this correlation determining the indicator's effectiveness [28]. Subsequent phases implement systematic sampling designs, statistical validation, and careful interpretation contextualized within well-defined reference conditions.

Indicator Integration and Assessment Workflow

Integrating multiple ecological indicators requires a structured approach to reconcile different data types, measurement scales, and disciplinary perspectives. The following workflow visualization illustrates the logical sequence for developing integrated ecological assessments:

This integration workflow highlights the systematic process required for comprehensive ecological assessment, from initial goal definition through final interpretation. The most significant challenges occur at the integration phase, where indicators from different categories must be reconciled despite potential contradictions and measurement incompatibilities.

Successful development and application of ecological indicators requires specialized methodological approaches and analytical tools. The selection of appropriate methods depends on the specific research questions, ecological context, and regulatory framework.

Table 4: Essential Research Toolkit for Ecological Indicator Development

| Method Category | Specific Tools/Techniques | Primary Applications | Data Outputs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Field Sampling Methods | Systematic plots, transects, remote sensing, automated sensors | Data collection across spatial and temporal scales | Species counts, physical measurements, imagery |

| Statistical Analysis | Multivariate statistics, trend analysis, spatial autocorrelation | Pattern detection, relationship testing, forecasting | Correlation coefficients, model parameters, significance values |

| Geospatial Analysis | GIS, landscape metrics, spatial interpolation | Landscape pattern quantification, spatial modeling | Land cover maps, fragmentation indices, connectivity networks |

| Meta-analysis | Systematic review, knowledge synthesis, gap identification | Research trend analysis, methodological comparison | Integration matrices, publication trends, citation networks |

| Indicator Validation | Sensitivity analysis, precision assessment, calibration | Indicator reliability testing, performance evaluation | Accuracy measures, uncertainty estimates, validation statistics |

Contemporary research increasingly employs scientometric methods using tools like CiteSpace and VOSviewer to analyze large publication datasets and identify research trends, knowledge gaps, and emerging foci [30]. These approaches enable researchers to transcend disciplinary boundaries and identify overarching patterns in ecological indicator development and application.

The historical evolution of ecological indicator development reveals a clear trajectory from reductionist approaches focused on single parameters toward increasingly integrated frameworks that acknowledge the multidimensional nature of environmental challenges. This evolution has been shaped by a dynamic interplay between scientific advances and regulatory needs, with each influencing the other in an iterative feedback loop.

Significant challenges remain in achieving truly comprehensive ecological assessments. The persistent integration gaps—particularly for socioeconomic, perceptual, and historical-cultural indicators—highlight the disciplinary boundaries that continue to constrain holistic environmental understanding [29]. Future indicator development must focus on bridging these conceptual and methodological divides while maintaining the scientific rigor necessary for effective environmental decision-making.

The ongoing refinement of frameworks like SUVA that integrate financial, environmental, and social dimensions represents a promising direction for sustainability assessment [31] [32]. As ecological indicators continue to evolve, their success will depend on their ability to serve as effective boundary objects that satisfy the informational requirements of both scientific inquiry and policy development while responding to emerging environmental challenges, particularly climate change [28] [30].

Assessment Methodologies: Implementing Ecological Indicator Evaluation Systems

The global rise in pharmaceutical consumption has led to increased detection of drug residues in diverse ecosystems, creating a critical need for robust environmental risk assessment (ERA) frameworks [33]. These pharmaceutical compounds, designed to be biologically active at low doses, can affect non-target organisms through conserved physiological pathways, posing potential risks to ecosystem health even at low environmental concentrations [33]. Regulatory agencies including the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) now mandate comprehensive Environmental Risk Assessments for new medicinal products, necessitating sophisticated multi-criteria decision analysis tools [34].

The entropy-weighted Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) method addresses key challenges in pharmaceutical ecosystem assessment by providing an objective, data-driven framework for evaluating multiple ecological indicators simultaneously. By integrating information-theoretic weighting with distance-based ranking, this approach reduces subjective bias in criterion importance assignment while effectively handling the complex, multi-dimensional nature of ecological risk parameters [35] [36]. This article examines the performance of entropy-weighted TOPSIS against alternative assessment methodologies within the broader context of ecological indicator evaluation research, providing researchers and drug development professionals with experimental protocols and comparative data for implementation in pharmaceutical environmental assessment programs.

Theoretical Foundations: Integrating Information Theory with Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis

Core Principles of Entropy-Weighted TOPSIS

The entropy-weighted TOPSIS model synthesizes two methodological approaches: information-theoretic weighting based on Shannon entropy and spatial aggregation through the TOPSIS ranking mechanism [36]. The fundamental premise is that criteria demonstrating greater variation across alternatives contain more information and should therefore receive higher objective weights in the decision model [35] [36]. This data-dispersion-based weighting reduces reliance on subjective judgment, enhancing the credibility of resulting rankings, particularly when dealing with complex ecological datasets where expert opinions on parameter importance may diverge [36].