Ensuring Data Integrity in Bio-Logging: A Comprehensive Guide to Verification and Validation Methods for Researchers

This article provides a systematic framework for the verification and validation of bio-logging data, a critical step for ensuring data integrity in animal-borne sensor studies.

Ensuring Data Integrity in Bio-Logging: A Comprehensive Guide to Verification and Validation Methods for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a systematic framework for the verification and validation of bio-logging data, a critical step for ensuring data integrity in animal-borne sensor studies. Covering foundational principles to advanced applications, it explores core data collection strategies like sampling and summarization, details simulation-based validation methodologies, and addresses prevalent challenges such as machine learning overfitting. A strong emphasis is placed on rigorous model validation protocols and the role of standardized data platforms. Designed for researchers and drug development professionals, this guide synthesizes current best practices to bolster the reliability of biologging data for ecological discovery, environmental monitoring, and biomedical research.

The Pillars of Trust: Understanding the Why and What of Bio-Logging Data Verification

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is validation so critical for bio-logging data? Bio-logging devices often use data collection strategies like sampling or summarization to overcome severe constraints in memory and battery life, which are imposed by the need to keep the logger's mass below 3-5% of an animal's body mass. However, these strategies mean that raw data is discarded in real-time and is unrecoverable. Validation ensures that the summarized or sampled data accurately reflects the original, raw sensor data and the actual animal behaviors of interest, preventing incorrect conclusions from undetected errors or data loss [1].

Q2: What are the most common data quality issues in sensor systems? A systematic review of sensor data quality identified that the most frequent types of errors are missing data and faults, which include outliers, bias, and drift in the sensor readings [2].

Q3: How can I detect and correct common sensor data errors? Research into sensor data quality has identified several common techniques for handling errors. The table below summarizes the predominant methods for error detection and correction, as found in a systematic review of the literature [2].

| Error Type | Primary Detection Methods | Primary Correction Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Faults (e.g., outliers, bias, drift) | Principal Component Analysis (PCA), Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) | PCA, ANN, Bayesian Networks |

| Missing Data | --- | Association Rule Mining |

Q4: What is the difference between synchronous and asynchronous sampling? Synchronous sampling records data in fixed, periodic bursts and may miss events that occur between these periods. Asynchronous sampling (or activity-based sampling) is more efficient; it only records when the sensor detects a movement or event of interest, thereby conserving more power and storage [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Validating Your Bio-logger Configuration

Problem: Uncertainty about whether a bio-logger is correctly configured to detect and record specific animal behaviors.

Solution: Employ a simulation-based validation methodology before deployment. This allows you to test and refine the logger's settings using recorded data where the "ground truth" is known [1].

Experimental Protocol:

- Data Collection: Use a high-capacity "validation logger" to record continuous, raw sensor data (e.g., accelerometer) from your subject animal. Simultaneously, collect synchronized, annotated video footage of the animal's behavior [1].

- Software-Assisted Analysis: Use tools like QValiData to manage the synchronization of video and sensor data. Annotate the video to label specific behaviors of interest [1].

- Simulation: In the software, run simulations of different bio-logger configurations (e.g., varying activity detection thresholds, sampling rates, or summarization algorithms) on the recorded raw sensor data [1].

- Evaluation: Compare the output of the simulated loggers against the annotated video ground truth. Quantify performance by calculating the percentage of missed events (false negatives) and falsely recorded events (false positives). Iterate the simulation until you find a configuration that reliably detects the target behaviors [1].

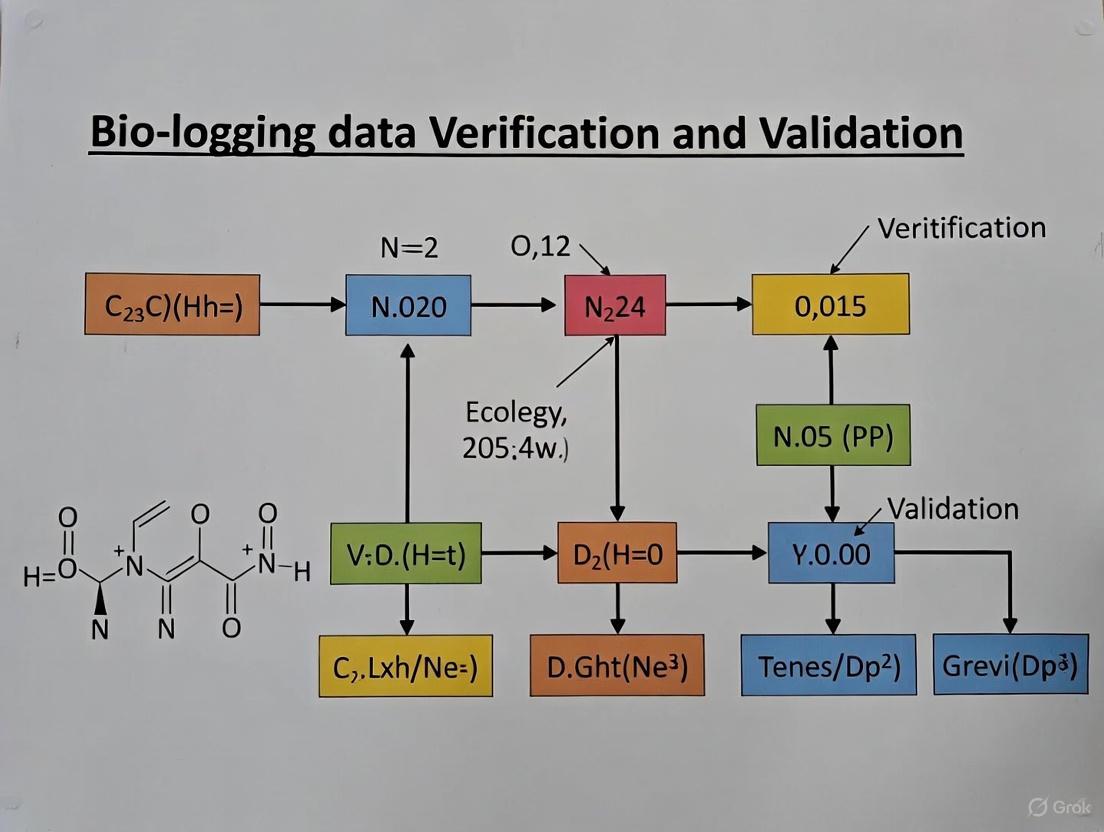

This workflow visualizes the protocol for validating a bio-logger's configuration:

Guide 2: Addressing Data Quality Errors

Problem: Sensor data streams contain errors such as outliers, drift, or missing data points.

Solution: Implement a systematic data quality control pipeline. The following workflow outlines the key stages for detecting and correcting common sensor data errors, based on established data science techniques [2].

Experimental Protocol for Data Quality Control:

- Error Detection:

- For faults (outliers, drift): Apply detection algorithms like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) or Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) to identify data points that deviate significantly from expected patterns [2].

- For missing data: Identify gaps and sequences in the data stream where values are absent [2].

- Error Correction:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key components and their functions in a bio-logging and data validation pipeline.

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Validation Logger | A custom-built bio-logger that records continuous, full-resolution sensor data at a high rate. It is used for short-duration validation experiments to capture the "ground truth" sensor signatures of behaviors [1]. |

| QValiData Software | A software application designed to synchronize video and sensor data, assist with video annotation and analysis, and run simulations of bio-logger configurations to validate data collection strategies [1]. |

| Data Quality Algorithms (PCA, ANN) | Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) are statistical and machine learning methods used to detect and correct faults (e.g., outliers, drift) in sensor data streams [2]. |

| Association Rule Mining | A data mining technique used to impute or fill in missing data points based on relationships and patterns discovered within the existing dataset [2]. |

| Darwin Core Standard | A standardized data format (e.g., using the movepub R package) used to publish and share bio-logging data, making it discoverable and usable through global biodiversity infrastructures like the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) [3]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

General Bio-logging Challenges

What are the primary constraints faced when designing bio-loggers? Bio-loggers are optimized under several strict constraints, primarily in this order: physical size, power consumption, memory capacity, and cost [4]. These constraints are interconnected; for instance, mass limitations directly restrict battery size and therefore the available energy budget for data collection and storage [1] [5].

How does the need for miniaturization impact data collection? To avoid influencing animal behavior, the total device mass must be minimized, often to 3-5% of an animal's body mass for birds [1]. This limits battery capacity and memory, which can preclude continuous high-speed recording of data [1]. Researchers must therefore employ data collection strategies like sampling and summarization to work within these energy and memory budgets [1].

What is the difference between bio-logging and bio-telemetry? Bio-logging involves attaching a data logger to an animal to record data for a period, which is then analyzed after logger retrieval. Bio-telemetry, in contrast, transmits data from the animal to a receiver in real-time. Bio-logging is particularly useful in environments where radio waves cannot reach, such as deep-sea or polar regions, or for long-term observation [6].

Data Management and Integrity

What are the best practices for managing memory and data structure on a bio-logger? Using a traditional file system on flash memory can be risky due to corruption if power fails during a write [4]. A more robust approach for multi-sensor data is to use a contiguous memory structure with inline, fixed-length headers [4]. Each data segment can consist of an 8-bit header (containing parity, mode, and type bits) followed by a 24-bit data record. This structure allows for data recovery even if the starting location is lost [4].

How can I efficiently record timestamps to save memory? Recording a full timestamp with every sample consumes significant memory. An efficient scheme uses a combination of absolute and relative time within a 32-bit segment [4]:

- Absolute Time: Uses 24 bits to record seconds since device start (covering ~194 days).

- Relative Time: Uses 24 bits to record milliseconds since the last Absolute Time was recorded (covering ~4.66 hours). A rule must be enforced that an Absolute Time record is made before the Relative Time counter overflows [4].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Insufficient Logger Deployment Duration

Symptoms: The bio-logger runs out of power or memory before the planned experiment concludes.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Excessively high data collection rate draining power and filling memory.

- Solution: Implement a data reduction strategy.

- Sampling: Record data in short bursts instead of continuously. Synchronous sampling occurs at fixed intervals, while asynchronous sampling triggers recording only when a movement of interest is detected, saving more resources [1].

- Summarization: Analyze data on-board the logger and store only extracted observations (e.g., activity counts, classified behaviors) instead of raw, high-resolution sensor data [1].

- Cause: Inefficient data formats and memory management.

- Solution: Optimize the data format in firmware. Use fixed-length data structures and efficient timestamping as described in the FAQs above to minimize storage overhead [4].

Problem: Validating Data from Non-Continuous Recording Strategies

Symptoms: Uncertainty about whether a sampling or summarization strategy correctly captures the animal's behavior, leading to concerns about data validity.

Solution: Employ a simulation-based validation procedure before final deployment [1].

Experimental Protocol for Validation [1]:

Data Collection for Simulation:

- Develop a "validation logger" that continuously records full-resolution, raw sensor data (e.g., accelerometer at high frequency) synchronized with video recordings of the animal in a controlled environment.

- The goal is to capture as many examples of relevant behaviors as possible.

Data Association and Annotation:

- Use software tools (e.g., QValiData) to synchronize the video and high-resolution sensor data.

- Annotate the video to label specific behaviors and link them to the corresponding raw sensor signatures.

Software Simulation:

- In software, run the recorded raw sensor data through simulated versions of your proposed bio-logger configurations (e.g., different sampling rates, activity detection thresholds, summarization algorithms).

- This allows for fast, repeatable testing of multiple configurations without deploying physical loggers.

Performance Evaluation:

- Compare the output of the simulated loggers against the ground truth from the video annotations.

- Evaluate the ability of each configuration to correctly detect and record the behaviors of interest. This helps fine-tune parameters for optimal sensitivity and selectivity.

Deployment:

- Apply the validated configuration from the simulation to loggers for the actual field experiment. This process increases confidence in the reliability of the data collected.

Problem: Handling and Analyzing Large, Complex Bio-logging Datasets

Symptoms: Difficulty in managing, exploring, and analyzing large, multi-sensor bio-logging datasets; slow processing and visualization.

Solutions and Best Practices:

- Data Reduction at Source: As a first step, critically evaluate and remove unused data [7].

- Remove Unused Columns: In your analysis software (e.g., Power BI, Python), drop any sensor channels or metadata columns not required for your specific research question [7].

- Filter Unneeded Rows: Limit data to relevant time periods or activity bouts. Avoid loading all historical data "just in case" [7].

Leverage Efficient Data Technologies:

- In-Memory Databases: Use in-memory databases (e.g., Memgraph, Redis) for data exploration and analysis. They store data in RAM, providing nanosecond to microsecond query response times and enabling real-time analytics on large datasets [8].

- Aggregations: For interactive dashboards, create pre-summarized tables (e.g., activity counts per hour). The system can then use these small, fast tables for high-level queries, only accessing the full dataset when drilling into details [7].

Adopt Advanced Visualization and Multi-Disciplinary Collaboration:

Technical Reference

Comparison of Data Collection Strategies

| Strategy | Description | Pros | Cons | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous Recording | Stores all raw, full-resolution sensor data. | Complete data fidelity. | High power and memory consumption; limited deployment duration [1]. | Short-term studies requiring full dynamics. |

| Synchronous Sampling | Records data in fixed-interval bursts. | Simple to implement. | May miss events between bursts; records inactive periods [1]. | Periodic behavior patterns. |

| Asynchronous Sampling | Triggers recording only upon detecting activity of interest. | Efficient use of resources; targets specific events. | Loss of behavioral context between events; requires robust activity detector [1]. | Capturing specific, discrete movement bouts. |

| Summarization | On-board analysis extracts and stores summary metrics or behavior counts. | Maximizes deployment duration; provides long-term trends. | Loss of raw signal dynamics; limited to pre-defined metrics [1]. | Long-term activity budgeting and ethogram studies. |

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Validation Logger | A custom-built logger that sacrifices deployment duration to continuously record full-resolution, raw sensor data for the purpose of validating other data collection strategies [1]. |

| Synchronized Video System | High-speed video equipment synchronized with the validation logger's clock, providing ground truth for associating sensor data with specific animal behaviors [1]. |

| Software Simulation Tool (e.g., QValiData) | A software application used to manage synchronized video and sensor data, annotate behaviors, and run simulations of various bio-logger configurations to validate their performance [1]. |

| In-Memory Database (e.g., Memgraph, Redis) | A database that relies on main memory (RAM) for data storage, enabling extremely fast data querying, exploration, and analysis of large bio-logging datasets [8]. |

Workflow Diagrams

Figure 1: Strategy Selection & Validation Workflow

Figure 2: Simulation-Based Validation Protocol

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is my sampled bio-logging data not representative of the entire animal population? This is often due to sampling bias. The methodology below outlines a stratified random sampling protocol designed to capture population diversity.

Q2: How do I choose between storing raw data samples or summary statistics for long-term studies? The choice involves a trade-off between storage costs and informational fidelity. For critical validation work, storing raw samples is recommended. The workflow diagram below illustrates this decision process.

Q3: What steps can I take to verify the integrity of summarized data (e.g., mean, max) against its original raw data source? Implement a automated reconciliation check. A protocol for this is provided in the experimental protocols section.

Q4: My data visualization is unclear to colleagues. How can I make my charts more accessible? Avoid red/green color combinations and ensure high color contrast. Use direct labels instead of just a color legend, and consider using patterns or shapes in addition to color. The diagrams in this guide adhere to these principles [9] [10] [11].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Stratified Random Sampling for Bio-Logging Data

Objective: To collect a representative sample of bio-logging data from a heterogeneous animal population across different regions and age groups.

Materials: Bio-loggers, GPS tracker, data storage unit, analysis software (e.g., R, Python).

Methodology:

- Define Strata: Divide the total animal population into non-overlapping subgroups (strata) based on key characteristics relevant to the research (e.g., species, age, geographic region).

- Determine Sample Size: Calculate a sample size for each stratum. This can be proportional to the stratum's size in the population or allocated to ensure sufficient representation of smaller subgroups.

- Random Sampling: Within each stratum, randomly select individual animals for bio-logger deployment using a random number generator.

- Data Collection: Deploy bio-loggers and collect time-series data for the desired parameters (e.g., heart rate, temperature, location).

- Data Validation: Perform initial data quality checks to identify and remove corrupted data files.

Protocol 2: Data Summarization and Integrity Verification

Objective: To generate summary statistics from raw bio-logging data and verify their accuracy against the source data.

Materials: Raw time-series data set, statistical computing software (e.g., R, Python with pandas).

Methodology:

- Data Preprocessing: Clean the raw data by handling missing values (e.g., via interpolation) and removing outliers based on pre-defined physiological thresholds.

- Summarization: Calculate summary statistics for defined epochs (e.g., hourly, daily). Key statistics include:

- Central Tendency: Mean, Median

- Dispersion: Standard Deviation, Range (Min, Max)

- Other: 95th Percentile

- Integrity Verification (Reconciliation):

- From the original raw data, manually re-calculate one or more of the summary statistics for a randomly selected epoch.

- Compare your manually calculated values with the previously generated summary statistics.

- The results should match exactly. Any discrepancy indicates an error in the summarization algorithm that must be investigated and corrected.

Visual Guides

Data Strategy Selection Workflow

This diagram outlines the decision process for choosing between continuous sampling and data summarization in bio-logging studies [12].

Data Verification Process

This flowchart details the steps for verifying the integrity of summarized data against raw source data [12].

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Bio-loggers | Miniaturized electronic devices attached to animals to record physiological and environmental data (e.g., temperature, acceleration, heart rate) over time. |

| GPS Tracking Unit | Provides precise location data, enabling the correlation of physiological data with geographic position and movement patterns. |

| Data Storage Unit | Onboard memory for storing recorded data. Selection involves a trade-off between capacity, power consumption, and reliability. |

| Statistical Software (R/Python) | Open-source programming environments used for data cleaning, statistical summarization, and the creation of reproducible analysis scripts. |

The Critical Role of Metadata and Standardized Platforms (e.g., BiP, Movebank)

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

| Question | Answer |

|---|---|

| What is the primary purpose of standardized biologging platforms like BiP and Movebank? | They enable collaborative research and biological conservation by storing, standardizing, and sharing complex animal-borne sensor data and associated metadata, ensuring data preservation and facilitating reuse across diverse fields like ecology, oceanography, and meteorology [13]. |

| Why is detailed metadata so critical for biologging data? | Sensor data alone is insufficient. When linked with metadata about animal traits (e.g., sex, body size), instrument details, and deployment information, it becomes a meaningful dataset that allows researchers to explore questions about individual differences in behavior and migration [13]. |

| My data upload to a platform failed. What could be the cause? | A common cause is a data structure issue. When using reference data, selecting "all Movebank attributes" can introduce unexpected columns, data type mismatches, or a data volume that overwhelms the system. It is often best to select only the attributes relevant to your specific study [14]. |

| How does Movebank ensure the long-term preservation of my published data? | The Movebank Data Repository is dedicated to long-term archiving, storing data in consistent, open formats. It follows a formal preservation policy and guarantees storage for a minimum of 10 years, with backups in multiple locations to ensure data integrity and security [15]. |

| Can biologging data really contribute to fields outside of biology? | Yes. Animals carrying sensors can collect high-resolution environmental data like water temperature, salinity, and ocean winds from areas difficult to access by traditional methods like satellites or Argo floats, making them valuable for oceanography and climate science [13] [16]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Resolving Data Upload and Integration Errors

Problem: You encounter an error when trying to upload data or use functions like add_resource() with a reference table.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

- Cause: Excessive or Incompatible Attributes

- Solution: Be selective with attributes. Instead of downloading "all Movebank attributes," choose only the ones currently in your study or directly relevant to your analysis. This minimizes conflicts related to unexpected columns or data structures [14].

- Cause: Data Quality and Structure Issues

- Solution: Perform data wrangling before upload.

- Cause: System Overload from Large Data Volume

- Solution: If you must use a very large dataset, consider chunking. Break your data into smaller pieces, process each separately, and then combine the results [14].

Guide 2: Designing a Robust Biologging Study for Data Validation

Problem: Ensuring the data you collect is fit for purpose and can be reliably validated for your research.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

- Challenge: Ensuring Data Reproducibility

- Solution: Adopt a standardized metadata framework. Platforms like BiP use international standards (e.g., ITIS, CF Conventions) for metadata. Faithfully completing all required metadata fields during upload—including individual animal traits, device specifications, and deployment details—is crucial for the long-term usability and validation of your data [13].

- Challenge: Detecting Critical Life Events

- Solution: Integrate multiple sensor types to infer events like mortality or reproduction.

- Survival: Use a combination of GPS tracking, accelerometers, and temperature loggers to reliably identify mortality events and their potential causes [16].

- Reproduction: Identify breeding behavior and success through recursive movement patterns (e.g., central-place foraging) from GPS data, validated by accelerometer data or direct observation [16].

- Solution: Integrate multiple sensor types to infer events like mortality or reproduction.

Platform Comparison and Data Standards

Table 1: Key Features of Biologging Data Platforms

| Feature | Biologging intelligent Platform (BiP) | Movebank Data Repository |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Standardization and analysis of diverse sensor data types [13]. | Publication and long-term archiving of animal tracking data [15]. |

| Unique Strength | Integrated Online Analytical Processing (OLAP) tools to estimate environmental and behavioral parameters from sensor data [13]. | Strong emphasis on data preservation, following the OAIS reference model and FAIR principles [15]. |

| Metadata Standard | International standards (ITIS, CF, ACDD, ISO) [13]. | Movebank's own published vocabulary and standards [15]. |

| Data Licensing | Open data available under CC BY 4.0 license [13]. | Persistently archived and publicly available; specific license may vary by dataset. |

Table 2: Essential Metadata for Biologging Data Verification

| Metadata Category | Key Elements | Importance for Verification & Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Animal Traits | Species, sex, body size, breeding status [13]. | Allows assessment of individual variation and controls for biological confounding factors. |

| Device Specifications | Sensor types (GPS, accelerometer), manufacturer, accuracy, sampling frequency [13]. | Critical for understanding data limitations, precision, and potential sources of error. |

| Deployment Information | Deployment date/location, attachment method, retrievers [13]. | Provides context for the data collection event and allows assessment of potential human impact on the animal's behavior. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Biologging Research

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Satellite Relay Data Loggers (SRDL) | Transmit compressed data (e.g., dive profiles, temperature) via satellite, enabling long-term, remote data collection without recapturing the animal [13]. |

| GPS Loggers | Provide high-resolution horizontal position data, the foundation for studying animal movement, distribution, and migration routes [13] [16]. |

| Accelerometers | Measure 3-dimensional body acceleration, used to infer animal behavior (e.g., foraging, running), energy expenditure, and posture [16]. |

| Animal-Borne Ocean Sensors | Measure environmental parameters like water temperature, salinity, and pressure, contributing to oceanographic models [13]. |

Experimental Workflow for Biologging Data Collection and Validation

The following diagram illustrates a generalized experimental protocol for a biologging study, from planning to data sharing, highlighting key steps for ensuring data validity.

Identifying Global Biases and Gaps in Bio-Logging Data Collection

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most common sources of bias in bio-logging data? Bio-logging data can be skewed by several factors. Taxonomic bias arises from a focus on charismatic or easily trackable species, while geographical bias occurs when data is collected predominantly from accessible areas, leaving remote or politically unstable regions underrepresented [17]. Furthermore, size bias is prevalent, as smaller-bodied animals cannot carry larger, multi-sensor tags, limiting the data collected from these species [5].

Q2: How can I verify the quality of my accelerometer data before analysis? Initial verification should check for sensor malfunctions and data integrity. Follow this workflow to diagnose common issues:

Q3: What does data validation mean in the context of a bio-logging study? Validation ensures your data is fit for purpose and its quality is documented. It involves evaluating results against pre-defined quality specifications from your Quality Assurance Project Plan (QAPP), including checks on precision, accuracy, and detection limits [18]. For behavioral classification, this means validating inferred behaviors (e.g., "foraging") against direct observations or video recordings [5]. It is distinct from verification, which is the initial check for accuracy in species identification and data entry [19].

Q4: Our multi-sensor tag data is inconsistent. How do we troubleshoot this? Multi-sensor approaches are a frontier in bio-logging but can present integration challenges [5]. Begin with the following diagnostic table.

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Troubleshooting Action |

|---|---|---|

| Conflicting behavioral classifications (e.g., GPS says "stationary" but accelerometer says "active") | Sensors operating at different temporal resolutions or clock drift. | Re-synchronize all sensor data streams to a unified timestamps and interpolate to a common time scale. |

| Drastic, unexplainable location jumps in dead-reckoning paths. | Incorrect speed calibration or unaccounted-for environmental forces (e.g., currents, wind). | Re-calibrate the speed-to-acceleration relationship and incorporate environmental data (e.g., ocean current models) into the path reconstruction [5]. |

| Systematic failure of one sensor type across multiple tags. | Manufacturing fault in sensor batch or incorrect firmware settings. | Check and update tag firmware. Test a subset of tags in a controlled environment before full deployment. |

Q5: Why is data standardization critical for addressing global data gaps? Heterogeneous data formats and a lack of universal protocols prevent the integration of datasets from different research groups [17]. This lack of integration directly fuels global data gaps, as it makes comprehensive, large-scale analyses impossible. Adopting standard vocabularies and transfer protocols allows data to be aggregated, enabling a true global view of animal movement and revealing macro-ecological patterns that are invisible at the single-study level [17] [20].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Correcting Spatial Biases in Your Dataset

Spatial biases can undermine the ecological conclusions of your study. This protocol helps identify and mitigate them.

Objective: To identify over- and under-represented geographical areas in a bio-logging dataset and outline strategies for correction.

Required Materials:

- Your animal tracking dataset (e.g., GPS fixes).

- GIS software (e.g., QGIS, ArcGIS).

- Environmental and human impact layers (e.g., human footprint index, land cover, protected area maps).

Methodology:

- Data Compilation: Compile all animal location fixes into your GIS software.

- Create Utilization Distributions: Generate a utilization distribution (UD) or heat map from the location data. This represents the "used" habitat.

- Define the "Available" Area: Define a study area representing the "available" habitat (e.g., a minimum convex polygon around all points plus a buffer).

- Sampling Intensity Map: Create a grid over the study area and count the number of location fixes in each cell. Compare this to a random or systematic sample of points within the "available" area.

- Statistical Comparison: Use a statistical test like Chi-square to compare the distribution of fixes against the expected distribution if sampling were even.

- Correlation with Covariates: Overlay the sampling bias map with environmental covariate layers to understand what factors (e.g., distance to roads, elevation) are correlated with the bias.

Interpretation and Correction:

- Identification: The analysis will reveal "cold spots" (areas with fewer data points than expected) and "hot spots" (areas with more).

- Reporting: Always report these biases and the extent of your study area in your methods. Do not extrapolate conclusions to underrepresented areas.

- Model Correction: In subsequent analyses (e.g., species distribution models), incorporate the sampling bias map as a bias layer to correct the model's output.

Guide 2: A Protocol for Multi-Sensor Data Verification and Fusion

Integrating data from accelerometers, magnetometers, GPS, and environmental sensors is complex. This workflow ensures data coherence before fusion.

Objective: To verify the integrity of individual sensor data streams and ensure their temporal alignment for a multi-sensor bio-logging tag.

Experimental Protocol:

- Pre-deployment Bench Test:

- Simultaneously record data from all sensors in a controlled, static position and during known movements (e.g., precise rotations, simulated flapping).

- Verify that sensor outputs are physically plausible and synchronized.

- Temporal Synchronization:

- Action: Identify a common, high-frequency timestamp source (e.g., the accelerometer's clock). Re-sample or interpolate all other sensor data streams (e.g., lower-frequency GPS) to this master timeline.

- Check: Look for temporal drifts between sensors by examining the timing of sharp, discrete events captured by multiple sensors.

- Physical Plausibility Check:

- GPS vs. Dead-reckoning: Compare the track reconstructed from dead-reckoning (using accelerometer, magnetometer, and pressure sensor data) with the occasional GPS fixes. Large, consistent discrepancies indicate a calibration error in speed or heading [5].

- Behavioral Classification Consistency: Ensure that behaviors classified from accelerometer data (e.g., "feeding") are spatially coherent with GPS data (e.g., occurring in known foraging grounds).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Bio-Logging Research |

|---|---|

| Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) | A sensor package, often including accelerometers, gyroscopes, and magnetometers, that measures an animal's specific force, angular rate, and orientation [5]. |

| Data Logging Platforms (e.g., Movebank) | Online platforms that facilitate the management, sharing, visualization, and archival of animal tracking data, crucial for data standardization and collaboration [17]. |

| Tri-axial Accelerometer | Measures acceleration in three spatial dimensions, allowing researchers to infer animal behavior (e.g., foraging, running, flying), energy expenditure, and biomechanics [5]. |

| Quality Assurance Project Plan (QAPP) | A formal document outlining the quality assurance and quality control procedures for a project. It is critical for defining data validation criteria and ensuring data reliability [18]. |

| Animal-Borne Video Cameras | Provides direct, ground-truthed observation of animal behavior and environment, which is essential for validating behaviors inferred from other sensor data like accelerometry [5]. |

| Bio-Logging Data Standards | Standardized vocabularies and transfer protocols (e.g., as developed by the International Bio-Logging Society) that enable data integration across studies and institutions [17] [20]. |

From Theory to Practice: Implementing Robust Data Collection and Validation Workflows

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core purpose of simulation-based validation for bio-loggers? Simulation-based validation allows researchers to test and validate different bio-logger data collection strategies (like sampling and summarization) in software before deploying them on animals. This process uses previously recorded "raw" sensor data and synchronized video to determine how well a proposed logging configuration can detect specific behaviors, ensuring the chosen parameters will work correctly in the field. This saves time and resources compared to conducting multiple live animal trials [1].

Q2: My bio-logger has limited memory and battery. What data collection strategies can I simulate with this method? You can primarily simulate and compare two common strategies:

- Sampling: Recording full-resolution data only at specific intervals (synchronous) or when activity is detected (asynchronous) [1].

- Summarization: On-board analysis of sensor data where only key summaries (e.g., activity counts, detected behavior classifications) are stored instead of the raw data stream [1].

Q3: What are the minimum data requirements for performing a simulation-based validation study? You need two synchronized data sources:

- Continuous, high-resolution sensor data from a "validation logger" deployed on the animal.

- Synchronized and annotated video recordings of the animal's behavior during the data collection period [1]. This combination allows you to correlate sensor signatures with specific, known behaviors.

Q4: During video annotation, what should I do if a behavior is ambiguous or difficult to classify? Consult with multiple observers to reach a consensus. The QValiData software includes features to assist with video analysis and annotation. Ensuring accurate and consistent behavioral labels is critical for training reliable models, so ambiguous periods should be clearly marked and potentially excluded from initial training sets [1].

Q5: After simulation, how do I know if my logger configuration is "good enough"? Performance is typically measured by comparing the behaviors detected by the simulated logger against the ground-truth behaviors from the video. Key metrics include:

- High agreement (e.g., >80%) in behavioral classifications between the simulation and video [21].

- Minimal difference in derived metrics like energy expenditure when using the simulated data versus raw data [21].

- Satisfactory performance across all behaviors of interest, not just the most common ones.

Troubleshooting Guide

Configuration and Setup

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Software (QValiData) fails to load or run. | Missing dependencies or incorrect installation. | Ensure all required libraries (Qt 5, OpenCV, qcustomplot, Iir1) are installed and correctly linked [22]. |

| Video and sensor data cannot be synchronized. | Improperly created or missing synchronization timestamps. | Implement a clear start/stop synchronization event at the beginning and end of data collection that is visible in both the video and sensor data log. |

| Simulated logger misses a specific behavior. | Activity detection threshold is set too high, or the sensor sample rate is too low. | In the simulation software, lower the detection threshold for the specific axis associated with the behavior and ensure the simulated sampling rate is sufficient to capture the behavior's dynamics. |

Data Analysis and Validation

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low agreement between simulated logger output and video observations. | The model was trained on data that lacks individual behavioral variability, leading to poor generalization [21]. | Ensure your training dataset incorporates data from multiple individuals and trials to capture natural behavioral variations. Integrate both unsupervised and supervised machine learning approaches to better account for this variability [21]. |

| High false positive rate for activity detection. | Activity detection threshold is set too low, classifying minor movements or noise as significant activity. | Re-calibrate the detection threshold using the simulation software, increasing it slightly. Validate against video to confirm the change reduces false positives without missing true events. |

| Classifier confuses two specific behaviors (e.g., "swimming" and "walking"). | The sensor signals for the two behaviors are very similar, or the features used for classification are not discriminatory enough [21]. | Review the raw sensor signatures for the confused behaviors. Use feature engineering to find more distinctive variables (e.g., spectral features, variance over different windows). In the model, provide more labeled examples of both behaviors. |

| Large discrepancy in energy expenditure (DEE) estimates. | This is often a consequence of misclassified behaviors, as different activities are assigned different energy costs [21]. | Focus on improving the behavioral classification accuracy, particularly for high-energy behaviors. Validate your Dynamic Body Acceleration (DBA) to energy conversion factors with independent measures if possible. |

Experimental Protocol: Simulation-Based Validation for Activity Loggers

The following workflow, adapted from bio-logging research, provides a methodology for validating activity logger configurations [1].

Phase 1: Data Collection

- Objective: Capture synchronized, high-resolution sensor data and video of the animal performing behaviors of interest.

- Materials:

- Validation Logger: A custom data logger capable of continuous, high-rate recording of sensors (e.g., accelerometer). Runtime is sacrificed for data resolution [1].

- Video Recording System: High-frame-rate cameras.

- Synchronization Method: A clear, simultaneous start/stop signal (e.g., a visual marker and a corresponding sharp movement of the logger).

- Procedure:

- Deploy the validation logger on the animal (e.g., a captive bird like the Dark-eyed Junco).

- Start video recording and generate the synchronization event.

- Record the animal's activity for a sufficient duration to capture multiple instances of all behaviors of interest.

- End the session with another synchronization event.

Phase 2: Data Processing and Annotation

- Objective: Create a ground-truthed dataset for simulation.

- Procedure:

- Synchronize: Use software (e.g., QValiData) to align the video and sensor data streams based on the recorded start/stop events [1].

- Annotate Video: Carefully watch the synchronized video and label the timing and type of each behavior performed. This creates the "truth" dataset.

- Process Sensor Data: If necessary, apply basic filtering or calculate common metrics (e.g., Vectorial Dynamic Body Acceleration - VeDBA, pitch, roll) from the raw sensor data [1] [21].

Phase 3: Simulation and Validation

- Objective: Test different bio-logger configurations in software and evaluate their performance.

- Procedure:

- Define Configuration: In the simulation tool, set the parameters you wish to test (e.g., sampling rate, activity detection threshold, summarization algorithm).

- Run Simulation: The software processes the recorded raw sensor data as if it were being collected by a logger with your specified configuration [1].

- Compare and Validate: The simulation output (e.g., detected activity periods, classified behaviors) is compared against the annotated behaviors from the video.

- Quantify Performance: Calculate agreement metrics (e.g., percentage accuracy, F1-score) and compare derived quantities like energy expenditure [21].

- Iterate: If performance is unsatisfactory, adjust the configuration parameters and repeat the simulation until optimal performance is achieved.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials and Tools

The following table lists key components for establishing a simulation-based validation pipeline.

| Item Name | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| Validation Logger | A custom-built data logger designed for continuous, high-resolution data capture from sensors like accelerometers. It serves as the source of "ground-truth" sensor data [1]. |

| Synchronized Video System | High-speed cameras used to record animal behavior. The video provides the independent, ground-truthed behavioral labels needed for validation [1]. |

| QValiData Software | A specialized software application designed to facilitate validation studies. It assists with synchronizing video and data, video annotation and magnification, and running bio-logger simulations [1] [22]. |

| Machine Learning Libraries (e.g., for Random Forest, EM) | Software libraries that implement algorithms for classifying animal behaviors from sensor data. Unsupervised methods (e.g., Expectation Maximization) can detect behaviors, while supervised methods (e.g., Random Forest) can automate classification on new data [21]. |

| Data Analysis Environment (e.g., R, Python) | A programming environment used for feature extraction, signal processing, statistical analysis, and calculating performance metrics and energy expenditure (e.g., DBA) [21]. |

This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs on data sampling strategies, specifically synchronous versus asynchronous methods, framed within broader research on bio-logging data verification and validation. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, selecting the appropriate data capture strategy is crucial for balancing data integrity with the power, memory, and endurance constraints inherent in long-term biological monitoring [1]. This resource directly addresses specific issues you might encounter during your experiments.

FAQs: Understanding Sampling Methods

What is the fundamental difference between synchronous and asynchronous sampling?

Synchronous Sampling is a clock-driven method where data is captured at fixed, regular time intervals, known as the Nyquist rate or higher [23]. It is a periodic process, meaning the system samples the signal regardless of whether the signal's amplitude has changed.

Asynchronous Sampling is an event-driven method. Also known as level-crossing sampling or asynchronous delta modulation, it captures a data point only when the input signal crosses a predefined amplitude threshold [23]. Its operation is not governed by a fixed clock but by the signal's activity, making it non-periodic.

When should I use asynchronous sampling in bio-logging applications?

Asynchronous sampling is particularly advantageous in scenarios involving sparse or burst-like signals, which are common in neural activity or other bio-potential recordings [23]. Its key benefits for bio-logging include:

- Data Compression: It inherently reduces data size by ignoring periods of signal inactivity, which is critical for memory-constrained long-term deployments [23] [1].

- Power Efficiency: By minimizing unnecessary sampling and conversion operations, it reduces power consumption, helping to adhere to strict mass and energy budgets for implantable or animal-borne devices [23] [1].

- Activity-Dependent Dissipation: The system's power usage scales with signal activity, preserving energy during quiet periods [23].

What are the main drawbacks of asynchronous sampling I should be aware of?

While powerful, asynchronous sampling has limitations that must be considered during experimental design:

- Complex Signal Reconstruction: Rebuilding the original signal from event-based data is more complex than with uniformly sampled data [23].

- Potential for Signal Loss: In "fixed window" implementations, finite loop delay times during reset periods can cause small portions of the signal to be lost, potentially leading to distortion [23].

- Limited Resolution: The method trades simplicity and power for resolution, making it generally less suitable for very high-resolution applications (>8 bits) compared to some synchronous methods [23].

- Design Complexity: The circuit and logic required for activity detection and level-crossing are more complex than a simple clocked sampler [23].

Synchronous sampling can place significant demands on system resources, which is a primary challenge in large-scale or long-duration bio-logging studies [1].

- Power Consumption: Constantly sampling at a fixed high rate requires continuous operation of the analog-to-digital converter (ADC) and other circuitry, leading to high power dissipation [23].

- Memory and Storage: Recording all data points, including periods of no activity, generates large data volumes that can quickly fill available storage [1].

- Data Transmission: The high, constant data rate demands a high-bandwidth (and high-power) wireless transmission link, which is a major power bottleneck in sensor arrays [23].

What is the difference between simultaneous and multiplexed sampling?

These are two hardware architectures for multi-channel synchronous sampling.

- Simultaneous Sampling: Each input channel has its own dedicated ADC. All channels are sampled at exactly the same instant, providing no phase delay between channels. This allows for direct comparison of acquired values and is ideal for measuring precise timing relationships between signals [24].

- Multiplexed Sampling: A single ADC is shared across multiple input channels using a multiplexer. The channels are scanned one after another, resulting in a small phase delay (skew) between channels. The maximum sampling rate per channel is the system's total sampling rate divided by the number of active channels [24].

The table below summarizes these hardware considerations.

Table 1: Comparison of Simultaneous and Multiplexed Sampling Architectures

| Feature | Simultaneous Sampling | Multiplexed Sampling |

|---|---|---|

| ADC per Channel | Yes, each channel has a dedicated ADC | No, a single ADC is shared across all channels |

| Phase Delay | No phase delay between channels | Phase delay exists between scanned channels |

| Sampling Rate | Full rate on every channel, independently | Max rate per channel = Total Rate / Number of Channels |

| Crosstalk | Lower, due to independent input amplifiers | Higher, as signals pass through the same active components |

| Cost & Complexity | Higher | Lower |

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Excessive Data Volume in Long-Term Experiments

Problem: Your bio-logger is running out of memory before the experiment concludes, risking the loss of critical data.

Solution Steps:

- Analyze Signal Characteristics: Review preliminary data to identify the sparsity of your signal of interest. If the signal has long inactive periods, asynchronous sampling may be a solution [23] [1].

- Switch to Asynchronous Sampling: If your hardware supports it, configure the logger for asynchronous, event-driven sampling. This will capture data only during biologically relevant events, drastically reducing total data volume [1].

- Implement Data Summarization: If continuous recording is mandatory, consider on-board data summarization. Instead of storing raw data, the logger can process data to extract and store summary statistics (e.g., activity counts, frequency domain features) at set intervals [1].

- Adjust Synchronous Sampling Rate: If you must use synchronous sampling, verify that your sampling rate is not unnecessarily high. Ensure it meets the Nyquist criterion for your signal's highest frequency of interest but is not excessively beyond it.

Issue: Poor Battery Life in Deployed Loggers

Problem: The battery in your animal-borne or implantable data logger depletes faster than expected.

Solution Steps:

- Profile Power Usage: Identify the main power consumers. In synchronous systems, the ADC and radio for data transmission are often the most power-hungry components [23].

- Optimize Sampling Strategy:

- Adopt Asynchronous Sampling: This is one of the most effective steps. An activity-dependent system consumes significantly less power during signal inactivity [23].

- Reduce Synchronous Sampling Rate: Lowering the fixed sampling rate reduces the duty cycle of the ADC and processor.

- Optimize Data Transmission: If your logger transmits data wirelessly, this is a major power sink. Use the data compression benefits of asynchronous sampling to reduce the amount of data that needs to be transmitted [23].

Issue: Signal Distortion or Loss in Asynchronous Sampling

Problem: The signal reconstructed from your asynchronous sampler appears distorted or has a DC offset.

Solution Steps:

- Check Loop Delay: This is a common issue in "fixed window" level-crossing ADCs. The finite time required to reset the circuit after a threshold crossing can cause small portions of the signal to be lost [23]. The accumulated error can be modeled as: ( E = 2NA((T{loop} + T{delay}) / T{signal}) + \frac{2}{3}\pi A f{input} f{clock} ) where ( T{loop} ) and ( T{delay} ) are the loop and comparator propagation delays, and ( T{signal} ) is the signal's rise time [23].

- Validate Threshold Levels: Ensure the amplitude thresholds for level-crossing are appropriate for your signal's dynamic range. Thresholds set too wide can miss fine details, while thresholds too narrow can generate excessive, noisy data.

- Verify Comparator Performance: Ensure the comparators have a sufficiently fast response time (low ( T_{delay} )) to accurately detect threshold crossings for your signal's frequency.

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Protocol: Validating an Asynchronous Sampling Bio-Logger

Objective: To determine the accuracy and efficiency of an asynchronous bio-logger in detecting and recording specific animal behaviors.

Background: Validating on-board activity detection is crucial, as unrecorded data are unrecoverable. This protocol uses synchronized video as a ground truth [1].

Materials:

- Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Item Function Validation Logger A custom logger that continuously records full-resolution, synchronous sensor data at a high rate, used as a reference [1]. Production Logger The asynchronous bio-logger under test, configured with the candidate activity detection parameters. Synchronized Camera Provides video ground truth for behavior annotation. Data Analysis Software (e.g., QValiData) Software to manage, synchronize, and analyze sensor data with video [1].

Methodology:

- Data Collection: Securely attach both the validation logger and the production logger to the animal subject (e.g., a small bird like the Dark-eyed Junco). Record synchronized, high-frame-rate video of the animal's behavior in a controlled or naturalistic setting [1].

- Video Annotation: Carefully review the video footage and annotate the precise start and end times of all occurrences of the target behaviors.

- Data Synchronization: Use software like QValiData to synchronize the video timeline with the sensor data timelines from both loggers.

- Simulation and Analysis: Using the continuous data from the validation logger, run software simulations of the production logger's asynchronous sampling algorithm. Compare the events detected by the simulator (and the actual production logger) against the annotated video ground truth.

- Parameter Tuning: Calculate performance metrics (e.g., detection sensitivity, false-positive rate). Iteratively adjust the activity detection parameters (e.g., threshold levels, timing windows) in the simulation and repeat the analysis until optimal performance is achieved [1].

The workflow for this validation protocol is illustrated below.

Decision Framework for Sampling Strategy

The following diagram provides a logical workflow for choosing between synchronous and asynchronous sampling based on your experimental needs.

Leveraging Unsupervised Learning and AI for Rare Behavior Detection

Technical Support Center

Core Concepts: Anomaly Detection in Bio-Logging

What is the fundamental principle behind using unsupervised learning for rare behavior detection?

Unsupervised learning identifies rare behaviors by detecting outliers or deviations from established normal patterns without requiring pre-labeled examples of the rare events. This is crucial in bio-logging, where labeled data for rare behaviors is often scarce or non-existent. The system learns a baseline of "normal" behavioral patterns from the collected data and then flags significant deviations as potential rare behaviors [25] [26]. For instance, in animal motion studies, this involves capturing the spatiotemporal dynamics of posture and movement to identify underlying latent states that represent behavioral motifs [27].

How does this approach differ from supervised methods?

Unlike supervised learning that requires a fully labeled dataset with known anomalies for training, unsupervised techniques do not need any labeled data. This makes them uniquely suited for discovering previously unknown or unexpected rare behaviors that researchers may not have envisaged in advance [28] [26].

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: My model suffers from high false positive rates, flagging normal behavioral variations as anomalies. How can I improve precision?

- Problem: High false positive rates often occur when the model's concept of "normal" is too narrow or the anomaly threshold is too sensitive.

- Solution:

- Refine the "Normal" Dataset: Ensure your training data is as pure as possible. Manually review and curate the data used to establish the baseline to remove any undetected anomalies [29].

- Feature Engineering: Re-evaluate the features extracted from your raw sensor data. Incorporate more temporal or context-aware features that better capture the essence of the behavior beyond simple movement statistics [28].

- Adjust Thresholds: Implement adaptive thresholding mechanisms. Instead of a fixed value, use a percentile-based approach on the normal data's reconstruction error or anomaly score distribution [29].

- Model Selection: Consider using an Isolation Forest algorithm. It is particularly effective for isolating anomalies and often results in lower false positives in high-dimensional data [28] [26].

FAQ 2: The bio-logger's battery depletes quickly before capturing any rare events. How can I optimize power consumption?

- Problem: Continuous operation of high-cost sensors (like video cameras) drains the battery, leaving insufficient power for long-term observation.

- Solution: Implement a tiered sensing strategy.

- Always-On Low-Cost Sensors: Use low-power sensors (e.g., accelerometers, depth sensors) to continuously monitor behavior [28].

- On-Device AI Trigger: Run a lightweight, on-board anomaly detection model on the data from the low-cost sensors. This model should be distilled from a larger, more complex model to be both efficient and effective [28].

- Conditional Activation: Program the bio-logger to activate the high-power sensors (e.g., video camera) only when the on-board model detects a potential outlier. This ensures power is reserved for capturing the events of interest [28].

FAQ 3: How can I validate that the "anomalies" detected by the model are biologically meaningful behaviors and not just sensor noise or artifacts?

- Problem: It is challenging to distinguish between true behavioral anomalies and data corruption.

- Solution:

- Cross-Referencing with Video: This is the most direct method. Use the timestamps of detected anomalies to review corresponding video recordings, if available, to visually confirm the behavior [28].

- Data Preprocessing and Filtering: Apply robust data cleaning pipelines to raw sensor data before feature extraction to remove common noise artifacts [29].

- Cluster Analysis: Perform clustering on the detected anomalies. True behaviors will often form coherent clusters in the latent space, while random noise will not. Tools like VAME (Variational Animal Motion Embedding) can segment continuous latent space into discrete, meaningful behavioral motifs [27].

- Statistical Significance Testing: Analyze the frequency and context of the detected anomalies. True rare behaviors may occur in specific contexts or sequences, whereas noise is typically random.

FAQ 4: My model fails to generalize across different individuals or species. What steps can I take to improve robustness?

- Problem: A model trained on data from one group of subjects performs poorly on another.

- Solution:

- Increase Data Diversity: Train the model on a more heterogeneous dataset that includes data from multiple individuals, under various conditions, and if applicable, across different species [27].

- Domain Adaptation Techniques: Use transfer learning or domain adaptation methods to fine-tune a pre-trained model on a small amount of data from the new subject group [29].

- Egocentric Alignment: For pose estimation data, align the animal's body coordinates to an egocentric (body-centric) view. This normalizes for the animal's position and orientation in the arena, making learned features more invariant to these variables [27].

- Normalize Individual Differences: Use normalized movement features (e.g., speed, acceleration) relative to the individual's typical range rather than absolute values.

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: On-Device Rare Behavior Detection with AI Bio-Loggers

This protocol is based on the method described in [28] for autonomously recording rare animal behaviors.

- Objective: To capture video evidence of rare, spontaneous behaviors in wild animals using a power-constrained bio-logger.

- Workflow:

- Detailed Methodology:

- Unlabeled Data Collection: Gather large volumes of data from low-cost sensors (e.g., accelerometer) from the target animal species.

- Teacher Model Training (on Server): On a high-performance computer, train a complex unsupervised anomaly detection model, such as an Isolation Forest, on the collected data. This model learns the distribution of normal behavior [28].

- Knowledge Distillation: Use the trained teacher model to supervise the training of a smaller, more efficient "student" model (e.g., a lightweight neural network). This compresses the knowledge into a model suitable for deployment on a low-energy microcontroller [28].

- Model Deployment: Implement the distilled student model onto the bio-logger's microcontroller.

- Continuous Monitoring & Triggering: The bio-logger runs the student model in real-time on data from the always-on, low-power sensors. When the model detects a reading classified as an outlier, it sends a signal to activate the high-power video camera.

- Video Capture: The camera records for a predefined duration, capturing the rare behavior, and then returns to a sleep mode to conserve power.

Protocol 2: Unsupervised Behavioral Motif Discovery with VAME

This protocol uses the VAME framework [27] to segment continuous animal motion into discrete, reusable motifs and identify rare transitions or sequences.

- Objective: To identify the hierarchical structure of behavior from pose estimation data and detect rarely used behavioral motifs.

- Workflow:

- Detailed Methodology:

- Pose Estimation: Use a tool like DeepLabCut to track the coordinates of key body parts (e.g., paws, nose, tailbase) from video data, creating a time series of body positions [27].

- Egocentric Alignment: For each video frame, rotate the animal's pose so that it is aligned from tailbase to nose. This removes the confounding effect of the animal's absolute orientation in the arena and focuses the model on the kinematics of the movement itself [27].

- Time Series Sampling: Extract random samples of the aligned time series data using a sliding window (e.g., 30 frames at 60 Hz, representing 500 ms of behavior) [27].

- Train VAME Model: Train a Variational Autoencoder (VAE) with recurrent neural networks (RNNs) on the time series samples. The model learns to compress each window of behavior into a low-dimensional latent vector and then reconstruct it. This forces the latent space to capture the essential spatiotemporal dynamics of the behavior [27].

- Latent Space Embedding: Pass the entire dataset through the trained encoder to project all behavioral sequences into the low-dimensional latent space.

- Motif Segmentation: Apply a Hidden Markov Model (HMM) to the continuous latent space representation. The HMM infers discrete, hidden states, which correspond to recurring behavioral motifs [27].

- Analysis: Analyze the sequence and frequency of motifs. Rare behaviors will correspond to motifs with very low usage statistics or rare transitions between motifs. Community detection algorithms can group motifs into higher-order behavioral communities [27].

Data Presentation: Quantitative Performance

Table 1: Comparison of Unsupervised Anomaly Detection Algorithms

| Algorithm | Type | Key Principle | Pros | Cons | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isolation Forest [28] [26] | Unsupervised | Isolates anomalies by randomly splitting feature space; anomalies are easier to isolate. | - Effective for high-dimensional data.- Low memory requirement. | - May struggle with very clustered normal data.- Can have higher false positives. | Initial anomaly screening, on-device applications. |

| K-Means Clustering [25] [26] | Unsupervised | Groups data into k clusters; points far from any centroid are anomalies. | - Simple to implement and interpret.- Fast for large datasets. | - Requires specifying k.- Sensitive to outliers and initial centroids. | Finding global outliers in datasets with clear cluster structure. |

| Local Outlier Factor (LOF) [30] [26] | Unsupervised | Measures the local density deviation of a point relative to its neighbors. | - Excellent at detecting local anomalies where density varies. | - Computationally expensive for large datasets.- Sensitive to parameter choice. | Detecting anomalies in data with varying densities. |

| Autoencoders [25] [30] | Unsupervised Neural Network | Learns to compress and reconstruct input data; poor reconstruction indicates anomaly. | - Can learn complex, non-linear patterns.- No need for labeled data. | - Can be computationally intensive to train.- Risk of overfitting to normal data. | Complex sensor data (e.g., video, high-frequency acceleration). |

| One-Class SVM [25] [26] | Unsupervised | Learns a tight boundary around normal data points. | - Good for robust outlier detection when the normal class is well-defined. | - Does not perform well with high-dimensional data.- Sensitive to kernel and parameters. | Datasets where most data is "normal" and well-clustered. |

Table 2: Impact of AI Anomaly Detection in Various Domains

| Domain | Application | Impact / Quantitative Result |

|---|---|---|

| Financial Services [25] | Real-time fraud detection in transactions. | Boosted fraud detection by up to 300% and reduced false positives by over 85% (Mastercard). |

| Wildlife Bio-Logging [28] | Autonomous recording of rare animal behaviors. | Enabled identification of previously overlooked rare behaviors, extending effective observation period beyond battery-limited video recording. |

| Manufacturing / Predictive Maintenance [25] | Detecting early signs of equipment failure. | Reduced maintenance costs by 10-20% and downtime by 30-40%. |

| Healthcare (Medical Imaging) [25] | Identifying irregularities in patient data. | AI detected lung cancer from CT scans months before radiologists (Nature Medicine study). |

| Software Systems [29] | Anomaly detection in system logs (ADALog framework). | Operates directly on raw, unparsed logs without labeled data, enabling detection in complex, evolving environments. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Resources for AI-Enabled Rare Behavior Detection Experiments

| Item | Function / Application in Research |

|---|---|

| Markerless Pose Estimation Software (e.g., DeepLabCut, SLEAP) [27] | Tracks animal body parts from video footage without physical markers, generating time-series data for kinematic analysis. |

| Bio-loggers with Programmable MCUs [28] | Animal-borne devices equipped with sensors (accelerometer, gyroscope, video) and a microcontroller for on-board data processing and conditional triggering. |

| Isolation Forest Algorithm [28] [26] | An unsupervised tree-based algorithm highly effective for initial anomaly detection due to its efficiency and ability to handle high-dimensional data. |

| VAME (Variational Animal Motion Embedding) Framework [27] | An unsupervised probabilistic deep learning framework for discovering behavioral motifs and their hierarchical structure from pose estimation data. |

| Adaptive Thresholding Mechanism [29] | A percentile-based method for setting anomaly detection thresholds on normal data, replacing rigid heuristics and improving generalizability across datasets. |

| Knowledge Distillation Pipeline [28] | A technique to transfer knowledge from a large, complex "teacher" model to a small, efficient "student" model for deployment on resource-constrained hardware. |

This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs for researchers and scientists working on bio-logging data verification and validation. The content is framed within the broader context of thesis research on bio-logging data verification and validation methods.

Troubleshooting Guides

Synchronization Issues Between Video and Sensor Streams

Problem: The timestamps between your video recordings and sensor data logs (e.g., from accelerometers) are misaligned, making it impossible to correlate specific animal behaviors with precise sensor readings.

Solution: A systematic approach to diagnose and resolve sync drift.

| Step | Action | Expected Outcome | Tools/Checks |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Initial Setup Check | All hardware is correctly connected for synchronization. | Verify sync cables are firmly seated at both ends [31]. |

| 2 | Signal Verification | Confirm a valid sync signal is present. | Use an oscilloscope to check sync signals between master and subordinate devices [32]. |

| 3 | Software Configuration | Session is configured to use a single, shared capture session. | In software (e.g., libargus), ensure all sensors are attached to the same session [32]. |

| 4 | Timestamp Validation | Sensor timestamps match across all data streams for the same moment. | Compare getSensorTimestamp() metadata from each sensor; they should be equal for synchronized frames [32]. |

| 5 | Session Restart | Resolves intermittent synchronization glitches. | Execute a session restart (stopRepeat → waitForIdle → repeat) after initial setup [32]. |

Validating On-Blogger Activity Detection Algorithms

Problem: How to ensure that an on-board algorithm, which summarizes or triggers data recording based on specific movements, is accurately detecting the target animal behaviors.

Solution: A simulation-based validation procedure using recorded raw data and annotated video [1].

Diagram: Simulation-based validation workflow for algorithm tuning [1].

Experimental Protocol:

- Data Collection Phase: Deploy a "validation logger" that continuously records high-rate, raw sensor data alongside synchronized video of the animal in a controlled environment [1].

- Annotation & Synchronization: Manually review the video and annotate the precise start and end times of specific behaviors of interest. Synchronize these annotations with the raw sensor data timeline [1].

- Software Simulation: Use a software tool (e.g., QValiData) to simulate the bio-logger's behavior. Feed the recorded raw sensor data into various configurations of your activity detection algorithm (e.g., adjusting thresholds, windows, or classifiers) [1].

- Performance Evaluation: For each simulation, compare the algorithm's output (e.g., "activity detected") against the ground-truth video annotations. Calculate performance metrics like precision and recall to quantify effectiveness [1].

- Iterative Refinement: Adjust the algorithm's parameters based on the performance results and re-run the simulations until the desired accuracy is achieved. The final, validated configuration is then deployed to the physical bio-loggers for field studies [1].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is validation so critical for bio-logging research? Validation is fundamental to research integrity. It ensures your data accurately reflects the animal's behavior, which is crucial for drawing correct scientific conclusions [33] [34]. In regulated life sciences, it is often mandated by bodies like the FDA to guarantee product safety and efficacy [35]. Proper validation prevents the formation of incorrect hypotheses based on erroneous data and enhances the reproducibility of your findings [33].

Q2: What are the fundamental types of data collection strategies used in resource-constrained bio-loggers? The two primary strategies are Sampling and Summarization [1].

- Sampling: Recording data in short bursts. This can be at fixed intervals (synchronous) or triggered by detected activity (asynchronous) to save power [1].

- Summarization: Continuously analyzing data on-board the logger but only storing extracted observations, such as activity counts or classified behaviors, rather than the raw data stream [1].

Q3: Our camera system uses external hardware sync, but one sensor randomly shows a one-frame delay. What could be wrong? This is a known issue in some systems. The solution is often to restart the capture session after the initial configuration.

- Action: Programmatically execute a session restart sequence (

stopRepeat,waitForIdle,repeat) after the first frame is read or after initializing the sensors. This re-initializes the data stream and often resolves the timing mismatch [32].

Q4: What does a "" warning icon in my synchronization software typically indicate? A warning icon usually signifies a configuration or connection problem. Hovering over the icon may provide a specific tooltip. Common causes include [31]:

- Sync cables that are disconnected or improperly configured.

- Outdated sensor firmware.

- A slow USB connection that cannot keep up with the data stream.

The Scientist's Toolkit

| Category | Item | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Core Hardware | Validation Data Logger | A custom logger that sacrifices battery life for continuous, high-rate raw data recording, used exclusively for validation experiments [1]. |

| Synchronization Hub (e.g., Sync Hub Pro) | A hardware device to distribute a master synchronization signal to multiple subordinate sensors, ensuring simultaneous data capture [31]. | |

| Software & Analysis | Simulation & Analysis Tool (e.g., QValiData) | Software designed to synchronize video and sensor data, assist with video annotation, and simulate bio-logger performance using recorded data [1]. |

| Data Validation Tools (e.g., in Excel or custom scripts) | Used to check datasets for duplicates, errors, and outliers, and to perform statistical validation [34] [36]. | |

| Reference Materials | Validation Protocols (IQ/OQ/PQ) | Documentation framework for Installation Qualification (IQ), Operational Qualification (OQ), and Performance Qualification (PQ) to meet regulatory standards [35]. |

| Annotated Video Library | A collection of synchronized video recordings that serve as the "ground truth" for validating sensor data against observable behaviors [1]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Hardware and Data Collection Issues

Table 1: Common Accelerometer Logger Issues and Solutions

| Symptom/Problem | Probable Cause | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Unusual bias voltage readings (0 VDC or equal to supply voltage) | Cable faults, sensor damage, poor connections, or power failure [37]. | Measure Bias Output Voltage (BOV) with a voltmeter. A BOV of 0 V suggests a short; BOV equal to supply voltage indicates an open circuit. Check cable connections and continuity [37]. |

| Erratic bias voltage and time waveform | Thermal transients, poor connections, ground loops, or signal overload [37]. | Inspect for corroded or loose connections. Ensure the cable shield is grounded at one end only. Check for signals that may be overloading the sensor's range [37]. |

| "Ski-slope" spectrum in FFT analysis | Sensor overload or distortion, causing intermodulation distortion and low-frequency noise [37]. | Verify the sensor is not being saturated by high-amplitude signals. Consider using a lower sensitivity sensor if overload is confirmed [37]. |

| Logger misses behavior events | Insufficient sensitivity in activity detection thresholds or inappropriate sampling strategy [1]. | Use simulation software (e.g., QValiData) with recorded raw data and synchronized video to validate and adjust detection parameters [1]. |

| Short logger battery life | Resource-intensive sensors (e.g., video) being overused [38]. | Implement AI-on-Animals (AIoA) methods: use low-cost sensors (accelerometers) to detect behaviors of interest and trigger high-cost sensors only as needed [38]. |

Table 2: Impact of Tag Attachment on Study Subjects

| Impact Type | Findings | Recommended Mitigation |

|---|---|---|

| Body Weight Change | A study on Eurasian beavers found tagged individuals, on average, lost 0.1% of body weight daily, while untagged controls gained weight [39]. | Use the lightest possible tag. Limit tag weight to 3-5% of the animal's body mass for birds [1] [39]. |

| Behavioral Alteration | A study on European Nightjars demonstrated that tags weighing about 4.8% of body mass were viable, but validation is crucial as impacts can vary [40]. | Conduct species-specific impact assessments. Compare behavior and body condition of tagged and untagged (control) individuals whenever possible [39]. |

Data Validation and Analysis Issues

Table 3: Data Validation and Analysis Problems

| Symptom/Problem | Probable Cause | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Inability to classify target behaviors (e.g., song) from accelerometer data. | Lack of a validated model to translate sensor data into specific behaviors [40]. | Develop a classification model (e.g., a Hidden Markov Model) using labeled data. Validate it with an independent data source, like synchronized audio recordings [40]. |

| Low precision in capturing rare behaviors | Naive sampling methods (e.g., periodic recording) waste resources on non-target activities [38]. | Employ on-board machine learning to detect and record specific behaviors. This can increase precision significantly compared to periodic sampling [38]. |

| Data appears meaningless or lacks context | Sensor data is not linked to ground-truthed observations of animal behavior [1]. | Perform validation experiments: collect continuous, raw sensor data synchronized with video recordings of the animal to build a library of behavior-signature relationships [1]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

General Bio-logging Questions