Ecological Research Methods in 2025: A Career Guide for Biomedical and Life Science Professionals

This article provides a comprehensive guide to careers in ecological research methods, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Ecological Research Methods in 2025: A Career Guide for Biomedical and Life Science Professionals

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to careers in ecological research methods, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the growing demand for ecological expertise in addressing complex challenges like biodiversity loss and climate change, which intersect with human health. The scope covers foundational career paths, from field technician to professor; detailed methodological skills like GIS, data analysis, and ecological modeling; strategies for navigating a competitive job market and skill gaps; and finally, the validation of ecological skills through interdisciplinary applications in biomedicine, including toxicology, biomarker discovery, and environmental impact assessment for clinical research.

Exploring High-Demand Careers in Ecological Research

The field of ecological research is experiencing significant expansion driven by converging global trends. Increasing recognition of climate change impacts, new regulatory frameworks, and technological advancements are creating unprecedented demand for skilled ecological researchers. This growth is not merely quantitative but represents a fundamental shift in how societies value and invest in understanding natural systems. Ecological research careers are expanding rapidly as we confront complex environmental challenges that require scientific expertise to monitor, understand, and mitigate.

This transformation is particularly evident in the policy arena. The European Union's Nature Restoration Law, which came into effect in 2024, mandates that EU member states restore at least 20% of terrestrial and marine areas by 2030 and all degraded ecosystems by 2050 [1]. This regulatory driver alone creates substantial demand for ecological research expertise to inform implementation. Similarly, the global movement toward a "Nature Positive" economy is broadening corporate environmental focus beyond carbon emissions to include biodiversity, water, and soil health [1], creating new research domains and career pathways.

Quantitative Analysis of Ecological Career Expansion

Employment Projections and Market Trends

Table 1: Ecological Career Growth Metrics and Specializations

| Metric Category | Specific Statistics | Context and Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Job Outlook | 5% projected growth (as fast as average) [2] | Approximately 3,800 new jobs to be added in next 10 years [2] |

| Current Employment | 80,000 environmental scientists and specialists employed in U.S. (2021 data) [2] | Broader category includes various ecological research positions |

| Compensation Trends | Median salary: $76,530 (2021) [2] | Top 10% averaged $129,070; highest salaries in DC, NJ, MA, CA [2] |

| High-Demand Specializations | Conservation ecologists, Environmental consultants, Climate change ecologists [3] | GIS/Remote Sensing, Rewilding, and Ecotoxicology specialists increasingly sought [3] |

Sector-Specific Growth Drivers

Table 2: Key Sectors Driving Ecological Research Demand

| Sector | Primary Growth Drivers | Representative Research Needs |

|---|---|---|

| Renewable Energy | AI energy demand; Microsoft's 20-year nuclear purchase; Google/Amazon modular reactors [4] | Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs); wildlife impact studies [5] |

| Corporate Sustainability | ESG assets under management reached $45 trillion globally in 2022 [4] | Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG) assessments; circular economy research [3] |

| Climate Adaptation | 2024 officially hottest year on record (exceeded +1.5°C above pre-industrial) [1] | Vulnerability assessments; climate resilience modeling [6] |

| Conservation Biotechnology | UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration; Biodiversity credits emergence [1] | DNA barcoding; genetic restoration techniques; automated wildlife monitoring [6] |

Key Methodologies in Modern Ecological Research

Established Protocols and Experimental Approaches

Ecological research relies on standardized methodologies that enable comparable data collection across studies and ecosystems. The Kellogg Biological Station Long-Term Ecological Research (KBS LTER) program exemplifies this systematic approach, maintaining detailed protocols for numerous ecological measurements [7]. These established methods form the foundation of evidence-based environmental decision-making.

Critical Established Protocols Include:

- Greenhouse Gas Flux Measurements: Utilizing both recirculating chamber and static chamber methods to quantify carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide fluxes between ecosystems and atmosphere [7]

- Soil Nutrient Availability Assessment: Employing ion exchange resin strips and buried bag techniques to measure nitrogen mineralization potential [7]

- Primary Production Quantification: Standardized methods for measuring aboveground and belowground net primary production across different ecosystem types [7]

- Biodiversity Monitoring: Line-point intercept methods for canopy species composition and structured butterfly surveys for pollinator monitoring [7]

Technology-Enhanced Research Methods

Modern ecological research increasingly integrates advanced technologies that expand the scale and precision of data collection. These innovations represent the evolving methodology of the field.

Remote Sensing and GIS: Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and remote sensing technologies enable ecological pattern analysis and habitat mapping at landscape scales. Specialists in this domain use spatial data to support land-use planning and conservation strategy development, with proficiency in ArcGIS, QGIS, and programming languages like Python or R for geospatial modeling becoming increasingly essential [3].

Environmental DNA (eDNA) and Molecular Techniques: DNA barcoding and other molecular methods are revolutionizing species monitoring and biodiversity assessment. These approaches allow researchers to detect species presence without direct observation, significantly enhancing monitoring efficiency and accuracy [6].

Automated Monitoring Systems: Sensor networks, drone technology, and camera traps enable continuous ecosystem monitoring with minimal disturbance. These systems generate large datasets that require sophisticated analytical approaches, creating intersections between ecology and data science [6].

Essential Research Tools and Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions in Ecological Research

| Reagent/Kit | Primary Application | Research Context |

|---|---|---|

| Permanganate Oxidizable Carbon Reagents | Soil carbon pool assessment [7] | Key indicator of soil health in agricultural and restoration ecology |

| Denitrification Enzyme Assay Components | Microbial process measurement in nitrogen cycling [7] | Critical for nutrient cycling studies in aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems |

| Lachat QuickChem 8500 Series 2 Flow Injection Analysis System reagents | Inorganic nitrogen analysis in soil and water samples [7] | Fundamental to nutrient pollution and bioavailability research |

| Elemental Combustion System standards | Total carbon and nitrogen content determination in plant/soil samples [7] | Baseline measurements for ecosystem stoichiometry studies |

| Cell Wall Analysis kits | Biofuel crop characterization [7] | Essential for renewable energy research from biomass sources |

| DNA barcoding primers and reagents | Species identification and biodiversity assessment [6] | Molecular ecology applications for conservation and monitoring |

Emerging Specializations and Methodological Innovations

High-Demand Ecological Research Specializations

The expanding ecological research landscape has generated several high-demand specializations that represent the field's evolution:

Urban Ecology: This specialization addresses the ecological dynamics within human-dominated systems. Urban ecologists design green infrastructure, conduct biodiversity surveys in cities, and advise on sustainable urban planning policies [3]. Their work integrates ecological principles with urban design to create more livable and sustainable cities.

Climate Change Ecology: Researchers in this specialization monitor and model climate change effects on ecosystems and species distributions. They develop adaptation strategies and contribute to carbon sequestration project design, working at the intersection of climate science and conservation biology [3].

Rewilding and Habitat Restoration: This growing field focuses on active ecosystem rehabilitation. Specialists design and implement rewilding projects, monitor biodiversity improvements, and engage communities in restoration efforts [3]. The methodology includes both traditional ecological knowledge and innovative restoration techniques.

Ecotoxicology: These researchers investigate pollutant impacts on ecosystems through both laboratory and field experiments. They develop strategies to mitigate chemical exposure in ecosystems and inform environmental safety regulations [3].

Methodological Workflows in Ecological Research

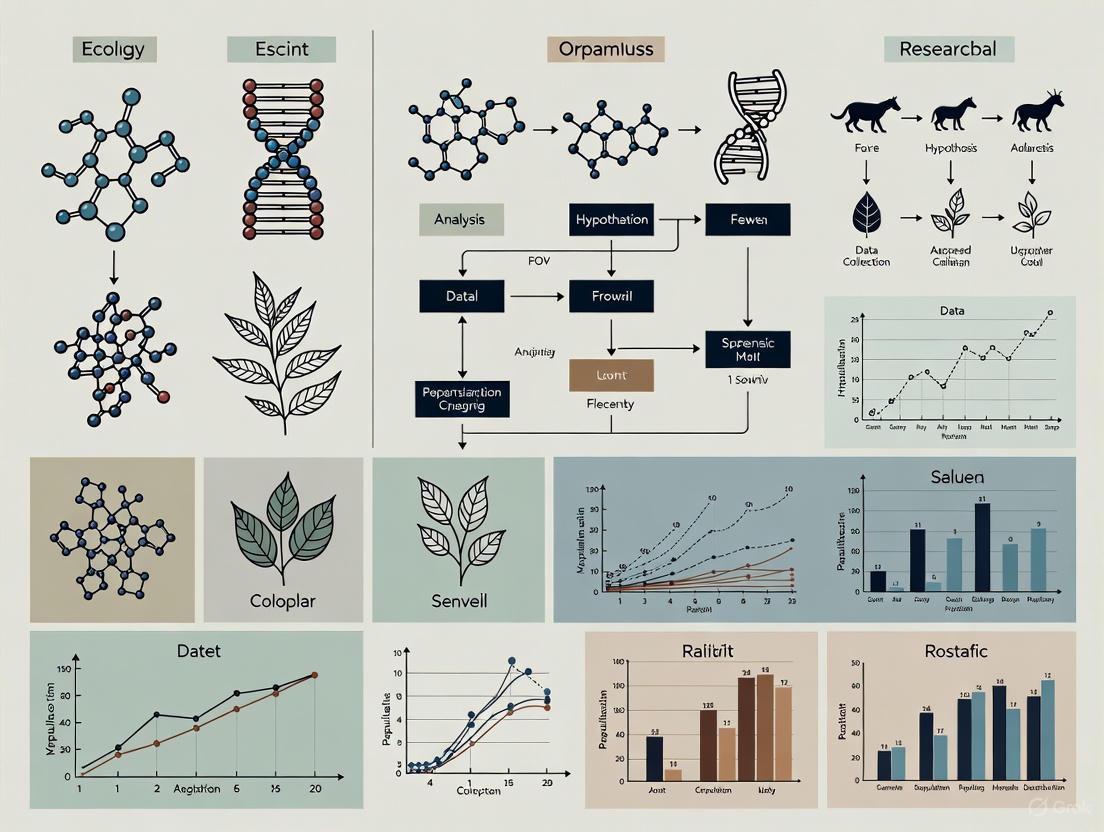

The following diagram illustrates a generalized research workflow in applied ecological research, showing the iterative process from question formulation to application:

Training and Skill Development Requirements

Modern ecological researchers typically follow structured educational pathways that combine formal education with practical experience:

Undergraduate Foundation: Bachelor's degrees in environmental science, biology, or ecology provide the essential foundation, with coursework in biology, chemistry, geology, and statistics [2]. Laboratory experience and fieldwork components are particularly valuable for developing practical skills.

Graduate Specialization: Master's and doctoral programs allow for specialization in specific ecological subdisciplines. Graduate education typically emphasizes research methodology, advanced data analysis, and scientific communication skills [2].

Practical Skill Development: Beyond formal education, ecological researchers benefit from developing competencies in GIS and spatial analysis, statistical programming (particularly R and Python), field survey techniques, and scientific communication [3].

Ecological researchers increasingly rely on standardized protocols shared through specialized repositories:

- Current Protocols Series: Comprehensive collection of over 20,000 peer-reviewed protocols across multiple subdisciplines [8]

- Springer Nature Experiments: Database combining Nature Protocols, Nature Methods, and Springer Protocols totaling over 60,000 searchable methods [8]

- Cold Spring Harbor Protocols: Interactive source of research techniques with unique features including protocol recipes and cautions [8]

- Journal of Visualized Experiments (JoVE): Peer-reviewed video journal demonstrating experimental techniques [8]

- protocols.io: Platform for creating, organizing, and sharing research protocols with interactive features [8]

The expansion of ecological research careers reflects broader societal recognition that environmental challenges require rigorous scientific solutions. The field's growth is multidimensional—encompassing new methodological capabilities, emerging specializations, and increasing integration of technological innovations. This trajectory suggests continued diversification of ecological research careers as environmental concerns become more embedded in corporate strategy, public policy, and conservation practice.

The methodological sophistication of ecological research will continue to advance, with increasing emphasis on interdisciplinary approaches that integrate molecular biology, data science, and engineering principles. This evolution will create new career opportunities while reinforcing the fundamental importance of ecological knowledge in addressing global sustainability challenges.

Conservation ecology is a mission-driven scientific discipline dedicated to understanding and mitigating the impact of human activities on Earth's biological systems. Conservation Ecologists operate at the nexus of ecological theory and applied environmental practice, working to assist the recovery of ecosystems that have been degraded, damaged, or destroyed [9]. Their work is critical in an era of rapid environmental change; scientists note that species are currently disappearing at a rate 1,000 to 10,000 times faster than the normal background rate of extinction [9]. The profession requires a synthesis of rigorous scientific research, strategic planning, and active intervention to preserve biodiversity and restore ecological functions for the benefit of both wildlife and human communities.

The role of a Conservation Ecologist extends beyond basic research. These professionals diagnose ecosystem health, design and implement restoration strategies, and monitor long-term recovery. Their work is guided by international frameworks such as the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework and is increasingly supported by significant public funding, exemplified by NOAA's recommendation of nearly $220 million for 32 habitat restoration projects in a single funding round [10]. The ultimate goal is not merely to create attractive landscapes but to recreate the complex web of relationships between plants, animals, soil microbes, and the physical environment that allows ecosystems to function autonomously [9].

Foundational Frameworks and Monitoring Priorities

Modern conservation science relies on standardized frameworks to guide data collection and policy implementation. The Driver–Pressure–State–Impact–Response (DPSIR) framework is a critical tool for understanding socio-ecological dynamics, while Essential Biodiversity Variables (EBVs) provide a common, interoperable structure for data collection and reporting [11]. These frameworks enable Conservation Ecologists to generate comparable data across regions and timeframes, facilitating transnational cooperation and evidence-based decision-making.

For the 2025-2028 period, Biodiversa+, a major European biodiversity partnership, has identified 12 refined monitoring priorities that represent urgent gaps where enhanced capacity and transnational cooperation are most needed [11]. These priorities target specific biological components and ecosystems where Conservation Ecologists focus their research and intervention efforts.

Table 1: Biodiversity Monitoring Priorities for 2025-2028

| Priority Area | Monitoring Focus |

|---|---|

| Bats | All bat species and their habitats |

| Common Species | Widespread biodiversity using standardized multi-taxa approaches |

| Genetic Composition | Intraspecific genetic diversity, differentiation, inbreeding, and effective population sizes |

| Habitats | Terrestrial, freshwater, and marine habitats and ecosystems |

| Insects | Insect biodiversity, including pollinators |

| Invasive Alien Species (IAS) | Detecting and monitoring IAS across realms, including Non-Indigenous Species in marine environments |

| Marine Biodiversity | Coastal and offshore waters, from plankton to marine megafauna and seabirds |

| Protected Areas | Biodiversity within protected areas, including Natura 2000 sites |

| Soil Biodiversity | Micro-organisms and soil fauna, from bacteria to earthworms and fungi |

| Urban Biodiversity | Biodiversity in urban, peri-urban, and urban-fluvial environments |

| Wetlands | Wetland biodiversity, including mires and peatlands |

| Wildlife Diseases | Biodiversity-related health issues affecting wild animals, livestock, and humans |

These priorities were selected based on their contribution to decision-making aligned with EU Directives and the Global Biodiversity Framework, their ability to address critical monitoring gaps, their transnational perspective, and their linkage to existing initiatives [11]. Conservation Ecologists specializing in these areas develop specific methodologies for data collection, analysis, and reporting that feed into both local management decisions and global biodiversity assessments.

Ecological Restoration: Principles and Methodologies

Core Principles of Restoration Ecology

Ecological restoration is defined by the Society for Ecological Restoration as "the process of assisting the recovery of an ecosystem that has been degraded, damaged, or destroyed" [9]. This process is distinguished from related approaches like conservation and rehabilitation by its forward-looking approach while honoring historic conditions. Conservation works to prevent future harm to intact ecosystems, while rehabilitation may improve some ecosystem functions without aiming for full recovery. In contrast, ecological restoration actively repairs damage to return an ecosystem to its historic trajectory, addressing root causes of degradation and setting the stage for natural recovery [9].

Several core ecological principles inform restoration work:

- Disturbance Regimes: Understanding natural patterns of disturbance like fires and floods that many ecosystems depend upon for regeneration.

- Ecological Succession: Facilitating the natural process where pioneer species prepare the environment for later successional species.

- Fragmentation: Addressing the division of habitats into isolated patches that impede species movement and genetic exchange.

- Community Assembly: Understanding which plants and animals naturally coexist and how they arrive at a site.

- Population Genetics: Using locally-sourced genetic material that carries adaptations to specific local conditions [9].

The economic rationale for restoration is compelling. Research indicates that restoring 350 million hectares of degraded land and water systems between now and 2030 could generate an estimated US$9 trillion in ecosystem services while removing 13 to 26 gigatons of greenhouse gases from the atmosphere [9].

Restoration Methodologies Across Ecosystems

Conservation Ecologists employ diverse methodologies tailored to specific ecosystem types and degradation causes. These approaches range from passive restoration (removing sources of disturbance) to active intervention (physical manipulation of the environment and species reintroduction).

Table 2: Common Ecological Restoration Methods and Applications

| Restoration Method | Definition | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Reforestation/Afforestation | Replanting previously forested areas or establishing trees where none existed | Riparian zones, degraded forests, carbon sequestration projects |

| Invasive Species Removal | Physical, chemical, or biological control of non-native species | Terrestrial and aquatic habitats where invasives dominate |

| Hydrological Restoration | Reestablishing natural water flows and connectivity | Wetlands, rivers, floodplains altered by drainage or diversion |

| Native Species Reintroduction | Returning extirpated species to their historic range | Apex predators, keystone species, locally extinct plants |

| Habitat Reconstruction | Recreating physical habitat structures and complexity | Coral reefs, forest canopy structure, stream morphology |

Forest and Woodland Restoration Reforestation and afforestation success depends on thoughtful species selection and site preparation. Conservation Ecologists carefully select native species mixes matched to local conditions and increasingly consider climate resilience by selecting species and genotypes that can thrive in future warmer conditions [9]. An example includes the National Forest Foundation's work restoring salmon habitat in Resurrection Creek, Alaska, where legacy gold mining had altered stream morphology [10].

Freshwater and Wetland Restoration River and wetland projects often focus on reconnecting waterways to their floodplains, removing barriers to fish passage, and restoring natural hydrology. The Hood Canal Salmon Enhancement Group's project in Washington State reconnected the Big Quilcene River to its entire 140-acre floodplain, eliminating flood hazards while creating habitat for threatened Puget Sound Chinook salmon [10]. These projects demonstrate the dual benefits of restoration for both biodiversity and community resilience.

Marine and Coastal Restoration Coastal restoration includes techniques like outplanting corals to rebuild reefs, restoring salt marshes that protect coasts from erosion and sea level rise, and rebuilding kelp forests. The Greater Farallones Association is restoring nearly 47 acres of kelp forest by planting bull kelp and removing purple sea urchins to restore balance to the ecosystem [10]. The Nature Conservancy's Pacific Coast Ocean Restoration Initiative similarly aims to catalyze large-scale restoration of rocky reef and kelp forest habitats in California [10].

The Conservation Ecologist's Toolkit: Technologies and Analytical Methods

Advanced Monitoring Technologies

Conservation technology has evolved dramatically, enabling ecologists to collect data at unprecedented scales and resolutions. These innovations are transforming how ecosystems are monitored and understood.

Table 3: Conservation Technology Innovations in 2025

| Technology | Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Artificial Intelligence (AI) | Real-time forest monitoring, species identification from images | Terra-i uses neural networks to detect deforestation at pixel level |

| Drones | Aerial surveys of remote areas, habitat mapping, anti-poaching | Coverdrone for assessing coral reef health and climate impacts |

| Advanced Camera Traps | Wildlife population monitoring, behavior studies | Modern traps with higher resolution, longer battery life, advanced sensors |

| Bioacoustics Monitoring | Biodiversity assessment in remote areas | Acoustic sensors that identify species by their vocalizations |

| Lidar | Forest structure mapping, biomass measurement | Laser-based 3D mapping of forest canopy structure |

| Environmental DNA (eDNA) | Species detection from water or soil samples | Monitoring elusive species without direct observation |

| Citizen Science Platforms | Large-scale data collection, public engagement | iNaturalist, Zooniverse for volunteer data collection |

AI-powered tools like Terra-i use real-time rainfall data and satellite imagery to predict and detect changes in forest greenness across Latin America, with neural networks that learn from processed data to improve accuracy over time [12]. Bioacoustics monitoring has emerged as a vital tool for biodiversity assessment in remote regions, capturing and analyzing ecosystem soundscapes to infer species health and diversity [12]. Environmental DNA (eDNA) techniques allow conservationists to detect species presence in water samples without visual contact, particularly useful for monitoring elusive or endangered species [12].

Data Analysis and Visualization Methods

Conservation Ecologists must transform raw data into interpretable information to guide decision-making. Quantitative analysis often involves comparing data between different groups or time periods to detect significant changes or differences.

Comparative Data Analysis When comparing quantitative variables across different groups (e.g., species populations in different habitats), Conservation Ecologists use specific graphical and statistical approaches. Appropriate visualization methods include:

- Back-to-back stemplots: Best for small datasets with two groups, preserving original data values.

- 2-D dot charts: Effective for small to moderate amounts of data, showing individual observations.

- Boxplots: Ideal for most situations, displaying five-number summaries (minimum, first quartile, median, third quartile, maximum) for easy distribution comparison [13].

Numerical summaries typically include means or medians for each group plus the difference between these central tendency measures. For example, a study comparing chest-beating rates between younger and older gorillas reported means of 2.22 and 0.91 beats per 10 hours respectively, with a difference of 1.31 beats per 10 hours [13].

Experimental Design and Workflow Conservation ecology research typically follows a systematic workflow from question formulation through to application and monitoring. The diagram below illustrates this iterative process:

Conservation Ecology Research Workflow

Career Pathways and Professional Development

Educational Requirements and Specializations

Embarking on a career as a Conservation Ecologist typically begins with specialized education. Employment in environmental fields is growing, with the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics projecting 8% growth for environmental scientists and specialists between 2020-2030, adding approximately 7,300 positions [14].

Table 4: Conservation Ecology Career Pathways and Outlook

| Position | Median Salary | Education Required | Projected Demand |

|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental Science Technician | $41,437 | Associate Degree | 11% growth (Much faster than average) |

| Soil and Water Conservationist | $45,440 | Bachelor's Degree | 7% growth |

| Wildlife Biologist | $51,620 | Bachelor's Degree | 5% growth |

| Environmental Engineer | $81,213 | Bachelor's Degree (ABET-accredited) | 4% growth |

| Climate Change Analyst | $73,217 | Bachelor's Degree (often Master's preferred) | 8% growth |

An associate degree can lead to entry-level technician positions, such as Forest and Conservation Technician or Environmental Science and Protection Technician [14]. These roles involve field data collection, research assistance, and technical support under professional supervision. Bachelor's degrees open opportunities as Soil and Water Conservationists, Wildlife Biologists, and Environmental Engineers, with the latter requiring ABET-accredited programs and often professional licensure [14].

Essential Skills and Competencies

Success in conservation ecology requires both specialized technical skills and broad transferable competencies:

Essential Technical Skills:

- Environmental Awareness: Deep understanding of ecological issues and principles.

- Inductive and Deductive Reasoning: Applying scientific approaches to formulate queries and design methodologies.

- Systems and Risk Analysis: Evaluating complex ecological systems and potential hazards.

- Data Science: Collecting, interpreting, and visualizing ecological data [14].

General Professional Skills:

- Project Management: Planning, executing, and monitoring conservation initiatives.

- Technical and Academic Writing: Communicating findings to scientific and public audiences.

- Critical Thinking: Analyzing problems in their geopolitical and social contexts [14].

Professional Development and Experiential Learning

Hands-on experience through internships, volunteer work, and apprenticeships is critical for career development. Numerous programs provide practical research opportunities:

- Research Experience for Undergraduates (REU) Programs: The National Science Foundation funds REU sites focused on ecology and evolution at institutions nationwide, including opportunities at the American Museum of Natural History, Chicago Botanic Garden, and Hubbard Brook Ecosystem Study [15].

- Federal Programs: The ESA-USGS Cooperative Summer Internship Program places students in government research positions [15].

- Conservation Corps: Organizations like the Coral Restoration Foundation offer internships in specific techniques like coral conservation and reef restoration [15].

Building professional networks through conferences (such as those organized by the Ecological Society of America) and obtaining certifications (like Environmental Professional Certification or GIS credentials) can significantly enhance career prospects [14]. Conservation Ecologists must commit to lifelong learning as technologies and ecological challenges continue to evolve.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Monitoring Protocols

Conservation Ecologists follow standardized protocols to ensure data consistency and reproducibility. Graphic protocols, which visualize methodological steps, are increasingly valued for reducing errors and streamlining knowledge transfer [16]. These visual guides help standardize techniques across research teams and facilitate the training of new personnel.

For biodiversity monitoring aligned with the Essential Biodiversity Variables framework, Conservation Ecologists implement rigorous field protocols tailored to specific taxa. For instance, bat monitoring involves acoustic detection systems and harp traps, while insect monitoring may use standardized malaise traps or transect surveys [11]. Marine biodiversity monitoring employs techniques from plankton nets to remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) for deep-sea observation.

Restoration Implementation Protocol

The diagram below illustrates a generalized protocol for implementing ecological restoration projects, from site assessment through to monitoring:

Ecological Restoration Implementation Protocol

Key Experimental Components:

- Site Assessment: Comprehensive baseline data collection including soil analysis, hydrology, biodiversity inventories, and historic condition research.

- Reference Ecosystem Selection: Identifying appropriate local ecosystems that serve as recovery targets.

- Intervention Implementation: Executing specific restoration techniques such as native planting, erosion control, or habitat structure installation.

- Monitoring Program: Establishing long-term tracking of success indicators using SMART goals (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, Time-bound) [9].

Essential Research Materials and Equipment

Conservation Ecologists utilize specialized equipment and materials for both field research and restoration implementation:

Table 5: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Equipment

| Item Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Field Monitoring Equipment | Camera traps, acoustic recorders, water quality test kits, GPS units | Data collection on species presence, behavior, and environmental conditions |

| Restoration Implementation Tools | Native plant materials, erosion control fabrics, log jams for river restoration | Active intervention to improve habitat structure and function |

| Laboratory Analysis Tools | Environmental DNA extraction kits, microscopes, genetic analyzers | Sample processing and detailed analysis of ecological materials |

| Data Collection Supplies | Soil corers, plankton nets, herbarium presses, water sampling bottles | Standardized collection of physical and biological samples |

| Technology Platforms | GIS software, statistical analysis packages, drone mapping systems | Data management, analysis, and visualization |

Successful Conservation Ecologists maintain proficiency with both traditional field techniques and emerging technologies, recognizing that appropriate tool selection is fundamental to both research quality and restoration outcomes.

The role of an environmental consultant is pivotal in bridging the gap between scientific ecological research and its practical application in regulatory compliance and sustainable development. These professionals employ rigorous research methods to assess environmental impact, guide policy, and ensure that development projects align with both ecological preservation goals and regulatory requirements. For researchers and scientists, understanding this field reveals a critical career path where scientific inquiry directly shapes environmental policy and corporate practice. The demand for these professionals is strong and growing; employment of environmental scientists and specialists is projected to grow by 8% between 2020 and 2030 [14]. This growth is fueled by increasing regulatory pressures and a global emphasis on Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) criteria, where consultants help companies navigate complex new disclosure requirements and manage climate-related risks [17] [18].

Core Responsibilities and Methodological Approaches

Environmental consultants apply a diverse toolkit of research methodologies to solve complex problems at the intersection of ecology, industry, and regulation. Their work ensures that development is scientifically sound, compliant with law, and sustainable in the long term.

Key Research Methodologies

The methodological approaches used by consultants are foundational to generating reliable data for impact assessments and are categorized as follows:

Qualitative Approaches: These methods are crucial for understanding social perceptions and experiences related to environmental impacts. Consultants use them to contextualize quantitative data within social and cultural frameworks.

- Case Studies: In-depth exploration of a specific community, project, or environmental context over time, using multiple data sources to understand complex phenomena [19].

- Interviews: Structured interactions with stakeholders, community members, and experts to gather nuanced insights, stories, and personal experiences regarding environmental changes [19].

Quantitative Approaches: These methods provide the empirical and statistical backbone for objective impact assessment.

- Surveys and Databases: Systematic data collection via tools like the American Community Survey or custom questionnaires to measure variables such as commuting patterns, resource use, or public health metrics [19].

- Statistical and Empirical Analysis: Application of statistical models to understand relationships between variables, such as the correlation between urban form, transportation systems, and greenhouse gas emissions [19].

Mixed-Method Approaches: This integrative strategy combines qualitative and quantitative methodologies to triangulate and corroborate findings, thereby increasing the validity and reliability of the overall assessment. It enriches understanding by allowing comparisons and revisions between different types of data [19].

Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA): A systematic process, often mandated by regulations like the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), to evaluate the likely environmental consequences of a proposed project or policy before proceeding. It uses a comprehensive, dynamic approach that includes public engagement, impact analysis on minority and low-income populations, and identification of mitigation strategies [19].

Cost-Benefit Analysis: A quantitative framework used to balance the investment and operational costs of projects (e.g., new public transit) against their potential environmental, social, and economic benefits, such as reduced air pollution and improved household economies for low-income commuters [19].

The Environmental Consultation Process

The following diagram visualizes the core workflow an environmental consultant follows, integrating various methodologies to deliver a compliant and sustainable outcome.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Skills and Analytical Frameworks

Success in environmental consulting requires a blend of essential scientific skills, modern analytical tools, and a firm grasp of evolving regulatory frameworks.

Foundational and Specialized Skills

The required skillset for environmental consultants is comprehensive, reflecting the interdisciplinary nature of the work.

Table: Essential Skills for Environmental Consultants

| Skill Category | Specific Skills | Application in Consulting |

|---|---|---|

| Essential Analytical Skills [14] | Environmental Awareness, Inductive & Deductive Reasoning, Systems & Risk Analysis, Data Science | Foundational understanding of ecological issues, scientific logic, interpreting complex scenarios, and data-driven decision-making. |

| Field & Technical Skills [20] | Field Ecology, GIS, Remote Sensing, Statistics, Species Identification, Habitat Restoration | Conducting on-site studies, spatial data mapping, statistical analysis of ecological data, and implementing restoration plans. |

| General Professional Skills [14] [20] | Project Management, Technical Writing, Critical Thinking, Public Speaking, Grant Writing, Regulatory Compliance | Leading projects, reporting findings, developing strategies, communicating with stakeholders, securing funding, and ensuring adherence to laws. |

Key Regulatory and Analytical Frameworks

Consultants must navigate a complex web of regulations and use standardized analytical frameworks to advise clients authoritatively.

Regulatory Compliance: Consultants are experts in regulations like the Clean Air Act and the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), which requires environmental impact statements for major federal actions [21]. They also guide clients through emerging policies like Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR), which shifts end-of-life product management costs back to producers [22].

GHG Protocol Initiative: This is a core methodological framework for quantifying a client's carbon footprint. It categorizes emissions into three scopes [19]:

- Scope 1: Direct emissions from owned or controlled sources.

- Scope 2: Indirect emissions from the generation of purchased electricity.

- Scope 3: All other indirect emissions that occur in a company's value chain, including employee commuting.

Environmental Justice Assessment: As mandated by NEPA, this is a critical evaluation to ensure that projects do not disproportionately burden minority and low-income populations. It involves meaningful community engagement and a careful analysis of impacts on vulnerable groups [19].

Quantitative Analysis in Practice: Carbon Footprint Case Study

A core function of an environmental consultant is to translate complex data into actionable insights. The following case study and data tables exemplify the quantitative rigor applied in practice.

Experimental Protocol: Commute Carbon Footprint Analysis

Objective: To quantify and analyze the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions associated with employee commutes to a central location (e.g., corporate headquarters, university campus) and model scenarios for emission reduction.

Methodology:

- Define Scope and Functional Unit: The assessment focuses on Scope 3 emissions, specifically from employee commuting. The functional unit is kg of CO₂ emitted per person for a one-way trip [19].

- Data Collection:

- Commute Distance: Gather data on the one-way distance (in miles or kilometers) from employee residences to the site. This can be collected via surveys or estimated using GIS software.

- Transportation Mode: Determine the primary mode of transport for each employee (e.g., solo car, carpool, public transit, cycling).

- Vehicle Efficiency: For personal vehicles, identify the make and model to determine fuel efficiency or use standardized emission factors.

- Emission Calculation:

- Use the following equation with standardized emission factors [19]:

Carbon Footprint (kg CO₂) = Distance (miles) × Emission Factor (g CO₂/passenger-mile) / 1000 - Model different scenarios (e.g., increased carpooling, shift to public transit) using corresponding emission factors.

- Use the following equation with standardized emission factors [19]:

- Data Analysis and Reporting: Compare the carbon footprint across different commuting modes and scenarios. Present findings to stakeholders with recommendations for sustainability initiatives (e.g., transit subsidies, preferred parking for carpools).

Data Presentation and Scenario Modeling

The following tables present the core data and results from applying the above protocol.

Table: Standard GHG Emission Factors for Transportation

| Vehicle Type | Grams of CO₂ per Passenger-Mile | Grams of CO₂ per Passenger-Kilometer |

|---|---|---|

| SUV | 416 | 258 |

| Average U.S. Car | 366 | 227 |

| Light Rail | 179 | 111 |

| Toyota Prius | 118 | 73 |

| Metro | 94 | 58 |

| Motor Bus | 221 | 137 |

Source: Demographia, 2005; EIU, 2008; O'Toole, 2008, as cited in [19].

Table: Carbon Footprint Analysis of a 29-Mile Commute (One-Way)

| Scenario | Vehicle Type | Passengers | Emission Factor (g CO₂/pass-mile) | kg CO₂ per Trip |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Driving Solo | Average U.S. Car | 1 | 366 | 10.61 |

| Sharing with One Person | Average U.S. Car | 2 | 183 | 5.31 |

| Driving Solo in Efficient Car | Toyota Prius | 1 | 118 | 3.42 |

| Driving Efficient Car & Carpooling | Toyota Prius | 4 | 29.5 | 0.86 |

| Riding a Mildly Occupied Bus | Motor Bus | 15 | 14.7 | 0.43 |

| Riding a Highly Occupied Bus | Motor Bus | 30 | 7.4 | 0.21 |

Source: Adapted from [19].

The data reveals that behavioral and technological changes, such as carpooling in a fuel-efficient vehicle, can reduce emissions by nearly 92% compared to driving solo in an average car. This provides a strong, data-driven foundation for consultants to recommend specific sustainability measures.

Career Pathways and Professional Outlook

For ecological researchers, environmental consulting offers a dynamic and financially rewarding career path with opportunities for significant impact.

Salary and Career Trajectory

Compensation in environmental consulting is competitive and reflects the high level of expertise required.

Table: Environmental Consulting Career Progression and Compensation

| Career Level | Typical Roles | Average Annual Salary |

|---|---|---|

| Entry-Level [23] | Environmental Technician, Junior Analyst | $60,000 - $75,000 |

| Mid-Career [23] | Environmental Consultant, Project Manager | $85,000 - $110,000 |

| Senior-Level / Specialist [14] [23] | Senior Consultant, ESG Manager, Sustainability Director, Environmental Risk Manager | $120,000 - $200,000+ |

The highest-paid roles are increasingly found in specialized areas like ESG consulting and climate change analysis, where deep technical knowledge intersects with corporate strategy and regulatory advisory [23].

Educational Pathways and Skill Development

A successful career typically begins with a bachelor's degree in environmental science, engineering, or a related field [14] [23]. Progression often involves:

- Advanced Degrees: A master's in environmental management or an MBA can provide a significant advantage for leadership roles [23].

- Hands-on Experience: Internships and volunteer work with conservation groups or sustainability-focused businesses are critical for building a practical skill set and professional network [14].

- Certifications and Specialized Training: Credentials such as the Environmental Professional Certification or expertise in GIS mapping are highly valued by employers to demonstrate specialized competence [14].

The role of an environmental consultant is a professionally and intellectually demanding career that sits at the critical junction of ecological science, public policy, and industrial development. It requires a robust and interdisciplinary skill set, from field ecology and quantitative data analysis to stakeholder engagement and project management. For the ecological researcher, this field offers a tangible avenue to apply rigorous scientific methodologies—from GHG emissions modeling to environmental justice assessments—to solve real-world problems. As global focus on sustainability and ESG criteria intensifies, the demand for consultants who can provide data-driven, compliant, and ethical solutions will only continue to grow, making it a promising and impactful career path for scientists dedicated to shaping a more sustainable future.

Ecotoxicology is a critical scientific discipline that investigates the harmful effects of chemical, biological, and physical agents on living organisms within their natural environments [24]. This field serves as a vital link between traditional toxicology—which focuses on human health—and ecology, which studies the interactions between organisms and their environment. Ecotoxicologists specialize in predicting, measuring, and explaining the frequency and severity of adverse effects caused by environmental toxins [24]. Their work is essential for developing evidence-based environmental protection policies and bringing a greater understanding of the hazards and risks to which organisms are exposed.

The role of ecotoxicologists has become increasingly important in addressing complex global challenges such as chemical pollution, biodiversity loss, and ecosystem degradation. These professionals employ a variety of research approaches, including field observations, laboratory experiments, and computer modeling, to unravel the complex interactions between pollutants and biological systems [25]. By studying effects at multiple biological levels—from molecular and cellular responses to population-level impacts and ecosystem-wide consequences—ecotoxicologists provide crucial insights that inform regulatory decisions, chemical safety assessments, and environmental management strategies.

Core Responsibilities and Research Focus

Primary Duties and Activities

Ecotoxicologists engage in diverse activities that span field, laboratory, and regulatory domains. Their core responsibilities include conducting ecotoxicity testing and risk assessment on new chemicals before they enter the market to ensure they won't cause adverse ecological effects [26] [24]. This involves taking samples of water, soil, sediment, animals, and plants to measure ecosystem health, determine exposure levels, and assess changes attributable to specific pollution sources [24]. Ecotoxicologists also develop models to explain the negative effects chemicals can have on ecosystems and collaborate with biochemists and other scientists in multidisciplinary teams to address complex environmental challenges [24].

A significant aspect of their work involves monitoring studies of invertebrates and fish in polluted environments to assess the impact of toxins within food chains [24]. When environmental emergencies occur, such as chemical spills, ecotoxicologists may be called upon to contribute to clean-up and recovery efforts [24].他们还负责根据生物体暴露的毒物浓度和周期评估潜在风险,并为空气、土壤、沉积物或水中的化学、生物和物理制剂的安全水平制定标准或指南,例如环境质量标准 [24].

Key Research Areas

Ecotoxicological research encompasses several critical areas of study. One major focus is bioaccumulation and biomagnification, where pollutants accumulate in organisms' tissues and become more concentrated as they move up the food chain [27]. This research is crucial for understanding how top predators, including humans, can be exposed to dangerous levels of contaminants even when environmental concentrations appear low. Another vital research area involves combined pollution effects, where ecotoxicologists study how mixtures of pollutants interact to produce ecological effects that may differ from those of individual contaminants [28].

Ecotoxicologists also investigate the molecular mechanisms of toxicity, examining how pollutants cause damage at cellular and subcellular levels. For example, recent research has demonstrated that nickel exposure alters the properties of protamine-like proteins and how they bind to DNA in marine mussels (Mytilus galloprovincialis), thereby changing sperm chromatin structure and potentially impacting reproductive success [29]. Similarly, studies on microplastics have revealed their ability to induce pro-inflammatory and cytotoxic responses in human and mouse intestinal cell lines [29].

Table 1: Key Research Areas in Ecotoxicology

| Research Area | Description | Example Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Bioaccumulation and Biomagnification | Study of pollutant accumulation in tissues and concentration through food webs | Predators at top of food chain accumulate highest pollutant levels [27] |

| Combined Pollution Effects | Investigation of interactions between multiple pollutants | Ecotoxicological effects depend on concentration combinations and ecosystem type [28] |

| Molecular Toxicity Mechanisms | Examination of cellular and subcellular damage from pollutants | Nickel alters DNA-binding properties of protamine-like proteins in marine mussels [29] |

| Reproductive Toxicology | Study of pollutant impacts on reproductive health | Mercury causes changes in gonadal morphology and sperm chromatin structure [29] |

| Ecosystem-Level Impacts | Assessment of pollution effects on ecosystem structure and function | Pollution reduces biodiversity and disrupts biogeochemical cycles [27] |

Fundamental Ecotoxicological Methods

Ecotoxicologists employ a diverse array of research methods to understand how pollutants affect biological systems across different levels of organization, from molecules to ecosystems. These approaches can be broadly categorized into observational methods, experimental approaches, and modeling techniques [25]. Each method offers distinct advantages and limitations, and integrating multiple approaches often provides the most comprehensive understanding of ecological impacts [25].

Observational and Field Methods

Observational methods involve systematic data collection on ecological phenomena without environmental manipulation [25]. These approaches provide critical information about pollution effects under real-world conditions and help identify patterns that may not be apparent in controlled laboratory settings. Field surveys capture species abundance and distribution in contaminated versus reference sites, while long-term monitoring programs track ecological trends over extended periods [25]. Remote sensing uses satellite imagery to monitor large-scale ecosystem changes, allowing ecotoxicologists to assess impacts across broad spatial scales [25].

Field sampling techniques are essential for ecotoxicological investigations. Ecotoxicologists collect water, soil, sediment, and biological samples from affected areas to measure contaminant levels and assess ecosystem health [24]. For example, in investigating a fish population decline, an ecotoxicologist might take water samples from a contaminated stream and analyze them for potential toxicants [24]. Field observations also provide context for interpreting laboratory results and help ensure that experimental studies address environmentally relevant scenarios.

Experimental Approaches

Experimental methods in ecotoxicology involve manipulating variables to test specific hypotheses about how pollutants affect biological systems [25]. Controlled laboratory experiments isolate specific factors, such as chemical concentration or exposure duration, to establish cause-effect relationships [25]. These studies might examine the effects of a toxin at various concentrations on laboratory animals, human cell cultures, or model organisms [26]. Laboratory experiments allow for precise control over environmental variables and facilitate repeated trials under standardized conditions [25].

Field manipulations represent another important experimental approach, where researchers alter conditions in natural settings to study pollutant effects [25]. These experiments offer greater ecological realism than laboratory studies while still allowing researchers to test specific hypotheses. Examples include nutrient addition experiments in aquatic ecosystems or controlled pesticide application studies in terrestrial environments [25]. Field manipulations bridge the gap between highly controlled laboratory studies and purely observational approaches, providing insights into how pollutants affect complex ecological systems.

Modeling and Comparative Methods

Theoretical models provide a framework for testing hypotheses and predicting ecological outcomes under different pollution scenarios [25]. Ecotoxicologists use statistical models to quantify relationships between pollutant exposure and biological effects, population dynamics models to project species growth and decline in contaminated environments, and ecosystem models to simulate how pollutants affect energy and nutrient flows [25]. These models enable predictions of future ecological states and facilitate exploration of different management scenarios [25].

Comparative methods analyze patterns across species, habitats, or ecosystems to infer ecological principles related to pollution effects [25]. For example, researchers might compare pollutant sensitivity across different taxonomic groups or examine how the same contaminant produces different effects in marine versus terrestrial environments [25]. These comparative approaches help identify general patterns in ecotoxicological responses and inform the development of broader ecological principles.

Experimental Protocols in Ecotoxicology

Standard Aquatic Toxicity Testing

Aquatic toxicity testing represents a fundamental protocol in ecotoxicology for assessing the impacts of pollutants on water-dwelling organisms. The standard approach involves exposing test organisms to various concentrations of a chemical stressor under controlled laboratory conditions. Test species typically include algae (Pseudokirchneriella subcapitata), water fleas (Daphnia magna), and fish (Danio rerio or Oncorhynchus mykiss) to represent different trophic levels. The experimental workflow begins with the preparation of stock solutions of the test chemical, followed by serial dilution to achieve a range of concentrations that are typically logarithmically spaced.

During the exposure phase, organisms are randomly assigned to treatment groups, including a negative control, and maintained under standardized conditions with appropriate water quality parameters (temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen, hardness). The test duration varies by species and life stage but typically ranges from 24 to 96 hours for acute tests and up to 21 days for chronic assessments. Mortality is the primary endpoint for acute toxicity, while sublethal endpoints for chronic tests include growth, reproduction, and behavioral changes. Data analysis involves calculating LC50 (lethal concentration for 50% of the population) or EC50 (effective concentration for 50% of the population) values using statistical methods such as probit analysis or nonlinear regression.

Molecular Ecotoxicology Protocol: Heavy Metal Effects on Sperm Chromatin

Recent advances in ecotoxicology have enabled detailed investigation of pollutant effects at the molecular level. The following protocol outlines methods for assessing heavy metal impacts on sperm chromatin structure, based on studies with the Mediterranean mussel (Mytilus galloprovincialis) [29]. This approach provides insights into the reproductive toxicity of environmental contaminants.

Experimental Protocol:

Sample Collection and Acclimation: Collect adult marine organisms (e.g., Mytilus galloprovincialis) from reference sites during reproductive season. Acclimate in laboratory conditions with controlled temperature, salinity, and photoperiod for 7 days prior to experimentation.

Exposure Setup: Prepare exposure concentrations of the test heavy metal (e.g., nickel chloride, mercury, or hexavalent chromium) in filtered seawater. For nickel, concentrations of 5, 15, and 35 µM have been used in previous studies [29]. Include a negative control with no added metal. Use at least three replicates per treatment with multiple organisms per replicate.

Exposure Period: Expose organisms for a defined period (e.g., 24-96 hours) with continuous aeration and renewal of exposure media every 24 hours to maintain stable chemical concentrations.

Tissue Sampling and Homogenization: After exposure, dissect gonadal tissue and homogenize in appropriate buffer (e.g., Tris-HCl buffer with protease inhibitors) using a glass-Teflon homogenizer. Centrifuge homogenate to obtain clear supernatant for analysis.

Protein Extraction and Analysis: Extract nuclear proteins (including protamine-like proteins) using acid extraction methods. Separate proteins using polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and characterize using mass spectrometry techniques [29].

DNA-Binding Assessment: Analyze DNA-binding properties of protamine-like proteins using gel retardation assays or MNase accessibility tests. Increased MNase accessibility indicates altered chromatin structure and potential reproductive toxicity [29].

Molecular Marker Analysis: Measure expression of stress response genes (e.g., PARP) using quantitative PCR or Western blotting to assess cellular stress responses to heavy metal exposure [29].

Statistical Analysis: Compare results between treatment groups and controls using appropriate statistical tests (e.g., ANOVA followed by post-hoc tests) to determine significant treatment effects.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Molecular Ecotoxicology

| Reagent/Equipment | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Heavy Metal Salts (NiCl₂, HgCl₂, K₂Cr₂O₇) | Exposure medium preparation | Creating environmentally relevant concentration ranges for toxicity testing [29] |

| Protamine-like Protein Isolation Kits | Nuclear protein extraction | Studying effects of pollutants on sperm chromatin structure [29] |

| MNase (Micrococcal Nuclease) | Chromatin accessibility assessment | Quantifying changes in sperm chromatin structure following pollutant exposure [29] |

| PARP Antibodies | Apoptosis marker detection | Measuring cellular stress responses in contaminated organisms [29] |

| qPCR Reagents | Gene expression analysis | Quantifying stress gene expression changes in response to pollutants [29] |

Signaling Pathways of Pollutant Impacts

Molecular Pathways of Heavy Metal Toxicity

Heavy metals such as nickel, mercury, and chromium exert toxic effects through specific molecular pathways that disrupt cellular function. Nickel exposure has been shown to induce oxidative stress and apoptosis in human corneal epithelial cells through a defined signaling cascade [29]. The pathway begins with nickel ions entering cells through divalent metal transporters, followed by generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) through Fenton-like reactions. Increased ROS production leads to mitochondrial membrane depolarization, triggering the release of cytochrome c and activation of caspase-9 and caspase-3, ultimately resulting in apoptotic cell death [29].

At the reproductive level, heavy metals interfere with chromatin structure through specific mechanisms. Studies with Mytilus galloprovincialis have demonstrated that nickel and chromium exposure alter the DNA-binding properties of protamine-like proteins, major basic nuclear protein components of sperm chromatin [29]. These alterations increase MNase accessibility to sperm chromatin, indicating structural instability. The metals also upregulate expression of DNA damage repair enzymes such as PARP, reflecting activation of cellular stress response pathways [29]. These molecular changes potentially compromise reproductive success by affecting sperm viability and function.

Ecosystem-Level Impact Pathways

Pollutants trigger cascading effects through ecosystems via interconnected pathways that extend beyond initial molecular interactions. Chemical contaminants can disrupt food webs through processes of bioaccumulation and biomagnification [27]. Bioaccumulation occurs when pollutants build up in organism tissues over time, while biomagnification describes the increasing concentration of contaminants at successively higher trophic levels. These processes can result in top predators accumulating dangerous levels of pollutants even when environmental concentrations are relatively low [27].

Pollutants also disrupt biogeochemical cycles essential for ecosystem function. For example, acid rain—caused by air pollution from sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides—acidifies soils and water bodies, affecting nutrient availability for plants and aquatic organisms [27]. Excessive nutrient runoff from agricultural activities can cause eutrophication in water bodies, leading to algal blooms that deplete oxygen and kill fish and other aquatic life [27]. These ecosystem-level pathways demonstrate how localized pollution can generate far-reaching ecological consequences through interconnected biological and geochemical processes.

Essential Research Tools and Databases

Ecotoxicologists utilize specialized tools and databases to support their research and risk assessments. The ECOTOX Knowledgebase, maintained by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, is a comprehensive, publicly available resource that provides information on adverse effects of single chemical stressors to ecologically relevant aquatic and terrestrial species [30]. This database contains over one million test records compiled from more than 53,000 references, covering over 13,000 species and 12,000 chemicals [30]. The Knowledgebase is updated quarterly with new data and features, offering search functionality by chemical, species, or effects, with data visualization capabilities for exploring results [30].

Laboratory equipment for ecotoxicology includes standard analytical instruments such as gas chromatographs-mass spectrometers (GC-MS) for identifying organic contaminants, atomic absorption spectrometers (AAS) and inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometers (ICP-MS) for metal analysis, and various molecular biology tools for assessing genetic and protein-level responses to pollutants. Field equipment includes water and sediment samplers, portable water quality meters, and specialized apparatus for collecting biological samples without causing undue stress to organisms or habitat disruption.

Professional Tools and Frameworks

Ecotoxicologists employ various conceptual frameworks to guide their research and interpretation of findings. The Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) framework organizes knowledge about pollutant effects by linking molecular initiating events to individual-level outcomes and population-level consequences. Risk assessment models provide structured approaches for evaluating the likelihood and severity of adverse ecological effects from chemical exposures, incorporating toxicity data, exposure estimates, and assessment factors to derive protective environmental quality standards [24].

Statistical software packages (e.g., R, Python with ecotoxicological libraries) enable sophisticated analysis of dose-response relationships, population modeling, and multivariate analysis of community-level data. Geographic Information Systems (GIS) facilitate spatial analysis of contamination patterns and their relationship to ecological endpoints. These professional tools enhance the rigor and applicability of ecotoxicological research to environmental decision-making.

Table 3: Essential Databases and Tools for Ecotoxicology Research

| Resource | Type | Application |

|---|---|---|

| ECOTOX Knowledgebase | Database | Source of toxicity data for chemical benchmarks and ecological risk assessments [30] |

| Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) Models | Modeling Tool | Predicting toxicity based on chemical structure when empirical data are limited [30] |

| Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) Framework | Conceptual Framework | Organizing knowledge linking molecular events to ecological outcomes |

| Geographic Information Systems (GIS) | Analytical Tool | Spatial analysis of contamination patterns and ecological impacts |

| Statistical Software (R, Python) | Analytical Tool | Dose-response analysis, population modeling, multivariate statistics |

Career Context in Ecological Research

Ecotoxicology represents a specialized career path within the broader field of ecological research methods and approaches [25]. Professionals in this discipline draw on a variety of scientific domains to predict, measure, and explain the frequency and severity of adverse effects of environmental toxins on living organisms [24]. The field offers diverse employment opportunities in government agencies, academic institutions, consulting firms, and industry, with growing demand for specialists who can address complex chemical pollution problems [26] [24].

Educational Pathways and Skill Requirements

Most environmental toxicologists have advanced degrees in this specialization, typically entering graduate school with bachelor's degrees in biology, chemistry, environmental chemistry, or ecology [26]. Graduate programs build on these foundations, providing additional education in molecular and developmental biology, neuroscience, and risk assessment [26]. They also teach students how environmental contaminants relate to other life and earth sciences such as microbiology, botany, entomology, soil science, hydrology, and atmospheric science [26].

Essential skills for ecotoxicologists include strong foundations in biology and chemistry, ability to interpret data clearly, knowledge of environmental legislation and regulations, and proficiency with laboratory equipment [24]. Equally important are soft skills such as attention to detail, project management, oral and written communication, and personal integrity [24]. These competencies enable ecotoxicologists to effectively conduct research, communicate findings, and contribute to environmental protection decisions.

Professional Context and Opportunities

Ecotoxicologists work in a variety of settings, dividing their time between laboratory, office, and field environments [24]. In the lab, they test samples and conduct toxicity experiments; in the office, they analyze data and prepare reports; and in the field, they collect samples and conduct environmental investigations [24]. Employment settings include federal, state/provincial, and municipal government departments; colleges, universities, and research institutes; environmental consulting firms; and industries such as mining, forestry, and chemical production [24].

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, environmental scientists and specialists, including ecotoxicologists, earned a median annual wage of $80,060 in 2024, with the highest 10% earning more than $134,830 [31]. The federal government remains the highest-paying industry for these professionals, reporting a median salary of $103,180 [26]. Job demand for environmental specialists is projected to grow, with specialists in environmental toxicology having advantages over biologists and other scientists without specialized training in toxicology [26].

Climate change ecologists operate at the critical intersection of ecological science and global environmental change. Their work involves diagnosing the impacts of a shifting climate on biological systems and formulating evidence-based strategies to both mitigate the causes and adapt to the consequences. This discipline is foundational to a thesis on careers in ecological research, as it demands a synthesis of diverse methodological approaches—from field observation to computational modeling—to address one of the most pressing challenges of our time. Ecologists study relationships between living things and their environment across various levels, from individual organisms to entire biospheres [32]. In the context of climate change, this involves understanding how climatic disruptions affect species interactions, population dynamics, community structure, and ecosystem function [32]. The core of this profession is not merely to document change but to develop proactive, sustainable, and scalable interventions.

The urgency of this field is underscored by scientific data showing the Earth is already about 1.1°C warmer than in the 1800s, with climate models projecting a rise of 2.5°C to 2.9°C this century without significant action [33]. These changes are not distant threats; they are current drivers of widespread and rapid alterations in our planet’s atmosphere, oceans, and ecosystems, making the climate change ecologist's role increasingly vital [33]. The profession is inherently interdisciplinary, requiring knowledge of biology, chemistry, botany, zoology, and mathematics to analyze complex systems [34]. Ultimately, the work of these scientists informs policy, guides conservation, and helps shape a sustainable future for both natural systems and human societies.

Core Concepts: Adaptation vs. Mitigation

A climate change ecologist must be proficient in two fundamental, complementary strategies: adaptation and mitigation. Distinguishing between these concepts is essential for developing effective interventions.

Climate Change Adaptation refers to actions that help reduce vulnerability to the current or expected impacts of climate change, such as weather extremes, sea-level rise, biodiversity loss, and food insecurity [33]. The goal is to adjust to life in a changing climate, reducing risks from harmful effects and making the most of any potential beneficial opportunities [35]. For example, this could involve planting drought-resistant crops, building flood defenses, or restoring mangroves to protect coastlines from storm surges [33].

Climate Change Mitigation, conversely, involves actions to reduce or prevent greenhouse gas emissions from human activities, or to enhance carbon sinks that remove these gases from the atmosphere [36]. The goal is to avoid significant human interference with Earth's climate and stabilize greenhouse gas levels in a timeframe that allows ecosystems to adapt naturally [35]. Key mitigation strategies include transitioning from fossil fuels to renewable energy, enhancing energy efficiency, and protecting and restoring forests which act as critical carbon sinks [36].

Even with swift and significant emission reductions, the climate impacts from emissions already in the system will continue for decades, making adaptation an essential parallel strategy to mitigation [33]. The following table summarizes the key distinctions and examples.

Table 1: Core Concepts of Adaptation and Mitigation

| Aspect | Adaptation | Mitigation |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Reduce vulnerability to climate impacts; adjust to life in a changing climate [33] [35] | Reduce or prevent greenhouse gas emissions; stabilize greenhouse gas levels [36] [35] |

| Key Actions | Adjusting agricultural practices, building defensive infrastructure, restoring protective ecosystems, enhancing early warning systems [33] | Transitioning to renewable energy, improving energy efficiency, sustainable land management, conserving and restoring forests [36] |

| Typical Scope & Scale | Often local to regional, addressing specific, localized impacts [33] [35] | Local to global, with benefits for the global climate system [36] [37] |

| Timeframe of Impact | Near- to long-term, dealing with both current and future impacts [33] | Medium- to long-term, with effects on future climate warming [35] |

| Example | Tuvalu reclaiming land and building defenses against sea-level rise [33] | Mauritius integrating battery storage to support grid-connected renewable energy, avoiding 81,000 tonnes of CO₂ annually [36] |

Quantitative Foundations and Ecological Research Methods

Robust, data-driven methodologies underpin all effective climate change ecology. The field relies on advanced quantitative tools to interpret complex observations, distinguish climate signals from noisy data, and predict future ecological states [38] [39]. The application of sophisticated mathematical and statistical models is crucial for problems like estimating population dynamics, modeling the impacts of anthropogenic change, and predicting the spread of invasive species or diseases [38].

Key Research Approaches

Ecologists employ a suite of research methods, each with strengths and applications, to build a comprehensive understanding of climate change effects.

Observation and Field Work: This involves systematic data collection in natural settings without manipulation, providing high ecological realism [25] [34]. Techniques range from direct surveys (e.g., visually counting species, using video sledges for seafloor observation) to indirect surveys (e.g., tracking animal scat or footprints) [34]. Long-term monitoring programs, such as the Hubbard Brook Ecosystem Study, are essential for tracking ecological trends over time [25]. Data collected can be qualitative (descriptive, e.g., cloud cover) or quantitative (numerical, e.g., species count, pH levels), with the latter being more reliable for statistical analysis [34].

Experimentation: This approach tests hypotheses by manipulating variables. Manipulative experiments, conducted in the lab or field, involve deliberate alteration of a factor (e.g., reducing predator numbers to study prey response) to establish causality [25] [34]. Natural experiments leverage unintended ecosystem manipulations caused by events like natural disasters or human-induced changes, offering insights at large spatial or temporal scales, though without controlled conditions [34].

Modeling: Ecological methods rely heavily on statistical and mathematical models to analyze data, predict future states, and understand systems too complex for direct study [25] [34]. Modeling includes statistical models to quantify relationships, population dynamics models to project species growth, and ecosystem models to simulate energy and nutrient flows [25]. This is particularly vital for forecasting outcomes under different climate scenarios [34].

Table 2: Ecological Research Methods and Their Applications in Climate Change

| Method | Description | Strengths | Common Tools & Techniques |

|---|---|---|---|

| Observational & Field Work [25] [34] | Systematic data collection without environmental manipulation. | Captures real-world complexity and unexpected interactions; essential for long-term trends. | Field surveys, remote sensing, satellite imagery, transects, quadrat sampling, mark-recapture methods. |

| Experimental [25] [34] | Manipulation of variables to test hypotheses about ecological processes. | Can establish causal relationships; offers control and replication. | Controlled lab experiments, field manipulations (e.g., nutrient addition), exclusion studies. |

| Modeling [25] [34] | Using mathematical or computational representations to simulate ecological processes. | Predicts future states; integrates data from various sources; explores different scenarios. | Statistical models, population dynamics models, ecosystem models, simulations. |

| Molecular & Genetic [25] | Using molecular tools to study ecological interactions. | Reveals cryptic biodiversity, evolutionary relationships, and population structure. | DNA sequencing, stable isotope analysis (for tracing energy flow). |

| Paleoecological [25] | Reconstructing past ecological conditions. | Provides long-term context and baseline data on past climate and species distributions. | Fossil analysis, sediment/ice core sampling. |

Statistical Rigor in Climate Change Ecology

Given the reliance on observational data, climate change ecologists must be adept at statistical methods that account for unique challenges. A review of marine climate change literature revealed common weaknesses that can hinder reliable inferences [39]. Key considerations for defensible analysis include:

- Accounting for Autocorrelation: Ecological data collected over time (temporal) or space (spatial) often show inherent dependencies, where consecutive data points are not independent. Ignoring this autocorrelation can inflate the significance of statistical results [39].

- Including Multiple Drivers: Climate change is rarely the sole driver of ecological change. Statistical models must consider other anthropogenic stressors like fishing, pollution, land-use change, and invasive species to avoid attributing an effect solely to climate [39].

- Reporting Rates of Change: To be useful for synthesis and comparison across studies, ecologists should report quantitative metrics on rates of change (e.g., km shifted per decade, population change per °C warming) [39].

Research Methodology Workflow

Developing Adaptation Strategies

Adaptation strategies are tailored to reduce specific climate risks. A climate change ecologist develops these strategies based on a thorough vulnerability assessment of a system, whether a natural ecosystem, a working landscape like a farm, or a human community.

Key Adaptation Frameworks and Examples

- National Adaptation Plans (NAPs): These are comprehensive medium- and long-term strategies developed by nations to prioritize adaptation efforts, integrate climate considerations into policies, and mobilize finance. For example, Bhutan, the world's first carbon-negative country, has finalized a National Adaptation Plan deeply rooted in its Gross National Happiness ethos [33].

- Nature-based Solutions: These strategies utilize ecosystems and their services to address climate impacts. For instance, Cuba and Colombia are leading the way on restoring mangroves, wetlands, and other crucial ecosystems to protect against floods and drought [33]. Similarly, protecting and restoring coastal wetlands like tidal marshes and seagrasses defends coasts against floods and sea-level rise by buffering storm surges [40].

- Technological and Infrastructural Adaptation: This includes measures like building stronger flood defenses, relocating infrastructure from vulnerable coastal areas, and enhancing water storage and use systems [33]. In the Pacific, Tuvalu has reclaimed a substantial strip of land to protect against sea-level rise and storm waves beyond 2100 [33].

- Community and Livelihood Adaptation: For farming communities, adaptation can mean planting crop varieties that are more resistant to drought, practicing regenerative agriculture, or adopting climate-smart practices that ensure food security [33]. This is crucial for enhancing the resilience of those disproportionately affected by climate change, including women, Indigenous Peoples, and local communities [33].

Developing Mitigation Strategies