Developing and Testing Ecological Indicators: A Comprehensive Guide for Environmental Researchers and Risk Assessment

This article provides a systematic framework for the development, testing, and validation of ecological indicators for researchers and environmental professionals.

Developing and Testing Ecological Indicators: A Comprehensive Guide for Environmental Researchers and Risk Assessment

Abstract

This article provides a systematic framework for the development, testing, and validation of ecological indicators for researchers and environmental professionals. Covering foundational concepts to advanced applications, it explores how indicator species reflect environmental conditions and integrate cumulative ecosystem effects. The content examines selection criteria based on conceptual soundness, feasibility, and response variability, alongside practical methodologies for processing complex assemblage data using statistical tools. It addresses common challenges in implementation and offers optimization strategies, while establishing robust validation protocols and comparative assessment frameworks. Particularly relevant for pharmaceutical and synthetic drug production impact assessment, this guide synthesizes current research trends and technological advancements to support effective ecological monitoring and risk management decisions.

The Science Behind Ecological Indicators: Foundations and Selection Criteria

Technical Troubleshooting Guides

Guide: Addressing Poor Correlation Between Indicator Values and Measured Environmental Parameters

Problem: Calculated mean ecological indicator values (EIVs) show a weak or unexpected correlation with in-situ measured environmental parameters (e.g., soil pH, temperature).

Solution: This is often related to the choice of the EIV system or the weighting method used to calculate the mean values [1].

- Step 1: Verify the EIV System Coverage. Check if the EIV system you are using contains indicator values for a high percentage of the taxa in your vegetation plots. Systems with low coverage can lead to biased results. The Ecological Indicator Values for Europe (EIVE) 1.0 system, with values for 14,835 taxa, is recommended to minimize this issue [1].

- Step 2: Re-calculate Mean EIVs Using an Unweighted Approach. Research indicates that using an unweighted (presence-based) mean often performs as well as or better than cover-weighted means. Re-run your analysis using the simple arithmetic mean of species EIVs, as this approach effectively leverages the "wisdom of the crowd" by incorporating data from more taxa [1].

- Step 3: Compare Systems if Necessary. If the correlation remains poor, compare results using a different, well-established regional EIV system (e.g., Landolt for the Alps) to see if it better captures local conditions [1].

Guide: Interpreting Weak or Inconsistent Signals from Biological Indicators in Aquatic Toxicity Testing

Problem: Results from aquatic toxicity tests using bioindicators are unclear or do not show a clear dose-response relationship with a chemical stressor.

Solution: This can arise from issues with test organism sensitivity, experimental conditions, or endpoint measurement [2].

- Step 1: Confirm Test Organism Sensitivity and Health. Ensure the test organisms (e.g., freshwater shrimp, mayfly larvae) are appropriate for the pollutant of concern and are healthy at the start of the test. Species vary greatly in tolerance; for example, mayfly larvae indicate clean water, while sludge worms tolerate high pollution [2].

- Step 2: Standardize Experimental Conditions. Closely control and monitor water quality parameters, as they can influence toxicity. Key parameters to check include:

- Step 3: Verify Endpoint Measurement. For acute toxicity tests like LC50 (lethal concentration for 50% of test organisms) and EC50 (effective concentration for 50%), ensure the exposure duration (e.g., 96 hours for LC50) is strictly followed and that the endpoints (death, immobility) are consistently and accurately recorded [2].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What exactly are ecological indicators, and why are they significant? A1: Ecological indicators are measurable characteristics of an ecosystem that provide information about its condition, trends, or responses to environmental changes or stressors [3]. Their significance lies in simplifying complex ecological data, allowing policymakers, scientists, and managers to identify conservation priorities, monitor policy effectiveness, and anticipate emerging environmental issues [3].

Q2: What are the main types of ecological indicators? A2: Indicators can be broadly categorized as follows [3]:

| Type of Indicator | Characteristics | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Biological Indicators | Measure the presence, abundance, or health of specific species or communities. | Species population trends, community composition, biodiversity indices [3]. |

| Chemical Indicators | Measure the concentration of specific chemicals or pollutants in the environment. | Nutrient levels (e.g., nitrates), pH, heavy metal concentrations [3] [2]. |

| Physical Indicators | Measure physical properties of the environment. | Water temperature, sediment quality, habitat structure [3]. |

Q3: What are the common challenges when using indicator species? A3: Key challenges and pitfalls include [2]:

- Oversimplification: Judging an ecosystem's health based on a single indicator species may not be sufficient.

- Correlation vs. Causation: It can be difficult to ensure a scientifically sound link between the indicator and the environmental condition.

- Survey Difficulty: Some indicator species can be time-consuming or difficult to identify and monitor effectively.

Q4: What is the difference between 'LC50' and 'EC50' in ecotoxicity testing? A4: Both are measures of toxicity [2]:

- LC50 (Lethal Concentration 50): This is the concentration of a substance that is lethal to 50% of the test organisms within a specified time, typically 96 hours for acute tests.

- EC50 (Effective Concentration 50): This is the concentration that causes a specific, non-lethal effect (e.g., immobility, loss of fertility) in 50% of the test population.

Q5: Which new European EIV system is recommended for pan-European studies? A5: The Ecological Indicator Values for Europe (EIVE) 1.0 is a comprehensive system designed for this purpose. With indicator values for 14,835 vascular plants, it offers broader taxonomic and geographic coverage than many regional systems and has been shown to provide excellent performance in predicting site conditions like soil pH and temperature [1].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol: Calculating and Validating Mean Ecological Indicator Values (EIVs)

Purpose: To assess site conditions (e.g., soil pH, moisture, temperature) using the flora present in a vegetation plot.

Principle: The mean EIV for a site is calculated from the individual EIVs of all plant species present, based on the concept that the plant community composition reflects the integrated environmental conditions of that site [1].

Materials:

- Dataset of vegetation plots (species occurrence and/or cover data).

- A calibrated EIV system (e.g., EIVE 1.0 database).

- Statistical software (e.g., R, Python).

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Compile your list of species recorded in the vegetation plot. Taxonomically match species names to the EIV system being used.

- EIV Assignment: Assign the relevant EIV (e.g., for soil pH) to each species from the chosen EIV system.

- Calculate Mean EIV: Calculate the mean indicator value for the plot. Research suggests using an unweighted mean (presence/absence of species) is effective [1]. The formula is: ( E = \frac{\sum{i=1}^{n} xi}{n} ) Where ( E ) is the mean ecological indicator, ( x_i ) is the EIV of the ( i^{th} ) species, and ( n ) is the number of species with an EIV in the plot.

- Validation: Validate the calculated mean EIV by correlating it (e.g., using Pearson's correlation coefficient) with directly measured environmental parameters from the same plots [1].

Protocol: Conducting an Acute Aquatic Toxicity Test (LC50)

Purpose: To determine the concentration of a chemical that is lethal to 50% of a test population of aquatic organisms under defined conditions.

Principle: Test organisms are exposed to a range of concentrations of the test chemical for a fixed period (e.g., 96 hours). Mortality is recorded, and the LC50 is calculated statistically [2].

Materials:

- Test Organisms: Healthy, same-age juveniles or adults of a standard species (e.g., Daphnia magna, fathead minnow).

- Test Chemical: Stock solution of known concentration.

- Dilution Water: Clean, dechlorinated water with known pH, hardness, and alkalinity.

- Test Chambers: Glass or plastic containers of sufficient volume.

- Aeration System: To maintain dissolved oxygen.

- Water Quality Kits: For measuring temperature, pH, and dissolved oxygen.

Procedure:

- Acclimation: Acclimate test organisms to the test conditions for at least 48 hours.

- Range-Finding Test: Perform a preliminary test with a wide range of concentrations to determine the approximate LC50.

- Definitive Test: Prepare a geometric series of at least five test concentrations and a control. Randomly assign organisms to each chamber.

- Exposure & Monitoring: Expose organisms for 96 hours. Do not feed during the test. Monitor and record water quality (temperature, pH, DO) daily.

- Data Recording: Record the number of dead organisms in each chamber at 24, 48, 72, and 96 hours. Define death operationally (e.g., lack of movement upon gentle prodding).

- Data Analysis: Calculate the LC50 value with 95% confidence limits using an appropriate statistical method (e.g., Probit analysis, Spearman-Karber method).

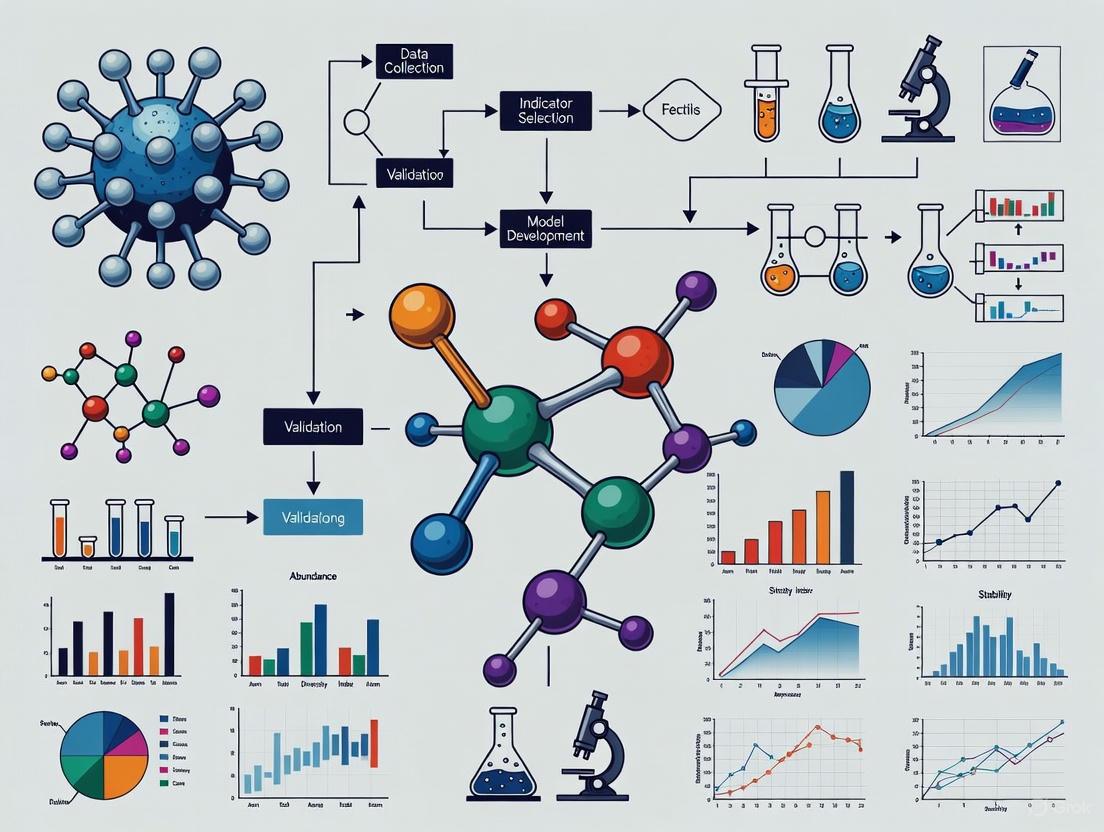

Workflow Visualization: Ecological Indicator Development and Application

Ecological Indicator Application Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table: Essential Materials for Ecological Indicator Research

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| EIV Database (e.g., EIVE 1.0) | Provides standardized ecological indicator values for vascular plant species, enabling the assessment of site conditions based on vegetation surveys [1]. |

| Standard Test Organisms (e.g., Daphnia, Fathead Minnow, Freshwater Shrimp) | Used in controlled aquatic toxicity tests (LC50/EC50) to determine the biological impact and safe levels of pollutants [2]. |

| Water Quality Probe (Measures DO, pH, Temperature, Conductivity) | Essential for monitoring and maintaining standardized conditions in aquatic experiments and for using these parameters as chemical/physical indicators of ecosystem health [2]. |

| Lichens and Mosses | Act as sensitive biological indicators (bioindicators) for air quality and heavy metal pollution, as they absorb nutrients and contaminants directly from the atmosphere [2]. |

| Benthic Macroinvertebrates (e.g., Mayfly, Stonefly, and Caddisfly Larvae) | Used in stream and river health assessments. The presence/absence and diversity of these organisms are key biological indicators of water pollution levels [2]. |

FAQs: Core Concepts and Troubleshooting

Q1: What precisely is an indicator species, and what defines a good one? An indicator species is an organism whose presence, absence, abundance, or physiological health provides information about the condition of an ecosystem or a specific environmental factor [4]. Good indicator species are characterized by [5] [4] [6]:

- Specificity: They exhibit a strong, predictable response to a particular environmental stressor (e.g., a pollutant).

- Sensitivity: They are sensitive to changes in the environmental condition they indicate, providing an early warning.

- Commonness and Ease of Identification: They should be common enough to be found and easily recognizable by field technicians, allowing for widespread monitoring without highly specialized training.

Q2: Our monitoring program uses a standard list of indicator species. Why are we getting unreliable results in our estuary? This is a common challenge. The core issue is that species' tolerances and preferences are not static; they can change along environmental gradients like salinity, temperature, or between different biogeographic regions [6]. A species considered "tolerant" in one sea might behave as "sensitive" in another. Troubleshooting Steps:

- Audit Your Species List: Verify that the indicator values for your species are calibrated for your specific region and habitat type (e.g., estuarine vs. open ocean).

- Check for Confounding Factors: Analyze if natural environmental gradients (e.g., a strong salinity gradient in your estuary) are influencing the species' response more than the target pollutant. What appears to be a pollution signal might be a natural response.

- Recommendation: Move towards a multi-metric approach that uses a suite of species or a biotic index, which is more robust than relying on a single static species list [5].

Q3: We need to monitor a large, remote forest for air quality. What is the most efficient method? For large-scale air quality monitoring, lichen biomonitoring is a highly efficient and established method [5] [4]. Lichens are particularly effective because they absorb nutrients and pollutants directly from the air.

- Protocol Outline:

- Site Selection: Establish a grid or transect system across the forest area.

- Data Collection: At each sampling point, record the following:

- Lichen Diversity: Identify and count the number of lichen species present.

- Percent Cover: Estimate the area of the tree bark or rock surface covered by lichens.

- Morphotype Analysis: Note the abundance of specific lichen types (e.g., foliose, crustose), as certain forms are more sensitive to pollution than others [5].

- Analysis: A decline in diversity, cover, or the presence of sensitive morphotypes indicates poor air quality.

Q4: In aquatic toxicology, what is the difference between a bioindicator and a bioaccumulator? This is a critical distinction for ecotoxicology studies.

- Bioindicator: An organism whose health or population dynamics reflects ecosystem health. For example, the decline of a mayfly population indicates deteriorating water quality [7].

- Bioaccumulator: An organism that accumulates pollutants in its tissues from the environment, often at concentrations much higher than the surrounding water or sediment. They are used to detect and measure the presence of contaminants like heavy metals or pesticides [5]. Mussels and other bivalves are classic bioaccumulators used in "mussel watch" programs.

Q5: What are the key limitations of using indicator species in research? While powerful, the approach has constraints that must be considered in experimental design [5] [6] [7]:

- Lack of Universality: A species' indicative value is not always transferable across different regions or ecosystems.

- Oversimplification: A single species cannot represent the complexity of an entire ecosystem.

- Multiple Stressors: It can be difficult to disentangle the effects of a specific pollutant from other natural or anthropogenic stressors.

- Scale Dependency: An indicator valid for a large vertebrate may not reflect the status of insect or microbial communities.

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Validating a Species as a Bioindicator for a Novel Stressor

This workflow outlines the key stages and decision points in validating a new bioindicator species, from initial selection to final implementation.

Objective: To systematically determine if a candidate species reliably indicates exposure to a specific environmental stressor (e.g., a new chemical pollutant, temperature change).

Materials:

- Equipment for field collection (nets, traps, water samplers, GPS).

- Environmental monitoring equipment (e.g., YSI meter for water quality, air samplers).

- Laboratory aquaria/mesocosms with environmental control.

- Equipment for physiological/behavioral measurement (microscope, spectrophotometer, PCR machine for genetic analysis).

- Statistical analysis software (R, PRIMER, etc.).

Methodology:

- Field Correlation Studies:

- Sampling: Collect data on the abundance and health of the candidate species across a gradient of the stressor (e.g., from polluted to pristine sites).

- Environmental Data: Simultaneously, measure the concentration of the target stressor and other key environmental variables (pH, salinity, temperature) at each site [6].

- Analysis: Use multivariate statistics (e.g., Redundancy Analysis) to identify if the candidate species' distribution is significantly correlated with the stressor, after accounting for other environmental factors.

Controlled Laboratory Exposure:

- Acclimation: Acclimate healthy individuals of the candidate species to standard laboratory conditions.

- Exposure: Expose groups of individuals to a range of concentrations of the stressor, including a control group with zero exposure.

- Endpoint Measurement: Monitor and quantify specific biological endpoints at defined intervals. These can include:

- Molecular: Gene expression changes, metallothionein induction.

- Physiological: Growth rate, respiration rate, photosynthetic efficiency (for plants/algae).

- Behavioral: Feeding rate, avoidance behavior.

- Morphological: Developmental deformities.

Dose-Response Modeling: Analyze the laboratory data to establish a quantitative relationship between the stressor level and the magnitude of the biological response. This confirms a causal link.

Field Validation: Return to the field to test if the dose-response relationship observed in the lab holds true under natural conditions. This step verifies the species' utility as a real-world sentinel.

Protocol 2: Benthic Macroinvertebrate Survey for Water Quality Assessment

Objective: To assess the ecological health and water quality of a freshwater stream or lake using the benthic macroinvertebrate community.

Materials:

- D-frame kick net.

- White plastic tray.

- Fine-tipped forceps, pipettes.

- Sampling jars and preservative (e.g., 70% ethanol).

- Ice chest for temporary storage.

- Water quality test kit (for pH, dissolved oxygen, nitrates).

Methodology:

- Site Selection: Choose representative reaches of the stream (e.g., riffle areas where flow is turbulent).

- Sample Collection:

- Place the kick net firmly on the stream bed, facing upstream.

- Disturb the substrate (rocks, gravel) immediately upstream of the net for a standardized time (e.g., 3 minutes), allowing dislodged organisms to be carried into the net.

- Sample Processing:

- Transfer the contents of the net to a white tray partially filled with clean water.

- Use forceps and pipettes to pick out all macroinvertebrates (e.g., insect larvae, worms, crustaceans) and place them in a jar with preservative.

- Laboratory Analysis:

- Identify organisms to the finest practical taxonomic level (usually family or genus) using dichotomous keys.

- Count the number of individuals in each taxonomic group.

- Data Analysis and Interpretation:

Data Presentation: Quantitative Profiles of Common Indicator Species

Table 1: Characteristics and Applications of Common Bioindicator Species

| Indicator Species | Environmental Parameter Monitored | Type of Response Measured | Typical Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lichens [5] [4] | Air Quality (SO₂, NOx, Heavy Metals) | - Presence/Absence of sensitive species- Total lichen diversity- Morphotype community shifts | - Transect surveys on tree bark or rocks.- Analysis of pollutant concentrations in thallus. |

| Freshwater Frogs [5] [8] | Water Quality, Chemical Pollutants, UV Radiation | - Population decline- Morphological deformities (e.g., limb malformations)- Egg hatching success rate | - Field population censuses.- Laboratory Tadpole Assay (FET) for teratogenicity. |

| River Otter [5] | Health of Freshwater Ecosystems, Bioaccumulation of Mercury | - Population density and reproductive success- Tissue concentration of mercury and other contaminants | - Non-invasive surveys (camera traps, spraint analysis).- Post-mortem analysis of tissue contaminants. |

| Planktonic Communities [5] [4] | Trophic Status of Water Bodies, Eutrophication | - Chlorophyll-a concentration- Species composition shifts (e.g., diatom to cyanobacteria ratio)- Algal bloom formation | - Water sampling and microscopic analysis.- In vivo chlorophyll fluorescence measurement. |

| Polychaete Worms (e.g., Nereis diversicolor) [5] [6] | Marine Sediment Health, Organic Enrichment, Toxic Substances | - Abundance of opportunistic vs. sensitive species- Bioaccumulation of heavy metals in tissues | - Sediment core sampling and benthic community analysis.- Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy of worm tissues. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for Indicator Species Studies

| Item/Solution | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Later Stabilization Solution | Presves RNA integrity in tissue samples for gene expression studies (e.g., stress response gene analysis). | Critical for -80°C storage; prevents degradation during transport from field to lab. |

| Liquid Nitrogen | Flash-freezing tissue samples for metabolomic, proteomic, and transcriptomic analyses. | Preserves labile metabolites and RNA; requires safe handling and storage protocols. |

| Ethanol (70-95%) | Standard preservative for macroinvertebrate, benthic, and botanical specimens. | Concentration depends on specimen type; required for morphological identification. |

| Formalin Buffer Solution | Fixative for histological analysis of tissues (e.g., for detecting pathological changes). | Handling requires fume hood due to toxicity; being replaced by safer alternatives like ethanol. |

| ICP-MS Standard Solutions | Calibration for Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry to quantify heavy metals in bioaccumulator tissues. | Requires high-purity, element-specific standards for accurate quantification of trace metals. |

| DNA Extraction Kits (for eDNA) | Isolating environmental DNA from water, soil, or sediment samples to detect rare/elusive species [9]. | Allows detection without physical capture; kit choice depends on sample type and inhibitor load. |

| LSC Cocktail for Liquid Scintillation | Quantifying radiolabeled compound uptake in bioaccumulation studies. | For use with radioactive tracers (e.g., C-14, H-3); requires radiation safety protocols. |

| Fluorescent Dyes (e.g., DCFDA) | Measuring oxidative stress in cells/tissues as a sub-lethal response to pollutants. | Provides a quantitative measure of cellular health; requires a fluorescence plate reader. |

Conceptual Framework for Indicator Species in Ecological Assessment

This diagram illustrates the conceptual pathway from an environmental stressor to the measurable response in an indicator species, and how this informs ecological assessment and management.

Conceptual Soundness: Establishing a Robust Theoretical Foundation

What is conceptual soundness and why is it critical for ecological indicators?

Conceptual soundness refers to the logical coherence and theoretical justification for why a specific parameter should function as a reliable indicator. It ensures that the indicator accurately represents the ecological construct or process it is intended to measure, forming the bedrock of credible research. A conceptually sound indicator has a clear, defensible link to the ecosystem state it signifies, preventing misinterpretation of data and ensuring that management decisions are based on valid information [10].

How can I verify the conceptual soundness of an ecological indicator?

Verification involves multiple lines of inquiry, as detailed in the table below.

Table 1: Framework for Assessing Conceptual Soundness

| Assessment Question | Methodology | Example from Ecological Research |

|---|---|---|

| Is the ecological concept well-defined and relevant? | Conduct a comprehensive literature review and hold expert workshops to define the theoretical boundaries of the concept (e.g., "resilience," "health"). | Clearly defining "biodiversity" not just as species count, but including genetic, functional, and structural diversity [11]. |

| Is the indicator appropriate for the target population or ecosystem? | Perform cognitive interviews and focus groups with end-users and local experts to assess relevance and comprehension [12]. | Ensuring a forest integrity indicator is relevant to both tropical and boreal systems, adapting metrics as needed. |

| Is there evidence of reliability and validity? | Execute pilot studies to obtain preliminary estimates of reliability (test-retest, internal consistency) and assess score distributions and floor/ceiling effects [12]. | Testing if a benthic index shows consistent results when applied to the same set of samples at different times. |

| Does the indicator show responsiveness to change? | Analyze data from long-term monitoring or controlled experiments to confirm the indicator changes predictably in response to stressors or management actions. | Verifying that a macroinvertebrate index shifts accordingly with changes in water pollution levels. |

What are common pitfalls in establishing conceptual soundness?

A frequent pitfall is adopting indicators developed in one biogeographical or cultural context and applying them to another without testing for conceptual equivalence. An activity deemed meaningful in one ecosystem might be irrelevant in another, leading to a failure to detect important changes [12]. Another pitfall is a lack of clear causality; a correlation may exist, but without a understood mechanistic link, the indicator's value is questionable.

Feasibility: Ensuring Practical Viability in Research and Monitoring

What key areas should a feasibility assessment cover?

Feasibility extends beyond simple cost analysis. A comprehensive assessment, drawing from public health and behavioral science frameworks, should evaluate several key areas to determine if an indicator can be successfully implemented in practice [13].

Table 2: Key Focus Areas for Feasibility Assessment

| Area of Focus | The Feasibility Study Asks... | Sample Quantitative & Qualitative Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| Acceptability | To what extent is the indicator and its measurement method judged as suitable or attractive? | Satisfaction ratings; perceived appropriateness; intent to continue use; feedback from stakeholders [13]. |

| Implementation | To what extent can the indicator be measured successfully as planned in a real-world context? | Degree of execution success; resources required (time, personnel); factors affecting ease/difficulty [13]. |

| Practicality | To what extent can the measurement be carried out with existing means, resources, and circumstances? | Ability of field crews to follow protocols; completion rates and times for measurements; perceived burden [12] [13]. |

| Integration | To what extent can the indicator be integrated within an existing monitoring system? | Perceived fit with infrastructure; costs to the organization; fit with organizational goals [13]. |

What quantitative metrics can I use to evaluate feasibility?

Pilot studies are essential for collecting quantitative feasibility data. Key indicators include [12]:

- Recruitment Rate: The number and percentage of target sites or subjects that agree to participate.

- Retention Rate: The proportion of sites or subjects that remain in the monitoring program until completion.

- Data Completion Rate: The percentage of data points successfully collected versus those planned.

- Protocol Adherence: The extent to which field staff or automated systems correctly follow the defined measurement protocols.

- Cost and Time Metrics: Average cost per sample and time required for collection, processing, and analysis.

How do I design a pilot study for feasibility testing?

Design a small-scale study that mirrors the protocols of the future large-scale study as closely as possible. The primary goal is to field-test logistical aspects, not to test ecological hypotheses [12]. Use a combination of quantitative methods (e.g., tracking recruitment and completion rates) and qualitative methods (e.g., semi-structured interviews with field technicians about challenges) to gather comprehensive feasibility data. This mixed-methods approach identifies not just if a protocol fails, but why [12].

Response Variability: Quantifying and Accounting for Noise

Understanding and partitioning the sources of variability is crucial to distinguish true ecological change from background noise. The main sources include:

- Natural Spatial Variability: Inherent patchiness and heterogeneity in the environment.

- Natural Temporal Variability: Changes due to diel, seasonal, and inter-annual cycles.

- Sampling Variance: Error introduced by the process of measuring, sub-sampling, and analyzing samples.

- Observer Bias: Differences in how measurements are taken or organisms are identified by different individuals.

What experimental protocols minimize unwanted variability?

Employ rigorous, standardized protocols:

- Stratified Random Sampling: Design surveys to capture known environmental gradients explicitly, rather than assuming homogeneity.

- Calibration and Training: Regularly calibrate instruments and conduct inter-observer calibration exercises to ensure consistency among different technicians [12].

- Blinded Protocols: Where possible, have technicians process samples without knowledge of the treatment group or site status to reduce subconscious bias.

- Quality Control Replicates: Incorporate field blanks, lab replicates, and positive controls into the sampling design to quantify measurement error.

How is response variability analyzed and reported?

The core tool for analysis is variance components analysis, which statistically partitions the total observed variance into its constituent sources (e.g., spatial, temporal, measurement error). Furthermore, confidence intervals should always be reported around estimates of effect sizes, adherence rates, or indicator values. With small pilot samples, these intervals will be large, providing a more honest representation of the uncertainty and preventing overconfidence in preliminary results [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Indicator Development and Testing

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Standardized Field Collection Kits | Ensures consistency in sample collection (e.g., water, soil, benthic organisms) across different teams and time points, reducing sampling variance. |

| Preservative and Fixative Solutions | (e.g., RNA later, DMSO buffer, formalin). Maintains the integrity of biological samples from the moment of collection until lab analysis, critical for genetic, microbiological, and taxonomic indicators. |

| Calibration Standards and Blanks | Essential for quality control of chemical and physical analyses (e.g., nutrient assays, sensor readings). Used to create standard curves and account for background contamination or instrument drift. |

| Primers and Probes for eDNA/barcoding | Allows for the identification of species and functional genes from environmental samples, forming the basis for modern molecular ecological indicators. |

| Reference Samples and Vouchers | A curated collection of verified specimens or samples used to train staff and validate taxonomic identifications or chemical fingerprints, ensuring long-term data consistency. |

Workflow Visualization: Ecological Indicator Assessment

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the primary advantages of using biotic indicators over traditional physicochemical water quality assessments?

Biotic indicators provide a time-integrated measure of environmental health, reflecting the cumulative effects of both short- and long-term pollution events and habitat degradation. Unlike instantaneous chemical measurements, the structure of biological communities captures impacts on living organisms and reveals the ecological consequences of stressors, making it a more comprehensive tool for assessing ecosystem integrity [14] [15] [16].

2. How do I select the most appropriate taxonomic group and specific metrics for my bioassessment study?

The choice depends on your study's specific objectives, the type of ecosystem, and the stressors of interest. A multi-taxa approach is often most robust. For general water quality and organic pollution, macroinvertebrates are a standard choice, with metrics like the EPT index (Ephemeroptera, Plecoptera, Trichoptera) being highly sensitive [17] [14] [15]. Algae, particularly diatoms, are excellent indicators of nutrient enrichment and rapid changes in water chemistry [16]. Fish are ideal for assessing broader ecosystem health, including habitat structure and food web dynamics, over larger spatial scales [18].

3. What is a key taxonomic challenge when working with macroinvertebrates, and how can it be addressed?

A significant challenge is the level of taxonomic identification. While identification to genus or species is most sensitive, it requires extensive expertise and time. Identification to the family level often provides a reliable compromise for detecting water quality gradients, though the required resolution depends on the program's goals [14] [15] [19]. Emerging solutions include using DNA barcoding to improve accuracy and efficiency [20] [19].

4. My biomonitoring results show a degraded community. How can I troubleshoot the specific cause?

A depressed biotic index score indicates a problem but does not diagnose the cause. Follow these steps:

- Correlate with Habitat Assessment: A poor score coupled with poor habitat ratings (e.g., eroded banks, lack of substrate) strongly suggests habitat degradation is the primary stressor [14].

- Correlate with Water Chemistry: Check for anomalies in dissolved oxygen, nutrients, pH, or specific contaminants. For example, low dissolved oxygen often eliminates sensitive stonefly and mayfly larvae [14].

- Analyze the Community Composition: A community dominated by pollution-tolerant taxa like aquatic worms (Oligochaeta) and certain midges (Chironomidae) indicates organic pollution [15]. The loss of specific functional feeding groups can also provide clues.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental and Field Challenges

| Challenge | Possible Causes | Solutions & Checks |

|---|---|---|

| Low Taxonomic Diversity | Pollution Impact: Chemical pollutants (organic, toxic).Habitat Loss: Poor substrate, sedimentation.Natural Variability: Seasonality, inappropriate reference site. | - Conduct concurrent water chemistry and habitat surveys [14].- Use ecoregion-specific reference conditions for comparison [18].- Sample across multiple seasons to account for natural cycles [19]. |

| High Variability Between Replicates | Inconsistent Sampling: Technique, effort, or habitat.Patchy Distribution: Natural invertebrate aggregation.Improper Sample Processing. | - Implement standardized, proven protocols (e.g., EPA Rapid Bioassessment Protocols) [14].- Collect a sufficient number of replicates (e.g., 3+ fyke nets for fish) [18].- Implement quality control via expert review of specimen identifications [21]. |

| Inability to Detect Expected Trends | Insufficient Statistical Power: Low sample size.Incorrect Taxonomic Resolution: Identifying to too coarse a level.Mismatched Indicator and Stressor. | - Conduct a power analysis before study design [21].- Increase identification resolution (e.g., from order to family) [14] [15].- Ensure selected indicator group is sensitive to target stressor [16] [18]. |

| Difficulty Identifying Specimens | Lack of Regional Keys: Inadequate taxonomic resources.Damaged Specimens: Improper preservation/handling. | - Use DNA barcoding to confirm difficult taxa [20] [19].- Preserve specimens immediately in appropriate agents (e.g., ethanol) [14]. |

Table 1: Summary of the primary biotic indicator groups, their applications, and standardized metrics.

| Indicator Group | Key Advantages | Common Metrics & Indices | Typical Taxonomic Level | Sensitive To |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Algae (esp. Diatoms) | - Rapid reproduction reflects short-term changes [16].- Direct response to nutrients [16].- Easy sampling, cost-effective [16]. | - Diatom Index [16].- Palmer's Algal Index [16].- Species Diversity [16]. | Species / Genus | Nutrient enrichment, pH, organic pollution, toxicants. |

| Benthic Macroinvertebrates | - Integrate conditions over time [17] [14].- Sedentary nature pinpoints pollution source [14].- Well-established protocols [14] [21]. | - EPT Index [14] [15] [19].- Hilsenhoff Biotic Index [19].- BMWP/ASPT [15]. | Family / Genus | Dissolved oxygen, sedimentation, organic pollution, habitat degradation. |

| Fish | - Reflect health of entire watershed [18].- Long-lived, indicate chronic effects [18].- High public and economic value [18]. | - Index of Biotic Integrity (IBI) [18].- Species Richness & Composition [18].- Trophic Composition [18]. | Species | Habitat fragmentation, flow regime, chemical pollution, trophic structure. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Streamside Biosurvey for Benthic Macroinvertebrates This protocol is adapted from the EPA's tiered framework for volunteer monitoring and is ideal for problem identification and screening [14].

- Site Selection & Habitat Assessment: Select a representative riffle area. Before sampling, conduct a habitat assessment evaluating bank stability, channel alteration, riparian vegetation, and substrate type [14].

- Sample Collection: Using a D-frame kick net, place the net securely on the stream bottom with the opening facing upstream. Disturb the substrate for a set time (e.g., 3 minutes) and distance (e.g., 1 meter) upstream of the net, allowing the flow to carry dislodged organisms into the net [14].

- Field Processing: Transfer the sample to a white pan with clean water. Using forceps, sort macroinvertebrates live into broad taxonomic orders (e.g., Ephemeroptera, Plecoptera, Trichoptera, Diptera, Oligochaeta). This can be done visually or with a hand lens [14].

- Data Analysis & Interpretation: Categorize collected organisms into sensitivity groups (e.g., pollution-sensitive, somewhat sensitive, tolerant). Calculate a simple index score based on the abundance and diversity of these groups to provide a preliminary ranking of site quality [14].

Protocol 2: Laboratory-Based Intensive Biosurvey This more rigorous protocol requires microscopy and professional supervision, yielding data suitable for trend analysis and regulatory reporting [14].

- Sample Collection & Preservation: Collect composite benthic samples from multiple habitats (e.g., riffles, pools, snags) using appropriate gear (e.g., Surber samplers, kick nets, or grab samplers) [14] [19]. Immediately preserve the entire sample in a labeled container with 70-95% ethanol.

- Laboratory Processing: In the lab, spread the sample in a gridded tray and systematically pick out all macroinvertebrates under a dissecting microscope.

- Taxonomic Identification: Identify specimens under a microscope to the family level (or genus where possible) using dichotomous keys specific to your ecoregion. A quality control step, where a second taxonomist verifies a subset (e.g., 10%) of identifications, is critical [21].

- Multimetric Data Analysis: Calculate a suite of metrics, which may include:

- Richness Measures: Total taxa, EPT taxa richness.

- Composition Metrics: % of Dominant taxon, % EPT.

- Tolerance Metrics: Hilsenhoff Biotic Index, Average Score Per Taxon (ASPT). These metrics are then combined into a multimetric index (e.g., an Index of Biotic Integrity) and compared to reference site conditions to assess ecological health [14] [15] [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key equipment and reagents required for establishing a biomonitoring program.

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| D-frame Kick Net | Standardized collection of benthic macroinvertebrates in wadable streams with rocky substrates [14]. |

| Fyke Nets | Passive capture of fish assemblages in wetland and littoral zone habitats; used in vegetation-stratified sampling [18]. |

| Surber Sampler | Quantitative sampling of macroinvertebrates in stream riffles; provides a defined area and downstream collection [19]. |

| Ethanol (70-95%) | Standard preservative for macroinvertebrate and fish samples; prevents decomposition and maintains integrity for identification [14]. |

| Dissecting Microscope | Essential for accurate sorting and identification of macroinvertebrates to family or genus level in the laboratory [14] [19]. |

| Diatom Sampling Substrate | Artificial substrates (e.g., glass slides) or natural rocks for collecting periphyton diatom communities for water quality inference [16]. |

| Water Quality Multiprobe | For concurrent measurement of key physicochemical parameters (e.g., dissolved oxygen, pH, conductivity, temperature) to correlate with biological data [15] [21]. |

| Regional Taxonomic Keys | Specialized guides for identifying aquatic organisms to the required taxonomic level (species, genus, family) within a specific geographic area [14]. |

Experimental Workflow for Biotic Indicator Development

The diagram below outlines the logical workflow for developing and testing a biotic index, such as an Index of Biotic Integrity (IBI).

Biotic Index Development Workflow

Field Sampling Design for Habitat-Stratified Assessment

The diagram below illustrates a stratified sampling approach for complex habitats, such as coastal wetlands, where vegetation type significantly influences community composition.

Habitat-Stratified Sampling Design

The continuous release of pharmaceutical residues into aquatic environments represents a significant threat to ecosystem health and stability. These pharmaceutical contaminants, originating from human and veterinary medicine, enter water bodies through various pathways, including wastewater effluent, agricultural runoff, and improper medication disposal [22] [23]. Unlike traditional pollutants, pharmaceuticals are specifically designed to be biologically active at low concentrations, making them particularly concerning for non-target aquatic organisms [24]. Their pseudo-persistent nature, due to continuous input and incomplete removal by conventional wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs), creates chronic exposure scenarios for aquatic life [22] [25]. This technical guide addresses the key challenges in monitoring these pollutants and provides troubleshooting support for researchers developing ecological indicators for aquatic ecosystem assessment.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 1: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Pharmaceutical Pollutant Analysis

| Item Name | Type/Category | Primary Function in Analysis | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oasis HLB Cartridges | Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) Sorbent | Extraction and pre-concentration of diverse pharmaceuticals from aqueous samples | Method development for 18 pharmaceuticals and 3 TPs in seawater [25] |

| Isotopically Labelled Internal Standards (ILIS) | Analytical Standards | Correction for matrix effects and quantification accuracy during mass spectrometry | Carbamazepine-d10, fluoxetine-d5 for UHPLC-HRMS analysis [25] |

| UHPLC-MS/MS Grade Solvents | Solvents/Reagents | High-purity mobile phase components to minimize background noise and ion suppression | Methanol and water for UHPLC-MS/MS analysis [26] [25] |

| Certified Pharmaceutical Standards | Analytical Standards | Method calibration, identification, and quantification of target analytes | Carbamazepine, ibuprofen, caffeine for method validation [26] |

| LC-HRMS/Orbitrap System | Instrumentation | High-resolution accurate-mass measurement for identification and quantification | UHPLC-LTQ/Orbitrap MS for multiclass pharmaceutical detection [25] |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Analytical Challenges

Low Analytical Sensitivity and Recovery

Problem: Inability to detect pharmaceuticals at environmentally relevant concentrations (ng/L).

- Potential Cause 1: Inefficient sample pre-concentration or excessive sample loss during Solid Phase Extraction (SPE).

- Solution: Optimize the SPE protocol. Test different sorbent types (e.g., Oasis HLB, C18). The Oasis HLB cartridge has demonstrated high recoveries (61.6%–118.8%) for a wide range of pharmaceuticals in seawater [25]. Ensure sample pH is adjusted prior to loading and use appropriate elution solvents.

- Potential Cause 2: Inadequate instrument detection limits.

- Solution: Employ tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) in Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) mode. This provides significantly higher sensitivity and selectivity compared to UV or single-stage MS detection. UHPLC-MS/MS can achieve limits of detection as low as 100 ng/L for compounds like carbamazepine [26].

Matrix Interferences in Complex Samples

Problem: Signal suppression or enhancement caused by co-extracted compounds from complex environmental matrices (e.g., wastewater, seawater).

- Potential Cause: The sample matrix contains salts, organic matter, or other contaminants that interfere with the ionization of target analytes.

- Solution:

- Use Isotopically Labelled Standards: Add ILIS (e.g., carbamazepine-d10) before extraction. These standards correct for matrix effects and losses during sample preparation [25].

- Improve Chromatographic Separation: Utilize Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (UHPLC) to enhance peak resolution and separate analytes from interferences.

- Dilute and Re-inject: If contamination is severe, dilute the sample extract and re-analyze to reduce the matrix concentration.

Challenges in Biomarker-Based Ecotoxicology

Problem: High variability in physiological biomarker responses (e.g., enzyme activities) in exposed organisms.

- Potential Cause 1: Uncontrolled environmental or husbandry factors (temperature, diet, stress) influencing the biochemical endpoints.

- Solution: Strictly standardize acclimation and exposure conditions. Maintain stable water quality parameters (temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen) and use a controlled diet throughout the experiment [24].

- Potential Cause 2: Inappropriate biomarker selection for the target pharmaceutical.

- Solution: Base biomarker selection on the known mode of action. For neuroactive drugs (e.g., bromazepam), measure acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and monoamine oxidase (MAO) activities in brain tissue. For contaminants causing oxidative stress, analyze antioxidant response elements [24].

Experimental Protocols for Indicator Development

Protocol: Multi-Residue Analysis of Pharmaceuticals in Water

Method: Off-line Solid Phase Extraction followed by UHPLC-High Resolution Mass Spectrometry [25].

Workflow Overview:

Detailed Steps:

- Sample Collection and Preservation: Collect water samples in pre-cleaned containers. Filter immediately through 0.45 μm membrane filters (e.g., Millipore) to remove suspended solids. Store samples at -20°C until extraction to prevent degradation.

- Solid Phase Extraction:

- Condition Oasis HLB cartridges (200 mg, 6 mL) with 5-10 mL of methanol followed by 5-10 mL of reagent water.

- Load a known volume of filtered water sample (e.g., 100-1000 mL) onto the cartridge at a steady flow rate (e.g., 5-10 mL/min).

- Dry the cartridge under vacuum for ~15-30 minutes to remove residual water.

- Elute target analytes with 2 x 5-10 mL of an appropriate organic solvent (e.g., methanol or acetonitrile).

- Concentration and Reconstitution: Gently evaporate the eluate to dryness under a stream of nitrogen gas. Reconstitute the dry extract in a small volume (e.g., 100-200 μL) of methanol/water (e.g., 10/90, v/v) compatible with the LC mobile phase.

- UHPLC-HRMS Analysis:

- Chromatography: Use a C18 UHPLC column with a gradient elution program. Mobile phase A is often water with 0.1% formic acid, and phase B is methanol or acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid. A typical short run time is around 10 minutes [26].

- Detection: Operate the HRMS (e.g., Orbitrap) in positive electrospray ionization (ESI+) mode. Use full-scan/data-dependent MS2 (dd-MS2) for non-target screening or parallel reaction monitoring (PRM) for targeted quantification.

Validation Parameters:

- Linearity: Correlation coefficient (R²) ≥ 0.991 [25].

- Precision: Relative Standard Deviation (RSD) for intra-day and inter-day precision < 5% [26] [25].

- Accuracy: Recovery rates typically between 70-120% [26] [25].

- Limits of Quantification (LOQ): Method should achieve LOQs in the ng/L range (e.g., 1.2 ng/L for carbamazepine) [25].

Protocol: Assessing Sub-Leththal Effects in Aquatic Bioindicators

Method: Histopathological and Neurological Biomarker Analysis in Fish [24].

Workflow Overview:

Detailed Steps:

- Test Organism and Acclimation: Use a standardized bioindicator species such as Common carp (Cyprinus carpio). Acclimate fish to laboratory conditions for a minimum of two weeks in dechlorinated, aerated water with controlled temperature (e.g., 25 ± 2°C), pH (7-8), and hardness, while providing a standard diet [24].

- Exposure Experiment: Expose fish to environmentally relevant concentrations of the target pharmaceutical(s) via waterborne exposure. Include a control group and multiple exposure concentrations. A typical exposure duration is 15 days, with daily monitoring of water quality and fish health.

- Tissue Sampling: After the exposure period, euthanize fish humanely and dissect to collect relevant tissues (e.g., brain, liver, kidney, gills).

- Biomarker Analysis:

- Neurological Markers: Homogenize brain tissue. Assess acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and monoamine oxidase (MAO) activities using standardized spectrophotometric or fluorometric assays. A significant reduction indicates neurotoxic effects [24].

- Immunological Markers: Analyze pro-inflammatory cytokines like Interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and Interleukin-6 (IL-6) in tissue homogenates or plasma using ELISA kits to identify inflammatory responses.

- Histopathological Examination: Preserve tissues (e.g., liver, kidney) in neutral buffered formalin. Process, embed in paraffin, section, and stain with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E). Examine slides under a light microscope for tissue alterations such as necrosis, inflammation, and fatty degeneration.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Which pharmaceuticals are considered priority indicators for monitoring aquatic pollution? A1: Key indicator pharmaceuticals include carbamazepine (an anticonvulsant, due to its high persistence), caffeine (a marker for domestic wastewater), and ibuprofen (a common NSAID) [26]. The revised EU Urban Wastewater Treatment Directive also lists diclofenac, venlafaxine, citalopram, and several antibiotics as substances for mandatory monitoring, providing a regulatory-based priority list [27].

Q2: Our analytical method lacks sensitivity for trace-level detection. What is the most effective upgrade path? A2: Transitioning to LC-MS/MS is the most effective upgrade. It is considered the gold standard for this application, offering superior sensitivity (LODs in the ng/L range), high selectivity via MRM, and the ability to confirm analytes based on specific fragmentation patterns, thereby minimizing matrix interferences [26]. Incorporating an SPE pre-concentration step that omits solvent evaporation can also enhance sensitivity while aligning with Green Analytical Chemistry principles [26].

Q3: What are the critical effects of pharmaceutical pollutants on aquatic organisms? A3: Effects are diverse and can occur at low concentrations:

- Neurological & Behavioral: Disruption of neurotransmitter systems (e.g., inhibited AChE activity) [24].

- Immunological: Induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-1β, IL-6), leading to chronic stress [24].

- Histopathological: Damage to vital organs like liver and kidney [24].

- Ecological: Contribution to antibiotic resistance (e.g., from azithromycin) and endocrine disruption, which can impact reproduction and population dynamics [22] [23].

Q4: How can we make our monitoring methods more sustainable ("green")? A4: Adopt the principles of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC). Key strategies include:

- Reducing Solvent Use: Eliminate or reduce evaporation steps in SPE [26].

- Shortening Analysis Time: Utilize fast UHPLC gradients (e.g., 10-minute runs) [26].

- Miniaturizing Methods: Explore micro-extraction techniques.

- Using Less Hazardous Chemicals: Choose safer solvents where possible. These approaches minimize environmental impact while maintaining high-quality results [26].

Q5: What are the biggest knowledge gaps in current research? A5: Critical gaps include:

- The environmental fate and long-term ecotoxicity of understudied but widely used pharmaceuticals like azithromycin, dexamethasone, and prednisone [23].

- The ecological impact of transformation products (TPs) generated from parent pharmaceuticals [23] [25].

- The effects of complex mixtures of pharmaceuticals and other contaminants (e.g., microplastics) on aquatic ecosystems [22].

- Long-term sublethal exposure data and the resulting ecological risks [23].

From Data to Decisions: Methodological Approaches for Indicator Implementation

Statistical Tools for Assemblage Data Analysis

The analysis of assemblage data, common in ecological indicator research, requires specialized statistical tools to handle complex, multi-species datasets. The table below summarizes key software options suitable for processing assemblage data, particularly in contexts like diatom assessment or other bioindicator studies.

Table 1: Statistical Software for Assemblage Data Analysis

| Software Tool | Primary Use Case | Key Features for Assemblage Data | Usage Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| R Foundation [28] [29] | General statistical analysis, data mining, and custom metric development | Extensive packages for multivariate statistics, community ecology, and data visualization; highly customizable for novel indices [30]. | Free and open-source; requires coding knowledge; steep learning curve [29]. |

| PRIMER (Not listed in results) | Community ecology & multivariate analysis | Specialized for similarity percentages, ordination, and analyzing species abundance data. | (Information from external knowledge) |

| SPSS [28] [29] | Social science research & general statistical analysis | User-friendly GUI; can compile descriptive statistics and perform parametric/non-parametric analyses [29]. | Less specialized for ecology; good for beginners; can automate analysis with scripts [28]. |

| GraphPad Prism [28] [29] | Biology-focused statistics | Versatile statistical capabilities; publication-worthy graphs; intuitive GUI for most tasks [29]. | Ideal for biologists; may lack advanced multivariate methods. |

| PC-ORD (Not listed in results) | Multivariate analysis of ecological data | Comprehensive suite of ordination and clustering methods designed explicitly for ecological communities. | (Information from external knowledge) |

| XLSTAT [28] [29] | Data mining & multivariate analysis in Excel | Excel add-on; provides tools for data visualization, descriptive statistics, and regression analysis [29]. | Good for users already familiar with Excel; enhances native capabilities [28]. |

Simplification and Dimensionality Reduction Techniques

Assemblage data often contains a high number of variables (e.g., species), making simplification a crucial step before analysis. The following techniques help reduce dimensionality and identify underlying patterns.

Table 2: Data Simplification and Analysis Techniques

| Technique | Primary Purpose | Application in Assemblage Studies | Key Concepts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster Analysis [31] [30] | Group similar objects based on characteristics | Identify groups of similar samples or sites based on species composition. | K-means, Hierarchical Clustering; groups data points based on similarities [30]. |

| Factor Analysis [31] | Identify underlying latent variables | Reduce many correlated species into a few underlying environmental gradients. | Exploratory/Confirmatory Factor Analysis; simplifies datasets into fewer dimensions called factors [31]. |

| Principal Component Analysis (PCA) [30] | Reduce dimensionality while preserving variance | Visualize and summarize the main patterns in species assemblage data. | A type of dimensionality reduction; finds linear combinations of features capturing the most variance [30]. |

| Metric Development [32] | Create tailored indices for specific methods | Develop new, method-specific metrics (e.g., for DNA metabarcoding data) that mirror traditional indices. | Recalibrate existing indices for new data types; essential when method differences cause bias [32]. |

Experimental Workflow for Assemblage Data Processing

The diagram below outlines a generalized protocol for processing and analyzing assemblage data, from raw data to ecological interpretation. This workflow is critical for ensuring reproducible research in ecological indicator development.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How do I handle the major differences in data structure between traditional microscopy and modern high-throughput sequencing (HTS) methods?

Fundamental differences in the nature of assemblage data generated by different methods (e.g., light microscopy vs. DNA metabarcoding) mean that using metrics designed for one method on another can give biased results [32]. The proportions of key species often differ significantly between methods.

- Recommended Approach: Do not simply apply correction factors. Instead, recalibrate existing indices or develop new metrics specifically designed for the new data type. For instance, a Trophic Diatom Index can be recalibrated for HTS data to maintain sensitivity to nutrient pressures while acknowledging that perfect agreement with the original method is unlikely [32].

- Expected Outcome: While correlation between well-calibrated metrics from different methods can be good (e.g., r = 0.86), a significant proportion of sites (e.g., 30%) may still change ecological status class. This necessitates informed discussion about the benefits and challenges of new methodologies [32].

My dataset has many rare species. Should I remove them before analysis?

Rare species can introduce noise, but their removal should be a justified, documented decision, not an automatic step.

- Guidance: Conduct a sensitivity analysis. Run your core analysis (e.g., ordination, index calculation) twice: once with the full dataset and once with rare species removed (e.g., species occurring in fewer than 5% of samples or with very low abundance).

- Decision Point: If the overall interpretation of the main patterns or the site rankings do not change significantly, removing rare species can simplify the model and highlight stronger signals. If results change drastically, this indicates that rare species may be important bioindicators in your system and should be investigated further or retained.

What is the best way to visualize complex assemblage data for a scientific publication?

Effective visualization is key to communicating complex data. Adhere to the following best practices:

- Choose the Right Chart: For assemblage data, ordination plots (e.g., PCA, NMDS), heatmaps, and bar charts of indicator species are most common [33].

- Maximize Data-Ink Ratio: Remove unnecessary chart borders, backgrounds, and redundant labels. Make gridlines light gray or remove them if exact values are not critical. Use direct labeling on chart elements instead of legends where possible [33].

- Use Color Strategically and Accessibly:

- Use a limited palette (5-7 distinct colors) to avoid overwhelming the reader [33].

- Ensure high contrast between elements and the background [34].

- Do not rely on color alone. Use different shapes, patterns, or textures to distinguish groups, ensuring the visualization is interpretable for those with color vision deficiencies [35].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Statistical model fails to converge or produces unreliable results.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Data Not Properly Scaled | Check the range of values for different species. Is there a mix of very large and very small numbers? | Apply data transformation (e.g., log(x+1), square root) or standardization (e.g., converting to z-scores) to make variables comparable [30]. |

| Too Many Variables (Species) | The number of species may be exceeding the number of samples. | Apply dimensionality reduction techniques (e.g., PCA, Factor Analysis) to reduce the number of variables before proceeding with further analysis [31] [30]. |

| Excessive Zero Inflation | A high proportion of zeros in the species count data can disrupt many statistical models. | Consider using statistical methods specifically designed for zero-inflated data (e.g., zero-inflated models) or simplify the dataset by aggregating species or sites. |

Problem: New metric developed from HTS data does not correlate well with traditional environmental gradients.

- Action 1: Verify the reference database. For molecular methods, ensure the taxonomic reference database is as complete and accurate as possible. However, note that for diatoms, gaps in the barcode database have been shown to be less impactful than the fundamental differences in data structure between methods [32].

- Action 2: Re-examine the variable selection. The environmental variables driving assemblage patterns in HTS data might be different or more nuanced than those for traditional data. Explore a broader set of potential environmental predictors.

- Action 3: Validate the metric. Use a separate, independent dataset to test the metric's performance, ensuring it is not over-fitted to the original calibration data.

Research Reagent Solutions for Molecular Assemblage Analysis

For researchers employing DNA metabarcoding in their assemblage studies, the following key reagents are essential.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for DNA Metabarcoding Workflow

| Reagent / Kit | Function in the Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kit | Isolates total genomic DNA from environmental samples (e.g., water, sediment, biofilm). Critical for yield and purity. |

| PCR Primers | Targets and amplifies a specific, standardized gene region (e.g., rbcL for diatoms) for sequencing. |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Performs PCR amplification with minimal errors, ensuring accurate sequence data. |

| Size-Selective Beads | Purifies and selects appropriately sized DNA fragments for library construction, removing primer dimers and large contaminants. |

| DNA Library Preparation Kit | Prepares the amplified DNA for sequencing by adding platform-specific adapters and indexes. |

| Reference Database | Not a physical reagent, but a crucial resource for assigning taxonomy to the sequenced DNA reads [32]. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This section addresses common issues researchers encounter when applying multivariate methods in ecological indicator development.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My NMDS analysis has a high stress value. What does this mean and how can I improve it?

A high stress value (typically above 0.20) indicates poor agreement between the ordination distances and the original dissimilarity matrix [36]. To improve your NMDS results:

- Increase dimensionality: Run the analysis in 3 or more dimensions if a 2-dimensional solution has high stress [36].

- Use multiple random starts: Execute the analysis with at least 100 random starting configurations to avoid local minima [37] [36].

- Check your distance measure: Ensure you're using an appropriate distance metric for your data (e.g., Bray-Curtis for ecological community data) [37] [38].

- Transform your data: Apply appropriate transformations (e.g., Wisconsin double standardization) to reduce the influence of dominant species [37] [38].

Q2: How do I determine the optimal number of clusters in cluster analysis?

The optimal number of clusters depends on your data and research question:

- Use a scree plot: Plot the within-cluster sum of squares against the number of clusters and look for an "elbow" point [39].

- Calculate silhouette scores: Measure how similar objects are to their own cluster compared to other clusters [40].

- Consider ecological relevance: Ensure the clusters make biological sense in your research context [38] [40].

- Try hierarchical methods first: Use dendrograms from hierarchical clustering to identify natural groupings before applying partitioning methods [38].

Q3: When should I choose PCA vs. NMDS for my ecological data?

The choice depends on your data characteristics and research goals:

- Use PCA when you assume linear relationships between variables and want to maximize variance explained by each axis [41] [42].

- Choose NMDS when you have non-linear relationships or want to use any distance measure appropriate for your data [37] [43] [41].

- NMDS is preferred for community ecology data where species responses to gradients are often non-linear [37] [41].

- PCA is more suitable for environmental data where variables have linear relationships [41].

Q4: How should I prepare ecological community data for these analyses?

Proper data preparation is crucial for meaningful results:

- Standardize your data: Convert raw counts to percentages or proportions to remove the effect of sample size [38].

- Transform appropriately: Use Wisconsin double standardization (species standardization followed by sample standardization) for community data [37].

- Handle missing values: Use imputation methods or remove cases with excessive missing data [40] [44].

- Select meaningful variables: Remove rare species that occur in only a few samples to reduce noise [38].

Comparative Analysis Tables

The following tables summarize key characteristics of the three multivariate methods for easy comparison.

Table 1: Method Overview and Applications

| Characteristic | Cluster Analysis | NMDS | PCA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Group similar observations into clusters [39] [40] | Visualize similarity/dissimilarity between samples [37] [41] | Reduce dimensionality while preserving variance [41] [42] |

| Main Applications in Ecology | Identify regions with similar environmental characteristics [39]; Classify samples into distinct categories [38] | Compare community composition across sites [37] [41]; Identify environmental gradients [37] | Identify important environmental variables [41]; Analyze morphological data [42] |

| Nature of Method | Unsupervised learning [40] | Ordination technique [37] [41] | Eigenanalysis technique [41] [36] |

| Key Output | Clusters or groups [39] [40] | Ordination plot [37] [41] | Principal components [41] |

Table 2: Technical Specifications and Requirements

| Specification | Cluster Analysis | NMDS | PCA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Requirements | Requires complete data (handle missing values first) [44] | Can tolerate some missing pairwise distances [43] | Requires complete data matrix [41] |

| Distance Measures | Euclidean, Bray-Curtis, Jaccard [38] | Any measure (Bray-Curtis recommended for ecology) [37] [43] | Euclidean distance only [37] [41] |

| Assumptions | Minimal assumptions [40] | No assumption of linear relationships [37] [41] | Linear relationships between variables [41] |

| Computational Speed | Fast to moderate (depends on algorithm) [40] | Slow, particularly for large datasets [43] | Fast, efficient [41] |

Table 3: Result Interpretation and Validation

| Aspect | Cluster Analysis | NMDS | PCA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Goodness-of-fit Measures | Silhouette score [40]; Within-cluster sum of squares [44] | Stress value (Kruskal's Stress Formula) [37] [43] [36] | Percentage of variance explained [41] |

| Visualization Methods | Dendrograms (hierarchical) [38]; Scatterplots [44] | Ordination plots [37] [41]; Shepard diagrams [36] | Biplots [41]; Scree plots [36] |

| Acceptable Fit Values | Silhouette score > 0.5 (good) [40] | Stress < 0.20 (acceptable) [36] | Cumulative variance > 70% (good) |

| Validation Approaches | Stability checks with different samples [40]; Domain knowledge verification [40] | Procrustes rotation to compare with other ordinations [37]; Random starts [37] | Cross-validation; Bootstrap resampling |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Performing NMDS on Ecological Community Data

This protocol describes how to perform Non-metric Multidimensional Scaling on species abundance data using the vegan package in R [37].

Materials and Reagents

- Species abundance matrix (samples × species)

- R statistical environment (version 3.6 or higher)

- vegan package installed

- Optional: Environmental variables data frame

Procedure

- Data Preparation

- Load your species abundance data into a matrix format

- Apply Wisconsin double standardization using

decostand()function [37]

Dissimilarity Matrix Calculation

NMDS Execution

- Run NMDS with multiple random starts (

trymax=100) - Use

trace=FALSEto reduce output verbosity [37]

- Run NMDS with multiple random starts (

Result Evaluation

- Check stress value using

stressplot(varespec.nmds.bray) - Values below 0.20 are generally acceptable for interpretation [36]

- Check stress value using

Visualization

- Create ordination plot:

plot(varespec.nmds.bray, type="t") - Overlay environmental variables using

envfit()if available [37]

- Create ordination plot:

Troubleshooting Tips

- If stress remains high, increase

trymaxto 200 or more - For unstable solutions, run multiple iterations with different random seeds

- Consider data transformation if certain species dominate the analysis

Protocol 2: Hierarchical Cluster Analysis of Environmental Data

This protocol outlines steps for performing hierarchical cluster analysis on environmental data to identify groups of similar sampling sites [38].

Materials and Reagents

- Environmental measurement matrix (samples × variables)

- R statistical environment

- cluster and vegan packages installed

Procedure

- Data Standardization

- Convert data to comparable scales using appropriate transformations

- For ecological data, perform percent transformation followed by percent-maximum transformation [38]

Distance Matrix Calculation

- Compute dissimilarity matrix using Bray-Curtis dissimilarity [38]

Cluster Analysis

- Perform hierarchical clustering using Ward's method [38]

Dendrogram Visualization

- Plot dendrogram to visualize cluster relationships

- Identify natural groupings by examining branch lengths [38]

Cluster Interpretation

- Examine cluster characteristics using summary statistics

- Validate clusters with ecological knowledge of the system [38]

Troubleshooting Tips

- If clusters show chaining, try different linkage methods (e.g., UPGMA)

- Ensure variables are properly scaled to prevent dominance by high-magnitude variables

- Compare cluster results with ordination methods for validation

Workflow Visualizations

NMDS Analysis Workflow

Cluster Analysis Workflow

Method Selection Guide

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Multivariate Analysis

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Purpose | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| R Statistical Environment | Open-source platform for statistical computing and graphics [37] [38] | All multivariate analyses; data manipulation and visualization |

| vegan Package | Community ecology package for ordination and diversity analysis [37] [38] | NMDS, PERMANOVA, diversity calculations; contains essential functions like metaMDS(), vegdist() |

| Bray-Curtis Dissimilarity | Distance measure robust for ecological community data [37] [38] | Quantifying compositional differences between sites; ignores joint absences |

| Wisconsin Standardization | Double standardization method for species data [37] | Reducing influence of dominant species; equalizing contributions of rare and common species |

| Silhouette Analysis | Method for evaluating cluster quality and determining optimal number of clusters [40] | Validating cluster analysis results; measuring separation between clusters |

| Environmental Vector Fitting | Method for relating environmental variables to ordination patterns [37] | Identifying environmental drivers of community composition; envfit() function in vegan |

| Procrustes Rotation | Method for comparing two ordinations [37] | Assessing congruence between different multivariate analyses; validating NMDS results |

Within the expanding field of ecological indicator research, the development of robust and reliable risk assessment frameworks is paramount for translating scientific data into actionable environmental management practices. This technical support center addresses the core calculations that underpin these frameworks: the Predicted No-Effect Concentration (PNEC) and the Risk Quotient (RQ). These values are critical for determining the potential ecological risk of chemical substances, enabling researchers and risk assessors to establish safety thresholds and evaluate the likelihood of adverse effects in the environment. The following guides and FAQs provide detailed methodologies for these essential calculations, framed within the context of modern ecological research.

Core Concepts: PNEC and Risk Quotients

What is a Predicted No-Effect Concentration (PNEC)?

A Predicted No-Effect Concentration (PNEC) is the concentration of a substance in an environmental medium (e.g., water, soil, sediment) that is believed to be protective of the ecosystem; it is the concentration below which adverse effects are not expected to occur during long-term or short-term exposure [45] [46]. It is a benchmark derived from ecotoxicity data and is fundamental to ecological risk assessment.

What is a Risk Quotient (RQ)?

A Risk Quotient (RQ) is a ratio used to characterize ecological risk by comparing a substance's predicted environmental concentration to its toxicity [47] [45]. The formula is straightforward:

RQ = PEC / PNEC

Where:

- PEC is the Predicted Environmental Concentration.

- PNEC is the Predicted No-Effect Concentration.

The RQ is then compared to a Level of Concern (LOC). If the RQ is less than the LOC, the risk is generally considered acceptable. If the RQ exceeds the LOC, it indicates a potential risk that may warrant further investigation or management action [47].

Hazard Quotient (HQ) vs. Risk Quotient (RQ)

It is crucial to distinguish between Hazard Quotients (HQs) and Risk Quotients (RQs), as they are used in different assessment contexts [47].

Table: Comparison of Hazard Quotient (HQ) and Risk Quotient (RQ)

| Item | Hazard Quotient (HQ) | Risk Quotient (RQ) |

|---|---|---|

| Assessment Target | Human health (e.g., air toxics, industrial chemicals) | Ecological risk (e.g., pesticides) |

| Type of Risk Assessment | Human health risk assessment | Ecological risk assessment |

| Equation | HQ = Exposure Concentration / Reference Concentration (RfC) | RQ = Estimated Environmental Concentration (EEC) / Ecotoxicity Endpoint |

| Risk Description | Whether HQ is >1 or <1 | Whether RQ is > Level of Concern (LOC) or < LOC |

Detailed Methodologies and Protocols

How to Derive a PNEC Using the Assessment Factor (AF) Approach

The Assessment Factor (AF) approach is a standardized method for deriving a PNEC, especially when ecotoxicity data are limited [48] [46]. The core formula is:

PNEC = Critical Toxicity Value (CTV) / Assessment Factor (AF)

The AF accounts for uncertainties in the dataset, such as intra- and inter-species variability, differences between laboratory and field conditions, and the extrapolation of short-term data to long-term effects [46]. Environment and Climate Change Canada has developed a transparent AF approach that breaks down the overall uncertainty into three specific factors [48]:

- Endpoint Standardization Factor (FES): Standardizes various ecotoxicity endpoints (which can differ in duration, severity, and degree of effect) to a long-term, sub-lethal, no- or low-effect level.

- Species Variation Factor (FSV): Addresses the uncertainty due to the number of species and organism categories (primary producers, invertebrates, vertebrates) tested.

- Mode of Action Factor (FMOA): Considers whether the substance's specific mode of toxic action is adequately reflected in the available dataset.

The overall assessment factor is the product of these three factors: AF = FES × FSV × FMOA.

Table: Endpoint Standardization Factor (FES) Criteria [48]