Democratizing Ecology: A Comprehensive Guide to Low-Cost Open-Source Technologies for Environmental Monitoring

This article explores the transformative potential of low-cost, open-source technologies in ecological and environmental monitoring.

Democratizing Ecology: A Comprehensive Guide to Low-Cost Open-Source Technologies for Environmental Monitoring

Abstract

This article explores the transformative potential of low-cost, open-source technologies in ecological and environmental monitoring. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and development professionals, it provides a foundational understanding of open-source hardware and software, showcases practical methodologies and real-world applications, addresses critical calibration and data management challenges, and offers comparative validation against proprietary systems. By synthesizing insights from current deployments and emerging research, this guide serves as a vital resource for implementing cost-effective, adaptable, and transparent monitoring solutions that can democratize data collection and inform evidence-based policy and clinical research decisions.

The Open-Source Revolution: Principles and Drivers Transforming Ecological Monitoring

Defining Open-Source Hardware and Software for Environmental Science

The growing need for scalable and affordable solutions in environmental science has catalyzed the adoption of open-source technologies. Open-source hardware (OSH) and open-source software (OSS) provide a powerful, collaborative framework for developing low-cost, adaptable, and transparent tools for ecological monitoring and research. This paradigm shift empowers researchers, scientists, and conservationists to study complex environmental systems with unprecedented detail and at a fraction of the cost of traditional proprietary systems. This guide provides a technical definition of OSH and OSS, details their application in environmental science, and presents standardized protocols for their implementation in low-cost ecological monitoring.

Core Definitions and Principles

Open-Source Hardware (OSH)

Open-source hardware (OSH) consists of physical artifacts of technology whose design is made publicly available. This allows anyone to study, modify, distribute, make, and sell the design or hardware based on that design [1] [2]. The "source" for hardware—the design files—is provided in the preferred format for making modifications, such as the native file format of a CAD program, mechanical drawings, schematics, bills of material, and PCB layout data [1] [2].

The Open Source Hardware Association (OSHWA) outlines key criteria for OSH, which include: the provision of comprehensive documentation, freedom to create derived works, free redistribution without royalties, non-discrimination against persons or fields of endeavor, and that the license must not be specific to a single product or restrict other hardware or software [2]. The principle is to maximize the ability of individuals to make and use hardware by leveraging readily-available components, standard processes, and open infrastructure [2].

Open-Source Software (OSS)

Open-source software (OSS) is software whose source code is made publicly available under a license that grants users the rights to use, study, change, and distribute the software and its source code to anyone and for any purpose [3] [4]. The core tenets, as defined by the Open Source Initiative (OSI), include free redistribution, availability of source code, permission for derived works, integrity of the author's source code, and no discrimination against persons or fields of endeavor [3] [4].

A key operational distinction from commercial software is that OSS is often developed and maintained collaboratively, with its evolution and "servicing" stages happening concurrently and transparently, frequently within public version control repositories [4]. Licenses generally fall into two main categories: copyleft licenses, which require that derivative works remain under the same license, and non-copyleft or permissive licenses, which allow integration with proprietary software [4].

Table 1: Core Principles of Open-Source Hardware and Software

| Principle | Open-Source Hardware (OSH) | Open-Source Software (OSS) |

|---|---|---|

| Availability | Design files (schematics, CAD) are publicly available [2]. | Human-readable source code is publicly available [4]. |

| Freedom to Use | Can be used for any purpose without discrimination [2]. | Can be used for any purpose without discrimination [3]. |

| Freedom to Modify | Design files can be modified; derived works are allowed [2]. | Source code can be modified; derived works are allowed [3]. |

| Freedom to Distribute | Design files and hardware based on them can be freely distributed and sold [1]. | Source code and software can be freely redistributed and sold [3]. |

| License Types | Licenses like CERN OHL, TAPR OHL [1]. | Copyleft (e.g., GPL) and non-copyleft (e.g., MIT, Apache) [4]. |

The Role of Open-Source in Environmental Science

The application of OSH and OSS is transforming environmental science by enabling the development of low-cost, highly customizable research tools that are particularly suited for extensive ecological monitoring.

Open-Source Hardware Applications

OSH finds diverse applications in environmental science, spanning electronics, sensors, and complete monitoring systems. For example, the PICT (Plant-Insect Interactions Camera Trap) is an open-source hardware and software solution based on a Raspberry Pi Zero, designed as a modular, low-cost system for studying close-range ecological interactions [5]. Other prominent examples include 3D printers like RepRap and Prusa, which are themselves open-source and can be used to fabricate custom components for scientific equipment, and open-source water quality sensors and weather stations [1]. These tools allow researchers to deploy larger sensor networks, increasing spatial and temporal data resolution while minimizing costs.

Open-Source Software Applications

OSS provides the analytical backbone for modern environmental science. A suite of open-source software exists specifically for managing and analyzing ecological data. For camera trap studies, tools like TRAPPER (a collaborative web platform), camtrapR (an R package for advanced statistical analysis like occupancy modeling), and EcoSecrets (a web platform for centralized media management) enable efficient data processing from raw images to statistical results [5].

Beyond domain-specific software, general-purpose quantitative analysis tools like R and RStudio are pivotal. R is a fully open-source environment for statistical computing and graphics, supported by thousands of packages for advanced analysis, modeling, and data visualization, making it a cornerstone for ecological data analysis [6]. Similarly, Apache Superset is an open-source business intelligence tool that can connect directly to data warehouses to create interactive dashboards and visualizations for environmental data reporting [7].

Table 2: Representative Open-Source Tools for Ecological Monitoring

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Application in Environmental Science | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| PICT [5] | Hardware & Software | Close-range ecological interaction monitoring | Modular, low-cost Raspberry Pi-based system |

| camtrapR [5] | Software (R package) | Camera trap data analysis and occupancy modeling | Integration with advanced statistical models in R |

| EcoSecrets [5] | Software (Web Platform) | Centralized management of ecological media and data | Standardized annotation and interoperability with GIS |

| R / RStudio [6] | Software (Statistical Computing) | General-purpose statistical analysis and data visualization | Extensive CRAN package library for diverse analyses |

| Apache Superset [7] | Software (Business Intelligence) | Interactive dashboarding and data exploration | Warehouse-native; connects directly to data sources |

| Open Source Ecology [1] | Hardware | Ecosystem of open-source mechanical tools for resilience | Enables local fabrication of necessary machinery |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Implementing open-source technologies requires structured workflows. Below is a generalized protocol for deploying an open-source camera trap system, from hardware setup to data analysis.

Protocol: Deployment of an Open-Source Camera Trap System

Objective: To monitor wildlife presence and abundance using a low-cost, open-source camera trap system and analyze the data using open-source software pipelines.

Materials and Reagents:

- Camera Trap Hardware: Commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) units or a custom OSH design like PICT [5].

- Storage Media: High-capacity SD cards.

- Power Source: Lithium batteries or solar power kits.

- Data Processing Server/Computer: A computer with sufficient storage and processing power.

- Software: TRAPPER, Camelot, or EcoSecrets for data management; camtrapR or R for statistical analysis [5].

Methodology:

- Hardware Deployment:

- Securely mount camera traps at pre-determined GPS locations, following standardized protocols for height, angle, and placement to avoid false triggers.

- Install batteries and SD cards. Configure camera settings (e.g., sensitivity, image resolution, delay between triggers).

- Record deployment metadata: deployment ID, coordinates, date, time, camera orientation, and habitat description.

Data Collection and Ingestion:

- Regularly retrieve SD cards and replace them with formatted ones.

- Upload image sets to the designated open-source data management platform (e.g., TRAPPER, EcoSecrets). The platform should automatically associate images with their deployment metadata [5].

Image Annotation and Processing:

- Manual Annotation: Within the platform, users can visually identify species, count individuals, and record behaviors in each image.

- AI-Assisted Annotation: For large datasets, use integrated AI tools like MegaDetector (an AI model for detecting animals in images) to filter out empty images and pre-classify species, which is then verified by human annotators [5].

Data Analysis:

- Export the standardized and annotated data from the management platform.

- Import the data into camtrapR in R for statistical analysis [5].

- Perform analyses such as:

- Species Richness Estimation: Calculate the number of different species detected.

- Occupancy Modeling: Estimate the probability of a species occupying a site while accounting for imperfect detection [5].

- Relative Abundance Index: Calculate the number of detections per unit effort.

- Activity Pattern Analysis: Model the daily activity patterns of different species.

Data Visualization and Reporting:

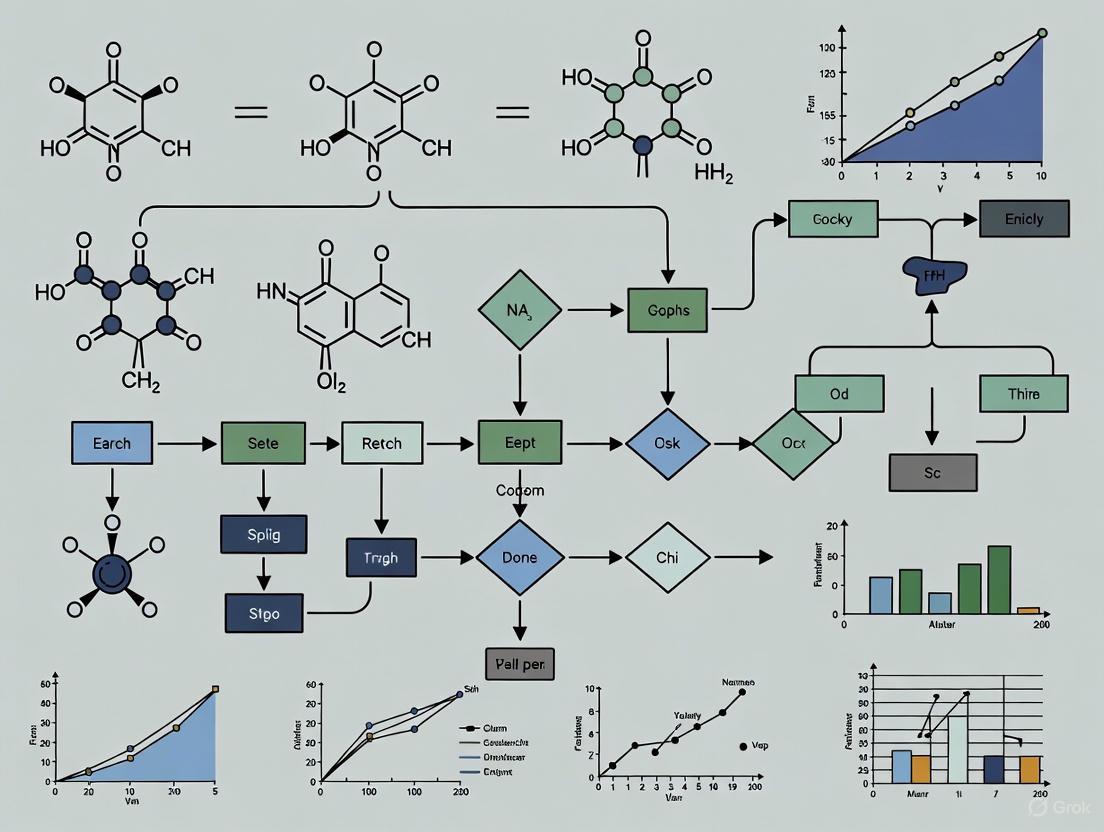

Diagram 1: OSH/OSS Workflow for Ecological Monitoring.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Open-Source Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Open-Source Environmental Monitoring

| Item / Solution | Type | Function in Research Context |

|---|---|---|

| Raspberry Pi/Arduino [1] | Hardware | Serves as the programmable, low-cost computational core for custom sensor systems and monitoring devices. |

| R & RStudio [6] [5] | Software | Provides a comprehensive, open-source environment for statistical analysis, modeling, and generating reproducible scripts for ecological data. |

| MegaDetector [5] | Software (AI Model) | Automates the initial filtering of camera trap images by detecting and bounding animals, people, and vehicles, drastically reducing manual review time. |

| camtrapR R package [5] | Software | Provides specialized functions for organizing camera trap data and conducting advanced statistical analyses like occupancy and abundance modeling. |

| TRAPPER / EcoSecrets [5] | Software (Platform) | Acts as a centralized, collaborative database for managing project metadata, media files, and annotations, ensuring data integrity and standardization. |

| 3D Printer (e.g., RepRap) [1] | Hardware | Enables on-demand fabrication of custom equipment housings, sensor mounts, and other mechanical components, accelerating prototyping and deployment. |

| Apache Superset [7] | Software | Enables the creation of interactive dashboards and visualizations for real-time or historical reporting of environmental metrics to diverse audiences. |

Open-source hardware and software represent a foundational shift in the methodology of environmental science. By providing transparent, adaptable, and low-cost alternatives to proprietary systems, they democratize access to advanced monitoring and analytical capabilities. The formal definitions and structured protocols outlined in this guide provide a framework for researchers to implement these technologies effectively. The integration of OSHW for data acquisition and OSS for data management and analysis creates a powerful, end-to-end open-source pipeline. This approach not only reduces financial barriers but also enhances scientific reproducibility, collaboration, and the pace of innovation in addressing pressing ecological challenges.

The field of ecological monitoring is undergoing a transformative shift, driven by the convergence of low-cost open-source technologies and the burgeoning Right to Repair movement. This synergy addresses a critical challenge in environmental science: the need for scalable, sustainable, and democratized research tools. Traditional proprietary research equipment often suffers from high costs, limited reparability, and manufacturer-imposed repair restrictions, creating significant barriers to long-term, large-scale ecological studies [8] [9]. The "throwaway mentality" associated with such equipment is not only economically wasteful but also environmentally unsustainable, given the precious metals and resources embedded in electronic devices [8].

This whitepaper articulates a framework where the core principles of accessibility, reproducibility, and the Right to Repair are foundational to advancing ecological research. We argue that integrating these principles into the design and deployment of research tools is essential for building resilient, transparent, and collaborative scientific practices. By embracing open-source designs and championing repair rights, researchers can develop monitoring infrastructures that are not only scientifically robust but also economically and environmentally sustainable [10] [5]. This approach empowers scientists to maintain control over their instrumentation, ensures the longevity of research projects, and reduces electronic waste, aligning scientific progress with the urgent goals of a circular economy [11] [12].

Defining the Core Principles

Accessibility

In the context of ecological monitoring technology, accessibility encompasses three key dimensions: economic, technical, and informational. Economic accessibility refers to the development and use of low-cost tools that minimize financial barriers for researchers, NGOs, and citizen scientists globally [10]. Technical accessibility entails designing hardware and software that can be easily fabricated, modified, and operated by end-users without specialized expertise, often through open-source platforms like Arduino or Raspberry Pi [10] [5]. Informational accessibility requires that all design files, source code, and documentation are publicly available under permissive licenses, enabling anyone to study, use, and improve upon existing tools. This comprehensive approach to accessibility ensures that the capacity to monitor and understand ecosystems is not limited by resource constraints or proprietary barriers.

Reproducibility

Scientific reproducibility ensures that research findings can be independently verified and built upon, a cornerstone of the scientific method. For ecological monitoring, this extends beyond methodological transparency to include technical reproducibility—the ability for other researchers to replicate the data collection system itself. Open-source technologies are critical for this principle, as they provide complete visibility into the hardware and software stack used for data acquisition [10] [5]. When a research team publishes its findings, providing access to the exact sensor designs, data logger code, and analysis algorithms allows others to confirm results and adapt the tools for new studies. This creates a virtuous cycle where research infrastructure becomes more robust and validated through widespread use and replication across different environmental contexts.

Right to Repair

The Right to Repair is a legal and design principle that guarantees end-users the ability to maintain, modify, and repair the products they own. For ecological researchers, this translates to unrestricted access to repair manuals, diagnostic tools, firmware, and affordable replacement parts for their field equipment [8] [13]. The movement directly challenges manufacturer practices that inhibit repair, such as parts pairing (using software locks to prevent the installation of unauthorized components) and restricted access to service information [8] [13]. In remote field research stations or underfunded conservation projects, the inability to repair a critical sensor can mean the loss of invaluable longitudinal data. Embedding the Right to Repair into scientific tools is therefore not merely a matter of convenience but a prerequisite for reliable, long-term environmental observation and data integrity.

The Legal and Policy Landscape for Repairable Research

The global legislative momentum behind the Right to Repair is creating a more favorable environment for open-source scientific tools. Understanding this landscape is crucial for researchers navigating equipment procurement and development.

Table 1: Key Right to Repair Legislation and Implications for Scientific Research

| Jurisdiction/Law | Key Provisions | Relevance to Research Equipment |

|---|---|---|

| European Union Right to Repair Directive [8] [11] | Mandates provision of product documentation, parts, and tools to consumers and independent repairers (effective July 2026). | Ensures access to repair resources for EU-purchased equipment, supporting long-term ecological studies. |

| California SB 244 [12] | Requires manufacturers to provide parts, tools, and documentation for 3-7 years after product manufacture, depending on cost. | Protects investments in costly research equipment by guaranteeing repair access for a defined period. |

| Oregon's Law (2024) [8] [13] | Bans "parts pairing," preventing software locks that disable functionality with third-party parts. | Critical for sensor and device interoperability, allowing researchers to modify and repair with generic components. |

| New York Digital Fair Repair Act [12] | Grants independent repair providers access to diagnostic tools, manuals, and parts on fair terms. | Fosters a competitive repair market for lab and field equipment, reducing costs and downtime. |

The legal distinction between permissible repair and impermissible reconstruction is pivotal. Courts often consider factors such as the extent and nature of parts replaced, and whether the activity restores the existing item or effectively creates a new one [11]. For researchers, replacing a worn sensor or a broken data logger case typically constitutes permissible repair. However, systematically replacing all major components of a device could be deemed reconstruction, potentially infringing on patents [11]. This legal framework underscores the importance of designing modular research tools where individual components can be legally and easily replaced without contest.

Implementing Principles in Ecological Monitoring: A Technical Guide

The Open-Source Research Toolkit

Adhering to the core principles requires a curated suite of tools and practices. The following table details essential "research reagent solutions" for building and maintaining accessible, reproducible, and repairable monitoring systems.

Table 2: Essential Open-Source Tools and Practices for Ecological Monitoring

| Tool / Practice | Function | Principle Demonstrated |

|---|---|---|

| Open-Source Microcontrollers (e.g., Arduino MKR) [10] | Serves as the core controller for custom-built environmental sensors (e.g., data loggers). | Accessibility & Reproducibility: Low-cost, widely available, and supported by extensive open-source code libraries. |

| Low-Power Wide-Area Networks (e.g., LoRaWAN) [10] | Enables long-range, low-power wireless data transmission from remote field sites. | Accessibility: Reduces the cost and complexity of data retrieval from inaccessible areas. |

| Open-Source Camera Trap Software (e.g., TRAPPER, Camelot) [5] | Manages the annotation, storage, and analysis of large volumes of camera trap imagery. | Reproducibility & Accessibility: Provides standardized, collaborative workflows for handling ecological data. |

| Repair Cafes & Community Support [8] | Community-led spaces where people share repair knowledge and tools. | Right to Repair: Offers a grassroots support network for maintaining and fixing research equipment. |

| Public Repositories (e.g., GitHub, OSF) | Hosts and versions design files, code, and documentation for research projects. | Reproducibility & Accessibility: Ensures all aspects of a research tool are transparent and available for replication. |

Experimental Protocol: Deploying an Open-Source Environmental Data Logger

The following workflow, represented in the diagram below, outlines the methodology for deploying a repairable, open-source data logger for long-term river monitoring, based on systems like the eLogUp [10]. This protocol emphasizes the integration of our core principles at every stage.

Workflow Title: Open-Source Ecological Data Logger Lifecycle

Detailed Methodology:

Hardware Fabrication and Calibration: Select an open-source hardware platform such as an Arduino MKR board for its low-power operation and connectivity options [10]. Interface it with commercially available sensors for parameters like temperature, turbidity, or dissolved oxygen. All components should be solderable and use standard connectors. Calibrate sensors using reference standards before deployment, and document the entire calibration procedure publicly.

Firmware Development and Data Logging: Develop data acquisition firmware in a open-source environment (e.g., Arduino IDE or PlatformIO). The code should implement power-saving modes (e.g., periodic wake-up) to enable long-term operation on battery or solar power. The firmware and all dependencies must be version-controlled and published on a public repository like GitHub to ensure full reproducibility [10].

Field Deployment and Data Management: Deploy the housed unit in the target environment (e.g., riverbank). Utilize a low-power, long-range communication protocol like LoRaWAN to transmit data to a central server [10]. This eliminates the need for physical access to the device for data retrieval, enhancing data continuity. Incoming data should be automatically timestamped and stored in an open, non-proprietary format (e.g., CSV, JSON).

Scheduled Maintenance and Repair: Establish a maintenance schedule based on sensor drift and battery life estimates. The Right to Repair is operationalized here: when a component fails (e.g., a sensor probe), the open-source documentation allows any technician to identify the part. Standard, non-paired components can be sourced and replaced on-site without requiring manufacturer intervention [8] [13]. This process should be meticulously logged.

Data Analysis and Publication: Analyze the collected time-series data using open-source tools (e.g., R, Python). Crucially, for the research to be reproducible, the final published work must link to the specific hardware design, firmware version, raw data, and analysis scripts used [10] [5].

The integration of accessibility, reproducibility, and the Right to Repair is not a peripheral concern but a central strategy for resilient and ethical ecological research. By championing low-cost, open-source technologies and fighting for the right to maintain our scientific tools, we build a research infrastructure that is more democratic, transparent, and capable of addressing the long-term challenges of environmental monitoring. This approach directly counters the unsustainable cycle of planned obsolescence and e-waste, aligning the scientific community with the broader goals of a circular economy [8] [12].

The trajectory is clear: legislative and cultural shifts are increasingly favoring repair and open access. For researchers, scientists, and developers, the imperative is to proactively embed these core principles into their work—from the design of a single sensor to the architecture of large-scale monitoring networks. The future of ecological understanding depends on our ability to observe the natural world consistently and collaboratively. By building tools that everyone can use, fix, and trust, we lay the foundation for a more sustainable and knowledgeable future.

Addressing Global Inequalities and Prohibitive Costs of Proprietary Systems

The field of ecological monitoring faces a critical challenge: the urgent need to understand and protect global biodiversity is hampered by technological inequalities and the prohibitive costs of proprietary systems. This disparity creates significant barriers for researchers in the Global South and those with limited funding, effectively creating epistemic injustice where research questions are constrained by the physical tools researchers can access [14]. Proprietary monitoring equipment often carries steep licensing fees, vendor lock-in, and legal restrictions that prevent maintenance and modification [14]. In response to these challenges, open-source hardware—defined as hardware whose design is "made publicly available so that anyone can study, modify, distribute, make, and sell the design or hardware based on that design"—emerges as a transformative solution [14].

The open-source model aligns with the UNESCO Recommendation on Open Science, promoting inclusive, equitable, and sustainable approaches to scientific practice [14]. Evidence indicates that open-source hardware can generate cost savings of up to 87% compared to proprietary functional equivalents while maintaining scientific rigor [14]. For instance, the SnapperGPS wildlife tracker provides comparable functionality to proprietary units costing thousands of dollars for a component cost of under $30 [14]. This dramatic cost reduction, coupled with the freedoms to adapt and repair equipment, positions open-source technologies as powerful tools for democratizing ecological research and monitoring capabilities worldwide.

Quantitative Comparison: Open-Source vs. Proprietary Solutions

The following tables summarize empirical data comparing the performance and cost characteristics of open-source and proprietary ecological monitoring technologies, based on published studies and implementations.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Open-Source and Proprietary Monitoring Devices

| Device / System | Parameter Measured | Accuracy (Open-Source) | Accuracy (Proprietary) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DIY Soil Temperature Logger | Soil Temperature (-20–0 °C) | 98% | N/A (Reference) | [15] |

| DIY Soil Temperature Logger | Soil Temperature (0–20 °C) | 99% | N/A (Reference) | [15] |

| Automated Seabird Monitoring | Bird Counting | 98% (vs. manual count) | N/A (Manual Reference) | [16] |

| Automated Seabird Monitoring | Species Identification | >90% | N/A (Manual Reference) | [16] |

| CoSense Unit (Air Quality) | Various pollutants | Consistent & reliable (Co-located validation) | Equivalent to government station | [17] |

Table 2: Cost-Benefit Analysis of Open-Source vs. Proprietary Monitoring Solutions

| System Type | Example | Cost Factor | Commercial Equivalent Cost | Savings/Advantage | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental Sensor Network | FORTE Platform | Cost-effective deployment | High (Commercial solutions) | Scalable, energy-efficient, reliable data quality | [18] |

| Wildlife Tracker | SnapperGPS | <$30 component cost | Thousands of USD | ~87% cost reduction | [14] |

| Data Logger | DIY Soil Temperature Logger | 1.7-7x less expensive | Commercial systems (e.g., Onset HOBO) | Substantial economy of scale | [15] |

| Coastal Monitoring | Marajo Island System | 5-25x cheaper | Equivalent commercial solutions | Open-source hardware, 3D printing, local assembly | [19] |

| Lab Equipment | OpenFlexure Microscope | Significant cost reduction | Commercial lab-grade microscopes | Adaptable to field use as dissection microscope | [14] |

Open-Source Frameworks for Environmental Monitoring

The FORTE Platform for Forest Monitoring

The FORTE (Open-Source System for Cost-Effective and Scalable Environmental Monitoring) platform represents a comprehensive approach to forest ecosystem monitoring. This system architecture includes two primary components: (1) a wireless sensor network (WSN) deployed throughout the forest environment for distributed data collection, and (2) a centralized Data Infrastructure for processing, storage, and visualization [18]. The WSN features a Central Unit capable of transmitting data via LTE-M connectivity, coupled with multiple spatially independent Satellites that collect environmental parameters across large areas, transmitting data wirelessly to the Central Unit [18]. Field tests demonstrate that FORTE achieves cost-effectiveness compared to commercial alternatives, high energy efficiency with sensor nodes operating for several months on a single charge, and reliable data quality suitable for research applications [18].

Soc-IoT: A Citizen-Centric Framework

The Social, Open-Source, and Citizen-Centric IoT (Soc-IoT) framework addresses the critical need for community-engaged environmental monitoring. This integrated system comprises two synergistic components: the CoSense Unit and the exploreR application [17]. The CoSense Unit is a resource-efficient, portable, and modular device validated for both indoor and outdoor environmental monitoring, specifically designed to overcome accuracy limitations common in low-cost sensors through rigorous co-location testing with reference instruments [17]. Complementing the hardware, exploreR is an intuitive, cross-platform data analysis and visualization application built on RShiny that provides comprehensive analytical tools without requiring programming knowledge, effectively democratizing data interpretation [17]. This framework explicitly addresses technological barriers while promoting environmental resilience through open innovation.

AI-Enhanced Biodiversity Monitoring Systems

Cutting-edge approaches now integrate artificial intelligence with open-source principles to revolutionize biodiversity assessment. These systems employ Bayesian adaptive design methodologies to optimize data collection efficiency, strategically deploying resources to the most informative spatial and temporal contexts rather than continuously recording data [20]. The integration of 3D-printed high-resolution audio recording devices with novel wireless transmission technology eliminates the logistical burdens typically associated with field data retrieval [20]. For data interpretation, Joint Species Distribution Models based on interpretable AI, such as Bayesian Pyramids, enable researchers to characterize ecological communities and estimate species abundances from acoustic data while maintaining analytical transparency [20].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

DIY Soil Temperature Logger Construction and Validation

The open-source soil temperature data logger based on the Arduino platform provides a robust methodology for high-density spatial monitoring of soil thermal regimes [15]. The construction and validation protocol follows these key stages:

Part Procurement and Assembly: The system utilizes a custom printed circuit board controlled by an embedded microcontroller (ATMEGA328P) running open-source Arduino software. The board incorporates a battery-backed real-time clock (DS1307N+), level-shifting circuitry for removable SD card storage, and ports for up to 11 digital temperature sensors (DS18B20) [15]. Assembly is performed using commonly available tools (soldering irons, pliers) following detailed online video tutorials and written instructions.

Programming and Testing: Devices are programmed using open-source code repositories, with interactive software routines to register external temperature sensors and conduct self-testing procedures. Following successful testing, units are waterproofed using inexpensive PVC pipe enclosures with cable glands for sensor passthrough [15].

Validation Methodology: Performance validation employs laboratory cross-referencing against commercial systems (Onset HOBO Pro v2) across a temperature gradient from -20°C to 70°C using water baths and controlled environments. Field validation involves long-term deployment in extreme environments (Arctic Alaska) with annual data retrieval but no preventive maintenance, demonstrating reliability under challenging conditions [15].

Automated Seabird Monitoring System

The AI-driven seabird monitoring system exemplifies the integration of computer vision with ecological principles for automated population assessment [16]:

Image Acquisition: The system utilizes remote-controlled cameras deployed in mixed breeding colonies to capture visual data of breeding seabirds, focusing on visually similar species (Common Tern and Little Tern) [16].

Object Detection and Classification: The YOLOv8 deep learning algorithm performs initial object detection, with subsequent classification enhancement through integration of ecological and behavioral features including spatial fidelity, movement patterns, and size differentials obtained via camera calibration techniques [16].

Validation and Mapping: System accuracy is quantified through comparison with manual counts, achieving 98% agreement, while species identification accuracy exceeds 90%. The system generates high-resolution spatial mapping of nesting individuals, providing insights into habitat use and intra-colony dynamics [16].

Low-Cost Sensor Validation Protocol

The critical issue of data quality in low-cost environmental sensors is addressed through rigorous validation protocols [17]:

Co-location Testing: Open-source sensor units (e.g., CoSense Unit) are deployed alongside government-grade reference monitoring stations for extended periods to collect parallel measurements [17].

Calibration Procedures: Development of openly published calibration methodologies that identify and correct for systematic errors in sensor response, including the identification of calibration drift in proprietary systems that may go undetected [14].

Data Quality Assessment: Comprehensive evaluation of sensor accuracy, precision, and long-term stability under real-world conditions, with particular attention to environmental factors such as temperature and humidity dependencies [17].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Open-Source Solutions

Table 3: Open-Source Research Reagent Solutions for Ecological Monitoring

| Tool / Component | Function | Key Features | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arduino Microcontroller | Data logger control | Open-source hardware/software, extensive community support, modular sensors | DIY Soil Temperature Logger [15] |

| SnapperGPS | Wildlife location tracking | Ultra-low cost (<$30), community support forum, open design | Wildlife tracking for budget-limited projects [14] |

| OpenFlexure Microscope | Laboratory and field microscopy | Lab-grade optics, adaptable design, field-convertible to dissection scope | Orchid bee identification in Panama [14] |

| OpenCTD | Oceanographic measurements | Coastal monitoring, openly published calibration procedures | Identification of calibration errors in proprietary systems [14] |

| CoSense Unit | Environmental sensing | Modular air quality monitoring, validated against reference stations | Citizen science air quality projects [17] |

| exploreR Application | Data analysis and visualization | No-code analytical platform, RShiny-based, intuitive interface | Democratizing data interpretation [17] |

| Bayesian Pyramids (AI) | Species distribution modeling | Interpretable neural networks, constrained parameters with real data | Ecological community characterization [20] |

The adoption of open-source technologies for ecological monitoring represents both an immediate solution to cost and accessibility challenges and a long-term strategy for building equitable, sustainable research capacity globally. Successful implementation requires:

Adherence to Open-Source Publication Standards: Following established frameworks such as the Open Know-How specification, which defines structured metadata including bills of materials and design files, typically published via platforms like GitHub or GitLab with appropriate open-source licenses [14].

Institutional Policy Reform: Research institutions and funding agencies should recognize open-source hardware development as a valuable scholarly contribution, create corresponding career pathways, and embed open-source principles in training programs [14].

Hybrid Innovation Models: Embracing commercially friendly open-source approaches that enable sustainable business models while preserving the core freedoms to study, modify, and distribute technologies [14].

The integration of open-source hardware with advanced AI analytics, as demonstrated in automated biodiversity monitoring systems, creates powerful synergies that can revolutionize ecological research while addressing historical inequalities in research capacity [20]. By democratizing access to monitoring technologies, the global research community can accelerate our understanding of pressing ecological challenges from climate change to biodiversity loss, enabling more effective conservation interventions grounded in comprehensive, fine-grained environmental data.

The Role of Open-Source in Democratizing Data for Vulnerable Communities

The democratization of environmental data represents a fundamental shift in the power dynamics of information, placing the capacity to monitor, understand, and advocate for local ecosystems directly into the hands of vulnerable communities. This transformation is critically enabled by the convergence of low-cost open-source technologies and innovative methodologies that make sophisticated ecological monitoring accessible outside traditional research institutions [21]. For researchers and scientists working with these communities, understanding this technological landscape is no longer optional but essential for conducting relevant, impactful, and equitable research.

The core challenge this paper addresses is the historical concentration of environmental monitoring capabilities within well-funded institutions, which has often left the communities most affected by environmental degradation without the data to prove it or advocate for change [21]. Open-source technologies—spanning hardware, software, and data protocols—are dismantling these barriers. They enable the collection of research-grade data at a fraction of the cost, fostering a new paradigm of community-led science and data sovereignty. This guide provides a technical foundation for researchers seeking to implement these solutions, detailing the components, validation methods, and integrative frameworks that make robust, community-based ecological monitoring a practicable reality.

The Open-Source Technological Ecosystem

The ecosystem of open-source tools for ecological monitoring is diverse, encompassing physical data loggers, sophisticated AI models, and community-driven data platforms. Together, they form a stack that allows for end-to-end data collection, analysis, and utilization.

Hardware: Low-Cost Data Acquisition Systems

At the hardware level, open-source environmental monitoring systems have demonstrated performance comparable to commercial counterparts while dramatically reducing costs. These systems typically consist of modular, customizable data loggers and sensors.

A critical study comparing open-source data loggers to commercial systems found a strong correlation (R² = 0.97) for temperature and humidity measurements, validating their suitability for research [22]. The primary advantage lies in cost-effectiveness; these systems can be deployed at 13-80% of the cost of comparable commercial systems, enabling much higher sensor density for capturing fine-scale ecological gradients [22].

Table 1: Performance and Cost Analysis of Open-Source vs. Commercial Monitoring Systems

| Metric | Open-Source Systems | Commercial Systems | Implication for Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Accuracy (e.g., Temp/RH) | High (R² = 0.97 vs. reference) [22] | High | Research-grade data attainable at lower cost. |

| Relative Cost | 13-80% of commercial cost [22] | Baseline (100%) | Enables high-density sensor networks and scalable deployment. |

| Customization & Flexibility | High (modular, adaptable sensors) [23] | Low to Moderate (often proprietary) | Can be tailored to specific ecological variables and community needs. |

| Key Applications | Forest fire ecology, urban forestry, microclimate characterization [22] | Broad ecological studies | Effective for fine-scale, mechanistic ecological studies. |

These systems are being applied in diverse ecological contexts, from examining micrometeorology in fire-prone ecosystems to studying microsite variability in dry conifer systems and climate mediation effects in urban forests [22]. The PROMET&O system, for instance, is an open-source solution for indoor environmental quality monitoring that emphasizes flexibility in hardware design and optimizes sensor placement to minimize cross-sensitivity [23]. Its data preprocessing extracts significant statistical parameters, reducing the amount of data transferred—a crucial feature for deployments in areas with limited connectivity [23].

Software & AI: Analytical and Identification Tools

On the software side, open-source platforms are making advanced artificial intelligence accessible for species identification and data analysis. A leading example is Pytorch-Wildlife, an open-source deep learning framework built specifically for conservation tasks [24].

- Accessibility: Designed for users with limited technical backgrounds, it can be installed via

pipand includes an intuitive user interface. It is also hosted on Hugging Face for remote use, eliminating hardware barriers [24]. - Modular Codebase: The framework is built for scalability, allowing researchers to easily integrate new models, datasets, and features tailored to their specific monitoring context [24].

- Model Zoo: It provides a collection of pre-trained models for animal detection and classification. For example, its model for the Amazon Rainforest achieves 92% recognition accuracy for 36 animal genera in 90% of the data, demonstrating high efficacy [24].

This framework lowers the barrier to using powerful AI tools, enabling local researchers and communities to process large volumes of camera trap or acoustic data without relying on proprietary software or external experts.

Data: Community Networks and Open Platforms

Beyond hardware and software, the open-source ethos is embodied by global communities and platforms that promote data sharing and collaborative development. Sensor.Community is a prime example of a contributor-driven global sensor network that creates open environmental data [25]. Such initiatives operationalize the principle of democratization by building a commons of environmental information that is freely accessible and contributed to by a distributed network of individuals and groups.

Technical Implementation and Experimental Protocols

Implementing a successful open-source monitoring project requires careful planning from sensor deployment to data interpretation. This section outlines a generalized workflow and a specific protocol for sensor-based microclimate studies.

End-to-End Workflow for Community Monitoring

The following diagram visualizes the integrated workflow of a community-driven environmental monitoring project, from sensor setup to data-driven action.

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Microclimate Assessment

This protocol is adapted from research validating low-cost sensors for forest ecology applications [22].

1. Research Question and Hypothesis Formulation:

- Question: How do microclimatic variables (e.g., temperature, humidity) vary at a fine spatial scale within a defined vulnerable ecosystem (e.g., a community forest facing drought or a urban heat island)?

- Hypothesis: Significant microclimate gradients exist at scales of <100 meters, correlated with topographical features or land cover.

2. Sensor Selection and Kit Assembly (The Researcher's Toolkit):

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Open-Source Microclimate Monitoring

| Item | Specification/Example | Primary Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Open-Source Datalogger | e.g., Arduino-based, Raspberry Pi | The central processing unit that records and time-stamps measurements from all connected sensors. |

| Temperature/Humidity Sensor | e.g., DHT22, SHT31 | Measures ambient air temperature and relative humidity, key for understanding thermal stress and evapotranspiration. |

| Soil Moisture Sensor | e.g., Capacitive sensor (not resistive) | Measures volumetric water content in soil, critical for studying drought impacts and water availability for vegetation. |

| Solar Radiation/ PAR Sensor | e.g., Silicon photodiode sensor | Measures photosynthetically active radiation (PAR), essential for understanding light availability for plant growth. |

| Weatherproof Enclosure | IP65 or higher rated box | Protects the electronic components from rain, dust, and other environmental damage. |

| Power Supply | Solar panel + battery pack | Provides autonomous power for long-term deployment in remote locations without grid access. |

| Data Storage/ Transmission | SD card module or LoRaWAN/GSM module | Enables local data storage or wireless transmission of collected data to a cloud server or local base station. |

3. Pre-Deployment Calibration and Validation:

- Co-location Calibration: Place all low-cost sensors next to a research-grade reference instrument in a controlled or representative environment for a minimum period (e.g., 1-2 weeks).

- Regression Analysis: Plot the readings from the low-cost sensors against the reference data to generate a calibration curve (e.g., slope, intercept, R²). Apply this correction factor to all subsequent field data [22] [23].

- Sensor Shielding: Construct radiation shields for temperature sensors to prevent direct solar heating from causing inaccurate readings.

4. Field Deployment and Data Collection:

- Site Selection: Choose locations strategically to test the hypothesis (e.g., north vs. south slope, canopy vs. clearing, urban vs. vegetated area).

- Installation: Secure sensors at standardized heights (e.g., 1.5m for air temperature) and depths (for soil sensors). Ensure the power supply is stable.

- Data Acquisition: Program the datalogger to record measurements at a time interval appropriate for the phenomenon (e.g., every 5-15 minutes). For the PROMET&O system, strategies are employed to reduce data transfer rates without information loss, which is a key consideration in low-bandwidth areas [23].

5. Data Processing, Analysis, and Interpretation:

- Data Cleaning: Apply calibration equations. Filter out obvious outliers caused by sensor errors.

- Statistical Analysis: Conduct spatial and temporal analysis. This may involve:

- Creating time-series plots for each location.

- Performing Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) to test for significant differences between sites.

- Generating spatial interpolation maps (e.g., Kriging) to visualize microclimate patterns.

- Community Workshop: Present findings to the community using clear visualizations. Facilitate a discussion on the ecological implications and potential advocacy or management actions based on the data.

Challenges and Mitigation Strategies

Despite their promise, open-source technologies face significant challenges in real-world deployment, particularly in vulnerable contexts. Understanding these hurdles is the first step to overcoming them.

The Digital Divide: Disparities in internet access, digital literacy, and technological infrastructure can exclude the most marginalized communities [21]. Mitigation: Invest in offline-capable tools and data literacy empowerment programs that are co-developed with the community. Use low-power, long-range (LoRa) communication protocols where cellular networks are unreliable [26] [23].

Data Overload and Complexity: The continuous data streams from sensor networks can be overwhelming [26]. Mitigation: Implement edge processing to pre-analyze data and trigger alerts only for significant events [23]. Develop user-friendly dashboards that translate raw data into actionable insights, as done in platforms like batmonitoring.org [27].

Sensor Maintenance and Degradation: Long-term deployment in harsh environments leads to sensor drift and failure [26]. Mitigation: Establish a community-based maintenance protocol with clear roles. Use modular designs for easy part replacement. Conduct regular (e.g., quarterly) recalibration checks [22].

Interoperability and Data Standards: Fragmented data formats make it difficult to combine datasets from different projects [26] [27]. Mitigation: Adopt existing open data standards (e.g., from OGC, W3C) from the outset. Participate in initiatives like the European BioAgora project, which aims to map and harmonize biodiversity data workflows for policy use [27].

Ethical Risks and Data Sovereignty: Open data can be misused for surveillance, or data on community resources could be exploited by external actors [21] [26]. Mitigation: Develop clear data governance agreements with the community that define data ownership, access, and use. Practice "Free, Prior, and Informed Consent" (FPIC) for data collection.

The integration of low-cost, open-source technologies is fundamentally reshaping the landscape of ecological monitoring, transforming vulnerable communities from passive subjects of study into active agents of environmental stewardship. The tools and protocols detailed in this guide—from validated sensor designs and accessible AI platforms to community-centric workflows—provide a robust technical foundation for researchers to support this transformation. The evidence is clear: open-source solutions can produce research-grade data, and when coupled with a deep commitment to equity and capacity building, they can redress long-standing power imbalances in environmental knowledge.

The future trajectory of this field points towards greater integration, intelligence, and interoperability. Key trends include:

- Adaptive AI: Projects like the NSF-funded grant to develop adaptable AI systems for biodiversity monitoring are pioneering methods that optimize data collection in real-time, focusing resources on the most informative locations and periods [20].

- Multi-layered Sensing: The fusion of ground-based sensor data with drone and satellite imagery (e.g., the Nature 4.0 project) will provide a more holistic view of ecosystem dynamics [26].

- Policy Integration: There is a growing push, as seen in EU biodiversity monitoring projects, to harmonize data from novel technologies like eDNA and bioacoustics with policy frameworks, creating a direct pipeline from community-gathered data to conservation action [27].

For researchers and scientists, the imperative is to engage not merely as technical implementers but as partners in capacity building. The ultimate success of these technologies will not be measured by the volume of data collected, but by the extent to which they are owned, understood, and utilized by communities to secure their environmental rights, restore their ecosystems, and build resilience in a rapidly changing world.

The escalating global biodiversity crisis demands innovative, scalable, and cost-effective monitoring solutions. Traditional ecological monitoring methods often rely on proprietary, expensive instrumentation, creating significant barriers to comprehensive data collection, especially for researchers and communities with limited funding. In response, a paradigm shift towards low-cost, open-source technologies is fundamentally transforming ecological research. This movement is championed by key communities of practice that foster collaboration, develop accessible tools, and democratize environmental science. This guide provides an in-depth technical analysis of three pivotal organizations—EnviroDIY, Conservation X Labs (CXL), and WILDLABS—detailing their unique roles in advancing open-source ecological monitoring. By providing structured comparisons, experimental methodologies, and practical toolkits, this document serves as a comprehensive resource for researchers and scientists integrating these communities' outputs into rigorous scientific practice.

Community Profiles and Comparative Analysis

This section delineates the core attributes, missions, and quantitative impacts of EnviroDIY, Conservation X Labs, and WILDLABS, providing a foundational understanding of their respective niches within the conservation technology ecosystem.

Table 1: Core Profiles of EnviroDIY, Conservation X Labs, and WILDLABS

| Feature | EnviroDIY | Conservation X Labs (CXL) | WILDLABS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Mission | To provide low-cost, open-source hardware/software solutions for DIY environmental monitoring, particularly of fresh water [28] [29] [30]. | To prevent the sixth mass extinction by developing and deploying transformative technological solutions to address extinction's underlying drivers [31] [32]. | To serve as a central online hub connecting conservation tech professionals globally to share ideas, answer questions, and collaborate [33] [34]. |

| Core Approach | Community-driven sharing of DIY ideas, designs, and protocols; development of open-source hardware like the Mayfly Data Logger [29]. | A multi-faceted approach including open innovation prizes, in-house invention, and field deployment of cutting-edge technology [31] [35]. | Facilitating community discussion, knowledge sharing through forums, virtual meetups, and tech tutorials; publishing state-of-the-field research [33] [34]. |

| Key Outputs | Open-source sensor designs, data loggers (Mayfly), software libraries, and detailed build tutorials [28] [29]. | A portfolio of supported innovations (e.g., AudioMoth, ASM Progress App), prizes, and direct field interventions [35]. | Annual trends reports, community forums, curated educational content, and networking opportunities [34]. |

| Governance | An initiative of the Stroud Water Research Center [30]. | An independent non-profit organization [31]. | A platform under the WILDLABS network [33]. |

Table 2: Quantitative Impact and Engagement Metrics

| Metric | EnviroDIY | Conservation X Labs | WILDLABS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reported Innovations Supported | N/A | 177+ game-changing innovations supported [35]. | N/A |

| Funding Dispersed | N/A | $12M+ to breakthrough solutions [35]. | N/A |

| Community Scale | Public community forums with member registration [28]. | N/A | The go-to online hub for conservation technology, with measurable impact on member collaboration and learning [34]. |

| Technology Focus Areas | Water quality sensors, dataloggers, solar-powered monitoring stations [29]. | AI, biologgers, networked sensors, DNA synthesis, invasive species management, anti-extraction technologies [31] [35]. | All conservation tech, with rising engagement in AI, data management tools, biologgers, and networked sensors [34]. |

The following diagram illustrates the typical workflow and interaction points for a researcher engaging with these three communities to develop and deploy a low-cost monitoring solution.

Diagram 1: Researcher Workflow Across Communities

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Deploying an Open-Source Water Quality Monitoring Station

This protocol, adapted from EnviroDIY's methodologies, details the assembly and deployment of a low-cost, solar-powered station for measuring parameters like conductivity, temperature, and turbidity [22] [29].

1. Hardware Assembly and Programming:

- Core Logger: Utilize the Mayfly Data Logger, the open-source core designed for environmental sensing [29].

- Sensor Integration: Connect sensors via solderless jumper wires or custom shields. Typical sensors include:

- Conductivity/Temperature/Depth (CTD) sensor.

- Turbidity sensor.

- Power System: Attach a 3.7V LiPo battery and a 6V, 1W solar panel for continuous, off-grid operation [29].

- Software Setup: Program the Mayfly using the Arduino IDE with the EnviroDIY

ModularSensorslibrary, which handles sensor polling, data logging, and power management [28].

2. Calibration and Validation:

- Laboratory Calibration: Calibrate sensors against known standards prior to deployment.

- Field Validation: Co-locate the DIY station with a research-grade commercial system (e.g., from YSI or Campbell Scientific) for a parallel run period [22].

- Data Correlation: Perform linear regression analysis between the DIY and commercial system readings. A strong correlation (R² ≥ 0.97 for temperature and humidity) validates the DIY system's performance [22].

3. Field Deployment:

- Installation: Secure the station in a stream using a staff gauge mount. Ensure sensors are submerged at the correct depth and the solar panel has clear sunlight exposure [29].

- Configuration: Set the logging interval (e.g., every 15 minutes) and, if used, the cellular or satellite transmission interval to conserve power [28] [29].

Case Study: Performance and Cost Analysis of Open-Source Dataloggers

A critical step in integrating open-source tools into formal research is empirical validation. The following protocol outlines a methodology for testing the performance and cost-effectiveness of open-source dataloggers against commercial options, as demonstrated in peer-reviewed literature [22].

Objective: To evaluate the accuracy, reliability, and cost-effectiveness of open-source environmental monitoring systems compared to commercial-grade instrumentation in forest ecology applications.

Experimental Design:

- Site Selection: Establish multiple monitoring plots across a gradient of environmental conditions (e.g., under canopy vs. open areas, different elevations).

- Instrumentation: At each plot, install:

- Treatment Group: Custom, open-source monitoring system (e.g., based on the Mayfly logger) measuring temperature and relative humidity.

- Control Group: Co-located, research-grade commercial datalogger (e.g., HOBO from Onset).

- Data Collection: Log data simultaneously from all systems at a high temporal resolution (e.g., every 5 minutes) over a period of at least one month to capture diurnal and seasonal cycles.

- Data Analysis:

- Accuracy & Precision: Calculate the coefficient of determination (R²), root mean square error (RMSE), and mean bias error (MBE) between the open-source and commercial sensor readings.

- Cost Analysis: Tabulate the total cost of components for the open-source system and compare it to the retail price of the commercial system. Calculate cost as a percentage savings.

Key Findings from precedent studies:

- Accuracy: Open-source dataloggers can achieve performance highly correlated with commercial options, with R² values of 0.97 or higher for temperature and humidity [22].

- Cost: The primary advantage is significant cost reduction, with open-source systems costing between 13% and 80% of comparable commercial systems, enabling greater scalability [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Open-Source Research Reagents

This section catalogues critical hardware, software, and platforms that form the foundational "reagents" for experiments and deployments in low-cost, open-source ecological monitoring.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Open-Source Ecological Monitoring

| Item Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mayfly Data Logger [29] | Hardware | An open-source, programmable microcontroller board that serves as the core for connecting, powering, and logging data from various environmental sensors. | Provides the central nervous system for custom sensor stations, enabling precise timing, data storage, and remote communication. |

| ModularSensors Library [28] | Software | An Arduino library designed to work with the Mayfly, simplifying the code required to interact with over 50 different environmental sensors and manage power and data logging. | Drastically reduces software development time, standardizes data output, and enhances reproducibility across research projects. |

| AudioMoth 2 [35] | Hardware | A low-cost, full-spectrum acoustic logger developed by Open Acoustic Devices and supported by CXL's innovation pipeline. | Enables large-scale bioacoustic monitoring for species identification, behavior studies, and ecosystem health assessment. |

| EnviroDIY Community Forum [28] [30] | Platform | An online community where users post questions, share project builds, and troubleshoot technical issues. | Functions as a collaborative knowledge base for problem-solving and peer-review of technical designs, crucial for protocol debugging. |

| WILDLABS Tech Tutors [33] | Platform | A series of instructional videos and interactive sessions where experts teach specific conservation tech skills. | Accelerates researcher learning curves for complex topics like AI analysis, sensor repair, and data management. |

Discussion: Trends, Challenges, and Future Directions

The conservation technology landscape is dynamic. WILDLABS' annual survey data reveals critical trends and persistent challenges that researchers must navigate [34].

Key Technological Trends:

- Rising Engagement: AI tools, data management platforms, biologgers, and networked sensors are experiencing the most significant growth in user and developer engagement [34].

- Shifting Perceptions: The technologies with the highest perceived untapped potential are evolving. Biologgers, networked sensors, and AI tools are now at the forefront, while engagement with earlier tools like eDNA has matured and normalized [34].

- Accessibility Drive: A dominant trend fueling optimism is the increasing accessibility and interoperability of tools and data, a core mission of the open-source movement [34].

Persistent Sector-Wide Challenges:

- Funding and Duplication: Competition for limited funding and duplication of efforts remain the most severe challenges, highlighting the need for coordinated initiatives and open-source collaboration [34].

- Skill Gaps: Matching technological expertise to conservation challenges has emerged as a top-tier concern, underscoring the importance of communities like WILDLABS that bridge these disciplines [34].

- Inequitable Access: Constraints on engagement are not uniformly distributed. Researchers in developing economies and women report facing disproportionately significant barriers, indicating a critical area for continued focus and resource allocation [34].

EnviroDIY, Conservation X Labs, and WILDLABS collectively form a powerful, complementary ecosystem driving the open-source revolution in ecological monitoring. EnviroDIY provides the foundational, buildable hardware and protocols; Conservation X Labs acts as an innovation engine, spotlighting and scaling high-impact technologies; and WILDLABS serves as the essential connective tissue, fostering a global community of practice. For the modern researcher, engaging with these communities is no longer optional but integral to conducting cutting-edge, cost-effective, and scalable ecological research. By leveraging their shared knowledge, validated tools, and collaborative networks, scientists can accelerate the development and deployment of monitoring solutions that match the scale and urgency of the global biodiversity crisis.

From Theory to Field: Implementing Open-Source Monitoring Systems

The advent of low-cost, open-source hardware platforms has fundamentally transformed the landscape of ecological monitoring research. These technologies have democratized data collection, enabling researchers and citizen scientists to deploy high-density sensor networks that generate scientific-grade data at a fraction of traditional costs. Platforms such as Arduino, Raspberry Pi, and specialized boards like the EnviroDIY Mayfly Data Logger form a technological ecosystem that balances performance, power efficiency, and connectivity for diverse environmental applications. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of these core building blocks, presents structured experimental protocols, and validates data quality through comparative studies, establishing a foundational framework for their application in rigorous scientific research and drug development environmental assessments.

Hardware Platform Analysis

The selection of a core hardware platform is dictated by the specific requirements of the ecological study, including power availability, sensor complexity, data processing needs, and connectivity.

Table 1: Core Hardware Platform Comparison for Ecological Monitoring

| Platform | Core Features & Architecture | Power Consumption | Typical Cost (USD) | Ideal Research Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arduino (e.g., Uno, MKR) | Microcontroller (MCU) based, single-task operation, analog inputs, low-clock speed. | Very Low (mA range), deep sleep modes (~µA) [36] | $20 - $50 [37] | Long-term, battery-powered spot measurements (e.g., soil moisture, water level) [10] [38]. |

| Raspberry Pi | System-on-Chip (SoC), runs full OS (e.g., Linux), multi-tasking, high-clock speed, WiFi/Bluetooth. | High (100s of mA to Amps), requires complex power management [39] | $35 - $75 | On-device data processing, camera trap image analysis, real-time dashboards, complex sensor fusion [39] [5] [40]. |

| Specialized Boards (EnviroDIY Mayfly) | MCU-based (Arduino-compatible), integrated real-time clock, SD card, solar power circuitry, ultra-low-power modes. | Very Low, optimized for multi-year deployment with solar cell [37] [41] | ~$65 [37] | High-quality, continuous field monitoring (water quality, weather stations) with cellular telemetry [42] [41]. |

The architectural differences dictate their use cases. Microcontroller-based units like the Arduino and EnviroDIY Mayfly excel in dedicated, low-power tasks and are programmed for specific, repetitive operations like reading sensors at intervals and logging data [36] [37]. In contrast, the Raspberry Pi operates as a full computer, capable of running complex software stacks, processing images from camera traps in real-time using AI models, and serving web pages for data visualization [39] [5]. The EnviroDIY Mayfly represents a domain-optimized platform, incorporating features essential for professional environmental monitoring—such as precise timing and robust power management—directly onto the board, reducing the need for external shields and modules [37].

Figure 1: Decision workflow for selecting a core hardware platform based on research constraints.

Essential Sensors and Research Reagents

The utility of a hardware platform is realized through its integration with environmental sensors. These sensors act as the "research reagents" of field studies, generating the quantitative data points for analysis.

Table 2: Essential "Research Reagent" Sensors for Ecological Monitoring

| Sensor Category | Specific Models | Measured Parameters | Accuracy & Communication Protocol | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature/Humidity | DHT11, DHT22, BME280 | Air Temperature, Relative Humidity | DHT11: ±2°C, ±5% RH; Digital Signal [36] | Baseline microclimate characterization; input for evapotranspiration models. |

| Barometric Pressure | BMP280, BME280 | Atmospheric Pressure | ±1 hPa; I2C/SPI [36] | Weather forecasting, altitude correction for gas sensors. |

| Air Quality | MQ-135 (Gases), PMS5003 (Particulate) | CO2, NH3, NOx; PM2.5, PM10 | Requires calibration; Analog (MQ) / UART (PMS) [36] | Tracking pollution gradients, assessing environmental impact on ecosystem health. |

| Water Quality | Meter Group CTD, Campbell OBS3+ | Conductivity, Temperature, Depth, Turbidity | Factory Calibration; SDI-12, Analog [41] | Gold-standard for water quality studies; assessing eutrophication, sediment load. |

| Soil Moisture | Capacitive Soil Moisture Sensor | Volumetric Water Content | Requires soil-specific calibration; Analog [38] | Irrigation scheduling, plant health and productivity studies. |

| Light/UV | LDR (Light Dependent Resistor), ML8511 | Light Intensity, UV Index | Requires calibration; Analog [36] | Studying photodegradation, plant photosynthesis rates, animal activity patterns. |

Experimental Protocol: Validation of Low-Cost Water Quality Sensors

A critical step in employing open-source platforms is the validation of collected data against established scientific instruments. The following protocol details a methodology for comparing EnviroDIY-based sensor data against U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) streamgage data, as performed in a peer-reviewed context [41].

Objective

To determine the accuracy and long-term reliability of water quality parameters (temperature, conductivity, depth, turbidity) collected using an EnviroDIY Mayfly Data Logger and Meter Group CTD sensor against reference measurements from a co-located USGS streamgage equipped with an In-Situ Aqua TROLL sensor.

Materials and Setup

- Test Station: EnviroDIY Mayfly Data Logger [37] powered by solar cell and battery.

- Test Sensors: Meter Group CTD sensor (temperature, conductivity, depth) and Campbell OBS3+ Turbidity Sensor, used with factory calibrations [41].

- Reference Station: USGS streamgage with In-Situ Aqua TROLL sensor.

- Data Portal: Monitor My Watershed for data storage and retrieval [37].

Methodology

- Site Selection and Co-location: Identify a monitoring location with an existing USGS streamgage. Deploy the EnviroDIY monitoring station immediately adjacent to the USGS sensor suite to ensure both systems are measuring the same water body under identical hydraulic and environmental conditions [41].

- Sensor Configuration and Deployment: Program the Mayfly datalogger to record measurements at 15-minute intervals, matching the USGS data logging interval. Securely mount all sensors to a fixed, stable structure to minimize movement and vibration.

- Data Collection Period: Conduct continuous data collection for a period of 2 to 5 years. This extended duration is crucial for capturing a wide range of environmental conditions, including baseflow, storm events, and seasonal variations [41].

- Data Retrieval and Quality Control: After the deployment period, download the raw data from both the Monitor My Watershed portal (EnviroDIY data) and the USGS National Water Information System (NWIS) web interface. Subject both datasets to standardized quality control checks to remove obvious outliers or erroneous readings caused by sensor fouling or debris impact.

- Data Alignment and Analysis: Align the two datasets by their 15-minute timestamps. Calculate the difference between the EnviroDIY and USGS readings for each parameter at each interval. Perform statistical analysis (e.g., mean difference, root-mean-square error (RMSE), and linear regression) to quantify agreement and identify any systematic bias or drift over time [41].

Figure 2: Workflow for validating low-cost water quality sensors against a reference station.

Results and Interpretation

A study following this protocol found that temperature data from the EnviroDIY station showed less than 1°C difference from the USGS data, demonstrating high accuracy for this parameter [41]. This validates the use of low-cost systems for precise temperature monitoring. However, performance for some parameters, like turbidity, showed greater divergence, particularly during high-flow storm events, and some sensors exhibited performance deterioration over time [41]. This indicates that:

- Validation is parameter-specific: Not all sensors perform equally.

- Sensor lifecycle management is critical: The study suggests a sensor replacement or recalibration schedule of approximately three years for sustained data quality [41].

- Protocol refinement: Calibrating both the test and reference sensors to the same standard could improve the agreement for more complex parameters like turbidity [41].

Data Management and Telemetry Architecture

The ability to handle the data generated by these systems is a cornerstone of their scientific utility. A push-based architecture, as implemented in the ODM2 Data Sharing Portal, provides a robust solution for data consolidation from distributed sensor networks [37].

In this architecture, field-deployed dataloggers (e.g., Arduino/Mayfly with cellular or WiFi connectivity) are programmed to periodically push sensor data as HTTP POST requests to a central web service API [37]. This data, along with critical metadata, is then validated and stored in a structured database implementing a standard data model like ODM2. The stored data can then be visualized through web-based dashboards, downloaded in standard formats (e.g., CSV), or accessed programmatically via machine-to-machine web services for further analysis [37]. This entire stack is open-source, allowing research institutions to deploy their own centralized data repositories.

The integration of Arduino, Raspberry Pi, and specialized boards like the EnviroDIY Mayfly provides a versatile, validated, and cost-effective technological foundation for advanced ecological monitoring. By carefully selecting the platform based on power and processing needs, employing a robust sensor validation protocol, and implementing a scalable data management architecture, researchers can generate high-quality, scientific-grade data. This approach not only accelerates environmental research and drug development impact assessments but also democratizes science by lowering the financial barriers to sophisticated environmental sensing.

The advent of low-cost, open-source technologies is fundamentally transforming the field of ecological monitoring research. These advancements are democratizing environmental data collection, enabling researchers, scientists, and institutions with limited budgets to deploy high-density sensor networks for precise, long-term studies. Traditional environmental monitoring systems often involve proprietary, expensive equipment that can be cost-prohibitive for large-scale or long-term deployments. The emergence of open-source hardware and software solutions, coupled with affordable yet accurate sensors, is breaking down these barriers. This paradigm shift allows for unprecedented spatial and temporal data resolution in critical areas such as air quality, water quality, and microclimate assessment, facilitating a more granular understanding of ecological dynamics and human impacts on the environment.

This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of the core sensor types, their operational principles, and methods for their integration into robust, research-grade monitoring systems. The content is framed within the context of leveraging low-cost, open-source technologies to advance ecological research. We will explore specific sensor technologies for each environmental domain, detail integration methodologies using single-board computers and microcontrollers, and present structured data management and analysis protocols. The focus remains on practical, implementable solutions that maintain scientific rigor while minimizing costs, thereby empowering a wider research community to contribute to and benefit from advanced environmental monitoring.

Sensor Types and Their Technical Specifications

Environmental monitoring relies on a suite of specialized sensors, each designed to detect specific physical or chemical parameters. Understanding the underlying technology, performance characteristics, and limitations of each sensor type is crucial for designing effective monitoring systems. The selection of sensors involves a careful balance between cost, accuracy, power consumption, longevity, and suitability for the intended environmental conditions. This section provides a technical overview of the primary sensor categories used in air quality, water quality, and microclimate studies, with an emphasis on technologies that are amenable to low-cost, open-source platforms.

Air Quality Sensors

Air quality sensors detect and quantify various gaseous and particulate pollutants. Their working principles vary significantly based on the target analyte.

Particulate Matter (PM) Sensors: These sensors typically employ optical methods. A laser diode illuminates airborne particles, and a photodetector measures the intensity of the scattered light, which correlates to the concentration of particles in specific size ranges (e.g., PM2.5 and PM10). Sensors like the Plantower PMS5003 are widely used in open-source projects for their balance of cost and reliability [43].