Comparative Ecological Network Analysis: Methods, Applications, and Future Directions

This article provides a comprehensive overview of comparative ecological network analysis methods, addressing the critical need for robust frameworks in ecosystem management.

Comparative Ecological Network Analysis: Methods, Applications, and Future Directions

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of comparative ecological network analysis methods, addressing the critical need for robust frameworks in ecosystem management. It explores foundational theories, details prominent methodological approaches like circuit theory and least-cost path analysis, and discusses optimization strategies for enhanced network performance. Through validation techniques and comparative studies, the article evaluates model effectiveness in diverse ecological contexts. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and environmental professionals, this synthesis identifies current methodological limitations and future research trajectories for advancing ecological network science in rapidly changing environments.

Theoretical Foundations and Evolving Concepts in Ecological Network Analysis

The integration of landscape ecology and network theory has fundamentally transformed how researchers analyze complex ecological systems. This conceptual merger represents a significant paradigm shift in ecology, moving from a primarily descriptive science to a predictive one capable of handling immense complexity. Landscape ecology emerged with a focus on spatial patterning, examining how the arrangement of ecosystems and land forms influences ecological processes. Network theory provided the mathematical foundation to quantify relationships between landscape elements, transforming abstract spatial concepts into analyzable systems of nodes and links. This convergence has enabled scientists to address pressing global challenges, from biodiversity conservation to sustainable urban planning, with unprecedented analytical rigor. The resulting framework of ecological network analysis now serves as a powerful interdisciplinary tool across diverse fields, including landscape planning, pharmaceutical research, and environmental management [1] [2] [3].

This article traces the historical trajectory of this integration, compares the methodological approaches that have emerged, and demonstrates through case studies and experimental data how these methods are applied in contemporary research settings. We examine how traditional landscape ecology metrics have evolved into sophisticated network properties, and how this evolution has enhanced our ability to predict ecosystem behavior under various environmental scenarios.

Historical Trajectory and Theoretical Foundations

The Evolution of Landscape Ecology

Landscape ecology developed as a distinct discipline in the latter half of the 20th century, emphasizing the spatial heterogeneity of environments and how this patterning affects ecological processes. Early landscape ecologists focused on patch dynamics, corridors, and matrix interactions, conceptualizing landscapes as mosaics of interacting elements. This spatial perspective was fundamentally qualitative in its infancy, relying heavily on cartographic representations and descriptive ecology. The introduction of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) in the 1980s and 1990s revolutionized the field, enabling researchers to quantitatively analyze spatial patterns through landscape metrics such as patch size, shape complexity, and connectivity indices. This quantitative shift set the stage for integration with network theory, as these landscape elements naturally corresponded to the nodes and links of mathematical graphs [4].

The Adoption of Network Theory in Ecology

Network theory entered ecology through multiple pathways. Early ecological applications focused on food webs, representing feeding relationships as networks to study energy flow and ecosystem stability. Theoretical ecologists like Robert May pioneered this approach in the 1970s, exploring how network properties like connectance influenced ecosystem stability. This research revealed the counterintuitive finding that complex ecosystems could be less stable, challenging prior assumptions about the relationship between diversity and stability. Parallel developments in social network analysis and infrastructure network modeling provided additional analytical tools that ecologists adapted for studying ecological systems. The critical theoretical advance was recognizing that ecological interactions—whether trophic, mutualistic, or spatial—could be abstracted as networks, allowing the application of mathematical graph theory to biological systems [2] [3].

Table 1: Key Historical Developments in Ecological Network Analysis

| Time Period | Development in Landscape Ecology | Development in Network Theory | Integrative Milestones |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1970s-1980s | Focus on patch dynamics and island biogeography | Food web structure analysis; Stability-complexity debate | Recognition of spatial patterns as networks |

| 1990s-2000s | GIS adoption; Landscape metrics development | Graph theory applications; Centrality measures | Circuit theory; Least-cost path modeling |

| 2010s-Present | Multi-scale analysis; Remote sensing integration | Multilayer networks; Dynamic network models | Integrated socio-ecological network frameworks |

Theoretical Integration: From Spatial Patterns to Networks

The theoretical integration of landscape ecology and network theory represents more than merely applying new analytical tools to existing problems. It constitutes a fundamental conceptual shift in how ecological systems are understood. Where traditional landscape ecology treated patches, corridors, and matrices as distinct elements, the network perspective reconceptualizes them as interconnected components of an integrated system. This shift enables researchers to apply formal mathematical concepts like degree distribution (the distribution of connections per node), clustering coefficients (the degree to which nodes cluster together), and modularity (the extent to which a network is organized into subgroups) to spatial ecological systems. These network properties provide insights into ecosystem functioning that were inaccessible through traditional landscape metrics alone, particularly regarding robustness, vulnerability, and functional connectivity [2] [3].

Comparative Methodological Approaches

Ecological Source Identification Methods

A critical methodological distinction in ecological network analysis lies in how researchers identify ecological sources (key patches that serve as network nodes). The search results reveal two predominant approaches with distinct strengths and limitations, as exemplified by the Nanchang case study [1].

Table 2: Comparison of Ecological Source Identification Methods

| Method Characteristic | Area Threshold Method | CMSPACI Method |

|---|---|---|

| Basic Principle | Selection based primarily on patch size | Integration of morphological spatial pattern analysis with landscape connectivity indices |

| Implementation Complexity | Low; relatively simple to apply | High; requires multiple analytical steps |

| Connectance Consideration | Limited; focuses on individual patches | Comprehensive; evaluates patch relationships |

| Resulting Network Connectivity | Lower; sources may be isolated | Higher; sources maintain functional connections |

| Habitat Quality of Corridors | Less optimal | Better quality corridors |

| Typical Application | Preliminary screening; resource-limited studies | Comprehensive conservation planning |

The area threshold method represents a more traditional landscape ecology approach, identifying ecological sources based primarily on patch size. While methodologically straightforward, this approach often identifies sources with low landscape connectivity that may be functionally isolated within the broader ecological matrix. In contrast, the CMSPACI method (Combining Morphological Spatial Pattern Analysis and Connectivity Indices) represents a more sophisticated integration of landscape and network approaches, identifying sources based on both their structural attributes and their functional relationships with other landscape elements. Research from Nanchang demonstrates that CMSPACI-identified sources exhibit superior habitat quality in corridors and stronger interaction intensity between patches, though the method demands greater analytical resources [1].

Analytical Framework for Network Comparison

When comparing ecological networks across environmental gradients or management scenarios, researchers employ standardized analytical frameworks. The search results highlight several methodological considerations for robust network comparison [5]:

Selection of Network Properties: Researchers must carefully choose which network properties to compare based on their research questions. Common properties include connectance (proportion of possible interactions realized), nestedness (degree to which specialists interact with subsets of generalists' partners), modularity (compartmentalization), and degree distribution.

Standardization Approaches: Different standardization methods can significantly influence conclusions about network variation:

- Direct comparison of raw metric values

- Null model standardization comparing observed networks to random expectations

- Trait-based analysis examining the role of functional traits in driving network structure

Spatial Explicit Methods: In landscape applications, networks are often constructed using resistance surfaces based on land cover, elevation, or other environmental variables. The Minimum Cumulative Resistance (MCR) model is frequently employed to identify potential ecological corridors between sources by calculating the least-resistant pathways through the landscape matrix [4].

Case Studies and Experimental Applications

Urban Ecological Network Planning: Nanchang and Fuzhou

The practical application of integrated landscape-network approaches is exemplified in urban ecological planning. In the Nanchang case study, researchers directly compared the area threshold and CMSPACI methods for ecological network construction. Their findings demonstrated that while both methods identified similar numbers of ecological barriers (primarily roads and construction land), the CMSPACI approach produced networks with superior functional connectivity and more realistic corridor placements. This study highlighted how methodological choices in source identification propagate through subsequent network analyses, influencing conservation recommendations and planning outcomes [1].

The Fuzhou case study illustrates a comprehensive application of ecological network analysis to green space system planning. Researchers employed a multi-step methodology:

- Landscape pattern evaluation using Fragstats software to calculate landscape metrics

- Green Protected Area (GPA) classification based on Conefor connectivity analysis

- Ecological corridor identification using the Minimum Cumulative Resistance model in ArcGIS

- Strategic node identification through gravity modeling and network analysis

This integrated approach allowed planners to identify key connectivity elements in the urban landscape, including the Min River corridor and coastal wetlands as strategically vital despite spatial constraints. Scenario analysis revealed that an optimized network configuration could increase system cyclicity from 1.00 to 4.18, significantly enhancing resource recycling potential—a key ecosystem function. This case demonstrates how traditional landscape analysis tools like Fragstats can be seamlessly integrated with network analysis to support evidence-based urban planning [4].

Pharmaceutical Research Applications

Network approaches have transcended traditional ecology to impact pharmaceutical research, demonstrating the broad utility of these methods. Researchers have constructed multilayer networks incorporating drug pipeline layers, global supply chain layers, and ownership layers to understand knowledge flow in drug development. This approach reveals how bow-tie structures and community detection can identify patterns in complex research and development processes that would remain invisible through traditional analysis. The application of network methods to pharmaceutical research represents a significant extension of ecological network principles to socio-technical systems, highlighting the cross-disciplinary fertilisation of these ideas [6] [7].

Table 3: Network Properties and Their Ecological and Pharmaceutical Interpretations

| Network Property | Ecological Interpretation | Pharmaceutical Application |

|---|---|---|

| Connectance | Proportion of possible species interactions realized | Density of collaboration between institutions |

| Modularity | Degree of compartmentalization into subsystems | Specialization in therapeutic areas |

| Node Centrality | Importance of species in maintaining network function | Key organizations in knowledge flow |

| Nestedness | Structured specialization in mutualistic networks | Pattern of innovation adoption |

Contemporary ecological network analysis requires specialized analytical tools and data resources. The search results reveal a consistent toolkit employed across multiple studies:

Table 4: Essential Resources for Ecological Network Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fragstats | Software | Landscape pattern analysis | Calculating landscape metrics for habitat patches [4] |

| Conefor | Software | Connectivity analysis | Determining importance of habitat patches (dPC) [4] |

| ArcGIS | Software platform | Spatial analysis and modeling | Implementing Minimum Cumulative Resistance models [4] |

| Graph Theory Libraries | Analytical framework | Network metric calculation | Analyzing degree distribution, modularity [2] |

| Cortellis Database | Data source | Pharmaceutical pipeline information | Constructing drug development networks [6] |

| Remote Sensing Data | Data source | Land cover classification | Creating resistance surfaces for corridor modeling [4] |

Conceptual Framework and Analytical Workflow

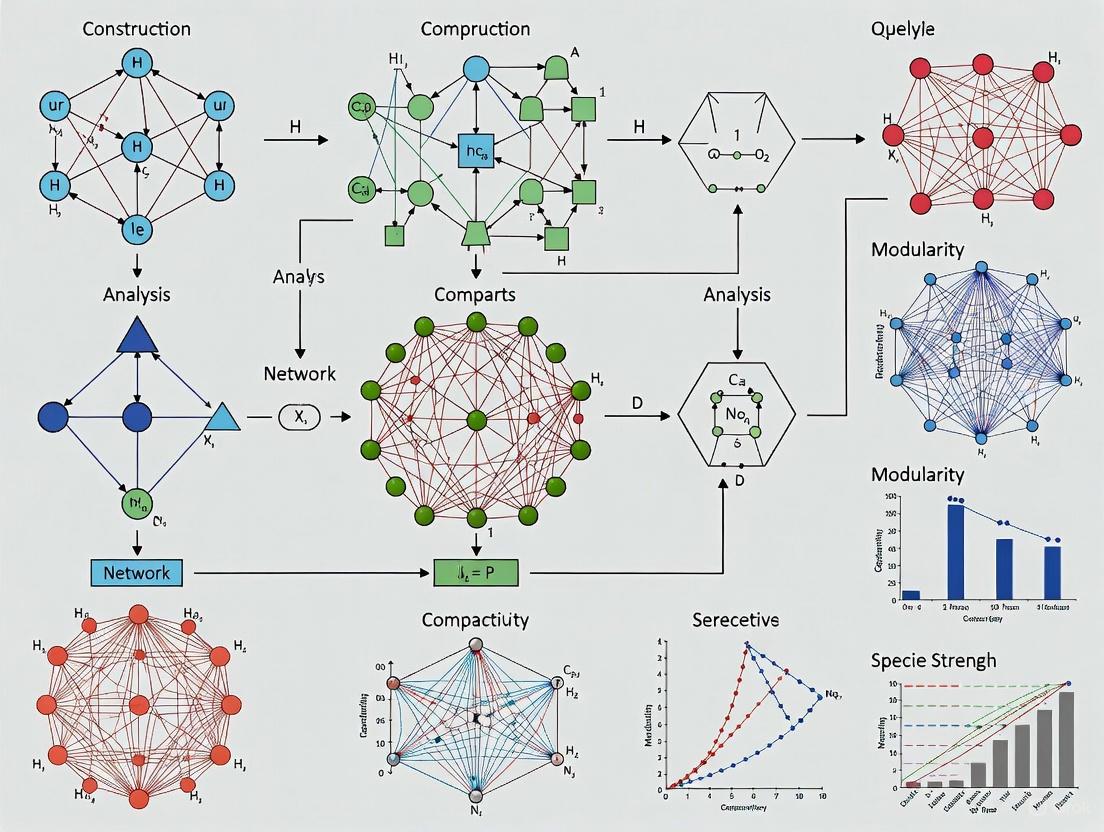

The integration of landscape ecology and network theory follows a consistent conceptual framework that can be visualized as a sequential analytical process. The diagram below illustrates this workflow from data collection through to application:

Ecological Network Analysis Workflow

The integration of landscape ecology and network theory represents more than a methodological advancement—it constitutes a fundamental shift in how we understand and analyze ecological complexity. This synthesis has enabled a transition from descriptive ecology to predictive science, allowing researchers to forecast system responses to perturbations, identify critical leverage points for intervention, and optimize conservation strategies across scales. The comparative analysis presented here demonstrates that methodological choices significantly influence research outcomes, with more integrated approaches like the CMSPACI method generally producing ecologically realistic networks despite their computational complexity.

Future developments in this field will likely focus on dynamic networks that incorporate temporal variation, multilayer networks that capture different types of interactions simultaneously, and tighter integration with remote sensing technologies for automated network generation. As these methods continue to mature and cross disciplinary boundaries—from urban planning to pharmaceutical development—their value in addressing complex socio-ecological challenges will only increase. The historical development from landscape ecology to network theory has positioned ecology as an increasingly quantitative, predictive science capable of informing critical decisions about biodiversity conservation and ecosystem management in an increasingly human-modified world.

Ecological network analysis provides a powerful framework for understanding and managing the complex interactions within ecosystems. By representing landscapes as interconnected networks, researchers and conservation professionals can identify critical areas for maintaining biodiversity, supporting species movement, and ensuring ecosystem resilience. This comparative guide examines the three core technical components of ecological network analysis: ecological sources (habitat patches), corridors (linkages between habitats), and resistance surfaces (landscape permeability maps). These components form the foundational architecture of ecological connectivity models used in conservation planning, environmental impact assessment, and regional development strategies. Understanding the methodological choices available for each component and their performance implications is essential for effective ecological network design and implementation, particularly in fragmented landscapes where habitat connectivity directly influences species persistence and ecosystem function.

Comparative Analysis of Core Components

The construction of ecological networks requires careful selection of methodologies for each core component, with significant implications for analytical outcomes and conservation effectiveness. Different approaches offer distinct advantages and limitations across key performance criteria including ecological accuracy, data requirements, computational intensity, and practical applicability.

Table 1: Methodological Comparison for Identifying Ecological Sources

| Method | Key Features | Data Requirements | Ecological Basis | Best Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Approaches (MSPA) | Identifies sources based on spatial pattern and configuration; objective and repeatable [8] | Land cover/Land use raster data | Landscape connectivity theory; assumes structural connectivity supports functional connectivity | Initial screening in data-poor regions; large-scale assessments |

| Functional Approaches (RSEI, Habitat Quality) | Assesses ecological quality using multiple indicators (greenness, humidity, heat, dryness) [8] [9] | Remote sensing data (NDVI, LST, WET, NDBSI); field validation data | Ecosystem service provision; habitat suitability | Priority conservation areas; quality-focused planning |

| Composite "Structure-Function" Approach | Integrates MSPA with RSEI/habitat quality assessment; captures both form and function [8] | Land cover data + multi-spectral remote sensing data | Combined structural and functional connectivity theory | Comprehensive planning; optimizing limited conservation resources |

Table 2: Methodological Comparison for Constructing Corridors

| Method | Underlying Principle | Connectivity Assumption | Output Characteristics | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Least-Cost Path (LCP) | Identifies single optimal path with minimum cumulative resistance between sources [10] | Organisms have perfect landscape knowledge and choose optimal routes | Discrete, linear corridors; single best pathway | Computationally efficient; may oversimplify movement ecology |

| Circuit Theory | Models landscape connectivity as electrical current flow with random walk behavior [8] | Organisms move randomly through landscapes based on resistance | Probabilistic current density maps; multiple potential pathways | Identifies pinch points and barriers; more computationally intensive |

| Minimum Cumulative Resistance (MCR) | Calculates cumulative cost from sources across resistance surface [11] [4] | Movement cost minimization drives connectivity patterns | Continuous resistance values from sources; cost-weighted distances | Flexible application; integrates well with GIS analysis |

Table 3: Methodological Comparison for Developing Resistance Surfaces

| Method | Development Process | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Validation Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expert Opinion | Expert scoring of land cover types based on perceived permeability to movement [10] | Applicable in data-poor contexts; incorporates expert knowledge | Subjective; potentially inconsistent; expert bias | Inter-expert reliability assessment; field validation |

| Species Distribution Models | Statistical relationships between species occurrences and environmental variables [10] | Empirical basis; species-specific predictions | Limited by occurrence data quality; assumes correlation with movement | Independent movement data; genetic markers |

| Habitat Quality Assessment | Models based on habitat quality and sensitivity to human impacts [9] | Captures intra-category variability; ecosystem-based | May not directly reflect movement permeability; complex parameterization | Species occurrence data; movement tracking |

Experimental Protocols for Component Analysis

Habitat Quality-Based Resistance Surface Development

The habitat quality-based method for resistance surface construction integrates the inherent environmental value of landscape units with their sensitivity to anthropogenic stressors, providing an ecologically-grounded approach to modeling landscape permeability. The experimental protocol involves sequential analytical phases:

Phase 1: Habitat Quality Assessment

- Data Preparation: Compile land use/land cover data, threat data (e.g., urban areas, roads, agricultural land), and habitat type classification. Data should be formatted as raster layers with consistent resolution and spatial extent.

- Parameterization: Define habitat types and their sensitivity to each threat (0-1 scale, where 1 indicates high sensitivity). Specify threat weights, decay functions (linear or exponential), and maximum effective threat distances based on empirical literature or expert consultation.

- Model Execution: Implement the habitat quality module using the InVEST model or similar software, which calculates habitat quality score Qxj for pixel x in habitat type j using the equation: Qxj = Hj [1 - (Dxjz / (Dxjz + kz))] where Hj is habitat suitability, Dxj is total threat level, k is half-saturation constant, and z is scaling parameter [9].

- Output Transformation: Convert habitat quality scores (0-1) to resistance values (1-100) using inverse relationship (high quality = low resistance), ensuring linear or logarithmic transformation based on ecological justification.

Phase 2: Resistance Surface Application

- Corridor Modeling: Input the habitat quality-based resistance surface into Least-Cost Path or Circuit Theory models to identify connectivity pathways.

- Validation: Compare model outputs with field data on species movement, genetic connectivity, or independent expert evaluation of landscape permeability.

- Sensitivity Analysis: Test model robustness to variations in parameter values, particularly threat weights and sensitivity scores.

This protocol was applied in Changzhou, China, where it demonstrated superior performance compared to traditional expert scoring and entropy coefficient methods, producing corridors more aligned with existing natural vegetation patches and known wildlife movement areas [9].

Multi-Species Corridor Identification Protocol

Multi-species connectivity analysis addresses the limitation of single-species approaches by incorporating the varied habitat requirements and movement capabilities of multiple species, providing a more comprehensive conservation planning framework. The experimental protocol involves:

Phase 1: Species Selection and Data Collection

- Assemblage Selection: Identify a representative group of species (typically 8-15) spanning taxonomic groups (mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians) and with varying mobility levels, habitat specializations, and conservation status. In a Victoria, Australia study, researchers selected 12 species including mammals (brush-tailed phascogale, sugar glider), birds (buff-rumped thornbill, fuscous honeyeater), and reptiles (Bougainville's skink, jacky lizard) [10].

- Data Compilation: Gather species occurrence data from systematic surveys, museum collections, or citizen science databases. Collect environmental variables including land cover, topography, climate, and human modification indices.

Phase 2: Resistance Surface Development

- Expert-Based Resistance: Convene a panel of species experts (typically 5-15 participants) to score land cover categories for each species using a standardized resistance scale (e.g., 1-100, where 1=minimal resistance, 100=maximum resistance). Calculate mean resistance values for each land cover category per species.

- SDM-Based Resistance: Develop species distribution models using MaxEnt, Random Forests, or other appropriate algorithms. Convert habitat suitability predictions to resistance values using negative relationships (high suitability = low resistance).

- Surface Comparison: Statistically compare expert-based and SDM-based resistance surfaces using spatial correlation analysis and evaluate ecological plausibility.

Phase 3: Connectivity Modeling and Integration

- Individual Species Corridors: For each species and resistance surface type, model corridors using Least-Cost Path or Circuit Theory approaches between identified core habitat patches.

- Multi-Species Integration: Create composite connectivity maps by (1) averaging resistance surfaces across species, or (2) overlaying individual species corridor maps to identify areas important for multiple species.

- Performance Validation: Compare the performance of expert-based versus SDM-based approaches using independent movement data, genetic differentiation (FST), or expert evaluation. In the Victoria study, expert-based resistance surfaces produced pathways more strongly aligned with existing vegetation patches and riparian zones, suggesting greater practical utility for conservation planning [10].

Analytical Workflow Visualization

The methodological integration of ecological sources, corridors, and resistance surfaces follows a sequential analytical workflow with multiple decision points that influence the final ecological network configuration.

Successful implementation of ecological network analysis requires specialized software tools, data resources, and analytical frameworks. The following table summarizes essential resources for researchers conducting comparative analyses of ecological network components.

Table 4: Essential Research Resources for Ecological Network Analysis

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Frameworks | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Analysis Software | ArcGIS (Linkage Mapper toolbox) [8], FragStats [4], Guidos Toolbox (MSPA) | Landscape pattern analysis; corridor mapping; connectivity assessment | General ecological network construction; landscape metrics calculation |

| Connectivity Modeling | Circuitscape [8], Conefor [4], Least-Cost Path algorithms [10] | Circuit theory implementation; connectivity indices; corridor identification | Pinch point analysis; importance assessment; network connectivity quantification |

| Habitat Assessment | InVEST Habitat Quality module [9], RSEI calculation scripts | Habitat quality modeling; ecological source identification | Resistance surface development; priority area delineation |

| Data Resources | Land use/land cover datasets, Remote sensing data (Landsat, Sentinel), Species occurrence databases | Base mapping; habitat distribution; model validation | All analysis phases; model parameterization and testing |

| Statistical Analysis | R packages (gdistance, SDMTools), MaxEnt | Resistance surface calculation; species distribution modeling | Statistical modeling; resistance surface development; model comparison |

Comparative analysis of methodologies for ecological sources, corridors, and resistance surfaces reveals significant trade-offs between ecological precision, computational requirements, and practical implementation. The emerging consensus favors integrated approaches that combine structural and functional assessments for ecological source identification, multi-species frameworks for corridor design, and habitat quality-based methods for resistance surface development. Future methodological advancements should focus on improving the integration of temporal dynamics, scaling relationships between landscape patterns and ecological processes, and strengthening validation protocols using empirical movement data. The selection of specific methodological approaches should be guided by conservation objectives, data availability, and the spatial-temporal scale of analysis, with composite methods generally providing more robust foundations for conservation decision-making in complex, fragmented landscapes.

The Ecological Network Dynamics Framework (ENDF) represents a unified approach for analyzing the complex interplay between the structural properties of ecological networks and their functional dynamics in response to environmental change. This framework stresses that the interplay between species interaction networks and the spatial layout of habitat patches is key to identifying which network properties and trade-offs among them are needed to maintain species interactions in dynamic landscapes [12]. The ENDF integrates concepts from dynamical systems theory, ecological psychology, and complex systems science to investigate relationships emerging between organisms and their environments [13]. As ecological networks vary in space and time as a function of environmental conditions and other factors, this framework provides essential analytical tools for conceptualizing, visualizing, and modeling these complex relationships [12]. The application of this framework spans fundamental ecological research, conservation planning, and sustainable ecosystem management, making it particularly valuable for researchers and scientists investigating complex biological systems.

Theoretical Foundations of the Ecological Network Dynamics Framework

The Ecological Network Dynamics Framework is supported by three theoretical pillars that integrate structure and function:

Constraint-Driven Emergence: Movement coordination patterns and network structures emerge from dynamically functional relationships between sets of interacting constraints, including the environment, the task, and the resources of a performer [13]. This pillar emphasizes that the performer-environment coupling constitutes the smallest unit of analysis for investigating ecological performance and expertise, requiring examination on an ecological scale where eco-physical variables indicate relationships between organisms and their surroundings.

Complex Adaptive Systems: The performer-environment coupling functions as a complex adaptive system exhibiting non-linear and non-proportional properties [13]. These systems demonstrate multi-stability, where multiple stable performance solutions can emerge depending on action opportunities offered by the environment and perceived by organisms according to their capabilities. This degeneracy in perceptual-motor systems allows behavioral structure to vary without compromising functional task achievement.

Perception-Action Coupling: Coordination variability emerges from continuous co-regulation of perceptual and motor processes through information pick-up for affordances that both solicit and constrain behaviors [13]. These affordances are both objective and subjective to each performer since they are ecological properties of the environment picked up relative to an individual's own action capabilities, being both body-scaled and action-scaled.

Comparative Analysis of Ecological Network Methodologies

Table 1: Comparison of Ecological Network Analysis Methods

| Method Type | Network Focus | Key Metrics | Temporal Dimension | Data Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spatio-temporal Networks [12] | Species interactions across habitat patches | Node/link persistence, Weight dynamics | Multiple time periods | Species distribution data, Habitat maps, Movement data |

| Multilayer Networks [12] | Multiple interaction types or locations | Interlayer connectivity, Cross-layer dependencies | Implicit through layers | Multi-taxa interactions, Environmental variables |

| Nonlinear Time Series Analysis [14] | Causality in species interactions | Cross-map skill, S-map coefficients | Continuous | High-frequency time series, Quantitative eDNA |

| Structural Network Analysis [3] | Topological properties | Connectance, Modularity, Centrality | Static snapshot | Species interaction records, Food web data |

Table 2: Quantitative Metrics for Network Stability Assessment

| Metric Category | Specific Metrics | Ecological Interpretation | Theoretical Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complexity Measures [3] | Species richness (S), Connectance (C), Link density | Network complexity, Interaction diversity | S > 0, 0 < C < 1 |

| Stability Indicators [3] | Persistence, Robustness, Qualitative stability | Resistance to perturbation, Recovery capacity | 0 to 1 (probability) |

| Structural Metrics [15] | Modularity, Strongly Connected Components (SCCs) | Compartmentalization, Interaction redundancy | -1 to 1 (modularity) |

| Dynamic Properties [12] | Node/link transience, Weight variability | Network rewiring, Interaction strength changes | Situation-dependent |

The comparison reveals that methodological approaches span from static structural analyses to dynamic, process-oriented frameworks. Spatio-temporal networks [12] excel in capturing how nodes and links change position and weight over time, making them particularly valuable for studying ecological responses to environmental change. In contrast, nonlinear time series analysis [14] enables the detection of causal relationships in complex systems through high-frequency monitoring, providing superior capacity for predicting system dynamics. The multilayer network approach [12] offers unique advantages for modeling multiple interaction types simultaneously, though with increased data requirements.

Research indicates that structural metrics alone provide limited insight into ecological dynamics without complementary functional analysis [3] [15]. Studies have demonstrated significant negative correlations between modularity and robustness in empirical food webs [15], suggesting that topological characteristics directly influence system stability. Furthermore, the size of strongly connected components (SCCs) shows positive correlation with persistence in replacement networks [15], highlighting the importance of specific structural configurations for maintaining ecological functions.

Experimental Protocols for Network Dynamics Analysis

Protocol for eDNA-Based Ecological Network Reconstruction

The integration of environmental DNA (eDNA) metabarcoding with nonlinear time series analysis represents a cutting-edge methodology for reconstructing ecological networks under field conditions [14]:

Field Monitoring Design: Establish replicated monitoring plots (e.g., 5 rice plots as in Ushio et al.'s study) with daily measurements of target species performance metrics (e.g., rice growth rate in cm/day) throughout the study period (e.g., 122 consecutive days) [14].

Quantitative eDNA Sampling: Implement quantitative eDNA metabarcoding with internal spike-in DNAs to enable accurate quantification of ecological community members. This approach allows detection of 1000+ species including microbes and macrobes simultaneously [14].

Time Series Causality Analysis: Apply empirical dynamic modeling (EDM) techniques, specifically convergent cross-mapping (CCM), to detect causal relationships between species abundances and ecological performance metrics. This nonlinear approach can identify 50+ potentially influential species from extensive time series data [14].

Field Validation: Conduct manipulative experiments targeting species identified as influential through time series analysis. For example, add Globisporangium nunn or remove Chironomus kiiensis from experimental plots, then measure responses in growth rates and gene expression patterns to validate detected interactions [14].

Protocol for Spatial Ecological Network Analysis

The construction of Ecological Security Patterns (ESPs) integrates spatial analysis with network theory for landscape-scale conservation planning [16]:

Ecosystem Service Assessment: Quantify four key ecosystem services (provisioning, regulating, cultural, and supporting) using spatial modeling techniques, including the InVEST software platform [17] [16].

Morphological Spatial Pattern Analysis (MSPA): Identify core habitat patches and structural connectors using satellite imagery and land cover classification to define potential ecological sources [16].

Resistance Surface Modeling: Develop landscape resistance maps incorporating novel factors specific to the study region, such as snow cover days in cold regions [16].

Circuit Theory Application: Model ecological corridors using Circuit Theory to identify prioritized connectivity pathways, then quantify ecological risk using landscape indices and evaluate economic efficiency with genetic algorithms to optimize corridor width and placement [16].

Visualization of Ecological Network Dynamics

Framework Integration Diagram

Experimental Workflow for Network Dynamics Research

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Ecological Network Analysis

| Tool Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Collection Technologies | Quantitative eDNA metabarcoding [14] | Comprehensive species detection | Field monitoring of diverse taxa |

| High-throughput sequencing [18] | Rapid processing of interaction data | Microbial and microbiome networks | |

| Remote sensing/GIS [16] | Spatial pattern analysis | Landscape-scale network mapping | |

| Analytical Software Platforms | InVEST [17] | Ecosystem service assessment | Spatial network optimization |

| ARIES [17] | Artificial intelligence for ES | Rapid network modeling | |

| R/Network Analysis Packages [19] | Metric calculation and visualization | Structural network characterization | |

| Theoretical Frameworks | Network Theory [12] [3] | Structural analysis | Predicting stability and dynamics |

| Complex Systems Theory [13] | Dynamics modeling | Understanding emergent properties | |

| Nonlinear Time Series Analysis [14] | Causal inference | Detecting species interactions |

Applications in Conservation and Ecosystem Management

The Ecological Network Dynamics Framework provides critical insights for environmental management and conservation strategy development. Research demonstrates that ecological security patterns can be optimized using a novel connectivity-ecological risk-economic efficiency (CRE) framework that integrates ecosystem services, morphological spatial pattern analysis, and climate-specific resistance factors like snow cover days [16]. This approach has revealed that supplementing priority ecological corridors significantly improves network robustness, with corridor width optimization (approximately 630-635 meters in studied systems) achieving measurable risk and cost reductions [16].

In agricultural systems, the framework enables identification of influential organisms affecting crop performance through integrated monitoring and nonlinear time series analysis. The detection of previously overlooked species such as Globisporangium nunn (Oomycetes) and Chironomus kiiensis (midge) as significantly influencing rice growth demonstrates the power of this approach for identifying critical interactions in complex food webs [14]. This application has particular relevance for sustainable agriculture development seeking to harness ecological complexity rather than simplify it.

The framework also advances conservation planning by highlighting how network topologies constrain ecological dynamics. Studies of strongly connected components (SCCs) in food webs reveal that their size positively correlates with persistence, providing guidance for prioritizing conservation interventions [15]. Similarly, the observed negative correlation between modularity and robustness offers critical insights for designing resilient protected area networks that maintain ecosystem functions despite ongoing environmental changes [3] [15].

The Ecological Network Dynamics Framework represents a powerful integrative approach for analyzing the complex relationship between ecological structure and function across spatial and temporal scales. By combining theoretical foundations from complex systems science with advanced empirical methodologies and analytical techniques, this framework enables researchers to move beyond static structural analyses to dynamic, process-oriented understanding of ecological networks. The comparative analysis presented here reveals that methodological integration—particularly combining spatio-temporal network modeling with nonlinear time series analysis and empirical validation—provides the most robust approach for predicting ecological responses to environmental change. As global challenges of biodiversity loss and ecosystem degradation intensify, further development and application of this framework will be essential for designing effective conservation strategies and sustainable ecosystem management practices.

Spatio-temporal network analysis provides a powerful framework for studying the evolution of complex systems across both time and space. In ecology, this approach is fundamental for understanding how species interactions change due to environmental pressures, habitat fragmentation, and climate change. Temporal dynamics in ecological networks encompass changes in network topology and the flow of resources or energy through the network over time [20]. Static network analyses, which assume fixed topologies and persistent interactions, often misrepresent real biological systems where interactions dynamically change, potentially leading to inferential problems [21]. The integration of spatial components allows researchers to model how these temporal changes manifest across geographical landscapes, creating a more comprehensive understanding of ecological processes.

The study of spatio-temporal dynamics extends beyond ecology into biomedical research, where network approaches model disease spread, protein interactions, and drug delivery systems. For instance, in cancer research, image-based spatio-temporal computational models of solid tumors have been developed to simulate interstitial fluid flow and solute transport, incorporating heterogeneous microvasculature for angiogenesis instead of synthetic mathematical modeling [22]. Such models employ Convection-Diffusion-Reaction (CDR) equations to simulate the binding and uptake of drugs by tumor cells with high accuracy, demonstrating how spatial relationships and temporal processes jointly influence treatment outcomes.

Comparative Analysis of Methodological Approaches

Statistical Model-Based Frameworks

Model-based clustering of time-evolving networks represents a sophisticated statistical approach for detecting groups of nodes with similar connectivity patterns over time. This framework utilizes discrete time exponential-family random graph models (TERGMs) to simultaneously model network evolution and detect group structures [23]. The approach is particularly valuable for identifying clusters based on specific network features such as stability, which varies across different node types. The mathematical foundation of one-step transition probability under first-order Markov assumption is expressed as:

[ Pr(Yt = yt | y{t-1}) = \exp{\theta^\top g(yt, y{t-1}) - \psi(\theta, y{t-1})} ]

Where (Yt) represents the network at time (t), (\theta) is a vector of network parameters, (g(yt, y_{t-1})) is a vector of sufficient statistics, and (\psi) ensures proper probability normalization [23]. This formulation allows researchers to incorporate domain-specific knowledge through carefully chosen statistics that capture interesting temporal features such as stability, reciprocity, or degree persistence.

Table 1: Comparison of Model-Based Clustering Approaches for Temporal Networks

| Method | Theoretical Foundation | Temporal Handling | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model-based clustering with TERGM | Exponential-family random graph models | Discrete time, first-order Markov | Simultaneously models network evolution and group structure; incorporates meaningful features | Computationally intensive for large networks |

| Stochastic Blockmodel (SBM) | Stochastic equivalence | Multiple variants (static, mixed membership, degree-corrected) | Identifies groups with more edges within than between groups | Assumes static community structure in basic form |

| Molecular Ecological Networks (MENs) | Random Matrix Theory | Correlation across time series | Automatic threshold detection; robust to noise | Requires sufficient temporal replication |

Algorithmic and Computational Approaches

Dynamic community detection algorithms represent another major approach for understanding network evolution. A recent comparative study evaluated six state-of-the-art dynamic community detection methods, identifying significant variation in their performance and scalability [24]. The study found that vertex-centric local optimization methods, particularly those based on permanence, achieved computational efficiency comparable to classical modularity-based methods while avoiding arbitrary tie-breaking scenarios common in global optimization approaches.

The permanence metric, calculated as:

[ Perm(v) = \left[ \frac{I(v)}{E{max}(v)} \times \frac{1}{d(v)} \right] - \left[ 1 - C{in} \right] ]

where (I(v)) represents internal connections, (E{max}(v)) is maximum connections to a single external community, (d(v)) is the degree of vertex (v), and (C{in}) is internal clustering coefficient, enables efficient parallel computation without significant parallel overhead [24]. This local computability facilitated the development of DyComPar, a shared-memory parallel algorithm that demonstrates between 4 and 18 fold speed-up on a multi-core machine with 20 threads across various real-world and synthetic networks.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Dynamic Community Detection Algorithms

| Algorithm | Theoretical Basis | Scalability | Quality Metrics | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DyComPar | Permanence optimization | High (parallelizable) | Modularity, conductance, temporal smoothness | Large-scale dynamic networks |

| TERGM-based clustering | Exponential random graphs | Moderate | Likelihood, classification accuracy | Feature-based temporal clustering |

| RMT-based MENs | Random Matrix Theory | Moderate to high | Modularity, scale-freeness, robustness | Microbial ecological networks |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Long-Term Ecological Network Monitoring

Understanding temporal dynamics in ecological networks requires meticulous long-term data collection. A seminal 12-year study of flower-visitation networks between butterflies and nectar plants established a robust protocol for temporal network analysis [25]. Researchers conducted observations at El Puig, an open Mediterranean shrubland in NE Spain, with standardized weekly samplings (30 per year) from March to September over 12 consecutive years (1996-2007). The methodology involved:

- Transect Sampling: All butterflies within 2.5 meters on each side of a 2,029-meter long transect and 5 meters in front of the recorder were counted.

- Interaction Recording: Researchers scored all interactions between flower-visiting butterfly species and their nectar plants, including frequency measurements.

- Standardization: A fixed observation protocol throughout all 12 years minimized sampling variability, with time investment varying seasonally (1 hour weekly early in season, 2-3 hours weekly in mid-season July).

- Data Structuring: All data were arranged in annual, bipartite plant-butterfly interaction matrices for longitudinal analysis.

This comprehensive approach allowed researchers to quantify colonization and extinction probabilities for species and links, calculated as (e = \frac{\text{no. extinctions during 12 yrs}}{\text{no. extinctions during 12 yrs} + \text{no. survivals during 12 yrs}}) and (c = \frac{\text{no. colonizations during 12 yrs}}{\text{no. colonizations during 12 yrs} + \text{no. survivals during 12 yrs}}) respectively, with mean annual turnover rate defined as (t = \frac{e + c}{2}) [25].

Molecular Ecological Network Analysis

The Molecular Ecological Network Analysis Pipeline (MENAP) provides a standardized framework for constructing and analyzing ecological association networks from high-throughput metagenomic data [26]. The process consists of two main phases:

Phase 1: Network Construction

- Data Collection: Gathering high-throughput sequencing data (e.g., 16S rRNA gene pyrosequencing)

- Data Transformation: Standardizing abundance data into relative abundance

- Similarity Matrix Calculation: Computing pair-wise similarity matrices between operational taxonomic units (OTUs)

- Adjacency Matrix Determination: Using Random Matrix Theory (RMT) to automatically identify optimal thresholds for network construction

Phase 2: Network Analysis

- Topology Characterization: Calculating network properties including scale-freeness, small-worldness, modularity, and hierarchy

- Module Detection: Identifying groups of OTUs that are highly connected among themselves but have fewer connections to OTUs outside the group

- Eigengene Analysis: Representing module profiles through eigengenes

- Environmental Association: Establishing relationships between network properties and environmental characteristics

The robustness of MENs to noise has been experimentally validated by adding different levels (1% to 100% of original standard deviation) of Gaussian noise to datasets and examining network preservation [26]. Results demonstrated that with less than 40% noise added, roughly 90% of original OTUs remained detected in perturbed networks, indicating strong methodological robustness.

Deep Learning for Spatio-Temporal Forecasting

CASTNet (Community-Attentive Spatio-Temporal Networks) represents a novel deep learning approach for forecasting dynamic processes across networked systems [27]. Originally developed for opioid overdose forecasting using real-time crime dynamics, the methodology can be adapted for ecological applications. The experimental protocol includes:

- Multi-head Attentional Networks: Learning different representation subspaces of features through attention mechanisms

- Community-Attentive Architecture: Allowing predictions for a given location to be optimized by mixtures of region groups (communities)

- Interpretability Features: Identifying which features from which communities contribute most to predictions

- Cross-domain Validation: Testing models on multiple real-world datasets to ensure generalizability

This approach captures both spatial dependencies (through community structures) and temporal dynamics (through sequential learning), providing a powerful framework for predicting ecological phenomena across spatial and temporal dimensions.

Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Spatio-Temporal Network Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| MENAP (Molecular Ecological Network Analysis Pipeline) | Software Pipeline | RMT-based network construction and analysis | Microbial ecology, metagenomics studies |

| ANINHADO | Software Package | Calculate nestedness (NODF index) in bipartite networks | Plant-pollinator, host-parasite networks |

| DyComPar | Parallel Algorithm | Dynamic community detection using permanence | Large-scale temporal network analysis |

| uSonic-3 Scientific Anemometer | Field Instrument | 3D wind speed measurement for eddy covariance | Atmospheric-biospheric exchange studies |

| LI-7200RS Gas Analyzer | Field Instrument | CO₂ and H₂O mole fraction measurements | Carbon flux studies in aquatic and terrestrial systems |

| Picarro G1301-f Gas Analyzer | Field Instrument | CH₄ and H₂O mole fraction measurements | Methane flux monitoring in ecosystems |

| Random Matrix Theory (RMT) | Mathematical Framework | Automatic threshold detection for network construction | Cellular and ecological network inference |

Significant Findings and Empirical Patterns

Temporal Stability and Local Instability in Ecological Networks

The long-term butterfly-plant interaction study revealed a fundamental paradox in ecological networks: global stability coexists with strong local dynamics [25]. While global network properties (species numbers, links, connectance) remained temporally stable, most species and links showed strong temporal dynamics. Specifically, species of butterflies and plants varied bimodally in temporal persistence:

- Sporadic Species: Present only 1-2 years (16% of butterflies, 61% of plants)

- Stable Species: Present 11-12 years (60% of butterflies, 21% of plants)

Links demonstrated even stronger dynamics, with 68% being sporadic (lasting only 1-2 years) and only 2% stable (lasting 11-12 years). This indicates that network stability is maintained through compensatory mechanisms rather than constancy of individual components.

Specialist-Generalist Dynamics in Network Evolution

The topological analysis of temporal networks revealed distinct dynamics between specialists and generalists [25]. In the butterfly-plant network, species were categorized as specialists (linkage level L ≤ 2) or generalists (L > 2), with these groups almost equally represented. However, 70% of all links connected generalists, while only 2% connected specialists. Crucially, the turnover of links followed different mechanisms:

- Specialist Link Turnover: Driven primarily by species turnover

- Generalist Link Turnover: Occurred mainly through rewiring (reshuffling existing interactions)

This finding demonstrates how different ecological strategies result in distinct temporal dynamics within the same network.

Microbial Network Responses to Environmental Change

The application of MENs to microbial communities under experimental warming revealed systematic changes in network architecture [26]. Analysis of 16S rRNA gene pyrosequencing data from grassland soils with ambient and +2°C warming treatments showed that:

- Network Size: Warming increased network nodes from 152 to 177 and edges from 263 to 279

- Topological Properties: Both warming and unwarming networks exhibited scale-free, small-world, and modular properties

- Key Drivers: Temperature and soil pH were identified as critical factors determining network interactions

These findings demonstrate that microbial networks undergo predictable structural changes in response to environmental perturbations, with implications for ecosystem stability and function under climate change scenarios.

Implications for Ecological Research and Conservation

The comparative analysis of spatio-temporal network methods reveals several important implications for ecological research and conservation practice. First, the choice of analytical approach should align with specific research questions and data characteristics. Model-based clustering with TERGMs excels when researchers have hypotheses about specific network features driving community assembly [23]. In contrast, algorithmic approaches like DyComPar offer computational advantages for large-scale networks where detection of community evolution is the primary goal [24].

Second, the consistent finding of local instability within globally stable networks [25] suggests that conservation strategies should focus on maintaining functional redundancy and response diversity rather than preserving specific species interactions. This perspective acknowledges the dynamic nature of ecological networks while seeking to preserve their overall structure and function.

Finally, the integration of spatial and temporal dimensions in network analysis enables more accurate predictions of ecological responses to environmental change. Methods like CASTNet [27], though developed in other domains, offer promising approaches for forecasting ecological dynamics across landscapes under changing climatic conditions. As these methodologies continue to mature, they will enhance our ability to understand, predict, and manage complex ecological systems in an increasingly dynamic world.

Table of Contents

- Introduction to Ecological Network Analysis

- Comparative Analysis of Key Network Properties

- Experimental Protocols for Network Analysis

- Visualizing Network Properties and Workflows

- The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

Ecological networks are complex systems that map the interactions, such as predation, mutualism, and competition, between different species within an ecosystem [28]. The analysis of these networks provides a powerful, interdisciplinary framework for understanding the structure, behavior, and dynamics of ecological systems, revealing patterns and relationships that are not apparent when examining individual species in isolation [29]. By representing ecosystems as networks—where species are nodes and their interactions are edges—researchers can quantify properties that determine stability, resilience, and function [29] [28]. For researchers and drug development professionals, particularly in fields like biodiscovery and microbiome studies, these methods are invaluable for identifying key species, predicting responses to perturbations, and understanding the complex interplay within microbial communities that can be harnessed for therapeutic applications [28] [18].

This guide focuses on three foundational categories of network properties. Connectivity describes the broad-scale patterns of interaction, while circuitry delves into the specific pathways that facilitate the flow of energy or information. Finally, node and link importance identifies the critical elements whose presence or absence disproportionately affects the entire network's function and stability [29].

Comparative Analysis of Key Network Properties

The analytical power of network analysis comes from quantitative metrics that describe a network's architecture. The table below summarizes the purpose, application, and experimental basis for key properties related to connectivity, circuitry, and importance.

Table 1: Key Properties for Comparative Ecological Network Analysis

| Network Property | Purpose & Definition | Relevance in Ecological Networks | Experimental Basis & Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Connectivity | |||

| Node Degree | Measures the number of direct connections a node (e.g., a species) has [29]. | Identifies generalist species (high degree) versus specialist species (low degree). High network average degree may increase robustness but also facilitate cascading failures [29]. | Derived from species interaction data obtained via high-throughput sequencing (e.g., meta-barcoding for trophic interactions) [18]. |

| Path Length | The number of steps required to connect two nodes in the network [29]. | Short average path length indicates rapid energy flow and potential for swift propagation of disturbances (e.g., pollutant effects) through the ecosystem [29]. | Calculated from the full network graph. Inferred from co-occurrence networks built from microbial community sequencing data [28]. |

| Clustering Coefficient | Measures the tendency of a node's neighbors to also be connected to each other, forming tightly-knit groups [29]. | High clustering suggests modular community structure and functional redundancy, which can buffer the network against species loss [29]. | Calculated from the network graph. Used in trait-based approaches to understand community assembly [18]. |

| Circuitry | |||

| Modularity | Quantifies the extent to which a network is subdivided into distinct, non-overlapping modules (sub-communities) [29]. | High modularity is a key indicator of a system's ability to compartmentalize shocks, preventing a local disturbance from spreading globally [29]. | Detected computationally from the network using community detection algorithms [29]. Observed in phage-bacteria networks [28]. |

| Mesh Analysis | A method from circuit theory applied to identify all independent closed loops (meshes) within a network [30]. | Useful for modeling nutrient or energy cycles (e.g., nitrogen cycle) and identifying feedback loops that contribute to ecosystem stability or instability [30]. | The network is mapped as a topological graph where branches represent flows (e.g., energy) and nodes represent states (e.g., species pools) [30]. |

| Node/Link Importance | |||

| Centrality Measures | A family of metrics (e.g., Betweenness, Eigenvector) that identify the most important or influential nodes in a network [29]. | Identifies keystone species. High betweenness centrality species act as critical bridges; high eigenvector centrality species are connected to other well-connected species [29] [18]. | Calculated from the network structure. Machine learning algorithms can predict keystone species from network topology and trait data [18]. |

| Link | A measure of the importance of a specific interaction (edge) for network cohesion, often analogous to edge betweenness [29]. | Identifies critical interactions whose removal could fragment the network or collapse key functions, such as a specific pollination or predation link [29]. | Determined by simulating the removal of individual links and measuring the resulting impact on network diameter or cohesion. |

Experimental Protocols for Network Analysis

Robust ecological network analysis relies on standardized methodologies for data collection, network construction, and computational interrogation. The following protocols detail the core workflows.

Protocol A: Constructing an Interaction Network from High-Throughput Sequencing Data

1. Sample Collection & Metagenomic Sequencing:

- Procedure: Collect environmental samples (e.g., soil, water, gut content) from multiple time points or locations. Extract total DNA/RNA. Prepare sequencing libraries targeting universal phylogenetic markers (e.g., 16S rRNA for bacteria) or entire genomes via shotgun metagenomics. Sequence using a high-throughput platform (e.g., Illumina) [18].

- Purpose: To obtain a comprehensive profile of the species (taxa) present and their relative abundances in the community.

2. Bioinformatics & Interaction Inference:

- Procedure: Process raw sequences using bioinformatics pipelines (e.g., QIIME 2, mothur) for quality filtering, denoising, and amplicon sequence variant (ASV) calling. For shotgun data, perform taxonomic binning and profiling. Construct an abundance table (samples x taxa).

- Network Inference: Use statistical tools (e.g., SparCC, SPIEC-EASI) to calculate robust correlation measures (e.g., Spearman, Pearson) between the abundance profiles of all taxon pairs. These correlations are used as a proxy for ecological interactions [28] [18].

- Purpose: To transform abundance data into a matrix of potential species interactions.

3. Network Construction & Pruning:

- Procedure: Create a network graph where nodes represent taxa and edges represent significant correlations. Prune the network by applying a correlation coefficient threshold (e.g., |r| > 0.6) and a statistical significance threshold (e.g., p-value < 0.01, adjusted for multiple comparisons) to remove spurious links [18].

- Purpose: To generate a computationally tractable and biologically relevant network model for analysis.

Protocol B: Interrogating Network Robustness via Node Removal Simulation

1. Baseline Metric Calculation:

- Procedure: Calculate global network metrics for the intact, pruned network from Protocol A. Key metrics include Connectivity (e.g., graph density), Circuitry (e.g., modularity), and global efficiency [29].

- Purpose: To establish a baseline for network structure and function before perturbation.

2. Targeted & Random Node Removal:

- Procedure: Simulate two removal scenarios using a computational script (e.g., in R or Python):

- Targeted Removal: Iteratively remove nodes in descending order of a specific importance metric (e.g., highest to lowest degree or betweenness centrality).

- Random Removal: Iteratively remove nodes selected at random. After each removal, recalculate the global network metrics from Step 1 [29].

- Purpose: To compare the vulnerability of the network to the loss of key species versus random species loss.

3. Resilience Quantification:

- Procedure: Plot the value of a key metric (e.g., global efficiency or connectedness) against the proportion of nodes removed. The robustness is often quantified as the area under this curve. A network that maintains higher functionality during targeted removal is considered more resilient [29].

- Purpose: To objectively compare the resilience of different ecological networks or the importance of different centrality measures.

Visualizing Network Properties and Workflows

Visualizations are crucial for understanding complex network relationships and analytical workflows. The following diagrams, created using the specified color palette, illustrate core concepts.

Network Architecture Comparison

Network Construction Workflow

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

Conducting ecological network analysis requires a combination of wet-lab, computational, and analytical resources. The following table details key solutions and their functions.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Ecological Network Analysis

| Category | Item / Solution | Primary Function in Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Wet-Lab & Data Collection | High-Throughput Sequencer (e.g., Illumina NovaSeq) | Generates the raw DNA sequence data used to determine species presence and abundance in a sample [18]. |

| DNA/RNA Extraction Kits (e.g., Qiagen DNeasy PowerSoil) | Standardizes the isolation of high-quality genetic material from complex environmental samples for downstream sequencing [18]. | |

| Universal Primer Sets (e.g., 16S rRNA V4 region) | Allows for the amplification of a conserved genetic region to profile specific taxonomic groups (e.g., bacteria) across all samples [18]. | |

| Bioinformatics & Computation | Interaction Inference Algorithms (e.g., SparCC, MENAP) | Statistical software packages designed to infer robust species interaction networks from abundance correlation data, correcting for compositionality [18]. |

| Network Analysis Suites (e.g., Igraph, Cytoscape) | Software libraries or platforms used to construct, visualize, and calculate key network metrics (e.g., centrality, modularity) from the interaction matrix [29]. | |

| Programming Environments (e.g., R with 'vegan', Python with 'NetworkX') | Flexible computational environments that integrate data processing, statistical analysis, and custom network analysis workflows [29] [18]. |

Methodological Approaches and Practical Implementation Frameworks

Ecological connectivity is a global priority for preserving biodiversity and ecosystem function, and circuit theory has emerged as a transformative approach for modeling ecological flows across heterogeneous landscapes [31]. The foundational work of the late Brad McRae, who introduced the concept of "isolation by resistance" in 2006, established that animals, plants, and genes follow the path of least resistance—much like electrical current—when moving across landscapes to find resources and suitable habitats [32] [31]. This breakthrough recognized that ecological connectivity occurs via all possible pathways between habitat patches, not just along a single optimal route, providing a more robust theoretical framework for understanding gene flow and organism movement.

Circuitscape implements these circuit theory principles through open-source software that borrows algorithms from electronic circuit theory to predict connectivity in heterogeneous landscapes [33]. By representing landscapes as circuit boards where each pixel is a resistor, Circuitscape calculates patterns of ecological flow using two primary metrics: current density, which estimates net movement probabilities of random walkers through specific locations, and effective resistance, which provides a pairwise measure of isolation between populations or sites [31]. This approach has fundamentally advanced the field of landscape genetics and connectivity conservation by moving beyond the limitations of earlier methods like least-cost path analysis, which assumed perfect landscape knowledge and identified only single optimal routes [31].

Circuitscape in Comparative Ecological Network Analysis

Methodological Comparison of Connectivity Approaches

Ecological network analysis employs multiple methodological approaches, each with distinct strengths and limitations. The table below provides a systematic comparison of Circuitscape against other prominent connectivity modeling techniques:

Table 1: Comparative analysis of ecological connectivity modeling methods

| Method | Theoretical Foundation | Key Outputs | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Circuitscape | Electronic circuit theory | Current density maps, effective resistance, pinch points | Models flow across all possible paths; identifies connectivity barriers and bottlenecks; explains genetic patterns 50-200% better than conventional approaches [31] | Assumes random movement; computationally intensive for very large landscapes |

| Least-Cost Path | Geographic cost-distance analysis | Single optimal corridor, cumulative resistance | Simple implementation; intuitive results; performs well for species with established routes [34] | Oversimplifies movement to single path; misses alternative routes and pinch points |

| Isolation by Distance | Population genetics | Genetic differentiation vs. geographic distance | Simple null model; requires only geographic coordinates | Ignores landscape heterogeneity; poor predictive power when resistance varies |

| Omniscape | Circuit theory with moving window | Omnidirectional connectivity, source-sink dynamics | "Coreless" approach; identifies both sources and sinks of connectivity [33] | Requires significant computational resources; complex parameterization |

Circuitscape's fundamental advantage lies in its ability to model multiple movement pathways simultaneously, which closely approximates how organisms actually explore landscapes during dispersal or in response to environmental changes [31]. This multi-path approach proves particularly valuable for identifying critical pinch points—narrow, constricted areas where connectivity is vulnerable to disruption—as demonstrated in tiger corridor planning in India, where Circuitscape revealed specific areas most crucial for maintaining network connectivity [34].

Experimental Performance Validation

Rigorous field validation studies have quantified Circuitscape's performance relative to alternative methods across multiple species and landscapes. A comprehensive study examining 459 papers that cited McRae et al. (2008) or the Circuitscape user guide revealed that 277 directly used the software, demonstrating its rapid adoption across diverse ecological contexts [31]. Experimental comparisons with GPS-collared animals provided particularly insightful validations:

Table 2: Experimental validation of Circuitscape performance across species

| Study System | Method Comparison | Performance Outcome | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wolverine dispersal, Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem [34] | Circuitscape vs. Least-cost path | Circuitscape outperformed least-cost paths for predicting wolverine dispersal | Dispersing juveniles explore landscapes randomly rather than following optimal paths |

| Elk movement, Western US [34] | Circuitscape vs. Least-cost path | Least-cost paths slightly outperformed Circuitscape | Elk follow established routes with better landscape knowledge |

| African wild dogs and cheetahs, South Africa [34] | Circuitscape predictions vs. Empirical movement data | Successfully predicted actual movement corridors | Validated circuit theory's applicability for carnivore conservation planning |

| Vehicle collisions with roe deer, France [34] | Circuitscape vs. Other connectivity models | Circuit theory outperformed other models for predicting collision locations | Demonstrated utility for mitigating road impacts on wildlife |

McClure et al. (2016) demonstrated that Circuitscape's performance varies ecologically based on species movement behavior—it excelled for predicting wolverine dispersal but slightly underperformed for elk movement prediction [34]. This distinction highlights how biological context should guide method selection, with Circuitscape particularly effective for modeling exploratory movements where organisms lack perfect landscape knowledge.

Experimental Protocols for Circuitscape Implementation

Standardized Workflow for Connectivity Analysis

Implementing Circuitscape for ecological network analysis follows a structured workflow with distinct methodological stages. The diagram below visualizes this standardized experimental protocol:

The experimental workflow begins with data preparation, requiring two primary inputs: habitat patches (representing source and destination areas for ecological flows) and a resistance surface (representing the landscape's permeability to movement, typically derived from habitat suitability models) [31]. Researchers then configure analysis parameters by designating specific habitat patches as voltage sources (origins of movement) and ground nodes (movement destinations), establishing the circuit complete with potential differences that drive current flow [32] [31].

Execution of Circuitscape computations generates two primary categories of outputs: current density maps visualizing predicted movement patterns across all possible pathways, and effective resistance values quantifying isolation between specific locations [31]. The model validation phase typically employs empirical genetic data (e.g., FST values) or animal movement tracking (e.g., GPS collar data) to assess prediction accuracy [31] [34]. Finally, results inform conservation applications, including corridor design, pinch point identification, and barrier mitigation [34].

Advanced Computational Implementation

Modern Circuitscape implementations leverage the Julia programming language for enhanced computational efficiency, enabling analyses of increasingly large and complex landscapes [33] [32]. The software ecosystem has expanded to include several specialized tools:

- Omniscape.jl: Implements a "coreless" approach by applying Circuitscape iteratively in a moving window to predict omni-directional connectivity [35]

- Circuitscape.jl: The core Julia package providing algorithms from circuit theory to predict connectivity in heterogeneous landscapes [35]

- CircuitscapeForArcGIS: An ArcToolbox that enables users to call Circuitscape directly from GIS environments [35]

This computational advancement has been crucial for large-scale applications, such as modeling climate-driven range shifts for nearly 3,000 species across the Western Hemisphere, which would be computationally prohibitive with earlier implementations [34].

The Researcher's Toolkit for Circuitscape Analysis

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of Circuitscape requires specific data inputs and analytical components that function as essential "research reagents" in connectivity analysis:

Table 3: Essential research reagents for Circuitscape ecological connectivity analysis

| Research Reagent | Function | Data Sources | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resistance Surface | Quantifies landscape permeability to movement [31] | Land cover data, remote sensing, habitat models | Can be derived from resource selection functions or expert opinion |

| Habitat Patches | Defines source and destination areas for connectivity [31] | Protected areas, species occurrence data, habitat models | Size and quality thresholds affect connectivity predictions |

| Genetic Data | Validates connectivity predictions [31] | Microsatellite analysis, SNP genotyping | FST values measure population differentiation; individual-based analyses possible |

| Movement Data | Ground-truths predicted corridors [34] | GPS tracking, telemetry, camera traps | Particularly valuable for assessing model performance across species |

| Climate Projections | Models future connectivity needs [34] | Downscaled GCMs, species distribution models | Enables climate resilience planning for conservation networks |

The resistance surface serves as the foundational reagent, representing landscape permeability where conductive areas (low resistance) facilitate movement while resistive areas (high resistance) impede it [31]. These surfaces are typically developed through expert consultation, empirical habitat modeling, or genetic algorithms that optimize resistance values to match observed genetic or movement patterns [31].

Hybrid Methodological Approaches