Bridging the Scale: A Comprehensive Framework for Assessing Accuracy Between Remote Sensing and Ground-Based Ecological Data

This article provides a systematic guide for researchers and scientists on the principles and practices of assessing the accuracy of remote sensing data against ground-based ecological measurements.

Bridging the Scale: A Comprehensive Framework for Assessing Accuracy Between Remote Sensing and Ground-Based Ecological Data

Abstract

This article provides a systematic guide for researchers and scientists on the principles and practices of assessing the accuracy of remote sensing data against ground-based ecological measurements. It covers the foundational relationship between satellite/airborne data and field observations, explores methodological frameworks for integration and comparison, addresses common challenges and optimization techniques, and details rigorous validation and comparative analysis procedures. By synthesizing current methodologies and emerging trends, this resource aims to enhance the reliability and application of remote sensing in ecological monitoring, environmental assessment, and climate change research.

The Core Relationship: Understanding Remote Sensing and Ground-Based Data Synergy

In ecological research, accurately assessing environmental conditions requires a multi-platform approach. No single data source provides a complete picture; instead, researchers must understand the strengths and limitations of various collection methods. This guide objectively compares four fundamental data acquisition platforms—satellite, airborne, Unoccupied Aerial Systems (UAS), and in-situ methods—within the context of assessing accuracy in ecological remote sensing. By examining their technical specifications, applications, and experimental validations, researchers can make informed decisions for integrating these technologies into robust ecological study designs.

Remote sensing platforms operate at different spatial scales and resolutions, creating a complementary hierarchy of data collection capabilities. The integration of these platforms is essential for cross-scale inference of ecological patterns and processes, linking field-based measurements with broader landscape assessments [1] [2].

Table 1: Technical Comparison of Ecological Data Collection Platforms

| Platform | Spatial Resolution | Spatial Coverage | Temporal Resolution | Primary Data Types | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Satellite | 0.5–100 m | Continental to global | Days to weeks | Multispectral, hyperspectral, SAR, thermal | Broad-scale coverage, consistent long-term data, free access to some data (Landsat, Sentinel) | Fixed resolution, weather constraints (optical), lower detail for fine-scale processes |

| Airborne (Manned Aircraft) | 0.1–5 m | Regional (100–10,000 km²) | Weeks to years | High-res imagery, LiDAR, hyperspectral | High-resolution data, flexible sensor payloads, less weather-sensitive than satellites | Higher cost per area, limited temporal frequency, complex logistics |

| UAS (Drones) | 1–10 cm | Local (1–100 ha) | Hours to days | Ultra-high-res imagery, SfM point clouds, UAS-LiDAR | On-demand data, ultra-high resolution, below-canopy potential, low cost for local areas | Limited spatial extent, battery life constraints, regulatory restrictions, data processing challenges |

| In-Situ | Point measurements | Single point to plot | Minutes to seasonal | Physical samples, sensor readings, species counts | Direct measurements, high accuracy for parameters, essential for validation | Limited spatial extrapolation, labor-intensive, potentially dangerous terrain |

Table 2: Accuracy Performance and Cost Considerations

| Platform | Positional Accuracy | Spectral/Measurement Accuracy | Typical Applications | Relative Cost per Unit Area |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Satellite | Moderate to high (with correction) | High (radiometrically calibrated) | Land cover change, climate studies, vegetation phenology | Low to moderate |

| Airborne | High (with GPS/IMU) | High (laboratory-grade sensors possible) | Forest inventory, habitat mapping, 3D modeling | High |

| UAS | Very high (cm-level with GCPs) | Moderate (consumer-grade sensors common) | Individual plant/crown metrics, micro-topography, disturbance monitoring | Low (local), high (landscape) |

| In-Situ | Very high (survey-grade GPS) | Very high (direct measurement) | Species identification, soil properties, calibration/validation | Very high (when scaled) |

Experimental Protocols for Platform Validation

Data Science Competitions for Methodological Advancement

Open data science competitions have emerged as powerful tools for objectively comparing the performance of different algorithms and platforms using standardized datasets. The National Ecological Observatory Network (NEON) Plant Identification Challenge utilized precisely this approach to advance methods for converting remote sensing data into ecological information [3].

Experimental Methodology:

- Data Standardization: NEON Airborne Observation Platform (AOP) data—including high-resolution LiDAR and hyperspectral imagery—was paired with precisely geolocated field measurements of vegetation structure.

- Task Definition: Participants addressed three core tasks: (1) crown segmentation (identifying location/size of individual trees), (2) alignment (matching field trees with remote sensing detections), and (3) species classification.

- Evaluation Metrics: Algorithms were evaluated using consistent metrics including crown overlap percentage, alignment success rate, and species classification accuracy.

- Comparative Analysis: Six teams (16 participants) submitted predictions using diverse methods including support vector machines, random forests, gradient boosting, and neural networks.

Key Findings: The competition revealed significant methodological insights. Crown segmentation proved most challenging, with the highest-performing algorithm achieving only 34% overlap between remotely sensed crowns and field data, though performance improved for larger trees. Multiple algorithms excelled at species classification, with the highest-performing correctly identifying 92% of individuals across both common and rare species [3].

UAS Validation for Urban Environmental Assessment

Research in Phoenix, Arizona demonstrated a protocol for validating UAS against traditional satellite imagery for detecting neighborhood physical disorder [4].

Experimental Methodology:

- Platform Comparison: UAS-collected imagery (using a SenseFly Ebee with 18 MP camera) was directly compared to Landsat 8 satellite imagery available through Google Earth.

- Spatial Resolution Assessment: The capability to identify specific features of physical disorder (litter, graffiti, abandoned buildings) was quantified for both platforms.

- Ground Verification: Features identified in UAS imagery were ground-truthed for positional and categorical accuracy.

Key Findings: UAS imagery provided substantially improved detection capabilities, identifying 96.3% of physical disorder features compared to only 20.4% with Landsat 8 imagery. This confirmed UAS as a cost-effective, safe method for collecting hyper-local ecological and neighborhood data [4].

InSAR Versus Traditional Ground Monitoring

A 2025 comparison evaluated the capabilities of Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar (InSAR) against traditional ground monitoring methods for detecting ground deformation in agricultural and forestry contexts [5].

Experimental Methodology:

- Deformation Detection: Measured the minimum detectable ground movement using InSAR satellite technology versus traditional methods including manual surveying, soil sensors, and ground-penetrating radar.

- Spatial and Temporal Coverage: Compared the area coverage (km² per pass) and monitoring frequency between platforms.

- Cost Efficiency: Analyzed cost per square kilometer for each method.

Key Findings: InSAR demonstrated capability to detect ground deformation as small as 1 millimeter, while traditional methods often missed changes under 10 millimeters. InSAR covered thousands of square kilometers per pass at $2–10/km², compared to traditional methods covering 10–100 km² at $50–500/km² [5].

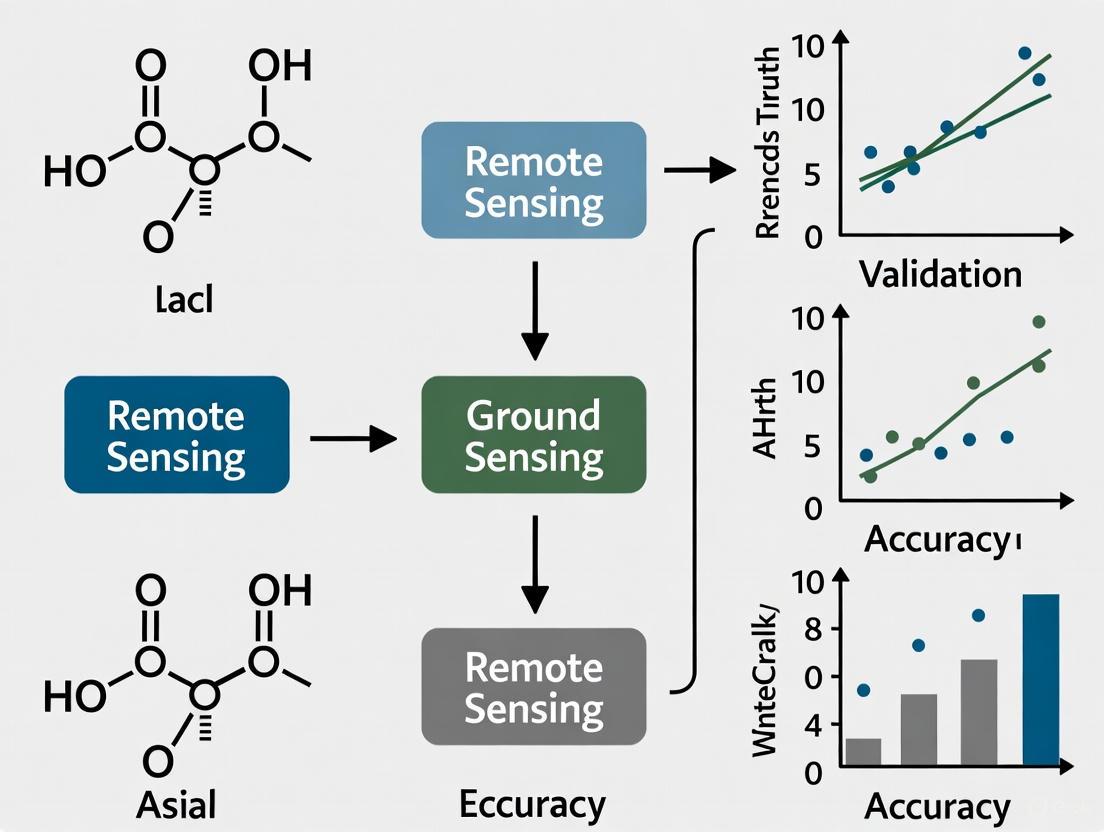

Integrated Workflow for Ecological Data Collection

The synergy between different remote sensing platforms and in-situ data creates a robust framework for ecological assessment. The following diagram illustrates how these components integrate within a typical research workflow.

Figure 1: Integrated workflow showing how multiple data platforms contribute to ecological insights, with in-situ data serving essential calibration and validation functions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Solutions

Successful ecological monitoring requires appropriate selection of technologies and methods tailored to specific research questions. This table details key solutions used across the featured experiments and their functional applications.

Table 3: Essential Research Solutions for Multi-Platform Ecology Studies

| Tool/Solution | Platform Category | Primary Function | Ecological Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| NEON AOP | Airborne | Provides standardized LiDAR and hyperspectral data across ecosystems | Continental-scale assessment of vegetation structure and composition [3] |

| InSAR Analytics | Satellite | Detects millimeter-scale ground deformation | Monitoring subsidence from groundwater extraction in agricultural areas [5] |

| UAS with SfM-MVS | UAS | Generates ultra-high-resolution 3D models from overlapping imagery | Individual tree crown delineation and micro-topography mapping [1] [6] |

| RSEI (Remote Sensing Ecological Index) | Satellite/UAS | Integrates greenness, dryness, humidity, and heat for quality assessment | Urban ecological quality monitoring using Sentinel-2 and Landsat data [7] |

| GEO-Detector | Software | Statistically explores spatial heterogeneity and driving factors | Analyzing influence of urban factors on ecological quality [7] |

| Multi-Sensor Probes | In-Situ | Measures physical and chemical parameters in real-time | Water quality monitoring (temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen) [8] |

| Support Vector Machines | Algorithm | Classifies species from spectral features | Tree species identification from hyperspectral data [3] |

The accurate assessment of ecological systems requires thoughtful integration of multiple data platforms, each contributing unique strengths to address different aspects of ecological complexity. Satellite systems provide the broad-scale context for continental and global processes, while airborne platforms offer higher-resolution regional assessments. UAS deliver unprecedented detail at the individual organism level, and in-situ measurements provide the essential ground truth for validating all remote observations. The future of ecological monitoring lies not in selecting a single superior platform, but in strategically combining these complementary technologies, using standardized experimental protocols and validation frameworks to ensure data quality and cross-study comparability. As technological advancements continue to improve the resolution, accessibility, and analytical power of these platforms, their integrated application will become increasingly essential for addressing complex ecological challenges across scales.

The Critical Role of Accuracy Assessment in Ecological Monitoring

Accurate ecological monitoring is fundamental to understanding environmental change, evaluating conservation policies, and ensuring sustainable resource management. The emergence of diverse methodologies, particularly remote sensing and ground-based techniques, has created a critical need to systematically assess and compare their accuracy. This guide examines the performance of these approaches, providing a structured comparison of their capabilities, limitations, and optimal applications for researchers and scientists.

The Fundamental Need for Accuracy Assessment

All ecological data, whether from satellites or field surveys, contain inherent uncertainties. Accuracy assessment is the process of quantifying these uncertainties, transforming raw data into reliable evidence for scientific and policy decisions. In remote sensing, a classification map's quality is fundamentally defined by its User's Accuracy (UA) and Producer's Accuracy (PA), which measure commission and omission errors, respectively [9].

The core challenge is that simple methods like pixel-counting for area estimation are often biased due to these errors [9]. Without rigorous validation, monitoring programs risk generating misleading conclusions. For instance, the apparent area of a land-cover class can be significantly over- or under-estimated if the map's accuracy is not accounted for. Therefore, robust assessment frameworks, such as stratified random sampling where classification maps serve as stratification, are recommended to control bias and generate reliable area estimates [9].

Remote Sensing vs. Ground-Based Methods: A Performance Comparison

The choice between remote sensing and ground-based methods involves trade-offs between spatial coverage, resolution, cost, and accuracy. The table below summarizes the core characteristics of each approach.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Ecological Monitoring Methods

| Feature | Remote Sensing | Ground-Based Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Coverage | Extensive regional to global scales [10] | Localized, point-specific measurements |

| Temporal Resolution | Regular revisits (e.g., days to weeks) [10] | Variable, often seasonal or sporadic |

| Data Type | Spectral, spatial, and structural proxies [11] | Direct species identification and physical measurements |

| Primary Strengths | Synoptic views, historical archive analysis, access to remote areas [10] | High taxonomic precision, validation of proxy data, detailed local context |

| Key Limitations | Spectral confusion, signal attenuation, requires ground validation [9] [11] | Labor-intensive, limited spatial extrapolation, potentially high cost |

Integrating these methods often yields the highest accuracy. A study on mapping protected forest habitats combined Sentinel-2 satellite data with ground-based phytosociological surveys using a deep learning algorithm. This integration achieved a remarkable field validation accuracy of 98.33%, demonstrating the power of a combined approach [12].

Experimental Evidence: Quantifying Accuracy in Practice

Case Study 1: Multi-Source Land Use Classification

A 2024 study introduced a new strategy to improve Land Use/Cover Change (LUCC) classification accuracy by fusing UAV LiDAR and hyperspectral imagery [11].

- Experimental Protocol: Researchers extracted 157 features from LiDAR (e.g., intensity, height) and hyperspectral data (e.g., spectral, texture). They developed a new feature extraction algorithm (CFW) and a dimensionality reduction method (SS-PCA) to identify the optimal feature subset, which was then classified using a Random Forest classifier [11].

- Results and Accuracy: The fusion of LiDAR and hyperspectral data significantly outperformed either data source alone, mitigating issues like 'salt and pepper noise' [11].

Table 2: Classification Accuracies from Multi-Source Data Fusion [11]

| Data Source | Overall Accuracy (%) | Key Contributing Features |

|---|---|---|

| LiDAR Only | 78.10% | Height and intensity information |

| Hyperspectral Only | 89.87% | Spectral indices and texture |

| LiDAR + Hyperspectral | 97.17% | Combined structural and spectral features |

Case Study 2: Evaluating Ecological Restoration Programs

Assessing the effectiveness of large-scale Ecological Restoration Programs (ERPs) requires robust methods to isolate their impact from other natural and human factors.

- Experimental Protocol: A 2025 study treated China's National Key Ecological Function Areas (NKEFAs) as a quasi-natural experiment [13]. Using a time-varying Difference-in-Differences (DID) model on panel data from 329 cities (2001-2021), the study compared ecological conditions in NKEFAs with control areas to establish a causal link between the policy and ecological outcomes [13].

- Results and Accuracy: This counterfactual approach demonstrated that the ERP significantly increased Net Primary Productivity (NPP), a key indicator of vegetation recovery. The rigorous methodology provided a more credible assessment of the program's true ecological effectiveness, controlling for confounding variables that often plague simpler before-after or cross-sectional comparisons [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Research Solutions

Successful ecological monitoring relies on a suite of tools and data solutions.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for Ecological Monitoring

| Tool/Solution | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Landsat & Sentinel-2 Data | Provides multi-decadal, medium-resolution optical imagery for change detection. | Tracking deforestation, agricultural expansion, and urbanization [10] [14]. |

| Analysis Ready Data (ARD) | Pre-processed satellite data (radiometric, atmospheric correction) that is ready for analysis. | Reduces data processing costs and facilitates large-scale, time-series analysis [15]. |

| UAV LiDAR & Hyperspectral Sensors | Captures high-resolution, 3D structural and detailed spectral information from unmanned aerial vehicles. | Fine-scale land use classification and invasive species mapping (e.g., Spartina alterniflora) [15] [11]. |

| Google Earth Engine (GEE) | A cloud-computing platform for planetary-scale geospatial analysis. | Processing long-term satellite data archives to calculate ecological indices like RSEI [10]. |

| Stratified Random Sampling | A statistical sampling design that uses a classification map for stratification. | Provides unbiased area estimates and optimizes field validation efforts [9]. |

| Cellular Automata-Markov (CA-Markov) Model | Integrates cellular automata with Markov chains to simulate future land-use changes. | Predicting future ecological quality based on historical trends [10]. |

Workflow for Integrated Ecological Monitoring

The diagram below illustrates a robust, integrated workflow for ecological monitoring that embeds accuracy assessment at every stage.

Integrated Ecological Monitoring Workflow

Key Insights for Researchers

- Map Accuracy Directly Influences Efficiency: In stratified estimation, higher map accuracy (PA and UA) reduces the sample size needed to achieve a target precision or yields better precision for a fixed sample size [9]. The impact of PA and UA on estimation efficiency is nonlinear and varies with the target area proportion [9].

- Spatial Validation is Critical: A common pitfall in ecological modeling is using non-spatial validation, which can lead to over-optimistic assessments of model predictive power. Spatially independent validation is essential for a true accuracy estimate [16].

- Embrace Analysis Ready Data (ARD): Leveraging ARD can dramatically reduce the time and expertise required for data pre-processing, making remote sensing more accessible and reproducible for a wider range of researchers [15].

From Theory to Practice: Methodologies for Data Integration and Accuracy Assessment

Designing Robust Validation Data Collection Strategies

Validation through independent means is the cornerstone of producing reliable remote sensing data products and ground-based ecological measurements [17]. This process assesses the quality of data products derived from system outputs, serving as the essential bridge between raw observations and scientifically defensible conclusions [17]. In the context of ecological monitoring and climate research, robust validation strategies determine whether data possesses sufficient accuracy for operational application, informing critical decisions in conservation policy, resource management, and climate change mitigation [18] [19]. Without rigorous validation, even the most technologically advanced sensing systems can produce misleading results, potentially compromising environmental management decisions and scientific findings.

The fundamental challenge in validation stems from the inherent complexity of comparing datasets collected at different scales, through different methodologies, and with varying inherent uncertainties [20]. Ground-based measurements provide direct observations but are limited in spatial coverage, while remote sensing offers synoptic coverage but involves indirect retrievals of ecological parameters [20] [17]. This article provides a comprehensive comparison of validation approaches for remote sensing and ground-based ecological data, offering experimental protocols, analytical frameworks, and practical guidance for researchers designing validation campaigns in environmental and ecological studies.

Comparative Framework: Remote Sensing vs. Ground-Based Validation

Fundamental Characteristics and Trade-offs

Remote sensing and ground-based monitoring methods offer complementary strengths for ecological validation, with distinct operational characteristics and methodological approaches. Table 1 summarizes the key comparative aspects of these approaches, highlighting their respective advantages and limitations in validation contexts.

Table 1: Comparative Characteristics of Remote Sensing and Ground-Based Validation Approaches

| Evaluation Criteria | Remote Sensing Validation | Ground-Based Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Coverage | Thousands of km² per pass; >90% global agricultural land coverage [5] | Limited to 10-100 km² per operation; ~30-40% global agricultural land coverage [5] |

| Spatial Resolution | 10-100 meters (typical 2025 range) [5] | Centimeter to meter level (highly localized) [5] |

| Temporal Frequency | Daily/weekly revisits; continuous monitoring capability [5] | Point-in-time measurements; biweekly to monthly intervals [5] |

| Data Accuracy Range | 85%-95% for large-scale deformation tracking [5] | 98%+ for localized parameter measurement [5] |

| Measurement Type | Proxy measurements through spectral response; indirect retrieval algorithms [20] [17] | Direct measurement of specific parameters; physical sampling [5] |

| Key Limitations | Atmospheric interference, spatial scale mismatches, indirect retrievals [18] [17] | Limited spatial representation, labor-intensive, inaccessible terrain challenges [5] [20] |

| Cost Efficiency | $2-10/km² (subscription/platform-based) [5] | $50-500/km² (manual labor and equipment) [5] |

Accuracy Assessment Methodologies

Accuracy assessment for remote sensing products typically employs statistical comparisons between classified imagery and reference data, with the error matrix (confusion matrix) serving as the foundational analytical tool [21] [22]. This pixel-by-pixel comparison quantifies agreement between remote sensing classifications and reference data assumed to represent reality [21]. Standard practice includes calculation of overall accuracy, producer's accuracy (measure of omission error), user's accuracy (measure of commission error), and Kappa coefficient (which assesses agreement beyond chance) [21].

Despite established methodologies, significant challenges remain in implementation. A comprehensive review of accuracy assessment practices found that only 56% of studies explicitly included an error matrix, and a mere 14% reported overall accuracy with confidence intervals [22]. Furthermore, only 32% of papers included accuracy assessments considered reproducible—incorporating probability-based sampling, complete error matrices, and sufficient characterization of reference datasets [22]. These deficiencies highlight the need for more rigorous and standardized validation reporting across the discipline.

Experimental Protocols for Validation Data Collection

Remote Sensing Accuracy Assessment Protocol

The following workflow outlines a standardized approach for validating remote sensing classification products, adaptable to various ecological and land cover mapping applications:

Reference Data Selection: Secure high-resolution aerial imagery or field-collected data that closely matches the acquisition date of the remote sensing product being validated [21]. Temporal alignment is critical to minimize discrepancies due to actual landscape changes.

Sampling Design: Implement a probability-based sampling scheme to collect reference data, typically using stratified random sampling based on map classes [22] [19]. The sample size should be determined considering spatial autocorrelation and heterogeneity, with methods available to calculate optimal sampling numbers [19].

Spatial Registration: Precisely align the remote sensing image and reference data to the same coordinate system and spatial resolution [21]. The Create Accuracy Assessment Points tool in GIS platforms can automate extraction of class values at sample locations [21].

Reference Data Collection: For each sample point, identify the "ground truth" informational class through expert interpretation of high-resolution imagery or field visits [21]. Document classification rules and decision protocols to maintain consistency.

Error Matrix Construction: Tabulate classified data against reference data in a contingency table, with rows typically representing reference data and columns representing the map classification [21] [22].

Accuracy Metrics Calculation: Compute overall accuracy, producer's accuracy, user's accuracy, and Kappa coefficient from the error matrix [21]. Report confidence intervals where possible to quantify uncertainty [22].

Thematic Accuracy Assessment: Analyze patterns of confusion between classes to identify systematic classification errors and inform algorithm improvements [21].

The figure below illustrates this workflow as a sequential process:

Ground-Based Validation Protocol for Satellite Products

Validating coarse-resolution satellite products with ground-based measurements requires specialized approaches to address scale mismatches:

Site Selection: Establish intensive study areas within homogeneous landscapes or strategically locate sites to characterize heterogeneity [17]. The number and distribution of sites should capture the environmental gradient of interest.

In Situ Sensor Deployment: Deploy calibrated sensors (e.g., soil moisture probes, water level loggers, temperature loggers) following standardized protocols [20]. Ensure continuous temporal monitoring to match satellite overpass times.

Field Campaigns: Conduct coordinated field measurements during satellite overpasses, collecting data on relevant biophysical parameters (e.g., vegetation structure, soil properties, water quality) [20] [17].

Upscaling Methodology: Develop spatial aggregation techniques to translate point-based ground measurements to the spatial scale of satellite pixels [17]. This may involve distributed sensor networks, transect sampling, or geostatistical interpolation.

Uncertainty Quantification: Characterize uncertainty components including measurement error, spatial representativeness error, and temporal alignment error [17].

Comparison Analysis: Implement statistical analyses comparing ground-based estimates at pixel scale with satellite retrievals, accounting for uncertainty in both datasets [17].

The integration of these approaches is particularly valuable for ecological studies, where ground measurements provide specific habitat changes and effects on populations, while satellite-based observations offer broader landscape context [20].

Integrated Validation Framework

Strategic Integration of Approaches

An Integrated Framework combining Experimental and Big Data approaches offers substantial opportunities for leveraging the strengths of both validation methodologies [23]. This framework recognizes that Big Data (including remote sensing) can document and monitor patterns across spatial scales, while experimental approaches (including targeted ground-based monitoring) can deliver direct assessments of perturbations relevant for conservation interventions [23].

Successful integration requires collaboration throughout the scientific process: hypothesis generation, design and implementation, analysis, and interpretation [23]. Practical implementation includes embedding ground-based experiments within the broader spatial context provided by remote sensing, and using remote sensing to identify locations where intensive ground-based studies would be most informative [23]. This approach is particularly valuable for problems requiring understanding across spatial and temporal scales, forecasting, and delimiting the spatial scale at which stressors operate [23].

Addressing Scale Discontinuities

A fundamental challenge in validation arises from scale mismatches between ground-based measurements (points) and remote sensing observations (pixels) [20] [17]. Table 2 summarizes common scale-related challenges and potential solutions in validation studies.

Table 2: Scale-Related Challenges and Solutions in Validation Data Collection

| Challenge | Impact on Validation | Potential Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Mismatch | Point measurements may not represent heterogeneous pixel areas [17] | Distributed sensor networks, transect sampling, strategic site selection in homogeneous areas [17] |

| Temporal Mismatch | Instantaneous ground measurements may not match integrated satellite observations [18] | Continuous ground monitoring, temporal interpolation, matching acquisition times [20] |

| Definitional Inconsistency | Different conceptual definitions of the same parameter across methods [20] | Harmonized operational definitions, cross-walking frameworks between measurement approaches |

| Support Scale Difference | Spatial resolution determines what ecological structures can be detected [20] | Multi-scale sampling designs, geostatistical approaches, acknowledgment of inherent limitations |

Research comparing wetland-rich landscapes found that responses of 4 km² landscape blocks generally paralleled changes measured on the ground, but ground-based measurements were more dynamic, with changes critical for biota not always apparent in satellite proxies [20]. This highlights the importance of complementary multi-scale approaches rather than assuming perfect correspondence between methods.

Essential Research Toolkit for Validation Studies

Field Data Collection Equipment

Table 3: Essential Equipment for Ground-Based Validation Data Collection

| Equipment Category | Specific Examples | Primary Applications in Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Positioning Systems | Differential GPS, RTK-GPS | Precise geolocation of sample sites for spatial alignment with remote sensing data [20] |

| Environmental Sensors | Soil moisture probes, water level loggers, air temperature loggers [20] | Continuous monitoring of parameters comparable to satellite-derived products [20] [17] |

| Acoustic Recorders | Automated acoustic recording units [20] | Monitoring biodiversity indicators (e.g., amphibian calls) as ecological validation metrics [20] |

| Spectroradiometers | Field spectroradiometers | Measuring spectral signatures for direct comparison with remote sensing reflectance values [17] |

| Vegetation Sampling Tools | Densiometers, leaf area index meters, canopy analyzers | Measuring vegetation structure parameters to validate land cover and biophysical products [17] |

Analytical Tools and Software

Table 4: Analytical Tools for Validation Data Analysis

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Validation Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Geographic Information Systems | ArcGIS Pro, QGIS | Spatial alignment, sampling design, error matrix creation [21] |

| Statistical Software | R, Python with spatial libraries | Accuracy assessment, uncertainty quantification, spatial statistics [22] [19] |

| Cloud Computing Platforms | Google Earth Engine | Processing multi-temporal remote sensing data for validation comparisons [10] |

| Specialized Validation Tools | CREATE ACCURACY ASSESSMENT POINTS (ArcGIS) [21] | Generating random points for accuracy assessment with automated class value extraction [21] |

Robust validation strategies for both remote sensing and ground-based ecological monitoring require careful attention to sampling design, scale considerations, and uncertainty quantification. While remote sensing offers unprecedented spatial coverage and temporal frequency, ground-based methods provide essential direct measurements and localized accuracy. The most effective validation frameworks strategically integrate both approaches throughout the scientific process [23].

Future advances in validation methodology will likely focus on improving scale-aware validation techniques, developing more sophisticated uncertainty quantification frameworks, and creating more inclusive approaches that incorporate traditional ecological knowledge and citizen science [18]. Additionally, as remote sensing technologies continue evolving with higher spatial, temporal, and spectral resolutions, validation approaches must similarly advance to address new challenges and opportunities [22] [17].

Transparent reporting of validation methodologies remains essential for building trust in environmental data products. Researchers should clearly document sampling designs, reference data characteristics, accuracy metrics with confidence intervals, and limitations to enable proper interpretation and reproducibility [22]. By adopting rigorous, integrated validation strategies, the scientific community can enhance the reliability of ecological assessments and strengthen the evidence base for environmental decision-making.

Stratified Random and Other Sampling Techniques for Unbiased Assessment

In ecological research, particularly in studies that integrate remote sensing with ground-based data, the sampling strategy is a fundamental determinant of the validity and reliability of the findings. Remote sensing provides extensive spatial coverage, but its accuracy must be verified through ground observations, making unbiased sampling essential for robust model calibration and validation. The choice of sampling technique directly impacts the precision of area estimation, the accuracy of biomass calculations, and the overall credibility of ecological quality assessments. Stratified random sampling has emerged as a particularly powerful method in this context, as it systematically addresses the challenges of spatial heterogeneity and class rarity that often complicate ecological studies. This guide provides a comparative analysis of stratified random sampling against other common techniques, examining their performance, experimental protocols, and suitability for various research scenarios in ecological assessment.

Comparative Analysis of Sampling Techniques

Table 1: Comparison of Key Sampling Techniques for Ecological Assessment

| Sampling Technique | Core Principle | Strengths | Limitations | Ideal Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stratified Random Sampling | Divides population into non-overlapping strata (e.g., based on vegetation density, land cover); random samples taken from each stratum [24]. | Improves representativeness of heterogeneous areas; increases statistical efficiency; ensures rare classes are adequately sampled [24] [25]. | Requires prior knowledge for stratification; stratum definition can introduce bias if incorrect. | Estimating area of rare land cover classes (e.g., forest loss); validating maps in complex, heterogeneous environments [25]. |

| Simple Random Sampling (SRS) | Every possible sample of a given size has an equal probability of being selected. | Unbiased; simple design and analysis. | Statistically inefficient for rare classes or heterogeneous areas; can miss important spatial variations [26]. | Homogeneous study areas where no prior spatial information is available. |

| Systematic Sampling (SYS) | Sample units are selected at a fixed interval (e.g., every kth unit) across the study area. | Ensures even spatial coverage; easy to implement. | Vulnerable to bias if the spatial pattern aligns with the sampling interval. | Large-scale surveys where periodic patterns are not a concern. |

| Spatially Balanced Sampling (e.g., GRTS, BAS) | Uses complex algorithms to select samples that are spatially balanced over the study area. | Excellent spatial coverage; good for capturing gradients. | Complex implementation; computationally intensive. | Regional-scale environmental monitoring where even coverage is critical [26]. |

| Optimized/Complexity-Based Sampling | Uses prior remote sensing data (e.g., NDVI) to guide sampling towards areas of high complexity or heterogeneity [27] [26]. | Maximizes information gain per sample; improves model generalizability. | Highly dependent on the quality and relevance of the prior data. | Validating medium- to high-resolution remote sensing products; working with limited sampling budgets [26] [28]. |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison from Experimental Studies

| Study & Context | Sampling Technique | Key Performance Metric | Result | Sample Size for Target Precision |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vegetation Indices Validation [26] | INTEG-STRAT (Stratified based on NDVI) | Correlation with prior knowledge (R²) | Achieved 80% correlation | 70 points |

| Simple Random Sampling (SRS) | Correlation with prior knowledge (R²) | Achieved 80% correlation | Required more than 70 points | |

| Spatial Systematic Sampling (SYS) | Correlation with prior knowledge (R²) | Achieved 80% correlation | Required more than 70 points | |

| Mangrove Carbon Estimation [24] | Stratified Random Sampling | Correlation with field Cag (r) | 0.847 | 30 plots for model development |

| Area Estimation of a Rare Class (≤10%) [25] | Stratified Sampling (Optimal allocation) | Relative Efficiency (Precision) | Can be 2-5x more efficient than simple random sampling for the same sample size. | Varies with User's/Producer's accuracy targets |

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Stratified Random Sampling for Mangrove Carbon Stock Assessment

This protocol is based on a study in West Bali, Indonesia, which successfully used stratified random sampling to estimate above-ground carbon (Cag) in mangrove forests using Sentinel-2 imagery [24].

- Define Strata: The mangrove forest area is divided into distinct strata. The West Bali study used characteristics like vegetation density, tidal influence, and soil composition to define these strata [24].

- Proportional Allocation: The total number of sampling plots is allocated to each stratum in proportion to its area to enhance statistical robustness and minimize error [24].

- Plot Placement: Within each stratum, square transect plots (e.g., 10 m × 10 m) are randomly positioned. The GPS coordinates of each plot are recorded for spatial accuracy [24].

- Field Data Collection: Within each plot, measure the circumference of all individual mangrove trees at breast height (CBH, 1.3 m above ground). Convert CBH to Diameter at Breast Height (DBH) using the formula: DBH = CBH / π [24].

- Carbon Calculation: Use species-specific or generic allometric equations to convert DBH measurements into estimates of above-ground biomass (Bag), and then to above-ground carbon (Cag) [24].

- Model Development and Validation: Use a portion of the collected data (e.g., 30 plots) to develop a regression model linking field-measured Cag with remote sensing vegetation indices (e.g., Simple Ratio index). Use the remaining independent data (e.g., 15 plots) to validate the model's reliability [24].

Protocol: INTEG-STRAT Strategy for Validating Vegetation Indices

This protocol outlines the INTEG-STRAT strategy, an integrative stratified sampling approach designed for validating medium- and high-resolution vegetation index (VI) products over heterogeneous surfaces [26].

- Acquire Prior Knowledge: Obtain a high-resolution VI map (e.g., a Sentinel-2 NDVI image) of the study area a few days before the field campaign. This serves as the stratification basis [26].

- Stratification: The prior NDVI image is classified into several strata representing different vegetation density levels.

- Sampling Optimization: The core of INTEG-STRAT is determining the optimal combination of a spatial sampling method (e.g., SRS, SYS) and the stratification scheme. The objective rule is to minimize the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) of a 10-fold cross-validation between estimated values and the corresponding values on the prior knowledge image [26].

- Field Data Collection: Navigate to the pre-determined sampling points and collect in-situ measurements of the target biophysical variable (e.g., LAI, chlorophyll content) that corresponds to the VI being validated.

- Efficiency Evaluation: The strategy's effectiveness is evaluated using metrics like relative precision, correlation coefficient, and RMSE, and is compared against non-optimized methods [26].

Workflow Diagram: Stratified Random Sampling for Remote Sensing Validation

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for implementing a stratified random sampling approach in a remote sensing validation study.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Tools and Materials for Sampling-Based Ecological Research

| Tool/Material | Function in Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Sentinel-2 Satellite Imagery | Provides high-resolution (10-20m) multispectral data with frequent revisit times. Used to derive vegetation indices and create stratification maps [24]. | Calculating the Simple Ratio (SR) index to model mangrove carbon stocks [24]. |

| Landsat 8/9 Satellite Imagery | Offers a long-term, consistent archive of medium-resolution (30m) data. Essential for change detection and long-term trend analysis [10]. | Used in calculating the Remote Sensing Ecological Index (RSEI) for monitoring ecological quality over decades [10]. |

| GPS Receiver | Provides precise geographic coordinates for locating sampling plots in the field, ensuring spatial alignment with satellite pixels [24]. | Recording the location of 10m x 10m transect plots in a mangrove forest [24]. |

| Dendrometer or Tape Measure | Used to measure tree circumference or diameter at breast height (DBH), a critical input for allometric biomass equations [24]. | Measuring CBH of mangrove trees within a sample plot to calculate DBH [24]. |

| Allometric Equations | Species-specific mathematical models that estimate biomass (and thus carbon) from tree measurements like DBH [24]. | Converting field-measured DBH into estimates of above-ground carbon (Cag) [24]. |

| Google Earth Engine (GEE) | A cloud-computing platform for geospatial analysis. Allows rapid processing of large satellite imagery archives [10]. | Processing multi-temporal Landsat imagery to compute RSEI over large areas [10]. |

| Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) | A spectral index derived from satellite imagery that quantifies vegetation greenness and health. Serves as excellent prior knowledge for stratification [26]. | Used in the INTEG-STRAT strategy to define strata for optimal sample placement [26]. |

Constructing and Interpreting the Confusion Matrix (Error Matrix)

Within the rigorous framework of scientific research, particularly in fields utilizing classification models—from drug development to ecological monitoring—the performance of a predictive algorithm cannot be captured by a single metric. The confusion matrix, also known as an error matrix, is a foundational tool that provides a detailed breakdown of a classification model's performance against a known set of results [29] [30]. In the context of assessing the accuracy of remote sensing data versus ground-based ecological observations, the confusion matrix moves beyond simplistic accuracy rates. It offers a nuanced diagnostic that reveals not just how often a model is right, but, more critically, where it goes wrong and what types of errors it makes [31]. This granular insight is indispensable for validating remote sensing products, such as land cover classifications or ecological quality maps, against field-surveyed "ground truth," enabling researchers to quantify uncertainty and refine their models for more reliable environmental and biomedical applications [10] [30] [32].

Core Components of a Confusion Matrix

A confusion matrix is a specific table layout that allows for visualization of an algorithm's performance [29]. Its structure is built upon four fundamental outcomes derived from comparing predicted classes to actual classes.

The Four Fundamental Outcomes

For a binary classification problem, the matrix is a 2x2 table that categorizes every prediction into one of the following quadrants [31] [33]:

- True Positive (TP): The model correctly predicts the positive class. (e.g., A pixel is correctly classified as "forest" by a remote sensing algorithm, and it is forest according to ground survey [30]).

- True Negative (TN): The model correctly predicts the negative class. (e.g., A pixel is correctly classified as "water," and it is water [30]).

- False Positive (FP): The model incorrectly predicts the positive class when the actual is negative. Also known as a Type I error. (e.g., A pixel of "bare soil" is misclassified as "forest" [30] [33]).

- False Negative (FN): The model fails to predict the positive class when the actual is positive. Also known as a Type II error. (e.g., A "forest" pixel is misclassified as "grassland" [30] [33]).

Matrix Structure and Multi-class Extension

The standard binary matrix can be extended to an N x N table for multi-class problems, where N is the number of classes [31]. In this structure:

- Rows typically represent the actual classes from validation data (ground truth).

- Columns represent the predicted classes from the model.

- The diagonal cells (from top-left to bottom-right) show the counts of correct classifications for each class.

- The off-diagonal cells visualize misclassifications, revealing which classes are most frequently confused with one another [30] [31].

Table 1: Example Confusion Matrix for a Land Cover Classification Task

| Actual vs. Predicted | Forest | Water | Grassland | Bare Soil | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forest | 56 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 62 |

| Water | 1 | 67 | 1 | 0 | 69 |

| Grassland | 5 | 0 | 34 | 7 | 46 |

| Bare Soil | 2 | 0 | 9 | 42 | 53 |

| Total | 64 | 67 | 48 | 51 | 230 |

Key Performance Metrics Derived from the Confusion Matrix

The counts within the confusion matrix are used to calculate critical performance metrics that each provide a different perspective on model quality [29] [34].

Metric Definitions and Formulas

The most common metrics derived from the confusion matrix are:

- Accuracy: The overall correctness of the model.

Accuracy = (TP + TN) / (TP + TN + FP + FN)[35] [34]. - Precision: The model's ability to avoid false positives. When it predicts positive, how often is it correct?

Precision = TP / (TP + FP)[35] [34]. - Recall (Sensitivity or True Positive Rate): The model's ability to identify all actual positive instances.

Recall = TP / (TP + FN)[35] [34]. - F1-Score: The harmonic mean of Precision and Recall, providing a single balanced metric.

F1-Score = 2 * (Precision * Recall) / (Precision + Recall)[29] [35]. - Specificity (True Negative Rate): The model's ability to identify actual negative instances.

Specificity = TN / (TN + FP).

Interpreting Metrics for Model Evaluation

The utility of each metric depends heavily on the research context and the cost associated with different types of errors [34].

- Accuracy is a good initial measure but can be highly misleading with imbalanced datasets. A model that always predicts the majority class will have high accuracy but poor practical utility [35] [31].

- Precision is critical when the cost of a false positive is high. In a medical screening test, high precision means that when a test comes back positive, we can be very confident the patient has the condition, minimizing unnecessary stress and follow-up procedures [31] [34].

- Recall is critical when the cost of a false negative is high. In disease diagnosis or spam filtering, high recall ensures that most actual cases are caught, minimizing missed detections [31] [34].

- F1-Score is the preferred metric when seeking a balance between Precision and Recall, especially when class distribution is uneven [29] [31].

Table 2: Performance Metrics Calculated from the Example Confusion Matrix

| Metric | Formula (from matrix) | Calculation | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Accuracy | (TP+TN)/Total | (56+67+34+42)/230 | 86.5% |

| Precision (Forest) | TP / (Col Total Forest) | 56 / 64 | 87.5% |

| Recall (Forest) | TP / (Row Total Forest) | 56 / 62 | 90.3% |

| F1-Score (Forest) | 2(PrecRec)/(Prec+Rec) | 2(0.8750.903)/(0.875+0.903) | 88.9% |

| User's Accuracy (Forest) | TP / (Row Total Forest) | 56 / 62 | 90.3% |

| Producer's Accuracy (Forest) | TP / (Col Total Forest) | 56 / 64 | 87.5% |

In remote sensing, the metrics User's Accuracy and Producer's Accuracy are commonly used. User's Accuracy, equivalent to Precision, answers the question: "If I use this map and see a pixel labeled as 'Forest,' how likely is it to actually be forest?" Producer's Accuracy, equivalent to Recall, answers: "If an area is truly forest, how likely was it to be correctly mapped as such?" [30].

Experimental Protocol for Accuracy Assessment

A robust accuracy assessment, culminating in a reliable confusion matrix, requires a meticulous methodology for collecting and comparing data.

Workflow for Remote Sensing Validation

The following workflow outlines the standard protocol for validating a remote sensing-based classification, such as a land cover map, using ground-based reference data [30].

Detailed Methodologies for Key Steps

- Generating the Validation Dataset: A stratified random sampling approach is recommended to ensure all classes are adequately represented. This involves randomly selecting a sufficient number of sample points within the spatial extent of each mapped class [30]. The number of samples per class should be determined based on the relative area of each class or a pre-defined minimum (e.g., 50-100 samples per class) to ensure statistical significance [30].

- Collecting Ground Reference Data: This "ground truth" can be acquired through:

- Field Surveys: Georeferenced field observations using GPS and photography, documenting the dominant land cover within the area corresponding to the remote sensing pixel (e.g., a 30m x 30m area for Landsat) [30].

- Visual Interpretation of High-Resolution Imagery: Using platforms like Google Earth to visually identify land cover at sample points when field campaigns are not feasible. The interpreter must be able to distinguish all classes confidently [30].

- Pre-existing Ground-based Ecological Data: Utilizing systematically collected field data, such as national forest inventories or ecological surveys conducted by environmental agencies [32].

- Constructing the Confusion Matrix: The predicted class from the remote sensing map for each sample point is compared to the reference class from the ground data. The counts of agreements and disagreements for all class pairs are then tabulated into the N x N confusion matrix [30].

For researchers conducting accuracy assessments in ecological remote sensing, the following tools and data sources are essential.

Table 3: Essential Research Toolkit for Accuracy Assessment

| Tool / Resource | Function & Explanation |

|---|---|

| Ground Reference Data | The "ground truth" against which the classification is compared. It can be derived from field surveys or high-resolution imagery and must be consistent with the classification scheme [30]. |

| Stratified Random Sampling Protocol | A methodological framework for selecting validation points that ensures statistical robustness and representation across all classes, preventing biased accuracy estimates [30]. |

| Remote Sensing Software (e.g., GEE, QGIS, ENVI) | Platforms used to perform the initial land cover classification and extract the predicted class labels for each validation point [10]. |

| Statistical Computing Environment (e.g., R, Python with scikit-learn) | Programming environments with specialized libraries that automate the construction of confusion matrices and calculation of all derivative performance metrics [29] [31]. |

| High-Resolution Satellite Imagery (e.g., Google Earth) | A critical resource for generating validation data through visual interpretation when extensive field work is not possible, ensuring spatial correspondence with the classified map [30]. |

Comparative Analysis: Remote Sensing vs. Ground-Based Assessment

The confusion matrix provides a quantitative framework for directly comparing the performance of different classification approaches, such as traditional field-based methods versus modern remote sensing techniques enhanced with deep learning.

Table 4: Comparative Performance of Classification Models in Ecological Studies

| Study Focus / Model Type | Reported Performance Metrics | Key Findings & Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Ecological Quality Prediction (U-Net vs. Random Forest) [32] | U-Net (Deep Learning): Consistently higher overall accuracy than RF across all tested schemes and maps.Random Forest (Pixel-based): Lower overall accuracy compared to U-Net. | Deep learning models (U-Net), which extract complex spatial-contextual features from imagery, outperform traditional pixel-based machine learning (Random Forest) in predicting ecological conservation values. This highlights the importance of spatial patterns in ecological assessment. |

| Land Cover Classification (Example Matrix) [30] | Overall Accuracy: 86.5%User's Accuracy (Water): 97%Producer's Accuracy (Grassland): 71% | The matrix reveals that while the model is excellent at identifying water, it struggles more with grasslands, which are often misclassified as bare soil or forest. This pinpoints specific areas for model improvement. |

| Tuberculosis Detection (ResNet50) [31] | Accuracy: 91%Precision: 80%Recall: 90.9% | The high recall is critical in a medical context, ensuring most TB cases are detected. The lower precision indicates a trade-off, with some false alarms that may lead to unnecessary further testing. |

The confusion matrix is an indispensable diagnostic tool that moves beyond simplistic accuracy metrics to provide a complete picture of a classification model's performance. By systematically breaking down predictions into true positives, false positives, false negatives, and true negatives, it empowers researchers in ecology, drug development, and beyond to identify specific error patterns, understand critical trade-offs between precision and recall, and make informed decisions about model selection and refinement [29] [31] [34]. In the critical task of validating remote sensing data products against ground-based observations, the confusion matrix provides the transparent, quantitative evidence base needed to assign confidence to scientific findings and support sound environmental policy and management decisions [30] [32].

In the field of ecological research, the maps and classifications generated from remote sensing data are models—simplifications of reality that inevitably contain some degree of error [30]. Accuracy assessment quantifies this error, determining whether a map is suitable for its intended purpose, be it monitoring deforestation, assessing habitat health, or tracking urbanization [22]. For researchers and drug development professionals relying on geospatial data for environmental context, understanding map accuracy is not merely an academic exercise; it is fundamental to ensuring the validity of their analyses and conclusions.

The cornerstone of this process is the comparison of the map's estimates against trusted reference data, often called "ground truth" or "validation data" [30]. This practice is encapsulated within a confusion matrix (also known as an error matrix or contingency table), which provides a complete picture of classification performance [30] [22]. From this matrix, three key metrics are derived: User's Accuracy, Producer's Accuracy, and Overall Accuracy. These metrics provide a critical, quantitative benchmark for comparing different remote sensing products, classification algorithms, or ecological models, guiding scientists toward the most reliable data products for their work [9].

Core Accuracy Metrics and Their Calculation

The confusion matrix is the foundational tool from which all key accuracy metrics are calculated. It is a square table that cross-tabulates the class labels derived from a remote sensing classification against the reference labels obtained from validation data [30]. The following diagram illustrates the workflow for creating a confusion matrix and deriving the core accuracy metrics.

Deconstructing the Confusion Matrix

Consider a simplified ecological classification map that categorizes land cover into three classes: Forest, Water, and Grassland. A confusion matrix summarizing its performance against 230 validation points might look like this:

Table 1: Example Confusion Matrix for a Land Cover Classification

| Classification | Forest | Water | Grassland | Bare Soil | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forest | 56 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 62 |

| Water | 1 | 67 | 1 | 0 | 69 |

| Grassland | 5 | 0 | 34 | 7 | 46 |

| Bare Soil | 2 | 0 | 9 | 42 | 53 |

| Total | 64 | 67 | 48 | 51 | 230 |

In this matrix [30]:

- Rows represent the class labels from the map classification.

- Columns represent the class labels from the reference (validation) data.

- The diagonal cells (from top-left to bottom-right) show the number of correctly classified pixels for each class.

- Off-diagonal cells show misclassifications. For instance, 4 pixels that were truly "Grassland" were misclassified as "Forest."

Calculating the Key Metrics

From the confusion matrix, the three core accuracy metrics are calculated as follows:

Table 2: Formulas and Interpretation of Core Accuracy Metrics

| Metric | Formula | Interpretation | Question it Answers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Accuracy | (Sum of Diagonal Cells / Total Samples) × 100% |

The overall probability that a pixel on the map has been correctly classified. | "What proportion of the entire map is correct?" |

| User's Accuracy (UA) | (Diagonal Cell / Row Total) × 100% |

The probability that a pixel labeled as Class X on the map is actually Class X on the ground. | "If I use this map and find a pixel of Class X, how likely is it to be correct?" |

| Producer's Accuracy (PA) | (Diagonal Cell / Column Total) × 100% |

The probability that a pixel of Class X on the ground is correctly shown as Class X on the map. | "If a field site is truly Class X, how likely is the map to have captured it correctly?" |

Applying the Formulas to the Example Matrix:

- Overall Accuracy = (56 + 67 + 34 + 42) / 230 = 199 / 230 = 86.5%

- User's Accuracy for Grassland = (34 / 46) × 100% = 73.9%

- Producer's Accuracy for Grassland = (34 / 48) × 100% = 70.8%

These metrics reveal a nuanced story. While the overall accuracy of 86.5% might seem high, the User's and Producer's accuracies for Grassland are significantly lower. This indicates specific confusion between Grassland and other classes, which could be critical for an ecologist studying grassland habitats [30].

Experimental Protocols for Accuracy Assessment

A robust accuracy assessment requires a carefully designed validation protocol. The goal is to collect reference data that provides an unbiased estimate of the map's error.

Validation Data Collection Workflow

The following diagram outlines the key stages in designing and executing a robust accuracy assessment.

Detailed Methodologies

1. Defining Validation Data and Sampling Design: The reference dataset must be independent of the data used to train the classification algorithm [30]. To avoid bias, a probability-based sampling design is essential. The most recommended approach is stratified random sampling, where the map itself is used to define strata (the classes), and a random sample of pixels is selected within each stratum [9] [22]. This ensures that even rare classes are sufficiently represented in the validation set. Sample size is critical; a common rule of thumb is to collect a minimum of 50-100 samples per class, though this can vary with project scope and complexity [30].

2. Data Collection and Practical Considerations: Reference data can be collected through:

- Field observation: The gold standard, involving GPS and photography to document land cover at specific coordinates. The spatial unit observed must be consistent with the map's spatial resolution (e.g., documenting the dominant land cover in a 30x30 meter area for a Landsat pixel) [30].

- High-resolution imagery: Visual interpretation of imagery from sources like Google Earth or drones is a cost-effective alternative when field access is limited [30]. Key considerations include ensuring that class definitions are consistent between the map and reference data, and that the timing of reference collection aligns with the date of the remote sensing imagery to account for seasonal or land cover changes [30].

Comparative Analysis of Accuracy Assessment Practices

Understanding the theoretical metrics is only the first step. It is equally important to contextualize them within the actual reporting practices of the scientific community.

Current Reporting Trends and Reproducibility

A comprehensive review of 282 peer-reviewed papers on land and benthic cover mapping published between 1998 and 2017 revealed significant gaps in reporting standards [22]. The results highlight a critical need for more rigorous and transparent accuracy reporting.

Table 3: Reporting Trends in Remote Sensing Accuracy Assessment (n=282 papers)

| Reporting Element | Frequency | Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Included an Error Matrix | 56% | Without the full matrix, User's and Producer's accuracy cannot be calculated, limiting the utility of the assessment. |

| Reported Overall Accuracy with Confidence Intervals | 14% | The vast majority of studies fail to communicate the precision of their accuracy estimate. |

| Used Kappa Coefficient | 50.4% (post-2012) | Continued use of a metric that is increasingly criticized as redundant and based on incorrect assumptions [22]. |

| Used Probability-Based Sampling | 54% | Nearly half of all studies may have used potentially biased sampling methods for validation. |

| Assessment Deemed Fully Reproducible | 32% | Only about one-third of studies provided a complete and transparent methodology (error matrix, probability sampling, and dataset characterization) [22]. |

Impact of Map Accuracy on Area Estimation

Accuracy metrics are not just quality indicators; they have direct practical consequences. When a classification map is used to estimate the area of a land cover class (e.g., total forest cover), the simple method of counting pixels is biased due to omission and commission errors [9]. A more statistically sound approach is to use the map for stratification and then estimate areas from the reference data collected via a probability sample.

In this context, map accuracy impacts efficiency. A more accurate map will lead to more precise area estimates, meaning a smaller sample size is required to achieve a target variance, or conversely, a fixed sample size will yield an estimate with improved precision [9]. The impact of User's and Producer's accuracy on this efficiency is non-linear and depends on the target class. For rare classes, Producer's Accuracy has a greater impact on efficiency, while User's Accuracy becomes more influential as the target class proportion increases [9].

This section details the key "research reagents" and tools required for conducting a rigorous accuracy assessment in remote sensing ecology.

Table 4: Essential Resources for Accuracy Assessment

| Tool / Resource | Function in Accuracy Assessment | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Data | Serves as the "ground truth" benchmark against which the map is compared. | Field GPS data, high-resolution aerial photos, commercial satellite imagery (e.g., Planet), Google Earth. |

| Sampling Design Protocol | Provides a statistical framework for selecting validation points to ensure an unbiased estimate. | Stratified random sampling is the recommended standard [9] [30]. |

| Error Matrix Software | Automates the calculation of accuracy metrics from paired classification and reference data. | Functions in R (caret package), Python (scikit-learn), GIS software (ArcGIS, QGIS). |

| Spatial Analysis Platform | The computational environment for overlaying reference points on the classified map and extracting values. | Google Earth Engine [10], QGIS, ArcGIS Pro, ERDAS IMAGINE. |

| High-Resolution Imagery | Acts as a source for reference data collection when field work is not feasible. | Aerial photography, satellite data from WorldView, Pleiades, or SkySat [30]. |

| Visualization Tools | Creates clear charts and graphs to communicate accuracy results effectively. | Charting libraries (Matplotlib, ggplot2), dedicated tools like ChartExpo [36]. |

Calculating User's, Producer's, and Overall Accuracy is a fundamental practice for validating remote sensing products used in ecological research. These metrics, derived from the confusion matrix, provide a nuanced understanding of a classification's strengths and weaknesses that a single overall accuracy value cannot. However, the value of these metrics is entirely dependent on the rigor of the underlying validation protocol, which must be based on an independent, probability-sampled reference dataset.

The remote sensing community has established clear best practices, yet widespread adoption remains a challenge, with many published studies lacking fully reproducible accuracy assessments [22]. For the research scientist, insisting on this level of transparency is crucial. When evaluating a remote sensing product for use in drug development research or ecological modeling, the presence of a complete error matrix and a clear description of the sampling methodology is the best indicator of a reliable and trustworthy data source. By applying these rigorous assessment standards, researchers can make informed decisions, minimize uncertainty in their analyses, and build their work upon a foundation of quantitatively validated spatial data.

In the evolving landscape of ecological research, the assessment of environmental quality increasingly hinges on the sophisticated integration of disparate data sources. The fundamental challenge facing researchers and scientists lies in reconciling the expansive coverage of remote sensing technologies with the granular accuracy of ground-based monitoring methods. Remote sensing offers unprecedented spatial and temporal coverage, with satellite constellations now capable of monitoring over 90% of global agricultural land, while traditional ground monitoring provides validated, high-precision measurements crucial for calibration and validation [5]. This integration is not merely technical but conceptual, requiring frameworks that can accommodate data from fundamentally different observational perspectives.

The imperative for multi-source data integration stems from the complex, multi-factorial nature of ecological systems. Single-source data, whether from satellite platforms or field sensors, inevitably presents an incomplete picture, potentially leading to flawed conclusions in critical areas such as climate impact assessment, biodiversity monitoring, and environmental quality evaluation. Advances in machine learning frameworks have dramatically transformed this landscape, enabling researchers to build models that can learn from and make predictions based on heterogeneous datasets that vary in scale, format, and underlying measurement principles [37] [38]. This capability is particularly valuable in ecological research, where understanding the relationship between remote sensing observations and ground-based measurements forms the foundation of accurate environmental assessment.

Comparative Analysis of Monitoring Approaches: Remote Sensing vs. Ground-Based Methods

The choice between remote sensing and ground-based monitoring methods represents a fundamental trade-off between spatial coverage and measurement precision. Understanding this balance is crucial for designing effective ecological research strategies and interpreting results accurately.

Technical Capabilities and Performance Metrics

Table 1: Performance comparison between InSAR remote sensing and traditional ground monitoring methods for ecological applications.

| Evaluation Criteria | InSAR (Remote Sensing) | Traditional Ground Monitoring |

|---|---|---|

| Monitoring Technique | Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar, Satellite/Aerial Remote Sensing | Manual Surveying, Sensors, LiDAR, GPR, Visual Inspection |

| Technology Used | Radar Phase Analysis, AI Algorithms | Physical Instruments/Sensors, Optical & Laser Scanning |

| Spatial Resolution | ~10-100 m (2025 Typical) | Centimeter-level (Localized); Limited Area |

| Temporal Frequency | Daily/Weekly (Estimated), Continuous for Many Areas | Biweekly to Monthly (Estimated); Point in Time |

| Data Accuracy | 85%-95% (Large Scale Deformation Tracking) | 98%+ (Localized Parameters) |

| Area Coverage | Thousands of km² Per Pass; >90% Global Ag Land | 10–100 km² Max (Per Operation); 30–40% Global Ag Land |

| Cost Efficiency | $2–$10/km² (Subscription/Platform-Based) | $50–$500/km² (Manual, Labor, Equipment) |

| Implementation Time | 1–2 weeks (Digital Deployment) | 4–12 weeks (Fieldwork Planning & Labor) |

| Key Strength | Broad, preventive, proactive management | Detailed on-site actions; underlying diagnosis |

As evidenced in Table 1, InSAR technology demonstrates particular strength in detecting subtle ground movements with millimeter-level precision across vast geographical areas, making it invaluable for monitoring phenomena such as land subsidence from groundwater extraction or pre-landslide warning signs in forested areas [5]. This capability is enhanced by its weather-agnostic operation, as radar penetrates cloud cover to ensure consistent data collection regardless of atmospheric conditions. The technology's capacity to monitor "inaccessible or dangerous terrain" further extends its utility in ecological research where field access is challenging or hazardous [5].

Conversely, traditional ground monitoring excels in providing highly accurate, localized measurements essential for validating remote sensing data and understanding mechanistic processes. Techniques such as soil sampling, ground-penetrating radar (GPR), and in-situ sensors deliver precise measurements of parameters including soil moisture, temperature, nutrient levels, and compaction that remote sensing can only infer indirectly [5]. These methods form the critical "ground truth" against which remote sensing classifications are validated, serving as an accuracy standard in assessment procedures [30] [21]. The limitations of ground-based approaches primarily relate to their constrained spatial coverage and labor-intensive implementation, which often restricts sampling to a small fraction of large or difficult-to-access areas.

Accuracy Assessment Frameworks

The integration of remote sensing and ground-based data necessitates rigorous accuracy assessment protocols. The standard methodology involves creating a confusion matrix (also called an error matrix or contingency table) that compares classified remote sensing data against validation data collected from field observations [30] [21]. This comparison enables the calculation of three key accuracy metrics:

- User Accuracy: Answers the question "If I have your map, and I go to a pixel that your map shows as class 'x', how likely am I to actually find class 'x' there?" [30]

- Producer Accuracy: Addresses "If an area is actually class 'x', how likely is it to also have been mapped as such?" [30]

- Overall Accuracy: Represents the proportion of the map that is correctly classified [30].

Critical to a valid assessment is the creation of appropriate validation data that covers all land cover classes in the map, is distributed randomly or evenly throughout the study area, and contains sufficient data points per class to be statistically representative [30]. This process requires careful attention to matching class definitions between the classification and validation data, while considering the spatial resolution of the remote sensing imagery to ensure comparable ground observations.

Machine Learning Frameworks for Multi-Source Data Integration

The complexity of integrating multi-source ecological data has driven the development of specialized machine learning frameworks designed to handle disparate data types, scales, and structures. These frameworks provide the computational foundation for building predictive models that leverage both remote sensing and ground-based data sources.

Comparative Framework Analysis

Table 2: Comparison of selected machine learning frameworks suitable for multi-source ecological data integration.

| Framework | Ease of Use | Coding Required | Team Size | Key Strength | Ecological Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TensorFlow | Intermediate | High | Medium/Large | End-to-end platform with deployment support | Large-scale land cover classification and change detection [39] [40] |

| PyTorch | Intermediate | High | Medium/Large | Dynamic computation graph for research flexibility | Experimental neural network designs for habitat mapping [39] [40] |

| Scikit-learn | Easy | Moderate | Small/Medium | Classical ML algorithms for structured data | Predictive modeling with integrated environmental variables [39] [40] |

| Amazon SageMaker | Intermediate | Moderate | Large | Fully managed service for building, training, deployment | Cloud-based processing of satellite imagery streams [39] [40] |

| H2O | Intermediate | Moderate | Medium/Large | Distributed computing for big data | Risk and fraud trend analysis in environmental compliance [39] |

| LangChain/LangGraph | Advanced | High | Medium/Large | Experimental flexibility for complex workflows | Multi-model comparison for ecological forecasting [41] |

| AutoGen | Advanced | High | Medium/Large | Collaborative multi-agent systems | Complex experimental designs with specialized model components [41] |

Specialized Frameworks for Ecological Applications

Beyond general-purpose machine learning frameworks, several specialized approaches have demonstrated particular utility for ecological data integration:

The CA-Markov (Cellular Automata-Markov) model integrates remote sensing data with historical trends to predict ecological changes. This combined approach utilizes the spatial simulation capabilities of Cellular Automata with the temporal projection strength of Markov chains, enabling researchers to forecast ecological quality based on multi-temporal remote sensing data [10]. In one application, this framework achieved a training accuracy of 95.24% with field validation reaching 98.33% for mapping oak-dominated forest habitats [12].

Stacking fusion models represent another advanced approach, combining multiple machine learning algorithms (e.g., RandomForest, LightGBM, and CatBoost) to enhance prediction accuracy. Research on predicting greenhouse tomato crop water requirements demonstrated that a stacking model outperformed individual algorithms and other fusion approaches, achieving the lowest prediction errors across multiple metrics [38]. This approach comprehensively considered "various factors, including environmental, soil, and crop growth conditions" that influence crop water requirements [38].

Experimental Protocols for Framework Evaluation

Robust experimental design is essential for evaluating the performance of integrated data frameworks in ecological research. The following protocols provide methodological guidance for assessing framework effectiveness.

Multi-Source Data Integration Protocol

The integration of parking occupancy, pedestrian, weather, and traffic data for on-street parking prediction offers a transferable protocol for ecological applications. This approach involved:

- Data Collection: Gathering four distinct datasets (parking occupancy, pedestrian volume, traffic flow, and weather conditions) from public sources in the City of Melbourne [37].

- Relationship Analysis: Investigating the correlation between primary data (parking occupancy) and external factors (pedestrian volume, traffic flow, weather conditions) to determine their predictive relevance [37].

- Model Comparison: Implementing multiple machine learning algorithms (Multilayer Perceptron (MLP), Random Forest (RF), Decision Trees (DT), K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Gradient Boosting (GA), Adaptive Boosting (AB), and linear SVC) to identify the best-performing approach [37].

- Real-time Deployment: Implementing the best-performing model for real-time prediction with evaluation of ingest rates (0.1 events per second) and throughput (0.3 events per second) to assess operational feasibility [37].