Bridging the Gap: How Integrated Remote Sensing and Ground-Based Technologies Are Revolutionizing Drug Development

This article explores the transformative integration of remote sensing and ground-based technologies in biomedical research and drug development.

Bridging the Gap: How Integrated Remote Sensing and Ground-Based Technologies Are Revolutionizing Drug Development

Abstract

This article explores the transformative integration of remote sensing and ground-based technologies in biomedical research and drug development. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it provides a comprehensive analysis spanning from foundational principles and methodological applications to troubleshooting and validation frameworks. By synthesizing the latest advancements, this article serves as a strategic guide for leveraging these synergistic technologies to enhance data collection, improve clinical trial efficiency, and unlock novel digital biomarkers for a new era of decentralized, data-driven medicine.

The New Frontier: Foundational Concepts and Exploratory Potential of Integrated Sensing

The integration of remote sensing and ground-based technologies represents a paradigm shift in environmental monitoring, ecological research, and precision agriculture. This synergy addresses the limitations inherent in using either approach in isolation, creating a unified framework that leverages the macroscopic, continuous coverage of remote sensing with the precise, localized detail of terrestrial measurements [1] [2]. The core principle of this integration is not merely the simultaneous use of disparate datasets, but their fusion into a coherent, multi-scale information system that provides insights unattainable by any single method [3]. This approach is revolutionizing our ability to map forest habitats with high accuracy, monitor grassland ecosystems, manage agricultural resources with precision, and predict severe weather events [1] [3] [4]. By bridging the gap between the macroscopic and the microscopic, this integrated framework is becoming indispensable for addressing complex challenges related to climate change, biodiversity conservation, and sustainable resource management [1] [5].

Core Integration Principles and Theoretical Framework

The effective integration of remote and ground-based data is governed by several foundational principles. These principles ensure that the combined data streams produce valid, reliable, and actionable information.

The Four-Pillar Taxonomic Framework

A comprehensive framework for understanding sensor integration organizes technologies into four complementary pillars based on their measurement principles and applications [3]:

- Structural Sensors: Technologies such as LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) and GNSS Interferometric Reflectometry (GNSS-IR) that capture the three-dimensional physical structure of the environment, including vegetation height, canopy architecture, and topography.

- Spectral Sensors: Instruments including multispectral, hyperspectral, and near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) that measure the interaction of electromagnetic radiation with surface materials, enabling the assessment of biochemical properties like chlorophyll content, water stress, and soil composition.

- Quantum Sensor Technologies: Emerging approaches such as Cosmic-Ray Neutron Sensing (CRNS) and neutron probes that utilize quantum phenomena to measure soil moisture and other environmental variables over large areas.

- Proximal/Physiological Sensors: Ground-based devices like thermal sensors, electrochemical sensors, and Leaf Area Index (LAI) analyzers that provide direct, high-frequency measurements of plant physiological status and immediate environmental conditions.

The synergistic potential of these pillars is unlocked when they are integrated with remote sensing platforms, model-data assimilation techniques, and digital platforms for decision support [3].

Methodological Levels of Data Fusion

Integration occurs at three primary methodological levels, each with distinct processes and outcomes [2]:

- Pixel-Based Fusion: This low-level fusion combines raw data from different sensors at the pixel level to create a new, synthesized image with enhanced properties, such as improved spatial resolution. For example, blending high-resolution panchromatic satellite data with lower-resolution multispectral data.

- Feature-Based Fusion: This intermediate level involves extracting distinctive features (e.g., texture, shape, or vegetation indices) from different data sources and then combining these features for tasks like classification or target detection.

- Decision-Based Fusion: This high-level fusion involves combining the interpreted results or decisions from multiple algorithms or sensors. Each sensor's data is processed independently, and the final decision is made based on a consensus or weighted combination of these individual outputs.

Application Notes: Quantitative Synergies in Practice

The theoretical principles of integration are demonstrated and validated through concrete applications across diverse fields. The quantitative benefits of this synergy are evident in the enhanced accuracy and capabilities reported in recent studies.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance of Integrated Technology Applications

| Application Domain | Integrated Technologies | Key Performance Metric | Result | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forest Habitat Mapping | Ground phytosociological data + Sentinel-2 multispectral data + Deep Learning (Natural Numerical Network) | Field Validation Accuracy | 98.33% accuracy in mapping oak-dominated habitats | [1] |

| Precipitation Estimation | GPM Satellite DPR + X-band Phased Array Radar (XPAR) + Ground Observations | Correlation Coefficient (vs. Ground Truth) | GPM: 0.66XPAR: ~0.88 | [4] |

| Precision Agriculture | UAS + Satellite Imagery (data fusion) | General Capability Enhancement | Enhanced spatial resolution, improved biomass estimation, and refined crop type mapping | [2] |

Protocol: Integrated Forest Habitat Mapping and Monitoring

Objective: To accurately map and monitor protected forest habitats within a defined network (e.g., Natura 2000) by integrating ground-based ecological surveys with satellite remote sensing and deep learning.

Materials and Reagents:

- NaturaSat Software or equivalent geospatial analysis platform.

- Sentinel-2 Satellite Imagery providing multispectral data (e.g., Visible, NIR, SWIR bands).

- Ground Data: GPS unit, field sheets, and equipment for phytosociological relevés (species inventory, canopy cover estimation, etc.).

- Computing Environment: Hardware/software capable of running deep learning algorithms (e.g., Python with TensorFlow/PyTorch).

Experimental Workflow:

- Ground-Based Data Collection: Conduct phytosociological surveys at pre-determined sample plots within the forest area. Precisely record species composition, abundance, diameter at breast height (DBH), and other structural parameters. Record the GPS coordinates of each plot.

- Remote Sensing Data Acquisition: Download a time series of Sentinel-2 imagery covering the study area. The imagery should span multiple seasons to capture phenological variations critical for distinguishing habitats.

- Automated Segmentation and Dataset Creation: Using software like NaturaSat, perform automated image segmentation based on the coordinates of the ground surveys. This creates a dataset where each segment is linked to its ground-measured ecological characteristics.

- Algorithm Training: Train a deep learning algorithm (e.g., a Convolutional Neural Network) on the created dataset. The model learns to associate specific spectral and temporal signatures from the satellite imagery with the forest habitats defined by the ground data.

- Prediction Map Generation and Validation: Deploy the trained model to generate a habitat prediction map (relevancy map) for the entire study area. Validate the map's accuracy through field visits to randomly generated locations not used in the training process [1].

Protocol: Synergistic Precipitation Estimation for Extreme Weather

Objective: To achieve high-accuracy, high-temporal-resolution quantitative precipitation estimation (QPE) for improved detection and early warning of heavy rainfall events by fusing space-borne and ground-based radar data.

Materials and Reagents:

- X-band Phased Array Weather Radar (XPAR) data for high-resolution local monitoring.

- Global Precipitation Measurement (GPM) Satellite Dual-frequency Precipitation Radar (DPR) data for broad three-dimensional precipitation structure.

- Ground Rain Gauge observations for calibration and validation.

- Data Processing Software with capabilities for geospatial interpolation and radar data analysis.

Experimental Workflow:

- Multi-Source Data Acquisition: Collect concurrent data streams from the XPAR, the GPM satellite overpasses, and a network of ground-based rain gauges for a specific precipitation event.

- Data Pre-processing and Calibration: Independently calibrate the XPAR and GPM DPR data using the ground rain gauge measurements as a reference. Apply necessary corrections for attenuation and other artifacts.

- Data Fusion via Interpolation and Calibration: Fuse the GPM and XPAR datasets by employing detailed interpolation and calibration methods. The high-resolution XPAR data serves to downscale and correct the broader-scale GPM observations, creating a unified precipitation field.

- Product Generation and Validation: Generate a high-resolution, high-accuracy quantitative precipitation estimate product. Validate the fused product against a separate set of ground observations, calculating performance metrics like Correlation Coefficient, Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Technologies

Successful integration relies on a suite of essential technologies and platforms that serve as the fundamental "reagents" for research in this field.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Integration Studies

| Item Name | Category | Primary Function | Key Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sentinel-2 Satellite Constellation | Space-based Platform / Spectral Sensor | Provides free, multi-temporal multispectral imagery with global coverage. | Baseline land cover monitoring, vegetation index calculation (NDVI), and change detection [1] [3]. |

| Unmanned Aerial System (UAS) | Airborne Platform | Carries various sensors (optical, multispectral, LiDAR) for very high-resolution, on-demand data collection. | Bridging the scale gap between satellites and ground plots; detailed crop monitoring and precision agriculture [2]. |

| Phased-Array Weather Radar (XPAR) | Ground-based Platform / Structural Sensor | Enables rapid scanning (under 1 min) of the atmosphere for detailed analysis of severe convective weather. | High-temporal-resolution precipitation estimation and storm microphysics analysis [4]. |

| Cosmic-Ray Neutron Sensor (CRNS) | Quantum Sensor | Measures field-scale soil moisture by detecting low-energy neutrons produced by cosmic rays. | Providing integrated soil moisture data for hydrology and agriculture, complementing point measurements and remote sensing [3]. |

| Geographic Information System (GIS) | Data Analysis Platform | Manages, analyzes, models, and visualizes spatial and attribute data from multiple sources. | The central hub for data integration, spatial analysis, and map production [6]. |

| Deep Learning Algorithms (e.g., CNN) | Analytical Tool | Automates complex pattern recognition in large, multi-dimensional datasets (e.g., image classification). | Creating predictive maps of habitats or crop types from fused satellite and ground data [1] [2]. |

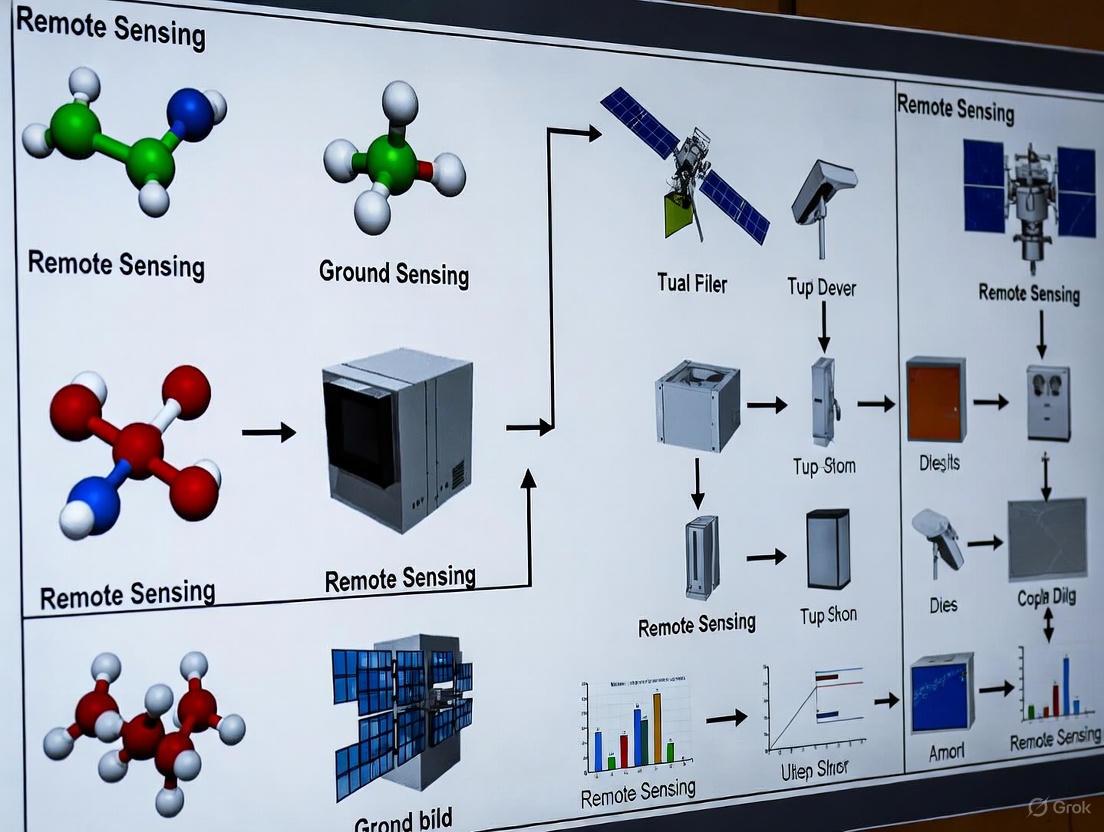

Integrated Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and synergistic relationship between remote sensing and ground-based technologies in a typical environmental monitoring application.

Data Integration Workflow - This diagram illustrates the synergistic flow from multi-source data acquisition through fusion to final insights, including critical calibration feedback loops.

The integration of remote sensing and ground-based technologies is founded on the core principles of multi-scale observation, synergistic data fusion, and continuous validation. By systematically applying the frameworks, protocols, and tools outlined in this article, researchers and scientists can overcome the inherent limitations of any single data source. The result is a transformative capability to monitor complex environmental systems with unprecedented accuracy, efficiency, and depth, thereby providing a robust scientific basis for addressing some of the most pressing ecological and climatic challenges of our time. The future of this field lies in the continued refinement of fusion algorithms, the incorporation of emerging quantum-based sensors, and the seamless integration of these multi-source data streams into digital platforms for real-time decision support [3] [2].

The convergence of Decentralized Clinical Trials (DCTs) and digital biomarkers is revolutionizing drug development. This transformation, accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic, shifts clinical research from site-centric models to patient-focused approaches that leverage digital health technologies (DHTs) [7]. DCTs are operational models where some or all trial activities occur at or near the participant's home, facilitated by technologies and innovative operational approaches to data collection [8]. Simultaneously, digital biomarkers—objectively measured, collected, and interpreted through DHTs—provide continuous, real-world insights into patient health and treatment response [9]. This integration addresses long-standing challenges in traditional trials, including participant burden, lack of diversity, and intermittent data collection, thereby creating more efficient, inclusive, and evidence-driven pathways for therapeutic development [8] [7].

Quantitative Landscape of DCT and Digital Biomarker Adoption

The adoption of DCTs and digital biomarkers has demonstrated significant growth, though penetration varies across regions and therapeutic areas. The following tables summarize key quantitative findings from recent surveys and study analyses.

Table 1: Adoption Patterns and Perceived Benefits of DCTs and Remote Data Capture (Based on a Survey of 80 Indian Clinical Research Stakeholders) [10]

| Survey Metric | Response Data | Additional Context |

|---|---|---|

| Experience with DCTs | 67% of respondents reported <25% of their trials were decentralized; none reported 100% decentralization. | Indicates a predominant hybrid trial model, blending traditional and decentralized elements. |

| Prior Experience with RDC/Wearables | 50% had some prior experience, mainly with RDC implementation in clinical trials. | 40% had implemented RDC in observational studies. |

| Common RDC Methods | 59% indicated wearables/devices were the most common method. | Wrist-worn wearables were the most frequently used type. |

| Key Benefits | >90% cited access to real-time data and insights; 69% noted time savings and convenience for site staff. | 60% and 55% reported convenience for patients and sponsors, respectively. |

| Probability of Near-Future Use | Weighted average score of 2.83 (on a 1-5 scale) for probability of using RDC in DCTs in the next 6-12 months. | 56% of respondents did not answer this question. |

Table 2: Analysis of Decentralized Clinical Trial Case Studies [7]

| Trial Characteristic | Findings from 23 Analyzed Case Studies |

|---|---|

| Initiation Trend | The first recorded DCT was initiated in 2011 (the REMOTE trial), with the majority of identified DCTs starting between 2020 and 2022. |

| Trial Status | Studies were categorized as Completed (13), Ongoing (3), Recruiting (2), Terminated (3), and Enrollment by Invitation (1). |

| Scale of Enrollment | Enrollments ranged from single-digit figures to over 49,000 participants, demonstrating applicability across small and large-scale studies. |

| Primary Rationale for Decentralization | Categorized as by necessity (e.g., during pandemic), for operational benefits, to address unique research questions, or for endpoint/platform validation. |

Application Notes & Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Implementing a Hybrid Decentralized Clinical Trial

Aim: To outline a standardized procedure for deploying a hybrid DCT that integrates remote data capture and digital biomarkers for a chronic condition study (e.g., hypertension or diabetes).

Background: Hybrid DCTs mitigate participant burden while maintaining scientific rigor and data integrity, which are susceptible to fraud and sampling bias in fully remote settings [11].

Step 1: Protocol Feasibility and Technology Selection

- Technology Assessment: Identify and validate DHTs (e.g., FDA-cleared wearable sensors, smartphone apps) suitable for the therapeutic area. Key selection criteria include:

- Technical: Sensor accuracy, battery life, data sampling frequency, and compatibility with various smartphone models [12].

- Patient-Centric: Ease of use, comfort, hypoallergenic materials, multi-language support, and minimal charging requirements [12].

- Operational: Secure, cloud-based data infrastructure capable of handling continuous data streams from thousands of devices simultaneously [12].

- Regulatory and Ethics Preparation: Prepare documentation for IRB/Ethics Committee submission, including data security plans, privacy safeguards per GDPR/HIPAA, and patient-facing materials for remote informed consent [8] [9].

- Technology Assessment: Identify and validate DHTs (e.g., FDA-cleared wearable sensors, smartphone apps) suitable for the therapeutic area. Key selection criteria include:

Step 2: Participant Enrollment and Integrity Assurance

- Remote Screening & Consent: Utilize electronic consent (eConsent) platforms with integrated identity verification features, such as video capture [11].

- Fraud Mitigation: Implement automated tools like CheatBlocker to screen for duplicate or fraudulent enrollment attempts in real-time [11].

- Representative Sampling: Deploy quota management tools like QuotaConfig to set and monitor enrollment targets for key demographics (e.g., age, sex, race, disease severity) to ensure a representative study population [11].

Step 3: Remote Trial Execution and Data Collection

- Kit Logistics & Training: Ship pre-configured device kits (e.g., wearable sensor, blood pressure cuff) directly to participants. Include pictorial guides and access to instructional videos.

- Biomarker Data Capture: Use an integrated data capture platform (e.g., MyTrials app) to streamline the collection of multiple data types into a single system (e.g., REDCap) [11].

- Site Support & Monitoring: Provide site staff with remote access to dashboards showing participant adherence and preliminary data trends to enable proactive intervention [12].

Step 4: Data Management, Analysis, and Closure

- Data Processing: Subject digital biomarker data to pre-processing pipelines for noise reduction, feature extraction (e.g., generating sleep measures from accelerometer data), and alignment with clinical events [9] [12].

- Statistical Analysis: Analyze data within the ICH E9(R1) estimand framework, defining how intercurrent events (e.g., device non-wear) will be handled statistically [7].

- Study Closure: Remote collection of endpoint data, device return via pre-paid mailers, and final data reconciliation.

Protocol for Validation of a Digital Biomarker

Aim: To establish a rigorous methodology for developing and validating a novel digital biomarker as a surrogate endpoint in a clinical trial.

Background: Digital biomarkers derived from sensors provide continuous, objective measurements but require robust validation to be considered regulatory-grade [9].

Step 1: Algorithm Development and Training

- Data Acquisition for Training: Collect high-frequency, raw sensor data (e.g., PPG, EDA, accelerometer) from a dedicated cohort of patients and healthy controls in a controlled setting [12].

- Feature Engineering & Model Training: Extract clinically relevant features from raw signals. Train machine learning (e.g., Random Forest) or deep learning models (e.g., Convolutional Neural Networks) to map sensor data to a clinical construct or established biomarker [13] [9].

- Bias Mitigation: Ensure the training dataset is demographically and clinically diverse to prevent algorithmic bias and improve generalizability [9].

Step 2: Analytical Validation

- Precision & Repeatability: Assess the algorithm's performance in terms of test-retest reliability and technical variability under controlled conditions.

- Accuracy vs. Gold Standard: Compare the digital biomarker's readings against a clinically accepted reference standard (e.g., polysomnography for sleep biomarkers, clinician-administered scales for motor symptoms) [9].

Step 3: Clinical Validation

- Context of Use: Define the specific clinical context (e.g., "detection of motor fluctuations in Parkinson's disease").

- Correlation with Clinical Endpoints: In a targeted clinical study, demonstrate a strong correlation between the digital biomarker and the primary clinical outcome of interest.

- Sensitivity to Change: Establish that the digital biomarker can detect statistically significant, clinically meaningful changes over time or in response to an intervention [9].

Step 4: Regulatory Submission and Real-World Performance

Integrated Workflow and System Architecture

The successful implementation of DCTs with digital biomarkers relies on a cohesive integration of patient-facing, operational, and analytical components. The following diagram illustrates the end-to-end architecture.

DCT System Data Flow

The validation and application of digital biomarkers follow a structured pathway from signal acquisition to regulatory-grade evidence, as shown below.

Digital Biomarker Validation Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Technologies and Platforms for DCTs and Digital Biomarker Research

| Tool Category | Example Solutions | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Medical-Grade Wearable Platforms | EmbracePlus (Empatica) [12] | A versatile, FDA-cleared wearable with multiple sensors (PPG, EDA, Accelerometer, etc.) for continuous raw data and digital biomarker collection in clinical trials. |

| Remote Data Capture & eConsent | MyTrials App [11], REDCap Integrated Tools | Smartphone applications and web-based systems to streamline remote collection of patient-reported outcomes, vital signs, and electronic consent. |

| Data Integrity & Fraud Prevention | CheatBlocker [11] | An automated tool integrated with REDCap to detect and prevent duplicate or fraudulent screening submissions in DCTs. |

| Representative Sampling Management | QuotaConfig [11] | A real-time monitoring tool to ensure enrolled participant samples meet pre-specified demographic and clinical criteria, countering selection bias. |

| Cloud Data Integration & APIs | Empatica Cloud API [12] | Allows seamless integration of wearable sensor data into existing Clinical Trial Management Systems (CTMS) and sponsor data platforms. |

| Digital Biomarker Algorithms | Proprietary or Partner Algorithms (e.g., from DoMore Diagnostics [13]) | AI/ML models that transform raw sensor data into validated, clinically meaningful digital endpoints (e.g., Histotype Px for cancer prognosis). |

Application Notes

The global remote sensing data analysis market is projected to grow from USD 21.64 billion in 2025 to USD 47.24 billion by 2032, representing a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 11.8% [14]. This growth is fueled by the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML), which enables more precise and rapid data interpretation. Advancements in sensor technologies and the proliferation of small satellites (CubeSats) are simultaneously reducing costs and increasing data accessibility [14]. Remote sensing has become a critical tool for decision-making across commercial and governmental domains, supporting applications from environmental monitoring to urban planning and defense.

Table 1: Global Remote Sensing Data Analysis Market Forecast (2025-2032)

| Metric | 2025 Value | 2032 Value | CAGR (2025-2032) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Market Size | USD 21.64 Billion | USD 47.24 Billion | 11.8% |

Table 2: Key Market Segment Shares in 2025

| Segment | Dominated By | 2025 Market Share |

|---|---|---|

| Sensing Technology | Passive Sensing | 61.2% |

| Service Type | Data Acquisition & Processing | 49.4% |

| Geographic Region | North America | 49.4% |

Core Component 1: Sensors

Sensors are the foundational hardware that collect information about an object or phenomenon without direct physical contact [15]. They are broadly classified based on their source of illumination.

1.2.1. Passive Sensors rely on natural energy sources, such as sunlight reflected or emitted from the Earth's surface [16] [17]. They dominate the market due to their cost-effectiveness and broad application spectrum [14].

- Principle: Detect reflected solar radiation or naturally emitted thermal radiation [18].

- Key Types:

- Radiometers: Measure the intensity of electromagnetic radiation [17].

- Spectrometers/Spectroradiometers: Designed to detect, measure, and analyze the spectral content of reflected electromagnetic radiation [17]. Hyperspectral radiometers capture data in hundreds of narrow, contiguous spectral bands for detailed material identification [16].

- Imaging Radiometers: Capture images while measuring radiation to create detailed maps [16].

- Advantages: Lower power requirements, proven technology, rich historical data archives.

- Limitations: Dependent on sunlight, cannot penetrate dense cloud cover, ineffective at night [16] [17].

1.2.2. Active Sensors provide their own source of illumination, emitting signals toward a target and measuring the energy that returns [16] [17].

- Principle: Emit energy (e.g., laser pulses, microwave radiation) and measure the signal's backscatter and time delay [18].

- Key Types:

- Radar (Radio Detection and Ranging): Uses microwave signals to measure distance and map terrain. It is all-weather capable [16].

- LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging): Uses laser pulses to create high-resolution digital elevation models (DEMs) and measure vegetation structure [16] [15].

- Laser Altimeters: A type of LiDAR used specifically for precise elevation measurement [16].

- Scatterometers: Measure backscattered radiation to study surface roughness, such as ocean winds [16].

- Advantages: Operate independently of sunlight and time of day, can penetrate clouds and rain (microwave), and provide direct ranging information [16].

Table 3: Comparison of Active and Passive Sensing Technologies

| Feature | Active Sensing | Passive Sensing |

|---|---|---|

| Energy Source | Own source (sensor-emitted) | External source (e.g., sunlight) |

| All-Weather Capability | High (Microwave) | Low (blocked by clouds) |

| Day/Night Operation | Yes | Limited to daytime (optical) |

| Example Technologies | Radar, LiDAR, Scatterometer | Multispectral Imager, Radiometer |

| Primary Applications | Topographic mapping, elevation models, ocean wind | Vegetation health, land surface temperature |

Core Component 2: Data Transmission

The volume of data acquired by modern remote sensing satellites far exceeds the downlink capacity of direct satellite-to-ground links, creating a significant data transmission bottleneck [19]. For example, the ratio of data acquisition rate to data transfer back rate can be as low as 0.086 (e.g., GeoEye-1 satellite), meaning less than 10% of the collected data can be transmitted back in a timely manner using a single link [19].

1.3.1. Transmission Strategies and Platforms

- Low-Earth Orbit (LEO) Satellites: Orbit from 160 to 2,000 km above Earth. They offer high-resolution data but have short communication windows (typically 10-15 minutes) with any single ground station [17] [19].

- Geostationary Orbit (GEO) Satellites: Orbit at 35,786 km, maintaining a fixed position relative to the Earth. They provide near-continuous coverage but typically offer coarser spatial resolution [17].

- Multi-Layer Satellite Networks: Advanced strategies use GEO satellites as relay nodes to offload data from LEO satellites. This extends the transmission window for LEOs, as the GEO link to Earth is almost always available [19].

- Inter-Satellite Links (ISL): Enable data routing between satellites to reach a ground station with available capacity [19].

1.3.2. Innovative Transmission Protocols A proposed strategy to overcome the downlink bottleneck involves a two-phase transmission scheme combining LEO-to-Earth Station (LEO-ES) links and GEO offloading under dynamic topology [19].

- Phase 1: Initial Data Allocation: Data on an LEO satellite is divided into reserved data (for direct transmission via LEO-ES links) and offloaded data (to be sent to a GEO relay).

- Phase 2: GEO Resource Allocation: A Two-Way Bargaining Game Scheme under Dynamic Topology (TWBGS-DT) uses a Stackelberg game model to optimally allocate the GEO satellite's cache space among multiple LEOs, maximizing the total volume of data offloaded [19].

The diagram below illustrates this integrated data transmission workflow.

Core Component 3: Analysis Platforms

Once data is transmitted to Earth, analysis platforms are required to process raw data into actionable information. The integration of AI, particularly ML and DL, has revolutionized this stage [20].

1.4.1. Software Platforms

- Google Earth Engine (GEE): A cloud-based platform providing access to a massive catalog of satellite imagery and geospatial datasets. It enables large-scale analysis using Google's computational infrastructure, supporting both JavaScript and Python APIs [21].

- QGIS: A free, open-source Geographic Information System (GIS) with robust remote sensing capabilities. Its functionality can be extended with plugins like the Semi-Automatic Classification Plugin (SCP) and Orfeo Toolbox (OTB), which offer ML-based image classification [21].

- ENVI: A specialized software for processing and analyzing geospatial imagery, excelling in multispectral and hyperspectral image analysis, atmospheric correction, and change detection [21].

- ArcGIS Insights: Integrates spatial and non-spatial data for comprehensive analysis, providing advanced spatial, statistical, and predictive modeling capabilities [21].

- eCognition: Utilizes an object-based image analysis (OBIA) approach, segmenting images into objects before classifying them, which is often more effective than pixel-based methods for high-resolution imagery [21].

1.4.2. AI and Machine Learning Integration AI-powered models have dramatically enhanced the automation, speed, and accuracy of remote sensing data interpretation [14] [20].

- Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs): Excell in image classification, object detection, and segmentation by extracting spatial features from imagery [20].

- Random Forests (RFs): An ensemble ML method widely used for land cover classification and change detection [21] [20].

- Support Vector Machines (SVM): Effective for classification tasks, particularly with high-dimensional data [21] [20].

- Real-World Application: Planet Labs uses AI-powered change detection systems to monitor deforestation in the Amazon, automatically identifying illegal logging activities [14].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: AI-Driven Land Cover Classification and Change Detection

This protocol details a methodology for using AI to classify land cover and detect changes over time, applicable to environmental monitoring and urban planning.

2.1.1. Research Reagent Solutions Table 4: Essential Materials and Software for AI-Based Land Cover Classification

| Item | Function/Description | Example Tools |

|---|---|---|

| Satellite Imagery Data | Primary input data for analysis. | Sentinel-2, Landsat 8/9 [21] |

| Cloud Computing Platform | Provides computational power and data catalog for large-scale processing. | Google Earth Engine (GEE) [21] |

| Machine Learning Library | Provides algorithms for training classification models. | Scikit-Learn (in QGIS/EnMAP-Box) [21] |

| GIS/Remote Sensing Software | Platform for data visualization, pre-processing, and analysis. | QGIS, ArcGIS, ENVI [21] |

| Training Dataset | Ground truth data for training and validating the ML model. | Manually labeled data, existing land cover products [20] |

2.1.2. Methodology

- Data Acquisition and Pre-processing:

- Select a study area and time period.

- Access a multi-temporal stack of satellite images (e.g., from Sentinel-2) via GEE or another platform.

- Perform atmospheric correction to convert raw digital numbers to surface reflectance values.

- Compute relevant spectral indices (e.g., NDVI for vegetation, NDWI for water) to enhance features.

Training Data Preparation:

- Define land cover classes of interest (e.g., Urban, Forest, Water, Agriculture).

- Manually collect sample points (polygons) for each class across the imagery, using high-resolution basemaps or field data for reference. Split the samples into training and validation sets (e.g., 70%/30%).

Model Training:

- Extract spectral and index values from the imagery at each sample point location.

- Train a classifier, such as a Random Forest model, using the training data. The model learns the spectral "signature" of each land cover class.

Classification and Validation:

- Apply the trained model to the entire image to generate a land cover map.

- Use the reserved validation samples to assess accuracy. Calculate metrics like Overall Accuracy and Kappa Coefficient [20].

Change Detection:

- Repeat the classification process for imagery from a different date.

- Compare the two classified maps to identify pixels that have changed from one class to another (e.g., Forest to Urban).

- Quantify the area and rate of change for each transition.

The workflow for this protocol is summarized in the diagram below.

Protocol: Near-Real-Time Flood Mapping with SAR Data

This protocol leverages active microwave sensing (SAR) for rapid flood inundation mapping, which is critical for disaster response, as SAR can penetrate clouds and operate day or night [16] [20].

2.1.1. Research Reagent Solutions

- SAR Imagery: Satellite-based Synthetic Aperture Radar data (e.g., from Sentinel-1).

- Processing Software: Software with SAR processing capabilities (e.g., SNAP, ENVI, GEE).

- Classification Algorithm: A model to distinguish water from land.

2.1.2. Methodology

- Data Selection: Acquire a pre-flood (reference) and a post-flood Sentinel-1 SAR image covering the area of interest.

- Pre-processing: Perform standard SAR pre-processing steps including radiometric calibration, speckle filtering, and terrain correction.

- Feature Extraction: Calculate key parameters such as:

- VV/VH Backscatter Intensity: Water bodies typically exhibit very low backscatter, appearing dark in SAR images.

- Interferometric Coherence: Measures the change in the scattering properties between two acquisitions. A sharp drop in coherence often indicates inundation.

- Classification: Input the extracted features into a Random Forest classifier to accurately delineate flooded pixels from non-flooded ones [20]. The integration of VV coherence and amplitude has been shown to improve accuracy by up to 50% while reducing computational time by 35% [20].

- Validation and Dissemination: Validate the flood map with ground reports or optical imagery (where cloud-free). The final map can be distributed to emergency response teams.

The convergence of small satellites, artificial intelligence (AI), and real-time data processing is fundamentally transforming remote sensing and ground-based technology integration. This paradigm shift enables a move from traditional, delayed data collection and analysis to a dynamic, intelligent, and responsive Earth observation framework. The core of this transformation lies in the deployment of proliferated small satellite constellations in Low Earth Orbit (LEO), which provide unprecedented temporal resolution and global coverage. When integrated with advanced AI algorithms, these systems can process and interpret vast streams of geospatial data directly in orbit, turning raw pixels into actionable intelligence in near-real time. This integrated capability is critical for a wide range of applications, from defense and maritime security to environmental monitoring and disaster management, supporting timely decision-making for researchers, government agencies, and commercial entities [22] [23].

The Small Satellite Market Landscape

The foundation of this new remote sensing paradigm is the rapidly expanding small satellite market. Characterized by satellites with a mass of less than 500 kg, this sector is experiencing explosive growth, driven by lower costs, rapid technological advancement, and increased launch activity.

Market Size and Growth Projections

Recent market analyses reveal a consistent and robust upward trajectory for small satellites, albeit with varying projections due to different methodological approaches. The table below consolidates key market data from multiple industry reports for easy comparison.

Table 1: Small Satellite Market Size and Growth Projections

| Source | Market Size (2024) | Projected Market Size (2032-2034) | Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) | Forecast Period |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNS Insider [24] | USD 6.05 billion | USD 20.58 billion by 2032 | 16.58% | 2025-2032 |

| Global Market Insights [25] | USD 6.9 billion | USD 30.6 billion by 2034 | 16.4% | 2025-2034 |

| Fortune Business Insights [26] | USD 11.41 billion | USD 19.67 billion by 2032 | 4.8% | 2025-2032 |

This growth is fueled by several key factors: the proliferation of private space companies, technological miniaturization, and the rising demand for satellite-based services such as broadband communication and Earth observation [25] [26]. As of March 2025, small satellites constituted approximately 61.5% of all active satellites in space, underscoring their dominance in the new space economy [25].

Segmentation and Key Trends

The market's dynamics are further clarified by analyzing key segments, including satellite type, application, and orbit.

Table 2: Small Satellite Market Segmentation and Leading Trends

| Segmentation Criteria | Dominant Segment | Key Trend / Fastest-Growing Segment | Driver |

|---|---|---|---|

| Satellite Type | MiniSats (100-500 kg) [24] | NanoSats (1-10 kg) [25] [24] | Lower cost, shorter development cycles, suitability for rideshare launches [25] [24]. |

| Application | Communication [24] | Communication [26] [24] | Demand for global broadband (e.g., Starlink, OneWeb) [26] [24]. |

| End User | Commercial [24] | Government & Military [25] [24] | Demand for tactical intelligence, surveillance, and secure communications [25] [24]. |

| Orbit | Low Earth Orbit (LEO) [24] | Low Earth Orbit (LEO) [24] | Proximity to Earth for low-latency communications and monitoring [25] [24]. |

A critical enabler of this growth is the shift towards mass production and advanced manufacturing. Companies are establishing automated production lines to meet demand; for instance, Azista BST Aerospace aims to produce two satellites per week from its facility in India [26]. Furthermore, advanced manufacturing techniques like 3D printing are revolutionizing production by enabling lightweight, complex components and reducing both time and cost [26] [23].

Artificial Intelligence in Remote Sensing

Artificial Intelligence, particularly deep learning, serves as the analytical brain of modern remote sensing, unlocking the value within massive and complex datasets.

AI Applications and Methodologies

AI algorithms are being deployed for a wide range of analytical tasks, transforming raw sensor data into actionable information.

Table 3: Key AI Applications and Methodologies in Remote Sensing

| Application Domain | AI Methodology | Protocol / Function | Use Case Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Image Classification & Object Detection | Deep Learning (e.g., Convolutional Neural Networks) | Training models on labeled datasets to identify and classify features like buildings, vessels, and land cover [27] [28]. | Automated building footprint extraction from aerial imagery for urban planning [28]. |

| Data Fusion | Multi-sensor fusion algorithms | Integrating data from Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR), Electro-Optical (EO), and Radio Frequency (RF) sensors to create a verified, 360-degree picture [22]. | Fusing SAR and AIS data to detect "dark vessels" that have disabled their tracking transponders [22]. |

| Anomaly & Change Detection | Behavioral analytics and pattern recognition | Identifying deviations from established patterns or norms across temporal image series [22]. | Detecting illegal fishing activities through anomalous vessel movement patterns [22]. |

| Onboard Autonomous Targeting | Onboard AI processors with specialized algorithms | Enabling satellites to analyze imagery in real-time and autonomously decide to retask sensors for specific phenomena [29]. | NASA's Dynamic Targeting technology autonomously avoiding clouds or targeting wildfires [29]. |

The integration of AI with Geographic Information Systems (GIS), often termed GeoAI, is a particularly powerful trend. It allows for the spatial validation, enrichment, and visualization of AI-derived insights, embedding them directly into a geographic context for more effective decision-making [28] [30].

Protocol: Automated Feature Extraction Using Deep Learning

The following protocol details a standard methodology for using deep learning to extract building footprints from high-resolution optical imagery, a common task in geospatial analysis [28].

Application Note: This protocol is designed for use with high-resolution (e.g., 16 cm) orthophotography and requires a GIS software platform with deep learning capabilities (e.g., ArcGIS Pro with its bundled Python environment).

Procedure:

- Training Data Preparation:

- Inputs: Select a representative sample area of your orthophotography and obtain corresponding, accurately digitized building footprint polygons for that area.

- Label Dataset Creation: Use the building footprint polygons to create a classified raster image, also known as a label dataset. This raster will have a uniform value for pixels representing buildings and a different value for the background.

- Export Training Chips: Use a geoprocessing tool (e.g.,

Export Training Data for Deep Learning) to generate many small image chips from the orthophoto, paired with their corresponding labeled segments from the label dataset.

Model Training:

- Input: The image chips and labels exported in Step 1.

- Process: Train a deep learning model (e.g., a U-Net or other suitable convolutional neural network) using the image chips. The model learns the spectral and spatial characteristics of buildings.

- Output: A trained model file (e.g., an Esri Model Definition

.emdfile).

Inference (Prediction):

- Input: The trained model from Step 2 and a new, larger orthophoto of the area of interest.

- Process: Run a geoprocessing tool (e.g.,

Classify Pixels using Deep Learning) on the new imagery. The model analyzes the image and produces a new raster where each pixel is classified as "building" or "not building."

Post-Processing:

- Vectorization: Convert the resulting classified raster into polygon features using a tool like

Raster to Polygon. - Regularization: The initial polygons will be rough and pixelated. Use a regularization tool (e.g.,

Regularize Building Footprint) to smooth edges, right-angle corners, and create cartographically clean building polygons.

- Vectorization: Convert the resulting classified raster into polygon features using a tool like

The workflow for this protocol is visualized below.

Diagram 1: Deep Learning Feature Extraction Workflow

Real-Time Onboard Data Processing

The ultimate frontier in remote sensing is moving data analysis from the ground to the satellite itself, enabling immediate response to dynamic events.

Concepts and Enabling Technologies

Onboard AI Processing: This involves equipping satellites with specialized, radiation-hardened AI processors capable of running machine learning models directly in orbit. This eliminates the latency of downlinking terabytes of raw data for ground-based analysis [29] [31]. For example, NASA's Dynamic Targeting flight test on the CogniSAT-6 CubeSat used an onboard AI processor from Ubotica to analyze look-ahead imagery for clouds and make targeting decisions within 60-90 seconds [29].

Real-Time Scheduling in LEO Networks: The dynamic nature of large LEO constellations requires sophisticated algorithms to manage computing and communication resources. Research from the Singapore University of Technology and Design (SUTD) has developed novel graph-based algorithms to address this:

- k-shortest path-based (KSP) Method: Prioritizes communication, finding efficient data paths before checking for computing resources.

- Computing-aware shortest path (CASP) Method: Prioritizes scarce computing resources, then finds the best communication paths to them. These algorithms are essential for supporting real-time applications like environmental monitoring and object tracking across a shifting satellite network [31].

Protocol: Autonomous Satellite Targeting for Event Detection

This protocol outlines the methodology for autonomous satellite retasking, as demonstrated by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory [29].

Application Note: This protocol is designed for satellites equipped with an agile platform, a look-ahead imaging capability (either via a dedicated sensor or by tilting the satellite), and an onboard AI processor.

Procedure:

- Look-Ahead Image Acquisition:

- The satellite tilts forward along its orbital path to acquire imagery of the upcoming ground area. (On CogniSAT-6, this was a 40-50 degree tilt.)

Onboard AI Analysis:

- The look-ahead imagery is routed to the onboard AI processor.

- A pre-trained, specialized algorithm (e.g., for cloud detection, wildfire identification, or plume detection) analyzes the imagery in real-time.

Autonomous Decision Making:

- Based on the algorithm's output, the satellite's planning software makes a decision.

- For cloud avoidance: If the look-ahead scene is cloudy, it cancels the planned imaging activity. If it is clear, it proceeds.

- For event detection: If a target of interest (e.g., a fire) is identified, the software calculates the optimal pointing for the main sensor to observe it.

Sensor Tasking and Execution:

- The satellite tilts back to the calculated position (e.g., nadir for a clear scene, or a specific off-nadir angle for a detected event).

- The main high-resolution sensor is tasked to capture the imagery, ensuring data collection is focused only on valuable, cloud-free, or event-specific targets.

The logical flow of this autonomous decision-making process is as follows.

Diagram 2: Autonomous Satellite Targeting Logic

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

For researchers developing and working with integrated small satellite and AI systems, the following table details essential "research reagents" – the critical hardware, software, and data components.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Satellite AI and Real-Time Processing

| Research Reagent | Type | Function / Application | Exemplars / Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Onboard AI Processor | Hardware | Enables real-time inference and analysis directly on the satellite, reducing latency and data downlink volume. | Processors used in projects like NASA's Dynamic Targeting (e.g., Ubotica) [29]. |

| Small Satellite Platform | Hardware | The physical satellite bus, providing power, propulsion, and payload hosting. | CubeSats, NanoSats, MicroSats from providers like Planet Labs, Terra Orbital, NanoAvionics [25] [24]. |

| Multi-Sensor Payloads | Hardware | Provides diverse data inputs for fusion and analysis. | Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR), Electro-Optical (EO), and Radio Frequency (RF) sensors [22] [27]. |

| GeoAI Software Toolkits | Software | Integrates AI with geospatial analysis for model training, inference, and spatial validation of results. | ArcGIS API for Python with arcgis.learn module, GeoAI toolboxes in commercial GIS software [28] [30]. |

| Temporal Graph Algorithms | Algorithm | Manages and schedules computing/communication resources in dynamic, large-scale LEO satellite networks. | k-shortest path (KSP) and computing-aware shortest path (CASP) methods [31]. |

| Labeled Geospatial Datasets | Data | Used for training and validating deep learning models for tasks like object detection and land cover classification. | Public (e.g., NASA ESDS) or commercial satellite imagery with corresponding feature labels (e.g., building footprints) [27] [28]. |

| Electric Propulsion Systems | Hardware | Provides efficient propulsion for small satellites, enabling orbital maneuvering and extending mission lifespan. | Technological advancements highlighted as a key trend in satellite development [25] [26]. |

The integration of small satellites, artificial intelligence, and real-time processing is not an incremental improvement but a revolutionary leap for remote sensing and ground-based technology integration. The landscape in 2025 is defined by a rapidly growing small satellite ecosystem, sophisticated AI-driven analytical pipelines, and the emerging capability for autonomous, intelligent response from orbit. For researchers and professionals, this convergence opens new frontiers for scientific discovery, operational efficiency, and rapid response to global challenges. The protocols and tools detailed in this application note provide a foundational roadmap for engaging with this dynamic and transformative field.

From Theory to Practice: Methodological Frameworks and Real-World Applications

Standardized Frameworks for Seamless DHT Integration in Clinical Investigations

The integration of Digital Health Technologies (DHTs) in clinical investigations represents a paradigm shift in data collection methodologies, mirroring advancements in remote sensing for environmental and agricultural monitoring. Just as remote sensing technologies leverage satellite and aerial platforms to capture geospatial data without direct physical contact [20], DHTs enable the collection of physiological and behavioral data from clinical trial participants beyond traditional clinical settings. This convergence of ground-based sensing (via wearable sensors) and remote monitoring principles creates unprecedented opportunities for continuous, objective data acquisition in clinical research [32] [33]. The fundamental paradigm connects established remote sensing methodologies with emerging digital clinical applications, establishing a technological continuum from environmental monitoring to human biometric assessment.

The adoption of DHTs in clinical trials has grown significantly due to their ability to provide richer datasets through continuous monitoring in a participant's natural environment [32] [33]. This approach reduces recall bias that flaws Patient Reported Outcomes and provides objective measurements that enhance understanding of intervention efficacy and safety [32]. Regulatory bodies including the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Medicines Agency (EMA) have recognized DHT potential, establishing frameworks and committees to support implementation [32]. The recent qualification of digital endpoints such as stride velocity 95th centile for ambulatory Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy studies by EMA demonstrates the growing regulatory acceptance of DHT-derived endpoints in drug development [32].

Core Framework: V3+ for DHT Validation

The V3+ framework provides a comprehensive, modular approach to ensure DHTs are fit-for-purpose and generate reliable, clinically meaningful data [34]. This structured validation methodology comprises four core components: verification, analytical validation, clinical validation, and usability validation, with the "+" representing crucial additional considerations including security and economic feasibility [34].

Table 1: The V3+ Framework Components for DHT Validation

| Component | Purpose | Key Activities | Output Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Verification | Confirm DHT meets technical specifications | Engineering tests, performance validation | Accuracy (±5%), Reliability (<0.1% failure rate), Consistency (low variability) [34] |

| Analytical Validation | Ensure algorithms accurately interpret sensor data | Algorithm comparison to gold standards, statistical validation | Correlation coefficients, sensitivity/specificity, algorithm performance metrics [34] |

| Clinical Validation | Establish clinical relevance and utility | Clinical studies in target population, outcome measures assessment | Clinical accuracy, relevance to disease state, correlation with clinical outcomes [34] |

| Usability Validation | Ensure intuitive use and minimal burden | Human factors testing, formative and summative evaluations | User error rates, task completion times, satisfaction scores [34] |

The modularity of V3+ represents one of its most powerful attributes, allowing each component to be independently updated or revised as technology evolves [34]. This flexibility accommodates rapid technological advancements without necessitating complete re-evaluation, saving significant time and resources while maintaining rigorous standards [34]. For instance, if a sensor-based DHT undergoes a hardware improvement that affects its technical specifications but not its clinical application, only the verification component would require re-assessment, while clinical validation findings would remain applicable.

Experimental Protocol: Implementing DHTs in Clinical Trials

Pre-Implementation Planning and Feasibility Assessment

Successful DHT integration begins with comprehensive pre-implementation planning. The first critical step involves defining the Concept of Interest (CoI) - the health experience meaningful to patients that represents the intended treatment benefit [32]. Subsequently, researchers must establish the Context of Use (CoU), specifying how the DHT will be deployed within the trial, including endpoint hierarchy, patient population, and study design [32]. This foundation informs the development of a conceptual framework that visualizes relevant patient experiences, targeted concepts, and how proposed endpoints fit within the overall clinical trial assessment strategy [32].

Device selection follows a rigorous assessment process to ensure fitness-for-purpose. Sponsors should evaluate manufacturer capabilities including data security, privacy measures, scalability, financial stability, and global logistical support [33]. This includes assessing the manufacturer's ability to provide devices appropriate for diverse patient populations (e.g., varying arm circumferences for blood pressure cuffs) and ensuring adequate technical support infrastructure [33]. Furthermore, manufacturers must supply comprehensive validation/verification reports and all applicable regulatory approvals (e.g., FDA 510(k) clearance, EU CE Certification) [32].

Implementation and Data Collection Workflow

The implementation phase requires meticulous attention to training, data collection protocols, and patient safety monitoring. Training must be timely and tailored to end-users (both site staff and patients), with materials available in appropriate languages and formats [33]. Psychometric analysis of training materials can gauge comprehension and compliance likelihood [33]. Efficient 24/7 local language support is essential for addressing technical issues promptly [33].

Data collection strategies should balance comprehensiveness with patient burden. Passive data collection approaches are preferred when possible to minimize participant effort, particularly in populations with physical or cognitive limitations [33]. For example, in oncology studies with participants having limited life expectancy, manually intensive data collection protocols may be inappropriate [33]. Data transfer mechanisms should be designed for minimal patient effort, with automatic edit checks implemented at point of collection to ensure data quality [33].

Throughout implementation, patient safety remains paramount. Sponsors must establish key metrics early in trial planning, including thresholds for acceptable data quantity, parameter ranges that trigger health reviews, and compliance metrics to identify re-training needs [33]. Robust data privacy and security measures must align with regulatory requirements and Good Clinical Practice guidelines [33].

Diagram 1: DHT Implementation Workflow in Clinical Trials - This diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for implementing Digital Health Technologies in clinical investigations, spanning pre-implementation planning, validation, and trial execution phases.

Data Management and Analysis Framework

Holistic Data Processing Pipeline

The volume and complexity of DHT-derived data necessitate sophisticated data management strategies. A single study with hundreds to thousands of patients can generate millions of data points, creating both opportunities for deep insights and challenges for processing and analysis [33]. A holistic approach encompasses data cleaning, aggregation, and analysis with robust automated systems.

Data cleaning requires built-in automatic edit checks at multiple levels, including:

- Data entry validation (both initial site entry and subsequent patient entries from home)

- Demographic discrepancy checks (accounting for device-specific requirements)

- Physiological plausibility checks (identifying absurd values based on known physiological parameters) [33]

Data aggregation must address time-synchronization across multiple devices and geographical locations, accounting for time zones and daylight saving time variations [33]. Conversion into standardized formats compatible with downstream analytical needs is essential, particularly when combining data from multiple sources (e.g., integrating dose administration timing with physiological measurements) [33].

Statistical Considerations and Endpoint Qualification

DHT-derived endpoints present unique statistical challenges that differ from traditional clinical endpoints. Regulatory acceptance requires demonstration of clinical meaningfulness - that changes in the digital endpoint reflect meaningful changes in the patient's health status [32]. This is particularly challenging for abstract concepts such as cognitive domains, where establishing clinical significance can be complex [32].

Regulators have emphasized that sensitivity to detect change alone is insufficient; the clinical interpretation of any effects on the instrument must be clear [32]. For example, in Alzheimer's Disease trials, regulators have noted challenges in interpreting clinical significance of effects on digital cognitive assessments, even when those instruments demonstrate sensitivity to subtle changes [32]. Early health authority consultations are advisable to ensure endpoint acceptance [32].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for DHT Implementation

| Category | Specific Tools/Solutions | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Validation Frameworks | V3+ Framework, EVIDENCE Checklist | Provide structured approach for DHT verification, analytical/clinical validation, and usability testing [34] |

| Data Management Platforms | Device-agnostic software with eSource integration | Enable electronic source data capture, eliminate manual data entry, reduce administrative burden [33] |

| Analytical Tools | Automated edit check systems, Time-synchronized aggregation algorithms | Ensure data quality through automated validation checks and synchronize data from multiple devices [33] |

| Regulatory Documentation | Pre-submission packages, Conceptual frameworks, Risk analysis reports | Support regulatory submissions by documenting context of use, validation evidence, and benefit-risk profile [32] |

| Training Resources | Multilingual instructional videos, Interactive simulations, Psychometrically validated materials | Ensure proper DHT use by sites and patients, maintain data quality through comprehensive training [33] |

Regulatory and Operational Considerations

Navigating Regulatory Requirements

Regulatory acceptance of DHT-derived endpoints is a rigorous, multifaceted process that requires evidence from multiple prospective studies to demonstrate validity, reliability, and clinical relevance [32]. Success depends on establishing a global strategy with early health authority consultations to ensure alignment with regulatory requirements [32]. The FDA's Framework for the Use of DHTs in Drug and Biological Product Development and the establishment of the DHT Steering Committee provide structured pathways for engagement [32].

When DHTs are used to capture novel endpoints addressing unmet measurement needs, sponsors must provide comprehensive evidence establishing:

- Content validity: The endpoint measures the intended concept and is meaningful to patients

- Reliability: Consistent results upon repeated measurement

- Ability to detect change: Sensitivity to meaningful clinical changes

- Clinical relevance: Association with important disease states or outcomes [32]

For DHTs that are medical devices, clearance/approval for the intended purpose significantly supports the case for being fit-for-purpose [32]. However, when the intended use differs from the manufacturer's claims, sponsors must perform gap analyses to determine what additional verification/validation studies are needed [32].

Operationalizing DHTs Across Therapeutic Areas

Therapeutic area-specific considerations significantly influence DHT implementation success. In respiratory diseases, while innovative technologies like impulse oscillometry technique or cough monitors seem attractive, regulatory acceptance remains limited for most digital endpoints [33]. Sponsors are currently advised to rely on established spirometry data while monitoring newer technologies as they approach regulatory acceptance [33].

In neurological disorders such as Alzheimer's Disease, establishing meaningfulness of digital cognitive assessments presents unique challenges, particularly when patients lack insight into their cognitive deficits [32]. Care partner input, while valuable, introduces subjectivity and may not accurately reflect the patient's experience [32].

Pediatric populations require special considerations for DHT implementation. Explaining device usage and ensuring compliance can be difficult with children, making reduced compliance a distinct possibility [33]. Alternative technologies that require less active participation (e.g., forced-oscillation technique versus traditional spirometry) should be considered when available and validated [33].

The integration of DHTs in clinical investigations represents a transformative advancement in clinical research methodology, enabling more continuous, objective, and patient-centered data collection. The standardized framework presented in this document provides a roadmap for successful implementation, from initial concept development through regulatory submission. As the field evolves, continued collaboration among sponsors, regulators, patients, and technology developers will be essential to refine these frameworks and realize the full potential of digital technologies to enhance drug development and patient care.

The parallels between remote sensing technologies and DHTs continue to strengthen, with both fields increasingly leveraging artificial intelligence and machine learning for data processing and analysis [20] [32]. As these technologies converge, lessons learned from one domain can inform advancement in the other, creating a virtuous cycle of innovation that benefits both environmental monitoring and human health assessment.

Data fusion in remote sensing refers to the theory, techniques, and tools for combining data from multiple sources to improve information quality, with the specific aim of achieving more reliable, accurate, and complete information than could be derived from any single data source alone [35]. The term "data fusion" emerged in the early 1970s during U.S. research on sonar signal understanding systems and later gained prominence through military command and control applications [35]. As remote sensing technologies have rapidly evolved, the availability of diverse sensor data has made fusion methodologies increasingly critical for extracting meaningful information from complex environmental systems.

In contemporary remote sensing, data fusion enables researchers to overcome the limitations of individual sensors by integrating complementary data characteristics. Multi-source remote sensing images capture the same ground objects but exhibit unique properties in reflecting target characteristics, providing information that is both complementary and synergistic [35]. This integration is particularly valuable in the context of integrating remote sensing with ground-based technologies, where different data sources contribute distinct aspects of information about phenomena under investigation. The fusion process spans multiple levels of abstraction, from raw data combination to feature integration and final decision synthesis, with each level offering distinct advantages for specific research applications.

Pixel-Level Fusion

Conceptual Foundation

Pixel-level fusion, also called data-level fusion, operates directly on raw sensor data to combine information from multiple sources at the most fundamental level [36] [37]. This approach processes the numerical values of each pixel from various images without prior feature extraction or interpretation [35]. By working with the original sensor measurements, pixel-level fusion preserves the fullest possible information content, maintaining fine details that might be lost at higher fusion levels [36]. This methodology is particularly valuable when researchers require maximum information retention from costly or difficult-to-acquire remote sensing data.

The technical implementation of pixel-level fusion requires precise registration of input images, as even minor misalignments can severely degrade fusion quality [36]. This registration process ensures that corresponding pixels in different images represent the same ground location, enabling meaningful mathematical operations between datasets. The fusion occurs before any significant information extraction, allowing the combined data to retain the original statistical properties and spatial relationships present in the source imagery [35]. This characteristic makes pixel-level fusion particularly suitable for applications requiring detailed spatial analysis and precise quantitative measurements.

Methodologies and Techniques

Intensity-Hue-Saturation (IHS) Transform: This color space transformation method separates spatial (intensity) and spectral (hue and saturation) information [35]. The intensity component from one image is replaced with that from another, followed by inverse transformation to create a fused image that combines the spatial detail of one dataset with the spectral characteristics of another. While effective for enhancing spatial resolution, IHS may cause significant spectral distortion, particularly in vegetation and water studies [35].

Principal Component Analysis (PCA): This statistical technique transforms correlated multispectral bands into uncorrelated principal components, with the first component containing the maximum variance [35]. The first principal component is replaced with a high-resolution panchromatic image before inverse transformation, effectively injecting spatial detail while preserving most spectral information. PCA-based fusion generally produces sharper images with better-maintained spectral characteristics compared to IHS methods [35].

Wavelet Transform: This multi-resolution analysis technique decomposes images into different frequency components [35]. The approximation and detail coefficients from different images are combined according to specific rules before reconstruction. Wavelet fusion effectively improves spatial resolution while maximizing spectral preservation and typically delivers superior signal-to-noise ratio performance compared to other pixel-level methods [35].

Brovey Transform: This computationally simple method uses a normalized multiplication of multispectral bands with a panchromatic band [35]. The technique sharpens images while largely preserving original spectral content, though some spectral distortion may occur, particularly in heterogeneous landscapes [35].

Table 1: Pixel-Level Fusion Methods Comparison

| Method | Key Principle | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| IHS Transform | Color space separation and replacement | Effective spatial enhancement, computationally efficient | Significant spectral distortion |

| PCA | Statistical transformation and component replacement | Better spectral preservation than IHS, good spatial enhancement | Complex implementation, may alter color relationships |

| Wavelet Transform | Multi-resolution coefficient combination | Excellent spectral preservation, improved signal-to-noise ratio | Computational complexity, parameter sensitivity |

| Brovey Transform | Normalized multiplicative sharpening | Computational simplicity, preserves spectral information | Limited to three bands, potential spectral distortion |

Experimental Protocol: Multi-Sensor Pixel Fusion

Objective: Fuse high-resolution panchromatic imagery with multispectral data to generate high-resolution multispectral output for detailed land cover analysis.

Materials and Equipment:

- High-spatial-resolution panchromatic image (e.g., 0.5-2m)

- Lower-spatial-resolution multispectral image (e.g., 10-30m)

- Image processing software (e.g., ENVI, ERDAS, or specialized MATLAB/Python tools)

- Sufficient computational resources (RAM ≥16GB, multi-core processor)

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Acquire temporally coincident panchromatic and multispectral imagery over the study area, ensuring minimal atmospheric interference.

- Preprocessing: Perform radiometric calibration and atmospheric correction on both datasets using established models (e.g., 6S, MODTRAN).

- Image Registration: Precisely co-register images to sub-pixel accuracy (RMSE <0.5 pixels) using polynomial transformation with nearest-neighbor resampling.

- Spatial Resampling: Resample multispectral data to match panchromatic pixel dimensions using cubic convolution.

- Fusion Process: Apply selected fusion algorithm (IHS, PCA, wavelet, or Brovey) with optimized parameters.

- Quality Assessment: Calculate quantitative metrics including correlation coefficient, root mean square error, and spectral angle mapper relative to reference data.

- Validation: Compare fused output with high-resolution multispectral ground truth data where available.

Applications: Pixel-level fusion has demonstrated particular value in multi-spectral and hyper-spectral image fusion to improve spatial resolution [36], medical imaging applications such as CT and MRI fusion for enhanced diagnostic information [36], and video surveillance systems that integrate multiple camera feeds to improve target detection and recognition capabilities [36].

Feature-Level Fusion

Conceptual Foundation

Feature-level fusion operates at an intermediate level of abstraction, where distinctive features are first extracted from each data source and subsequently integrated [36] [37]. This approach processes characteristics such as edges, textures, shapes, contours, and other salient patterns derived from the raw sensor data [35]. By working with extracted features rather than raw pixels, this methodology significantly reduces data volume while preserving the most semantically meaningful information [36]. The fusion occurs after feature extraction but before final decision-making, creating an information-rich representation that supports various classification and interpretation tasks.

The theoretical foundation of feature-level fusion rests on pattern recognition and machine learning principles, where features serve as discriminative descriptors that characterize objects or phenomena of interest [35]. This approach demonstrates particular strength in environments with varying noise conditions, as the feature extraction process can incorporate filtering mechanisms that improve robustness [36]. Additionally, feature-level fusion offers considerable flexibility by accommodating diverse feature types from heterogeneous sensors, including both handcrafted features (e.g., SIFT, HOG) and learned representations from deep architectures [36] [37].

Methodologies and Techniques

Principal Component Analysis (PCA): This dimensionality reduction technique transforms original features into a new orthogonal coordinate system where the greatest variance lies on the first coordinate [35]. The method effectively compresses feature information while minimizing redundancy, making it particularly valuable for handling high-dimensional remote sensing data. PCA-based feature fusion has demonstrated advantages in maintaining image clarity and computational efficiency compared to pixel-level approaches [35].

Sparse Representation (SR): This method models features using sparse linear combinations of basis elements from an over-complete dictionary [35]. The approach effectively captures intrinsic data structures and correlations between different feature types. While sparse representation can effectively model essential feature characteristics and inter-image relationships, it suffers from higher computational complexity compared to other feature fusion methods [35].

Neural Network Models: Both traditional Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) and modern Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) provide powerful frameworks for feature-level fusion [35]. ANNs implement adaptive pattern recognition through interconnected layers that can learn complex feature relationships [35]. CNNs leverage local connectivity to extract hierarchical spatial features, acquiring more complex structural information with greater robustness and efficiency [35]. The weight sharing strategy in CNNs dramatically reduces trainable parameters, enabling effective training with limited samples [35].

Clustering Analysis: This unsupervised approach groups similar features into clusters based on distance metrics in feature space [35]. The method effectively identifies natural groupings within data without requiring pre-labeled training examples, making it particularly valuable for exploratory analysis of novel remote sensing datasets.

Table 2: Feature-Level Fusion Methods Comparison

| Method | Key Principle | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Principal Component Analysis | Orthogonal transformation to reduce dimensionality | Effective compression, minimizes redundancy, maintains clarity | Linear assumptions, may lose nonlinear relationships |

| Sparse Representation | Linear combinations from over-complete dictionary | Captures intrinsic structures, models correlations | High computational complexity, parameter sensitivity |

| Neural Networks | Adaptive learning through interconnected layers | Powerful pattern recognition, handles complex relationships | Requires substantial training data, risk of overfitting |

| Clustering Analysis | Grouping by similarity in feature space | Unsupervised operation, identifies natural groupings | Distance metric sensitivity, cluster number determination |

Experimental Protocol: Multi-Modal Feature Fusion

Objective: Integrate features from hyperspectral imagery and LiDAR data to improve land cover classification accuracy in complex environments.

Materials and Equipment:

- Imaging spectrometer data (e.g., AVIRIS, HyMap, or PRISMA)

- Full-waveform or discrete-return LiDAR data

- Ground reference data for training and validation

- Computing environment with deep learning frameworks (e.g., TensorFlow, PyTorch)

Procedure:

- Feature Extraction:

- For hyperspectral data: Extract spectral features (absorption depths, continuum removal), spectral indices (NDVI, EVI), and texture measures (GLCM).

- For LiDAR data: Derive elevation models, intensity features, and structural metrics (canopy height, vertical distribution).

- Feature Normalization: Apply z-score standardization to all features to ensure comparable scales across modalities.

- Feature Selection: Implement sequential forward selection or random forests to identify the most discriminative feature subset.

- Feature Concatenation: Fuse selected features into a unified representation using early fusion (feature concatenation) or intermediate fusion (shared representations).

- Classifier Training: Train ensemble classifiers (random forests, gradient boosting) or deep neural networks on the fused feature set.