Beyond the Model: A Practical Guide to Validating Movement Ecology Approaches in Biomedical Research

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for the validation of movement ecology models.

Beyond the Model: A Practical Guide to Validating Movement Ecology Approaches in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for the validation of movement ecology models. It explores the foundational principles of key statistical models like Resource Selection Functions (RSF), Step Selection Functions (SSF), and Hidden Markov Models (HMMs), detailing their specific applications and assumptions. The content delivers actionable methodologies for implementation, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and presents a comparative analysis of validation techniques. By establishing rigorous 'evaludation' standards, this guide aims to enhance the credibility and predictive power of computational models, supporting their reliable integration into biomedical research and drug development pipelines.

Core Principles: Demystifying Movement Ecology Models and Their Role in Biomedical Science

Understanding the relationships between animal space use and the environment is a fundamental objective in ecological research and is essential for effective species conservation [1]. Statistical models that link animal movement data to environmental covariates provide critical insights into key ecological concepts such as habitat selection, movement corridors, and behavioral states [1]. Among the most prominent frameworks used for this purpose are Resource Selection Functions (RSF), Step Selection Functions (SSF), and Hidden Markov Models (HMMs). Each of these models operates on different principles, requires different data resolutions, and answers distinct ecological questions, making the choice of an appropriate method crucial for meaningful interpretation of results [1].

The proliferation of biologging devices has generated unprecedented volumes of movement data, creating a need for sophisticated analytical tools that can extract meaningful biological insights from complex, autocorrelated tracking data [2]. While RSFs and SSFs are both used to study habitat selection, they differ in their temporal resolution and how they account for movement constraints. HMMs, in contrast, represent a fundamentally different approach focused on identifying behavioral states and linking these states to environmental features [1] [3]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these three approaches, detailing their mathematical foundations, implementation requirements, and appropriate applications within movement ecology.

The table below provides a systematic comparison of the key characteristics of RSF, SSF, and HMM methodologies.

Table 1: Comparative overview of RSF, SSF, and HMM statistical models

| Feature | Resource Selection Function (RSF) | Step Selection Function (SSF) | Hidden Markov Model (HMM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Ecological Question | Broad-scale habitat selection; relative probability of use [1] | Small-scale habitat selection during movement; integrated movement & habitat selection [1] [3] | Behavioral state identification and state-dependent relationships with environment [1] [3] |

| Data Requirements | Animal locations (used) & random points (available) [1] | Observed steps & random steps from each relocation [4] | Regular time-series of movements (step lengths, turning angles) [3] |

| Temporal Resolution | Utilizes locations without strict sequence requirements [1] | Requires high-frequency, sequential relocation data [1] | Requires regular time-series data [3] |

| Handling of Autocorrelation | Often ignores temporal autocorrelation [1] | Explicitly accounts for movement autocorrelation by design [1] | Explicitly models autocorrelation as part of state process [3] |

| Key Output | Relative selection strength (coefficients) for habitat covariates [1] [4] | Selection coefficients for habitat covariates conditional on movement [4] | Behavioral state sequences & state-specific selection coefficients [3] |

| Mathematical Form | (w(\mathbf{x}) = \exp(\beta1 x1 + \beta2 x2 + \cdots + \betak xk)) [1] | Conditional logistic regression on observed vs. random steps [5] | (Pr(St=k \mid S{t-1}) ) & (Pr(Zt \mid St=k)) with state-specific (\beta_k) [3] |

| Implementation Scale | Home range (2nd order selection) or landscape (1st order) [1] | Within-home range movement (3rd order selection) [1] | Individual behavior with population-level inference possible [3] |

Detailed Model Methodologies

Resource Selection Function (RSF)

Experimental Protocol and Analysis The standard protocol for implementing an RSF involves several key stages. First, researchers define the availability domain, typically using the animal's home range estimated via methods like Minimum Convex Polygon (MCP) or Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) [1] [4]. Subsequently, observed "used" locations are compared to randomly sampled "available" locations within this domain. Environmental covariates such as elevation, vegetation type, or distance to human infrastructure are then extracted for both used and available points [4]. The final stage involves fitting a logistic regression model where the binary response variable indicates used (1) versus available (0) locations:

[ Pr(yi = 1|\mathbf{x}i) = \frac{\exp(\beta1 x{1,i} + \beta2 x{2,i} + \cdots + \betak x{k,i})}{1 + \exp(\beta1 x{1,i} + \beta2 x{2,i} + \cdots + \betak x{k,i})} ]

The exponential of the linear predictor, (w(\mathbf{x}) = \exp(\beta1 x1 + \beta2 x2 + \cdots + \betak xk)), provides the relative probability of selection, where positive coefficients indicate selection for a habitat feature and negative coefficients indicate avoidance [1] [4]. Model selection techniques like Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) can be used to compare different biological hypotheses represented by different covariate combinations [4].

Step Selection Function (SSF)

Experimental Protocol and Analysis SSF analysis requires a structured workflow to account for the sequential nature of movement data. The process begins with trajectory preprocessing, which involves constructing a regular time series of animal relocations, often requiring resampling to a consistent time interval (e.g., 10 minutes with a 2-minute tolerance) [6]. For each observed step (the vector between two consecutive locations), researchers generate a set of random steps that originate from the same starting point. These random steps represent alternative movement choices available to the animal at that moment [5].

The core analysis employs conditional logistic regression, where each stratum consists of one observed step and its associated random steps. This compares habitat characteristics along the observed path against what was available but unused, conditional on the animal's movement capabilities [5]. The model effectively decomposes into two components: a movement kernel that describes how animals move irrespective of habitat (using step lengths and turning angles) and a selection kernel that describes which habitats are selected once movement constraints are accounted for [3]. This framework directly integrates movement behavior with habitat selection, addressing a key limitation of traditional RSFs.

Hidden Markov Model (HMM)

Experimental Protocol and Analysis HMMs conceptualize animal movement as a doubly stochastic process comprising an observable sequence (movement metrics) and an underlying, unobserved sequence of behavioral states. The implementation protocol begins with data preparation, focusing on derived movement characteristics such as step lengths and turning angles, which serve as observed emissions [3]. The model is then defined by three core elements: the initial state probabilities (the probability of starting in each state), the state transition probability matrix (\gamma{ij} = \mathbb{P}(S{t+1} = j \mid S_t = i)), which defines the probability of switching from state i to state j, and the state-dependent distributions, which describe the probability of observing particular movement metrics (e.g., gamma-distributed step lengths) given the current behavioral state [3].

Model fitting typically employs the Expectation-Maximization algorithm, with the Baum-Welch algorithm being a specific variant for HMMs that estimates transition probabilities and emission distribution parameters [3]. After fitting, the Viterbi algorithm is used to decode the most likely sequence of hidden behavioral states given the observed data and model parameters. Advanced implementations such as HMM-SSF can integrate habitat selection directly into the state-dependent process, simultaneously identifying behavioral states and quantifying state-specific habitat selection [3] [5].

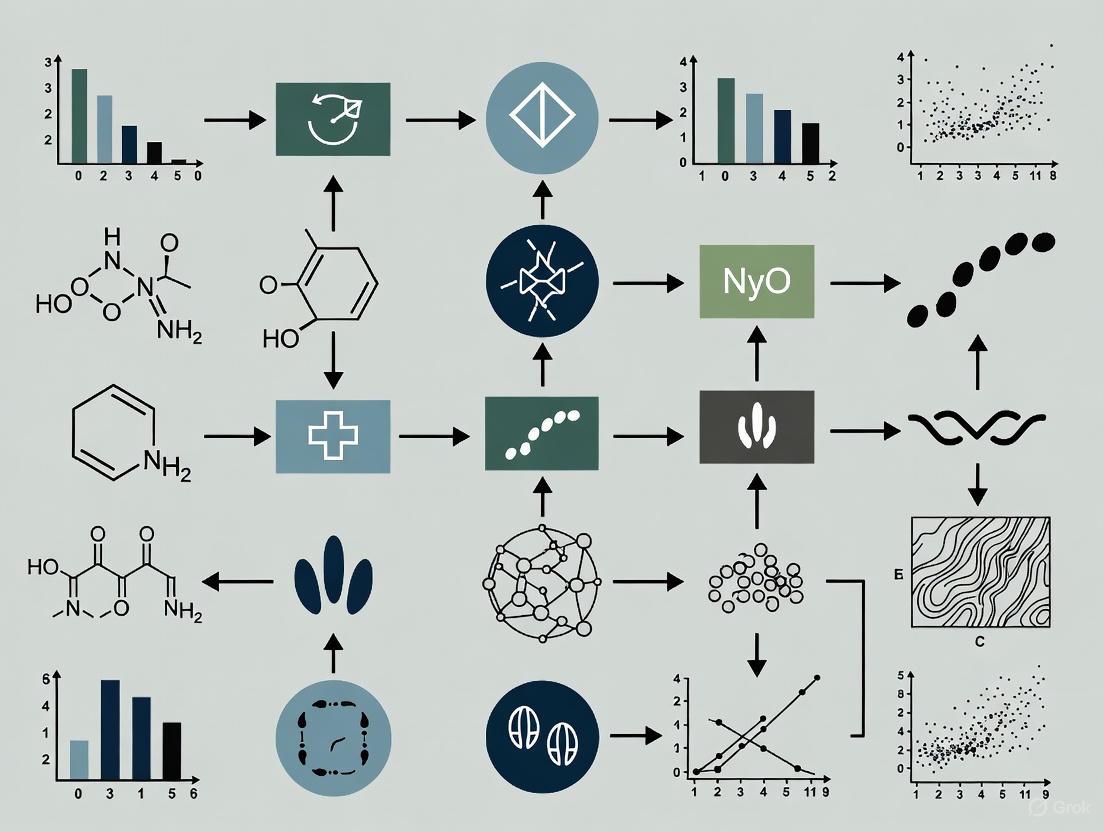

Workflow Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships and methodological flow between the three statistical models in movement ecology.

Research Toolkit

Table 2: Essential computational tools and reagents for movement ecology analysis

| Tool/Resource | Function/Purpose | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| R Statistical Software | Primary programming environment for statistical analysis and modeling | Comprehensive implementation of RSF, SSF, and HMM [1] [6] |

amt R Package |

Comprehensive toolkit for animal movement and habitat selection analysis | Creates tracks, generates random points/steps, extracts covariates, fits SSFs [1] [6] |

momentuHMM R Package |

Implements hidden Markov models for animal movement data | Fits multi-state HMMs with various observation distributions [1] |

glmmTMB R Package |

Fits generalized linear mixed models with Template Model Builder | Can implement weighted RSFs with random effects [6] |

| GPS Tracking Data | High-resolution animal relocation data | Typically requires resampling to regular intervals (e.g., 10 minutes) [6] |

| Environmental Covariates | Raster layers representing habitat characteristics | Elevation, vegetation, time since fire, distance to roads [1] [4] |

| Conditional Logistic Regression | Statistical method for matched case-control designs | Core statistical engine for SSF analysis [5] |

RSF, SSF, and HMM approaches offer complementary perspectives for understanding animal movement and habitat relationships, each with distinct strengths and appropriate applications. RSFs provide a robust framework for identifying broad-scale habitat selection patterns, while SSFs integrate movement constraints to reveal fine-scale habitat selection during locomotion. HMMs focus primarily on identifying behavioral states and quantifying how habitat associations vary with these states. The emerging framework of HMM-SSF represents a promising integration that simultaneously identifies behavioral states and state-specific habitat selection [3] [5].

Choosing the appropriate model requires careful consideration of research objectives, data characteristics, and ecological questions. Future methodological developments will likely continue to bridge these approaches, enhancing our ability to infer complex ecological processes from animal tracking data and ultimately supporting more effective conservation and management strategies.

Understanding Model Assumptions and Mathematical Underpinnings

The validation of ecological models is a cornerstone of robust scientific research, ensuring that mathematical representations accurately reflect complex natural systems. In movement ecology, where models are used to understand everything from individual animal paths to population-level migrations, validating these tools is paramount. However, a significant challenge persists: with numerous models available, it remains difficult to distinguish which ones accurately describe nature versus those that oversimplify reality [7]. For instance, in predator-prey dynamics alone, over 40 different models describe how predators consume prey based on prey availability [7]. This diversity highlights the critical need for rigorous validation methods that can test model assumptions and mathematical foundations against empirical data.

The field has traditionally relied on pattern-matching approaches, where model predictions are compared to observed data cycles or trends [7]. Yet, these methods often struggle to distinguish genuine model inadequacies from confounding effects of unobserved biotic or abiotic factors [7]. This persistent validation challenge has resulted in an accumulation of models without a corresponding accumulation of confidence in their predictive power. Recent methodological innovations are now providing more rigorous frameworks for testing the core assumptions and mathematical underpinnings of movement ecology models, offering new pathways to bridge the gap between theoretical constructs and ecological reality.

Comparative Analysis of Validation Approaches

Traditional vs. Contemporary Validation Methods

Movement ecology employs diverse approaches to model validation, each with distinct mathematical foundations and applicability. The table below summarizes key methodologies used in the field.

Table 1: Comparison of Model Validation Approaches in Movement Ecology

| Validation Method | Mathematical Foundations | Key Applications in Movement Ecology | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pattern Matching | Statistical correlation; time-series analysis | Predator-prey population cycles (e.g., lynx-hare dynamics) [7] | Cannot distinguish model inadequacies from unobserved factors [7] |

| Euler-Maruyama Approximation | Stochastic differential equations; discrete-time approximation | Parameter estimation for potential-based movement models [8] | Unstable with non-high-frequency GPS sampling [8] |

| Ozaki Linearization Method | Local linearization of drift terms; continuous-time inference | Parameter estimation for movement models [8] | More computationally intensive than Euler method [8] |

| Covariance Criteria | Queueing theory; covariance relationships between observables | Testing predator-prey functional responses; detecting higher-order interactions [7] | Establishes necessary but not always sufficient conditions for validity [7] |

| Exact Algorithm/Monte Carlo EM | Markov Chain Monte Carlo; exact simulation of diffusion paths | Inference for potential-based movement models with ecological attractors [8] | Computationally intensive for complex models [8] |

Performance Evaluation of Statistical Inference Methods

A practical study assessed inference procedures for potential-based movement models, which use gradients of attractive zones (e.g., foraging areas) in their drift terms [8]. The research compared performance across sampling frequencies, measuring stability and convergence of parameter estimates.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Inference Methods for Movement Models [8]

| Inference Procedure | Performance at Low Sampling Frequency | Performance at High Sampling Frequency | Computational Efficiency | Stability of Estimates |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Euler-Maruyama Approximation | Poor | Good | High | Low |

| Ozaki Linearization Method | Good | Good | Medium | High |

| Adaptive High-Order Gaussian Approximation | Good | Good | Medium | High |

| Monte Carlo Expectation Maximization (Exact Algorithm) | Good | Good | Low | High |

The experimental assessment demonstrated that the Euler method, commonly used in ecology, performs worse than alternative procedures for non-high-frequency GPS sampling schemes typically encountered in ecological fieldwork [8]. The Ozaki method and other advanced discretization approaches showed greater robustness across sampling regimes, performing similarly to exact methods for the tested models [8].

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

Covariance Criteria Validation Framework

The covariance criteria approach establishes a rigorous test for model validity based on necessary covariance relationships between observable quantities, regardless of unobserved factors [7]. The methodology follows these key steps:

1. Problem Formulation:

- Define the population model with Gain (G) and Loss (L) components

- Express the population change as: dN/dt = G(N) - L(N)

- Identify observable quantities from empirical data

2. Data Requirements:

- Collect time-series data on population abundances

- Ensure temporal resolution matches ecological processes

- Document environmental covariates where possible

3. Covariance Calculation:

- Compute empirical covariances between observables

- Apply statistical tests to determine significance

- Compare observed relationships with model predictions

4. Validation Decision:

- If covariance patterns match theoretical expectations, model receives support

- If mismatches occur, the model is invalidated regardless of unobserved factors

- Iterate with alternative model formulations if invalidated

This protocol was successfully applied to resolve competing models of predator-prey functional responses, disentangle ecological and evolutionary dynamics in systems with rapid evolution, and detect the influence of higher-order species interactions [7].

Case Study: Predator-Prey Model Validation

Researchers applied the covariance criteria to a classic ecological dilemma: determining the appropriate mathematical structure for predator-prey interactions [7]. The experimental protocol included:

Data Collection:

- Used a dataset of aquatic invertebrates (predator) and algae (prey) populations

- Measured population abundances at regular time intervals

- Monitored environmental conditions

Model Comparison:

- Tested traditional Lotka-Volterra model with self-regulation

- Compared against ratio-dependent functional response models

- Calculated covariance relationships for each model structure

Results:

- The traditional Lotka-Volterra model accurately described prey dynamics

- A simplified version adequately captured predator dynamics

- Ratio-dependent models were invalidated by the covariance criteria

- The analysis supported the traditional mass-action approach over ratio-dependent methods for this system [7]

Research Reagent Solutions for Movement Ecology

The experimental approaches discussed require specific methodological tools and analytical frameworks. The table below details essential "research reagents" for conducting rigorous movement ecology model validation.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Movement Ecology Validation

| Research Reagent | Function/Purpose | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| High-Resolution GPS Tracking | Captures fine-scale movement trajectories; provides primary data for parameter estimation [9] | Studying foraging behavior, migration routes, home range use [9] |

| Potential-Based Movement Models | Mathematical framework where drift is gradient of potential function; represents attractive zones [8] | Modeling movement toward resources (food, mates) or away from risks [8] |

| Stochastic Differential Equations | Incorporates random components into movement models; captures inherent unpredictability [8] | Modeling animal movement paths with both deterministic and stochastic elements [8] |

| Covariance Criteria Framework | Provides rigorous mathematical test for model validity based on necessary conditions [7] | Testing predator-prey models; detecting higher-order species interactions [7] |

| Advanced Inference Algorithms | Estimates parameters from observed movement data; superior to basic Euler method [8] | Parameter estimation for potential-based models with ecological attractors [8] |

| Multi-Species Tracking Datasets | Enables analysis of species interactions and community-level dynamics [9] | Quantifying encounter rates; studying predator-prey spatial dynamics [9] |

Visualization of Validation Workflows

Covariance Criteria Validation Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for applying the covariance criteria to ecological model validation:

Movement Model Inference Protocol

The diagram below outlines the experimental workflow for evaluating inference procedures in movement ecology:

The rigorous validation of movement ecology models requires careful consideration of both mathematical assumptions and inference procedures. Contemporary approaches like the covariance criteria offer powerful tools for testing model validity against empirical data, while advanced statistical methods provide more robust parameter estimation than traditional approximations. As movement ecology continues to integrate with conservation applications—from predicting species responses to climate change to mapping anthropogenic threats on migratory pathways [9]—the importance of reliable, validated models becomes increasingly critical. By adopting these rigorous validation frameworks, researchers can build greater confidence in models used to forecast ecological dynamics and inform conservation decisions in our rapidly changing world.

In movement ecology, understanding animal space use requires integrating multiple spatial scales, from the broad geographic boundaries of a home range to the fine-scale habitat choices made with each step. The central thesis of this field posits that animal movement is the fundamental process linking these scales, acting as the "glue" that connects patterns of home range establishment with mechanisms of habitat selection [10]. This conceptual framework has emerged through technological and analytical advances that allow researchers to track individual movements with unprecedented resolution while quantitatively assessing environmental drivers.

The distinction between second-order selection (home range placement within the landscape) and third-order selection (resource use within the home range) provides a critical foundation for understanding scale-dependent habitat relationships [11]. Meanwhile, contemporary approaches recognize that these patterns emerge from individual movement decisions influenced by both internal state (e.g., sex, reproductive status) and external environmental factors (e.g., resource distribution, predation risk) [11] [10]. This guide compares the primary methodological approaches for studying these interconnected phenomena, examining how each addresses the scale continuum from home ranges to movement-specific habitat selection.

Comparative Analysis of Methodological Approaches

Table 1: Methodological comparison for studying movement ecology across scales

| Methodological Approach | Spatial Scale | Key Measured Variables | Primary Applications | Technical Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Integrated Step Selection Analysis (iSSA) | Fine-scale (stepping decisions) | Habitat selection coefficients, movement parameters (turn angles, step lengths) | Linking movement mechanisms to habitat selection; quantifying how environmental factors influence each step [11] | GPS telemetry, environmental GIS layers, statistical modeling (R packages like amt) |

| Home Range Estimation | Broad-scale (seasonal range) | Home range size (e.g., MCP, KDE), utilization distribution | Establishing space use boundaries; quantifying effects of sex, season, and resources on space use [11] | GPS telemetry, kernel density estimators (e.g., adehabitatHR) |

| Residence Time & Time-to-Return Metrics | Multi-scale (from patches to landscapes) | Duration in specific areas, time between revisits | Identifying critical habitats; quantifying site fidelity and foraging efficiency [10] | High-resolution GPS tracking, spatial clustering algorithms |

| Experimental Pond Systems | Fine- to medium-scale (controlled environments) | Movement paths, space use in replicated ecosystems | Establishing causality through manipulation; testing effects of specific variables (e.g., predators, resources) [12] [13] | Acoustic telemetry arrays, replicated pond infrastructures, experimental manipulations |

Table 2: Data requirements and analytical outputs across movement ecology approaches

| Approach | Tracking Data Requirements | Environmental Data Integration | Key Analytical Outputs | Scale Bridging Capabilities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| iSSA | High-frequency relocations (minutes-hours) | Continuous habitat variables at fine spatial resolution | Resource selection coefficients; movement parameters conditional on environment; inference on behavioral mechanisms [11] | Directly connects fine-scale movement decisions to emergent home range patterns |

| Home Range Analysis | Moderate-frequency relocations (hours-days) over extended periods | Landscape-scale habitat composition and configuration | Home range size estimates; core use areas; seasonal variation in space use [11] | Defines broad-scale spatial context for finer-scale analyses |

| Time-Based Metrics | High-resolution paths over appropriate temporal windows | Patch-level habitat characteristics | Maps of area-restricted search; identification of functionally significant sites; foraging efficiency measures [10] | Links behavioral states to spatial memory and resource renewal processes |

| Experimental Systems | Complete system coverage with precise positioning | Full control and manipulation of environmental variables | Causal relationships; individual behavioral variation; response to specific perturbations [12] [13] | Isolates processes across scales in controlled settings |

Experimental Protocols in Movement Ecology

Integrated Step Selection Analysis (iSSA) Protocol

The iSSA framework represents a significant methodological advancement for simultaneously investigating animal movement and habitat selection. The following protocol outlines its key implementation steps:

Step 1: Data Collection - Fit free-ranging animals with GPS telemetry collars programmed to record locations at regular intervals (e.g., every 1-4 hours) across multiple seasons to capture temporal variation in movement patterns [11]. In the Iberian ibex study, researchers collected 700-3,230 fixes per individual over 206-576 days to ensure robust seasonal analysis [11].

Step 2: Environmental Layer Preparation - Compile Geographic Information System (GIS) layers representing relevant environmental variables (e.g., vegetation type, elevation, slope, distance to water) at spatial resolutions matching the scale of animal movement. These layers enable quantitative assessment of habitat characteristics influencing movement decisions.

Step 3: Used and Available Steps Generation - For each observed movement step (the linear segment between two consecutive GPS fixes), generate a set of alternative "available" steps that the animal could have taken but did not. These available steps are typically matched to observed steps by starting point and sampling randomly from the empirical step-length and turning-angle distributions [11].

Step 4: Habitat Covariate Extraction - Extract environmental variables at the starting point and endpoint of each observed and available step. This creates a dataset where each step is characterized by its movement characteristics and the habitat conditions it traverses.

Step 5: Conditional Regression Modeling - Implement a conditional logistic regression model where observed steps are compared against available steps. This models the probability of selecting a step given its movement characteristics and habitat conditions, effectively integrating movement constraints with habitat selection [11].

Step 6: Interpretation and Application - Interpret coefficients for habitat variables as selection strength while accounting for intrinsic movement patterns. These models can reveal how habitat selection constrains movement, which in turn affects emergent space-use patterns like home range size and structure [11].

Experimental Pond System Protocol

Replicated pond infrastructures offer unprecedented opportunities for causal inference in movement ecology through experimental manipulation:

Step 1: System Establishment - Create or utilize existing replicated pond systems with similar physical characteristics (e.g., size ~90×30m, depth ~1.5m, substrate composition) to ensure experimental control [13]. The iPonds infrastructure in Sweden exemplifies such a system, specifically designed for movement ecology research.

Step 2: Acoustic Telemetry Array Installation - Equip each pond with a dense array of acoustic telemetry receivers (e.g., 8 receivers per pond) positioned to enable complete coverage and accurate multilateration for precise positioning of tagged animals [13].

Step 3: Animal Tagging - Surgically implant acoustic transmitters into the body cavity of study animals. In fish studies, ensure tagging procedures minimize physiological impacts and allow adequate recovery before experimentation [13].

Step 4: Experimental Manipulation - Manipulate variables of interest while maintaining appropriate controls. Potential manipulations include:

- Habitat structure modifications (e.g., vegetation removal or addition)

- Predator presence/absence using caged predators to manipulate perceived risk

- Resource distribution adjustments

- Community composition alterations [13]

Step 5: Data Collection - Monitor movement patterns continuously throughout the experimental period, leveraging the high-resolution positioning capabilities of the acoustic array. The temporal resolution can be adjusted based on experimental needs through transmitter programming [13].

Step 6: Path Reconstruction and Analysis - Reconstruct complete movement paths using multilateration techniques, then apply movement metric analyses (e.g., step length, turning angle, residence time) to quantify behavioral responses to experimental manipulations [13].

Conceptual Framework Diagrams

Movement Ecology Conceptual Framework

iSSA Methodological Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Equipment

Table 3: Essential research tools for movement ecology studies across scales

| Tool Category | Specific Equipment/Technology | Primary Function | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tracking Technologies | GPS telemetry collars | Record animal locations at programmed intervals | Home range estimation, movement path reconstruction [11] |

| Acoustic telemetry transmitters and receivers | Underwater animal tracking using ultrasonic signals | Aquatic movement studies in lakes, ponds, and oceans [12] [13] | |

| Habitat Assessment Tools | Geographic Information Systems (GIS) | Spatial analysis of environmental variables | Mapping habitat characteristics, resource distribution [11] |

| Remote sensing platforms (satellites, drones) | Broad-scale habitat mapping | Landscape-scale habitat classification and monitoring [9] | |

| Experimental Infrastructure | Replicated pond systems | Controlled experimental arenas for aquatic studies | Hypothesis testing with full environmental control [12] [13] |

| Mobile terrestrial enclosures | Semi-controlled field experiments | Manipulating terrestrial habitat features [14] | |

| Analytical Frameworks | Integrated Step Selection Analysis (iSSA) | Simultaneously model movement and habitat selection | Quantifying habitat selection while accounting for movement constraints [11] |

| Residence Time/Time-to-Return metrics | Quantify area-restricted search and site fidelity | Identifying critical habitats and foraging areas [10] |

The most powerful insights in movement ecology emerge from integrating multiple methodological approaches, each addressing different aspects of the scale continuum. Home range analysis establishes the broad spatial context of animal space use, while integrated step selection analysis reveals the fine-scale mechanisms generating these patterns through sequential habitat choices. Meanwhile, experimental approaches using replicated systems like pond infrastructures provide causal validation of hypothesized relationships.

Future methodological development should focus on better bridging these scales, particularly through approaches that explicitly link short-term movement decisions to long-term space use outcomes. The field is moving toward frameworks that can forecast animal movement under environmental change, requiring robust validation through integrated observational and experimental approaches across spatiotemporal scales [9]. This comparative guide provides a foundation for selecting appropriate methodologies based on specific research questions about animal movement and habitat relationships across organizational levels.

The Critical Importance of Model Validation in Regulatory and Research Contexts

Model validation is a critical pillar in both regulatory and research contexts, ensuring that statistical and mathematical models are reliable, accurate, and generalizable. In movement ecology—a field increasingly reliant on complex models to understand animal movement across scales—robust validation is what transforms a theoretical pathway into a trustworthy prediction, with profound implications for conservation and policy [9] [15]. As models underpin more high-stakes decisions, from drug development to species protection, the process of validating them has evolved from a technical step to a fundamental scientific practice. This guide objectively compares core validation methodologies, providing researchers with the experimental protocols and tools necessary to implement them effectively.

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

Adhering to a structured, methodical process is key to sound model validation. The following workflow outlines the critical stages, from initial data preparation to final model selection.

Detailed Methodologies

The general workflow above is operationalized through specific, rigorous techniques:

Data Partitioning and Cross-Validation: The foundational step is to split the available data into distinct subsets. A common approach is the holdout method, where data is divided into a training set (e.g., 70%) for model fitting, a validation set (e.g., 15%) for comparison and tuning, and a test set (e.g., 15%) for the final, unbiased evaluation [16]. For more robust validation, K-Fold Cross-Validation is preferred. This technique partitions the data into K subsets (or "folds"). The model is trained K times, each time using a different fold as the validation set and the remaining K-1 folds as the training set. The final performance metric is the average across all K trials [15] [17]. This reduces variability and provides a more reliable estimate of model performance on unseen data.

Performance Metric Calculation: Once the data is partitioned, relevant metrics are calculated on the validation set to quantify model performance. The choice of metrics is problem-dependent. For regression models (e.g., predicting migration distance), common metrics include Mean Squared Error (MSE) and R-squared [16]. The MSE is calculated as:

MSE = (1/n) * Σ(actual - forecast)²[15] where n is the number of observations. For classification models (e.g., identifying behavioral states from movement data), researchers use metrics like Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and the F1-score, which combines precision and recall into a single metric [16] [17].Model Comparison and Selection: With metrics calculated for each candidate model, the final step is comparison and selection. This involves more than just picking the model with the best metric. Researchers must contrast models by considering complexity, interpretability, and robustness [16]. A slightly less accurate but vastly simpler model is often preferable for explaining ecological mechanisms. Information criteria like the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) are commonly used for formal model comparison, as they penalize model complexity to guard against overfitting [15].

Comparison of Validation Metrics and Techniques

Different validation metrics and techniques offer unique insights, and their appropriate application depends on the model's purpose—whether for explanation or prediction. The tables below provide a structured comparison.

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics for Model Validation

| Metric | Primary Use Case | Interpretation | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Squared Error (MSE) [15] | Regression Models (e.g., forecasting movement paths) | Measures average squared difference between predicted and actual values. Closer to 0 is better. | Provides a strong penalty for large errors. mathematically convenient. | Sensitive to outliers; value is not in original units. |

| Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) [15] | Model Comparison & Selection | Estimates relative information loss. Lower values indicate a better model. | Balances model fit and complexity; useful for model selection. | Does not provide a test for a single model; relative measure only. |

| F1-Score [17] | Classification Models (e.g., identifying foraging vs. migration) | Harmonic mean of precision and recall. Ranges from 0 (worst) to 1 (best). | Balances the trade-off between precision and recall. | Can be misleading with imbalanced class distributions. |

| ROC-AUC [17] | Binary Classification Models | Measures the model's ability to distinguish between classes. Closer to 1 is better. | Provides a comprehensive view across all classification thresholds. | Less informative for datasets with high class imbalance. |

Table 2: Comparison of Core Validation Techniques

| Technique | Methodology | Best For | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Holdout Validation [16] [17] | Simple random split into training and holdout sets. | Large datasets, initial model prototyping. | Simple and computationally efficient. | Performance estimate can be highly variable based on the split. |

| K-Fold Cross-Validation [17] | Data divided into K folds; each fold serves as validation once. | Medium-sized datasets, robust performance estimation. | Reduces variability; uses all data for both training and validation. | Computationally intensive; requires multiple model fits. |

| Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation (LOOCV) [17] | A special case of K-Fold where K equals the number of data points. | Very small datasets. | Minimizes bias; uses nearly all data for training. | Extremely computationally expensive; high variance in estimates. |

| Bootstrapping [15] | Resamples the dataset with replacement to create multiple simulated datasets. | Assessing model stability, particularly with limited data. | Effective for estimating the sampling distribution of a statistic. | Can lead to overly optimistic results if not carefully implemented. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Building and validating a robust movement ecology model requires a suite of methodological "reagents." The following toolkit details essential components, from conceptual frameworks to analytical techniques.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions in Movement Ecology Modeling

| Research Reagent | Function & Purpose | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Hierarchical Movement Framework [9] | A conceptual tool that partitions an animal's trajectory into nested behavioral modes (e.g., foraging, commuting) and broader phases (e.g., seasonal migration). | Enables multi-scale analysis, linking short-term decisions to lifetime dispersal events to forecast range shifts under climate change [9]. |

| Reaction-Diffusion Theory [9] | A mathematical framework derived from statistical physics to model encounters between moving animals as first-passage events. | Provides rigorous quantification of encounter rates for processes like predation and disease transmission, moving beyond simplistic "ideal gas" models [9]. |

| Energetics-Informed Network Model [9] | A pathfinding model (e.g., using Dijkstra's algorithm) modified with energy constraints and environmental data like wind patterns. | Used to reconstruct and predict plausible long-distance migration routes for insects like the globe-skimmer dragonfly [9]. |

| Agent-Based Modeling (ABM) [9] | A simulation technique where individual "agents" (e.g., birds in a flock) follow a set of behavioral rules, with group-level patterns emerging from their interactions. | Used to analyze how individual rules of alignment and cohesion lead to collective escape maneuvers from predators [9]. |

| Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) [18] | A statistical method that infers unobserved (hidden) behavioral states from sequential, observed movement data (e.g., step length, turning angle). | Commonly applied to classify animal tracking data into discrete behavioral states such as "resting," "foraging," and "transit" [18]. |

| Satellite Telemetry & Biologging Data [9] | The primary empirical data source, providing high-resolution recordings of animal movement paths, often coupled with environmental sensors. | Compiled to create comprehensive maps of migratory marine megafauna and assess their overlap with anthropogenic threats like shipping traffic [9]. |

The relationships and applications of these tools within a research workflow can be visualized as follows:

A Guide to Common Pitfalls and Best Practices

Even with the right tools, validation can fail if best practices are not followed. Here is a critical summary of common challenges and their solutions.

Table 4: Common Validation Pitfalls and Mitigation Strategies

| Common Challenge | Description | Consequence | Best Practice & Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overfitting [16] [17] | Model is too complex and fits the training data noise, not the signal. | Poor generalization to new, unseen data (high training accuracy, low validation accuracy). | Use regularization techniques, feature selection, and cross-validation to tune complexity [17]. Prefer simpler, more interpretable models where possible [16]. |

| Data Leakage [17] | Information from the test or validation set inadvertently influences the training process. | Over-optimistic performance estimates that do not reflect real-world performance. | Strictly partition data before any analysis; perform all feature engineering using only the training set. |

| Ignoring Data Quality [17] | Building models on data with missing values, outliers, or biases. | Skewed and unreliable predictions, reinforcing existing biases. | Implement rigorous data cleaning, preprocessing (e.g., handling missing values), and exploratory data analysis [15] [17]. |

| Misinterpreting Metrics [16] | Relying on a single metric (e.g., accuracy for imbalanced classification). | A false sense of model competency, missing critical weaknesses. | Use multiple evaluation metrics (e.g., precision, recall, F1) to gain a comprehensive view of performance [16] [17]. |

| Neglecting Domain Expertise | Validating a model based solely on statistical metrics without ecological context. | Model may be statistically sound but ecologically irrelevant or misleading. | Collaborate with domain experts to interpret results and ensure model outputs align with biological understanding [17]. |

In high-stakes fields like movement ecology and drug development, model validation is the non-negotiable practice that separates conjecture from reliable science. It is a multifaceted process, demanding careful data management, the strategic application of techniques like cross-validation, and the clear-eyed interpretation of multiple performance metrics. By adopting the rigorous protocols and best practices outlined in this guide—using structured workflows, comparing models with appropriate metrics, leveraging specialized analytical tools, and vigilantly avoiding common pitfalls—researchers can build models that are not only statistically sound but also truly fit for purpose. This commitment to robust validation is what ensures that models can effectively inform conservation policy, regulatory decisions, and our fundamental understanding of the natural world.

In the field of movement ecology, accurately interpreting animal behavior from tracking data is fundamental. Traditional model validation often involves a binary check against a limited set of known truths. However, this approach can be insufficient for complex behavioral models, leading to a proposed shift in terminology and practice towards comprehensive evaludation—a broader process that encompasses validation, verification, and uncertainty quantification [19]. This guide compares traditional validation against the semi-supervised evaludation framework, demonstrating how the latter significantly enhances behavioral inference, particularly for species exhibiting subtle behavioral differentiations.

Comparative Performance Analysis: Validation vs. Semi-Supervised Evaludation

A 2023 study on red-billed tropicbirds provides quantitative evidence for the superiority of the evaludation approach. The research used Hidden Markov Models to classify GPS tracks into behavioral states, comparing a traditional unsupervised HMM with a semi-supervised HMM that incorporated a small subset of data labeled with behaviors from auxiliary sensors [19].

Table 1: Overall Model Performance Comparison

| Metric | Unsupervised HMM | Semi-Supervised HMM | Performance Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Accuracy | 0.77 ± 0.01 | 0.85 ± 0.01 | +0.08 [19] |

| Data Informed | None | 9% of full dataset | - |

While overall accuracy improved notably, the evaludation framework's impact varied significantly by behavioral state.

Table 2: State-Specific Model Performance (Semi-Supervised HMM)

| Behavioural State | Sensitivity (True Positive Rate) | Precision (Positive Predictive Value) |

|---|---|---|

| Foraging | 0.37 ± 0.06 | 0.06 ± 0.01 [19] |

| Travelling | Data not available in search results | Data not available in search results |

| Resting | Data not available in search results | Data not available in search results |

The low precision for foraging indicates that even the improved model frequently misclassifies other behaviors as foraging. This highlights a key finding: the benefit of semi-supervision is state-dependent. It is most effective for behaviors with distinct movement patterns but struggles with "foraging on the go" in homogenous environments [19].

Experimental Protocols: Implementing a Semi-Supervised Evaludation

Fieldwork and Data Collection

The foundational study was conducted on red-billed tropicbirds across several colonies in Cabo Verde between 2017 and 2021 [19]. The experimental protocol involved:

- Primary Tracking: Birds were equipped with GPS loggers programmed to record positions every 5 minutes.

- Auxiliary Sensor Deployment: A subset of birds was co-tagged with:

- Tri-axial accelerometers (25 Hz) to capture fine-scale movements and posture.

- Time Depth Recorders (TDR) (1s intervals) to detect dive events.

- Wet-dry sensors (every 6s) to determine immersion in saltwater [19].

- Data Integration: GPS data was transformed into a bivariate series of step lengths and turning angles, the standard inputs for HMMs.

Behavioural Labelling from Auxiliary Data

The data from auxiliary sensors were used to definitively label GPS fixes with behaviors, creating a "ground-truth" subset:

- Resting: Inferred from wet-dry data indicating prolonged dry periods, likely on land or at the sea surface.

- Foraging: Identified via a combination of dive events from TDR data and characteristic burst-and-glide movements from accelerometers.

- Travelling: Characterized by directed, sustained flight without associated diving or foraging-associated movements [19].

Model Fitting and Evaludation

The methodology compared two modelling approaches:

- Unsupervised HMM: An HMM was fitted using only the GPS-derived movement metrics (step length and turning angle) for the entire population.

- Semi-Supervised HMM: The same HMM structure was fitted, but the model was informed by the known behavioural states from the auxiliary sensor subset, which represented 9% of the full dataset. This "semi-supervision" guides the model to more accurately learn the movement signatures of each behavior [19].

The workflow is illustrated in the diagram below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Movement ecology research relies on a suite of sophisticated biologging technologies and analytical tools.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Movement Ecology Evaludation

| Tool / Reagent | Primary Function | Specific Application in Evaludation |

|---|---|---|

| GPS Loggers | Records high-frequency location data. | Provides core movement metrics (step length, turning angle) for state-space models [19]. |

| Tri-axial Accelerometer | Measures dynamic body acceleration across three axes. | Validates fine-scale behaviors (e.g., foraging attempts, flight mode) for ground-truth labeling [19]. |

| Time Depth Recorder (TDR) | Logs pressure/depth over time. | Objectively identifies diving and underwater foraging activity in marine species [19]. |

| Wet-Dry Sensor | Detects immersion in water based on conductivity. | Helps distinguish resting on water from flight and land-based activities [19]. |

| Hidden Markov Model (HMM) | A statistical framework for classifying sequences of data into hidden states. | The core analytical model for inferring latent behavioral states from movement data [20] [19]. |

| Semi-Supervised Learning | A machine learning paradigm that uses both labeled and unlabeled data. | The core of the evaludation framework, using a small, informed dataset to drastically improve behavioral classification for a larger dataset [19]. |

The transition from simple validation to a comprehensive evaludation framework marks a significant advancement in movement ecology. The empirical evidence clearly demonstrates that integrating a small subset of multi-sensor data into HMMs significantly improves behavioral classification accuracy. This approach is particularly valuable for resolving the persistent challenge of accurately identifying foraging behavior in opportunistically foraging species within homogenous environments [19]. Future research should focus on developing more accessible tools for implementing semi-supervised models and exploring their application across a wider range of species and ecosystems.

From Theory to Practice: Implementing and Applying Movement Ecology Models

A Step-by-Step Guide to Developing a Resource Selection Function (RSF)

Within movement ecology, validating models of animal-space use is fundamental for robust ecological inference and effective conservation planning. A Resource Selection Function (RSF) is a cornerstone model that quantifies the relative probability of an animal using a resource unit based on its environmental characteristics [1]. This guide provides a step-by-step protocol for developing an RSF, objectively compares its performance against alternative step-selection functions (SSFs) and hidden Markov models (HMMs), and frames the discussion within the critical context of model validation. Supported by experimental data and detailed workflows, this guide serves as a practical toolkit for researchers.

A Resource Selection Function (RSF) is a statistical model widely used to understand species-habitat associations by relating the habitat characteristics at locations used by an animal to those available to it [1]. The RSF, denoted as ( w(\mathbf{x}) ), is typically an exponential function of linear predictors: ( w(\mathbf{x}) = \exp( \beta{1} x{1} + \beta{2} x{2} + \cdot \cdot \cdot + \beta{k} x{k} ) ), where ( \mathbf{x} ) represents the values of k predictor habitat variables and ( {\beta }{1}),…, ( {\beta }{k} ) are the selection coefficients to be estimated [1]. Positive coefficients indicate selection for a habitat feature, while negative coefficients indicate avoidance [4].

RSFs operate on a use-available design, which contrasts environmental covariates at locations observed to be used by an animal with those from a sample of locations deemed available to it within a defined availability domain, such as a home range [1] [4]. This framework allows researchers to test hypotheses about the environmental drivers of habitat selection, which is often categorized into different orders, from the selection of a home range within the species' geographical range (second-order selection) to the selection of specific habitat features within the home range (third-order selection) [1].

A Step-by-Step Protocol for RSF Development

Step 1: Data Preparation and Definition of "Used" Locations

- Objective: Compile the dataset of animal locations, often obtained via GPS telemetry, that will be classified as "used."

- Protocol:

- Data Sourcing: Use cleaned and pre-processed animal movement data. The temporal resolution should be appropriate for the research question; RSFs can often accommodate lower-frequency data compared to other models like SSFs [1].

- Subsampling: To mitigate the effects of spatial autocorrelation, which can inflate the sample size and lead to overconfident models, consider subsampling the movement track [4]. For instance, in a caribou case study, researchers subsampled 200 out of thousands of observed locations for analysis [4].

Step 2: Defining "Availability"

- Objective: Determine the spatial domain that represents the area accessible to the animal, from which "available" locations will be randomly sampled.

- Protocol:

- Common Methods: The availability domain is often defined using a home range estimator. Simple methods include the Minimum Convex Polygon (MCP). More complex methods include Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) or Brownian Bridge Movement Models (BBMM) [4].

- Implementation: Using R, an MCP can be calculated with the

adehabitatHRpackage. Available points are then generated within this polygon using thespsamplefunction. A common practice is to generate a larger number of available points than used points (e.g., 1000 available vs. 200 used) to ensure a robust comparison [4].

Step 3: Extracting Environmental Covariates

- Objective: Obtain the values of relevant environmental variables (e.g., elevation, vegetation cover, distance to roads) at both used and available locations.

- Protocol:

- Data Sources: Covariates are typically stored as raster layers in a GIS.

- Extraction: Use the

raster::extract()function in R to sample the values of each environmental covariate at the coordinates of every used and available point [4]. This creates the final dataset for modeling, with columns for location type (Used TRUE/FALSE) and the extracted covariate values.

Step 4: Model Fitting with Logistic Regression

- Objective: Estimate the selection coefficients (( \beta )) of the RSF.

- Protocol:

- Statistical Model: The RSF is statistically equivalent to an inhomogeneous Poisson point process (IPP) and can be fitted using logistic regression on the used/available data [1]. The model is:

glm(Used ~ scale(covariate1) + scale(covariate2) + ..., data = Data.rsf, family = "binomial")[4]. - Scaling Covariates: It is good practice to scale and center covariates (e.g., using

scale()) to improve model convergence and make coefficients comparable [4]. - Model Selection: To find the most parsimonious model, compare candidate models with different combinations of covariates and interactions using Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) [21]. For example, a model with an interaction between elevation and distance to roads may have a significantly lower AIC than a model without it [4].

- Statistical Model: The RSF is statistically equivalent to an inhomogeneous Poisson point process (IPP) and can be fitted using logistic regression on the used/available data [1]. The model is:

Step 5: Model Validation

- Objective: Assess the predictive performance and robustness of the fitted RSF.

- Protocol:

- k-Fold Cross-Validation: A standard method is fivefold cross-validation. The data (both used and available points) are split into five folds. The model is trained on four folds and used to predict to the withheld fold. This process is repeated five times [21].

- Evaluation Metric: The predictive power is assessed by calculating the Spearman rank correlation coefficient (( r_s )) between the ranked RSF predictions and the observed use of the withheld data. A high correlation indicates good predictive performance [21].

Step 6: Interpretation and Mapping

- Objective: Interpret the model coefficients and create a predictive map of relative probability of use across the landscape.

- Protocol:

- Coefficient Interpretation: Plot the model coefficients (e.g., using the

sjPlotpackage) to visualize selection and avoidance. A positive coefficient for elevation means animals select for higher elevations [4]. - RSF Map Creation: Use the

predict()function with the fitted model and a raster stack of environmental covariates to predict the RSF value (( w(\mathbf{x}) )) for every pixel in the study area. The result is a map of the relative probability of use [4].

- Coefficient Interpretation: Plot the model coefficients (e.g., using the

The following workflow diagram summarizes the key steps in the RSF development process.

Quantitative Comparison of Habitat Selection Models

While RSFs are powerful, other models like Step-Selection Functions (SSFs) and Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) offer different approaches and insights. The table below compares these models based on key criteria, with data synthesized from a comparative review [1].

Table 1: Comparative analysis of Resource Selection Functions (RSFs), Step-Selection Functions (SSFs), and Hidden Markov Models (HMMs).

| Feature | Resource Selection Function (RSF) | Step-Selection Function (SSF) | Hidden Markov Model (HMM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Unit of Analysis | Individual "used" GPS locations [1] | Paired "used" and "available" steps (vectors between consecutive locations) [1] | Sequence of observations (e.g., steps, turns) linked to latent behavioral states [1] |

| Temporal Data Resolution | Lower frequency often sufficient [1] | Requires high-frequency data [1] | Requires high-frequency data [1] |

| Handling of Autocorrelation | Often requires subsampling to mitigate [4] | Explicitly controls for it by conditioning on the animal's previous location [1] | Explicitly models it as a state-dependent process [1] |

| Primary Ecological Inference | Habitat selection at the scale of the availability domain [1] | Habitat selection during movement, integrated with movement mechanics [1] | How habitat relates to discrete, latent behavioral states (e.g., foraging vs. traveling) [1] |

| Key Advantage | Simplicity; provides broad-scale habitat preference maps [1] | More realistic integration of movement and selection; avoids some biases of RSFs [1] | Reveals variable habitat associations across different behaviors [1] |

Experimental Data from a Model Comparison Case Study

A case study on a ringed seal (Pusa hispida) directly compared RSF, SSF, and HMM outputs, providing critical empirical evidence for their differential performance [1].

Table 2: Contrasting results from a ringed seal case study applying RSF, SSF, and HMM to the same movement track (adapted from [1]).

| Model | Relationship with Prey Diversity | Identified "Important" Areas |

|---|---|---|

| RSF | Stronger positive relationship (though not always significant after accounting for autocorrelation) [1] | Different areas identified compared to SSF and HMM [1] |

| SSF | Weaker positive relationship than RSF (often not significant after accounting for autocorrelation) [1] | Different areas identified compared to RSF and HMM [1] |

| HMM | Positive relationship with prey diversity specifically during a slow-moving, area-restricted search behavior (likely foraging) [1] | Different areas identified compared to RSF and SSF [1] |

This case study demonstrates that the choice of model can lead to varying ecological insights and identify different areas as important. The HMM, in particular, provided a more nuanced understanding by linking habitat use (prey diversity) to a specific behavior.

Successful implementation of habitat selection analyses requires a suite of computational tools and data resources.

Table 3: Essential tools and packages for developing resource selection and movement models in R.

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Citation/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

amt |

R Package | Provides a unified framework for animal movement telemetry analyses, including track creation, SSF simulation, and RSF development [1]. | [1] [4] |

adehabitatHR |

R Package | Calculates animal home ranges using various methods like MCP and KDE, which are crucial for defining availability in RSFs [4]. | [4] |

momentuHMM |

R Package | Fits sophisticated HMMs to animal movement data, allowing the incorporation of environmental covariates into state-dependent distributions [1]. | [1] |

ResourceSelection |

R Package | Specifically designed for fitting resource selection (probability) functions, including goodness-of-fit tests like the Hosmer-Lemeshow test [22]. | [22] |

raster |

R Package | Core package for handling and extracting data from spatial raster layers, which is essential for obtaining environmental covariates [4]. | [4] |

| GPS Telemetry Collars | Hardware | Provides the primary data source—high-resolution spatiotemporal location data—for all movement analyses. | [21] |

| Environmental GIS Rasters | Data | Spatial layers representing habitat covariates (e.g., elevation, land cover, vegetation indices) that are linked to animal locations. | [4] [21] |

Advanced Considerations and Future Directions

The Contact RSF: An Innovative Extension

Moving beyond individual habitat selection, the RSF framework has been innovatively extended to model contacts between individuals. A study on wild pigs (Sus scrofa) developed a contact-RSF model, where "used" points were contact locations between individuals, and "available" points were non-contact locations within their overlapping home ranges [21]. This model revealed that the landscape predictors (e.g., wetlands, linear features) driving contact locations were different from those driving general habitat selection (individual-RSF) [21]. This finding is critical as it challenges the common assumption that spatial overlap of individual RSFs can accurately predict contact hotspots, with direct implications for understanding disease transmission dynamics [21].

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual and data structural differences between a standard RSF and a contact-RSF.

Future Directions in Model Validation

The future of movement model validation lies in multi-model frameworks and robust cross-validation techniques. As the ringed seal case study showed, relying on a single model can yield a narrow or potentially misleading perspective [1]. Future research should:

- Embrace Multi-Model Inference: Apply and compare RSF, SSF, and HMM frameworks to the same dataset to gain a comprehensive, behaviorally explicit understanding of habitat selection [1].

- Prioritize Independent Validation: Always validate models with out-of-sample data using structured protocols like k-fold cross-validation, rather than relying solely on in-sample fit statistics like AIC [21].

- Incorporate Biological Realism: Move beyond simple MCPs for defining availability and use more biologically realistic availability domains derived from movement models, such as those accounting for diffusion-based space use or memory [4].

Leveraging Step Selection Functions (SSFs) for Fine-Scale Movement Analysis

Step-Selection Functions (SSFs) represent a powerful framework in movement ecology for integrating animal movement trajectories with environmental covariates to quantify habitat selection and movement constraints. This comparative guide examines SSFs alongside alternative statistical models, including Resource Selection Functions (RSFs) and Hidden Markov Models (HMMs), highlighting their distinct mathematical foundations, application domains, and inferential capabilities. We present experimental data and protocols from key studies, synthesizing quantitative comparisons of model performance and providing a structured toolkit for researchers seeking to apply these methods to fine-scale movement analysis. Within the broader thesis of movement ecology model validation, this guide emphasizes the critical importance of matching model selection to specific research questions and data structures.

Understanding species-habitat relationships is fundamental to ecological research and conservation [23]. The analysis of animal movement data has been revolutionized by the advent of high-resolution biologging technology, which provides massive amounts of sequential spatial data on animal trajectories [24] [9]. Statistical models that relate these movement data to environmental indicators enable researchers to infer resource selection, identify critical habitats, and understand behavioral mechanisms [23]. Step-Selection Functions (SSFs) have emerged as particularly valuable tools for studying resource selection by animals moving through a landscape because they explicitly incorporate movement constraints into habitat selection analyses [24] [25].

SSFs belong to a broader family of habitat selection models that also includes Resource Selection Functions (RSFs) and behavior-oriented approaches like Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) [23]. Each model class operates on different principles, requires different data resolutions, and yields distinct ecological insights [23]. For instance, while RSFs provide broad-scale information on species-habitat relationships, SSFs offer a more nuanced understanding of how movement capacities interact with environmental features to shape space use patterns [24] [23]. The validation of these movement ecology models requires careful consideration of their underlying assumptions, data requirements, and inferential limitations.

Model Comparison: SSFs vs. Alternative Approaches

Conceptual Foundations and Mathematical Formulations

Step-Selection Functions (SSFs) compare environmental attributes of observed steps (the linear segment between two consecutive positions) with alternative random steps taken from the same starting point [24]. The SSF is typically defined as an exponential function of the form w(x) = exp(βx), where x represents a vector of habitat covariates and β are selection coefficients [24]. This approach conditions each step on the previous location, thereby explicitly incorporating the serial correlation inherent in movement data [24] [25]. SSFs can be framed as an approximation to space-time point process models, with the general form:

[ [\textbf{s}(ti)|\textbf{s}(t{i-1}),\varvec{\beta}] \equiv \frac{g(\textbf{w}(\textbf{s}(ti)),\varvec{\beta})fi(\textbf{s}(ti)|\textbf{s}(t{i-1}))}{\int{\mathcal{S}}g(\textbf{w}(\textbf{s}),\varvec{\beta})fi(\textbf{s}|\textbf{s}(t_{i-1}))d\textbf{s}} ]

where (f_i) represents the movement kernel and (g) weights this kernel based on habitat resources [25].

Resource Selection Functions (RSFs) are traditionally defined as any function proportional to the probability of selection of a spatial resource unit [24] [23]. RSFs compare environmental conditions at used locations versus available locations typically drawn from the animal's home range [23]. The standard exponential RSF takes the form w(x) = exp(β₁x₁ + β₂x₂ + ··· + βₖxₖ), with coefficients estimated via logistic regression comparing used and available locations [23]. RSFs can also be formulated as inhomogeneous Poisson point processes (IPPs) that model the density of animal locations across geographical space [23].

Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) take a fundamentally different approach by assuming an animal's movement arises from multiple behavioral states (e.g., resting, foraging, relocating), each characterized by distinct movement characteristics and habitat selection patterns [23] [26]. HMMs incorporate latent behavioral states that are inferred probabilistically from the observed movement data, allowing researchers to link specific behaviors to environmental covariates [23] [26].

Comparative Analysis of Model Characteristics

Table 1: Comparison of Key Characteristics Between Movement Analysis Models

| Characteristic | Step-Selection Functions (SSFs) | Resource Selection Functions (RSFs) | Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Question | How do movement and habitat selection interact? | Where is habitat selected? | How does habitat relate to behavioral states? |

| Scale of Inference | Fine-scale (3rd-4th order selection) | Broad-scale (2nd-3rd order selection) | Behavior-specific selection |

| Temporal Resolution | High (regular or irregular intervals) | Lower (independent locations) | High (regular intervals) |

| Movement Constraints | Explicitly incorporated | Not incorporated | Incorporated via state-dependent distributions |

| Behavioral Inference | Limited without extensions | Not applicable | Explicit state estimation |

| Availability Definition | Movement-based from previous location | Home range or study area | Varies by implementation |

| Typical Data Requirements | GPS tracks with short intervals | GPS or VHF locations | High-frequency GPS data |

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Table 2: Experimental Comparison of Model Performance from Empirical Studies

| Study System | Model | Key Covariates | Predictive Performance | Behavioral Insights |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Muskoxen (High Arctic) [26] | Behavior-specific SSF | Terrain, vegetation, snow | Improved for foraging/relocating | State-dependent selection tradeoffs |

| Behavior-unspecific SSF | Terrain, vegetation, snow | Lower overall performance | Masked state-specific selections | |

| Ringed Seal [23] | SSF | Prey diversity | Non-significant relationship | Limited behavioral context |

| RSF | Prey diversity | Stronger apparent relationship (potentially spurious) | No behavioral discrimination | |

| HMM | Prey diversity | Variable by behavior (positive with slow movement) | Clear state-dependent selection | |

| Mountain Lion [25] | Rayleigh SSF | Landscape features | Improved with irregular intervals | Continuous-time movement |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Core SSF Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the standard workflow for implementing Step-Selection Function analysis:

SSF Workflow Diagram

Detailed Methodological Protocols

Objective: To evaluate how accounting for behavior in SSFs influences habitat selection inference.

Step 1: Data Collection

- Collect high-resolution GPS data (e.g., hourly positions) from study individuals

- Record environmental covariates: terrain features, vegetation metrics, snow conditions

Step 2: Behavioral State Inference

- Apply Hidden Markov Models to classify movements into behavioral modes (resting, foraging, relocating)

- Use characteristic movement patterns: step lengths and turning angles for each state

- Validate state classification using field observations or posterior probability checks

Step 3: Behavior-Specific SSF Implementation

- Define availability domains separately for each behavioral state

- Generate random steps from state-specific distributions of step lengths and turning angles

- Fit separate SSF models for each behavioral state using conditional logistic regression

- Compare with behavior-unspecific SSF that pools all data

Step 4: Model Evaluation

- Assess predictive performance using cross-validation or out-of-sample prediction

- Compare variable selection and coefficient estimates between models

- Evaluate ecological interpretability of state-specific selection patterns

Key Findings: Behavior-specific availability domains improved predictive performance for foraging and relocating models but decreased performance for resting models. Fitting separate behavior-specific models primarily influenced selection strength estimates [26].

Objective: To implement continuous-time SSF that accommodates irregular sampling intervals.

Step 1: Ecological Diffusion Theory Foundation

- Derive availability distributions from ecological diffusion principles

- Use Rayleigh distribution for step lengths: ( f(l) = \frac{l}{\sigma^2} \exp\left(-\frac{l^2}{2\sigma^2}\right) )

- Use uniform distribution for turning angles: ( f(\theta) = \frac{1}{2\pi} )

Step 2: Motility Estimation

- Calculate homogenized motility coefficient using temporal moving average: ( \bar{\delta}(ti) \approx \sum{tj \sim ti} \frac{(\textbf{s}(tj)-\textbf{s}(t{j-1}))'(\textbf{s}(tj)-\textbf{s}(t{j-1}))}{4ni\Delta tj} )

- Adjust for spatial grain and temporal interval irregularity

Step 3: SSF Estimation with Rayleigh Distributions

- Generate available steps from Rayleigh step-length distribution

- Compare with commonly used distributions (gamma, log-normal)

- Assess model fit using AIC and predictive performance

Key Findings: The Rayleigh distribution naturally accommodates irregular time intervals and showed advantages in precision and inference compared to traditional distributions [25].

Statistical Software and Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for SSF Implementation

| Tool Category | Specific Software/Package | Key Functionality | Application in SSF Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| R Packages | amt [23] |

SSF, RSF, movement analysis | Track manipulation, SSF implementation |

momentuHMM [23] |

HMM fitting | Behavioral state inference | |

glmmTMB, inlabru |

Advanced regression | Model fitting alternatives | |

| GIS Software | ArcGIS, QGIS, Raster | Spatial analysis | Environmental covariate processing |

| Programming | R, Python | Data manipulation | End-to-end analysis workflow |

| Specialized Tools | GME [24] | SSF implementation | Early SSF tool for GIS integration |

Data Requirements and Collection Technologies

GPS Tracking Technology: Modern wildlife tracking collars capable of high-frequency data collection (minutes to hours between fixes) with high spatial accuracy (e.g., GPS, satellite telemetry) [24] [9]. The choice of fix rate should align with the research question and the expected scale of animal decision-making [24].

Environmental Data Layers: Remote sensing products and geographic information systems (GIS) providing data on vegetation, topography, hydrology, human infrastructure, and climate variables at appropriate spatial and temporal resolutions [24] [23]. The resolution should match the scale of animal perception and movement capabilities.

Computational Infrastructure: Adequate computing resources for processing large movement datasets, storing environmental layers, and running computationally intensive statistical models, particularly for hierarchical or integrated SSF approaches [9] [27].

Advanced Methodological Considerations

Integrated Step-Selection Analysis (iSSA)

Integrated Step-Selection Analysis extends conventional SSFs by simultaneously estimating movement parameters and selection coefficients, thereby providing a more cohesive framework for understanding movement and habitat selection [26] [25]. This approach explicitly models how environmental covariates influence both movement characteristics (step lengths and turning angles) and habitat selection, offering a more mechanistic understanding of animal space use [26].

Numerical Integration Approaches

Traditional SSF estimation often relies on conditional logistic regression, which can be limiting for certain model formulations [27]. Numerical integration techniques, including Monte Carlo methods and quadrature approaches, offer alternative estimation strategies that provide greater flexibility in model specification and improved statistical inference [27]. These approaches explicitly distinguish between model formulation and inference technique, allowing researchers to compare different SSF formulations using standard model selection criteria like AIC [27].

Multi-Scale and Hierarchical Frameworks

Animal movement occurs across multiple spatial and temporal scales, necessitating approaches that can accommodate this complexity [24] [9]. Hierarchical frameworks that partition movement trajectories into nested behavioral modes and phases enable researchers to connect fine-scale movement decisions to broader-scale space use patterns [9]. These approaches are particularly valuable for forecasting how animals may respond to environmental changes across different organizational levels [9].

Step-Selection Functions provide a powerful and flexible framework for integrating animal movement with environmental selection, offering distinct advantages over traditional RSFs particularly for fine-scale analyses of movement- habitat interactions [24] [23] [25]. The integration of behavioral states through HMMs or behavior-specific SSFs further enhances our ability to understand the contextual nature of habitat selection [23] [26].

Future methodological developments will likely focus on improved computational efficiency for large datasets, enhanced incorporation of individual variability, more sophisticated approaches for defining availability, and better integration with population-level processes [9] [27]. As movement ecology continues to mature, the validation and comparison of different modeling approaches will be essential for advancing both methodological rigor and ecological understanding [23].