Beyond Symmetry: How Interaction Asymmetry is Reshaping Network Analysis in Drug Discovery

This article explores the critical shift from traditional, symmetric network metrics to the analysis of interaction asymmetry and its profound implications for biomedical research.

Beyond Symmetry: How Interaction Asymmetry is Reshaping Network Analysis in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article explores the critical shift from traditional, symmetric network metrics to the analysis of interaction asymmetry and its profound implications for biomedical research. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational concepts of asymmetric interactions—from evolutionary games to social and ecological networks—and details their methodological applications in predicting drug interactions and identifying novel targets. The content further addresses key challenges, including data heterogeneity and computational scalability, and provides guidance on validation strategies using domain-specific metrics. By synthesizing insights across these intents, the article demonstrates how embracing asymmetry offers a more nuanced, powerful, and biologically realistic framework for accelerating drug discovery and improving predictive accuracy.

From Symmetry to Asymmetry: Redefining Network Foundations in Biology

In the analysis of complex networks, from social systems to biological interactions, traditional metrics have long relied on a fundamental but often flawed assumption: that the relationships they measure are symmetric. These conventional approaches—including counts of publications and patents, neighborhood overlap in social networks, and simple citation indices—quantify interactions as if they are perceived equally by all participating entities. Yet, a growing body of research reveals that this assumption of symmetry frequently obscures more than it reveals, leading to incomplete assessments and flawed predictions across scientific domains. The limitations of these traditional metrics become particularly problematic in research fields where accurate relationship mapping directly impacts outcomes, such as in drug development where interaction predictability can mean the difference between therapeutic success and failure.

This article explores the emerging paradigm of interaction asymmetry and its critical role in understanding complex networks. We demonstrate through experimental data from diverse fields—including legal outcomes, scientific collaboration, and drug-drug interactions—how moving beyond symmetric metrics enables more accurate predictions and deeper insights. By examining specific methodological frameworks that successfully incorporate asymmetry, we provide researchers with practical tools for overcoming the limitations of traditional network analysis and unlocking more nuanced understanding of the systems they study.

Theoretical Foundation: From Symmetric Assumptions to Asymmetric Reality

The Flawed Legacy of Symmetric Metrics

Traditional network metrics have dominated scientific analysis despite their inherent limitations. As noted by the National Research Council, "currently available metrics for research inputs and outputs are of some use in measuring aspects of the American research enterprise, but are not sufficient to answer broad questions about the enterprise on a national level" [1]. These conventional approaches include bibliometrics (quantitative measures of publication quantity and dissemination), neighborhood overlap in social networks, and simple citation counts for scientific impact assessment. Their fundamental weakness lies in treating complex, directional relationships as if they are reciprocal and equally significant to all parties involved.

The assumption of symmetry is particularly problematic in social network analysis. As Granovetter's theory of strong and weak ties suggests, social connections vary significantly in their intensity and importance [2]. However, traditional implementations of this theory have relied on symmetric measures that assume if node A has a strong connection to node B, then node B must equally have a strong connection to node A. Recent research has revealed that this symmetrical framework fails to capture the true nature of most social interactions, leading to what one study describes as "inappropriate (i.e. symmetric instead of asymmetric) quantities used to study weight-topology correlations" [2].

The Emerging Paradigm of Interaction Asymmetry

Interaction asymmetry acknowledges that relationships in networks are rarely balanced or equally perceived. In coauthorship networks, for instance, the significance of a collaborative relationship can differ dramatically between senior and junior researchers, even when the formal connection appears identical [2]. This asymmetry arises from differences in network position, resources, expertise, and perceived value of the relationship from each participant's perspective.

The theoretical shift from symmetric to asymmetric analysis represents more than just a methodological adjustment—it constitutes a fundamental rethinking of how relationships operate in complex systems. Where symmetric approaches flatten and simplify, asymmetric analysis preserves and reveals the directional nuances that often determine actual outcomes. This paradigm recognizes that a connection's strength and meaning cannot be captured by a single value but must be understood through the potentially divergent perspectives of each participant in the relationship.

Quantitative Evidence: Measuring Symmetry's Shortcomings

Performance Comparison: Symmetric vs. Asymmetric Metrics

Table 1: Predictive Performance Comparison Across Domains

| Domain | Symmetric Metric | Performance | Asymmetric Metric | Performance | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Legal Outcome Prediction | Prestige-Based Ranking | 0.14 Kendall's τ | Outcome-Based AHPI Algorithm | 0.82 Kendall's τ | +485% [3] |

| Social Tie Strength Prediction | Neighborhood Overlap | Non-Monotonic U-shaped Relation | Asymmetric Neighborhood Overlap | Strictly Growing Relation | Qualitative Improvement [2] |

| Scientific Impact Assessment | Journal Impact Factor | Slow Accumulation | Social Network Metrics | Real-time Assessment | Temporal Advantage [4] |

| Drug-Drug Interaction | Traditional ML Features | Limited Knowledge Capture | Graph Neural Networks | Automated Feature Learning | Enhanced Robustness [5] |

Correlation Analysis: Traditional vs. Modern Metrics

Table 2: Metric Correlations in Scientific Impact Assessment

| Metric Type | Specific Metric | Correlation with Traditional SJR | Correlation with Social Media Presence | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Citation-Based | SJR (Scimago Journal Rank) | 1.00 | Moderate Positive | Slow accumulation, narrow audience [4] |

| Traditional Citation-Based | H-index | 0.89 (estimated) | Moderate Positive | Field-dependent, size-dependent [4] |

| Social Network-Based | Twitter Followers | Moderate Positive | 1.00 | Potential for manipulation [4] |

| Social Network-Based | Tweet Volume | Moderate Positive | 0.93 (estimated) | May not reflect engagement quality [4] |

The quantitative evidence clearly demonstrates the superiority of asymmetric approaches across multiple domains. In legal outcome prediction, the asymmetric heterogeneous pairwise interactions (AHPI) algorithm achieves a remarkable Kendall's τ of 0.82 in predicting litigation success, compared to a near-zero correlation for traditional prestige-based rankings [3]. This represents not just an incremental improvement but a fundamental shift in predictive capability.

Similarly, in social network analysis, the relationship between tie strength and neighborhood overlap follows a non-monotonic U-shaped pattern when measured with symmetric metrics, contradicting established theory. However, when analyzed with asymmetric neighborhood overlap, the expected strictly growing relationship emerges, confirming theoretical predictions [2]. This pattern repeats across domains, suggesting that asymmetric approaches consistently provide more theoretically coherent and practically useful results.

Experimental Protocols: Implementing Asymmetric Analysis

Asymmetric Heterogeneous Pairwise Interactions (AHPI) Algorithm

The AHPI ranking algorithm represents a sophisticated methodology for handling asymmetric interactions in litigation outcomes [3]. The protocol proceeds through these detailed steps:

Data Compilation: Assemble a comprehensive dataset of legal cases, extracting plaintiff and defendant law firms, case types, and binary outcomes (plaintiff victory = 1, defendant victory = 0).

Network Construction: Transform case data into a network of pairwise firm interactions, resulting in numerous pairwise interactions annotated with opposing firms, case type, and outcome.

Quality Filtering: Implement a Q-factor threshold (Q=30 in primary results) to iteratively remove low-activity firms until achieving a robust subnetwork with sufficient interactions per firm.

Model Initialization: Establish a Bayesian expectation-maximization framework with logistic prior over scores, accounting for M different case types.

Parameter Estimation: Fit K firm scores, M case-specific biases (εm), and M valence probabilities (qm) that represent how much rankings influence case outcomes for each type.

Validation: Reserve 20% of cases for out-of-sample evaluation, using the fitted model to predict outcomes based on score differentials between plaintiff and defendant firms.

This protocol successfully addresses the structural asymmetries in litigation, where defendants have significantly higher baseline win rates that vary substantially by case type (e.g., 86% for civil rights cases vs. 70% for contract cases) [3].

Asymmetric Neighborhood Overlap in Coauthorship Networks

For analyzing social and collaborative networks, the protocol for measuring asymmetric neighborhood overlap involves [2]:

Data Acquisition: Extract coauthorship data from comprehensive bibliographic databases (e.g., DBLP computer science bibliography), focusing on fields with substantial collaborative research.

Network Representation: Construct undirected coauthorship networks where nodes represent scientists and edges connect coauthors.

Tie Strength Quantification: Define asymmetric tie strength based on collaborative intensity from each scientist's perspective, typically normalized by their total collaborative output.

Neighborhood Analysis: Calculate asymmetric neighborhood overlap for each connection, recognizing that common neighbors may represent significantly different proportions of each scientist's total network.

Correlation Assessment: Examine the relationship between asymmetric tie strength and asymmetric neighborhood overlap, comparing results with traditional symmetric measures.

Model Validation: Apply the same methodology to multiple independent datasets and synthetic models of scientific collaboration to verify consistency of findings.

This approach reveals that "in order to better understand weight-topology correlations in social networks, it is necessary to use measures that formally take into account asymmetry of social interactions, which may arise, for example, from differences in ego-networks of connected nodes" [2].

Graph Neural Networks for Drug-Drug Interaction Prediction

In pharmaceutical applications, the protocol for predicting drug-drug interactions using graph neural networks involves [5]:

Molecular Representation: Represent drug compounds as molecular graphs where atoms serve as nodes and chemical bonds as edges.

Feature Initialization: Assign initial feature vectors to each atom based on chemical properties (e.g., atom type, charge, hybridization state).

Message Passing: Implement graph convolutional layers where nodes iteratively aggregate feature information from their neighbors, updating their representations based on these aggregated messages.

Subgraph Detection: Apply conditional graph information bottleneck principles to identify minimal molecular subgraphs that contain sufficient information for predicting interactions between drug pairs.

Interaction Prediction: Combine representations of two drug molecules using specialized neural network architectures designed to capture interaction effects.

Validation: Evaluate predictive performance on common DDI datasets using rigorous cross-validation and comparison with traditional machine learning approaches.

This method leverages the fundamental insight that "the core structure of a compound molecule depends on its interaction with other compound molecules" [5], necessitating an asymmetric, context-dependent analytical approach.

Visualization: Mapping Asymmetric Relationships

The Asymmetric Heterogeneous Pairwise Interactions Model

AHPI Model Architecture - This diagram illustrates the flow of information through the Asymmetric Heterogeneous Pairwise Interactions model, showing how case-type biases and firm scores combine to predict litigation outcomes.

Graph Neural Network for Drug-Drug Interactions

DDI Prediction Workflow - This diagram shows how graph neural networks process molecular structures of two drugs to predict their interactions, detecting core subgraphs that determine reactivity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| DBLP Computer Science Bibliography | Dataset | Provides coauthorship network data with temporal dimensions | Analyzing asymmetric collaboration patterns in scientific research [2] |

| Scimago Journal Rank (SJR) | Metric | Evaluates journal influence based on citation networks | Comparing traditional symmetric metrics with asymmetric alternatives [4] |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | Computational Framework | Learns representations of graph-structured data through message passing | Predicting drug-drug interactions by capturing molecular structure relationships [5] |

| Bradley-Terry Model | Statistical Framework | Models outcomes of pairwise comparisons with latent quality scores | Foundation for extending to asymmetric heterogeneous pairwise interactions [3] |

| Conditional Graph Information Bottleneck | Algorithmic Principle | Identifies minimal sufficient subgraphs for interaction prediction | Explaining essential molecular substructures in drug-drug interactions [5] |

| STAR METRICS Program | Data Infrastructure | Links research datasets for comprehensive analysis | Potential resource for future asymmetric research assessment [1] |

The tools and resources highlighted in Table 3 represent essential components for implementing asymmetric network analysis across research domains. For drug development professionals, graph neural networks and the conditional graph information bottleneck principle offer particularly valuable approaches for moving beyond traditional symmetric analysis of molecular interactions. These methods enable researchers to "find the minimum information containing molecular subgraph for a given pair of compound molecule graphs," which "effectively predicts the essence of compound molecule reactions, wherein the core structure of a compound molecule depends on its interaction with other compound molecules" [5].

For social and scientific network analysis, comprehensive datasets like the DBLP computer science bibliography provide the raw material for examining how asymmetric relationships operate in collaborative environments. When combined with statistical frameworks like the extended Bradley-Terry model, these resources enable researchers to quantify and predict outcomes based on directional relationship strengths rather than assuming symmetrical connections.

The evidence from multiple research domains converges on a singular conclusion: symmetric network metrics fall short because they fundamentally misrepresent the directional nature of real-world relationships. Whether in predicting legal outcomes, mapping scientific collaboration, or forecasting drug interactions, approaches that incorporate interaction asymmetry consistently outperform traditional symmetric methods. The assumption of symmetry, while computationally convenient, obscures crucial directional dynamics that often determine actual outcomes in complex systems.

For researchers and drug development professionals, embracing asymmetric analysis methods represents more than a technical adjustment—it offers a pathway to more accurate predictions, more effective interventions, and more nuanced understanding of the systems they study. By implementing the experimental protocols and tools outlined in this article, scientists can overcome the limitations of traditional network metrics and unlock deeper insights into the asymmetric relationships that shape our complex world. As research continues to demonstrate the superiority of these approaches, asymmetric analysis is poised to become the new standard for network science across disciplines.

Traditional network science has provided invaluable tools for mapping complex systems across biology, from molecular interactions to ecological communities. Conventional metrics often rely on static correlation networks and undirected edges, which capture co-occurrence but fundamentally ignore the directionality and power dynamics of relationships [6]. This static, symmetric view presents a critical limitation: it cannot decipher whether one element exerts a stronger influence over another, a phenomenon central to understanding hierarchical organization in biological systems, from cellular signaling cascades to drug-target interactions.

Interaction asymmetry emerges as a pivotal theoretical framework to address this gap. It is formally defined as the principle that "Parts of the same concept have more complex interactions than parts of different concepts" [7] [8]. This asymmetry provides a mathematical foundation for disentangling representations of underlying concepts (e.g., distinct biological pathways or drug mechanisms) and enables compositional generalization, allowing for predictions about system behavior under novel, out-of-domain perturbations [7]. This stands in stark contrast to traditional network metrics, which are often limited to describing the static structure of correlations without illuminating the causal, directional influences that drive system dynamics. This comparative guide objectively evaluates this emerging paradigm against established analytical models.

Theoretical Foundation of Interaction Asymmetry

The mathematical formalization of interaction asymmetry moves beyond zero- and first-order relationships, capturing higher-order complexities that define biological systems. The core principle is formalized via block diagonality conditions on the (n+1)th order derivatives of the generator function that maps latent concepts to the observed data [7] [8]. Different orders n correspond to different levels of interaction complexity:

- n=0 (No Interaction Asymmetry): Relies on independence of concepts. Prior works assuming statistical independence are recovered as a special case [8].

- n=1 (First-Order Asymmetry): Considers the complexity of first-order interactions (gradients). This unifies theories that require linear independence of concept representations [8].

- n=2 (Second-Order Asymmetry): Extends the principle to more flexible generator functions by analyzing second-order derivatives (Hessians), capturing more complex, non-linear relationships between components [7].

This formalism proves that interaction asymmetry enables both the identifiability of latent concepts and compositional generalization without direct supervision [8]. Practically, this theory suggests that to disentangle concepts, a model should penalize both its latent capacity and the interactions between concepts during decoding. A proposed implementation uses a Transformer-based VAE with a novel regularizer applied to the attention weights of the decoder, explicitly enforcing this asymmetry [7].

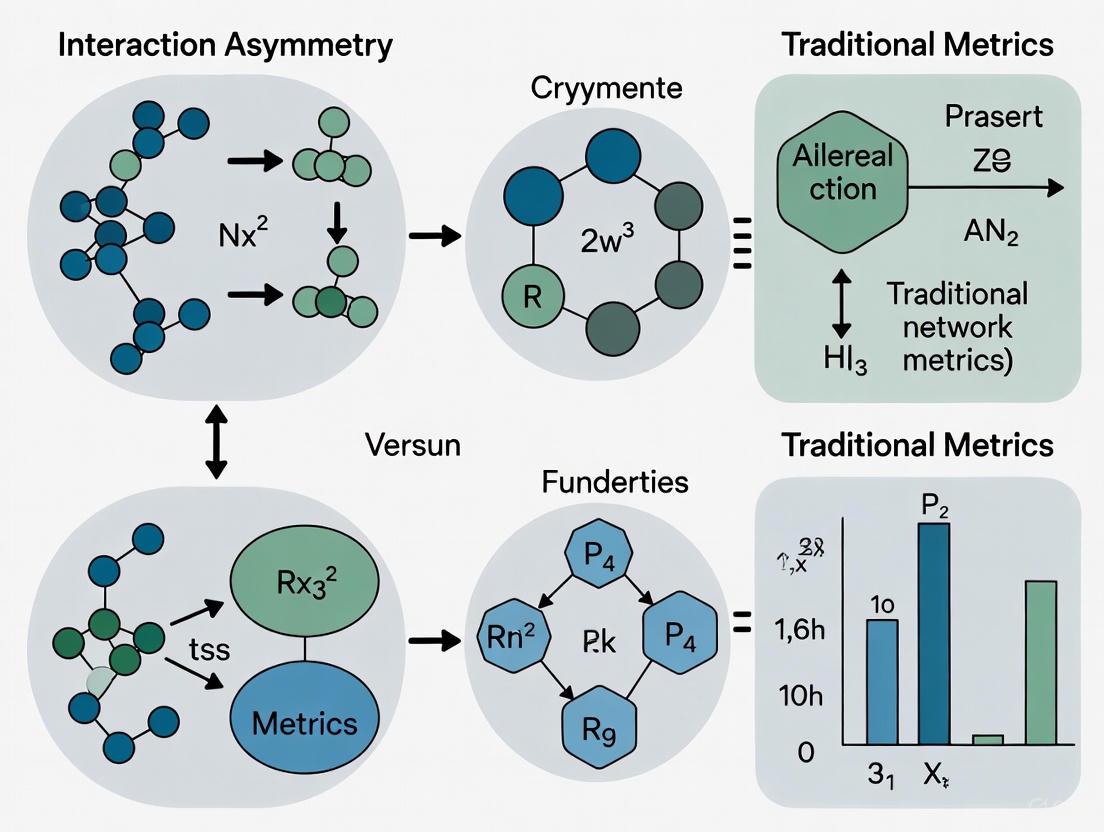

Visualizing the Principle of Interaction Asymmetry

The following diagram illustrates the core concept of interaction asymmetry, showing dense intra-concept interactions and sparse inter-concept interactions, leading to a block-diagonal structure in higher-order derivatives.

Comparative Analysis: Interaction Asymmetry vs. Traditional Network Models

This section provides a direct, data-driven comparison between modern frameworks implementing interaction asymmetry and traditional network inference models.

Experimental Protocol & Model Specifications

The comparative analysis draws on two primary sources of experimental data:

Transformer-VAE with Asymmetry Regularizer: Experimental data was derived from studies on synthetic image datasets consisting of objects [7] [8]. The core methodology involved:

- Model Architecture: A flexible Transformer-based Variational Autoencoder (VAE).

- Key Intervention: A novel regularizer applied to the attention weights of the decoder, designed to penalize latent capacity and interactions between concepts during decoding, thereby enforcing interaction asymmetry.

- Evaluation Metric: The model's ability to achieve object disentanglement in an unsupervised manner, measured against benchmarks that use explicit object-centric priors.

Dynamic Network Inference Models (LV vs. MAR): A separate, direct comparison of two dynamic network models was used to represent traditional metrics [6].

- Lotka-Volterra (LV) Models: Systems of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) designed to elucidate long-term dynamics of interacting populations. Parameters (interaction strengths) were inferred from time-series data using linear regression [6].

- Multivariate Autoregressive (MAR) Models: Statistical models conceived to study interacting populations and the stochastic structure of data. These were implemented with and without log transformation of data [6].

- Evaluation Context: Both models were assessed on synthetically generated data and real ecological datasets for their ability to fit data, capture underlying process dynamics, and infer correct network parameters.

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The table below summarizes the experimental outcomes from the cited studies, providing a quantitative basis for comparison.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Modeling Frameworks

| Model Feature | Transformer-VAE with Asymmetry Regularizer | Lotka-Volterra (LV) Models | Multivariate Autoregressive (MAR) Models |

|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Basis | Interaction Asymmetry & Higher-Order Derivatives [7] | Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs) [6] | Statistical Time-Series Analysis [6] |

| Core Strength | Unsupervised disentanglement & compositional generalization [8] | Capturing non-linear dynamics and long-term behavior [6] | Handling process noise and linear/near-linear dynamics [6] |

| Inference Clarity | Provable identifiability of concepts under asymmetry [8] | Superior for inferring interactions in non-linear systems [6] | Superior for systems with process noise and close-to-linear behavior [6] |

| Quantitative Result | Achieved comparable object disentanglement to models with explicit object-centric priors [7] | Generally superior in capturing network dynamics with non-linearities [6] | Better suited for analyses with process noise and close-to-linear behavior [6] |

| Key Limitation | Requires formalization of "concepts"; complexity of high-order derivatives | Can be mathematically complex for large networks; sensitive to parameter estimation | Mathematically equivalent to LV at steady state but may miss non-linearities [6] |

Visualizing the Comparative Experimental Workflow

The following diagram outlines the key stages of the experiments cited in the comparative analysis, highlighting the divergent approaches.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The experimental protocols for investigating interaction networks and asymmetry require specific computational and analytical tools. The following table details key resources.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item / Solution | Function in Research | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Transformer-based VAE | A flexible neural architecture for learning composable abstractions from high-dimensional data. | Implementation of the interaction asymmetry principle via regularization of decoder attention [7]. |

| Asymmetry Regularizer | A novel penalty on the attention weights of a decoder to enforce block-diagonality in concept interactions. | Used to penalize latent capacity and inter-concept interactions, guiding unsupervised disentanglement [7]. |

| Lotka-Volterra (LV) Models | A system of ODEs for modeling the dynamics of competing or interacting populations. | A traditional benchmark for inferring directed, asymmetric species interactions from ecological time-series data [6]. |

| Multivariate Autoregressive (MAR) Models | A statistical framework for modeling stochastic, linear temporal dependencies between multiple variables. | Used as a comparative model for network inference, particularly in systems with process noise [6]. |

| Synthetic Image Datasets | Customizable datasets containing composable objects, allowing for controlled evaluation. | Provides ground-truth for evaluating disentanglement and compositional generalization in model benchmarks [7] [8]. |

| Linear Regression Methods | A foundational statistical technique for estimating the parameters of a linear model. | Used for parameter inference (interaction strengths) in Lotka-Volterra models from time-series data [6]. |

The empirical evidence demonstrates that the principle of interaction asymmetry provides a mathematically rigorous and practically implementable framework for moving beyond the limitations of traditional, symmetric network metrics. By formally accounting for the inherent directionality and power imbalances in biological interactions—whether in molecular networks or between drug targets—this approach enables a deeper, more causal understanding of system dynamics. The ability to provably disentangle latent concepts and generalize to unseen combinations in an unsupervised manner [7] [8] positions interaction asymmetry as a foundational element for the next generation of analytical tools in computational biology and drug development. While traditional models like LV and MAR remain valuable for specific dynamic regimes [6], the paradigm of interaction asymmetry offers a unifying principle for achieving compositional generalization, a critical capability for predicting cellular response to novel therapeutic interventions.

Evolutionary game theory provides a powerful mathematical framework for understanding the evolution of social behaviors in populations of interacting individuals. A long-standing convention within this field has been the assumption of symmetric interactions, where players are distinguished only by their strategies [9]. However, biological interactions in nature—from conflicts between animals to cellular processes relevant to drug action—are fundamentally asymmetric. This review explores the theoretical precedents established by models of asymmetric evolutionary games, comparing their dynamics and outcomes with traditional symmetric frameworks. We situate this analysis within a broader thesis on interaction asymmetry, arguing that these models provide a more nuanced and biologically realistic foundation for research than approaches relying solely on traditional network metrics.

Theoretical Foundations of Asymmetry in Evolutionary Games

Defining Asymmetry and its Biological Origins

In evolutionary game theory, an asymmetric interaction occurs when the payoff for an individual depends not only on the strategies involved but also on inherent differences between the players [9]. Such differences render interactions fundamentally non-identical, a condition that is the rule rather than the exception in biological systems.

The theoretical development of asymmetric games has crystallized around two broad classes:

- Ecological Asymmetry: This results from variation in the environments or spatial locations of the players [9]. In a structured population, the payoff for a player at location i against a player at location j is defined by a matrix Mij, meaning the outcome of an interaction is tied to environmental context.

- Genotypic Asymmetry: This arises from players differing in baseline characteristics, such as size, strength, or genetic makeup, which influence their payoffs independently of their chosen strategy [9]. A "strong" cooperator might provide a greater benefit or incur a lower cost than a "weak" cooperator.

These forms of asymmetry cover a wide range of natural phenomena, including phenotypic variations, differential access to resources, social role assignments (e.g., parent-offspring), and the effects of past interaction histories [9].

Formal Representation: From Symmetric to Bimatrix Games

The classical symmetric social dilemma is represented by a single payoff matrix where the game's rules are identical for all players.

Table 1: Payoff Matrix for a General Symmetric Game

| Focal Player / Opponent | Cooperate | Defect |

|---|---|---|

| Cooperate | R, R | S, T |

| Defect | T, S | P, P |

R = Reward for mutual cooperation; S = Sucker's payoff; T = Temptation to defect; P = Punishment for mutual defection. The Prisoner's Dilemma requires T > R > P > S.

In contrast, asymmetric interactions are formally modeled as bimatrix games [9]. In the classic Battle of the Sexes game, for example, males and females constitute distinct populations with different strategy sets and payoff matrices [10]. The payoff for a faithful male interacting with a coy female is distinct from the payoff for that same female interacting with the male, and these payoffs are not interchangeable. This framework allows the assignment of different roles and different consequences for players in different positions.

Comparative Analysis: Asymmetric vs. Symmetric Game Dynamics

The introduction of asymmetry fundamentally alters the evolutionary dynamics and stable outcomes of games, leading to predictions that diverge significantly from symmetric models.

Table 2: Comparison of Symmetric and Asymmetric Game Properties

| Feature | Symmetric Games | Asymmetric Games |

|---|---|---|

| Representation | Single payoff matrix | Two payoff matrices (bimatrix) |

| Player Roles | Identical | Distinct (e.g., Male/Female) |

| Evolutionarily Stable Strategy (ESS) | Can be a mixed strategy | Selten's Theorem: ESS is always a pure strategy [11] |

| Interior Equilibrium Stability | Can be stable | Typically unstable, leads to cyclical dynamics [10] |

| Modeled Biological Conflict | Basic intraspecies competition | Role-based conflicts, parent-offspring, host-parasite |

Stability and the Nature of Equilibria

A critical difference lies in the stability of equilibria. A foundational result, Selten's Theorem, states that for asymmetric games, an evolutionarily stable strategy (ESS) must be a pure strategy—meaning players do not randomize but choose a single course of action [11]. This contrasts with symmetric games like Hawk-Dove, where a stable mixed equilibrium can exist [12].

Furthermore, in two-phenotype bimatrix games like the Battle of the Sexes, any unique interior equilibrium is inherently unstable, resulting in population dynamics that cycle perpetually around this point rather than converging to it [10]. This cyclicality provides a theoretical basis for the maintenance of phenotypic variation over time, a phenomenon that can be challenging to explain with symmetric models.

The Impact of Individual Volition and Non-Uniform Interaction

Recent theoretical work has incorporated the concept of individual volition, where players can preferentially choose interaction partners based on self-interest. This represents a specific and biologically relevant form of asymmetry. In the Battle of the Sexes, for instance, both faithful and philandering males prefer to mate with "fast" females, while both coy and fast females prefer "faithful" males [10].

When models account for this preference-based asymmetry, the dynamics can stabilize. A population with an even sex ratio can converge to a stable equilibrium where faithful males and coy females coexist with philandering males and fast females, a outcome not possible under classic bimatrix assumptions with uniform random interaction [10]. This demonstrates that the specific structure of asymmetry is critical in determining evolutionary outcomes.

Methodological Protocols for Studying Asymmetry

Modeling Framework for Structured Populations

The study of asymmetric games often requires a structured population model, where individuals occupy nodes on a network.

- Population Structure: Represent the population as a network of N players, with an adjacency matrix (w_ij) defining links between individuals [9].

- Payoff Calculation: Each player interacts with all its neighbors. The total payoff from these interactions is calculated using the appropriate bimatrix payoffs based on player roles or locations.

- Selection and Fitness: The total payoff is multiplied by a selection intensity (β ≥ 0) and converted to fitness [9].

- Update Rules: The population state is updated using rules such as:

- Birth-Death: A player is selected for reproduction proportional to fitness; a random neighbor is replaced by an offspring inheriting the parent's strategy [9].

- Death-Birth: A player is randomly selected for death; neighbors compete to fill the vacancy with probability proportional to their fitness.

Analyzing Specialization in Interaction Networks

The move from binary to weighted network analysis is a key methodological shift that parallels the shift from symmetric to asymmetric games.

- Data Collection: Collect quantitative data on interaction frequencies (e.g., pollination visits, drug-target binding affinities) rather than mere presence/absence [13].

- Metric Calculation: Calculate weighted network metrics (e.g., weighted connectivity, interaction strength asymmetry) which retain information on the strength and direction of dependencies.

- Null Model Testing: Compare observed metrics against those generated from null models that account for neutral interactions and sampling biases. This controls for the fact that rarely observed species are inevitably misclassified as "specialists" [14].

- Interpretation: A finding of higher-than-expected reciprocal specialization (exclusiveness) after controlling for neutral effects suggests a tighter coevolution and lower ecological redundancy, consistent with the outcomes of asymmetric evolutionary games [14].

Visualization of Core Concepts

The following diagram illustrates the logical structure and key outcomes of asymmetric evolutionary game theory as discussed in this review.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for Asymmetric Game and Network Analysis

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Graph Theory Software (e.g.,igraph, NetworkX) | Used to construct, visualize, and analyze population structures and interaction networks, calculating key topological metrics [15]. |

| Evolutionary Simulation Platforms (Custom code in R/Python) | Enables implementation of agent-based models in structured populations with asymmetric payoff matrices and update rules (e.g., Birth-Death) [9]. |

| Bioactivity Databases (e.g., ChEMBL, DrugBank) | Provide curated data on drug-target interactions, which can be modeled as weighted, asymmetric networks to identify multi-target therapies [15] [16]. |

| Biological Interaction Databases (e.g., STRING, DisGeNET) | Supply data on protein-protein interactions and gene-disease associations, forming the basis for constructing and validating genotypic asymmetric models [15]. |

The theoretical precedents for asymmetric populations in evolutionary game theory mark a significant departure from classical symmetric models. Asymmetric games, formalized as bimatrix games and incorporating ecological and genotypic variation, provide a more robust framework for understanding real-world biological conflicts, from behavioral ecology to cellular and molecular interactions. The core findings—that stable equilibria are pure rather than mixed, that dynamics are often cyclical, and that individual volition can stabilize outcomes—offer profound insights for the field of network pharmacology. By moving beyond traditional, often binary network metrics to embrace the weighted and asymmetric nature of biological interactions, researchers in drug development can better map the complex landscape of drug-target interactions, identify synergistic multi-target therapies, and ultimately improve predictive models for therapeutic efficacy and safety.

Traditional social network analysis has often relied on the implicit assumption of symmetric interactions between connected nodes. Under this paradigm, measures such as the number of common neighbors or neighborhood overlap treat relationships as mutually equivalent, failing to capture the fundamental asymmetry of social ties [17]. This perspective has proven particularly limiting in coauthorship networks, where previous research mistakenly suggested these networks contradicted Granovetter's strength of weak ties hypothesis [17] [18].

The emerging research on interaction asymmetry challenges this symmetric worldview. In coauthorship networks with fat-tailed degree distributions, the ego-networks of two connected nodes may differ considerably [17]. Their common neighbors can represent a significant portion of the neighborhood for one node while being negligible for the other, creating fundamentally different perceptions of tie strength from each end of the connection [17]. This asymmetry perspective reveals that observed absolute tie strength represents a compromise between the relative strengths perceived from both nodes [17] [18].

This article examines how formally incorporating interaction asymmetry into network measures provides superior link predictability compared to traditional symmetric metrics, with particular relevance for scientific collaboration and drug discovery networks.

Theoretical Framework: From Symmetric to Asymmetric Measures

The Limitations of Traditional Symmetric Metrics

Traditional network analysis has predominantly utilized symmetric measures to characterize social ties. The table below summarizes key traditional metrics and their limitations when applied to asymmetric social contexts:

Table 1: Traditional Symmetric Metrics and Their Limitations

| Metric | Calculation | Limitations in Social Context |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Common Neighbors | Count of nodes connected to both focal nodes | Fails to account for different neighborhood sizes [17] |

| Neighborhood Overlap | ∣A∩B∣/∣A∪B∣ | Treats connection equally from both perspectives [17] |

| Adamic-Adar Index | ∑z∈A∩B1/log(degree(z)) | Assumes symmetric contribution of common neighbors [17] |

| Jaccard Coefficient | ∣A∩B∣/∣A∪B∣ | Does not consider relative importance of neighbors [17] |

These symmetric approaches perform poorly in coauthorship networks, often showing non-monotonic, U-shaped relationships between tie strength and neighborhood overlap that appear to contradict established social theory [17].

The Asymmetric Measures Framework

The asymmetric approach introduces directionality to social ties even in undirected networks through two key innovations:

Asymmetric Neighborhood Overlap: This measure calculates overlap from the perspective of each node separately, defined as the number of common neighbors divided by the degree of the focal node [17]. For a link between nodes A and B:

- ANOA→B = ∣neighbors(A) ∩ neighbors(B)∣ / ∣neighbors(A)∣

- ANOB→A = ∣neighbors(A) ∩ neighbors(B)∣ / ∣neighbors(B)∣

Asymmetric Tie Strength: This recognizes that the perceived strength of a connection may differ between the two connected nodes based on their relative positions in the network [17].

The conceptual relationship between these symmetric and asymmetric approaches can be visualized as follows:

Diagram 1: Conceptual Framework of Network Analysis Approaches

Experimental Protocols for Asymmetry Research

Network Construction and Data Preparation

Research on asymmetric link predictability typically follows a structured experimental protocol beginning with network construction:

Data Source Selection: Studies typically utilize large-scale coauthorship databases such as the DBLP computer science bibliography or other disciplinary databases that track scientific collaborations over extended periods [17]. These datasets provide temporal collaboration records that can be aggregated into cumulative networks.

Network Representation: Coauthorship networks are constructed as undirected graphs where:

- Nodes represent individual researchers

- Edges represent coauthored publications between researchers

- Edge weights typically represent collaboration frequency or number of joint publications [17]

Network Filtering: To ensure analytical integrity, researchers typically:

- Apply time windowing to study network evolution

- Remove isolated nodes and small disconnected components

- Implement minimum activity thresholds for node inclusion

Measuring Asymmetric Properties

The core experimental measurements focus on quantifying asymmetric properties:

Degree Asymmetry Calculation: For each connected node pair (A,B), compute the degree asymmetry ratio as ∣degree(A) - degree(B)∣ / max(degree(A), degree(B)) [17].

Asymmetric Neighborhood Overlap Measurement: Calculate ANO values in both directions for each edge and compute the absolute difference to quantify directionality [17].

Tie Strength Assessment: Define tie strength using collaboration intensity measures such as coauthored publication count, then correlate with asymmetric metrics [17].

The experimental workflow for investigating asymmetric link predictability follows a systematic process:

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Link Prediction Research

Validation Methodologies

Studies typically employ rigorous validation methods:

Temporal Validation: Networks are divided into training (earlier time period) and testing (later time period) sets to evaluate predictive accuracy for future collaborations [17].

Cross-Validation: k-fold cross-validation techniques assess model robustness, especially for smaller networks [17].

Baseline Comparison: Proposed asymmetric measures are compared against traditional symmetric benchmarks using standardized evaluation metrics including AUC-ROC, precision-recall curves, and top-k predictive accuracy [17].

Comparative Performance Analysis

Quantitative Comparison of Prediction Accuracy

Empirical studies across multiple coauthorship networks demonstrate the superior performance of asymmetric measures:

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Link Prediction Methods in Coauthorship Networks

| Prediction Method | Network Type | AUC-ROC Score | Precision @ Top-100 | Granovetter Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Common Neighbors | DBLP Network | 0.72 | 0.15 | Non-monotonic/U-shaped [17] |

| Adamic-Adar Index | DBLP Network | 0.75 | 0.18 | Non-monotonic/U-shaped [17] |

| Resource Allocation | DBLP Network | 0.81 | 0.24 | Weak positive [18] |

| Asymmetric Neighbor Overlap | DBLP Network | 0.89 | 0.31 | Strong positive (power-law) [17] [18] |

| Asymmetric Tie Strength | DBLP Network | 0.87 | 0.29 | Strong positive (power-law) [17] [18] |

The performance advantage of asymmetric approaches is consistent across different network scales and disciplines, having been validated in physics, biology, and cross-disciplinary coauthorship networks [17].

Resolving Theoretical contradictions

The asymmetric approach resolves the apparent contradiction between coauthorship networks and Granovetter's strength of weak ties hypothesis:

Table 3: How Asymmetry Resolves Theoretical Conflicts

| Theoretical Expectation | Symmetric Measure Result | Asymmetric Measure Result | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strength increases with embeddedness | U-shaped/non-monotonic relationship [17] | Power-law positive relationship [17] [18] | Symmetric measures obscure the underlying correlation |

| Weak ties bridge disconnected groups | Poor performance in identifying bridges [17] | Improved bridge identification [17] | Asymmetry captures different roles in network structure |

| Social bow-tie structure | Limited explanatory power [17] | High explanatory power [17] | Formalizes the social bow-tie concept quantitatively |

Application in Drug Discovery and Development

The implications of asymmetric link prediction extend to pharmaceutical research, where collaboration patterns influence discovery outcomes:

Analyzing Scientific Collaboration in Drug Discovery

Bibliometric analyses reveal distinctive collaboration patterns in AI-driven drug discovery research, with 28.06% international collaboration rate among publications and prominent institutions including Chinese Academy of Sciences and University of California systems leading productivity [19]. Understanding the asymmetric nature of these collaborations can optimize knowledge flow within and between organizations.

Social network analysis of open source drug discovery initiatives demonstrates how network structures conducive to innovation can be deliberately designed rather than emerging organically [20]. Asymmetric measures help identify key contributors whose connections disproportionately impact information dissemination.

Strategic Implications for Research Management

Research Portfolio Optimization: Pharmaceutical companies can apply asymmetric link prediction to identify emerging collaborations likely to produce high-impact research, directing funding and partnership opportunities more effectively [21].

Key Opinion Leader Identification: Rather than relying solely on publication counts or traditional centrality measures, asymmetric network analysis can detect researchers whose influence exceeds their apparent connectivity [21].

Open Innovation Management: For open source drug discovery projects, understanding asymmetric ties helps balance self-organization with strategic direction, addressing critical research questions about how such projects scale and self-organize [20].

Research Reagents: Analytical Tools for Asymmetry Studies

Researchers investigating asymmetric link predictability require both conceptual and computational tools:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Asymmetry Studies

| Research Reagent | Function/Purpose | Example Implementations |

|---|---|---|

| Coauthorship Datasets | Provide empirical network data for validation | DBLP, PubMed, Web of Science bibliographic records [17] [19] |

| Network Analysis Libraries | Calculate symmetric and asymmetric metrics | NetworkX, igraph, custom Python/R scripts [17] |

| Null Model Frameworks | Establish statistical significance of results | Maximum-entropy models, configuration models [22] |

| Visualization Tools | Represent asymmetric relationships in networks | Gephi, Cytoscape, VOSviewer [19] |

| Temporal Analysis Methods | Validate predictive accuracy over time | Time-series cross-validation, sliding window approaches [17] |

The evidence from social and coauthorship networks demonstrates that incorporating interaction asymmetry substantially improves link predictability compared to traditional symmetric metrics. This approach not only provides technical advantages for predicting future collaborations but also resolves theoretical contradictions that have persisted in social network analysis.

For drug discovery professionals and research managers, these findings offer practical tools for optimizing collaboration networks, identifying influential researchers, and strategically allocating resources based on a more sophisticated understanding of scientific social dynamics. The integration of asymmetric measures into network analysis platforms represents a promising direction for enhancing research productivity and innovation in scientifically intensive fields.

The perspective outlined also rationalizes the unexpectedly strong performance of certain existing metrics like the resource allocation index, suggesting they indirectly capture asymmetric properties through their mathematical formulation [18]. This understanding paves the way for designing next-generation network measures that explicitly incorporate asymmetry principles for enhanced analytical capability across diverse social and scientific collaboration contexts.

The study of ecological networks has profoundly influenced how we understand complex systems across multiple disciplines, including biomedical research. The concept of probabilistic and spatiotemporally variable interactions represents a paradigm shift from static, deterministic network models to dynamic frameworks that account for inherent uncertainty and scale-dependence in biological systems [23]. This perspective is particularly relevant for drug discovery, where traditional reductionist approaches often fail to capture the emergent properties of complex biological networks. Ecological research demonstrates that systems studied at small scales may appear considerably different in composition and behavior than the same systems studied at larger scales, creating significant challenges for extrapolating findings across spatial and temporal dimensions [23]. The integration of interaction asymmetry—where the strength and effect of relationships differ directionally—provides a more nuanced understanding of network dynamics than traditional symmetric metrics alone, offering valuable insights for analyzing pharmacological and disease networks.

Comparative Framework: Traditional Metrics vs. Interaction Asymmetry

Fundamental Conceptual Differences

Ecological network analysis has evolved from simple binary representations to sophisticated weighted frameworks that capture interaction strengths and directional dependencies. Binary networks record only the presence or absence of interactions between species, while weighted networks incorporate continuous measures of interaction strength or frequency [13]. This distinction is crucial for understanding the limitations of traditional metrics and the advantages of asymmetric analysis.

Traditional network metrics often assume symmetry and homogeneity, focusing on topological properties like connectivity patterns without considering variation in interaction intensities. In contrast, interaction asymmetry explicitly recognizes that relationships in biological systems are frequently unbalanced—for example, in mutualistic networks, one species may depend strongly on another while receiving only weak dependence in return [13]. This ecological insight directly translates to drug-target interactions, where a drug might strongly inhibit a protein while that protein's function has minimal feedback effect on the drug's efficacy.

Empirical Comparisons and Correlation Patterns

Research comparing binary and weighted ecological networks reveals both correlations and critical divergences in metric performance:

Table 1: Comparison of Network Metrics Across Representation Types

| Network Metric Category | Performance in Binary Networks | Performance in Weighted Networks | Correlation Strength |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specialization Indices | Limited resolution | Captures intensity variation | Moderate |

| Nestedness Patterns | Identifies basic structure | Reveals strength gradients | Strong |

| Asymmetry Measures | Underestimates directional bias | Quantifies interaction imbalance | Weak to Moderate |

| Modularity Analysis | Detects community boundaries | Identifies functional compartments | Strong |

Studies examining 65 ecological networks found "a positive correlation between BN and WN for all indices analysed, with just one exception," suggesting that binary networks can provide valid information about general trends despite their simplified structure [13]. However, the same research indicates that weighted networks provide superior insights for understanding asymmetry and specialization, which are fundamental to probabilistic interaction models.

Methodological Approaches: Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Data Sourcing and Curation Protocols

Research into probabilistic interactions requires integration of diverse data types from multiple sources. For ecological studies, this involves standardized protocols for field data collection across spatiotemporal gradients, while drug discovery applications leverage publicly available biomedical databases:

Table 2: Essential Data Sources for Network Construction

| Database Name | Data Type | Application in Network Analysis | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| CHEMBL [15] | Chemical compounds | Drug-target interaction prediction | Bioactivity data, target information |

| PubChem [15] | Small molecules | Chemical similarity networks | Structures, physical properties, biological activities |

| DrugBank [15] | Pharmaceuticals | Drug-disease association networks | Approved/experimental drugs, target data |

| DisGeNET [15] | Disease-gene associations | Disease network construction | Human genes, diseases, associations |

| STRING [15] | Protein-protein interactions | Molecular pathway networks | Functional partnerships, evidence scores |

Critical to this process is rigorous data curation, which must address "chemical, biological, and item identification aspects" to ensure reliability, including standardization of chemical structures, assessment of biological data variability, and correction of misspelled or mislabeled compounds [15].

Statistical Framework for Spatiotemporal Variability

Analyzing probabilistic interactions requires specialized statistical approaches that account for heterogeneity across scales. The central challenge lies in the "spatiotemporal variability of ecological systems," which refers to how systems change across space and time, distinct from compositional variability (differences in entities and causal factors) [23]. Methodological protocols must address:

- Multi-scale sampling designs that capture variation across relevant spatial and temporal dimensions

- Hierarchical modeling approaches that separate process variance from observation error

- Bayesian inference frameworks that quantify uncertainty in parameter estimates

- Network link prediction methods that handle sparse, heterogeneous data [24]

For drug discovery applications, these protocols adapt to incorporate biomedical data specificities, such as clinical trial results, adverse event reports, and genomic datasets like the Library of Integrated Network-based Cellular Signatures (LINCS) [24].

Visualization Framework for Probabilistic Interactions

The following workflow diagram illustrates the experimental protocol for analyzing probabilistic and spatiotemporal interactions in ecological and pharmacological contexts:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Implementing research on probabilistic interactions requires specialized computational and analytical resources. The following toolkit outlines essential solutions for researchers in this field:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Network Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Primary Function | Application Context | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prone [24] | Network embedding and link prediction | Drug-target interaction prediction | Captures network structure in low-dimensional space |

| ACT [24] | Similarity-based inference | Drug-drug interaction prediction | Utilizes topological similarity measures |

| LRW₅ [24] | Random walk algorithm | Disease-gene association prediction | Models local network connectivity |

| NRWRH [24] | Heterogeneous network analysis | Multi-type node relationships | Integrates diverse node and relationship types |

| DTINet [24] | Network integration pipeline | Drug-target interaction prediction | Combines heterogeneous data sources |

| Wine [13] | Nestedness estimation | Network structure analysis | Weighted-interaction nestedness estimator |

Application Domains: From Ecological Insights to Drug Discovery

Network-Based Drug Discovery Framework

The principles of probabilistic and asymmetric interactions find direct application in pharmaceutical research through network-based drug discovery approaches. These methods "model drug-target interactions (DTI) as networks between two sets of nodes: the drug candidates, and the entities affected by the drugs (i.e. diseases, genes, and other drugs)" [24]. This framework enables several critical applications:

- Drug-target interaction prediction: Identifying which drugs will affect specific proteins, supporting drug repurposing efforts

- Drug-drug side effect prediction: Forecasting adverse interactions between drug combinations

- Disease-gene association prediction: Determining which diseases affect particular genes

- Disease-drug association prediction: Connecting pharmaceutical and natural compounds to disease treatments [24]

These applications demonstrate how ecological concepts of asymmetric, probabilistic interactions translate directly to biomedical challenges, addressing the "expensive, time-consuming, and costly" nature of traditional drug discovery [24].

Comparative Performance in Prediction Tasks

Experimental evaluations of network-based approaches demonstrate their utility for pharmacological prediction tasks. One comprehensive study applied "32 different network-based machine learning models to five commonly available biomedical datasets, and evaluated their performance based on three important evaluations metrics namely AUROC, AUPR, and F1-score" [24]. The findings identified "Prone, ACT and LRW₅ as the top 3 best performers on all five datasets," validating the utility of network-based approaches for drug discovery applications [24].

The following diagram illustrates how ecological concepts of probabilistic interactions translate to drug discovery applications through network-based link prediction:

The study of probabilistic and spatiotemporally variable interactions in ecology provides powerful conceptual frameworks and methodological approaches for addressing complex challenges in drug discovery and network medicine. By recognizing the inherent asymmetry in biological interactions and accounting for spatiotemporal variability, researchers can develop more predictive models of drug-target interactions, identify novel therapeutic applications for existing drugs, and anticipate adverse drug interactions. The integration of these ecological insights with network-based machine learning approaches represents a promising frontier in computational drug discovery, enabling researchers to navigate the complexity of biological systems with greater precision and efficacy. As these interdisciplinary approaches mature, they will increasingly bridge the gap between ecological theory and pharmaceutical application, ultimately enhancing the efficiency and success of drug development pipelines.

Leveraging Asymmetry: Methodologies for Drug Target Identification and DDI Prediction

Network-Based Multi-Omics Integration for Target Identification

The identification of robust drug targets is a fundamental challenge in modern therapeutic development. While single-omics technologies have provided valuable insights, they often fail to capture the complex, multi-layered nature of disease mechanisms [25]. Network-based multi-omics integration has emerged as a transformative approach that systematically combines diverse molecular datasets within the framework of biological networks, enabling a more holistic understanding of disease pathogenesis and revealing novel therapeutic targets [26]. This paradigm shift from reductionist to systems-level analysis aligns with the recognition that diseases rarely result from single molecular defects but rather from perturbations in complex interconnected networks [26] [27].

This guide objectively compares the performance of predominant network-based multi-omics integration methods, with particular emphasis on their application to drug target identification. The analysis is framed within an important methodological evolution: the transition from traditional network metrics (which often prioritize highly connected nodes) to approaches that capture interaction asymmetry (which account for directional regulatory influence and context-specific relationships). This distinction is critical for identifying therapeutically actionable targets, as the most biologically relevant nodes are not necessarily the most highly connected ones in biological networks [26] [28].

Methodological Approaches and Comparative Analysis

Classification of Network-Based Multi-Omics Integration Methods

Network-based multi-omics integration methods can be systematically categorized into four primary approaches based on their underlying algorithmic principles and data integration strategies [26].

Table 1: Classification of Network-Based Multi-Omics Integration Methods

| Method Category | Core Principle | Primary Applications in Drug Discovery | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Network Propagation/Diffusion | Uses algorithms to simulate "flow" of information through biological networks to identify regions significantly associated with disease signals [26] [27]. | Disease gene prioritization, drug target identification, drug repurposing [27] [29]. | Effectively captures both direct and indirect associations; robust to incomplete network data. |

| Similarity-Based Approaches | Constructs and fuses Patient Similarity Networks (PSN) derived from multiple omics datasets to identify patient subgroups or biomarkers [30]. | Clinical outcome prediction, patient stratification, biomarker discovery [30]. | Handles heterogeneity across omics types effectively; reduces dimensionality. |

| Graph Neural Networks | Applies deep learning architectures to graph-structured data to learn node embeddings that integrate both network topology and node features [26]. | Drug response prediction, drug-target interaction prediction, novel target identification [26] [31]. | Captures complex non-linear relationships; integrates network structure with node attributes. |

| Network Inference Models | Infers causal or regulatory relationships between biomolecules from multi-omics data to construct context-specific networks [28]. | Mechanism of action studies, pathway elucidation, identification of master regulators [28] [25]. | Generates mechanistic insights; can reveal causal relationships rather than correlations. |

Performance Comparison Across Drug Discovery Applications

The performance of network-based integration methods varies significantly across different drug discovery applications. The following comparison synthesizes evidence from recent studies implementing these approaches.

Table 2: Performance Comparison Across Drug Discovery Applications

| Application Domain | Method Category | Reported Performance | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neurodegenerative Disease Target Identification | Network Propagation with Deep Learning | Identified 105 putative ALS-associated genes enriched in immune pathways (T-cell activation: q=1.07×10⁻¹⁰) [27]. | Integration of brain x-QTLs (eQTL, pQTL, sQTL, meQTL, haQTL) with protein-protein interaction network; validation against DisgeNET (p=0.008) and GWAS Catalog (p=0.032) [27]. |

| Clinical Outcome Prediction in Oncology | Similarity Network Fusion (SNF) | Network-level fusion outperformed feature-level fusion for multi-omics integration; achieved higher accuracy in predicting neuroblastoma survival [30]. | Analysis of two neuroblastoma datasets (SEQC: 498 samples; TARGET: 157 samples); SNF integrated gene expression and DNA methylation data; DNN classifiers with network features [30]. |

| Infectious Disease Severity Stratification | Multi-layer Network with Random Walk | Identified phase-specific biosignatures for COVID-19; revealed STAT1, SOD2, and specific lipids as hubs in severe disease network [29]. | Integrated transcriptomics, metabolomics, proteomics, and lipidomics from multiple studies; constructed unified COVID-19 knowledge graph; applied random walk with restart algorithm [29]. |

| Target Identification Through Temporal Dynamics | Longitudinal Network Integration | Captured dynamic, time-dependent interactions between omics layers; identified key regulators in system development [28]. | Applied to multi-omics time-course data; used Linear Mixed Model Splines to cluster temporal patterns; combined inferred and known relationships in hybrid networks [28]. |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol 1: Network Propagation for Neurodegenerative Disease Target Identification

The following workflow outlines the methodology used for identifying drug targets in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) through network-based multi-omics integration [27].

Experimental Workflow

Diagram 1: ALS Target Identification Workflow

Step-by-Step Protocol

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

- Collect genome-wide association study (GWAS) data for ALS, focusing on non-coding loci with significant disease associations [27].

- Generate or acquire human brain quantitative trait loci (x-QTL) profiles, including:

- Expression QTL (eQTL)

- Protein QTL (pQTL)

- Splicing QTL (sQTL)

- Methylation QTL (meQTL)

- Histone acetylation QTL (haQTL)

- Curate protein-protein interaction (PPI) data from reference databases (e.g., BioGRID) to construct the human interactome [27] [28].

Network Construction and Functional Module Detection

- Construct a comprehensive PPI network representing the human interactome.

- Apply unsupervised deep learning to partition the PPI network into distinct functional modules based on topological features [27].

- Annotate network modules using Gene Ontology (GO) terms to establish functional relationships.

Multi-Omics Integration and Gene Scoring

- For each x-QTL type, compute gene-level scores based on functional similarity to known ALS-associated loci within the network context.

- Integrate scores across all five x-QTL types through weighted summation to generate a comprehensive prioritization score for each gene [27].

- Apply Z-score cutoff (typically >2-3) to identify high-confidence ALS-associated genes.

Validation and Experimental Confirmation

- Validate predicted ALS-associated genes against independent databases (DisGeNET, Open Targets, GWAS Catalog) using Fisher's exact test [27].

- Perform pathway enrichment analysis to establish biological relevance of identified gene sets.

- Conduct preclinical validation of top-prioritized targets using appropriate disease models.

Protocol 2: Patient Similarity Network Fusion for Clinical Outcome Prediction

This protocol details the application of similarity network fusion for predicting clinical outcomes in neuroblastoma patients using multi-omics data [30].

Experimental Workflow

Diagram 2: Clinical Outcome Prediction Workflow

Step-by-Step Protocol

Multi-Omics Data Collection and Processing

- Obtain matched multi-omics datasets (e.g., transcriptomics and DNA methylation) from patient cohorts with associated clinical outcomes [30].

- For neuroblastoma, utilize datasets from TARGET project (157 high-risk samples with RNA-seq and methylation data) and SEQC project (498 samples with microarray and RNA-seq data) [30].

- Perform standard normalization and quality control procedures specific to each omics technology.

Patient Similarity Network (PSN) Construction

- For each omics dataset, compute patient-patient similarity matrices using Pearson's correlation coefficient between patient profiles [30].

- Convert similarity matrices to individual PSNs where nodes represent patients and edge weights represent similarity measures.

- Apply WGCNA algorithm to normalize networks and enforce scale-freeness of degree distribution [30].

Network Fusion and Feature Extraction

- Fuse individual omics-specific PSNs using Similarity Network Fusion (SNF) algorithm to create an integrated patient network [30].

- Extract network features from the fused network including:

- Centrality measures (degree, closeness, betweenness, eigenvector centrality)

- Modularity features derived from spectral clustering or Stochastic Block Model

- Concatenate centrality and modularity features to create comprehensive feature vectors for each patient.

Predictive Modeling and Validation

- Train machine learning classifiers (Deep Neural Networks, SVM, Random Forests) using network features to predict clinical outcomes [30].

- Implement Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) to identify most predictive network features.

- Evaluate model performance using cross-validation and independent test sets where available.

- Compare network-level fusion against feature-level fusion approaches to demonstrate superior performance of integrated network construction [30].

Interaction Asymmetry vs. Traditional Network Metrics

The distinction between interaction asymmetry and traditional network metrics represents a fundamental advancement in network-based target prioritization. This comparison highlights critical methodological differences and their implications for drug target identification.

Table 3: Interaction Asymmetry vs. Traditional Network Metrics

| Analytical Aspect | Traditional Network Metrics | Interaction Asymmetry Approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Prioritizes nodes based on topological properties (degree, betweenness centrality) without considering directional influence [26]. | Accounts for directional regulatory relationships and context-specific interactions that may not correlate with connectivity [28] [29]. |

| Target Prioritization Basis | "Hub" nodes with highest connectivity are often prioritized as potential targets [26]. | Nodes with asymmetric influence (master regulators) are prioritized regardless of connectivity [28]. |

| Biological Relevance | May identify broadly important housekeeping genes rather than disease-specific drivers [26]. | Captures specialized regulatory functions with greater disease specificity [27] [29]. |

| Data Requirements | Relies primarily on static interaction networks (PPI, co-expression) [26]. | Incorporates directional data (gene regulatory networks, signaling pathways) and temporal dynamics [28]. |

| Validation Outcomes | In ALS study: Traditional metrics alone insufficient for predicting pathogenic genes [27]. | In ALS study: Integration of directional x-QTL data identified 105 high-confidence targets with enriched immune pathways [27]. |

| Implementation Examples | Simple degree-based prioritization in protein interaction networks [26]. | Network propagation that follows directional edges [27] [28]; multilayer networks with asymmetric layer connections [29]. |

Successful implementation of network-based multi-omics integration requires specific computational tools, databases, and analytical resources. The following table catalogs essential components for establishing this research capability.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Biological Network Databases | BioGRID [28], KEGG PATHWAY [28], STRING | Source of curated protein-protein interactions, metabolic pathways, and functional associations for network construction. |

| Multi-Omics Data Resources | GWAS Catalog, GTEx (for x-QTLs), TCGA, TARGET, SEQC | Provide disease-relevant omics datasets for integration, including genomic, transcriptomic, epigenomic, and proteomic data. |

| Network Analysis Tools | netOmics [28], multiXrank [29], Cytoscape | Specialized software for constructing, visualizing, and analyzing multi-omics networks; implements propagation algorithms. |

| Computational Frameworks | Similarity Network Fusion (SNF) [30], ARACNe [28], Deep Learning architectures | Algorithms for network fusion, regulatory network inference, and graph-based machine learning. |

Network-based multi-omics integration represents a paradigm shift in drug target identification, moving beyond the limitations of both reductionist single-omics approaches and traditional network analysis. The comparative analysis presented in this guide demonstrates that methods capturing interaction asymmetry—such as network propagation on directional networks and multilayer integration—consistently outperform approaches relying solely on traditional network metrics for identifying therapeutically relevant targets.

The evidence from neurodegenerative disease, oncology, and infectious disease applications confirms that context-aware, direction-sensitive network analysis produces more biologically meaningful target prioritization. Furthermore, the methodological frameworks and experimental protocols outlined provide researchers with practical roadmaps for implementing these powerful approaches in their own drug discovery pipelines.

As the field evolves, future developments in single-cell multi-omics, spatial mapping technologies, and artificial intelligence will further enhance the resolution and predictive power of network-based integration, potentially unlocking novel therapeutic opportunities for complex diseases that have previously eluded targeted intervention.

Graph Neural Networks and Knowledge Graphs for Asymmetric Drug-Drug Interactions

In pharmacotherapy, the concurrent use of multiple drugs—a practice known as polypharmacy—has become increasingly common, particularly for managing complex diseases and elderly patients with multiple comorbidities. While often therapeutically necessary, this practice introduces the significant risk of drug-drug interactions (DDIs), where the activity of one drug is altered by another. Traditionally, DDI prediction has often treated these interactions as symmetric relationships, assuming that if drug A affects drug B, the reverse interaction occurs identically. However, this assumption fails to capture interaction asymmetry, where the effect of drug A on drug B differs fundamentally from the effect of drug B on drug A. This asymmetry arises from complex biological mechanisms, such as when one drug inhibits the metabolic enzyme responsible for clearing another drug, without the reverse occurring.

The emerging research paradigm recognizes that traditional symmetric network metrics are insufficient for capturing these directional relationships. This guide examines how Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) and Knowledge Graphs (KGs) are advancing the prediction of asymmetric DDIs by incorporating directional information and relational context. By comparing cutting-edge computational frameworks, we provide researchers with objective performance evaluations and methodological insights to guide model selection for asymmetric DDI prediction.

Comparative Analysis of GNN and KG Models for Asymmetric DDI Prediction

The following table summarizes the core architectural approaches and quantitative performance of recent models designed for or applicable to asymmetric DDI prediction.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of GNN and KG Models for DDI Prediction

| Model Name | Core Architectural Approach | Key Innovation for Asymmetry | Reported Performance (Dataset) | Performance Highlights |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DRGATAN [32] | Directed Relation Graph Attention Aware Network | Encoder learning multi-relational role embeddings across different relation types; explicit modeling of directional edges. | Superior to recognized advanced methods (Specific dataset not named) | Superior performance vs. advanced baselines; handles relation types and directionality. |

| Dual-Pathway Fusion (Teacher) [33] | KG & EHR Fusion with Distillation | Conditions KG relation scoring on patient-level EHR context; produces interpretable, mechanism-specific alerts. | Maintains precision across multi-institution test data (Multi-institution EHR + DrugBank) | Higher precision at comparable F1; reduces false alerts; identifies clinically recognized mechanisms for KG-absent drugs. |

| MDG-DDI [34] | Multi-feature Drug Graph (Transformer + DGN + GCN) | Integrates semantic (from SMILES) and structural (molecular graph) features for robust representation. | Consistently outperforms SOTA in transductive & inductive settings (DrugBank, ZhangDDI, DS) | Strong gains predicting interactions involving unseen drugs (inductive learning). |

| GNN with Conditional Graph Information Bottleneck [5] | Graph Information Bottleneck Principle | Identifies minimal predictive molecular subgraph for a given drug pair; core substructure depends on interaction partner. | Enhanced predictive performance on common DDI datasets (Common DDI datasets) | Improves prediction and provides substructure-level interpretability. |

| GCN with Skip Connections [35] | Graph Convolutional Network with Skip Connections | Skip connections mitigate oversmoothing in deep GNNs, potentially preserving nuanced directional signals. | Competent accuracy vs. other baseline models (3 different DDI datasets) | Simple yet effective baseline; competent accuracy. |

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Breakdown

The DRGATAN Framework for Directed Relations