A Comprehensive Guide to Ecological Connectivity Analysis: From Foundational Concepts to Advanced Applications in Research and Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the current state, methods, and applications of ecological connectivity analysis.

A Comprehensive Guide to Ecological Connectivity Analysis: From Foundational Concepts to Advanced Applications in Research and Drug Discovery

Abstract

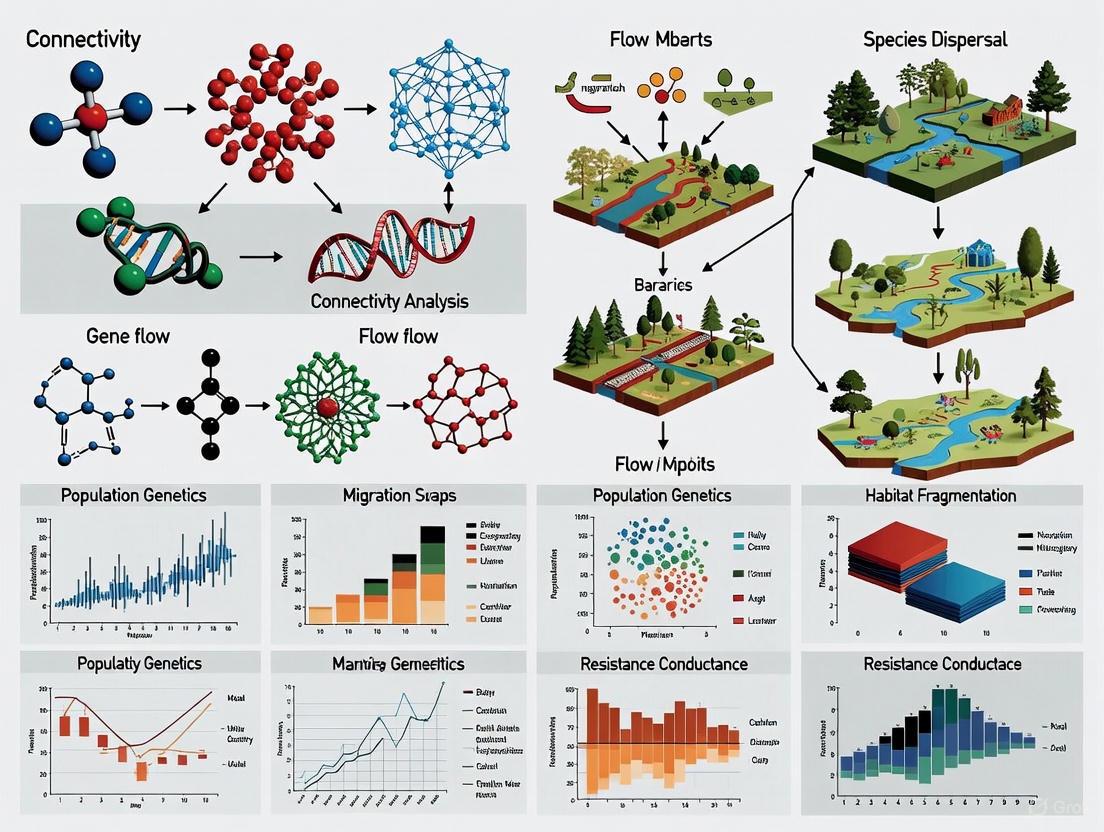

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the current state, methods, and applications of ecological connectivity analysis. It explores foundational principles, including key definitions of structural and functional connectivity, and reviews dominant computational approaches such as circuit theory, graph theory, and resistant kernels. The content delves into strategies for increasing biological realism in models, addresses common challenges in multispecies analysis, and offers guidance for method selection and troubleshooting. A comparative evaluation of model performance using simulation frameworks is presented, alongside emerging trends like the integration of network-based link prediction for biomedical applications such as drug-target and drug-drug interaction prediction. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this guide bridges ecological methodology with biomedical innovation.

The Foundations of Ecological Connectivity: Core Concepts, Definitions, and Scientific Importance

Ecological connectivity is a foundational concept in conservation science, defined as the degree to which the landscape facilitates or impedes the movement of organisms, gametes, and ecological processes between resource patches [1]. In an era of escalating human pressures on natural systems, understanding and quantifying connectivity has become critical for maintaining biodiversity, ecosystem functioning, and resilience [1] [2]. The concept extends beyond simple physical linkages to encompass the functional effectiveness of these connections for specific ecological processes and organisms [2].

The significance of ecological connectivity is increasingly recognized in global conservation policy frameworks. It serves as a key component in international agreements including the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, particularly its "30x30" target aiming to conserve 30% of Earth's land and oceans by 2030 [1]. As landscapes become increasingly fragmented by human activities, maintaining and restoring connectivity provides an essential strategy for enabling species adaptation to climate change and preventing further biodiversity loss [3].

Table 1: Core Dimensions of Ecological Connectivity

| Dimension | Definition | Primary Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Connectivity | Physical arrangement and spatial configuration of landscape elements | Habitat pattern, physical continuity, landscape composition [2] |

| Functional Connectivity | Effectiveness of connections for facilitating specific ecological processes | Species movement, gene flow, nutrient cycling, ecological interactions [2] |

| Spatial Connectivity | Connections across geographical space | Landscape linkages, corridors, stepping stones [2] [4] |

| Temporal Connectivity | Connections maintained across time | Seasonal migrations, climate-driven range shifts, long-term genetic exchange [3] |

Conceptual Framework: Structural and Functional Connectivity

Structural Connectivity

Structural connectivity refers to the physical arrangement and spatial configuration of habitat patches, corridors, and other landscape elements [2]. It focuses exclusively on the pattern of the landscape without explicit consideration of species-specific behavior or ecological processes. Key structural elements include habitat patches, corridors, stepping stones, and the surrounding matrix, all characterized by their composition, configuration, and physical relationships [2].

In forest ecosystems, structural connectivity is primarily driven by forest loss and gain dynamics [2]. Deforestation, often associated with agricultural expansion, typically decreases structural connectivity by increasing fragmentation, while forest regrowth and expansion can enhance it [2]. Structural connectivity provides the physical template upon which functional connectivity operates, but does not guarantee functional connectivity, as species may not utilize physically connected elements due to behavioral constraints or other factors [2].

Functional Connectivity

Functional connectivity emphasizes the quality and effectiveness of connections between landscape elements in facilitating specific ecological processes [2]. It considers how the structural arrangement of habitats actually influences the movement of organisms, genes, and ecological processes [2]. Unlike structural connectivity, functional connectivity is inherently species-specific and process-dependent, varying according to the ecological requirements and behavioral characteristics of the focal species or process [2].

The concept of functional diversity helps bridge the gap between structure and function by examining how the eco-morpho-physiological characteristics of species influence their response to environmental drivers and their role in ecosystem processes [2]. This approach provides critical understanding of the relationship between taxonomic diversity and ecosystem functioning, highlighting how functional connectivity supports biodiversity and enhances ecosystem resilience to environmental changes [2].

Quantitative Assessment Methods and Metrics

Landscape Connectivity Metrics

Advanced quantitative methods have been developed to measure and analyze ecological connectivity across different spatial and temporal scales. Graph theory has emerged as a powerful mathematical framework for representing landscapes as networks of nodes (habitat patches) and links (potential movement pathways) [1] [4]. This approach enables the calculation of various metrics that quantify different aspects of connectivity.

Table 2: Key Connectivity Metrics and Their Applications

| Metric | Calculation Method | Ecological Interpretation | Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Integral Index of Connectivity (IIC) | Based on habitat patch area and connectivity [1] | Measures overall landscape connectivity considering all possible paths | Protected area network assessment [1] |

| Probability of Connectivity (PC) | Incorporates dispersal probabilities between patches [1] | Estimates functional connectivity for species with specific dispersal capabilities | Conservation corridor planning [1] |

| Equivalent Connected Area (ECA) | Area of a single fully connected patch providing equivalent connectivity [1] | Standardized measure for comparing connectivity across landscapes | Monitoring connectivity changes over time [1] |

| Directional Connectivity Index (DCI) | Graph theory-based, multiscale metric [5] | Quantifies connectivity in specific directions; sensitive to environmental degradation | Early-warning indicator, restoration planning [5] |

| dECA | Change in ECA over time [1] | Measures gains or losses in connectivity | Evaluating management interventions [1] |

Hydrological Connectivity Applications

The concept of connectivity extends beyond terrestrial ecosystems to aquatic systems, where hydrological connectivity describes the water-mediated transfer of matter, energy, and organisms within or between elements of the hydrologic cycle [6]. This includes longitudinal connectivity (upstream-downstream along river networks), lateral connectivity (between rivers and floodplains), and vertical connectivity (surface water-groundwater exchanges) [6].

Measurement approaches for hydrological connectivity include field-based methods (e.g., dye tracing), indirect measurements (e.g., runoff analysis), remote sensing techniques (e.g., InSAR), and modeling approaches including process-based models, graph theory, and entropy-based metrics [6]. Recent advances incorporate AI-driven modeling and real-time monitoring to better capture the dynamic nature of hydrological connectivity [6].

Experimental Protocols for Connectivity Assessment

Fine-Scale Connectivity Modeling in Fragmented Landscapes

This protocol outlines a method for characterizing connectivity in fragmented agricultural landscapes, with particular emphasis on the role of fine-scale features such as scattered trees [4].

Methodology Details:

Identification of Key Ecological Parameters: The model is parameterized using values derived from systematic reviews of empirical studies [4]:

- Interpatch dispersal distance: 1000 m

- Gap-crossing distance threshold: 100 m

- Minimum habitat patch size: 10 ha

Spatial Data Pre-processing:

- Habitat map creation: Identify and map native woody vegetation patches meeting the minimum size threshold [4].

- Resistance surface development: Assign movement resistance values to different land cover types based on species-specific permeability [4].

- Gap-crossing layer generation: Identify areas where the distance between habitat elements exceeds the gap-crossing threshold [4].

Connectivity Analysis:

- Least-cost path analysis: Model potential movement pathways that minimize cumulative resistance between habitat patches [4].

- Graph-theoretic network analysis: Calculate connectivity metrics to quantify the importance of individual patches and links to overall landscape connectivity [4].

- Scenario comparison: Contrast connectivity patterns with and without fine-scale features such as scattered trees to assess their functional significance [4].

Protected Area Connectivity Assessment (ProtConn)

This protocol evaluates the connectivity of protected area networks using the ProtConn method implemented in the Makurhini R package [1].

Methodology Details:

Data Requirements:

- Protected areas spatial layer (e.g., World Database on Protected Areas)

- Land cover/land use map

- Species-specific dispersal distance data

Analysis Steps:

- Calculate landscape fragmentation statistics to characterize the structural configuration of habitat patches [1].

- Apply graph theory connectivity indices including the Integral Index of Connectivity (IIC) and Probability of Connectivity (PC) to assess functional connectivity [1].

- Compute ProtConn metrics that quantify the percentage of protected connected land, considering both the spatial distribution of protected areas and the connectivity through the broader landscape matrix [1].

- Identify connectivity priorities by evaluating the relative importance of different landscape elements for maintaining connectivity, using centrality indices and link removal analysis [1].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Connectivity Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Makurhini R Package | Calculates landscape fragmentation and connectivity indices [1] | Conservation planning, protected area network assessment [1] |

| Graph Theory Algorithms | Models landscape as networks of nodes and links [1] [4] | Identifying critical corridors and stepping stones [1] [4] |

| Least-Cost Path Analysis | Predicts movement routes based on landscape resistance [4] | corridor design, impact assessment [4] |

| Remote Sensing & GIS | Provides spatial data on habitat distribution and landscape structure [6] | Mapping structural connectivity, change detection [6] |

| GPS Telemetry & Animal Tracking | Collects movement data for model validation [3] | Measuring functional connectivity, parameterizing resistance surfaces [3] |

| Dispersal and Gap-Crossing Thresholds | Species-specific movement parameters [4] | Model parameterization, conservation planning [4] |

Conceptual Integration Framework

The relationship between structural patterns and functional processes in ecological connectivity can be visualized through an integrated conceptual framework that accounts for both landscape and social-ecological dimensions.

This framework illustrates how structural connectivity (landscape pattern) influences functional connectivity (movement and processes), which in turn determines biodiversity outcomes and ecosystem services [2]. These ecological outcomes affect human well-being, shaping the social-ecological context that includes human decisions, cultural values, and economic activities [2]. This social-ecological context drives management interventions and policy frameworks, which ultimately feedback to modify landscape structure through conservation actions [2]. The dashed lines represent direct human impacts on both landscape structure and ecological processes, highlighting the interconnected nature of social-ecological systems [2].

Emerging Perspectives and Future Directions

Contemporary connectivity science is expanding beyond traditional ecological boundaries to incorporate social-ecological dimensions that recognize the intricate connections between human well-being and ecosystem health [2]. The Nature's Contributions to People framework emphasizes the role of human societies, cultural beliefs, and practices in shaping relationships with nature, requiring connectivity assessments to consider both ecological and socio-cultural values [2].

Technological innovations are rapidly advancing connectivity analysis capabilities. AI-driven modeling approaches enhance pattern recognition and predictive accuracy, while real-time monitoring through sensor networks and remote sensing provides unprecedented temporal resolution of connectivity dynamics [6]. The integration of movement ecology with landscape genetics offers powerful new approaches for quantifying functional connectivity across different taxonomic groups and spatial scales [3].

Future connectivity research will increasingly focus on dynamic connectivity assessments that account for temporal variation in landscape permeability due to seasonal changes, disturbance events, and long-term climate shifts [6]. The development of standardized metrics and integrated assessment frameworks will facilitate comparison across studies and regions, supporting more effective conservation planning and policy implementation [6].

Ecological connectivity, defined as the unimpeded movement of species and the flow of genes that sustains healthy populations, is a foundational component for combating the biodiversity and climate change crises [7]. It represents the functional link between habitat patches, facilitating critical ecological processes at multiple scales. For researchers and practitioners, understanding and quantifying connectivity is not merely an academic exercise but a pressing need to inform effective conservation strategies, from the designation of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) to the restoration of fragmented forest landscapes [7] [8]. This document provides a detailed framework for analyzing ecological connectivity, presenting standardized protocols, data visualization techniques, and essential reagent solutions tailored for research aimed at preserving dispersal, gene flow, and ultimately, population persistence in a changing world.

Key Concepts and Quantitative Foundations

The theoretical importance of connectivity is realized through measurable genetic and demographic outcomes. The following concepts are central to its analysis, and the associated quantitative data provides the basis for empirical study.

- Genetic Diversity and Population Structure: Connectivity mitigates genetic erosion and inbreeding in isolated subpopulations. A lack of connectivity leads to increased genetic differentiation, quantifiable through metrics like FST (Fixation Index). For instance, the octocoral Eunicella verrucosa exhibits significant regional population structure (e.g., FST between southern Portugal and northwest Ireland), indicative of restricted gene flow [8].

- Gene Flow: This is the transfer of genetic material between populations, which can be contemporary or historical. Studies using microsatellite loci have shown that for many species, such as E. verrucosa, the vast majority of gene flow originates from sites within regions, with specific areas (e.g., southwest Britain) acting as important source populations [8].

- Population Persistence: Connectivity supports metapopulation dynamics, where a network of subpopulations can be maintained through migration and recolonization, thereby reducing extinction risk [8]. This is critical for species with small population sizes and low dispersal abilities, which are particularly vulnerable to habitat fragmentation [7].

Table 1: Quantitative Metrics for Assessing Connectivity from Genetic Data

| Metric | Description | Application Example | Typical Value Range (from search results) |

|---|---|---|---|

| FST (Fixation Index) | Measures population differentiation due to genetic structure. | Comparing regional populations of Eunicella verrucosa [8]. | >0 (0 = no differentiation, 1 = complete differentiation) |

| Number of Microsatellite Loci | Count of highly variable genetic markers used for population-level analysis. | Genotyping individuals of E. verrucosa and Alcyonium digitatum [8]. | 8-13 loci per species [8] |

| Contemporary Gene Flow Rate | Estimated rate of current migration between populations. | Identifying southwest Britain as a source population for exogenous genetic variants [8]. | Predominantly from sites within regions [8] |

| Effective Population Size (Ne) | The number of breeding individuals in an idealized population that would show the same genetic properties. | Inferred for Alcyonium digitatum to explain its lack of population structure [8]. | Can be large for species with high gene flow [8] |

Experimental Protocols for Connectivity Analysis

This section outlines a standardized protocol for assessing ecological connectivity through population genomics, using the study of temperate octocorals as a detailed model [8].

Protocol: Assessing Population Structure and Gene Flow Using Microsatellite Markers

1. Objective: To quantify genetic diversity, population structure, and patterns of historical and contemporary gene flow in a target species across its geographical range.

2. Materials: (Refer to Section 5: "The Scientist's Toolkit" for a detailed list of research reagents).

3. Methodology:

Step 1: Sample Collection

- Collect tissue samples from the target species across its known distribution range. A minimum of 20-30 individuals per sampling site is recommended to capture adequate genetic variation.

- Preserve samples immediately in >95% ethanol or using silica gel desiccant for DNA stabilization during transport and storage.

- Record precise GPS coordinates for all sampling locations.

Step 2: DNA Extraction and Quality Control

- Extract genomic DNA from approximately 20 mg of tissue using a commercial DNA extraction kit.

- Quantify DNA concentration and purity using a spectrophotometer (e.g., Nanodrop). Acceptable samples have an A260/280 ratio of ~1.8.

- Dilute DNA to a standardized working concentration (e.g., 10-20 ng/μL) for downstream applications.

Step 3: Microsatellite Genotyping

- Select a panel of species-specific microsatellite loci. The published study used 13 loci for E. verrucosa and 8 for A. digitatum [8].

- Amplify loci via Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) using fluorescently labelled primers.

- Separate PCR amplicons by capillary electrophoresis on a genetic analyzer.

- Score alleles using genotyping software against an internal size standard.

Step 4: Data Analysis

- Genetic Diversity: Calculate observed (HO) and expected (HE) heterozygosity, and allelic richness for each population using software like GENALEX or Arlequin.

- Population Structure: Calculate pairwise FST values between all sampling sites. Perform an Analysis of Molecular Variance (AMOVA) to partition genetic variation within and among populations. Visualize broad-scale structure with a Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA).

- Gene Flow: Use Bayesian clustering algorithms (e.g., implemented in STRUCTURE or BAPS) to infer the number of genetic clusters (K) and assign individuals to populations. Estimate contemporary migration rates using programs like BAYESASS.

4. Data Interpretation:

- Low FST and no clear clusters (as in A. digitatum) suggest high connectivity and gene flow [8].

- Significant FST and distinct clusters (as in E. verrucosa) indicate restricted gene flow and fragmented population structure, highlighting areas where connectivity is low [8].

- Identification of source populations from gene flow analysis provides critical information for prioritizing areas for conservation, such as the design of MPA networks [8].

Visualizing Connectivity Concepts and Data

The following diagrams, generated using Graphviz and adhering to the specified color and style guidelines, illustrate core concepts and workflows in connectivity analysis.

Diagram: Population Connectivity and Gene Flow

Diagram: Genetic Analysis Experimental Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Connectivity Genetics Research

| Item | Function | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Tissue Collection Kit | Standardized collection and preservation of biological samples for DNA stability. | Includes 2mL cryovials, 95-100% ethanol, forceps, scissors, and silica gel. |

| Commercial DNA Extraction Kit | High-throughput, consistent purification of high-quality genomic DNA. | DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen) or equivalent. |

| Microsatellite Primer Panels | Species-specific primers for amplifying highly variable genetic loci. | Must be developed or sourced from literature for the target organism (e.g., 13 loci for E. verrucosa) [8]. |

| PCR Master Mix | Pre-mixed solution containing Taq polymerase, dNTPs, and buffer for efficient DNA amplification. | Includes fluorescently labelled primers for fragment analysis. |

| Genetic Analyzer & Internal Size Standard | Capillary electrophoresis system for precise fragment sizing. | Applied Biosystems instruments with GS600-LIZ size standard. |

| Population Genetics Software | Suite of programs for calculating diversity indices, F-statistics, and modeling gene flow. | GENALEX, Arlequin, STRUCTURE, BAYESASS. |

Resistance Surfaces, Least-Cost Paths, and Metapopulation Capacity

Application Notes

Conceptual Foundations and Definitions

Resistance Surfaces, Least-Cost Paths (LCPs), and Metapopulation Capacity represent three foundational concepts in ecological connectivity analysis. Resistance surfaces are spatial grids where each cell value represents the hypothesized cost of movement for an organism through that landscape element, reflecting factors like energetic costs, behavioral aversion, or mortality risk [9] [10]. These surfaces serve as the fundamental input for connectivity models, translating landscape features into biologically relevant movement costs [11].

Least-cost path analysis identifies optimal routes between locations that minimize the cumulative cost of movement, derived by applying graph theory algorithms like Dijkstra's Algorithm to resistance surfaces [9]. This approach assumes organisms select paths that optimize movement efficiency across landscapes with varying permeability [12].

Metapopulation capacity, introduced by Hanski, provides a quantitative measure of a landscape's potential to support a viable metapopulation [13]. Calculated as the leading eigenvalue of a landscape matrix that incorporates patch areas and connectivities, it represents a threshold value above which a species is predicted to persist in a fragmented landscape [13]. This measure enables researchers to rank landscapes by their capacity to support viable populations and predict population persistence under different fragmentation scenarios.

Comparative Performance in Connectivity Modeling

Table 1: Comparative performance of connectivity modeling approaches across different ecological contexts

| Model Type | Key Strengths | Key Limitations | Ideal Application Contexts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Least-Cost Paths | Simple to implement and interpret; requires limited input data; accessible to practitioners [12] | Assumes perfect landscape knowledge and single optimal path; may oversimplify movement ecology [14] | Directed movement toward known destinations; conservation corridor planning [14] |

| Resistant Kernels | Does not require destination knowledge; incorporates dispersal thresholds; models connectivity from sources [14] | Requires dispersal threshold parameterization; computational intensity varies by implementation | Multi-directional dispersal; population expansion scenarios; habitat prioritization [14] |

| Circuit Theory | Considers all possible movement paths; analogizes to electrical current flow; good for probability estimation [14] [15] | Can be computationally intensive; may overestimate diffuse movements for some species [14] | Population genetics studies; uncertainty in movement pathways; multiple path evaluation [15] |

| Metapopulation Capacity | Rigorously derived from population theory; provides persistence threshold; integrates patch quality and connectivity [13] | Requires patch-based landscape representation; less spatially explicit for corridor identification | Landscape prioritization; patch network evaluation; population viability assessment [13] |

Recent comparative evaluations using simulated movement data have revealed significant performance differences among connectivity modeling approaches. Resistant kernels and Circuitscape generally outperform factorial least-cost paths in predicting simulated movement pathways across most scenarios [14]. However, LCP analysis remains valuable when movement is strongly directed toward known locations or when data and computational resources are limited [14].

Validation Evidence from Empirical Studies

Table 2: Empirical validation evidence for connectivity modeling approaches

| Study System | Model Approach | Validation Method | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Urban hedgehogs (Erinaceus europaeus) [12] [16] | Least-cost path analysis | Translocation experiment with repeated measures; movement trajectory analysis | Hedgehogs followed LCP orientation in connecting contexts; moved faster and straighter in un-connecting contexts; validated LCP predictions |

| African wild dogs (Lycaon pictus) [12] | Least-cost path analysis | GPS location overlap with predicted corridors | Majority of GPS locations overlapped with predicted LCP corridors, supporting model predictions |

| Multiple simulated species [14] | Factorial LCPs, Resistant Kernels, Circuitscape | Pathwalker individual-based movement simulations | Resistant kernels and Circuitscape performed most accurately in nearly all cases; LCPs performed well only with strongly directed movement |

| Endangered butterfly networks [13] | Metapopulation capacity | Population persistence in fragmented landscapes | Metapopulation capacity successfully predicted persistence thresholds and ranked landscape networks by viability potential |

Experimental validation using translocation studies has demonstrated that least-cost path analysis can effectively identify landscape contexts that facilitate movement. In urban environments, hedgehogs showed movement patterns consistent with LCP predictions, moving along corridor orientations in highly connecting contexts while exhibiting faster, more direct movement when traversing resistant matrices [12] [16]. This validation approach provides important evidence for the ecological relevance of resistance-based connectivity models.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Resistance Surface Parameterization and Optimization

Purpose: To construct and optimize resistance surfaces that accurately reflect species-specific movement costs across landscapes.

Materials and Reagents:

- GIS software with raster processing capabilities (e.g., ArcGIS, QGIS, R with terra package)

- Landscape variable layers (land cover, topography, human footprint, vegetation density)

- Species occurrence, movement, or genetic data

- Resistance surface optimization tools (e.g., ResistanceGA, MEMGENE)

Procedure:

Landscape Data Preparation [11]

- Collect relevant environmental variables representing hypothesized movement barriers and facilitators

- Reproject all layers to common coordinate system, extent, and resolution

- Consider thematic resolution (number of habitat classes) and its biological relevance

Initial Resistance Value Assignment [10] [11]

- Assign preliminary resistance values based on:

- Expert opinion surveys (structured interviews with species experts)

- Literature review of similar species and landscapes

- Empirical data when available (telemetry, genetic, or occurrence data)

- Consider nonlinear relationships between habitat suitability and resistance

- Assign preliminary resistance values based on:

Resistance Surface Construction [9] [11]

- Apply map algebra to combine multiple resistance layers:

cost = 1 + Σ(landscape_feature × weight) - Ensure uniform value of 1 in absence of landscape features to maintain Euclidean distance properties

- Apply map algebra to combine multiple resistance layers:

Model Optimization [11]

- Compare alternative resistance surfaces using:

- Genetic algorithms for unconstrained optimization

- Maximum likelihood population effects modeling

- Fitting to empirical movement or genetic data

- Select optimal surface based on:

- Akaike Information Criterion or similar model selection metrics

- Statistical fit between predicted and observed connectivity

- Compare alternative resistance surfaces using:

Sensitivity Analysis [17]

- Test sensitivity of results to cost value variations

- Evaluate both least-cost path locations and cost distance values

- Assess influence of landscape composition and configuration

Protocol 2: Experimental Validation of Predicted Corridors

Purpose: To empirically test the functionality of predicted connectivity corridors using translocation experiments.

Materials and Reagents:

- GPS or radio-telemetry equipment

- Data loggers for movement tracking

- GIS software for spatial analysis

- Statistical software (R, Python)

- Predicted least-cost paths and resistance surfaces

Procedure:

-

- Implement repeated-measures translocation design

- Select paired study sites: predicted high-connectivity vs. low-connectivity contexts

- Standardize for temporal variables (season, time of day, weather conditions)

- Counterbalance treatment order to control for learning effects

Animal Handling and Translocation [12]

- Capture individuals from stable home ranges

- Fit with appropriate tracking technology (GPS collars, radio transmitters)

- Transport to release sites using standardized protocols

- Release at predetermined points in both connectivity contexts

Movement Data Collection [12] [16]

- Track individuals for sufficient duration to capture exploratory movement

- Record high-frequency location data (appropriate to species mobility)

- Document movement parameters: trajectory, speed, tortuosity, stop locations

- Note behavioral observations where possible

Movement Pattern Analysis [12]

- Eulerian Approach: Compare spatial overlap between observed movement trajectories and predicted corridors

- Lagrangian Approach: Analyze movement characteristics (speed, step length, tortuosity) between connectivity contexts

- Test specific hypotheses:

- Path orientation relative to predicted LCPs (Rayleigh's test)

- Movement speed differences between contexts (linear mixed models)

- Habitat selection along movement paths (resource selection functions)

Model Validation Assessment [12]

- Quantify correspondence between predicted and observed movement patterns

- Evaluate model performance using appropriate metrics (correlation, spatial overlap)

- Refine resistance surfaces based on validation results

Protocol 3: Metapopulation Capacity Assessment

Purpose: To quantify the capacity of a fragmented landscape to support viable metapopulations.

Materials and Reagents:

- GIS software for patch delineation

- Landscape matrix processing tools

- Population viability analysis software

- Species-specific demographic parameters

- Habitat patch maps with quality assessments

Procedure:

Patch Network Delineation [13]

- Identify and map all habitat patches in the landscape

- Calculate patch areas using GIS tools

- Assess habitat quality for each patch (field surveys or remote sensing)

Connectivity Assessment [13]

- Measure inter-patch distances using effective distances (least-cost distances)

- Calculate connectivity metrics for each patch incorporating:

- Distance to other patches

- Areas of other patches

- Species-specific dispersal kernel

Landscape Matrix Construction [13]

- Construct landscape matrix M where elements mᵢⱼ represent the contribution of patch j to patch i

- Matrix elements are functions of:

- Patch areas Aᵢ and Aⱼ

- Inter-patch distance dᵢⱼ

- Species-specific dispersal parameter α

- Standard form: mᵢⱼ = exp(-αdᵢⱼ) × AᵢAⱼ for i ≠ j

Metapopulation Capacity Calculation [13]

- Compute the leading eigenvalue (λₘ) of the landscape matrix M

- This eigenvalue represents the metapopulation capacity of the landscape

- Compare λₘ to species-specific persistence threshold

Scenario Analysis [13]

- Evaluate how metapopulation capacity changes with:

- Habitat loss (patch removal)

- Habitat gain (patch addition or restoration)

- Altered connectivity (barrier creation or mitigation)

- Rank alternative conservation scenarios by their impact on λₘ

- Evaluate how metapopulation capacity changes with:

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential research reagents and computational tools for connectivity analysis

| Tool/Reagent | Primary Function | Application Context | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| GIS Software (ArcGIS, QGIS, R terra/sf) [11] | Spatial data processing and analysis | Data preparation, resistance surface construction, visualization | Coordinate transformation, raster algebra, spatial statistics |

| Least-Cost Path Algorithms (Dijkstra's) [9] | Optimal path identification | Corridor modeling, connectivity mapping | Graph theory implementation, cumulative cost minimization |

| Circuit Theory Tools (Circuitscape) [14] [15] | Current flow modeling | Movement probability estimation, landscape genetics | Analogizes movement to electrical current, considers all possible paths |

| Resistant Kernels [14] | Dispersal threshold modeling | Population spread, multi-directional connectivity | Models connectivity from sources without requiring destinations |

| Conefor [18] | Landscape connectivity metrics | Patch-based connectivity, network analysis | Calculates probability of connectivity, integral index of connectivity |

| Pathwalker [14] | Individual-based movement simulation | Model validation, movement process testing | Simulates biased random walks, incorporates energy, attraction, risk |

| ResistanceGA [11] | Resistance surface optimization | Parameter estimation, model selection | Genetic algorithm approach, multiple resistance surface types |

| Telemetry Technology (GPS, radio tags) [12] | Animal movement tracking | Empirical data collection, model validation | High-frequency location data, variable sampling intervals |

| MEMGENE [11] | Spatial genetic analysis | Landscape genetics, resistance surface validation | Spatial autocorrelation analysis, genetic pattern detection |

Integrated Analytical Framework

The most robust connectivity analyses integrate multiple approaches to leverage their complementary strengths. For example, resistance surfaces constructed through optimization procedures can feed into both least-cost path analyses for corridor identification and metapopulation capacity calculations for population viability assessment [13] [11]. This integrated approach allows researchers to address connectivity at multiple organizational levels, from individual movement paths to population persistence.

Future methodological developments should focus on incorporating dynamic connectivity modeling that accounts for temporal environmental variation, improving uncertainty quantification in connectivity predictions, and developing more efficient computational methods for handling large spatial datasets [15] [11]. The integration of connectivity models with hierarchical population models represents a particularly promising avenue for simultaneously estimating species distribution, movement, and landscape resistance from empirical data [15].

Ecological connectivity, defined as the degree to which a landscape facilitates or impedes animal movement, represents a critical frontier in conservation science amidst widespread biodiversity loss [19]. While functional connectivity is fundamentally specific to species and their movement processes, the logistical and financial constraints of collecting sufficient data for all species of interest have traditionally limited conservation planning [19]. Single-species models, though valuable for understanding specific ecological relationships, fail to capture the complex interactions and cumulative landscape effects on biological communities. The multispecies challenge thus represents a paradigm shift from species-specific conservation to ecosystem-level planning that acknowledges the integrated nature of ecological systems. This approach is increasingly vital for supporting animal movement and gene flow across fragmented landscapes, particularly as governments worldwide establish policies targeting wildlife corridors of national importance [19]. By moving beyond single-species models, researchers and conservation practitioners can develop more efficient and effective strategies for maintaining biodiversity at landscape scales.

Quantitative Foundations: Evaluating Multispecies Connectivity Model Performance

National-Scale Model Validation

A comprehensive national-scale study conducted across Canada provides critical quantitative evidence for assessing multispecies connectivity model performance. Researchers evaluated two generalized multispecies (GM) connectivity models—park-to-park and omnidirectional approaches—against movement data from 3,525 GPS-collared individuals representing 17 species (16 mammals and 1 avian species) across 46 study areas [19]. The models were developed using circuit theory applied to a resistance-to-movement surface created from expert ranking of 16 natural and anthropogenic land cover variables [19]. The validation assessed model prediction accuracy against multiple movement processes measured at different scales, from within home range to presumed dispersal.

Table 1: Performance of Generalized Multispecies Connectivity Models Across Species and Movement Types

| Model Performance Category | Accuracy Range | Key Findings | Notable Species Patterns |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Prediction Accuracy | 52% to 78% of datasets and movement processes [19] | Areas important for movement were accurately predicted for majority of cases | Better for species averse to human disturbance (72-78% accuracy) [19] |

| Movement Process Performance | Lower for fast movements [19] | Omnidirectional model slightly better for multiple movement processes | Less accurate for species tolerant of human disturbance, steep slopes, and/or high elevations (38-41% accuracy) [19] |

| Model Type Comparison | Omnidirectional superior for multiple movement processes [19] | Both models useful for time-sensitive, landscape-scale projects | Species-specific models still required for some land management decisions [19] |

Multispecies Migratory Connectivity Assessment

For migratory species, a hemispheric-scale study developed a specialized multispecies connectivity parameter to assess population risk from global change. This research integrated movement data from >329,000 migratory birds of 112 species to quantify multispecies migratory connectivity—the linking of individuals between regions in different seasons [20]. When combined with projected climate and land-cover changes (hazard) and species conservation assessment scores (vulnerability), this exposure metric helped estimate relative risk of population declines across the Western Hemisphere [20]. The analysis revealed that multispecies migratory connectivity constituted the strongest driver of risk relative to hazard and vulnerability, underscoring the importance of synthesizing connectivity across species for comprehensive risk assessment [20].

Table 2: Multispecies Connectivity Applications Across Ecological Contexts

| Application Context | Spatial Scale | Methodological Approach | Key Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Terrestrial Landscape Connectivity | National (Canada) [19] | Circuit theory with expert-derived resistance surface | Identified corridors of national importance; informed federal conservation policy [19] |

| Migratory Bird Connectivity | Hemispheric (Western Hemisphere) [20] | Integration of tracking data with environmental change projections | Revealed highest risk for connections between Canadian breeding and South American non-breeding regions [20] |

| Regional Ecological Networks | Regional (Calabria, Italy) [21] | Landscape graph theory with multi-temporal assessment | Defined habitat patches, linkages, and corridors for 66 focal faunal species [21] |

Experimental Protocols for Multispecies Connectivity Modeling

Protocol 1: Developing Generalized Multispecies Connectivity Models

Purpose: To create generalized multispecies (GM) connectivity models that predict areas important for animal movement across multiple species without requiring individual species movement data.

Materials and Reagents:

- Land Cover Data: 16 different natural and anthropogenic land cover variables (e.g., built environments, major highways, steep slopes, waterbodies, natural habitats) [19]

- Resistance Surface: Expert-derived ranking of landscape resistance to movement [19]

- Protected Areas Database: Spatial data on parks and Other Effective Area-Based Conservation Measures (OECMs) [19]

- Computational Tool: Circuitscape software for circuit theory applications [19]

Procedure:

- Resistance Surface Development:

- Assemble 16 land cover variables representing natural and anthropogenic features

- Assign resistance values through expert ranking: high resistance to human-dominated land cover and natural barriers; medium resistance to permeable human-modified areas; low resistance to natural, unmodified land cover [19]

Source and Destination Definition:

Circuit Theory Application:

- Implement circuit theory using Circuitscape software

- Treat the gridded landscape representation as a conductive layer with resistors between neighboring grid cells

- Model current flow patterns from source to ground locations [19]

Current Density Calculation:

- Generate gridded surface of current density values representing probability of animal movement

- Interpret higher current density values as areas with higher movement probability [19]

Model Validation:

- Collect GPS location data from multiple individuals across multiple species

- Test model predictions against observed movement processes at different scales (within home range to dispersal)

- Calculate prediction accuracy as percentage of datasets where models correctly identified important movement areas [19]

Protocol 2: Assessing Multispecies Migratory Connectivity and Risk

Purpose: To evaluate multispecies migratory connectivity and assess relative risk of population declines from global change factors across the Western Hemisphere.

Materials and Reagents:

- Movement Data: Tracking data from >329,000 migratory birds [20]

- Species Data: 112 migratory bird species [20]

- Environmental Data: Projected climate and land-cover changes to 2050 [20]

- Conservation Assessment: Species conservation assessment scores (e.g., Partners in Flight ACAD) [20]

Procedure:

- Multispecies Migratory Connectivity Quantification:

- Compile and integrate movement data from 112 migratory bird species

- Define connections between breeding and non-breeding regions for each species

- Develop multispecies migratory connectivity parameter representing exposure to global change [20]

Hazard Assessment:

- Obtain projected climate change data (temperature changes by mid-century)

- Acquire land-cover vulnerability to change by 2050 spatial data

- Combine climate and land-cover projections to quantify habitat hazard [20]

Vulnerability Assessment:

- Compile species conservation assessment scores from existing databases

- Use standardized metrics of species vulnerability to environmental changes [20]

Risk Integration:

- Combine exposure (multispecies migratory connectivity), hazard, and vulnerability metrics

- Calculate relative risk of migratory bird population declines across 921 hemispheric connections [20]

Spatial Prioritization:

- Identify connections categorized as very high risk

- Determine geographic patterns of risk concentration (e.g., breeding regions in eastern United States, connections between Canada and South America) [20]

Visualization Framework for Multispecies Connectivity Analysis

Workflow for Multispecies Connectivity Modeling and Validation

Comparative Model Architecture: Park-to-Park vs. Omnidirectional Approaches

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Multispecies Connectivity Analysis

| Research Tool | Application Context | Specific Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Circuitscape Software [19] | Landscape connectivity modeling | Applies circuit theory to model movement probability | National-scale connectivity models in Canada [19] |

| GPS Telemetry Data [19] [20] | Model validation | Provides empirical movement data for testing predictions | 3,525 individuals across 17 species in Canada [19]; >329,000 birds in hemispheric study [20] |

| Expert-Derived Resistance Surface [19] | Landscape resistance quantification | Translates land cover features into movement costs | 16 land cover variables ranked by resistance value [19] |

| Landscape Graph Theory [21] | Ecological network analysis | Models structural connectivity and network robustness | Multispecies ecological networks in Calabria, Italy [21] |

| Morphological Spatial Pattern Analysis (MSPA) [21] | Habitat pattern quantification | Identifies and classifies habitat patches and corridors | Multi-temporal assessment of habitat quality [21] |

The integration of multispecies approaches represents a transformative advancement in ecological connectivity analysis, moving beyond the limitations of single-species models to provide comprehensive conservation solutions. The robust validation of generalized multispecies connectivity models demonstrates their utility for predicting areas important for animal movement across diverse species and movement processes [19]. While species-specific models remain necessary for certain land management decisions, GM models offer efficient, cost-effective tools for landscape-scale conservation planning, particularly for time-sensitive projects and policy development. The successful application of these approaches across terrestrial, migratory, and regional contexts highlights their versatility and underscores their growing importance in addressing the interconnected challenges of biodiversity conservation, habitat fragmentation, and climate change. As ecological research continues to confront the multispecies challenge, these methodologies provide a critical foundation for sustaining ecological networks and maintaining functional connectivity across increasingly modified landscapes.

Ecological connectivity—the unimpeded movement of species and the flow of ecological processes—has emerged as a critical frontier in conservation science. In the context of rapid climate change, this connectivity facilitates essential species shifts in distribution and supports the genetic exchange necessary for population resilience [22]. The integrity of ecological networks directly influences the capacity of biodiversity to adapt to changing conditions, making its analysis a central pillar of effective conservation strategies. This document provides detailed application notes and standardized protocols for researchers quantifying and applying connectivity analysis to meet climate adaptation and biodiversity goals, framed within a broader thesis on ecological connectivity analysis methods.

Core Concepts and Multi-Scale Framework

Typology of Ecological Connectivity

Ecological connectivity manifests in three primary forms, each requiring distinct measurement approaches and offering different insights for conservation [23]:

- Structural Connectivity: Pertains to the physical configuration of habitats and landscape features, such as the presence of corridors linking habitat patches. It is a spatial measure of landscape permeability.

- Functional Connectivity: Describes the behavioral response of organisms to the landscape structure, reflecting the actual movement of individuals, genes, or propagules (e.g., seeds, larvae) between resource patches.

- Genetic Connectivity: The level of gene flow between sub-populations, which is fundamental for maintaining genetic diversity and population viability over time.

The relationship between these types is often hierarchical and interdependent, as visualized below.

A Cross-Scale Framework for Climate Adaptation

Climate adaptation strategies for biodiversity are most effective when implemented across a nested, multi-scale framework [22]. This framework highlights the vertical interactions and interdependencies between strategies operating at regional, landscape, and site levels, ensuring that local actions contribute to broader conservation goals.

- Regional Scale (Macro): Involves dynamic conservation planning informed by climate vulnerability assessments and species distribution modeling. The focus is on identifying climate refugia and prioritizing regions for large-scale conservation investment.

- Landscape Scale (Meso): Focuses on protected area networks, the corridors that connect them, and the overall matrix permeability. This scale is critical for facilitating species range shifts in response to climate change.

- Site Scale (Micro): Emphasizes in-situ and ex-situ conservation actions for keystone species, habitat restoration, and real-time monitoring of invasive species.

The following diagram illustrates this cross-scale interaction.

Quantitative Methods for Measuring Connectivity

A range of quantitative methods is available for measuring different facets of ecological connectivity. The choice of method depends on the research question, target species, spatial scale, and available resources.

Table 1: Methods for Measuring Ecological Connectivity

| Method | Description | Primary Connectivity Type Measured | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Analysis | Uses neutral or adaptive genetic markers to assess population structure and infer gene flow. | Genetic | Provides historical, integrated measure of gene flow; applicable to elusive species. | Can be expensive and time-consuming; may not reveal contemporary barriers. |

| Individual Tracking | Employs electronic devices (GPS, PIT tags, acoustic telemetry) to monitor animal movement. | Functional | Provides highly detailed data on individual movement paths and behavior. | Limited by device range, battery life, cost; data may not be generalizable. |

| Biophysical Modeling | Uses numerical models to simulate the dispersal of organisms (e.g., plant seeds, coral larvae) based on physical processes. | Functional / Structural | Can predict connectivity patterns over large scales and for future scenarios; cost-effective. | Requires extensive parameterization and validation; model uncertainty. |

| Landscape Circuitry | Applies circuit theory or least-cost path analysis to resistance surfaces to model movement probability. | Structural / Functional | Effective for modeling connectivity across heterogeneous landscapes for multiple species. | Relies on accurate parameterization of landscape resistance. |

Experimental Protocols for Connectivity Analysis

Protocol 4.1: Landscape Connectivity Analysis Using Circuit Theory

This protocol provides a standardized methodology for modeling functional landscape connectivity for terrestrial or marine species using circuit theory, implemented in tools such as Circuitscape.

1. Research Question and Hypothesis Formulation

- Objective: To identify key corridors and pinch points for species movement within a fragmented landscape under current and projected climate conditions.

- Hypothesis: Specific landscape features (e.g., rivers, roads, forest cover) will significantly influence movement permeability, and climate-driven habitat shifts will alter corridor importance.

2. Data Acquisition and Pre-processing

- Habitat Suitability Model (HSM): Develop a species distribution model using occurrence data and environmental variables (e.g., bioclimatic, land cover, topography) [24]. Tools like

EcoNicheScan streamline this process. - Landscape Resistance Surface: Transform the HSM into a resistance surface where resistance values are inversely related to habitat suitability. Expert opinion or empirical data can guide this transformation.

3. Model Parameterization and Execution

- Software: Use the

Circuitscapemodule, accessible through theEcoNicheSplatform or as a standalone tool [24]. - Focal Nodes: Define source and destination locations for the circuit model (e.g., protected areas, known breeding sites).

- Model Run: Execute the model to calculate current flow across the landscape, which predicts movement probability.

4. Validation and Analysis

- Ground-Truthing: Validate model predictions using independent data from tracking studies, camera traps, or genetic analysis [23].

- Pinch Point Identification: Analyze current flow maps to identify areas of concentrated flow, which represent critical corridors vulnerable to disruption.

- Climate Projection: Repeat the analysis using HSMs projected under future climate scenarios to assess corridor stability.

The workflow for this protocol is summarized below.

Protocol 4.2: Assessing Population Genetic Connectivity

This protocol outlines the steps for using molecular markers to quantify genetic connectivity, providing a historical measure of gene flow among populations.

1. Sample Collection and DNA Extraction

- Sampling Design: Collect tissue samples non-invasively (e.g., hair, feces) or invasively (blood, fin clips) from individuals across the target populations. A minimum of 20-30 individuals per location is recommended.

- Preservation: Preserve samples appropriately (e.g., ethanol, silica gel, freezing).

- DNA Extraction: Use commercial kits or standard phenol-chloroform methods to extract high-quality genomic DNA.

2. Genotyping and Sequencing

- Marker Selection: Choose appropriate molecular markers (e.g., microsatellites, Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms - SNPs) based on research budget and questions.

- Platform: Utilize platforms like Fragment Analysis for microsatellites or Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) for SNP discovery and genotyping.

3. Data Analysis

- Genetic Diversity: Calculate within-population diversity indices (e.g., expected heterozygosity, allelic richness).

- Population Structure: Analyze genetic structure using F-statistics (F~ST~), Analysis of Molecular Variance (AMOVA), and Bayesian clustering methods (e.g., STRUCTURE).

- Gene Flow Estimation: Use assignment tests or coalescent-based models (e.g., in MIGRATE-N, BAYESASS) to estimate contemporary and historical migration rates.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Implementing the protocols above requires a suite of analytical tools and data resources. The following table details key "research reagents" for the field of ecological connectivity analysis.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Connectivity Analysis

| Tool / Solution | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

EcoNicheS R Package |

Software Package | Provides an integrated Shiny dashboard for ecological niche modeling, niche overlap analysis, and connectivity modeling [24]. | Streamlines the workflow from species distribution modeling to connectivity analysis; ideal for researchers seeking an all-in-one, reproducible solution. |

| Circuitscape | Software Module | Models landscape connectivity using circuit theory, identifying corridors and pinch points. | A core analytical tool for Protocol 4.1; often integrated within platforms like EcoNicheS. |

| GPS / Satellite Telemetry Units | Hardware | Tracks the fine-scale and large-scale movements of individual animals. | Provides empirical data for validating functional connectivity models (Protocol 4.1) and studying movement behavior. |

| Microsatellite or SNP Panels | Molecular Reagent | A set of optimized genetic markers for genotyping individuals of a specific species. | The core reagent for Protocol 4.2 (Genetic Connectivity); used to generate the raw data for population genetic analysis. |

| Bioclimatic Variable Datasets (e.g., WorldClim, CHELSA) | Data | Provides standardized, global layers of temperature and precipitation-derived variables. | Essential for building climate-informed Habitat Suitability Models in connectivity and niche modeling [24]. |

Application Notes for Conservation and Policy

The ultimate value of connectivity analysis lies in its application to real-world conservation challenges. The following notes guide the translation of research findings into actionable strategies.

Note 1: Prioritizing Corridors for Conservation - Connectivity models should be used to identify and rank corridors based on their current usage, projected stability under climate change, and the number of species they benefit. This enables efficient allocation of limited conservation resources to the most critical linkages [22].

Note 2: Designing Climate-Resilient Protected Area Networks - Conservation planning must move beyond static protected areas. Connectivity analysis allows for the design of dynamic networks that incorporate stepping-stone habitats and climate refugia, facilitating species' range shifts in response to climate change [22].

Note 3: Mitigating Infrastructure Impacts - Environmental impact assessments for new infrastructure (e.g., roads, pipelines) must integrate connectivity models to forecast fragmentation effects. The results should directly inform the placement and design of mitigation structures like wildlife overpasses or underpasses.

Note 4: Informing Assisted Migration Decisions - For species unable to track shifting climates naturally, genetic connectivity analysis can identify source populations with adaptive alleles. This information is critical for planning genetically informed assisted migration or managed translocations.

Note 5: Monitoring and Adaptive Management - Establishing a connectivity corridor is not a one-time action. A robust monitoring program—using techniques from the protocols above—is essential to track its effectiveness and guide adaptive management in response to ecological changes.

A Practical Toolkit: Dominant Connectivity Models and Their Advanced Applications

Landscape resistance represents a quantitative estimate of the movement cost imposed by landscape features, serving as the foundational spatial layer for modeling ecological connectivity. It integrates species-specific behavioral and physiological responses to landscape structure, enabling predictions of individual movement, gene flow, and functional connectivity between habitat patches. The precision of resistance surfaces directly determines the reliability of connectivity models in conservation planning, with recent methodological advances improving their empirical derivation and optimization. This application note outlines standardized protocols for constructing, parameterizing, and applying resistance surfaces, with particular emphasis on emerging computational tools and cross-disciplinary applications, including the study of drug resistance evolution.

Landscape resistance quantifies the degree to which landscape features impede or facilitate movement for a particular organism [11]. Unlike simple structural connectivity, resistance surfaces model functional connectivity – the species-specific perception and utilization of landscape elements during movement processes. These spatial representations are crucial for predicting how animals navigate fragmented habitats, how genes flow between populations, and how diseases or adaptive traits spread across environments.

The theoretical foundation of landscape resistance rests on circuit theory and least-cost path modeling, where landscapes are represented as conductive surfaces with varying permeability to biological flows. Resistance values assigned to different land cover types reflect biological costs based on energy expenditure, predation risk, or behavioral preference. When properly parameterized, resistance surfaces can accurately predict genetic differentiation [25], disease transmission patterns, and evolutionary trajectories – including the development of treatment-resistant pathogens [26] [27].

Analytical Framework and Data Requirements

Workflow for Resistance Surface Development

The development and application of resistance surfaces follows a systematic workflow encompassing data preparation, surface construction, and analytical implementation. The following diagram illustrates this structured process:

Data Types for Resistance Surface Parameterization

Resistance surfaces can be parameterized using diverse data sources, each with distinct strengths and applications. The selection of appropriate data type depends on research questions, target species, and available resources.

Table 1: Data Types for Parameterizing Resistance Surfaces

| Data Type | Primary Applications | Key Considerations | Example Analytical Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expert Opinion | Preliminary models, data-poor species, conservation planning | Subject to bias; should be combined with empirical data when possible [25] | Expert surveys, analytical hierarchy process |

| Species Detection | Presence-absence modeling, habitat suitability | May confound habitat use with movement [25] | Species distribution models, occupancy modeling |

| Telemetry/Relocation | Movement ecology, resource selection | Reflects within-home range behavior; may not represent dispersal [11] | Step selection functions, path-level analysis |

| Genetic Data | Landscape genetics, population connectivity | Reflects successful reproduction post-dispersal [11] | Isolation-by-resistance, causal modeling |

| Pathway Data | Direct movement quantification, corridor identification | Logistically challenging to collect [25] | Least-cost path analysis, randomized shortest paths |

Protocols for Resistance Surface Construction

Protocol 1: One-Stage Expert Opinion Approach

Purpose: To rapidly develop preliminary resistance surfaces when empirical data are limited.

Materials:

- GIS software (e.g., ArcGIS, QGIS)

- Environmental spatial layers (land cover, topography, human footprint)

- Expert survey instruments

Procedure:

- Variable Selection: Identify landscape variables hypothesized to influence species movement.

- Expert Elicitation: Survey multiple subject matter experts to assign resistance values (1-100) to each landscape variable category.

- Value Aggregation: Calculate mean or median resistance values for each variable category across experts.

- Surface Combination: Combine individual resistance layers using weighted geometric mean or fuzzy logic.

- Sensitivity Analysis: Test how variation in expert-assigned values affects model outcomes.

Validation: Compare model predictions with any available occurrence data or movement observations.

Protocol 2: Two-Stage Empirical Optimization

Purpose: To develop empirically-validated resistance surfaces using genetic or movement data.

Materials:

- R statistical environment with ResistanceGA package [28]

- Genetic distance matrix or movement data

- Raster layers of candidate environmental variables

Procedure:

- Genetic Data Preparation: Calculate pairwise genetic distances between individuals or populations using appropriate metrics (e.g., Fst, Dps, or relatedness).

- Environmental Distance Calculation: For each candidate surface, compute effective distances between sample locations using CIRCUITSCAPE or similar tools.

- Optimization: Use ResistanceGA to iteratively optimize resistance values using genetic algorithms:

- Model Selection: Compare optimized surfaces using AICc or similar information criteria.

- Surface Refinement: Select best-performing model and validate with independent data.

Validation: Use k-fold cross-validation or independent movement tracks to assess predictive accuracy.

Protocol 3: Integrating Habitat Suitability

Purpose: To derive resistance surfaces from habitat suitability models.

Materials:

- Species occurrence data

- Environmental predictor variables

- R packages (maxent, ResourceSelection, amt)

Procedure:

- Habitat Model Development: Build habitat suitability model using appropriate algorithm (e.g., MaxEnt, resource selection functions).

- Suitability Transformation: Convert suitability values to resistance using negative exponential or linear transformations:

- Negative exponential: Resistance = a + b × exp(c × suitability)

- Linear: Resistance = a - b × suitability

- Transformation Optimization: Test multiple transformation functions and select based on correlation with genetic or movement data.

- Surface Application: Use transformed surface in connectivity models.

Note: Simple linear inversion of suitability values is generally not recommended, as organisms may traverse sub-optimal habitats during movement [11].

Advanced Applications: Drug Resistance Evolution

The principles of landscape resistance find powerful application in evolutionary biology, particularly in modeling the fitness landscapes of drug-resistant pathogens. In this context, "resistance" refers to reduced drug susceptibility, while "landscape" represents the fitness topography across genotypic space.

Evolutionary Pathways to Drug Resistance

The development of antimalarial resistance in Plasmodium falciparum demonstrates how adaptive landscapes dictate evolutionary trajectories. Mutations in the dhfr gene (C59R, I164L, N51I, S108N) create a genotypic landscape where epistatic interactions determine accessibility of evolutionary paths [27]:

Protocol 4: Quantifying Global Epistasis in Fitness Landscapes

Purpose: To analyze how drug environment modulates epistatic interactions in resistance evolution.

Materials:

- Growth rate data for pathogen genotypes across drug concentration gradient

- Computational environment for regression analysis (R, Python)

- Genotypic data for focal mutations

Procedure:

- Fitness Measurement: Culture isogenic strains with different mutation combinations across a drug concentration gradient (e.g., 10⁻² μM to 10³ μM pyrimethamine).

- Background Fitness Calculation: For each focal mutation, calculate fitness of all genetic backgrounds lacking that mutation: f(B).

- Mutation Effect Quantification: Compute fitness effect of adding focal mutation: Δf = f(B + i) - f(B).

- Global Epistasis Analysis: Perform linear regression between Δf and f(B) for each drug concentration:

- Δf = β₀ + β₁ × f(B) + ε

- Epistasis Modulation Assessment: Compare regression slopes (β₁) across drug concentrations to quantify environmental modulation of global epistasis.

- Effective Interaction Mapping: Calculate specific gene-by-gene and gene-by-environment interactions underlying global patterns.

Applications: This approach revealed that mutation C59R exhibits diminishing returns epistasis at low drug doses but increasing returns at high doses in malaria parasites [27].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Tools for Landscape Resistance Research

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Analysis Platforms | ArcGIS, QGIS, GRASS GIS | Data preparation, visualization, and basic analysis | Universal spatial data handling |

| R Packages for Connectivity | ResistanceGA, gdistance, amt, adehabitatLT | Resistance surface optimization and movement analysis | Empirical resistance estimation [11] [28] |

| Circuit Theory Applications | CIRCUITSCAPE, UNICOR | Modeling landscape connectivity and movement probability | Predicting gene flow and functional connectivity |

| Genetic Analysis Tools | SPAGeDi, CDPOP, STRUCTURE | Quantifying genetic structure and distances | Landscape genetics parameterization [28] |

| Environmental Data Sources | WorldClim, MODIS, NLCD, Copernicus | Providing environmental predictor variables | Initial resistance surface development |

Landscape resistance provides the fundamental spatial representation through which ecological connectivity is quantified and understood. The protocols outlined herein enable researchers to move beyond hypothetical connectivity models to empirically-grounded predictions of movement, gene flow, and evolutionary adaptation. The cross-pollination of concepts between landscape ecology and evolutionary biology – particularly in understanding drug resistance development – highlights the unifying power of resistance surfaces in predicting complex biological processes across diverse systems. Future methodological developments should focus on incorporating temporal dynamics, quantifying uncertainty, and improving computational efficiency for large-scale applications.

Ecological connectivity is a cornerstone of conservation science, critical for understanding and facilitating the movement of genes, individuals, and species in response to habitat fragmentation and climate change [29]. Computational models that map connectivity are indispensable for converting this concept into actionable conservation strategies. Among the numerous approaches developed, three algorithm families have become foundational in spatial ecology: Circuit Theory (operationalized in tools like Circuitscape), Graph Theory, and Resistant Kernels [30]. Each offers a distinct perspective on modeling landscape permeability and identifying crucial corridors for biodiversity conservation. This article provides application notes and experimental protocols for these core methodologies, framing them within a comparative context to guide researchers and scientists in selecting and implementing the most appropriate model for their specific ecological questions and systems.

The following table summarizes the core characteristics, strengths, and weaknesses of the three primary connectivity algorithm families.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Core Connectivity Algorithm Families

| Feature | Circuit Theory (Circuitscape) | Graph Theory | Resistant Kernels |

|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Basis | Electrical circuit theory (physics); random walk theory [31] | Mathematics of network structure; topology [32] | Cost-distance analysis; kernel density estimation [33] |

| Concept of Connectivity | Current flow; probability of movement across all possible pathways [31] | Linkage between habitat patches (nodes) via corridors (edges) [34] | Expected dispersal density from a source point given landscape resistance [29] |

| Primary Inputs | Resistance surface, core habitat patches (sources/destinations) [35] | Resistance surface, habitat patches (nodes) [32] | Resistance surface, source locations, dispersal threshold [30] |

| Key Outputs | Current density maps (cumulative current flow) [31] | Network graphs; metrics like Probability of Connectivity (PC), Integral Index of Connectivity (IIC) [32] | Dispersal probability surfaces from source points [33] |

| Advantages | Models diffuse, non-directed movement; accounts for multiple pathways; efficient for large landscapes [31] | Intuitive network representation; rich set of metrics for patch prioritization; low data requirements [32] | Does not require destination points; continuous connectivity surface; predicts occupancy potential [30] |

| Disadvantages | Less intuitive for directed movement; can be computationally intensive for very large grids [35] | Simplifies landscape to patches and links; may oversimplify continuous resistance [34] | Scale-dependent (sensitive to dispersal threshold); requires definition of source strength [29] |

Application Notes and Protocols

Protocol: Modeling Connectivity with Circuit Theory (Circuitscape)

Circuit theory, implemented in software like Circuitscape, models landscape connectivity by analogizing it as an electrical circuit [31]. Habitat patches are represented as nodes, the landscape matrix as a resistor network, and moving organisms as electrical current. This approach is powerful for predicting movement probabilities across all possible pathways.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Circuit Theory Applications

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Description | Example Source/Format |

|---|---|---|

| Resistance Surface | A raster grid where pixel values represent the cost of movement for an organism. | Geospatial layer (e.g., GeoTIFF) derived from land cover, human impact, or topography [35] |

| Core Area Map | A raster or vector layer identifying habitat patches that serve as source and destination nodes. | Derived from species distribution models, expert opinion, or telemetry data [35] |

| Circuitscape Software | The computational engine that solves the circuit and generates current flow maps. | Standalone application or Julia package [35] |

Experimental Workflow:

- Construct Resistance Surface: Parameterize a raster layer where cell values represent movement cost. This can be based on species-specific Resource Selection Functions (RSFs) [35], expert opinion, or generic models of human modification [29]. Ensure the resistance surface is scaled appropriately for the study organism.

- Define Core Habitats: Identify and delineate source and destination habitat patches. These cores can be defined using a decision threshold on a habitat suitability model (e.g., a sensitivity of 0.95 for correct prediction of use) [35] or through other ecological criteria.

- Configure Circuitscape:

- Input the resistance and core area rasters.

- Select the pairwise mode to calculate connectivity between all core area pairs.

- Set the connection scheme to connect eight neighbors to allow for diagonal movement [35].

- Execute Model and Validate: Run Circuitscape to generate a cumulative current density map. Validate the model predictions where possible, for instance, by using a subset of telemetry data not used in model parameterization. One study achieved 78% accuracy in predicting wolverine habitat use with a similar approach [35].

- Interpret Results: The output current map highlights pixels with high current flow, which represent predicted corridors or pinch-points. Higher current density indicates a higher probability of being used by moving organisms [31].

Protocol: Modeling Connectivity with Graph Theory

Graph theory simplifies a landscape into a habitat network where patches are nodes and potential dispersal pathways are edges [34]. This abstraction is highly effective for assessing the topological importance of individual patches and the overall robustness of a habitat network.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Graph Theory Applications

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Description | Example Source/Format |

|---|---|---|

| Habitat Patches (Nodes) | Vector polygons or raster cells representing suitable habitat. | Remote sensing classification, land cover maps, or habitat models [32] |

| Distance Matrix | A table containing effective distances (least-cost path distances) or Euclidean distances between all node pairs. | Calculated from a resistance surface using GIS software [34] |

| Graph Analysis Software | Tools to construct the graph and calculate metrics. | Packages in R (igraph), Python (NetworkX), or standalone tools (Conefor) |

Experimental Workflow:

- Delineate Habitat Patches: Identify and map all habitat patches in the landscape. These can be forest fragments, wetlands, or other relevant ecosystems, often derived from land cover classifications [32].

- Define Network Connections (Edges): Establish links between patches. This typically involves calculating the least-cost path distance between patches using a resistance surface. A dispersal threshold is applied, where only patches within a certain cost-distance are considered connected [34].

- Calculate Graph Metrics: Compute key metrics to evaluate connectivity. The most consistently used and credible indices are [32]:

- Probability of Connectivity (PC): Measures the probability that two individuals placed randomly in the landscape fall into habitat patches that are interconnected.